Efficacy and safety of alogliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A multicentre randomized double-blind placebo-controlled Phase 3 study in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong

阿格列汀治疗2型糖尿病患者的疗效和安全性:在中国大陆,台湾,香港进行的一项多中心随机双盲安慰剂对照的3期研究

Abstract

enBackground

This study determined the efficacy and safety of once-daily oral alogliptin in patients from mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

In this Phase 3 multicenter double-blind placebo-controlled 16-week trial, 506 patients were randomized to receive once-daily alogliptin 25 mg or placebo: 185 in the monotherapy group, 197 in the add-on to metformin group, and 124 in the add-on to pioglitazone group. The primary efficacy variable was the change from baseline (CFB) in HbA1c at Week 16; other efficacy measures included CFB to Week 16 in fasting plasma glucose (FPG), incidence of marked hyperglycemia (FPG ≥11.1 mmol/L), and the incidence of clinical HbA1c ≤6.5 % (48 mmol/mol) and ≤7.0 % (53 mmol/mol) at Week 16. Safety was assessed throughout the trial.

Results

Alogliptin monotherapy provided a significantly greater decrease in HbA1c from baseline to Week 16 compared with placebo (−0.58 %; 95 % confidence interval [CI] –0.78 %, −0.37 %; P < 0.001). As an add-on to metformin or pioglitazone, alogliptin also significantly decreased HbA1c compared with placebo (−0.69 % [95 % CI −0.87 %, −0.51 %; P < 0.001] and −0.52 % [95 % CI −0.75 %, −0.28 %; P < 0.001], respectively). In any treatment group versus placebo, alogliptin led to greater decreases in FPG (P ≤ 0.004) and a higher percentage of patients who achieved an HbA1c target of ≤6.5 % and ≤7.0 % (P ≤ 0.003). No weight gain was observed in any treatment group. A similar percentage of patients experienced drug-related, treatment-emergent adverse events in the alogliptin and placebo arms. Four and two patients in the alogliptin and placebo arms, respectively, experienced mild or moderate hypoglycemia.

Conclusions

Alogliptin 25 mg once daily reduced HbA1c and FPG and enhanced clinical response compared with placebo when used as monotherapy or as an add-on to metformin or pioglitazone. Therapy with alogliptin was well tolerated.

Abstract

zh背景: 本研究的目的是在中国大陆、台湾和香港的2型糖尿病患者中考察口服阿格列汀每日一次的疗效和安全性。

方法: 在这项为期16周的多中心双盲安慰剂对照3期研究中,506名患者被随机分为接受阿格列汀25 mg每日一次或安慰剂治疗:185人接受单药治疗,197人联合二甲双胍治疗,124人联合吡格列酮治疗。主要疗效终点为16周时HbA1c与基线相比的变化,其他疗效指标包括16周时空腹血糖(FPG)与基线相比的变化,高血糖发生率(FPG ≥ 11.1 mmol/L)和16周时临床HbA1c ≤ 6.5 %(48 mmol/mol) 和 ≤ 7.0 %(53 mmol/mol) 的患者比例。在整个研究中评估安全性。

结果: 阿格列汀单药治疗与安慰剂相比可使HbA1c与基线相比显著降低(-0.58%;95% CI:-0.78%,-0.37%;P < 0.001)。作为二甲双胍或吡格列酮的联合治疗,阿格列汀与安慰剂相比仍然可使HbA1c从基线显著降低(分别为-0.69 % [95% CI:-0.87%,-0.51%];P < 0.001和-0.52 % [95% CI:-0.75 %,-0.28 %;P < 0.001])在每个治疗组中,与安慰剂相比,阿格列汀均可使FPG显著降低(P ≤ 0.004)。HbA1c达标的患者比例更高 (HbA1c ≤ 6.5 %和 ≤ 7.0 %,P ≤ 0.003)。在各组都没有观察到体重的增加。在阿格列汀和安慰剂组有一小部分的患者发生了与药物和治疗相关的不良反应。在阿格列汀和安慰剂组中各有4名和2名患者发生了轻度或中度的低血糖.

