A Scoping Review of the Observed and Perceived Functional Impacts Associated With Language and Learning Disorders in School-Aged Children

Funding: A research trip that allowed exchanges from researchers from Quebec received funding from the GRIPI, the Université of Clermont Auvergne and the Office Franco-Québecois pour la Jeunesse.

ABSTRACT

Background

Assessing children with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) and Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) requires a clear understanding of how these conditions impact their daily lives. However, existing assessment tools are not systematically grounded in a theoretical framework, and there is a lack of consensus regarding the relevant dimensions and indicators to be evaluated. Notably, the concepts of functional impact and functional impairment—which are essential for identifying needs, informing clinical decision-making and tailoring interventions—remain poorly defined and are frequently used interchangeably, even though they refer to distinct aspects of functioning. This conceptual ambiguity hinders the development of consistent, theory-based assessment models and contributes to inconsistencies across both research and clinical settings.

Aims

The study aims to describe and clarify the concepts of ‘functional impact’ and ‘functional impairment,’ as well as to identify and classify the leading dimensions and indicators used to measure the functional consequences of DLD and SLD in school-aged children.

Methods and Procedures

A scoping review was performed on a systematic search of studies published between January 2013 and November 2023 across six databases (Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, Psychology & Behavioural Science Collection and Education Source). In total, 1950 documents were reviewed using predefined eligibility criteria, resulting in 53 documents being included for the final data extraction. The analysis followed a qualitative approach, combining both inductive and deductive analyses. An inductive approach was used to develop a new conceptual framework (definitions and classification system), while a deductive approach was applied to organise the identified dimensions and indicators into five overarching categories.

Main Contribution

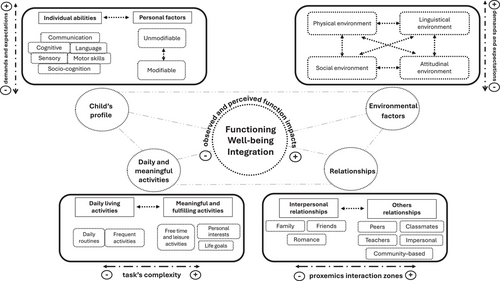

There is notable variability in the terminology used to describe functional impact and functional impairment, as well as ambiguity surrounding their respective meanings. Using an iterative lexicographical approach, we established operational definitions, distinguishing between two subcategories of functional consequences: observed and perceived functional impacts. This conceptual distinction enhances the clarity and applicability of these constructs in both research and clinical settings. Furthermore, five major categories were identified to guide the assessment of the functional impacts: individual abilities, personal factors, daily and meaningful activities, social relationships and environmental factors. Each category encompasses a range of dimensions and indicators. Based on these findings, we propose a structured and integrated framework: the Observed and Perceived Functional Impacts (OPFI) model for assessing functional consequences.

Conclusions and implications

Distinguishing between observed and perceived functional impacts provides a clearer and more comprehensive understanding of children's needs. This differentiation supports more targeted and effective clinical recommendations aimed at enhancing their communication skills, daily and meaningful activities, social relationships and overall quality of life. The proposed theoretical framework offers a clear conceptual framework for speech-language pathologists and other healthcare and educational professionals in shaping evaluation and intervention practices. This framework could be used to develop assessment tools aimed at assessing children's real-life functioning.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

- DLD and SLD significantly affect children's daily lives, particularly communication, social relationships and academic success. To design interventions tailored to each child's needs, it is crucial to accurately understand and measure these impacts effectively. However, the current terminology used to describe these impacts and the available assessment methods vary widely, leading to uncertainties about what should be evaluated for clinicians.

- The scoping review results allow us to disentangle the concepts of ‘observed’ and ‘perceived’ functional impacts of language and learning disorders by providing explicit definitions of these two concepts. Key dimensions and indicators were identified for both observed and perceived functional impacts. We propose a structured model based on these dimensions and indicators: Observed and Perceived Functional Impacts (OPFI) model. Considering its dynamic nature, this model will facilitate a more systematic assessment of the functional consequences for children with language or learning disorders.

- Given the limitations of standardised tests, enhancing speech-language assessments by integrating observations from parents, teachers, and other professionals is essential to comprehensively understand the child's strengths, challenges and needs. Focusing on the functional impacts of disorders—such as social interaction, daily activities and adaptation to school and family environments—refines intervention plans adapted to the child's specific needs and enables more precise monitoring of their progress. Including the child's perspective from an early age through well-suited self-report questionnaires or open-ended questions during clinical interviews supports a better understanding of their experiences and perceptions of the disorder.

