Survivorship Needs and Experiences of Survivors of Head and Neck Cancer in Rural Australia: A Qualitative Study

Poorva Pradhan and Helen Hughes are co first authors.

ABSTRACT

Aim

Head and neck cancer (HNC) survivors experience complex survivorship needs compared to other cancer types. This is exacerbated for people living in regional and remote (rural) areas of Australia, who experience poorer outcomes, higher physical and psychological needs, and poorer quality of life compared to their metropolitan counterparts. Little is known about the general survivorship experiences of rural HNC survivors in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. This study aims to explore the general survivorship experiences of people living with HNC in rural areas of NSW, Australia.

Methods

HNC survivors living in rural NSW were recruited, and semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore their general survivorship experiences. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using a qualitative thematic analysis approach until saturation of themes was reached.

Results

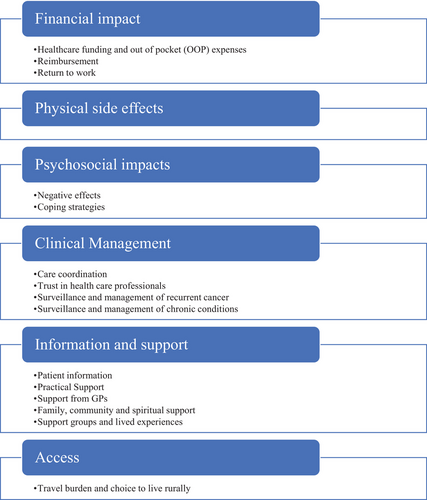

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 participants, with a mean age of 65 years. The most common diagnoses were oral cavity (41%) and oropharyngeal cancers (29%). Six key themes emerged around general survivorship experiences among participants: 1) financial impacts, 2) physical effects, 3) psychosocial effects, 4) clinical management, 5) information and support needs, and 6) access.

Conclusions

Rural cancer survivors face unique survivorship concerns, exacerbated by living further from specialist care. The unmet needs of people living in rural areas include financial reimbursement, psychosocial services and support, and access to survivorship care closer to home. Understanding cancer survivors' experiences throughout the care journey can identify unmet needs. By recognizing these needs, they can be more readily addressed by government policy and other interventions.

1 Introduction

Advancements in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment have increased patient need, and demand for, high-quality survivorship care [1]. Survivorship encompasses the multitude of experiences of life-long care after cancer diagnosis, including physical, psychosocial, and economic issues [2, 3]. In Australia in 2022, 5189 people were diagnosed with head and neck cancer (HNC) [4]. With increasing survival rates for HNC, there are now more than 17,000 people potentially living with the long-term side effects of treatment in the community [4, 5].

HNC survivorship experiences are complex due to the interplay of physical and psychosocial impacts of cancer and its treatment. The complex anatomy and functions of the head and neck, coupled with intensive treatments (including surgery, radiotherapy, and/or systemic therapy), can result in side effects such as disfigurement, difficulties with eating, swallowing, speaking, and breathing, chronic lymphedema, and chronic pain [6-11]. As a result of this and compared to other cancer survivors, HNC survivors are at higher risk of psychosocial and physical impacts of the cancer, [12], with psychological distress driven by long-term physical side effects [8, 13, 14]. A multidimensional and multidisciplinary approach to HNC survivorship care is needed to support HNC survivors [15-17].

Issues of access further complicate experiences for HNC survivors living in regional and remote (hereafter rural) areas. Individuals with cancer living rurally generally experience poorer outcomes, higher physical and psychological needs, and poorer quality of life than their metropolitan counterparts, suggesting potential differences in survivorship care [18]. In Australia, research has investigated the impact of geography on healthcare outcomes among individuals with HNC in Queensland, Australia [19, 20]. Foley and colleagues' [17] findings underscored disparities concerning the accessibility and utilization of healthcare services, leading to heightened unmet needs and elevated stress levels for rural residents. Such early studies have highlighted that numerous survivorship challenges exist for people from rural areas, such as issues of stress, disparities in treatment timing, the effects of limited family support, challenges in accessing care during recovery, and financial and employment concerns. Initially focusing on access to speech pathology care, these studies based in Queensland later expanded to explore more general issues of HNC survivorship but were not initially designed with this focus. Further, in one mixed-methods study, though interviews were conducted, these were not in-depth interviews and did not include the perspectives of long-term survivors. Lastly, the studies from Queensland drew direct comparisons between urban and rural populations. While important, further, more detailed explorations of the general survivorship experiences of rural survivors of HNC are required. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the survivorship experiences and needs of HNC survivors living in rural areas of NSW with a qualitative methodology.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Scope of this Paper

The intent of this investigation was to explore the general survivorship experiences of people with HNC living in rural areas, without comparisons between rural and urban patient experiences. This study was conducted wholly in New South Wales (NSW), the most populous state in Australia, rural residents making up approximately 30% of the state's population [21].