结论: 阿格列汀每日25 mg与安慰剂相比可降低HbA1c和 FPG,提高患者的临床反应,无论是单药治疗还是联合二甲双胍或吡格列酮。阿格列汀治疗具有良好的耐受性。

Significant findings of the study: This study demonstrated that alogliptin provides additional efficacy in improving key efficacy parameters, including HbA1c, FPG, and clinical response, without an increase in adverse events compared with placebo.

What this study adds: This study provides important data on Asian patients to the clinical profile of alogliptin.

Introduction

Worldwide, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has increased markedly in recent decades. China is estimated to have 113.9 million adults with diabetes and an additional 493.4 million adults with prediabetes (i.e. impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance).1 Up to 70 % of these cases were previously undiagnosed, suggesting an imminent epidemic of this metabolic condition.1 In Taiwan, in 2007, the prevalence of T2DM was estimated to be 8.3 % (1.6 million cases), an increase of 43 % from 2000.2 In 2015, in Hong Kong, 582 500 adults had T2DM, a prevalence of 10.2 %.3 Achievement of an HbA1c level of <7 %, a goal set by the American Diabetes Association,4 has been suboptimal. In 2006, only 41.1 % of Chinese patients achieved this goal.5 Greater success in achieving this goal has been reported in Hong Kong (56.5 % in 2013),6 whereas in Taiwan only 34.6 % of patients achieve an HbA1c of <7 %.7

Alogliptin is a potent, highly selective, orally available inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP)-4.8 Through sustained inhibition of DPP-4,8 alogliptin has the potential to increase circulating levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), as has been shown with other DPP-4 inhibitors (i.e. vildagliptin and sitagliptin).9 By enhancing glucose-dependent stimulation of insulin secretion, suppressing glucose-dependent glucagon secretion, and delaying gastric emptying, GLP-1 works to maintain glucose homeostasis.9-11 In animal studies, GLP-1 also stimulated the proliferation and differentiation of pancreatic β-cells and inhibited β-cell apoptosis.10

The efficacy and safety profile of alogliptin have been well documented in mostly Western populations12-18; however, the evidence in Asian populations is quite limited, despite some published studies in Japan.19-21 Increasingly, data suggest that the pathophysiology of T2DM differs across various ethnic groups.22-24 Compared with non-Asian patients, Asian patients are characterized by a relatively lower body mass index (BMI)19 and higher amounts of visceral fat even when BMI values are similar.25, 26 Further, Asian patients with impaired glucose tolerance and T2DM exhibit a predominant insulin secretory defect.27-29 More data from Asian patients are needed to broaden the clinical profile of alogliptin. The present study is the largest Phase 3 study to date to evaluate the efficacy and safety of alogliptin compared with placebo when given as monotherapy, added on to metformin, or added on to pioglitazone (with or without metformin) in patients with T2DM in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

Methods

Patients

Patients eligible for inclusion in the present study were men or women aged 18–75 years with a historical diagnosis of T2DM and inadequate glycemic control. Patients experiencing inadequate glycemic control were defined as those with an HbA1c between 7.0 % and 10.0 % (inclusive). At screening, patients had to meet one of the following criteria: (i) for the monotherapy group, patients had to have been treated with diet and exercise for at least 2 months prior to screening (receiving <7 days of any antidiabetic medication within 2 months prior to screening); (ii) for the add-on to metformin therapy group, patients had to have been treated with a stable dose of metformin (≥1000 mg/day) for at least 3 months; and (iii) for the add-on to pioglitazone therapy group, patients had to have been treated with a stable dose of pioglitazone alone or in combination with metformin. Both the pioglitazone and metformin groups must have been on a stable dose for at least 8 weeks prior to screening. Other key inclusion criteria included a BMI between 20 and 45 kg/m2, systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≤ 180/≤110 mmHg, and serum creatinine <132.6 μmol/L in men and <123.8 μmol/L in women.