1 Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders, such as Developmental Language Disorders (DLD), Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), significantly impact individuals’ quality of life, particularly in terms of social participation, education, and interpersonal relationships (American Psychiatric Association (APA) et al. 2015; Des Portes 2020). DLD is characterised by persistent difficulties in the acquisition and use of language due to impairments in comprehension and/or production in the absence of an underlying condition such as hearing impairment or intellectual disabilities (Bishop et al. 2017), while SLD encompasses challenges in specific academic skills such as reading, writing, or mathematics, despite adequate intelligence and opportunity (APA et al. 2015). Neurodevelopmental disorders can co-occur and often present overlapping features, complicating both diagnosis and intervention (Adlof and Hogan 2018; Kuiack and Archibald 2024). In the context of DLD, Bishop et al.’s seminal works through the Catalise consensus (Bishop et al. 2016, Bishop et al. 2017) marked a pivotal shift by establishing the necessity of assessing functional impairment in everyday life, a perspective that has since influenced clinical guidelines. For example, since 2018, the Ordre des Orthophonistes et Audiologistes du Québec (OOAQ) (2018) has encouraged its members to incorporate functional impact assessments into their practice. Before this initiative, the concepts of ‘functional impairment’ or ‘clinical significance’ remained somewhat peripheral to the diagnostic process.

Although Bishop et al. highlighted the need to further explore this critical aspect (Bishop et al. 2016, Bishop et al. 2017), Kulkarni et al. (2022) did not identify it as one of the ten key research gaps identified through a national priority-setting exercise, conducted through consultations with researchers, stakeholders and patients. This omission is noteworthy, particularly given the ongoing challenges stemming from the lack of a unified definition of functional impacts in DLD. Indeed, existing transdisciplinary theoretical frameworks offer multiple—and sometimes conflicting—interpretations of what constitutes ‘functional impairment’ and ‘functional impact,’ making conceptual alignment and practical application difficult (Maillart et al. 2024; Waine et al. 2023). Furthermore, Waine and colleagues called for greater conceptual clarity around the notion of ‘functional impact’ and ‘functional impairment’, noting that the ‘term functional may have a multifaceted meaning in clinical practice’ (Waine et al. 2023, p.16). They urged to identify which dimensions are truly relevant for understanding functional impact and how these can be measured objectively.

Currently, two major classification systems are available to both clinicians and researchers in rehabilitation sciences for documenting and explaining the causes and consequences of disorders, as well as other factors that influence the accomplishment of daily activities: the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; World Health Organization [WHO], 2007) and the Human Development Model—Disability Creation Process (HDM-DCP2; Fougeyrollas et al. 2018).

The ICF is widely adopted internationally as a comprehensive framework for assessing functioning and disability. It encompasses functional impairments in body functions and structures, limitations in activities, and restrictions on social participation, while also accounting for contextual factors (both personal and environmental). This framework has been instrumental in reshaping assessment and intervention approaches for children with speech, language and communication disorders (Cunningham et al. 2017; McGregor et al. 2023; McLeod and Bleile 2004; McLeod and Threats 2008; Westby and Washington 2017). The ICF framework asserts that functioning is not solely dependent on a diagnosis or the presence of ‘functional impairment’. In this paper, we follow Waine et al. (2023) interpretations of the WHO's model (2007): ‘functional impairments’ are problems in body function, such as significant deviations or losses, emerging through complex interactions between individual capacities and environmental influences. In speech-language pathology. Nevertheless, the application of the WHO's model has been interpreted in various ways (Waine et al. 2023). Indeed, it does not explicitly clarify how functional impairments translate into functional impact, nor how they interact with contextual factors. Rather, the ICF prioritises the independent assessment of functional limitations (i.e., restrictions in social participation and limitations in activities) within specific contexts (Gold 2014). This emphasis has fuelled ongoing debates regarding the most appropriate methods to operationalise ICF concepts within speech and language pathology.

The HDM-DCP2, is widely used in French-speaking countries. It emphasises the dynamic interplay between life habits (daily activities or social roles valued by the individual or their socio-cultural context), personal factors, and environmental influences. This model shares conceptual similarities with the ICF by framing disability as a result of interactions between an individual's capacities and environmental demands, aligning with a social and ecological perspective on disability (Barnes 2016). However, both models present limitations in their applicability to neurodevelopmental disorders. For instance, clinicians and researchers often interpret the concepts of activities and social participation differently within the ICF (Kwok et al. 2023). Additionally, the HDM-DCP2 does not explicitly distinguish between deficits intrinsic to the disorder (e.g., difficulty understanding complex sentences) and the consequences of the disorder (e.g., struggling to follow instructions in class).

