Outcomes of patients with light chain (AL) amyloidosis after failure of daratumumab-based therapy

Summary

As daratumumab use in AL amyloidosis increases, more patients will either relapse after or become refractory to daratumumab. We present the outcome of 33 patients with AL who failed on daratumumab (due to haematological relapse in 21 [64%] patients and inadequate haematological response in 12 [36%]) and received further treatment. Overall response rate in the post-daratumumab failure treatment was 55% (CR/VGPR: 14 [42%] and PR: 3 [9%] patients). Patients retreated with daratumumab and patients harbouring +1q21 had lower rates of response. Treatment of patients with AL who fail daratumumab therapy is feasible when non-cross-resistant drugs or other targeted therapies are available.

INTRODUCTION

Daratumumab is an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody which has shown efficacy in patients with newly diagnosed1 and relapsed/refractory light chain (AL) amyloidosis.2, 3 However, with the increasing use of daratumumab, there is a growing number of patients who either relapse or are or become refractory to daratumumab-based therapy. Given the lack of approved therapies for relapsed/refractory AL, the limited number of clinical trials in the setting of relapsed/refractory disease and the unique characteristics of these patients with multiorgan dysfunction, their management is challenging and data scarce. In the current analysis, we aim to describe the outcomes of 33 patients with AL amyloidosis who failed on daratumumab treatment and received further salvage therapy.

RESULTS

Patients' characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the patients at the time of initial diagnosis are shown in Table S1. Nine patients had SLiM CRAB criteria [9/9 had iFLC/uFLC (involved/uninvolved free light chain) ratio >100 and 2/9 had bone marrow plasma cell (BMPC) infiltration >60%]. In Table S2, we display patients' characteristics before initiation of treatment after daratumumab failure.

During daratumumab index therapy, 14 (42%) patients received daratumumab as initial therapy and 19 (58%) as salvage therapy. On the intention to treat (ITT) analysis, the haematological response rate at index daratumumab therapy was 61.3%, with CR/VGPR (comlete response/very good partial response) in 12 (36%) and PR (partial response) in 9 (27%) patients.

Daratumumab failure (DARA failure) was due to haematological relapse in 21 (64%) patients, inadequate haematological response in 10 (30%) and in 2 (6%) patients due to organ progression. The median time to ‘failure’ during or after therapy with daratumumab was 6.9 months (0.7–49.2). At the time of DARA failure, 8 (26%) patients had had organ response and 5 (16%) had organ progression. After DARA failure, 28 (85%) patients were exposed to bortezomib, 17 (51.5%) to lenalidomide and 4 (12%) to melphalan. Treatments post-DARA failure included re-treatment with daratumumab combinations in 9 (27%) patients, bortezomib-based regimens in 6 (18%), BCL2-inhibitors in 4 (12%), belantamab mafodotin in 4 (12%), pomalidomide in 4 (12%), lenalidomide-based regimens in 3 (9%), alkylator agents in 2 (6%) and ixazomib in 1 (3%) patient (Table S3). For patients that were retreated with daratumumab, the median time interval was 0.5 months (range 0–10.8); five patients were daratumumab refractory and four had achieved at least PR in daratumumab-based index therapy.

Haematological and organ responses

On ITT analysis, overall haematological response rate (ORR) in the post-DARA-failure treatment line was 55%, with CR/VGPR in 14 (42%) patients and PR in 3 (9%). Among the nine patients who retreated with daratumumab-based regimens, 2 (22%) patients achieved VGPR; for non-daratumumab regimens, haematological response rate was 68.1%, with CR/VGPR in 12 (50%) patients and PR in 3 (12.5%). ORR was 64.3% for patients that had received daratumumab as primary therapy versus 47.4% for salvage therapy (p = 0.647); CR/VGPR rate was 50% versus 36.8% (p = 0.497), respectively. Response rates were similar for those with and without prior exposure to bortezomib (57.1% vs. 40%, p = 0.529) and to lenalidomide (58.8% vs. 50.1, p = 0.595). ORR was 54.2% for patients who did not meet SLiM CRAB criteria versus 55.6% (p = 0.055) and CR/VGPR rate was 50% versus 22.2% (p = 0.241). Among patients harbouring amplification of 1q21 there was a trend for lower rates of haematological responses with only one patient achieving VGPR and two patients achieving PR (3/8, 37.5%) versus eight VGPR and one PR (9/15, 60%) among those without amp1q21 (p = 0.086). Patients who harboured translocation t(11;14) had similar outcomes compared to those without translocation (2 PR and 6 VGPR vs. 6 VGPR, p = 0.422) (Table 1). Among those with t(11;14) that received venetoclax, VGPR was observed in 3/3. Organ responses were observed in 8 (24%) patients (6 cardiac and 3 renal responses) and organ progression in 17 (51.5%), including 11 cardiac and 8 renal progressions, while 4 patients initiated dialysis.