Key exclusion criteria included a history of treated diabetic gastroparesis, New York Heart Association Class III or IV heart failure or a history of coronary angioplasty, coronary stent placement, coronary bypass surgery or myocardial infarction within 6 months, or significant clinical symptoms of hepatopathy or renal impairment.

Study design

The present study was a Phase 3 double-blind multicenter study conducted from December 2010 to December 2011 (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT01289119). All patients entered a screening period of up to 2 weeks, followed by a 4-week placebo run-in period in a single-blind manner. Eligible patients were stratified into one of three therapy groups before being randomized 1:1 to receive either alogliptin 25 mg once daily or matching placebo once daily. The therapy groups were: (i) monotherapy; (ii) add-on to metformin; and (iii) add-on to pioglitazone (with or without metformin). After completion of the placebo run-in period, patients entered a 16-week treatment period, during which they received blinded study drug as well as dietary and exercise coaching.

Randomization to treatment groups was achieved using an interactive voice or interactive web response system. Patients were instructed to take study drug in the morning before breakfast.

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guideline, and applicable local regulatory requirements of each participating region. All patients reviewed and signed informed consent forms prior to administration of any study drug.

Efficacy and safety endpoints

For each therapy group, the primary efficacy endpoint was the change from baseline in HbA1c at Week 16. Secondary efficacy endpoints were other measures of glycemic control, including change from baseline to Week 16 in fasting plasma glucose (FPG), incidence of marked hyperglycemia (FPG ≥11.1 mmol/L), and the incidence of clinical HbA1c ≤6.5 % (48 mmol/mol) and ≤7.0 % (53 mmol/mol) at Week 16. Differences in change from baseline to Week 16 (or early termination) in body weight were also analyzed. In addition, a subgroup analysis for the primary efficacy endpoint was performed for baseline HbA1c (<8 % or ≥8 %), sex, and age at baseline (<65 or ≥65 years). Both HbA1c and FPG were measured at baseline, during Week −1 of the placebo run-in, on Day 1 (first day of double-blind dosing), and at Weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16 of the treatment period.

Safety endpoints were as follows: incidence of adverse events (AEs); incidence of hypoglycemia; physical examination findings; vital sign measurements; 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) tracings; and clinical laboratory evaluations (hematology, serum chemistry, and urinalysis). All AEs were rated by the investigator for intensity and relationship to study drug. Mild-to-moderate hypoglycemia, whether symptomatic or asymptomatic, was defined as plasma glucose levels <3.9 mmol/L. Severe hypoglycemia was defined as any hypoglycemic episode that required the assistance of another person to actively administer carbohydrate, glucagon, or other resuscitative actions, and was associated with a documented plasma glucose level < 3.9 mmol/L.

Statistical analysis

As planned, approximately 480 patients were to be randomized 1: 1 to alogliptin or placebo, with 160 randomized in each therapy group (80 per treatment arm). This sample size ensured at least 94 % power to detect a difference of 0.45 % between alogliptin 25 mg once daily and placebo once daily within each therapy group, assuming a standard deviation of 0.8 % and a two-sided 5 % significance level. Ultimately, the add-on to pioglitazone (with or without metformin) therapy group randomized only 124 patients. Prospectively, this sample size provided 87 % power to detect the treatment difference between alogliptin and placebo described above with the same assumptions in this therapy group.

The primary analysis was conducted separately for each therapy group using the full analysis set (FAS) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models. For each therapy group, the primary analysis compared alogliptin 25 mg once daily to placebo once daily derived from the corresponding ANCOVA models using a two-sided 5 % significance level without multiplicity adjustment. Missing data were imputed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF). A supportive analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint was also conducted using the primary analysis models specified above and the per-protocol set (PPS), which included all patients in the FAS who had no major protocol violations. The secondary continuous endpoints were analyzed using models similar to the primary analysis models. The hyperglycemia incidence variable was analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) by treatment arm for each therapy group, and treatment comparisons were conducted with logistic regression models analogous to the primary efficacy models. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, the incidence of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), and the incidence of hypoglycemia, physical examination findings, vital signs, 12-lead ECG readings, and clinical laboratory evaluations.

