A guide to outcome evaluation of simulation-based education programmes in low and middle-income countries

Abstract

Evaluation is a vital part of any learning activity and is essential to optimize and improve educational programmes. It should be considered and prioritized prior to the implementation of any learning activity. However, comprehensive programme evaluation is rarely conducted, and there are numerous barriers to high-quality evaluation. This review provides a framework for conducting outcome evaluation of simulation-based education programmes in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). The basis of evaluation, including core ideas of theory, purpose and structure are outlined, followed by an examination of the levels and healthcare applications of the Kirkpatrick model of evaluation. Then, methods of conducting evaluation of simulation-based education in LMICs are discussed through the lens of a successful surgical simulation programme in Myanmar, a lower-middle-income country. The programme involved the evaluation of 11 courses over 4 years in Myanmar and demonstrated evaluation at the highest level of the Kirkpatrick model. Reviewing this programme provides a bridge between evaluation theory and practical implementation. A range of evaluation methods are outlined, including surveys, interviews, and clinical outcome measurement. The importance of a mixed-methods approach, enabling triangulation of quantitative and qualitative analysis, is highlighted, as are methods of analysing data, including statistical and thematic analysis. Finally, issues and challenges of conducting evaluation are considered, as well as strategies to overcome these barriers. Ultimately, this review informs readers about evaluation theory and methods, grounded in a practical application, to enable other educators in low-resource settings to evaluate their own activities.

Introduction

Evaluation is defined as ‘an examination conducted to assist in improving a programme and other programmes having the same general purpose’, and is an essential component of any learning programme.1 Its scope ranges from appraisal of individual teaching episodes to analysis of entire curricula.2 Evaluation is necessary to optimize and improve educational programmes and may serve a variety of purposes beyond this. Simulation describes a technique used ‘to replace or amplify real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the world in a fully interactive manner’.3 Low and middle-income countries (LMICs), currently defined by the World Bank as countries with a gross national income per capita less than $13846USD per year, have limited access to simulation-based education (SBE).4, 5 This review aims to utilize our experience conducting SBE programmes in Myanmar (a lower-middle-income country) to provide a framework for designing evaluation processes in similar settings.6, 7 Core topics and relevant educational theory are described, including the Kirkpatrick model of evaluation – an industry concept that has been successfully applied in multiple settings of medical education.8-10 The benefits of evaluation and its important relationship with programme logic and planning are discussed. Subsequently, a variety of evaluation approaches are described in the context of our own programme, as well as strategies to address common challenges. We outline a versatile evaluation approach which may be applied to other educational interventions in the similar settings of other LMICs.

Overview of relevant theory

Evaluation purpose

Evaluation focuses on whether programmes are working as intended or resulting in unintended consequences.1, 2 It may be formative (used to alter, modify, and improve learning) or summative (judges the quality of the programme in its entirety).11 Evaluation may improve programme implementation, resource management and academic standards, and may form the basis of acquiring funding and support for further initiatives.12, 13 Evaluation principles apply to any organized educational activity, including individual sessions and workshops or entire courses and curricula.2

Evaluation, assessment and research

The terms ‘evaluation’ and ‘assessment’ are often used interchangeably.12 However, assessment aims to measure individual learner's achievements, while evaluation focuses on the programme itself.1, 14 This is an important distinction as this review aims to provide the framework of an evaluation strategy for simulation based surgical programmes, rather than to assess learners using simulation.

Evaluation and research share many aspects of methodology but differ principally in their intent.15 Evaluations collect evidence to make decisions about programmes in their specific context, whereas research intends to contribute to the larger body of scientific literature. Historically, evaluation results were not necessarily published, but growing interest in translational research has resulted in a greater focus on evaluation studies, including in LMIC settings.7, 16-19 Publishing evaluations disseminates information for use in similar contexts.