2.2 Recruitment and Sampling

Participants were recruited via prior involvement in a larger cross-sectional survey. All potentially eligible participants were sent a written questionnaire on survivorship issues and were asked to indicate their interest in participating in interviews. For this study, we have considered the survivorship period following 12 months post-diagnosis of HNC consistent with Margalit et al. [22]. Therefore, we also recruited patients following the completion of active treatment. Similarly, we have identified short-term survivors (1–5 years posttreatment) or long-term survivors (>5 years posttreatment) as per Garcia-Vivar and colleague's. [23]

Consenting participants were then purposively sampled to achieve a balance of gender, age, diagnosis, and location where practicable. Participants were eligible if they were aged 18 years and older, lived in rural areas of NSW, and had been diagnosed with HNC (excluding cutaneous and thyroid cancers) in the past 15 years. Participants were ineligible if they had any cognitive impairment that may have interfered with their ability to participate. We adopted the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) to ascertain the “remoteness, which is based on the Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia” (ARIA +, ABS Remoteness structure) [24]. ARIA+ is a leading indicator of remoteness in Australia, with classifications ranging from major cities (0; high accessibility) to very remote Australia (15; high remoteness). It is derived from road distance from various populated locations. For example, under this structure, a patient residing in Port Macquarie (390 km away from metropolitan Sydney) was considered as “Inner Regional” [24].

Participants were recruited from four HNC treatment centers in NSW, one located in metropolitan NSW (Chris O'Brien Lifehouse, Sydney) and three located in regional NSW (Mid North Coast Cancer Institute, Port Macquarie; Northern NSW Cancer Institute, Lismore; and the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District). Ethical approval was granted by the Sydney Local Health District Human Ethics Committee (RPA Zone; Protocol No. X23-0027 & 2023/ETH00135). All treatment centers in the study are public facilities providing tertiary healthcare services. However, Chris O'Brien also offers private healthcare services. In Australia, residents have access to free universal healthcare through the public healthcare system, known as Medicare. However, individuals also have the option to choose private healthcare services, which may involve additional costs.

2.3 Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with consenting participants by P. P. and R. V. between July 18, 2023, and September 14, 2023. The interviewers were guided by an interview outline developed by the study team. Due to the geographical distance of participants from the interview team, interviews were conducted either by phone call or videoconference, depending on participant preference. One participant was accompanied by a carer who provided support answering questions due to the participant's speech impairment caused by a total laryngectomy. Interviewees were not known to the interviewers prior to participating, and no repeat interviews were conducted. All interviews were audio recorded, then transcribed using the transcription software “Otter AI” [25], and the accuracy of the transcriptions was reviewed and confirmed by P. P.

2.4 Analysis

The interviews were analyzed thematically in an inductive manner by using a qualitative descriptive approach as described by Coates et al. [26]. This approach was adopted so that the themes emerged from the data rather than existing theory. The Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework [27] was used to create the interview guide. Coders (R. V., P. P., and H. H.) undertook individual preliminary coding of the first three interviews before discussing the initial findings. Transcripts were read several times, and the excerpts from transcripts were coded into meaningful codes. Through discussion, codes and sub-codes were identified, which were then used to create a coding tree. The remaining transcripts were analyzed according to this coding framework.

Subsequent analysis (formal coding) of all the interviews was undertaken by H. H. and P. P. using NVivo qualitative analysis software [28], with R. V. quality checking all interviews. New codes, sub-codes, and renaming codes were only done following discussion with, and agreement from, all researchers. Analysis was conducted in parallel with interviews, which informed the themes explored in subsequent interviews, in order to reach saturation in all emergent themes. Interviews were conducted until saturation of themes was achieved (at the 15th interview), after which two additional interviews were conducted to confirm data saturation. A total of 17 interviews were conducted.

3 Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

In total, 619 patients were invited to complete surveys assessing health care utilization and unmet needs (Pradhan et al., accepted manuscript in press), of which 112 agreed to participate in the cross-sectional survey. Of these, 58 indicated their interest in being interviewed. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 participants. The mean age of participants was 65 years, with males comprising 59% (n = 10). Most (94%, n = 16) participants lived in inner regional areas; 41% of participants were short-term survivors, and 59% were long-term survivors. The interviews varied in length from 26 to 90 min. Participant demographics are outlined in Table 1.

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean age | 65.1 years |

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 (59%) |

| Female | 7 (41%) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed (full time/part time) | 7 (41%) |

| Self employed | 3 (18%) |

| Retired | 7 (41%) |

| Geographical location | |

| Inner Regional | 16 (94%) |

| Outer Regional | 1 (6%) |

| Time since diagnosis | |

| Short-term survivors (1–5 years) | 7 (41%) |

| Long-term survivors (> 5 years) | 10 (59%) |

| Tumor location | |

| Oral cavity | 7 (41%) |

| Oropharynx | 5 (29%) |

| Larynx | 2 (12%) |

| Parotid | 2 (12%) |

| Nasal | 1 (6%) |

| Treatment history | |

| Surgery | 7 (41%) |

| Radiation therapy | 1 (6%) |

| Surgery + radiation/chemotherapy | 4 (24%) |

| Radiation + chemotherapy | 5 (29%) |

| Tumor staging | |

| Local/regional | 11 (65%) |

| Distant metastases | 4 (23%) |

| Not known | 2 (12%) |

3.2 Findings

Six major themes emerged from the interviews (Figure 1), and exemplar quotations supporting each of the themes are available in Table 2. The rural participants in this study described their general experiences of survivorship after HNC, and therefore the findings are described through this lens. Where applicable and directed by the content of the interviews, specific experiences of being “rural patients” are highlighted in the results.

