Mitigating Road Barrier Effects for Small Mammals: Evidence From Wildlife Passages in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest

Funding: This work was supported by Coordenaçatilde;o de Meio Ambiente Arteris S. A. Concremat Ambiental.

ABSTRACT

Roads significantly impact wildlife through collisions and habitat fragmentation. Wildlife crossing structures aim to mitigate these impacts, but their effectiveness for Neotropical small mammals is largely unknown. During 12 months, we monitored small mammal movements near overpasses, underpasses, and areas without structures (controls) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, using capture-mark-recapture. We quantified highway crossings, structure use without crossing, and structure avoidance. Eight small mammal species were recorded, among which were four forest specialists. The marsupials Didelphis aurita and Marmosa paraguayana used overpasses, while the water rat Nectomys squamipes and the four-eyed opossum Philander quica used underpasses. However, only 5%–7% of marked individuals of the latter two species crossed the highway. The remaining four species (Akodon cursor, Metachirus myosurus, Monodelphis cf. iheringi, and Mus musculus) did not use the structures and were uncommon in roadside habitats. The results suggest that locally abundant forest small mammals avoiding roads can use crossing structures, potentially improving population connectivity compared to areas without them. However, rare forest specialists that did not use the passages may require more substantial interventions to enhance their connectivity. This research provides evidence for potential benefits of crossing structures for Neotropical small mammals while highlighting the need for tailored solutions for different species.

1 Introduction

Wildlife roadkills are among the main causes of mortality in South American mammals, especially in Brazil, where almost 9 million mammals are killed every year (Pinto et al. 2022). Furthermore, the division of formerly continuous forests by roads can isolate animal populations, affecting their genetic diversity and threatening their long-term persistence (Ascensão et al. 2016). Species with low population sizes and reduced reproductive rates may then not persist in the face of the high extinction and low recolonization rates in the fragments separated by roads (Fahrig and Rytwinski 2009).

A procedure frequently implemented to mitigate road impacts on wild animals is the construction of canopy bridges (overpasses) and tunnels (underpasses) (Rytwinski et al. 2016). These structures are designed to allow animals to safely cross the road without facing the risk of collisions with vehicles. In Brazil, this mitigation measure has shown potential to facilitate the movements of arboreal primates (Secco et al. 2022) and of medium-large size non-volant mammals (Alves et al. 2021). However, no information is available regarding the efficiency of underpasses and overpasses to allow crossing movements by non-volant small mammals, such as rodents and marsupials with different locomotory habits and habitat preferences (Soanes et al. 2024).

In the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, many rodent and marsupial species depend on forest cover for their survival (Pardini et al. 2005) and are vulnerable to the effects of habitat loss and fragmentation caused by roads (Rosa et al. 2017). Therefore, studies evaluating the potential of crossing structures to mitigate the impacts of roads on this group of mammals are greatly needed in order to determine which species can benefit from these mitigation measures. In this paper, we evaluated which species use the overpasses (O) and underpasses (U) implemented along a section of the BR-101/North road in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and, among those species that use the structures, which ones use them to cross the highway.

2 Materials and Methods

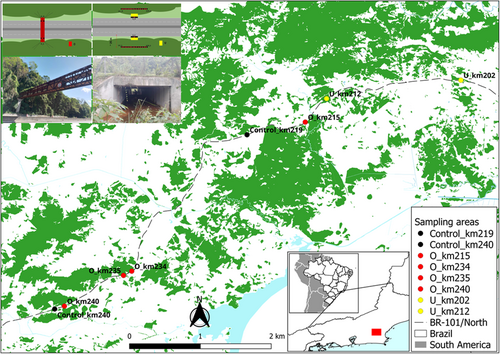

The BR-101 is one of the main federal roads in Brazil that runs along several coastal states. It crosses the entire Rio de Janeiro state and a large part of its section has four lanes of traffic travelling, including the section that connects the state capital to the northernmost portion (Secco et al. 2024). 26 U and 10 O were built to reduce roadkill rates along a 71 km of BR-101/North RJ that is located in the ‘Área de Proteção Ambiental do Rio São João e do Mico Leão Dourado’ (APA), in the municipalities of Rio Bonito, Silva Jardim, Casimiro de Abreu and Rio das Ostras. O structures consist of metal or concrete bridges with a total length of 40 m, and U structures consist in underground concrete tunnels or adapted corridors under road bridges with approximately 35 m length. All O are connected to neighbouring trees by ropes, while all U have fences on the outside that funnel the passage of fauna to the entrance of the crossing structure.

We selected O, U and control areas presenting humid forested areas on both sides of the road. The interior of U structures was partially flooded throughout the sampling period.