The Kirkpatrick model of evaluation

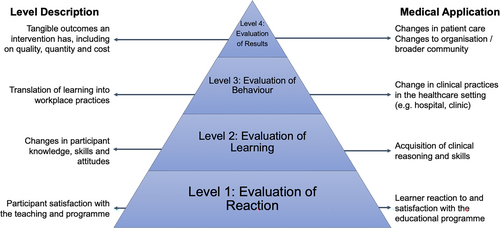

The Kirkpatrick model of evaluation, an educational model first described in 1959 for corporate learning and development, has been widely applied to medical education and is endorsed by the World Health Organisation.2, 8, 20-24 This includes within the field of technology-enhanced simulation training.25-27 The Kirkpatrick model consists of four levels of outcome evaluation, which are defined as reaction, learning, behaviour, and results.8, 28 Adaptations of the model have been created specifically for healthcare settings (Fig. 1).30 This focus on outcome and impact evaluation is distinct from evaluation methods which focus on the design and implementation phases.31, 32 The model was updated in 2016 to include additional principles centred on evaluation planning, stakeholder engagement and evidence of efficacy.33, 34

Higher levels of evaluation are increasingly complex but provide valuable results.28 While all levels should be considered in programme evaluation, in practice very few evaluations are comprehensive and appraise the programme's impact on clinical outcomes (Level 4).22, 28, 35 This is particularly true of studies focused on SBE, and can be attributed to the increased difficulty, time and cost required to evaluate at the higher levels.25, 28, 33 A review of simulation and debriefing in healthcare education, conducted by Johnston et al. in 2018, found no studies evaluating Level 4 of the model.25 However, appropriate planning enables collection of qualitative and quantitative data to facilitate a comprehensive evaluation, including all levels, as was achieved for our intussusception project in Myanmar.7, 36

The Kirkpatrick model has been challenged for several reasons.30, 37, 38 For example, Allen et al.30 highlighted that the focus on outcome evaluation means there is little consideration of how and why outcomes occur, and of the unintended impacts of programmes.30 However, while such challenges provide insight into potential shortcomings of the Kirkpatrick model, it remains a useful framework for evaluation in an LMIC setting.20

Programme theory and logic models

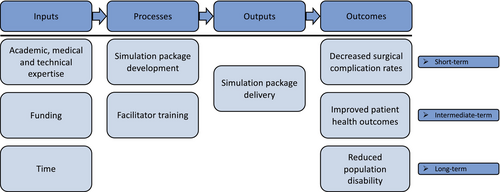

Programme logic can be used to inform programme implementation, monitoring, and evaluation, and should be considered in the design phase of a project.2 The development of a logic model, based on ideas of programme theory, is useful to create a practical evaluation framework.39 A logic model is a schematic representation describing a programme's function in terms of inputs, processes, outputs and outcomes.2, 39 Outcomes can be further divided into short, intermediate, and long-term outcomes (Fig. 2). Logic models may show how one programme feature affects another,40 and allow for systematic evaluation of each step in the causal chain. An outcomes hierarchy should first be developed, with evaluators starting with the desired impacts, allowing the activities and evaluation to be synergistically designed to support these goals.39 This complements Kirkpatrick's views that ‘trainers should begin by considering the desired results’.28

Causal attribution

International development projects, and particularly educational programmes, are highly complex and dependent on complicated networks of factors.41 As such, it is often difficult to attribute cause to the educational programme. While Programme Logic Models allow evaluation to be designed based on the desired goal, multiple feedback loops may occur and can make interpretation of the results challenging.39 Causal analysis should ideally consist of three main elements: congruence, comparisons, and critical review.39 Congruence refers to whether the outcome matches the programme theory, while comparison refers to what would have happened without the intervention. Finally, critical review focuses on whether there are other plausible explanations of the results.

Conducting programme evaluation

Programme evaluation may be divided into eight primary activities (Table 1).13

| Evaluation activity | Description |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Application of evaluation principles with simulation-based education in a lower-middle-income country

We have significant experience conducting SBE initiatives in a lower-middle-income country, the process of which has been described in detail elsewhere.6, 7, 36, 42 In brief, a multidisciplinary team designed and delivered 11 SBE courses in partnership with local paediatric surgeons and the University of Medicine 1 in Yangon, Myanmar, over a 4-year period.6 These included scenario-based simulation, part-task trainers, and laparoscopic simulation.42 Evaluation was conducted to optimize programme outcomes and guide future initiatives in the region. A mixed-methods approach was utilized, including clinical outcome measures, questionnaires, Likert-type scales, interviews and focus groups.6 In one workshop, the air enema technique for intussusception was introduced using a unique simulator.7, 43 For this programme, Level 4 of the Kirkpatrick model of evaluation was demonstrated and sustained: a significant reduction in the operative intervention rate from 82.5% to 55.8% pre- and post-implementation (n = 208, P = 0.0006) was observed. Successfully evaluating this improvement was facilitated by an ongoing partnership with local colleagues, which enabled cooperation for data collection, management and analysis, as well as the educational programme itself. Prior to commencement, a detailed needs analysis was conducted, which facilitated the establishment of learning and evaluation goals with local educational leaders. This was an element we found to be critical to the programme's success.