Despite the recognition of environmental factors in these frameworks, there is a lack of assessment tools that adequately capture the interaction between individual abilities and contextual influences shaping disorder manifestations (Weiss et al. 2018). As Breault (2023) emphasises, the reciprocal relationship between individual and contextual factors is crucial for a child's development. For instance, a child with DLD may function very well in a supportive environment, which supports language intervention efficacy, contrary to a situation where there is no accommodation for the child's language needs. The lack of uniformity across clinicians and researchers complicates communication between professionals and restricts cross-study comparability (Fulcher-Rood et al. 2019; Kwok et al. 2023; Waine et al. 2023). Indeed, conceptual and methodological discrepancies impact how professionals assess patient needs, set goals, and measure intervention outcomes. Addressing these issues requires clearer distinctions between intrinsic deficits and their impacts, alongside the development of tools that better integrate individual abilities and environmental factors.

The overall aim of the present scoping review was to describe and clarify the identification and assessment of functional impacts for school-aged children with DLD and SLD. We aimed to achieve the following objectives: (1) Document how the concepts related to functional impacts and functional impairment are mentioned; (2) Identify existing definitions or descriptions of these concepts; (3) Propose a classification system based on the dimensions and indicators identified in the literature; and (4) Identify knowledge gaps.

2 Methods

The search was conducted in accordance with the framework established by Arksey and O'Malley (2005), recent recommendations for scoping reviews (Pollock et al. 2023) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) methodology (Tricco et al. 2018). Given the complexity and evolving nature of the literature on functional impacts in DLD and SLD, for the study identification stage, we followed a three-step methodology involving several iterations to refine the strategy (Aromataris and Riitano 2014; Khalil et al. 2016). The research team met regularly to discuss each stage of the review, as recommended by Pollock et al. (2023).

2.1 Stage 1: Research Question

Following Peters et al. (2020), our research question is: How are functional impacts and impairments (Concept) of school-aged children (Context) at risk of or diagnosed with DLD or SLD (Population) defined and measured?

2.2 Stage 2: Study Identification

- Step 1: Examination of MeSH terms

- Initially, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were examined to identify relevant keywords. However, no MeSH term specifically related to functional impacts or impairments was found.

- Step 2: Development of keywords

- The first author (JP) developed a list of keywords based on commonly used terminology amongst speech-language pathologists and researchers. Keywords were selected in both English and French.

- Step 3: Refinement through preliminary exploration

- An initial search was conducted across three databases (PubMed, ERIC and PsycINFO) for studies published between January 2013 and June 2023, applying the ‘school age (6–12 years)’ filter when available. The final list of keywords was refined in collaboration with the second author (MP) based on the results of this preliminary search.

2.3 Stage 3: Study Selection

We conducted our search for the period between January 2013 and November 2023 across six databases (CINAHL, ERIC, Psychology & Behavioural Science Collection and Education Source), using the final set of keywords (see Appendix 1).

2.3.1 Title/Abstract (TiAb) Screening

The first author developed an initial list of inclusion and exclusion criteria, which was then tested in a preliminary phase using a random sample of 10 titles and abstracts. This sample was independently assessed by two authors (JP and MP). When a title or abstract did not provide sufficient information to make a definitive inclusion or exclusion decision, the study was retained for full-text screening. The initial screening resulted in a 70% agreement rate between the two authors. After comparing their decisions, they identified discrepancies related to the interpretation and application of the PCC framework (Population, Concept, Context). As a result, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were revised to include clearer definitions of target populations and eligible concepts, notably individual skills. A second random sample, representing 10% of the total set of titles and abstracts, was then independently assessed by the same two authors, yielding a 100% agreement rate.

Subsequently, the first author screened all titles and abstracts using the final list of criteria (Table 1), which was documented in an Excel document. Any ambiguities (n = 22) were discussed and resolved with the second author. Titles/abstracts written in languages other than French and English were included if they could be translated using an automatic translation software (Google Translate, and if necessary, DeepL). This translation process was applied to 31 articles (4 in German, 9 in Arabic, 8 in Spanish, 4 in Italian, 2 in Portuguese, 1 in Polish and 3 in Turkish) to ensure broader inclusion of available studies and minimise language bias.

| PCC | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Concept |

|

|

| Context |

|

|

To assess inter-rater reliability during the title–abstract screening phase (Belur et al. 2021), a random sample of 220 titles and abstracts (20% of the total) was independently reviewed by the lead author and two 3rd-year speech-therapy students. Each student reviewed 10% of the sample. Agreement was initially calculated as a percentage, followed by Cohen's kappa, using Jamovi software (The Jamovi Project 2.4.11, 2023).

2.3.2 Full-Text Screening

The first author performed a full-text screening of all titles/abstracts selected. Four documents (two in German, one in Spanish and one in Polish) were translated using automatic translation software (Google Translate, and if necessary, DeepL or ChatGPT) and five documents were excluded, as they were not available in electronic format. Any ambiguities have been discussed and resolved with the second author (MP). During this phase, a manual search of the reference lists of selected articles was conducted to identify additional relevant studies. This process led to the inclusion of six additional articles not found in the initial search.

