Impact of Birth Order on Paediatric Allergic Diseases: A National Birth Cohort in Japan

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Summary

- The relationship between birth order and each allergic disease varied with disease and age.

- The protective effect of birth order suggested involvement of mechanisms other than the hygiene hypothesis.

The presence of siblings has previously been reported to have a protective effect on allergic diseases, but the effect remains to be elucidated [1]. Our group conducted a longitudinal study of neonates born in 2001 from all over Japan and evaluated the relationships between birth order and each of bronchial asthma, food allergy and atopic dermatitis [2]. Since then, the prevalence of childhood allergy in Japan has increased, whereas bronchial asthma and atopic dermatitis have started to decline [3]. The environment surrounding allergic diseases has also changed, including an increase in the rate of daycare attendance [4]. In this study, we surveyed neonates born in 2010 to examine whether our findings were temporally robust.

We performed a nationwide cohort study using data from the 21st Century Longitudinal Newborn Survey conducted by Japan's Ministry of Health, targeting all babies born in Japan between 10 May 2010 and 24 May 2010 [5]. Baseline questionnaires for the survey were sent to 43,767 households, of which 38,554 responded (response proportion, 88%). Follow-up questionnaires were sent to the respondents annually thereafter. The outcomes were defined as any outpatient visit for these allergic diseases in each period between 6 months and 9 years of age. Log-binomial linear regression analysis was performed, using first-born children as a reference, and adjusted relative risks (aRR) were calculated after controlling for potential confounders. Subgroup analysis was also conducted to examine effect modification by early daycare attendance, based on whether or not the child was attending daycare at the age of 1.5 years. Further analysis was also conducted with an interaction term between birth order and early daycare attendance.

Additional information about study methods and findings are available in the following repository: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14318912.

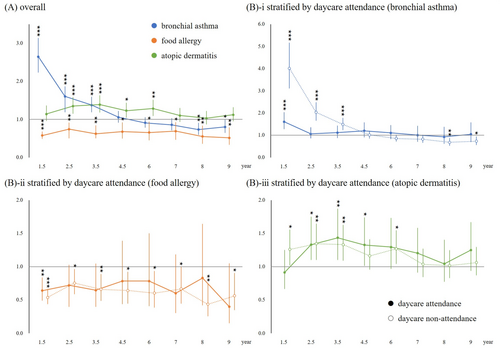

Higher birth order was associated with an increased risk of bronchial asthma hospital visits in childhood, but a decreased risk during school age (Figure 1A). Compared with first-born children, aRR was 2.65 (95% CI 2.23–3.13) at the age of 6–18 months, and 0.73 (95% CI 0.60–0.90) at the age of 7–8 years for third- or later-born children. The risk of food allergy decreased consistently with higher birth order throughout the investigation period. Compared with the first-born children, aRR at the age of 6–18 months was 0.76 (95% CI 0.69–0.84) in the second-born children, and 0.58 (95% CI 0.49–0.68) in the third- or later-born children. On the other hand, the presence of older siblings increased the risk of atopic dermatitis, particularly in infancy. Compared with the first-born children, aRR 30–42 months after birth was 1.39 (95% CI 1.19–1.63) for the third- or later-born children. These results by disease were similar when stratified by sex.

Daycare attendance changed the impact of birth order on bronchial asthma (Figure 1B). In nonattendees, changes in RR for each allergic disease were broadly similar to those in the entire cohort. On the other hand, among attendees, the risk of bronchial asthma in infancy was particularly increased in the first child, reducing the noticeable differences associated with birth order. The risk of food allergy in infancy and atopic dermatitis during the study period was increased, and there were no apparent associations by birth order.

Despite significant changes in demographic characteristics and a time difference of 9 years, the results were consistent between the two cohorts [2]. We consider that the increased risk of asthma in infancy is due to asthma being a heterogeneous disease with distinct phenotypes induced by various causes [6]. The finding of a protective effect of birth order in school-age children is consistent with the hygiene hypothesis. However, the interaction between birth order and early daycare attendance increased the risk for school-age children; hence, factors, such as timing and intensity of exposure, may be involved [7]. Regarding food allergy, the protective effect of birth order was observed from early in life, but not in those attending daycare. This result could not be explained by the hygiene hypothesis and instead supports the prenatal origin hypothesis [1]. However, early weaning initiation, which may serve as a mediator between higher birth order and the development of allergies, was not considered in this study. Regarding atopic dermatitis, both the presence of siblings and daycare attendance were identified as risk factors in this study. These findings may reflect the complex pathology of atopic dermatitis, where allergic inflammation and impaired skin barrier function play interconnected roles [8].

Despite the large, representative sample size and high response proportion, this study had several limitations. First, the cohort was restricted to children born in May. Second, nearly 40% of the cohort were lost to follow-up. Third, the study was conducted in Japan, which limits its generalisability. Fourth, the study relied on parental reports, which may not accurately reflect clinical diagnoses. Fifth, while potential confounders were controlled for, residual confounding factors, such as parental allergic history, pet ownership or visitation behaviours, may have influenced the results.

The relationship between birth order and each allergic disease varied with the disease and age. Further research, including on the timing and intensity of exposure, is needed to explore these mechanisms and identify preventive measures for paediatric allergic diseases.

Author Contributions

M.K., M.I. and T.Y. conceptualised and designed this study. N.M. and T.Y. were involved in data collection and analysis. M.K., N.M. and M.I. interpreted the data. M.K. and M.I. were involved in manuscript writing and revision. H.T. supervised the data interpretation. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Okayama University Hospital, Ethics Committee (No. 1506-073).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in impact of birth order on pediatric allergic diseases at https://zenodo.org/, reference number http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14318912.