Evaluation methods

Methods of programme evaluation may be used sequentially or in parallel.2, 44, 45 Parallel implementation, using multiple methods concurrently, facilitates the use of different data sources to create a comprehensive evaluation.2

Mixed-methods evaluation

Mixed-methods evaluation enables triangulation of multiple methods and data sources to develop a comprehensive understanding of phenomena and reduce bias.44, 46 It has potential for increased validity and more insightful understandings.46, 47 Often complementary quantitative data (measures of values or counts) and qualitative data (non-numerical data, e.g., descriptions, experiences) are used. Quantitative data provides an excellent opportunity to determine how variables may be related, while qualitative data can provide information to explain why these relationships exist.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires are a practical, inexpensive, and timely method of collecting participant perspectives, qualities which are particularly advantageous in LMICs. They may be paper-based or online. Questionnaires were particularly useful to evaluate our programme's educational sessions and methods. The programme included a ‘flipped classroom’ approach, utilizing pre-recorded videos and reading assignments for independent learning prior to educational activities.48 This preserves in-person time for the application of acquired knowledge, and encourages higher-order thinking and active participation from students.48-50 Questionnaires at the start of the learning activity, and learner self-reflection, facilitated evaluation of this approach.51 Based on participant feedback, we determined that our flipped classroom approach increased engagement and motivation in educational sessions. This is consistent with emerging evidence for the technique in medical education, with a systematic review by Chen et al. outlining the positive perceptions and attitudes of students towards flipped classrooms.50 In accordance with feedback theory, questionnaires should be completed immediately after the activity, or in the case of a longer course, after each individual day.52 If delayed, the accuracy of the data may be altered and the response rate jeopardized.53

Questionnaires – measuring participant reaction and satisfaction

Questionnaires may include Likert-type scales to succinctly evaluate participant experiences with SBE, for example, rating the activity's applicability and utility for future practice. They should be anonymous to maximize accuracy. A template of a satisfaction questionnaire can be found in Document S1. Relative metric scales (where participants draw a point on a line rather than selecting a discrete option) have been suggested to represent participant beliefs more accurately when compared with categorical data (because rounding is avoided).54, 55 However, due to the lack of consensus in the literature, and additional difficulties of a relative metric approach, we recommend using a standard numerical scale.55

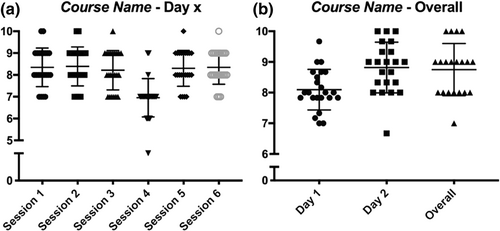

Satisfaction questionnaires directly address Kirkpatrick's first level of evaluation: participant reaction. Their analysis enables review and refinement of programme content that is rated as less useful, for example ‘Session 4’ in Figure 3. Such a rating system has proven to be a valuable and widely-used source of evaluation evidence.56, 57

When analysing results, the response range should be noted as this may indicate a more honest (and therefore valid) evaluation. In our experience, the use of anonymously completed scales offers sufficient spread of data and represents participants' true experience.6 The large range of responses6, 42 also challenges established dogma that only positive responses will be obtained in this setting.

