Cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the Delta and Omicron waves in 348 691 UK users of the UK ZOE COVID Study app*

A.V. and B.M. contributed equally.

V.B. and M.F. jointly supervised this work.

Plain language summary available online

Summary

Background

Symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection have differed during the different waves of the pandemic but little is known about how cutaneous manifestations have changed.

Objectives

To investigate the diagnostic value, frequency and duration of cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and to explore their variations between the Delta and Omicron waves of the pandemic.

Methods

In this retrospective study, we used self-reported data from 348 691 UK users of the ZOE COVID Study app, matched 1 : 1 for age, sex, vaccination status and self-reported eczema diagnosis between the Delta and Omicron waves, to assess the diagnostic value, frequency and duration of five cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection (acral, burning, erythematopapular and urticarial rash, and unusual hair loss), and how these changed between waves. We also investigated whether vaccination had any effect on symptom frequency.

Results

We show a significant association between any cutaneous manifestations and a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result, with a diagnostic value higher in the Delta compared with the Omicron wave (odds ratio 2·29, 95% confidence interval 2·22–2·36, P < 0·001; and odds ratio 1·29, 95% confidence interval 1·26–1·33, P < 0·001, respectively). Cutaneous manifestations were also more common with Delta vs. Omicron (17·6% vs. 11·4%, respectively) and had a longer duration. During both waves, cutaneous symptoms clustered with other frequent symptoms and rarely (in < 2% of the users) as first or only clinical sign of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Finally, we observed that vaccinated and unvaccinated users showed similar odds of presenting with a cutaneous manifestation, apart from burning rash, where the odds were lower in vaccinated users.

Conclusions

Cutaneous manifestations are predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and their frequency and duration have changed with different variants. Therefore, we advocate for their inclusion in the list of clinically relevant COVID-19 symptoms and suggest that their monitoring could help identify new variants.

- Several studies during the wildtype COVID-19 wave reported that patients presented with common skin-related symptoms.

- It has been observed that COVID-19 symptoms differ among variants.

- No study has focused on how skin-related symptoms have changed across different variants.

- We showed, in a community-based retrospective study including over 348 000 individuals, that the presence of cutaneous symptoms is predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the Delta and Omicron waves and that this diagnostic value, along with symptom frequency and duration, differs between variants.

- We showed that infected vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals reported similar skin-related symptoms during the Delta and Omicron waves, with only burning rashes being less common after vaccination.

Skin-related symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported in the wildtype wave in 2020 and were notable both for their variety, spanning more than 30 different cutaneous manifestations,1, 2 and for their utility as a presenting symptom of COVID-19 that could lead to testing and diagnosis.3 Research from our group3 evaluating the prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in the UK between May and June 2020 found that 9% of users with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reported a skin rash. Moreover, using an independent retrospective survey, we showed that, for 21% of participants, the rash was the first symptom to appear, and in 17% it was the only sign of the infection.3

To date, the World Health Organization has identified five variants of concern that have been globally dominant.4 The Alpha variant (B.1.1.7) became dominant in September 2020, followed by the Beta variant (B.1.351) in May 2020 and the Gamma variant (P.1) in November 2020. Currently, circulating variants of concern are Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron (B.1.1.529), whose earliest documented samples were detected in October 2021 and November 2021, respectively. Variants are associated with different clinical presentations, as shown by a study comparing the prevalence of symptoms between the Delta and Omicron waves in the UK.5 For instance, during the Omicron wave, users were more likely to report sore throat and hoarse voice and less likely to report at least one of the three classic COVID-19 symptoms (i.e. those included in the UK National Health Service guidelines: anosmia, fever and persistent cough) compared with the Delta wave.5 However, changes in COVID-19 symptoms across variants have not been evaluated for cutaneous manifestations. Anecdotally, dermatologists have noted fewer consultations for rashes during the Delta and even fewer during the Omicron wave,6 but data are needed to formally assess how cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection have changed with the different variants.

In this retrospective study, we report on the diagnostic value, frequency and duration of five cutaneous manifestations (acral, burning, erythematopapular and urticarial rash, and unusual hair loss) of SARS-CoV-2 by leveraging longitudinal self-reported information collected via the ZOE COVID Study app7 during the Delta and Omicron waves. Additionally, we investigated whether vaccination influenced the frequency of skin-related symptoms.