Results

Patient disposition and characteristics

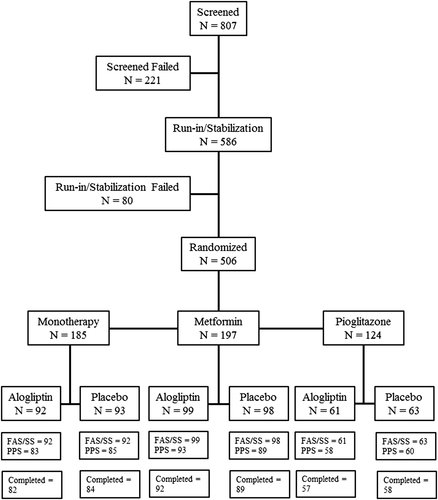

In all, 807 patients were screened and 586 patients entered the placebo run-in period. After the run-in period, 506 patients were randomized as follows: 185 patients in the monotherapy group (92 and 93 in the alogliptin and placebo arms, respectively), 197 patients in the add-on to metformin therapy group (99 and 98 in the alogliptin and placebo arms, respectively), and 124 patients in the add-on to pioglitazone therapy group with or without metformin (61 and 63 in the alogliptin and placebo arms, respectively). In the pioglitazone therapy group, 24 patients were treated with placebo or alogliptin without metformin; the others were treated with placebo or alogliptin with metformin (Fig. 1). In the monotherapy, metformin add-on, and pioglitazone add-on treatment arms, 18 (9.8 %), 15 (7.6 %), and nine (7.3 %) patients prematurely discontinued the study, respectively. The most common reasons for study discontinuation in the monotherapy, metformin add-on, and pioglitazone add-on treatment arms were voluntary withdrawal (six, seven, and two patients, respectively), major protocol deviations (three patients in each group), AEs (three, two, and one patient, respectively), lack of efficacy (defined as those who met hyperglycemic rescue criteria [see details in the Supplementary Material to this paper]; one, two, and two patients, respectively), and lost to follow-up (three, none, and one patient, respectively).

In the present study, 97 % of patients were from mainland China, 2 % were from Hong Kong, and 1 % were from Taiwan. There were no major differences in baseline age, gender, BMI, baseline HbA1c level, or T2DM duration between the alogliptin and placebo arms in the three therapeutic groups (Table 1). There were no differences between the alogliptin and placebo arms in the daily dose of metformin.

| Monotherapy | Metformin therapy | Pioglitazone therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 92) | Alogliptin (n = 92) | Placebo (n = 98) | Alogliptin (n = 99) | Placebo (n = 63) | Alogliptin (n = 61) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 53.1 ± 8.9 | 51.6 ± 10.4 | 53.2 ± 9.5 | 53.0 ± 9.9 | 51.8 ± 10.4 | 52.6 ± 9.4 |

| No. (%) <65 | 81 (87.1) | 80 (87.0) | 86 (87.8) | 85 (85.9) | 56 (88.9) | 52 (85.2) |

| No. (%) ≥65 | 12 (12.9) | 12 (13.0) | 12 (12.2) | 14 (14.1) | 7 (11.1) | 9 (14.8) |

| No. (%) men | 54 (58.1) | 55 (59.8) | 48 (49.0) | 51 (51.5) | 39 (61.9) | 28 (45.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 3.0 | 25.8 ± 3.1 | 25.5 ± 2.9 | 25.8 ± 3.1 | 26.1 ± 3.0 | 25.3 ± 3.2 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 2.1 ± 2.8 | 1.9 ± 2.4 | 5.3 ± 3.9 | 5.4 ± 4.3 | 4.9 ± 4.7 | 5.8 ± 5.3 |