Questionnaires – measuring participant knowledge

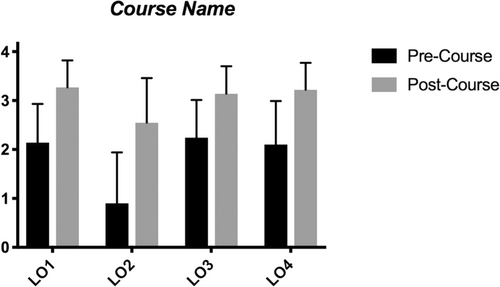

We utilized pre- and post-course five-point Likert-type rating scales (Fig. 4) to evaluate achievement of learning objectives following the programme. Additional examples of rating scales are included in Document S2 and Document S3. This data can be analysed to reveal differences in self-reported skills pre- and post-course. Such a method formalizes Kirkpatrick's second level, the evaluation of learning, with the participants’ confidence often also improving in various skills.6

Questionnaires – conducting statistical analysis

Various statistical methods may be used to determine significance and association between different variables.36, 58 Educators should consider factors including variable type, whether data is paired, and the distribution of data to guide the choice of test. Commonly used tests include Mann–Whitney tests (for unpaired, non-parametric data) and Wilcoxon signed-rank test (for paired, non-parametric data).58 As an example, Figure 5 reveals statistically significant improvements in all learning objectives (P < 0.05). Presenting this data can be a powerful tool to demonstrate the effectiveness of the educational activity.

As well as addressing the first two levels of the Kirkpatrick model, pre- and post-course evaluation strategies can also investigate the third level – evaluation of behaviour. Further evaluation with surveys in the 3–6 months following the programme may provide insight into change in practice through targeted enquiry. Alternatively, if participant confidence and skills have improved significantly post-course, a return to baseline in retention surveys would suggest there is little ongoing practice of the relevant skills. This finding would reflect a need to support ongoing and repeated practice of skills to enable long-term educational impact.

Questionnaires – qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis can be used to determine patterns of meaning in the questionnaire data.44 In our experience, open-ended questions such as ‘What was the best/worst aspect of the course?’ generate important feedback that could be otherwise missed by closed questioning. Thematic analysis, one form of qualitative analysis, involves iteratively coding the data to guide the conceptualisation of themes, or patterns of meaning.59 This facilitates improved understanding of phenomena.60 Software programmes can organize the analysis, and the educator can conceptualize and refine themes with the support of the wider research group.

Qualitative analysis can be utilized to evaluate participant reaction (Kirkpatrick level 1), knowledge (Kirkpatrick level 2) and provide insight into workplace practices (Kirkpatrick level 3), subsequently enabling further course refinement.

Individual interviews and focus groups

Interviews and focus groups facilitate exploration of new themes and planning for future educational initiatives.61 Importantly, they provide insight into how and why evaluation outcomes have occurred.30 Additional benefits include the abilities to validate other evaluation methods, adapt programmes to specific contexts, and identify future faculty collaborators. These qualities are particularly beneficial in an LMIC, where external course coordinators may lack in-depth understanding of contextual nuances. These methods should include people from all aspects of the programme to ensure that all stakeholders are represented in the evaluation and future planning process.

Methods to determine clinical impact

The desired clinical impact is the most difficult aspect of a programme to evaluate.28 Educational programmes are highly complex, and it is impossible to control all variables. For the intussusception component of our programme, a clinical evaluation was conducted by comparing outcomes for children with intussusception before and after programme implementation.7, 36 This is an example of SBE being successfully applied to an LMIC setting with a resultant change in clinical outcomes. When planning educational interventions, potential clinical outcome measures that could be linked to the activity should be explored with all stakeholders.

Issues to consider in evaluation

Integration of programme and evaluation planning

Programme planning and evaluation are highly interrelated so should be developed concurrently.2 When developing programmes, use of a logic model allows relevant and measurable objectives to be identified, enabling credible evaluation. Documenting these objectives will reveal the evaluation domains necessary to undertake and guide the planning and implementation of the learning activity.

Ethics in evaluation

Ethical obligations of evaluation studies include seven ethical standards drawn from a number of national bodies, Table 2.1 Ultimately, it is the evaluator's responsibility to work ethically within regulations and complete necessary Human Research Ethics Committee submissions.

| Ethical principle | Description |

|---|---|

|

Evaluators should be focused on serving the programme participants and society. |

|

Formal agreements which address protocols, data access and clear communication to participants should be made. |

|

Rights such as informed consent, confidentiality, and dignity should be considered. |

|

Programmes should be accurately portrayed, regardless of desired outcomes. |

|

Evaluation should benefit not only the programme and its sponsors, but also the wider community and public. |

|

Conflicts of interest should always be disclosed and resolved if possible. |

|

Overt expenditures as well as hidden costs should be documented. |

Challenges and common pitfalls in evaluation

Timeliness of analysis

Time between programme completion and evaluation data analysis should be minimized. For programmes where visiting teams are involved, data should be made available prior to departure, facilitating valuable faculty discussions, decision-making and planning. This should be prioritized over producing a final report.