We sampled eight areas throughout 1 year, from September 2022 to August 2023, two of them without any crossing structures (control areas), two U and four O (Figure 1). Each one of the eight areas was sampled every 3 months (four sampling sessions for each area), with U and control areas always sampled simultaneously. The sampling design applied in the U and control areas consisted of two linear transects installed parallel to the road and at opposite sides, at approximately 25 m from the road pavement. Each transect had 15 sampling stations, 5 m apart from each other. Each sampling station had a Sherman (30 × 8 × 9 cm) and a Tomahawk (45 × 16 × 16 cm) live-capture trap, all of which were installed on the ground along the linear transect. In the U areas, four additional traps (two alternated pairs of Tomahawk and Sherman traps) were placed within the wildlife passage and near both of its entrances, totaling a daily effort of 64 traps. As control areas lacked crossing structures, the daily effort was 60 traps. Sampling of O areas differed from U and control areas, due to the space available for trap installation on O structures or on roadsides. It relied exclusively on two pairs of Sherman and Tomahawk traps installed along the structure, near both of its entrances during sampling. Two O areas had only Shermans, because Tomahawks could accidentally capture and disrupt the movement behaviour of diurnal and endangered primates, such as the Golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia), which were not the focus of this study.

The U, control and O areas received a total sampling effort of 448, 420 and 112 trap-nights, respectively. The sampling effort in O areas was considerably smaller, and this limitation may have influenced the low number of movements detected. All traps remained open day and night and were baited with mixtures of banana, ground peanuts, sardines and corn flour, and were inspected and replaced once every 24 h for 7 days. Each captured individual was marked with a numbered ear-tag and had species, sex, weight, age and body measurements recorded. Three types of movements were inferred based on the capture-recapture history of marked individuals: (1) ‘Non-crossing’—captures of an individual on sampling stations at the same roadside and outside the crossing structure; (2) ‘Structure use’—capture of an individual inside the U or the O that may or may not cross the highway; and (3) ‘Crossing’—captures of an individual at opposite roadsides of the highway. For individuals captured on O, only ‘No-crossing’ and ‘Crossing’ types of movements were inferred.

The frequency of individuals that performed each type of movement was calculated by dividing the number of individuals of a species that performed a given movement in one area by the total number of recorded individuals at that area. To test whether the presence of U and O increases the likelihood of recording crossing movements at each sampling session, we fitted a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) in which crossing movement was the binomial response variable (0 = no-crosses, 1 = crosses), the presence/absence of U or O was the predictor, and the area as the random effect. Then, we assessed the statistical significance of this GLMM by comparing it with an intercept-only model (null model) by means of a Likelihood ratio test (LRT) with the significance level (p) of 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted on software R 4.3.0 using packages ‘AICmodavg’, ‘MuMIn’, and ‘epiDisplay’.

3 Results and Discussion

Eight species of small non-volant mammals were recorded in the sampling areas, three rodents and five marsupials (Table 1). Crossing movements in U or O were recorded for Didelphis aurita, Philander quica, Marmosa paraguayana, and Nectomys squamipes, while the remaining species performed only non-crossing movements outside the passage structures. No crossing movements were recorded in control areas. The likelihood of recording crossing movements of small mammals per sampling session was significantly higher in U areas than in control areas (X2 = 4.81, d.f. = 1, p = 0.02), but not in O areas (X2 1.71, d.f. = 1, p = 0.19), although crossing movements were recorded on two sessions on O.

| Captures (Individuals) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Underpass km 202 | Underpass km 212 | Control km 240 | Control km 219 | Overpass km 215 | Overpass km 234 | Overpass km 235 | Overpass km 240 | Total |

| Rodentia | |||||||||

| Akodon cursor (Winge, 1887) | 0 | 2 (1) | 16 (10) | 9 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 (16) |

| Nectomys squamipes (Brants, 1827)* | 40 (11) | 27 (11) | 47 (14) | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 117 (39) |

| Mus musculus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Didelphimorphia | |||||||||

| Didelphis aurita (Wied-Neuwied, 1826)* | 1 (1) | 28 (12) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 42 (21) |

| Philander quica (Temminck, 1824)* | 14 (7) | 26 (8) | 18 (5) | 35 (13) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 94 (34) |

| Marmosa paraguayana (Tate, 1931) | 9 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 9 (3) |

| Metachirus myosurus (Temminck, 1824) | 0 | 6 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (2) |

| Monodelphis cf. iheringi | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Total | 64 (21) | 89 (34) | 89 (36) | 48 (22) | 7 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) | 299 |

- Note: The asterisk indicates which species were the most abundant.