Materials and methods

The ZOE COVID Study app

Users of the ZOE COVID Study app7 were recruited through social media outreach and included anyone able to download and use the app, either themselves or by proxy. The app collects data on sign-up, including sex, age, ethnicity (Asian, black, Chinese, Middle East, mixed, other or white), height, weight, common disease status (e.g. eczema) and the use of medications (e.g. corticosteroids and immunosuppressants). Users could provide daily updates on the presence of 33 COVID-19-related symptoms (Table S1; see Supporting Information). These included five cutaneous manifestations: (i) red/purple sores or blisters on the feet or toes (acral rash); (ii) strange, unpleasant sensations like pins and needles or burning (burning rash); (iii) rash on the arm or torso (erythematopapular rash); (iv) red, itchy welts on the face or body or sudden swelling of the face or lips (urticarial rash); and (v) unusual hair loss. When a symptom was not reported we assumed that the user was not experiencing that symptom (passive reporting). Users could self-report if or when they had a SARS-CoV-2 test, how it was performed [e.g. PCR swab, lateral flow test (LFT), antibody testing] and the result. From 11 December 2020, users could also log information on vaccination, including the date of each administered dose.

Data curation

The data curation workflow was performed using ExeTera (v0.6.0b),8 a software specifically developed for handling the large volumes of data present in the dataset, followed by ad hoc R scripts to perform further data cleaning and the specific statistical analyses (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

This study included UK residents, reporting a numerically plausible age range between 1 and 90 years, and who entered data during the Delta wave (27 June to 27 November 2021) and/or the Omicron wave (20 December 2021 to the day of the last data dump before the presented analysis, 23 February 2022),5 either themselves or by proxy (data snapshot: 24 February 2022).

As the app does not perform any validation of user-inputted data at the time of logging, as done in our previous study3 we used the following criteria to exclude users reporting unreliable or extreme observations: for users 16 years old or older, height, weight or body mass index (BMI) outside the range of 1·1–2·2 m, 40–200 kg, and 15–55 kg m−2, respectively; for users younger than 16 years old, height, weight or BMI outside two SDs from the sample’s mean for each age group. We further excluded users who did not report their sex, users younger than 12 years old reporting being vaccinated (these individuals were not eligible for vaccination at the time of the study), and users younger than 16 years old reporting as being healthcare workers. Details on the data selection protocol are shown in Figure S1 (see Supporting Information).

A SARS-CoV-2-positive illness was defined as the period starting 14 days before a positive PCR or LFT SARS-CoV-2 test result, as done previously,9 and ending on the day the first negative test result was logged, provided there were no additional positive tests within a 45-day window from the negative test date. Positive test results within 45 days of each other were considered part of an ongoing illness. When no negative test result was logged within 45 days of a positive test, the end of the illness was fixed to 45 days after the last recorded positive test. We used a shorter window size compared with the 90 days used with earlier variants as there is mounting evidence that the Omicron reinfection window is considerably shorter than for Delta and prior variants.10 Due to this choice, during the Delta wave, we observed 66 users (0·1%) who logged a SARS-CoV-2-positive illness twice, with the first two positive test results no more than 134 days apart (median 69 days). As we could not confirm these were actual reinfections, only the first SARS-CoV-2-positive illness was retained. No double log of SARS-CoV-2-positive illnesses, and therefore of suspected reinfection, was recorded during the Omicron wave. Only symptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive illnesses were used in this study.

Due to the wide availability of free testing in the UK during the study period, distinct periods of symptomatic logging not accompanied by a positive PCR or LFT COVID-19 test (i.e. when the result was negative, or no result was logged) were considered non-SARS-CoV-2-related illnesses. A non-SARS-CoV-2-related illness started 14 days before the logging of the first symptom and ended with the first asymptomatic report, provided there were no further symptomatic assessments within a 14-day window.

To avoid biases due to users being able to log both SARS-CoV-2-positive illnesses and unrelated illnesses within the same wave, and to maximize the number of users with positive test results, we considered only the data entry for confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections. When users logged multiple non-SARS-CoV-2-related illnesses during the same wave, one was selected at random.