|

Themes Sub-themes |

Quotation |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Financial impact | |

| Publicly funded vs. privately insured care |

“We have private medical, but we still had to pay some amount. I can't remember what it was now. Because it's too long ago. But we did have to pay some.” [Female, 60 years] “I stopped telling people I had private health insurance. My experience in the public health system was every bit as good as what I was receiving the private hospital, in some ways it was actually better.” [Male, 66 years] “We did discuss doing some radio-labelled iodine, proton, magnetic resonance, whatever. But I would have had to pay for that. No, it wasn't cheap. It wasn't on Medicare.” [Male, 45 years] |

| Out of pocket (OOP) costs |

“The main costs throughout that process [were] the dental care because we didn't have any dental [cover]. … So that was expensive.” [Male, 78 years] “I was a little bit worried at the time. Because we had to come up with some money that we didn't probably have. … We had children and mortgages and stuff like that … We had to take money out of savings.” [Female, 60 years] |

| Reimbursement |

“But it's still only a percentage [of what it costs]. It's not a full amount … finances are a big thing, you know, the government don't help you out to a substantial amount”. [Female, 56 years] “The [IPTAAS paperwork] got lost. So that was a bit crappy. And this counsellor then just went, ‘You know what? This is too hard. Let's just go with the Cancer Council.’” [Male, 67 years] “I realized [later] there was a lot more [financial support services] out there … I found that they didn't tell a lot of people, that people didn't know of it.” [Female, 60 years] |

| Return to work |

“I was really embarrassed about the way that I looked. … I had popped in to see some of my work colleagues … one of my friends walked past me didn't even recognize me” [Female, 49 years] “Yeah, you know, that they're gonna have less outpatient services for physiotherapy and occupational therapy and all these things. Okay. So, I don't think things are going to get any more available locally” [Male, 45 years] |

| Theme 2: Physical side effects |

“I had trouble understanding things, comprehending what was going on a little bit … I scraped the car against that gravel truck”. [Male, 78 years] “We used to go out to restaurants and things. For lunch and dinner. But now, we don't really [go] that much … so it's very frustrating.” [Male, 66] |

| Theme 3: Psychosocial impacts | |

| Negative effects |

“I'm not claustrophobic, but it was a real challenge … the second day when I went in one of the nurses [was] saying. ‘Hey, how'd you go? How are you feeling?’ And I just burst into tears.” [Female, 49 years]. “You can't drink, you can't eat. And I remember sitting on the couch crying. I couldn't have read the book; I couldn't concentrate. So there was this one escape—like reading and I couldn't concentrate. … And I was in just so much pain. And it's got to get better, but you don't know how quickly. [You think] it'll just get worse and worse.” [Male, 62 years] “It affects my eating in a lot of ways, of what I eat. So I'm quite embarrassed in meeting people and going out for a coffee. … I didn't like meeting people.” [Female, 56 years] “My anxieties went through the roof. As far as you get very anxious because my speech and my vocabulary had changed.” [Female, 56 years] “People say oh, I've just been to a funeral, and they've got two little kids and how sad it is. And I just, I just burst into tears, … because I've survived. And they are young.” [Female, 60 years] “I try very hard not to live in any fear of [the cancer] coming back. But of course, everything that happens in my body now I immediately go straight to Oh, my God, you know, is this cancer?” [Female, 65 years] “When the [cancer diagnosis] anniversary comes around like now, I become quite nervous … the people in the office, I'm sure they notice the week leading into any of my appointments.” [Female, 60 years] “But as I said, you know, I stayed in [for radiotherapy in metropolitan city]. I think it was nine or 10 weeks…. Yeah. But being away from my family was hard.” [Female, 56 years]. |

| Coping strategies |

“[Participant's] pretty level-headed and can deal with a lot of any issues that he has … yeah, he was just determined to live and that he was going to beat the cancer. He was going to survive because he wanted to live.” [Female Caregiver] “The way I coped with things is I went straight back to work. It kept my mind occupied on something else other than cancer.” [Female, 56 years] |

| Theme 4: Clinical management | |

| Care coordination |

“So it's not just a matter of understanding that we're going to have surgery to have reconstruction, that's also the chemo, the radiation, the ongoing appointments backwards and forwards from my hometown back to Sydney over time.” [Female, 56 years] “They had a nurse over there, who was in charge of patient liaison and stuff. And she was really good”. [Male, 62 years] “And the doctors and everyone else involved there make it easier to travel by grouping appointments, to give you a chance to drive down”. [Male, 79 years] “It was quite incredible. They [treating team] talk to each other, they knew each other”. [Male, 67 years] “Sometimes it was a bit tricky because [the surgeon] is in private suites. Although I see him as a public patient and when I had my MRIs they weren't sending them on to [the surgeon]. So [the radiation oncologist] was getting them and thought that [the ENT surgeon] was as well. But we fixed that.” [Female, 49 years] |

| Trust in health professionals |

“I fully trusted what [the radiation oncologist] has to say, you know, he's a young, sort of young specialist, and I believe he really wants to be the best at what he does.” [Male, 67 years] “I strongly feel the need of health care professionals [locally trained GP] understanding the culture here and the community here.” [Male, 45 years] “At the moment it's the longest in between appointments that I've had. So that's a good thing because I [haven't] had cancer.” [Male, 67 years] “I think full body scan would be good to be able to have. And I know they're quite expensive. And not everybody can go.” [Female, 60 years] |

| Surveillance and management of recurrent cancer | “So, it will be a PET scan. Yeah. And the gallium, PET scan. I have those just I've got to have all the bloods done. Although I'll be on the sixth of September, and I'll be up in [metropolitan city] for the three days”. (Female, 77 years). |

| Surveillance and management of chronic conditions | “I've got to see the GP to get the medication… and we do a blood test at that point to check out how the diabetes is going.” [Male, 76 years] |

