The urgent need for a harmonized severity scoring system for acute allergic reactions

Abstract

The accurate assessment and communication of the severity of acute allergic reactions are important to patients, clinicians, researchers, the food industry, and public health and regulatory authorities. Severity has different meanings to different stakeholders with patients and clinicians rating the significance of particular symptoms very differently. Many severity scoring systems have been generated, most focusing on the severity of reactions following exposure to a limited group of allergens. They are heterogeneous in format, none has used an accepted developmental approach, and none has been validated. Their wide range of outcome formats has led to difficulties with interpretation and application. Therefore, there is a persisting need for an appropriately developed and validated severity scoring system for allergic reactions that work across the range of allergenic triggers and address the needs of different stakeholder groups. We propose a novel approach to develop and then validate a harmonized scoring system for acute allergic reactions, based on a data-driven method that is informed by clinical and patient experience and other stakeholders’ perspectives. We envisage two formats: (i) a numerical score giving a continuum from mild to severe reactions that are clinically meaningful and are useful for allergy healthcare professionals and researchers, and (ii) a three-grade-based ordinal format that is simple enough to be used and understood by other professionals and patients. Testing of reliability and validity of the new approach in a range of settings and populations will allow eventual implementation of a standardized scoring system in clinical studies and routine practice.

Abstract

1 INTRODUCTION

IgE-mediated allergy affects people of all age groups across the world.1 Allergic reactions are triggered by a wide range of allergen sources including foods, stinging insects, house dust mite, pollens, molds, drugs, and animal dander, causing manifestations affecting many different organ systems. Although most are IgE-mediated allergic reactions, there are overlapping presentations with other pathophysiologies (eg, anaphylactoid reactions). Severity of reactions vary, both between episodes within the same individual and between different individuals.2 Symptoms range from mild, self-limiting local reactions to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Perception is critical, with different stakeholders often having very different views about the apparent severity of the same reaction. These differences are important because the severity of a reaction guides both the immediate and long-term management of the patient.3 It is therefore vital to be able to describe accurately the severity of previous reactions to optimize both immediate care decisions and ongoing patient management. Moreover, there is a need to grade severity, to standardize patient monitoring, and to define severity in participants in clinical studies, such as immunomodulation therapy, as well as facilitate risk assessment and management by, for example, the food industry and public health authorities.

Many scoring systems have been developed to describe the severity of allergic reactions for venom,4, 5 food,6-11 drugs,12, 13 and adverse reactions to allergen immunotherapy.14, 15 Some specifically mention anaphylactoid reactions12, 13; at least some of these are likely to represent anaphylaxis (absence of specific IgE is not reported) and as so are included. Although these have all been developed to assist patients and healthcare professionals correctly manage reactions, there is considerable heterogeneity in the approaches employed in these systems. Consequently, we lack a single, standardized approach to quantifying the severity of allergic reactions to all triggers that can be used by all stakeholders. The European Union-funded iFAAM project, in collaboration with a task force of the EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Initiative, critically reviewed the currently available systems, considered the challenges to generating scoring systems and proposed an approach to developing a harmonized system to quantify the severity of allergic reactions. In addition, recommendations were made as to how such a new scoring system could be validated. Our ultimate aim was in due course to develop a new severity scoring system for allergic reactions that can be utilized in different scenarios, in order to improve patient care and facilitate the needs of other stakeholders.