For each illness, the date of the last vaccination and the number of doses administered before the illness started were recorded. Users were considered vaccinated when they had at least two doses of vaccine, and the start of the recorded illness was at least 14 days but no more than 240 days (8 months) after the last dose, which is when vaccine effectiveness decreases for all three vaccines used in the UK.11

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using R (v4.1.0). Comparisons between categorical values were carried out using the Pearson χ2-test or Fisher exact test, as reported in the text. Comparisons between continuous values were carried out using the Wilcoxon test or, for BMI, using linear regression after correction for age and sex.

Due to the observational nature of our study, differences in users who logged during the Delta and Omicron waves were present. Therefore, to increase the robustness of our results, users logging during the Omicron wave were matched 1 : 1 to randomly selected users logging during the Delta wave on age, sex, vaccination status, and self-reporting a diagnosis of eczema. Overall, 72 269 and 3049 users who logged during the Delta and Omicron wave were discarded because no 1 : 1 match could be identified. Of the matched users, 1273 (0·3%) logged a SARS-CoV-2-positive illness during both the Delta and Omicron waves.

Associations between the presence or absence of self-reported cutaneous symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 test results were carried out through multivariate logistic regression. The covariates included were sex, age, BMI, ethnicity, self-reported diagnosis of eczema, vaccination status, and whether corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants were administered. Associations passing a Bonferroni-derived threshold of 0·05/5 = 0·01 were considered statistically significant.

The duration of each symptom was calculated as the difference between the dates on which the symptom was last and first logged. The durations of symptoms between waves were compared using the Wilcoxon test, and those passing a Bonferroni-derived threshold of 0·05/5 = 0·01 were considered statistically significant.

The association between the presence or absence of self-reported cutaneous symptoms and vaccination status was carried out using the Fisher exact test on a subset of SARS-CoV-2-positive users matched 1 : 1 for age, sex and self-reported diagnosis of eczema.

Plots were generated with the following R packages: forest plots with ggplot2 (v3.3.5), heatmaps with pheatmap (v1.0.12), and the plot showing the duration of skin-related symptoms with gghalves (v0.1.1). P-values in the plots were calculated using rstatix (v0.7.0) and displayed with ggprism (v1.0.3).

Results

Cutaneous symptoms: diagnostic value, frequency and duration

Longitudinal self-reported data were collected from 348 691 UK users matched 1 : 1 for age, sex, vaccination status and self-reported eczema diagnosis between the Delta and Omicron waves. They included 42 299 SARS-CoV-2 infections confirmed via PCR or LFT and 156 835 unrelated illnesses during the Delta wave (Table 1), and 75 580 confirmed infections and 123 554 unrelated illnesses during the Omicron wave (Table 2).

| All users | Delta wave | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Positive | Negative | P-value | ||

| Number | 348 691 | 199 134 | 42 299 | 156 835 | |

| Female | 233 396 (66·9) | 134 914 (67·8) | 26 216 (62·0) | 108 698 (69·3) | < 0·001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 46·5 (17·7) | 46·3 (17·6) | 44·6 (18·2) | 46·7 (17·4) | < 0·001 |

| Is vaccinated | – | 155 849 (78·3) | 31 556 (74·6) | 124 293 (79·3) | < 0·001 |

| BMI (kg m−2), mean SD | 26·0 (6·0) | 26·0 (6·1) | 25·8 (6·1) | 26·1 (6·1) | 0·24 |

| Acral rash | 2847 (0·8) | 1428 (0·7) | 456 (1·1) | 972 (0·6) | < 0·001 |

| Burning rash | 23 798 (6·8) | 12 491 (6·3) | 4792 (11·3) | 7699 (4·9) | < 0·001 |

| Erythematopapular rash | 10 383 (3·0) | 5219 (2·6) | 1633 (3·9) | 3586 (2·3) | < 0·001 |

| Unusual hair loss | 4982 (1·4) | 3207 (1·6) | 1030 (2·4) | 2177 (1·4) | < 0·001 |

| Urticarial rash | 7990 (2·3) | 3890 (2·0) | 1226 (2·9) | 2664 (1·7) | < 0·001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Asian | 4357 (1·2) | 2445 (1·2) | 567 (1·3) | 1878 (1·2) | < 0·001 |