Of the 1094 records initially screened at the title and abstract level, 97 were selected for full-text review, of which 53 met the inclusion criteria. To assess inter-rater reliability during the full-text screening phase (Belur et al. 2021), a random sample of 12 full-text articles—representing approximately 23% (12/53) of the included articles—was independently assessed by a second member of the research team. The distribution was as follows: six articles by MP, three by DC and three by NMP. A percentage agreement was calculated for each reviewer.

2.4 Stage 4: Data Extraction

During the data extraction stage, the following information were documented in a second Excel document, which was developed by the research team: general study details (author, title, year of publication, study location, methodology), specific study data (objective, population, measurement instruments used) and results (terminology or dimensions/indicators). In studies that included data on children with language and/or learning disorders alongside other groups (such as children with ADHD and ASD), only data related to the DLD and SLD groups were extracted. Data extraction was carried out by the first author. Instead of a reliability check, the first author has consulted the second or third author in case of uncertainty.

2.5 Stage 5A: Collating, Summarising and Reporting the Results

The included studies were systematically summarised in an Excel file, capturing key details such as study location, terminology related to functional impacts, and identified dimensions and indicators. The process began by listing terms related to functional impacts or impairments, along with their formal definitions or inferred meanings from the texts. A lexicographical analysis was conducted to explore usage frequency and semantic variations, helping identify common meanings, discrepancies and potential gaps in the literature.

A qualitative inductive approach (Elo and Kyngäs 2008) was then applied through an iterative process to identify dimension indicators from the literature. Initially, a deductive approach was attempted, aiming to categorise dimensions and indicators based on models like the ICF and HDM-DCP2. However, challenges arose due to the overlap and ambiguity of certain complex indicators, as noted by Kwok et al. (2023) in their critique of the ICF. For example, in the ICF model, social interactions are categorised either under participation (social engagement) or activity (competence in interactions), while the HDM-DCP2 model could categorise them under life habits, which are influenced by a combination of contextual factors and individual capabilities but are largely shaped by environmental factors. This difference in approach between the two models created confusion, as it was not always clear how to categorise social interactions in a way that reflected their complexity. Additionally, in the ICF model, language can be classified as a body function (physiological abilities), an activity (functional competence), or under participation (its influence on social engagement), whereas the HDM-DCP2 model views language as a skill shaped by both environmental and social factors, with a significant emphasis on the role of contextual influences. This variability further highlights the need for a more refined system that integrates individual, social and environmental influences, offering a clearer and more comprehensive framework for understanding functional impacts of neurodevelopmental disorders.

2.6 Stage 5B: Development of a New Classification System

To address the issues related to the classification of the indicators, the multidisciplinary research team—comprising two speech and language pathologists, one psychologist and one linguist—developed a new classification system, which refined existing categories to better reflect the multidimensional nature of functional impacts. This new classification system (see Table 2) integrates insights from Kwok et al. (2023) and Waine et al. (2023) to propose a more comprehensive framework for both clinical and research applications, capturing functional impacts across individual, social and environmental domains in neurodevelopmental disorders. To clarify the terminology used throughout this article, the term ‘functional consequences’ refers to an overarching concept that encompasses both ‘observed and perceived functional impacts’ —denoting, respectively, objectively measurable effects on functioning and individuals' subjective experiences of those effects. Furthermore, to address conceptual ambiguities and enhance the clarity of classification, the research team also refined and reorganised existing model categories from ICF and HDM-DCP2. Notably, Individual abilities were introduced as a distinct category, and Daily living and meaningful activities were used in place of the more general Activities and Participation, thereby highlighting the subjective significance of everyday tasks.

| ICF | HDM-DCP2 | New categories |

|---|---|---|

| Personal factors | Personal factors | Personal factors |

| Environmental factors | Environmental factors | Environmental factors |

| Body structures and function impairments | Personal factors | Individual abilities |

| Participation | Social Roles (life habits) | Relationships |

| Activities | Current activities (life habits) | Daily living and meaningful activities |

The last phase of the development process involved a deductive approach (Elo and Kyngäs 2008) used to organise the identified dimensions and indicators into five overarching categories: individual abilities, personal factors, daily and meaningful activities, relationships and environmental factors.