2 WHY DO WE NEED A SEVERITY SCORING SYSTEM FOR ACUTE ALLERGIC REACTIONS?

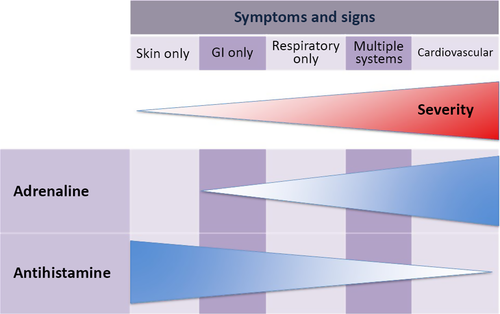

A severity scoring system for allergic reactions may assist clinicians in at least two ways: providing a summary of a reaction reported by a patient or carers and providing a summary of an allergic reaction within the context of a challenge or immunotherapy undertaken in a clinical environment. The score should contribute to determining appropriate emergency treatment plans. Other important stakeholders are likely to have somewhat different views as to why a harmonized severity scoring system is required for allergic reactions (Table 1). For example, a patient might better utilize a simpler system that can be readily recalled in an emergency and directly links to emergency therapy (Figure 1). Although the level of detail required by each stakeholder may vary, there is an intrinsic benefit in having a harmonized system that all stakeholders can utilize. This would facilitate communication in terms of the nature of specific reactions and how they should be managed. At its simplest level, a harmonized scoring system could divide allergic reactions into a small number of grades with very different severities on the basis of easily recognized symptoms and signs. Each major grade might have a number of subgrades to provide additional detail that might be useful to an allergy healthcare professional or researcher. A validated disease severity scoring system could be used both to standardize patient monitoring and to define patient cohorts in clinical studies.

| Stakeholder | Purpose | Essentials of the system |

|---|---|---|

| Patients and their carers | Risk awareness, recognition of symptoms of allergic reaction, recognition of seriousness and decision of type of self-treatment, and reassurance. | Requires a simple, easy-to-remember system to facilitate direct linkage of presentation to management. |

| Emergency department, family doctors, and other healthcare professionals | Assessment for acute and long-term management according to their competences, decisions about need to refer to specialist, and educational purposes | Requires a simple, easy-to-remember system to facilitate emergency management. |

| Allergy healthcare specialists | Assessment for acute and long-term management, risk assessment, and education of patients. | To document the reaction in detail to allow documentation and communication. |

| Food industry | Increase awareness on anaphylaxis, risk assessment of products, and risk management | Client-facing sectors (eg, restaurants) need a simple framework to manage allergic reactions. Risk assessors and managers need numerical scores that can be incorporated into probabilistic models of allergen risk. |

| Public health authorities | Increase awareness on anaphylaxis, to assess outcomes of health policies, funding allocation, health policy prioritization, and cost-effectiveness assessment, improve allergic reaction codification, facilitate epinephrine availability, education on anaphylaxis management for lay people (eg, teachers, children day carers, and airline cabin crew) | Require a simple, easy-to-understand system that can be used by nonhealthcare professionals. For regulators, a more sophisticated numerical score incorporating probabilistic models of allergen risk would be required. |

| Food, hospitality, and catering industries | Increase awareness on anaphylaxis, risk assessment of products, and risk management | The food industry (eg, restaurants) needs a simple framework to manage allergic reactions. Risk assessors and managers need numerical scores that can be incorporated in probabilistic models of allergen risk. |

| Researchers | Harmonize terminology in observational and interventional studies, aid comparison of data, and interpretation of mechanistic studies | System needs to document the reaction with increased granularity to allow definition, segmentation, and analysis |

As severity increases with increasingly severe symptoms, epinephrine is more likely to be indicated. The exact symptoms when epinephrine is indicated need to be individualized for different patients and for different situations by their healthcare professional as each will have a different risk profile. The figure is only an illustration with different severity sequences seen for different allergens and different patients. Additionally, therapies such as oxygen and corticosteroids may also be indicated. Figure reproduced with permission from Muraro et al.3

3 THE MEANING OR PERCEPTION OF SEVERITY IN RELATION TO ACUTE ALLERGIC REACTIONS

The term severity has different meanings to different subgroups of patients, to healthcare professionals, researchers, the food industry, public health authorities, or other stakeholders. All these perspectives need to be explored to understand the differing needs and concerns of each of these groups. A dictionary definition describes severity “as the degree of affliction suffered due to a condition or stressor” or “the degree of pain or harm from a medical condition”. A severe reaction should be considered either as one causing disruption to the activities of daily life or as an event that leads to an otherwise unanticipated healthcare utilization.

It is important to recognize that “severity” is a continuum, which may be dynamic: A person having a mild reaction (eg, mild angioedema) may progress to severe symptoms (eg, bronchospasm) within a few minutes. There may be temporal differences in severity from one allergen exposure event to another, possibly due to a genuine change in a patient's clinical status, a change in dose of allergen or the addition of augmentation or cofactors that can exacerbate allergic reactions.16-18 Perceived severity depends on subjective interpretation of symptoms and can also vary depending on what else may be going on in an individual's life (eg, stress at work or home, other chronic disorders, level of risk aversion, and cofactors) and on whether they are a patient or a carer.