| Black | 1271 (0·4) | 699 (0·4) | 166 (0·4) | 533 (0·3) | |

| Chinese | 1020 (0·3) | 578 (0·3) | 95 (0.2) | 483 (0·3) | |

| Middle East | 825 (0·2) | 475 (0·2) | 111 (0·3) | 364 (0.2) | |

| Mixed | 7242 (2.1) | 4146 (2.1) | 834 (2·0) | 3312 (2.1) | |

| Others | 1689 (0·5) | 984 (0·5) | 184 (0·4) | 800 (0·5) | |

| White | 331 407 (95·0) | 189 282 (95·1) | 40 230 (95·1) | 149 052 (95·0) | |

| Not applicable | 880 (0·3) | 525 (0·3) | 112 (0·3) | 413 (0·3) | |

| Has eczema | 44 853 (12·9) | 26 100 (13·1) | 4821 (11·4) | 21 279 (13·6) | < 0·001 |

| Corticosteroids | 24 073 (6·9) | 14 020 (7·0) | 2564 (6·1) | 11 456 (7·3) | < 0·001 |

| Immunosuppressants | 13 965 (4·0) | 8184 (4·1) | 1557 (3·7) | 6627 (4·2) | < 0·001 |

- The data are presented as the number (percentage) unless stated otherwise. Within each wave, differences between positive and negative users were assessed using: for cutaneous manifestation, multivariate logistic regression adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), self-reported diagnosis of eczema, and whether the users were taking corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants; for other binary values, χ2-test; for age, Wilcoxon test; for BMI, linear regression adjusting for age and sex.

| All users | Omicron | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Positive | Negative | P-value | ||

| Number | 348 691 | 199 134 | 75 580 | 123 554 | |

| Female | 233 396 (66·9) | 134 913 (67·7) | 48 818 (64·6) | 86 095 (69·7) | < 0·001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 46·5 (17·7) | 46·3 (17·6) | 44·1 (18·7) | 47·6 (16·8) | < 0·001 |

| Is vaccinated | – | 155 849 (78·3) | 56 857 (75·2) | 98 992 (80·1) | < 0·001 |

| BMI (kg m−2), mean (SD) | 26·0 (6·0) | 26·0 (6·0) | 25·5 (6·1) | 26·3 (6·0) | < 0·001 |

| Acral rash | 2847 (0·8) | 1471 (0·7) | 539 (0·7) | 932 (0·8) | 0·49 |

| Burning rash | 23 798 (6·8) | 12 023 (6·0) | 5408 (7·2) | 6615 (5·4) | < 0·001 |

| Erythematopapular rash | 10 383 (3·0) | 5310 (2·7) | 2072 (2·7) | 3238 (2·6) | 0·0075 |

| Unusual hair loss | 4982 (1·4) | 1976 (1·0) | 604 (0·8) | 1372 (1·1) | < 0·001 |

| Urticarial rash | 7990 (2·3) | 4218 (2.1) | 1752 (2·3) | 2466 (2·0) | < 0·001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Asian | 4357 (1·2) | 2425 (1·2) | 964 (1·3) | 1461 (1·2) | < 0·001 |

| Black | 1271 (0·4) | 742 (0·4) | 257 (0·3) | 485 (0·4) | |

| Chinese | 1020 (0·3) | 573 (0·3) | 253 (0·3) | 320 (0·3) | |

| Middle East | 825 (0.2) | 464 (0.2) | 169 (0.2) | 295 (0·2) | |

| Mixed | 7242 (2.1) | 4206 (2.1) | 1751 (2·3) | 2455 (2·0) | |

| Others | 1689 (0·5) | 972 (0·5) | 371 (0·5) | 601 (0·5) | |

| White | 331 407 (95·0) | 189 274 (95·0) | 71 642 (94·8) | 117 632 (95·2) | |

| Not applicable | 880 (0·3) | 478 (0.2) | 173 (0·2) | 305 (0·2) | |

| Has eczema | 44 853 (12·9) | 26 095 (13·1) | 9464 (12·5) | 16 631 (13·5) | < 0·001 |

| Corticosteroids | 24 073 (6·9) | 13 893 (7·0) | 4393 (5·8) | 9500 (7·7) | < 0·001 |

| Immunosuppressants | 13 965 (4·0) | 7985 (4·0) | 2584 (3·4) | 5401 (4·4) | < 0·001 |

- The data are presented as the number (percentage) unless stated otherwise. Within each wave, differences between positive and negative users were assessed using: for cutaneous manifestation, multivariate logistic regression adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), self-reported diagnosis of eczema, and whether the users were taking corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants; for other binary values, χ2-test; for age, Wilcoxon test; for BMI, linear regression adjusting for age and sex.