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 7.86 ± 0.78 | 8.04 ± 0.92 | 7.96 ± 0.75 | 8.00 ± 0.83 | 7.96 ± 0.82 | 7.94 ± 0.91 |

| Daily dose of metformin (mg) | NA | NA | 1484 ± 451 | 1472 ± 417 | 1355 ± 432 (n = 50) | 1295 ± 507 (n = 50) |

| Daily dose of pioglitazone (mg) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21.9 ± 11.4 | 20.2 ± 7.2 |

| Country or region (n [%]) | ||||||

| China | 91 (97.8) | 90 (97.8) | 94 (95.9) | 92 (92.9) | 63 (100.0) | 61 (100.0) |

| Hong Kong | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.0) | 4 (4.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Taiwan | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 3 (3.0) | 0 | 0 |

- Data are given as the mean ± SD or as n (%).

- BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable.

Efficacy endpoints

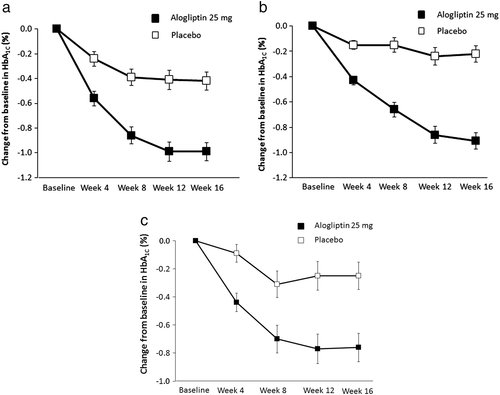

The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in HbA1c at Week 16 in the monotherapy, add-on to metformin, and add-on to pioglitazone groups. Baseline HbA1c levels and analysis of change from baseline in HbA1c in the FAS population for the monotherapy group are shown in Fig. 2a. At Week 16, alogliptin treatment resulted in the reduction of HbA1c by 0.99 %, whereas placebo reduced HbA1c by 0.42 %. The difference in the changes between the two arms was −0.58 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] –0.78 %, −0.37 %; P < 0.001). Figure 2b shows the change from baseline in HbA1c in the add-on to metformin therapy group. Treatment with alogliptin for 16 weeks reduced HbA1c by 0.91 %, whereas placebo resulted in a 0.22 % decrease from baseline. The difference between the changes in the two arms was −0.69 % (95 % CI −0.87 %, −0.51 %; P < 0.001). Analysis of change from baseline in HbA1c in the add-on to pioglitazone therapy group is shown in Fig. 2c. Alogliptin resulted in a reduction of HbA1c of 0.76 % compared with 0.25 % in the placebo group. The difference between the changes in the two arms was −0.52 % (95 % CI −0.75 %, −0.28 %; P < 0.001).

Results of the primary efficacy analysis in the PPS were consistent with those in the FAS (Table S1). The primary efficacy analysis was also performed using the FAS for subgroups, based on baseline HbA1c (<8 %, ≥8 %), gender (men, women), and age (<65, ≥65 years). The HbA1c reduction with alogliptin was consistent across the baseline HbA1c, gender, and age < 65 years subgroups (Table S2).

At Week 16, alogliptin 25 mg provided significantly greater decreases in FPG compared with placebo in the monotherapy (−0.925 mmol/L; 95 % CI −1.360, −0.491; P < 0.001), add-on to metformin (−0.728 mmol/L; 95 % CI −1.164, −0.291; P = 0.001), and add-on to pioglitazone (−0.957 mmol/L; 95 % CI −1.593, −0.321; P = 0.004) groups (Fig. 3). The percentage of patients who were able to achieve HbA1c targets of ≤6.5 % and ≤7.0 % at Week 16 was significantly higher in the alogliptin arm than in the placebo arm in all treatment groups (Table 2). The incidence of marked hyperglycemia in the FAS was significantly lower in the alogliptin versus placebo arm in all treatment groups (Fig. 4). Mean body weight decreased at Weeks 8 and 16 in both the alogliptin and placebo arms in all groups; however, the difference between the two treatments was not statistically significant (Table 3).