| Theme 5: Information and support | |

| Patient information |

“You're traumatized, well I was. I'm hearing what people are saying and it's not until you sit back and reflect that you think ‘I didn't understand that”. [Male, 67 years] “I had kept a diary when I was in hospital, and then I'd ask him [treating doctor] questions.” [Male, 72 years] “I got down to the point of saying, ‘So how shit is it going to be’? They [the doctors] won't say. And so the nurses would tell you a little bit more than the doctor I would see.” [Male, 67 years] “I didn't really get too much information from the head and neck clinic team. But I probably didn't really blatantly straight out ask the question.” [Male, 67 years] “Each one came as a bit of a surprise, particularly the PEG tube that was not outlined from the outset … a simple fact sheet could have done it easily.” [Male, 66 years] “If radiotherapy is given to anyone in the throat area, they should be told that it'll create scar tissue that may shrink and restrict their ability to swallow properly. And to have an esophagus dilation procedure if available. No one told me that.” [Male, 79 years] |

| Practical support |

“I wasn't allowed to drive myself to and from [treatment], so I had to have someone come and live with me. Each week, I had someone else, whether it be a sister or friend to come and live with me; they would have to drive me in and be with me during the process, and then bring me home.” [Female, 65 years]. “I would have appreciated another avenue to having to make phone calls for meals and things. I didn't eat because I couldn't talk, you know.” [Female, 77 years] “I guess [the patient] relied on me a quite lot because I'm a retired nurse. And so I knew more about the process. And he relied on me as I helped him kind of understand medical side of things. But it meant he didn't have to kind of question as much himself either. Or remember things. That, you know, he'd been told because he had me as a backup. We used to diary a lot to write the medications.” (Male, 78 years). |

| Support from GPs | “And I've had my GP overall probably about for 30 years … so I have a good relationship. With him knowing me and I know him.” [Female, 56 years] |

| Family, community, and spiritual support |

“I didn't see anybody at the hospital at all, from a religious point of view. Normally the priests or the Ministers get around if they got time to see the patients that are in need of them and spiritual support. Which feels important to a lot of people, myself included.” Female, 77 years] “I felt quite supported by you know … I had friends and stuff that was supporting me as well. And so I just stay very close to home. And I was lucky that I had people that could, you know, bring stuff to me if I needed it food or whatever.” [Female, 65 years] |

| Support groups and lived experiences |

Informal support: “ Probably. the support I got from people I knew who had been through it previously, was of more value to me than a partner who was in a meltdown.” [Male, 66 years] “Because there's more as a small community and the people that you meet whilst you're waiting for your radiation time slot. Generally, you will come across somebody you know….We would see each other from time to time and we talk about different side effects and I'd go like fingernails for example.”[Female, 60 years] Formal support: “We would see each other from time to time and we talk about different side effects.” [Female, 60 years] “So I went to a couple of the meetings afterward when I was feeling a bit better. And like driving and, you know, it was, it was good to chat with other people who had been on the same journey but only went twice because I really felt that I didn't need it. And it's an hour and a half drive to go to it because it was more so I just.” [Male, 62 years]. “I felt like I didn't belong there [at the support group] either. Because … I had cancer for three weeks, as far as I knew. … and I go and sit in a group of people who were talking about, you know, that may be suffering for years and years. … I think sometimes people … maybe want to do it a bit more privately than share with a large group sometimes, too.” [Female, 49 years] |

| Theme 6: Access |

“[Participant] still has contact with the speech pathologist. If he has any problems with the speech. He just emails her and she's really good.” [Male, 66 years] “We were doing everything kind of over the phone … I wanted him to see me. I wanted him to look at me, like, you know, check my neck, like, feel it because that's what you do. And that's how you know that I'm okay.” [Female, 49 years] “Having that Cancer Institute close to home definitely made it, from my experience, to be much better than it might have been.” [Female, 65 years] “I just wanted to talk to someone about [the treatment], and there's no one to talk to. So, you should talk to your GP about it, but he doesn't really know because that's not what he does.” [Male, 62 years] “I'm not sure that services or access to them is going to improve anytime ever for people with head and neck cancer, because he only saw two people in his whole career.” [Male, 45 years] “The biggest sign of emotional stress was after the treatment finished. Because when I was in [Regional town] all the specialists were there, and I lived right next to the hospital. But when I came home suddenly, I'm 150 kilometers away … my treatment's finished and they've moved on to other patients. So I can't just phone them, you have to get to accident and emergency at the [local] hospital.” [Male, 62 years] “I'm not sure how much of its [psychological support] available because I've never had to use it or been offered it either”. [Female, 60 years] |

| Travel burden and choice to live rurally |

The only difficult thing was that it was very painful … our roads are not very good and now full of potholes because they've been a lot of rain. And every time we hit a pothole It was very painful for me … “it was quite a stressful journey each way.” [Male, 78 years] “Living in a regional area I've travelled to Sydney [for care]. But that's the price you pay. And you're very well aware of it when you do move to regional areas. So you make allowances.” [Male, 76 years] “And so, I think there should be whether it's specialists closer to home that you can go and see and communicate, making less visits to [specialist cancer center in metropolitan city] there.” [Female, 56 years]. |

3.3 Theme 1: Financial Impact

All participants discussed the financial impact of treatment. Experiences relating to costs varied depending on prior employment, geographic distance to services, and existing financial situation.