We believe it is helpful to consider severity of allergic reactions from the perspective of each of the key stakeholders.

Allergic individuals and their carers: patients and their carers tend to under- or overestimate the potential severity of severe allergic reactions, and they may not seek medical help.19 For example, clinical experience shows that families often consider angioedema in the context of an allergic reaction to be much more significant than mild wheeze; their allergy-experienced physicians are likely to disagree considering wheeze to be more severe (and potentially life-threatening). Patients and their carers may be used to wheezing with viral infections and therefore treat allergen-induced wheezing with their usual asthma treatments not appreciating that, in this context, the bronchospasm and resulting symptoms may worsen rapidly. Any disruption to daily life can be reasonably considered by the family to be a significant or severe event: for example, missing a day of school due to urticaria or visiting the emergency department due to anaphylaxis.

Family doctors rarely encounter allergic reactions and may not have had training, the clinical experience, or sufficient time within the consultation to assess their severity. Epinephrine (adrenaline) may be prescribed when it is not indicated, or a patient may be referred to the emergency department when an allergic reaction is not potentially life-threatening. Conversely, the severity may be underappreciated and the reaction only treated with antihistamines and corticosteroids instead of epinephrine.20

Emergency department physicians and first responders in the community may not appreciate the allergic origin of clinical scenarios that they encounter. The differential diagnosis for anaphylaxis is very broad.21 So, in the absence of any objective point of care diagnostic test, the constellation of symptoms and signs caused by severe multisystem allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) must be recognized if correct emergency treatment is to be initiated.

Allergy specialists are trained to recognize the clinical spectrum of allergic diseases and to pragmatically evaluate their patients’ previous reactions. An accurate evaluation of severity is required to determine emergency treatment and personalize care plans. Most allergists do not see their patients during acute allergic reactions so there is a need to accurately, but retrospectively, assess the potential severity.

Health psychologists need to be able to separate the physiological symptoms of allergic disease from the psychological impact and determine the impact that is due to any psychological comorbidities. Such an analysis has profound implications for correct treatment and management and for alleviating patient/parent anxiety and concerns.

Food industry and public health bodies may consider a severe outcome to be any change in a person's quality of life, unscheduled access to medical care, loss of time at work, school, or studies.

While there are clear differences between the perspectives and needs of these different stakeholders, there is also considerable overlap and this could feed into a harmonized approach. A harmonized severity scoring system for allergic reactions ideally needs to take into account the perceptions and needs of different stakeholders. Grades of severity should be distinct to facilitate their utilization by patients, parents, healthcare professionals, and other relevant groups. Ensuring that these grades make sense to other groups who may use the system will be a challenge, but it is essential for any proposed harmonized system that it is accepted by all stakeholders.

4 WHAT SEVERITY SCORING SYSTEMS ARE CURRENTLY AVAILABLE?

Different scoring systems have been proposed to assess the severity of acute allergic reactions. These address allergic reactions induced by food,6-11 drugs12, 13 Hymenoptera stings,4, 5 and adverse reactions to allergen immunotherapy.14, 15 None of these was intended to be widely applied to all types of acute allergic reaction, despite some having been extended in this way.22-26 Data obtained from both clinical trials6, 7, 10, 14 and emergency room visits or intensive care unit (ICU) admissions4, 5, 12, 22-25 have formed the backbone of reviews, position papers, and consensus reports.9, 26-28 However, these scoring systems classify severity in different grades using ordinal scales that are not equivalent across the different scoring systems. Methods range from valuing key symptoms and signs5-7, 13, 23 to more complex algorithms, for example, including the exposure dosage,10, 22 fulfillment of 2 or more criteria,4, 29 summation of symptoms to assess severity,14, 20 or related to number of organs involved and treatment plan.11 Furthermore, some of the classification systems only cover the most severe allergic reactions (ie, anaphylaxis),5, 15 while others are designed for a wider spectrum of reactions.9, 27, 30