| N | ORR | p-Value | VGPR + CR | CR | VGPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 33 | 17/33 (55%) | 14/33 (42%) | 1/33 (3%) | 13/33 (39%) | |

| Bortezomib-exposed | 28 | 16/28 (57.1%) | 13/28 (46.4%) | 1/28 (3.6%) | 12/28 (42.8%) | |

| Bortezomib-naïve | 5 | 2/5 (40%) | 0.529 | 1/5 (20%) | 0 | 1/5 (20%) |

| Lenalidomide-exposed | 17 | 10/17 (58.8%) | 7/17 (41.2%) | 1/17 (5.9%) | 6/17 (35.3%) | |

| Lenalidomide-naive | 16 | 8/16 (50.1%) | 0.595 | 7/16 (43.8%) | 0 | 7/16 (43.8%) |

| Hematological relapse | 21 | 12/21 (57.2%) | 9/21 (42.9%) | 0 | 9/21 (42.9%) | |

| Other reasons to initiate therapy | 12 | 6/12 (50%) | 0.856 | 5/12 (41.6%) | 1/12 (8.3%) | 4/12 (33.3%) |

| κFLC | 9 | 6/9 (66.7%) | 5/9 (55.6%) | 0 | 5/9 (56.6%) | |

| λFLC | 24 | 10/24 (50%) | 0.633 | 9/24 (37.5%) | 1/24 (4.2%) | 8/24 (33.3) |

| amp1q21 (+) | 8 | 3/8 (37.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 0 | 1/8 (12.5%) | |

| amp1q21 (−) | 15 | 9/15 (60%) | 0.086 | 8/15 (53%) | 0 | 8/15 (53%) |

| t(11;14) (+) | 10 | 7/10 (70%) | 6/10 (60%) | 0 | 6/10 (60%) | |

| t(11;14) (−) | 16 | 8/16 (50%) | 0.422 | 6/16 (37.5%) | 0 | 6/16 (37.5%) |

- Abbreviation: ORR: overall response rate, CR: complete response, VGPR: very good partiaal response, FLC: free light chain.

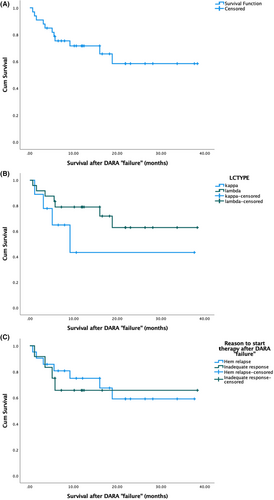

Survival

The median follow-up time since the initiation of therapy after daratumumab failure was 16.5 months. Eleven (33%) patients have died. One- and 2-year survival rates from the start of post daratumumab therapy was 69% and 57%. Patients with kappa light chain amyloidosis had numerically worse outcomes but did not reach statistical significance (median overall survival [OS] 9 months vs. not reached, p = 0.198) (Figure 1B). Although it seems that patients that started therapy after DARA ‘failure’ due to inadequate haematologic response had inferior survival than those that started therapy due to haematological relapse, there was no statistically significant difference in the median OS (p = 0.725) (Figure 1C). In univariate analysis, factors that were associated with inferior survival after daratumumab ‘failure’ were NTproBNP (N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide) (p = 0.002), ALP (alkaline phosphatase) (p < 0.001), iFLC (p = 0.005) and dFLC (difference of involved and uninvolved free light chain) (p = 0.025) (measured at the time of initiation of therapy post-DARA ‘failure’).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few studies that has focused specifically, on patients with AL amyloidosis that required further salvage therapy after they received daratumumab, which is a real and pressing clinical problem and, nowadays, a common clinical scenario.

In the current study, the overall haematological response rate in daratumumab exposed/refractory patients was 55% and deep haematological responses (at least VGPR) were observed in 42%. Although these results are not impressive, they are not substantially inferior compared to results from other studies that assess the outcome of relapsed/refractory AL. Studies that evaluated IMiDs (immunomodulatory imide drugs) as a salvage option demonstrate a haematological response rate of 40%–62%.4, 5 However, it has to be emphasized that most of these studies did not include patients refractory to daratumumab. On the other hand, studies with venetoclax in patients with translocation t(11;14), included daratumumab-exposed patients, demonstrate haematological response in 81% and CR/VGPR in 78%.6

The organ response rate of 24% is low and this might be attributed to the fact that this population consists of heavily pretreated patients with a prolonged disease course; organ dysfunction may be irreversible. In fact, some patients were already in organ progression when they failed treatment with daratumumab. Even in the study with venetoclax organ response rate was not higher than 38%.6 Also, this rate of organ responses aligns with a VGPR rate of <50%.