3.3.1 Healthcare Funding and Out-of-Pocket (OOP) Expenses

A total of 15 participants provided information as to whether they accessed publicly funded care (Medicare) or accessed care through private health insurance (seven private, six public, and two a mix). Regardless of access pathway, most participants contributed financially towards some of their treatment and experienced OOP costs, for example, by paying gap fees for consultations with specialists or electing to undergo robotic surgery. In retrospect, however, most participants did not consider this cost to be a burden. However, one participant felt that having private health insurance was a disadvantage because they still had to pay upfront costs associated with their treatment rather than having all their treatment costs covered. As a result, they later switched to receiving care as a public patient under Medicare. For others, lack of private health insurance meant forgoing some treatments due to cost if they were not available on Medicare. For instance, according to one participant, radio-labeled iodine was not available on Medicare at the time of their treatment. Eleven participants discussed OOP costs relating to their treatments; most commonly these were travel and accommodation costs and medical expenses. Two participants highlighted the burden of costs associated with necessary cancer-associated dental care due to them lacking private dental cover, compounded by a lack of public funding for dental care under Medicare. The lack of paid sick leave for two participants who did not work or were self-employed during treatment meant they had to use their savings to cover costs. Three participants owned small businesses in rural areas, such as farms, which they had to temporarily close for a few months to undergo treatment and manage the side effects that followed. One participant, who was employed, spoke about the concern they had around OOP costs and the flow-on effect to other expenses such as mortgages and the cost of raising a family.

3.4 Reimbursement

To reduce OOP costs for travel and accommodation, some participants sought support from government and charity organizations, most commonly the NSW Isolated Patients Travel and Accommodation Assistance Scheme (IPTAAS). However, several participants noted that the proportion of expenses covered by IPTAAS was insufficient. Two participants reported receiving monetary support for transport and accommodation from the Cancer Council NSW, with one participant choosing this pathway over IPTAAS as the process was simpler. Importantly, despite financial reimbursement services being available, not all participants were aware of eligibility or how to access the schemes.

3.5 Return to Work

Five participants reported difficulties returning to work after treatment. Reasons varied from termination of contracts, difficulties performing physical tasks, anxiety due to speech changes and fatigue. One patient, for example, due to excessive pain, was not able to return to work and was receiving government disabled benefits. The participant further pointed out that the pain management services are not equipped in his area (in outer regional NSW), and as a result, he had to work casually on minimum wages.

3.6 Theme 2: Physical Side Effects

All participants mentioned short- and long-term side effects of treatment that they experienced. Commonly reported short-term effects included difficulty eating, radiation dermatitis, difficulty speaking and being understood, weight loss, both chemotherapy- and surgery-induced lethargy, pain, and chemotherapy-induced brain fog and peripheral neuropathy. These short-term effects impacted participants’ activities, for instance, being reluctant to socialize due to changing appearance, and one participant reported that brain fog had led to a minor car accident.

Long-term physical effects reported by participants included difficulty eating due to a variety of causes (lack of taste, difficulty chewing, and/or swallowing), difficulty speaking and being understood (as a result of tracheostomy, other surgeries, or nerve damage), permanent nerve injury (from surgery or radiation), bone necrosis (resulting from radiation), and hypothyroidism. Long-term skin conditions, including psoriasis and skin sensitivity, were also reported. Participants frequently reflected on the impact that difficulties eating and being understood had on their day-to-day life, subsequent psychosocial issues, and consequential resulting behavior change. Less common long-term effects reported included vitiligo, and foreign accent syndrome, and permanent hearing loss.

3.7 Theme 3: Psychosocial Impacts

3.7.1 Negative Effects

The negative psychosocial impact of cancer was widely reported by participants (n = 13), including emotional distress caused by treatment and side effects, as well as long-term fears of cancer recurrence and survivor guilt. Two participants reported emotional distress linked directly to radiotherapy, such as claustrophobia in the linear accelerator, while others linked distress to the short-term side effects of treatment, including brain fog, difficulty eating, and being understood. Many participants reported the toll that side effects of treatment took on their psychological well-being, including difficulty eating, embarrassment about appearance due to radiation skin reactions on the face, anxiety in socializing, and survivor guilt. Ten participants reported being affected by fear of cancer recurrence. They reported little impact on day-to-day life but frequently acknowledged that the fear lingers and the attribution of new, unrelated symptoms to cancer recurrence. Participants often found this fear spiked around their cancer “anniversary” or in follow-up appointments during surveillance.

Unique to the experience of being a rural dweller, participants frequently highlighted the significant negative psychological impact of having to travel long distances to receive treatment without the presence of their families. This experience not only imposed a physical burden but also took a considerable emotional toll. The separation from their family support networks during such challenging times exacerbated feelings of isolation and loneliness.

3.7.2 Coping Strategies

The cohort demonstrated a great deal of resilience through their survivorship journeys, with many (n = 11) not wanting to dwell on the negative, but to use goal setting and keeping busy as a distraction to get through the cancer treatment and follow-up.

3.8 Theme 4: Clinical Management

3.8.1 Care Coordination

Participants reported that disparate elements of their care were coordinated well and that they highly valued this, particularly as rural patients. The need for care coordination may be more acutely felt by rural people than by their metropolitan counterparts, with most participants living several hours away from treatment and follow-up care. Participants liked having multiple appointments on the same day due to the long distances to travel to the cancer center. Conversely, those who reported a negative or neutral experience through their treatment cited a lack of coordination between appointments and aspects of care. The administrative role of the clinician (often nursing and/or support staff) in booking appointments, who acknowledged the unique needs of rural patients, was also praised. Information sharing between the treatment team was identified as critical to effective care coordination, highlighted by the detrimental effects when information was not shared.