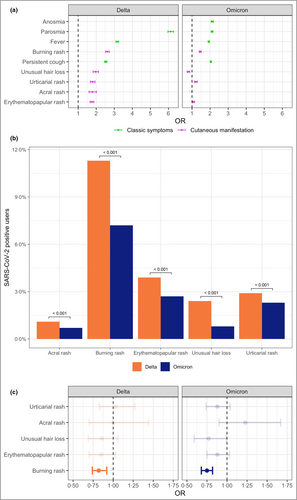

Cutaneous symptoms were reported by 7430 (17·6%) and 8632 (11·4%) infected and 14 041 (9·0%) and 11 805 (9·6%) noninfected users during the Delta and Omicron waves, respectively. We investigated their overall diagnostic value, confirming a significantly higher prevalence among users who tested positive compared with those who tested negative during both Delta [odds ratio (OR) 2·29, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2·22–2·36, P < 0·001] and Omicron (OR 1·29, 95% CI 1·26–1·33, P < 0·001) waves, with burning rash having the highest OR (OR 2·61, 95% CI 2·52–2·72, P < 0·001 for Delta and OR 1·46, 95% CI 1·40–1·51, P < 0·001 for Delta) (Table 3). In comparison, the ORs for fever and cough, well-known SARS-CoV-2 manifestations, were 3·17 (95% CI 3·09–3·24, P < 0·001) and 2·53 (95% CI 2·47–2·59, P < 0·001), respectively, for the Delta wave and 1·93 (95% CI 1·89–1·97, P < 0·001) and 2·04 (95% CI 2·00–2·08, P < 0·001) for the Omicron wave, suggesting a similar diagnostic value compared with skin, especially during Delta (Figure 1a).

| Delta wave | Omicron wave | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Acral rash | 1·79 (1·60–2·01) | < 0·001 | 0·96 (0·86–1·07) | 0·49 |

| Burning rash | 2·61 (2·52–2·72) | < 0·001 | 1·46 (1·40–1·51) | < 0·001 |

| Erythematopapular rash | 1·76 (1·66–1·87) | < 0·001 | 1·08 (1·02–1·14) | 0·0075 |

| Unusual hair loss | 1·97 (1·83–2·12) | < 0·001 | 0·80 (0·73–0·88) | < 0·001 |

| Urticarial rash | 1·80 (1·68–1·93) | < 0·001 | 1·21 (1·14–1·29) | < 0·001 |

- For each collected cutaneous manifestation of SARS-CoV-2, the table shows the odds ratio (OR) of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result along with its 95% confidence interval (CI) and P-value for the multivariate logistic regression after correction for age, sex, body mass index, diagnosis of eczema, vaccination status, and administration of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Users were considered vaccinated when they had at least two doses of vaccine and the start of the illness was at least 14 days but no more than 240 days (8 months) after the last dose. The analyses for the Delta and Omicron waves included 198 609 and 198 656 users, respectively.

The diagnostic value of all cutaneous symptoms was higher in the Delta compared with the Omicron wave (Table 3), in line with a change in the frequency of cutaneous symptoms across variants, as cutaneous manifestations were more common in the Delta wave compared with Omicron (17·6% vs. 11·4%, Fisher test: P < 0·001) (Figure 1b and Tables 1 and 2). For instance, acral rashes were the most common manifestation in confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 during the wildtype wave3 and decreased thereafter. They were reported by 3·1%, 1·1% and 0·7% of the infected users in the wildtype,3 Delta and Omicron waves, respectively (Fisher test: P < 0·001), and were diagnostic in the wildtype3 (OR 1·74, 95% CI 1·33–2·28, P < 0·001) and Delta waves (OR 1·79, 95% CI 1·60–2·01, P < 0·001) but not in the Omicron wave.

Additionally, all cutaneous manifestations (apart from acral rash) showed an average longer duration during the Delta wave than the Omicron wave (Wilcoxon test: P = 0·002) (Figure S2; see Supporting Information).