| Monotherapy | Metformin | Pioglitazone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 92) | Alogliptin (n = 92) | Placebo (n = 98) | Alogliptin (n = 99) | Placebo (n = 63) | Alogliptin (n = 61) | |

| HbA1c ≤6.5 % | 12.2 % | 36.7 % | 4.1 % | 21.4 % | 9.5 % | 30.0 % |

| OR (95 % CI) | 6.44 (2.73, 15.2) | 7.92 (2.43, 25.9) | 5.75 (1.82, 18.2) | |||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | |||

| HbA1c ≤7.0 % | 30.0 % | 63.3 % | 25.8 % | 55.1 % | 31.7 % | 61.7 % |

| OR (95 % CI) | 6.77 (3.23, 14.2) | 4.60 (2.34, 9.04) | 5.98 (2.23, 16.0) | |||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

- CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

| Monotherapy | Metformin therapy | Pioglitazone therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 92) | Alogliptin (n = 92) | Placebo (n = 98) | Alogliptin (n = 99) | Placebo (n = 63) | Alogliptin (n = 61) | |

| Baseline mean | 71.16 | 70.79 | 69.42 | 71.66 | 72.44 | 67.42 |

| Week 8 | ||||||

| LS mean | −1.04 | −0.71 | −0.82 | −0.43 | −0.74 | −0.15 |

| LS mean difference | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.59 | |||

| 95 % CI | (−0.26, 0.92) | (−0.08, 0.86) | (−0.13, 1.31) | |||

| Week 16 | ||||||

| LS mean | −1.55 | −0.89 | −1.06 | −0.76 | −0.68 | −0.10 |

| LS mean difference | 0.65 | 0.30 | 0.58 | |||

| 95 % CI | (−0.03, 1.34) | (−0.31, 0.91) | (−0.34, 1.50) | |||

- CI, confidence interval; LS = least squares.

Safety evaluation

Overall, alogliptin and placebo were well tolerated in all treatment groups (Table 4). The majority of TEAEs were of mild intensity and considered unrelated to study drug by the investigators. The TEAEs occurring in ≥3 % of any treatment group are also shown in Table 4. The most commonly reported TEAE was infection, reported by 19 (7.5 %) and 22 (7.5 %) of patients receiving placebo or alogliptin, respectively. No statistically significant differences in the rates of TEAEs were observed between the alogliptin and placebo arms.

| Treatment-emergent AEs by system | Placebo (n = 253) | Alogliptin (n = 252) |

|---|---|---|

| Organ class (safety analysis set) | ||

| With one or more AEs | 99 (39.1) | 92 (36.5) |

| With drug-related AEs | 22 (8.7) | 23 (9.1) |

| With any serious AEs | 6 (2.4) | 3 (1.2) |

| Discontinued due to an AE | 5 (2.0) | 4 (1.6) |

| Discontinued due to study drug-related AE | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Death | 0 | 0 |

| AEs occurring in ≥3 % of any treatment group | ||

| Infections and infestations | 19 (7.5) | 22 (8.7) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 13 (5.1) | 8 (3.2) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 13 (5.1) | 9 (3.6) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 9 (3.6) | 8 (3.2) |

| Nervous system disorders | 8 (3.2) | 5 (2.0) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 9 (3.6) | 5 (2.0) |

| Overview of hypoglycemic events | ||

| Overall | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.6) |

| Mild to moderate | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.6) |

| Symptomatic | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.2) |

| Asymptomatic | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Severe | 0 | 0 |

- Data are given as n (%).

- AE, adverse event.