3.9 Trust in Healthcare Professionals

Many participants reflected on the close relationship they had with, and trust in, individual clinicians in the acute care space as well as the general practitioner (GP). Trust of treating clinicians was deemed very important to the patient, particularly the lead treating physician (either radiation oncologist or surgeon) and nursing staff. For one participant, who had negative experiences following surgery and a lack of information post-operatively, they felt as though the trust had been eroded. Participants’ GPs were also recognized and cited as trusted members of the care team. Their care was specifically mentioned positively by six participants, as they played a critical role in survivorship, often managing multiple chronic conditions as well as cancer. Reasons for trust in their GPs included their diligence, the long-term relationship between patient and practitioner, and established rapport. One participant reflected that rural HNC survivors need trust in local health professionals, who live locally and understand the needs of the community.

3.10 Surveillance and Management of Recurrent Cancer

Surveillance and management of recurrence were described as critical component of survivorship care. Most participants mentioned surveillance in their survivorship care, either specialist-led (nine participants) or GP-led (four participants). For those in active surveillance, the frequency of appointments was decreasing, which was considered reassuring as they emerged from the immediate posttreatment phase. Most participants were monitored with MRI, PET scans, or physical examination. Some participants who were undergoing surveillance scans, such as gallium scans, had to travel to metropolitan areas for these specialized services; however, many were able to have follow-up scans locally, reducing the burden of travel. One participant expressed a preference for a whole-body scan to help relieve fear of cancer recurrence, but it was too expensive.

3.11 Surveillance and Management of Chronic Conditions

A total of 13 patients discussed the surveillance and management of their chronic comorbidities, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cholesterol management, testosterone deficiency, hypothyroidism, mental health, and pain. Most participants had their chronic diseases managed by their GP, with some conditions managed by dentists, cancer specialists, prosthodontists, physiotherapists, psychiatrists, and counselors. Some participants traveled a few hundred kilometers to access specialized services such as seeing a maxillofacial surgeon for chronic dental management and speech pathologists, highlighting again the burden of travel for people in rural areas. Participants observed these visits as routine, with management occurring opportunistically when presenting to the GP.

3.12 Theme 5: Information and Support

3.12.1 Patient Information

Participants frequently discussed the information they received during survivorship care, as well as their information needs. Most felt that they had been provided with sufficient, well-explained information about diagnosis and treatment (verbal and/or written) from their treating physician. Six participants mentioned they received written information (either formal booklets or handwritten diagrams from their clinician). Written information that could be read later was found useful when participants felt overwhelmed during their initial consultations, and it emerged that at times person-centered information during treatment was more available from nurses compared to oncologists. Three participants described themselves as actively seeking information from their treating clinician during and after treatment. In contrast, others felt they didn't get enough information because they didn't ask the right questions.

Participants who reported more ongoing and serious side effects from treatment (e.g., tracheostomy, nerve damage) described a need for more detailed, treatment-specific information and that they felt unprepared before some aspects of treatment. One participant highlighted the need for more information to support people having radiation for throat cancer, including recipes for texture-modified diets and easy, nutritious meals to prepare, and more information about the types of procedures that will follow in the acute survivorship period.

3.13 Practical Support

Participants received practical support, including transport, accommodation, and some medical support (e.g., wound dressings) from partners, family, and friends. Accommodation near treatment was also provided by charities in some cases, which was helpful for rural patients and their caregivers needing to travel long distances. Medical support posttreatment was provided by partners and family members; however, this was only reported when the partner/family member had medical training (n = 2), so it may not be a finding that is universally applicable to other survivors of HNC or those in rural areas. This was done to assist participants who had difficulty accessing timely care by leveraging relationships and advocating for them. This helped patients navigate the healthcare system more easily. Unmet supportive care needs identified by participants included accommodation for their partner during hospital admissions and transport, as well as support while in the hospital making calls and ordering meals, which was exacerbated by difficulty speaking as a result of their treatment. This lack of support system for patients and the challenges of navigating unfamiliar environments can exacerbate the already stressful experience of undergoing treatment, particularly for rural patients who may not have a caregiver traveling with them for treatment.

3.14 Support From GPs

GPs were a source of information and support for six participants, with most facilitating care plans, one supporting the participant accessing travel reimbursement, and others providing information about services. However, the remaining participants indicated that they primarily saw specialists for follow-up cancer care and expressed satisfaction with the care they received. This minimized their need to consult with their GP regarding cancer-related issues. Some participants also mentioned that while GPs were valuable sources of general health information and support, they may not have the specialized knowledge or resources to address the complexities of HNC treatment and survivorship.

3.15 Family, Community, and Spiritual Support

Family, community, and spiritual support benefited participants psychologically during and after treatment. Spiritual support while undergoing treatment (for instance, the availability of a minister or informal visits from spiritual leaders) had positive effects for participants. However, one participant stated that formal spiritual support wasn't made available to them, despite their desire for it. Overall, for these rural participants, the benefit of staying close to home due to the availability of community, family, and spiritual support was acutely felt by many participants. Traveling away from home for treatment was a common difficulty for rural HNC patients, largely due to the distance from community support.

