Introducing peanut early in life – Ready for the general population?

The LEAP study1 elegantly supplied evidence that early and regular peanut introduction into the diet of infants with severe atopic eczema or egg allergy, or both (at-risk population) as early as by age 4–10 months dramatically reduces the prevalence of peanut allergy by the age of 5 years by 81%. This protection persists after 1 year of peanut avoidance, even in high-risk children with peanut-specific IgE.

Despite this impressive outcome, the practical implementation remained controversial.2, 3 The EAACI allergy prevention guideline provides a conditional recommendation to early introduction of peanut protein in the general population if prevalence of peanut allergy is high in the population4 But they lack recommendations for countries with a low prevalence. Thus, the S3 guideline for allergy prevention for German-speaking countries recommended early peanut introduction only for high-risk (Atopic eczema) children of families that regularly eat peanuts, if a peanut allergy is excluded via testing. This procedure inevitably further delays peanut introduction and also ignores novel better suited technologies like the basophil activation test.5 Similarly, an expert panel recommendation of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases from 2017 advocated for the early introduction (4–6 months) of peanut protein exclusively to high-risk groups after peanut allergy screening.2 Others recommended a broader range of potentially allergenic foods for all infants without restriction for risk status and pre-assessment.3 However, issues remained because the definition of peanut allergy in at-risk populations differs relevantly. Recent data from a general pediatric population showed that an introduction of allergenic foods (peanut, cow's milk, wheat, and egg) by the age of 3 months revealed a statistically significant reduction of food allergy in general and peanut allergy specifically at 36 months (60% reduction).6 In the EAT study,7 six allergenic foods were introduced from 3 months of age, and by 3 years of age, a 20%, statistically non-significant reduction in food allergy to one or more of the six foods was described. The dose of food exposure per week was 2 g of peanut protein twice weekly in EAT, while in the PreventADALL study6 the four foods should be given as tastes at least 4 days per week. By using a more liberal approach concerning the overall weekly dose of each food, the latter study succeeded with a high treatment adherence effect, and thus achieving significance levels in an intention-to-treat analysis. In the EAT study, while per-protocol analysis yielded significance of the early peanut introduction (0% vs. 2.5%), the intention-to-treat analysis failed, most likely based on the low treatment adherence factor.

In an interesting statistical approach, the authors from LEAP and EAT compiled their data enriched by different risk strata (eczema and its severity, ethnicity, egg allergy, baseline IgE) in order to achieve increased generalizability of the intervention for the whole population.8 The approach of patient-level meta-analysis using combined populations does not per se reflect the general population, but pooled analysis increases the power to analyze subgroups. The results are exciting as they suggest an overall effect that is more pronounced if the introduction starts earlier. They also suggest that the success of peanut introduction is independent of ethnicity, peanut-specific IgE, and severity of eczema. Logan et al.8 also challenges the conclusion that primary prevention of peanut allergy is more effective in a high-risk population and instead favors the concept that adherence/amount or frequency (not known yet) of peanut consumption defines the efficacy of early introduction.

Major arguments against an early introduction of peanut in low risk groups in Europe include the lack of well controlled studies, the rather moderate reduction in Australia despite of an efficient introduction strategy and indications for an increase in the numbers of tree nut aspirations in Australia.9 Another issue is the lack of knowledge on the amount of peanut that needs to be introduced to be effective. Continental Europe in general did not favour food avoidance policies in mothers and children and prevalence rates of peanut allergy are low compared to North America, Australia, and the United Kingdom with more or less extensive avoidance recommendations in the past. Therefore, the impact of an active recommendation in Europe may not be as effective but lead to many policies and use of resources with very little additional impact on the prevalence of peanut allergy but a direct negative impact on the quality of life.

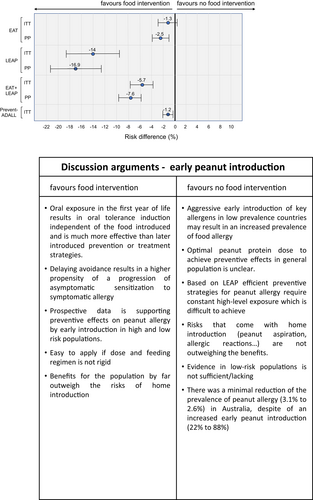

In conclusion the fact that both study approaches by PreventADALL and LEAP+EAT yield similar effects, highly reassures the current experimental analysis (Figure 1)8 which provides new data in support of the generalizability of early peanut introduction in the general populations using a statistical post hoc/meta-analysis approach. This further strengthens the concept of an early introduction of age-appropriate (solid) food preparations instead of an avoidance of common allergenic foods.

This figure is extracted from figure 4 of the manuscript by Logan et al.8 and completed with data on the very same topic taken from Skjerven et al.6 (PreventADALL study). The figure represents a forest plot of peanut allergy prevention effect sizes among three different study populations (EAT, LEAP, PreventADALL) and the combination of the EAT and the LEAP study. Risk differences in peanut allergy are annotated above the marker, that covers 95% CI. Relative risk differences (%) are related to early peanut intervention compared to the control group (peanut avoidance) and determined by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) methods.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this publication.