Eight patients experienced nine serious AEs (SAEs): three patients (1.2 %) in the alogliptin arm compared with five patients (2.0 %) in the placebo arm. The three SAEs in the alogliptin arm were cholangitis, intraductal papilloma of the breast, and lacunar infarction. The six SAEs in the placebo arm were acute pancreatitis, cellulitis, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, intervertebral disc protrusion, and hypertension. All SAEs were determined by investigators to be unrelated to study drugs. Nine patients developed TEAEs leading to discontinuation of study drugs (Table 4). The individual AEs that resulted in discontinuation were arrhythmia, eye edema, asthenia, chest discomfort, face edema, cellulitis, musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, dizziness, dyspnea, and nasal obstruction. All were single events with the exception of two patients in the alogliptin arm who experienced dizziness. No deaths were reported during the study, nor were there any reports of hospitalization due to heart failure in either treatment group.

Four patients in the alogliptin arm (one in the monotherapy group, two in the metformin add-on group, and one in the pioglitazone add-on group) compared with two in the placebo arm (one in the metformin add-on group and one in the pioglitazone add-on group) experienced hypoglycemia (Table 4). All instances were considered mild to moderate in intensity and no events required assistance from others to treat or resulted in discontinuation of study medication.

In terms of physical examination results, no trends or patterns were observed, and there were no apparent differences between therapy groups. No clinically significant changes were observed in the mean values for vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, pulse, and temperature). No clinically significant echocardiography differences were observed between the therapy groups.

Discussion

The present multicenter clinical trial demonstrated greater decreases in HbA1c at Week 16 in the alogliptin arms than in the placebo arms; these differences were not affected by sex or baseline HbA1c. These differences were also significant for patients age < 65 years, but not for those aged ≥65 years, in the add-on groups. The reason for this could be that the number of patients age ≥ 65 years in each group was much lower than that of patients aged <65 years. The improvements in FPG and clinical response were also greater in the alogliptin arms compared with the placebo arms. Furthermore, alogliptin was well tolerated and did not result in a significant increase in AEs compared with placebo. No serum chemistry-related AEs were assessed as moderate, severe, or serious with alogliptin, and no patients discontinued the study due to a serum chemistry-related AE. There were no meaningful changes in vital signs, and no clinically significant differences in 12-lead ECG findings were observed. The low incidence of hypoglycemia reported in the present study is in line with other studies examining the efficacy and safety of alogliptin therapy.12, 20 These data are also similar to results from previous studies that reported no increase in the incidence of hypoglycemia after treatment with alogliptin in the elderly compared with younger patients with T2DM,15 or when added to glyburide,14 metformin,13 pioglitazone,16 or insulin.17 Weight loss was observed in all treatment groups, including placebo. This may be attributed to the clinical study setting; patients were monitored closely to ensure they were compliant with dietary and exercise guidelines.

Alogliptin monotherapy for treatment-naïve patients with uncontrolled T2DM despite diet and exercise therapy for 16 weeks produced significant and clinically meaningful improvements in HbA1c, FPG, and in the percentage of patients who reached HbA1c targets of ≤6.5 % and ≤7.0 %. The effect of alogliptin on other key glycemic parameters was not investigated in the present study, but it has been shown previously that alogliptin is able to produce significantly greater changes compared with placebo in postprandial plasma glucose, glycoalbumin, and 1,5-anhydroglucitol concentrations in Japanese patients with T2DM.20

The addition of alogliptin to metformin improved HbA1c and FPG without increasing the risk for hypoglycemia, gastrointestinal AEs, or weight gain, unfavorable effects generally associated with current T2DM therapies, such as insulin, sulfonylureas, or thiazolidinediones. There were no safety or tolerability concerns with alogliptin as an add-on to metformin in the present study. Metformin is a first-line drug for the treatment of T2DM.4 However, metformin monotherapy may fail to maintain glucose control over time, largely due to progressive loss of β-cell function.30 Alogliptin and other DPP-4 inhibitors enhance pancreatic insulin secretion and reduce glucose output through a suppressive effect on pancreatic glucagon secretion;8, 9 they may also improve β-cell function.10, 11, 31 In obese, non-diabetic subjects, metformin increases circulating total GLP-1 levels.32 Data from diet-induced obese mice and healthy human subjects suggest that DPP-4 inhibition may complement the actions of metformin by inhibiting GLP-1 degradation and inactivation, thereby increasing the concentrations of intact, biologically active GLP-1.33 Additional data are needed to determine whether the therapeutic effectiveness of combination therapy with metformin and DPP-4 inhibitors can further augment the release of GLP-1 in patients with T2DM.