3 Results

3.1 Selection of the Sources of Evidence

3.1.1 Included Studies

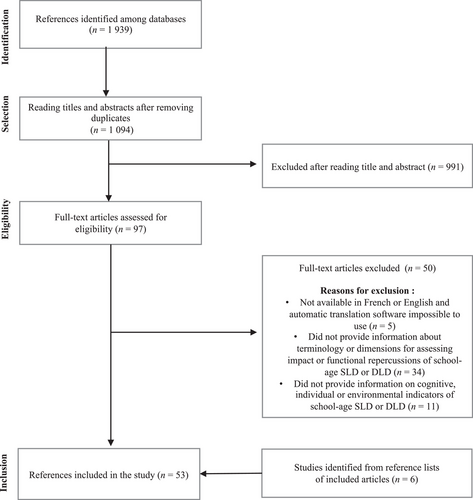

The literature search identified 1939 documents from the six databases, and 11 additional documents were identified from the reference lists of the selected articles. Of these, 97 full texts were read, leading to the inclusion of 53 documents for data extraction (see Appendix 2). A diagram outlining the study selection process is provided in Figure 1.

3.1.2 Inter-Rater Reliability

We assessed inter-rater reliability (IRR) using Cohen's kappa, based on McHugh's (2012) interpretation: 0–0.20 = none, 0.21–0.39 = minimal, 0.40–0.59 = weak, 0.60–0.79 = moderate, 0.80–0.90 = strong and >0.90 = almost perfect.

During the title and abstract screening phase, Student A demonstrated moderate agreement (96%; κ = 0.70, p < 0.001) with the researcher, while agreement with Student B was weak (90%; κ = 0.434, p < 0.001). Disagreements and uncertainties (n = 12) were discussed in a debriefing session aimed at clarifying the criteria, which led to classification changes. Updated IRRs showed improvement: moderate agreement was achieved with both Student A (99%; κ = 0.73, p < 0.001) and Student B (95%; κ = 0.722, p < 0.001).

Although per cent agreement was high, kappa values remained moderate, likely due to the imbalanced distribution of coding decisions (i.e., predominance of ‘Exclude’ judgments), a situation known to affect κ reliability. This imbalance is known to affect the reliability of κ, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as the ‘kappa paradox’ (Cicchetti and Feinstein 1990; Gwet 2008). The paradox describes situations in which κ appears low despite high agreement, due to skewed distributions and minimal disagreement (Belur et al., 2021). In such contexts, per cent agreement may serve as a complementary measure of inter-rater reliability—particularly when coders are well-trained and the likelihood of guessing is minimal (McHugh 2012).

In the full-text selection phase, overall agreement was 91.6% (11/12). Pairwise agreement was 100% (6/6) between Authors 1 and 2, 100% (3/3) between Authors 1 and 3, and 66% (2/3) between Authors 1 and 4. Due to the small sample sizes, no additional IRR analyses were performed for these rater pairs.

3.1.3 Document Characteristics

Amongst the 53 selected documents, there was one thesis, one book chapter and 51 articles published in 33 different scientific journals (the two most frequent being the International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders and the Research in Developmental Disabilities).

3.2 Assessment of Functional Impacts and Functional Impairment: Terminology and Dimensions

The key findings of our scoping review presented the main terminological concepts, dimensions, indicators and trends in the literature regarding the functional consequences of DLD and SLD in school-aged children.

3.2.1 Terminology Used

Amongst the 53 documents, 20 included a concept that could be related to functional consequences of DLD and SLD (Backenson et al. 2015; Bishop et al. 2016, 2017; Bradbury et al. 2021; Calder et al. 2023, 2024; Duff et al. 2023; Eadie et al. 2018; Fisher et al. 2019; Gough Kenyon et al. 2022; Helland and Helland 2017; Jacob and Maintenant 2017; Miller et al. 2013; McGregor 2020; McGregor et al. 2020, 2023; Reilly et al. 2014; Stipanicic et al. 2016; Waine et al. 2023; Westby and Washington 2017). However, none of the authors precisely defined the concepts or realities they encompass. There were 221 mentions of the concept distributed across 24 different terms. The terms ‘functional impact’, ‘functional limitation’ and ‘functional impairment’ were the most frequently mentioned, with 55, 48 and 29 mentions respectively (Table 3). While these terms are generally used to describe distinct concepts, they are sometimes used interchangeably. Therefore, the meanings provided in the following section are based on contextual interpretations of how these terms appear in the included studies, rather than on universally agreed-upon definitions. This variability in terminology across disciplines and geographic regions suggests a lack of conceptual clarity in the field.