Challenges of questionnaires

While we utilize questionnaires for programme evaluation, they have some disadvantages.44 These include questionnaire fatigue resulting in low response rate. This issue and others, as well as potential solutions, are outlined in Table 3.

| Issue | Description | Potential solution |

|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire fatigue and low response rates |

|

|

| Limited response options |

|

|

However, in our experience simple questionnaires are often sufficient to gain insight into the value of programmes without significant participant burden.

Additional considerations for evaluations in low and middle-income countries

Evaluations in LMICs should ideally be conducted with equivalent rigour to those conducted in high-income countries (HIC). However, there are context-specific factors to consider in the planning and execution phases. These factors are often complex and should be given due consideration in each unique setting.

Local capacity

Evaluations, like programmes more broadly, should ideally be led and conducted by local stakeholders. This stance is in line with the movement to decolonise global health, as well as the importance of contextual knowledge for evaluation.65, 66 However, this can pose challenges in some settings, as evaluation often requires significant human resources and time. As a result, the workforce challenges faced by LMICs may be an impediment to conducting evaluation.67 It may be difficult to find time to collect evaluation data, particularly interview and clinical data. This challenge can be addressed partially by LMIC-HIC collaborations like the one described in this article, where high-income actors can dedicate time to the evaluation process. In cases where a collaboration is taking place, LMIC leadership, perspectives and expertise should be prioritized.65

Resources

Evaluation data from surveys, interviews and clinical settings can often be collected with limited physical resources. However, measurement of outcomes can be additionally challenged by the absence of sufficient documentation and health informatics systems in some settings.68 Furthermore, data analysis often requires access to software and training which may not be available in all settings.69 Many of these challenges can also be targeted through collaborations, where high-income actors can facilitate ongoing access to the necessary resources.16

Sustainability

High-quality SBE requires ongoing and repeated practice, meaning consideration for the longevity of programmes in LMICs is critical.70 Ongoing evaluations are also pivotal as they can be used to judge programme effectiveness over time.71 This information can then guide programme changes and justify its ongoing use. Short or sporadic evaluations conducted by a visiting team have potential to be insufficient, with little consideration for a long-term evaluation strategy. Ongoing evaluation requires both evaluation skills and processes to be present long-term. As such, when LMIC-HIC collaborations are conducted, consideration should be given to the maintenance of evaluation. In some cases, train the trainer approaches can be used to upscale local educational and evaluation expertise.72 In the case of our project, sustainability was achieved through a gradual handover of responsibilities to local colleagues.7

Conclusion

Conducting a comprehensive evaluation is an integral component of educational programmes and necessary to optimize impact. However, evaluations need to be rigorously designed, constructed and implemented in partnership with local stakeholders. This review provides an overview of evaluation theory and practical implementation, including our approach for the collaborative evaluation of SBE in LMICs. This framework uses multiple methods in parallel, which increases the validity of results, and overcomes many of the shortcomings of each individual method. It is also practically feasible to conduct, a consideration which is important for work in low-resource settings. Finally, it has proven effective in our own practice described in this piece. Ultimately, this review outlines a framework for conducting a robust and practical evaluation of SBE programmes in LMICs, information which educators can use to guide similar programmes in other settings.

Author contributions

Samuel JA Robinson: Methodology; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Yin Mar Oo: Investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision. Damir Ljuhar: Investigation; methodology; project administration; writing – original draft. Elizabeth McLeod: Investigation; methodology; project administration; writing – original draft. Maurizio Pacilli: Conceptualization; methodology; supervision; writing – review and editing. Ramesh M Nataraja: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; visualization; writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgement

Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley - Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Elizabeth McLeod is an Editorial Board member of ANZ Journal of Surgery and a co-author of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.