Almost all current scoring systems are organ-specific, dividing symptoms and signs according to origin (ie, the skin, respiratory, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and nervous system), there is less consistency in terms of which symptoms and signs are included. Skin symptoms usually include pruritus, urticaria, angioedema, and flushing/rash. Gastrointestinal features consist mostly of subjective symptoms (eg, oral allergy syndrome, nausea, and abdominal pain), emesis, and diarrhea. Cardiovascular features include change in heart rate (from tachycardia to cardiac arrest) and different grades of hypotension. Neurological features are less consistent, with grades of anxiety and consciousness (from reduced activity level to total loss of consciousness). The biggest discrepancies are found in respiratory symptoms where some only apply airway obstruction,14 while others incorporate different levels of laryngeal symptoms, wheezing, dyspnea, asthma, cyanosis, and respiratory arrest.9 Symptoms from upper airways (ie, nose and eyes) are covered by some9, 25, 28 and excluded by others.4, 12, 23 No approach has included a full set of symptoms and signs and the heterogeneity of scoring of each symptom/sign is pronounced, with classification ranging from “present” to “mild/moderate/severe” to the 6-grade comprehensive Japanese ASCA system31 (not available in English). A more limited number of grades (eg, mild, moderate, and severe or give epinephrine/do not give epinephrine) may be more useful for patients and nonallergy specialists. However, for research purposes, and to inform and validate more simple systems, it may be preferable to have a numerical severity score with more gradations.

Comparison across historical approaches is difficult, but not impossible. Categorical scales would need to be recalculated into comparable numerical values, which would involve difficult decisions about interpretation and categorization of diverse symptoms. This would need to be addressed with caution as comparisons across historical approaches would undoubtedly involve other important differences, such as diverse study populations (community versus hospital), ages (children versus adults), and routes of exposure (food versus Hymenoptera venom). Moreover, these comparisons would need to overcome some vague terms without clear definitions and the fact that none of the severity scoring systems is validated nor were any specifically designed for the proposed comparisons.

5 WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES ASSOCIATED WITH DEVELOPING A SINGLE UNIFIED SEVERITY SCORING SYSTEM FOR ACUTE ALLERGIC REACTIONS?

The key problem in developing an allergic reaction severity score is the lack of a reliable, evidence-based, gold standard criterion standard that can be used as a reference for derivation and validation. This is one of the research needs being addressed by the iFAAM study32 and may provide a better outcome measure to use in generating a severity score. This in itself would need validation across the breadth of clinical allergy. Extending these systems to all allergic reactions is challenging, not least because of possible bias from a nonrepresentative sample, with implications for both reliability and validity. Furthermore, the existing allergy nomenclature is far from being harmonized.33 A better insight into the disease mechanisms underlying different allergic reactions and an endotype-driven approach34 would help to develop a common methodology across the huge spectrum of allergic disease. The range of allergic triggers, clinical presentations, and ages plus the potential geographic diversity creates issues with adequate validation of any scoring system in all the key target populations.

6 A PROPOSED APPROACH TO DEVELOPING A SEVERITY SCORING SYSTEM

An ideal scoring system for the severity of allergic reactions would be based on easily and routinely recorded variables. It should be applicable to all patient populations and to any acute allergic reaction, regardless of the trigger. A classification of severity of acute allergic reactions also should fulfill two underlying premises: (i) as the severity increases, the number of involved organ systems will usually increase and (ii) cardiovascular, neurological, bronchial, and laryngeal involvement are potentially life-threatening and therefore signify more severe reactions. Ideally, a severity scoring system would have two formats to deal with the two different premises that both have different raisons d’être (see above). A continuous numerical system takes into account the totality of the available clinical data and a simpler form with a small number of discrete grades. Scores from the two formats should each be able to be mapped onto each other. Additionally, scores associated with less severe symptoms or signs should be lower than scores associated with more severe ones.

In the simpler format, severity would be classified into different grades. Such an approach would be mainly intended for the more “routine” clinical management of patients, for nonallergy specialists and perhaps patients. It is therefore suggested that only three grades are included as follows: The mildest reactions (grade 1) would include isolated local reactions of the skin or mucosa at the first contact with the allergen; an intermediate grade (grade 2) would include reactions that involve more distant skin, upper airway, and/or gastrointestinal tract; and then, the most severe, potentially life-threatening reactions (grade 3) would comprise cardiovascular, neurological, bronchial, and/or laryngeal involvement (Table 2). This 3-level classification system could, for example, be graphically represented with a 3-color code, yellow-orange-red for grades 1-3 (see Table 2) that would facilitate understanding and wide dissemination in the lay and nonspecialist healthcare communities. It would also facilitate individualized management with patients with different risk profiles advised to use epinephrine at different grades.