Twelve patients (36%) started treatment because of inadequate haematological response or the deterioration of organ function even without evidence of haematological relapse. This is unique in AL, when compared to myeloma therapeutics, but has been a rather common practice.7, 8 Unfortunately, there are no clear criteria for initiation of salvage therapy in AL amyloidosis and the definition of inadequate response may be broad. In our center ‘inadequate response’ is defined as a haematological response less than VGPR or a VGPR but with organ progression which is most probably related to the residual toxic light chains. It is notable that in our cohort, patients that received further therapy due to ‘inadequate’ response had inferior survival compared to patients that started therapy due to haematological disease progression. What's more, patients with kappa light chain AL had higher rates of response and deeper responses than patients with lambda light chain AL. Thus, treatment failure may be associated with different underlying biology.

As it was anticipated the level of NTproBNP remained a negative prognostic factor also for this population. Other factors that also had an impact on survival were the level of FLCs and the level of ALP. Our study population is small and these results should be interpreted with caution, but in the setting of relapsed/refractory AL, patients' characteristics are quite different than the time of initial diagnosis, with those having more advanced disease often not having the chance to receive salvage therapy. Cytogenetics did not have an impact on survival, but our cohort is small. In addition, our patients had previously received therapy with daratumumab and the characteristics of the clone may not be consistent with those at the time of diagnosis.

A rationale strategy to manage treatment failure is to use agents that the patients are not exposed to. Findings from our study also support this, as patients that were retreated with daratumumab had lower rates of response. The ever-evolving therapeutic landscape in the field of myeloma offers novel options. In subjects with translocation t(11;14) venetoclax yields quite impressive haematological responses.6 Conjugated antibodies, such as belantamab mafodotin, bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) and chimeric antigen T cells (CAR-T cells) are all targeting anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) in the surface of clonal plasma cells.9-12 Belantamab mafodotin is currently under investigation in relapsed/refractory AL amyloidosis in a clinical trial by European Myeloma Network (EMN) and the results are anticipated (NCT04617925). Besides BCMA, G-protein-coupled receptor family C group 5 member D (GPRC5D) and Fc receptor homolog 5 (FcRH5) are highly expressed in clonal plasma cells and BiTEs targeting these epitopes have yielded promising results in myeloma.13, 14 However, the introduction of these therapies in AL amyloidosis may be more difficult since patients may already suffer from neuropathy or hypotension, two common side effects of BiTEs. Recently, the first report for the safety and efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy in four patients with relapse/refractory AL amyloidosis was published, with encouraging results.15

In conclusion, treatment of patients with AL amyloidosis who have failed therapy with daratumumab is feasible, based on the use of non-cross-resistant drugs or other targeted therapies. Haematological responses in 55% and 2-year survival of 55% in this difficult to treat population are respectful and set the benchmark for the evaluation of new therapies in this setting.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Foteini Theodorakakou and Efstathios Kastritis performed data analysis and research design and wrote the paper. Despina Fotiou, Vasiliki Spiliopoulou, Maria Roussou, Panagiotis Malandrakis, Ioannis Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, Maria Gavriatopoulou, Nikolaos Kanellias, Magdalini Migkou and Evangelos Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou were involved in data collection and patient management and reviewed the manuscript. Evangelos Terpos and Meletios A. Dimopoulos reviewed the manuscript. Asimina Papanikolaou reviewed the majority of the pathology specimens and reviewed the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

EK: Consultancy—Janssen, Pfizer, Amgen—and Honoraria—Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, Genesis Pharma, Amgen; MG; Honoraria—Janssen, Genesis Pharma, Amgen, Karyopharm, Sanofi, GSK, Takeda; MG: Honoraria—Janssen, Genesis Pharma, Amgen, Karyopahrm, Sanofi, GSK, Taakeda; ET: Consultancy—Janssen, Amgen, Genesis Pharma, Celgene, Takeda, Sanofi—and Honoraria—Novartis, Janssen, Takeda, Genesis Pharma, Amgen, Celgene, Sanofi, BMS, GSK; MAD: Honoraria—Takeda, BMS, Amgen, Beigene, Janssen. DF, FT, MM, NK, PM, IN-S, EE-P, AP, VS, MR declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All subjects in the study were enrolled in IRB-approved protocols at the respective institutions and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.