3.16 Support Groups and Lived Experiences

Eight participants spoke about the formal and informal support they received from other HNC cancer survivors, which provided opportunities to share common experiences. Opportunistic support was often found while in the waiting room for appointments at a regional sub-specialist cancer center or through GPs connecting patients with similar diagnoses. Participants reflected on the value of similar or prior experience of other survivors in helping them on their journey. Two participants said that they would have liked to join a formal support group; however, there was an absence of local support groups closer to home. However, one other participant, who had joined a local support group, found the attendees’ differing experiences challenging and preferred more private meetings.

3.17 Theme 6: Access

Most participants felt supported through treatment and beyond by their care team and that they could easily contact their clinicians via email or phone whenever they needed. While videoconferencing appointments were identified as a need during follow-up and surveillance by some participants, for another participant who had telehealth surveillance appointments during the NSW COVID-19 lockdowns, telehealth did not adequately address their concerns about recurrence.

Participants who lived close to a major rural cancer center valued this proximity and the specialist care they received (n = 4). Some highlighted a lack of specialist cancer knowledge amongst local health care professionals, including GPs, psychologists and/or counselors, and hospital emergency services, which resulted in a care gap for those individuals. Participants felt that the rarity of their cancer and lack of clinician training in the management of HNC and its effects contributed to this gap. As a result, participants (n = 4) said that they would rather travel further distances for better care than stay close to home if they felt the care was inferior. For instance, one participant pointed out that he travels to a metropolitan cancer center for follow-up cancer treatment, as his GP is not experienced in this area. Participants identified the care gap following discharge from intensive specialist care as a major stressor.

Participants overwhelmingly identified that, in retrospect, they would have benefited from access to a psychologist or counselor who understood what they were going through, but that it wasn't made available to them. Some participants felt that it would have been available to them had they asked, but nor was this service offered to them. One participant also highlighted that they felt they would have benefited from receiving care from a dietitian while undergoing treatment in a metropolitan cancer center, but it had not been offered.

3.18 Travel Burden and Choice to Live Rurally

The burden of traveling, in many cases over an hour and a half to specialist care, was discussed by many participants. This distance highlighted the need for accommodation close to the treatment center (for both the individual and a carer), excess burden on family members who provided transport, and a lack of visitors during treatment. Several rural participants who received care in a metropolitan center noted this difference in support, observing that compared to metropolitan counterparts receiving care at the same time who may live closer to specialist care, they had fewer visitors. Beyond travel time, physical effects of the long drive were a stressor for participants. For example, one participant commented on the quality of roads and the resulting discomfort (pain) from a fresh PEG tube wound when traveling on these roads. Despite the burden, participants (n = 4) expressed an acceptance towards this level of travel, in alignment with their choice to live rurally, and acceptance that distance to care was “part of the deal.” On the other hand, a few participants expressed a desire to stay close to home if local care was available and on par with specialist metropolitan centers (n = 3).

4 Discussion

Six key themes emerged about general survivorship experiences among survivors of HNC in rural NSW: 1) financial impacts, 2) physical effects, 3) psychosocial effects, 4) clinical management, 5) information and support needs, and 6) access.

Financial toxicity of cancer treatment (the ongoing negative effects from financial burden) is an emerging area of global concern, particularly as the cost and complexity of cancer treatments increase [29-31]. Almost all participants were impacted financially by OOP expenses, reporting both direct costs (e.g., treatment) and indirect costs (e.g., accommodation), as described in Theme 1. Australians living in rural areas are less likely to have private health insurance and have greater out-of-pocket expenses compared to their metropolitan counterparts [32, 33]; however, participants in our sample largely did not consider treatment costs to be a significant burden. No participants in our study accessed emerging or experimental therapies not subsidized by the public health system, which increased out-of-pocket treatment costs significantly [34]. The burden of indirect costs described by participants (e.g., transport, parking, accommodation, meals, and time off from work) is consistent with a previous study of rural cancer patients in Western Australia [35]; however, this study did not include people with HNC. Compared to people living in metropolitan areas, rural patients may experience greater indirect costs due to the greater need for travel and accommodation and loss of income for both patients and carers [36], with the reimbursement from government schemes such as IPTAAS often described as insufficient. In recent years, the NSW Government has reformed IPTAAS [37], increasing the proportional reimbursement to people through the scheme. Therefore, further analysis of recent experiences of people using IPTAAS is needed to explore whether there has been a perceptible change from the perspectives of patients and carers. In addition, healthcare professionals are an important source of information about financial assistance programs [38], which can alleviate financial toxicity. However, some participants were unaware that these programs existed, so further education of healthcare professionals and patients about financial assistance schemes may be warranted.

The interplay of physical and psychosocial impacts of HNC (Themes 2 and 3) was evident among our cohort, and this aligns with research conducted in Queensland [17]. People with HNC are at high risk of psychosocial distress due to the complex physical and functional side effects of the cancer and its treatment [39, 40]. More than half of the cohort received radiotherapy, which may lead to acute side effects and subsequent psychological distress that peaks towards the end of treatment and gradually decreases over time [41-43]. Very few participants felt their psychological needs were adequately addressed after treatment, despite reporting a high level of care coordination between specialist disciplines. This represents a significant gap and opportunity for improvements in survivorship care [44]. Rural HNC survivors have previously identified the need for psychosocial support [41], with some evidence supporting the use of cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation (providing information about cancer and its treatment to improve knowledge and reduce uncertainty) for HNC patients, with other therapies shown to be of benefit in other cancer populations [45-47]. Participants reported being receptive to written information throughout treatment and posttreatment survivorship, which may indicate support for psychoeducation in this setting and address some of the gaps in information provision identified in Theme 5.