In the alogliptin add-on to pioglitazone group, alogliptin was able to provide additional reduction in HbA1c and in FPG at 16 weeks compared with placebo. The efficacy of alogliptin and pioglitazone in combination can be explained by their complementary modes of action. As an insulin sensitizer, pioglitazone improves insulin resistance and increases peripheral glucose uptake.34 Although Asians have lower BMI compared with non-Asians, when BMI measurements are equal Asians have a higher percentage of visceral fat compared with non-Asian people.25, 26 Because insulin sensitivity decreases with increases in visceral fat,35 the insulin resistance of Asian patients may be more severe than that of non-Asian patients with the same BMI. Short-term treatment with alogliptin and pioglitazone or sitagliptin and pioglitazone in combination has been demonstrated to significantly improve β-cell function and insulin resistance, two core defects of T2DM, in patients with T2DM.36, 37 Thus, combination medications targeting both insulin resistance and insulin secretory defects can be a therapeutic option that also benefits Asian patients. Although pioglitazone has been shown to increase body weight in previous studies,38 in the present study weight gain was not observed in this group. It may be that among the patients who were receiving pioglitazone in combination with metformin, the weight gain that may have been induced by pioglitazone was offset by the weight-reducing effects of metformin.38, 39

The present study had limitations. Pioglitazone is not a first-line therapy, and the number of patients using pioglitazone as monotherapy is relatively low. Only 24 patients in the pioglitazone group were treated with placebo or alogliptin without metformin. The targeted number of randomized patients in the add-on to pioglitazone group was reduced from 160 to 120, which reduced the statistical power in this group. Nevertheless, alogliptin as an adjunct to pioglitazone therapy once daily resulted in improved, meaningful efficacy compared with placebo added to pioglitazone, by leading to significantly reduced HbA1c and FPG with no increase in the number of AEs. Furthermore, similar results have been reported in other alogliptin clinical studies in Japanese and non-Asian patients.16, 18, 19

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that alogliptin can be considered as an initial monotherapy for Asian patients with uncontrolled T2DM despite diet and exercise therapy or as an add-on to metformin or pioglitazone therapies.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company (Beijing, China). The study sponsor supervised patient enrollment and study conduct at the clinical sites and was responsible for conducting data analyses. The authors thank the other study investigators for their important contributions, namely Wei Gu, Zhaoshun Jiang, Mingxiang Lei, Ling Li, Xuefeng Li, Xuejun. Li, Zhengfang Li, Jingdong Liu, Xiaomin Liu, Yu Liu, Zhimin Liu, Xiaofeng Lv, Yongde Peng, Ruifang Bu, Shen Qu, Bingyin Shi, Yongquan Shi, Qinhua Song, Li Yan, Baozhong Zheng, Xiangjin Xu, Yaoming Xue. Editorial support was provided by Dr Meryl Gersh (AlphaBioCom, King of Prussia, PA, USA) and funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

Disclosure

CP has consulted for Takeda, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), and Sanofi; PH has consulted for Takeda; QJ has consulted for Takeda, MSD, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, BMS, and Sanofi; CL has consulted for Takeda, MSD, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, BMS, Sanofi, Novartis, GSK, Johnson & Johnson (J&J), and Boehringer Ingelheim (BI); JL has consulted for Takeda, MSD, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, BMS, Sanofi, Novartis, Roche, GSK, J&J, and BI; JY has consulted for Takeda, MSD, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, BMS, and Sanofi; WL has consulted for Takeda, MSD, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, and BMS; JZ has consulted for Takeda, Novartis, and BI; and JC and AH have consulted for Takeda.