Timing of cutaneous symptoms in relation to other COVID-19 symptoms

In infected users, cutaneous symptoms clustered with other frequent symptoms, such as headache, runny nose, sore throat and sneezing (Figure S3; see Supporting Information). They were most often reported after other symptoms (61·5% and 55·8% for Delta and Omicron, respectively; Fisher test: P < 0·001), on average after 6 and 5 days for Delta and Omicron, respectively (Wilcoxon test: P < 0·001), or at the same time as other symptoms (37·8% for Delta and 43·0% for Omicron; Fisher test: P < 0·001). Only 0·5% and 0·8% of the infected users reported cutaneous manifestation as the first presentation in the Delta and Omicron waves, respectively (Fisher test: P = 0·01), on average 5 days before the next logged symptom in both waves. Similarly, only 0·2% and 0·4% of the infected users in the Delta and Omicron waves, respectively, logged a skin-related symptom as the only clinical sign of infection (Fisher test: P = 0·006).

Cutaneous symptoms in vaccinated and unvaccinated users

We compared the odds of developing a cutaneous symptom in vaccinated vs. unvaccinated users who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. The two groups were matched 1 : 1 for age, sex and self-reported eczema diagnosis, as vaccinated users were more likely than unvaccinated users to be female (OR 1·14, 95% CI 1·09–1·19, P < 0·001 and OR 1·15, 95% CI 1·11–1·19, for Delta and Omicron, respectively), older (median age 51 vs. 21 years, Wilcoxon test: P < 0·001; and median age 50 vs. 22 years, Wilcoxon test: P < 0·001, for Delta and Omicron, respectively), and more likely to self-report eczema (OR 1·22, 95% CI 1·14–1·30, P < 0·001 and OR 1·29, 95% CI 1·23–1·35, for Delta and Omicron, respectively). We observed that cutaneous symptoms were similar in the two groups, apart from the odds of burning rash, which were lower in vaccinated users (Figure 1c; and Table S2; see Supporting Information).

Discussion

In this study, we observed that the frequency of cutaneous manifestations and their diagnostic power were higher in the Delta than in the Omicron wave. While possible unmeasured confounders might be present, we believe that they are unlikely to be differently distributed between the populations in the two waves, and that cutaneous manifestations were genuinely more common in the Delta than in the Omicron wave. Indeed, changes in cutaneous manifestations across variants are expected as these were observed for other non-skin-related symptoms.5 Monitoring these changes may help in identifying the emergence of new variants and it is particularly important now that several national surveillance studies, including those involving genomic sequencing, have been scaled back or terminated.

Our findings also back up anecdotal clinical observations that rashes such as chilblains have presented less frequently to dermatologists during the Omicron relative to prior waves.6 While this could be due to a true biological decrease based on variants’ characteristics or to a previous exposure to the virus, an increasing familiarity with rashes as a part of COVID-19 presentation by both primary care physicians and the public, who found them less concerning and less worthy of referral to a specialist, cannot be ruled out. We could not directly compare the frequency of the currently collected skin-related symptoms with those collected during the wildtype wave,3 apart from acral rash, which was progressively less common in the Delta and Omicron waves. Indeed, in the previous study,3 erythematopapular and urticarial rash were collected together, and neither burning rash nor unusual hair loss was included in the list of symptoms.

Despite the observed decrease in frequency from the Delta to the Omicron wave, the ORs for skin-related symptoms remained comparable, in both waves, with those of more well-known COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever and cough. In contrast, the World Health Organization has not yet included cutaneous manifestations in its COVID-19 case definition of symptoms suspicious for SARS-CoV-2 infection,12 possibly leading to delayed or missed diagnoses.

We also observed that cutaneous symptoms clustered with other frequent symptoms and that < 2% of the users infected with SARS-CoV-2 reported them as the first or the only clinical sign. In our previous study,3 using a retrospective survey on COVID-19-related skin rashes during the wildtype wave, we observed that 21% of positive cases reported a skin-related symptom as the only clinical presentation and 17% as the first presenting symptom. This difference may be explained by the survey specifically targeting individuals aware of the link between skin-related symptoms and COVID-19, and who were asked to describe their symptoms in more detail.