| Local reactions | Systemic reactions | |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 |

| Isolated local allergic reactions of the skin or mucosa at the first contact with the allergen. | Allergic reactions that involve skin away from the site of allergen contact, upper airway, and/or gastrointestinal tract. | Severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reactions involving cardiovascular, neurological, bronchial, and/or laryngeal symptoms and signs. |

In the more nuanced numerical format, the proposed severity scoring system would facilitate the needs of researchers and provide a detailed description of, for example, food challenge outcomes. If the resulting score could be interpreted in relation to the simpler grading system, flexibility would be enhanced making it useful to a wider number of stakeholders. The score would be generated using a list of variables derived by consensus by a multidisciplinary panel of experts. A numerical weighting would be applied to each variable; this weighting could be derived in step 1 by expert consensus (a subjective score) and then in step 2 by utilizing a large database of clinical data from patients experiencing acute allergic reactions (an objective score).

A data-driven approach to generate an objective score must be incorporated as it is more likely to produce a valid model. This lends itself to being integrated into, for example, probabilistic models being developed for allergen risk management by the food industry.35 Such an approach would utilize a statistical system to determine which variables to use and the weighting to be applied to each of them. Constructing an objective score would require data from allergic reactions experienced by a large population of patients who have undergone a comprehensive clinical evaluation including all the clinical manifestations of the reactions and a confirmation of their allergy diagnosis by the criterion standard diagnostic test. The challenge is that the severity of each allergic reaction needs to be quantified to provide an endpoint against which a model can be generated using the available clinical variables. Such a criterion standard measure for severity does not currently exist; the best approximate we have is likely to be a consensus severity assessment made by a large multidisciplinary group of experts.

Patients would be assigned to a grade according to their most severe symptom/sign, for example, grade 2 may include symptoms of grade 1 and grade 2. These grades would be generated using the approach described in the text. Grades would have the ability to be easily translated into clinical management, although individual patient characteristics and circumstances need to be taken into account so that different patients might be instructed to use epinephrine at different grades according to their risk profile.

7 HOW SHOULD WE VALIDATE A NEW HARMONIZED SEVERITY SCORING SYSTEM?

A new severity scoring system would need to be validated to ensure that it provided an accurate assessment of severity in different populations at different time points. There are a number of accepted steps in this process.

Face validity: Face validation of an acute allergic reaction severity score is a key step as it assesses whether the intended users are satisfied with and understand the system. Some preliminary work would be required to make a case that the existing multiple systems should be replaced by one harmonized system. It must be made very clear what the new measurement means in terms of benefits for the diverse stakeholders and what type of data and results the tool can—and cannot—provide. For example, an international panel of diverse stakeholders could be asked to review the score to assess whether or not they feel that it is appropriate for their needs. Some refinement will probably be required to ensure that the approach is optimized for use in different clinical setting.

External validation The refined new severity scoring system would ideally then need to be validated statistically using external data. Given the aim of developing one harmonized score, this would require extensive research and cover a number of different areas, such as assessing it against the use of epinephrine and high dependency care admission. This likely to prove challenging as both epinephrine use and admission vary between healthcare systems and physicians. Criteria for validity would need to be set in advance.

Cross-sectional validity would focus on the ability of the scoring system to differentiate between those experiencing outcomes of varying severities and also in comparing predicted with actual observed outcomes using standard parameters developed to assess the validity of models. An ideal score would need to function in different health settings worldwide, with different triggers, dosages, and threshold values and in different age groups and languages.

Longitudinal validity is also important. For example, patients who have been treated with an effective immunomodulation therapy might expect to have less severe reactions after treatment although this might be complicated if their threshold/eliciting dose also changes.2 In this respect, the minimal clinically important difference (MCID; ie, smallest difference in the score associated with the severity of acute allergic reactions that can be differentiated by an expert allergist) needs to be calculated to assess the resolution of the scoring tool. For clinicians and researchers alike, it is critical that the MCID score is a valid and stable measure. A low MCID value may result in overestimating the positive effects of treatment, whereas a high MCID value may incorrectly classify patients as failing to respond to treatment when in fact the treatment was beneficial.