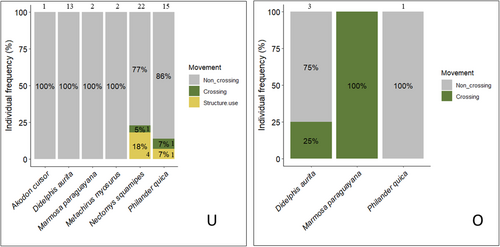

Nectomys squamipes and Philander quica were the only species that performed crossings in U areas (Figure 2; Table 1). Different individuals of N. squamipes (18% of the individuals marked) used U, but only one (5% of the individuals marked) performed crossings (Figure 2). For P. quica, both structure use and crossings had low frequency (7%) (Figure 2). The use of U by N. squamipes was possibly due to the partial flooding of these structures, given that this species has a semi-aquatic lifestyle (Briani et al. 2001). Although P. quica is not semi-aquatic, it prefers more humid habitats (Moura et al. 2005), which could explain the use of semi-flooded passages by this species. The structure use and crossing movement recorded for P. quica were performed by an adult male. The same occurred for N. squamipes, in which all individuals that used the structure or performed crossings were males. These two species were also common in the control areas, although they never performed crossings in these areas (Table 1).

Few captures were recorded on O and only five movements could be inferred for Didelphis aurita and Marmosa paraguayana, three as crossing movements (Table 1). One individual of Philander quica was also captured on one O, but without further recaptures to infer its movements. Crossing was the only movement recorded for the single individual M. paraguayana captured, while the two individuals of D. aurita performed both crossing (25%) and non-crossing (75%) movements (Figure 2). Likely, the more limited sampling on O hindered robust inferences about their effectiveness. Other arboreal small mammal species seldom trapped by live traps might use them, as suggested by camera trap data (Melo-Dias et al. 2023). Nonetheless, our results show that few individuals per species might perform crossing movements.

Similarly to the crossing movements recorded in U areas, all crossings of D. aurita and M. paraguayana in O areas were performed by adult males. Adult males of these two species generally move more than adult females (Arias et al. 2023; Loretto and Vieira 2005). Movements over greater distances by males of small mammals are generally attributed to searching for sexual partners, while females tend to be more restricted to a territory (Pires and Fernandez 1999).

Previous studies of small mammals in Brazilian Atlantic Forest fragments have shown that P. quica, M. paraguayana and N. squamipes seldom cross non-forest anthropogenic habitats (Arias et al. 2023; Pires et al. 2002). Also, roadkill monitoring data indicate that these species are rarely recorded among roadkills (Secco et al. 2024), suggesting that they avoid the road space as a hostile space or barrier. D. aurita, the fourth species recorded using the structures, differs from the other three by exhibiting higher vagility and tolerance to anthropogenic habitats (Astúa et al. 2015). Consequently, this species frequently uses road space and shows little or no road avoidance behaviour, as suggested by its high incidence among roadkills (Secco et al. 2024). Despite the presence of D. aurita in U areas and its higher vagility, crossing movements were performed only on O, suggesting that this type of crossing structure might be more effective than U. Except for Akodon cursor, which was locally abundant, the low abundance of Metachirus myosurus, Monodelphis cf. iheringi, and Mus musculus on roadside habitats also indicates road avoidance behaviour by these marsupials, especially in the case of M. myosurus and M. cf. iheringi, which are forest specialists that avoid open or uncovered areas (Vieira et al. 2009).

Although four of the eight species recorded in this study were able to use O or U to cross the road, the frequency of individuals of each species using U and O to cross the road is nonetheless low. In U areas, the proportion of individuals crossing the road (5%–7% of marked individuals) is close to the ones observed in wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) populations separated by roads in Europe (Galantinho et al. 2022), and suggests that the BR-101/North RJ still constitutes a ‘soft barrier’ for small mammal species that are able to cross the road using crossing structures. However, if subpopulations at opposite roadsides are large, a migration rate of 5% might be sufficient to prevent further divergence and loss of genetic variation (Ascensão et al. 2016) and already represents a positive impact of the mitigation measures adopted in relation to the previous road scenario (without wildlife safe passages). If corroborated by genetic studies, this scenario might indicate a contribution to genetic connectivity to species that would otherwise remain subdivided by the road. On the other hand, improving connectivity for small mammal species that did not use O and U should be more challenging, as it might involve the construction of larger crossing structures, such as forested viaducts, coupled with habitat restoration.

Author Contributions

Ian Moreira Souza: investigation, methodology, writing – original draft. Victoria Bartolome: investigation, methodology, writing – original draft. Rodrigo Delmonte Gessulli: investigation, methodology, writing – original draft. Marcelo Guerreiro: data curation, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision. Thiago de Oliveira Machado: data curation, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision. Helio Secco: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision. Pablo Rodrigues Gonçalves: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing – original draft.

Acknowledgements

We pay respects to everyone involved with the conservation of natural environments in the Rio de Janeiro landscapes fragmented by BR-101, mainly ‘Coordenação de Meio Ambiente Arteris S. A.’, ‘Concremat Ambiental’ and ‘NUPEM/UFRJ’ who made this work possible. We also thank the financial support provided by FAPERJ (E-26/200.415/2023) through the “Cientista do Nosso Estado” award to Pablo Rodrigues Gonçalves. The Article Processing Charge for the publication of this research was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) (ROR identifier: 00x0ma614).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study cannot be shared publicly due to institutional restrictions. Requests for access should be directed to the corresponding co-authors who hold the data.