| Terminology used | Number of occurrences (n = 221) | Number of sources (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Functional impact | 55 (25%) | 11 |

| Functional limitation | 48 (22%) | 1 |

| Functional impairment | 29 (13%) | 5 |

| Functional limitations | 26 (12%) | 5 |

| Functional complexity | 12 (5%) | 1 |

| Functional impacts | 11 (5 %) | 3 |

| Functional outcomes | 10 (5%) | 8 |

| Functional impairments | 5 (2%) | 4 |

| Functional difficulties | 3 (1%) | 2 |

| Functional challenges | 2 (1%) | 2 |

| Functional outcome | 2 (1%) | 2 |

| Functional problems | 2 (1%) | 2 |

| Functional weaknesses and disabilities | 2 (1%) | 1 |

| Functional communication outcomes | 2 (1%) | 1 |

| Functional deficits | 2 (1%) | 2 |

| Impact fonctionnel | 2 (1%) | 2 |

| Functional consequence | 1 (<1%) | 1 |

| Functional consequences | 1 (<1%) | 1 |

| Functional communication difficulties | 1 (<1%) | 1 |

| Functional disabilities | 1 (<1%) | 1 |

| Functional strengths and weaknesses | 1 (<1%) | 1 |

| Functional and educational impact | 1 (<1%) | 1 |

| functional disabilities or weaknesses | 1 (<1%) | 1 |

| Functional strengths and needs | 1 (<1%) | 1 |

3.2.2 Meanings of Key Terms

The term ‘functional impact’ is widely used (n = 55; 25%) to describe the consequences of DLD and SLD on daily life. It generally refers to difficulties that hinder individuals from carrying out daily activities or building social relationships (Bishop et al. 2016; McGregor et al. 2020; Waine et al. 2023). However, there is considerable variability in its definition. Amongst the 11 documents using this term (Bishop et al. 2016; Calder et al. 2023, 2024; Duff et al. 2023; Eadie et al. 2018; Fisher et al. 2019; Gough Kenyon et al. 2022; McGregor 2020; McGregor et al. 2020; Reilly et al. 2014; Waine et al. 2023), some authors consider it to encompass all the effects on an individual's daily activities and social participation (Waine et al. 2023), while others broaden this definition to include various psychosocial factors such as socio-educational and socio-emotional aspects (McGregor 2020), behavioural issues (Calder et al. 2024), and quality of life (Eadie et al. 2018; Waine et al. 2023), following WHO (2007) concepts, define ‘functional impact’ as ‘difficulties in executing activities and/or problems experienced in involvement in life situations’.

The term ‘functional limitation’ (n = 48; 22%) appears in only one source (Miller et al., 2013), indicating a more targeted and less widespread use in the documents screened. It is defined as ‘the negative or deficient aspects of a child's functional status, whether related to physiological aspects or daily activities’ (p. 2).

Finally, the term ‘functional impairment’ (n = 29; 13%) is used in five documents (Bishop et al. 2016, 2017; Miller et al. 2013; Gough Kenyon et al. 2022; Reilly et al. 2014), though it is rarely clearly defined. One exception is Bishop et al. (2017), which describes it as functional limitations in daily life. Waine et al. (2023) used a more specific formulation, namely ‘functional language impairments’.

3.2.3 Development of a New Classification System

Despite their numerical abundance, many of these indicators referred to similar underlying constructs, albeit with considerable terminological variability. For example, within the relationships category, 17 separate indicators were identified, including peer relationships, peer interactions, peer conflicts, conflict resolution with peers, relationships with parents, conflicts with parents, relationships with siblings, conflicts with siblings, amongst others. Due to conceptual overlap and the interchangeable use of terms across sources, these indicators were consolidated into six leading indicators. Both frequently reported indicators (e.g., peer relationships, cited across multiple sources) and more specific or less frequently mentioned ones (e.g., social functioning, cited only once) were retained in the classification system when conceptually relevant.

The final proposed framework (see Table 2) seeks to account for both observed and perceived functional impacts across individual, social and environmental domains in the context of neurodevelopmental disorders. This deductive phase involved organising the previously identified dimensions and indicators into five overarching conceptual categories: individual abilities, personal factors, daily and meaningful activities, social relationships and environmental factors. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 4, which provides detailed descriptions of the main dimensions and indicators.

| Dimensions and leading indicators identified | Sources |

|---|---|

Individual abilities (5 indicators)

|

Backenson et al. (2015); Baldi et al. (2018); Blanchet and Assaiante (2022); Calder et al. (2023); Chieffo et al. (2023); Crish (2022); Cuperus et al. (2014); Curtis et al. (2018); Finlay and McPhillips (2013); Fisher et al. (2019); Flapper and Schoemaker (2013); Hsu et Bishop (2014); Ibáñez-Rodríguez et al. (2021); Jacob and Maintenant (2017); Kuusisto et al. (2017); McGregor et al. (2023); Miller et al. (2013); Mok et al. (2014); Nachshon and Horowitz-Kraus (2019); Nicola and Watter (2015); Norbury et al. (2017); Ottosson et al. (2022); Pauls and Archibald (2016); St Clair et al. (2019); Stipanicic et al. (2016); Suhaili et al. (2019); Tseng and Hsu (2023) |