Participants also found ongoing medical support was enhanced by trust in and close relationships with their GP, which was a concept that emerged in Theme 4. The role of the GP in the ongoing management of cancer is greater in rural communities than in metropolitan populations [48, 49]. Despite this, participants noted a knowledge gap in GP for aspects of their survivorship care, which was unsurprisingly due to the general prevalence and diversity of HNC in rural primary care settings [50]. Interventions that target GP knowledge of the survivorship burden for HNC survivors may be beneficial to address this gap. Shared care, in which posttreatment survivorship care is jointly provided by primary care and oncology specialists, has been shown to be successful in early colorectal and prostate cancer [51, 52] and could be considered for some people with HNC. However, given the relative rarity of HNC, GPs and oncology specialists may not feel comfortable with this model until there is stronger evidence of effective surveillance biomarkers (e.g., ctDNA testing) [53]. However, given the role of GPs in the management of chronic conditions described by our sample, shared care may be appropriate for some aspects of care for some patients. According to a 2024 position statement by the Royal Australasian College of General Practitioners, shared care can effectively provide holistic and comprehensive care coordination if elements such as survivorship care plans, role clarification, and patient-specific guidance are included [54].

As described in Theme 5, participants reported the need for additional support for practical aspects of survivorship and information tailored to their circumstances. As described above, the GP (in concert with oncology specialists) plays a central role in providing holistic and comprehensive care, encompassing management of physical and psychosocial effects, management of chronic conditions, and surveillance and detection of recurrence. Support groups are another source of information and support, with HNC survivors previously identifying the importance of support groups to promote camaraderie through shared experiences [55, 56], which was echoed by participants in this study. Social and practical support from family, community, and spiritual groups provided participants with emotional and practical support, as well as acting as a driver for participants to “get better” [57, 58]. Despite this, very few participants accessed formal support groups beyond finishing their treatment, even while experiencing long-lasting side effects. Face-to-face support groups for HNC survivors may be particularly challenging in rural areas, where the prevalence of HNC may be too low to support these groups or require survivors to travel some distance. People with HNC have previously identified the utility of online support groups [59], which may help increase the capacity for rural HNC survivors to access these supports without long-distance travel [20]. More broadly, support from friends and community may reduce social and emotional distress in HNC survivors, increasing confidence in appearance and acting protectively against psychological distress [58, 60].

Access (described in Theme 6) was a concept that overlapped with many other themes in this study. The centralization of specialist services away from participants' homes presents challenges, particularly regarding the need to travel away from this support network, which can detrimentally impact patients. However, it is also important to note that centralization of specialist services to metropolitan cities comes with significant travel costs [36], as observed in this cohort (described in Theme 1). Research has shown that rural patients express the benefits of receiving specialized care closer to home if the services are on par with metropolitan cancer centers [61], a sentiment that was noted in the current study. The co-location of services closer to home and patient accommodation during treatment may serve as a vital intervention point to mitigate the burden of travel costs for rural patients. Outreach clinics, in which oncology specialists travel to rural hubs and provide pre- and posttreatment management, have been successful in NSW for HNC, providing access for rural patients to oncology specialists locally [62].

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

This research addresses an important gap regarding documenting the general long-term survivorship experiences for HNC survivors living in rural areas. Little is known about their long-term needs, with most specialist follow-up care ending 5 years posttreatment, and most research focusing on this initial period [63]. Most of this cohort (60%, n = 10) were more than 5 years post-diagnosis and continued to have long-term cancer-related survivorship needs. More generally, this research adds to evidence for the patient preferences, and benefit for access to local specialist services, despite increasingly centralized cancer services in Australia. Purposive sampling produced a high degree of diversity within the cohort in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and gender of participants and saturation was achieved for a variety of themes, representing inner regional experiences.

There was a low number of participants from outer regions and a lack of participants from remote or very remote areas. This was a function of the small number of HNC survivors in the recruitment pool (eight remote and one very remote). Future studies could target recruitment specifically to these areas to understand the unique survivorship experiences and needs of this group. Other limitations of this study include the potential for recall and survival biases. Recall bias—with most participants more than 5 years post-diagnosis—may have influenced the results, with participants potentially unable to recall, or incorrectly recalling, some aspects of their care. Similarly, survival bias may cause participants to remember experiences more positively than individuals living with longer-term, more severe side effects. In addition, as this study recruited from only four sites/rural hospitals, with limited geographic variability, further research is needed to explore whether experiences are consistent with broader rural populations. Future studies may also consider a more focused comparison between the rural and urban experience of HNC survivorship to gain further insights into experiences that are uniquely rural or urban, as well as an investigation into any specific differences in the experiences of short- and long-term survivors of HNC to understand how needs and experiences change over time. A longitudinal, rather than cross-sectional, qualitative approach, could be used in future studies to address this latter point.

5 Conclusion

Rural cancer survivors living further from specialist care face unique survivorship concerns. Experiences of survivorship care for people with HNC in rural areas highlight unmet needs in financial reimbursement, psychosocial services and support, and access to survivorship care closer to where they live. However, participants largely reported positive experiences with the care they received during their treatment. Future research could target outer regional, remote, and very remote HNC survivors and, more generally, explore psychosocial services and experiences from a systems and service-level perspective. Policy implications of this work include the provision of services and cancer centers outside of metropolitan areas, increasing access to specialist HNC care within rural NSW.

Acknowledgments

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.