Analogously, we observed a much shorter symptom duration during the Delta and Omicron waves compared with the wildtype wave.3 However, our current data suggest that users may interrupt logging after the acute phase of the infection, while the survey presented in our previous study,3 due to its retrospective nature, was able to record the entire duration of skin-related symptoms. Thus, the durations reported here may be an underestimation of a longer course of symptoms, which was correctly captured by ours and other studies.2, 3, 13

The mechanism of why symptoms differ between waves is still an area of active investigation, with tissue tropism and viral replication possibly contributing to this variation.14 For example, the Delta and Omicron waves show less tropism for the lung compared with the wildtype, and instead, upper respiratory symptoms such as sore throat and sneezing are common.5 In addition, many users may have experienced COVID-19 more than once, and their prior exposure and immunity may have altered the presentation of symptoms in further waves. While we have historical data for a subset of users, it is likely that many presented with an asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection or one that did not present any of the classic symptoms and was therefore never documented on the app, especially during the early waves when access to testing was very limited, making the comparison of symptoms between subsequent infections impossible.

Vaccination status has also been proposed to play a role in differences in symptoms over time, with infected vaccinated individuals reporting almost all COVID-19 symptoms less frequently than unvaccinated users.15 However, we observed, on a large scale, that there was no difference in skin-related symptoms between vaccinated and unvaccinated users with confirmed infection, apart from burning rash, which was less common after vaccination.

A major limitation of this study is that our sample represents a self-selected group of individuals, and, therefore, is not fully representative of the general population. A second limitation of this study is the self-reported nature of the data. However, in our previous study,3 using a reasonably large number of photographs (n = 260) blindly assessed by four dermatologists, we showed that a large majority of individuals (86%) were able to self-identify cutaneous manifestation likely to be related to COVID-19 infection. Additionally, assigning infection to a specific variant based on the variance prevalence at the time in the UK population rather than using individual sequencing information may introduce misclassifications. However, individual sequencing was not feasible due to the size of this study, and data from the UK Health Security Agency confirmed that, within the reported periods, more than 70% of sequenced cases of SARS-CoV-2 were either Delta or Omicron.16

In summary, this study suggests that changes in cutaneous manifestations may help to identify new variants and provide additional evidence to support their inclusion in the list of clinically relevant COVID-19 symptoms.

Funding sources

ZOE Ltd provided in-kind support for all aspects of building, running and supporting the app and service to all users worldwide. Investigators received support from the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council/British Heart Foundation, Alzheimer’s Society, European Union, National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), Chronic Disease Research Foundation, and the NIHR-funded BioResource, Clinical Research Facility and Biomedical Research Council based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London. This work was also supported by the UK Research and Innovation London Medical Imaging & Artificial Intelligence Centre for Value Based Healthcare.

Conflicts of interest

J.W. is an employee of ZOE Ltd. T.D.S. is a cofounder and shareholder of ZOE Ltd. E.E.F. is an author for UpToDate on COVID-19 Dermatology, is the principal investigator of the COVID-19 Dermatology Registry, and serves on the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Task Force. The other authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Alessia Visconti: Methodology; data curation and analysis; original draft (lead); writing – review and editing. Benjamin Murray: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (lead); writing – review and editing (supporting). Niccolo Rossi: Visualization (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Jonathan Wolf: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (lead). Sebastien Ourselin: Funding acquisition (equal). Tim Spector: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (lead). Esther Freeman: Writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing. Veronique Bataille: Conceptualization (co-lead), writing – review and editing. Mario Falchi: Conceptualization (lead); funding acquisition (supporting); methodology (equal); supervision (lead); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting).

Open Research

Data availability

The data collected in the app are being shared with other health researchers through the National Health Service-funded Health Data Research UK (HDRUK)/SAIL consortium, housed in the UK Secure e-Research Platform in Swansea. Anonymized data collected by the symptom tracker app can be shared with researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal via HDRUK, provided the request is made according to their protocols and is in the public interest (https://healthdatagateway.org/detail/9b604483-9cdc-41b2-b82c-14ee3dd705f6). Data updates can be found at https://covid.joinzoe.com.

The study was approved by the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee REMAS ID 18210, review reference LRS-19/20-18210. All app users provided informed consent, either themselves or by proxy.