Personal factors (18 indicators)

|

Baldi et al. (2018); Bishop et al. (2017); Blanchet and Assaiante (2022); Chan et al. (2019); Cuperus et al. (2014); Duff et al. (2023); Eadie et al. (2018); Flapper and Schoemaker (2013); Haythorne et al. (2022); Kuusisto et al. (2017); Lin et al. (2022); Lyons and Soultone (2018); McGregor et al. (2023); Nielsen et al. (2018); Norbury et al. (2017) |

Daily and meaningful activities (8 indicators)

|

Bakopoulou and Dockrell (2016); Biotteau et al. (2017); Chan et al. (2019); Chieffo et al. (2023); Curtis et al. (2018); Eadie et al. (2018); Gough Kenyon et al. (2022); Helland and Helland (2017); Huang et al. (2020); Ibáñez-Rodríguez et al. (2021); Lyons and Soultone (2018); Mackie and Law (2014); McGregor (2020); McGregor et al. (2023); Mok et al. (2014); Nachshon and Horowitz-Kraus (2019); Nielsen et al. (2018); Singer et al. (2023); St Clair et al. (2019) |

Relationships (5 indicators)

|

Bishop et al. (2017); Chan et al. (2019); Eadie et al. (2018); Flapper and Schoemaker (2013); Gough Kenyon et al. (2022); Huang et al. (2020); Ibáñez-Rodríguez et al. (2021); Jacob and Maintenant (2017); Lyons and Soultone (2018); Mackie and Law (2014); McGregor et al. (2023); Mok et al. (2014); Nicola and Watter (2015); St Clair et al. (2019) |

Environmental factors (10 indicators)

|

Bagnato (2017); Bruce and Hansson (2019); Duff et al. (2023); Haythorne et al. (2022); Huang et al. (2020); Mackie and Law (2014); McGregor et al. (2023); Robinson and Young (2019); Singer et al. (2023); St Clair et al. (2019) |

- a “Modifiable personal factors” refer to individual characteristics or conditions that can be influenced or changed through intervention or external support.

- b “Unmodifiable personal factors” are those individual characteristics or conditions that cannot be altered, such as genetic traits or chronic conditions.

3.2.3.1 Individual Abilities

The WHO (2007, p. 15) describes individual abilities as ‘features of the individual that are not part of the health condition’. This category is most commonly assessed through standardised tests, parent questionnaires, or clinical observations that measure a child's skills. However, these assessments do not always accurately reflect the child's real-life performance (Calder et al. 2024). These processes are often identified as key indicators when evaluating children with language or learning disorders. The five most frequently cited indicators in the 25 studies on this dimension include cognitive, motor, language, communication, social-emotional and social cognition.

3.2.3.2 Personal Factors

Personal factors correspond to intrinsic characteristics of the child that influence how they perceive their environment, respond to challenges, and adapt to various daily situations. Amongst the 20 studies, 18 main indicators were identified and classified as follows: adaptive behaviours, age, avoidance strategies, conduct problems, co-occurring disorders, externalising behavioural disorders, sex /gender, hyperactivity, inattention, internalising behavioural disorders, low self-esteem, negative emotions, physical health, self-concept, self-awareness, stress, temperament. Amongst these, sex/gender and prosocial behaviours were the most frequently reported, each in nine studies; sex and gender were often used interchangeably and are therefore treated as a single indicator. Definitions and classifications of personal factors vary significantly across studies. Westby and Washington (2017), Cunningham et al. (2017) and Singer et al. (2023) all highlighted the absence of a clearly defined list of personal factors within the ICF framework. Their work points to diverse emphases—ranging from cultural and ethnic contexts to health conditions, coping styles and specific cognitive or socio-emotional abilities. Biotteau et al. (2017) also stressed the frequent co-occurrence of neurodevelopmental disorders. This variability underscores both the conceptual breadth and the inconsistencies that remain in the operationalisation of personal factors across the literature.

3.2.3.3 Daily and Meaningful Activities

Daily and meaningful activities refer to the tasks or actions that individuals engage in regularly, encompassing both activities of daily living (such as eating, dressing and grooming) and those that contribute to personal well-being, relationships and overall life satisfaction. Fourteen references reported indicators related to these components, including academic or school activities, leisure and recreational pursuits, sports, household tasks (e.g., following instructions, preparing snacks, completing chores, locking the front door, managing a budget, using transportation) and life habits (e.g., sleep and nutrition).

A recurring concern in the literature is the child's dependence on adults and limited autonomy, which are seen as significant issues when assessing the functional impacts of DLD and SLD. These activities are consistently described as essential for a child's development, autonomy and quality of life (Eadie et al. 2018; Flapper and Schoemaker 2013; Ottosson et al. 2022).