This validation work would require a large number of clinical databases where the scoring system could be assessed against the best available assessment of severity. Many such datasets already exist. Examples are anaphylaxis registers including the UK registry,36 central European NORA registry,37 and the North American FAAN registry38: Hospital admission data would be available from the UK Imperial PICAnet39 and the Malaga database.40 All of these databases would need to be carefully assessed in terms of their strengths and limitations, with a combination of datasets providing the best option.

8 IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Following derivation and external validation, it is critical to assess whether the new scoring system is used as intended and translates into improved clinical outcomes (eg, improved decision-making in reactions, reduced risk, and better quality of life). It is also important to ensure that it does not result in important unintended consequences. This is ideally assessed using a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which the new scoring system is compared with usual care; depending on the likely risk of contamination between intervention and control arms, a cluster design may be needed with different trial sites randomized to different arms.41 If a formal experimental design is not possible, a quasi-experimental design could be employed (eg, an interrupted time series or a controlled before-after design) although it should be noted that these alternative approaches are inherently at increased risk of bias when compared to a RCT.

9 IMPLEMENTATION

Implementation requires local, national, and international champions to facilitate the adoption of a new approach so that it becomes embedded in routine care, together with case studies to demonstrate its utility and value to various different stakeholders. This can be promoted with the incorporation of the tool into guidelines or other coding systems and related efforts to promote diffusion and adoption.42, 43 Education of healthcare professionals and other community professional groups such as teachers is essential, as well as risk assessors and managers in public health authorities and the food, hospitality, and catering industries alike. Information technology can also be utilized to promote a new approach by developing, for example, a decision support engine44 that stakeholders can use. Finally, demonstrating that a severity scoring system improved clinical outcomes (eg, better quality of life; reduced risk; and improved decision-making in reactions) on a population-based level would promote the further take-up of the approach.

10 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The accurate assessment and communication of potential severity of acute allergic reactions are important to patients, clinicians, researchers, food industry, and public health authorities. Many severity scoring systems are available, usually within the context of one group of allergens sources. However, none of the scoring systems has been developed using the gold standard method for the development of measurement and/or prognostic tools. Furthermore, none of these scoring systems has been validated. A validated reaction severity scoring system is needed to standardize patient monitoring. We propose an approach to developing a harmonized scoring system for acute allergic reactions that are based on a data-driven method, informed by clinical and patient experience as well as by the perspectives of other stakeholders. We envisage two levels of details: an ordinal three-grade-based format and a continuous scoring system giving a continuum from mild to severe reactions that are clinically meaningful. This would allow the same system to be used by patients, clinicians, researchers, the food industry, and public health regulators. The new approach would need to be tested for reliability and validity using gold standard methods in a range of settings and populations. We propose that common epidemiological, clinical observational, and clinical interventional datasets should be collected to promote future collaboration, cross-validation, and refinement of the severity scoring system. For a harmonized system to be successful, an implementation strategy would be required and its impact would need to be assessed. Finally, severity should be considered as just one of a range of important aspects of risk assessment and risk management of allergic diseases. To determine the optimal management of a reaction for a patient, assessed severity needs to be integrated with the clinical context, for example, the dose of allergen, route of contact, rapidity of onset, and other intrinsic (patient-related) and extrinsic factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The task group would like to acknowledge the support from the iFAAM, TRACE, Europrevall, and NORA e. V. Anaphylaxis Registry study teams in developing the proposed approach to developing and validating a severity scoring system. The group would also like to thank Estelle Simons for her review of the initial draft manuscript which has helped up develop this approach. This activity was initiated and supported by the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) as part of the Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Initiative.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no specific conflicts of interest in relationship to this paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The EAACI initiative on the severity of allergic reactions was initiated by Antonella Muraro. It has built on work undertaken by Montserrat Fernandez-Rivas in the iFAAM project led by Clare Mills, work by Andrew Clark in the TRACE project, and work by Margitta Worm in the NORA project. Additionally, it has benefited from Esben Eller's and Carsten Bindslev-Jensen's review of all the existing severity scoring systems. Kirsten Beyer, Victòria Cardona, Jonathan O'B Hourihane, Marek Jutel, and Aziz Sheikh led the drafting of specific sections of the manuscript which Graham Roberts used to develop the initial draft manuscript. All the authors reviewed and contributed to the development of the final paper.