More specifically, life habits related to sleep and nutrition appear to be affected in children at risk of DLD (St Clair et al. 2019). Similar findings have been reported regarding sleep difficulties in children with DLD (Chan et al. 2019; Nicola and Watter 2015). Despite these converging results, none of the other 52 documents analysed examined potential associations between language disorders and eating problems, thereby highlighting a notable gap in the current literature.

3.2.3.4 Relationships

Relationships encompass interpersonal relationships (family, friends) and other social relationships (including intimate and group-based social interactions). Across the 14 studies analysed, several factors were identified as central to shaping a child's social network, quality of life and socio-emotional development (Eadie et al. 2018; Jacob and Maintenant 2017; Lyons and Soultone 2018; Mok et al. 2014; St Clair et al. 2019). These include family dynamics (e.g., interactions with parents and siblings), friendship patterns (e.g., the number and stability of friendships), school-based relationships (e.g., connections with classmates and teachers) and broader social engagements (e.g., peer interactions in various contexts). Communication breakdowns—within family, school, or peer settings—can profoundly affect these relationships' quality, durability, frequency and stability. Both quality of interactions, frequency of interactions and communications breakdowns are frequently cited indicators in the literature (Chan et al. 2019; Eadie et al. 2018; Gough Kenyon et al. 2022; Ibáñez-Rodríguez et al. 2021; Jacob and Maintenant 2017; Lyons and Soultone 2018). Consequently, it is essential to incorporate these interactional parameters when assessing the functional impacts of communication challenges. For instance, the ability to form and sustain long-term friendships is highlighted as a critical metric in 4 of the 14 studies (Gough Kenyon et al. 2022; Ibáñez-Rodríguez et al. 2021; Jacob and Maintenant 2017; Lyons and Soultone 2018).

3.2.3.5 Environmental Factors

Environmental factors comprise the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives (WHO 2007). Amongst the 10 documents analysed, 10 leading indicators were identified: additional educational services, access to services, education adjustments, external support (family, peers, friends, teachers, other persons), family characteristics (parental distress, exposure to maltreatment, family stress, socioeconomic status, socio-cultural status, caregiver educational attainment, family size), implicit and explicit attitudes of communication partners (implicit and explicit attitudes of communication partners, perceptions of communication partners, impatience, stigma, mockery, peer rejection and family conflicts), linguistic environment (early language communication environment, linguistic status), parental concerns (academic achievement), physical environment (noise), receiving an intervention. Regarding linguistic status, one document classified this indicator as a personal factor (Singer et al. 2023), associating it with the child's prosocial behaviours. However, one other document underscored the significant role of the linguistic context (whether monolingual or multilingual) in shaping communicative opportunities, social interactions and learning experiences, as these factors can significantly enhance communicative participation and foster prosocial behaviours over time (Cunningham et al. 2017).

3.2.4 Knowledge Gaps in the Current Literature

Despite significant advances in understanding neurodevelopmental disorders and their functional impacts, several critical gaps remain in the literature. One of the main challenges is the lack of a unified framework for assessing the functional consequences of these disorders. While many studies focus on symptomatology and diagnostic criteria, few offer a comprehensive examination of how these disorders affect individuals' daily lives, relationships and overall well-being in a multidimensional manner. Furthermore, existing research often fails to integrate a theoretical framework, such as the ICF or HDM-DCP2, which complicates the comparison of findings and the application of interventions across disciplines. Another key gap is the limited exploration of the role of personal and environmental factors—such as gender, family support and educational accommodations—in shaping the functional outcomes of individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Additionally, while some studies address functional impairment, none explicitly distinguish between observed and perceived impacts, which limits our understanding of how individuals personally experience their conditions.

4 DISCUSSION

This scoping review aimed to describe and clarify the identification and assessment of functional impacts for school-aged children with DLD and SLD. Specifically, the objectives were to: (1) Document how the concepts related to functional impacts and functional impairment are mentioned; (2) Identify existing definitions or descriptions of these concepts; (3) Propose a classification system based on the dimensions and indicators identified in the literature; and (4) Identify knowledge gaps.

The evolution in conceptualising functional impacts, guided by Bishop et al. 2016, 2017, reflects a shift toward a biopsychosocial perspective, aligning with frameworks like the ICF, HDM-DCP2. These frameworks incorporate individual abilities, activities, participation, personal factors and environmental influences in evaluating functional impacts. However, the variability in definitions across these models complicates interdisciplinary collaboration and research comparability. Our findings reveal significant ambiguities in the terms ‘functional impairment’ and ‘functional impact’, which are often conflated with broader concepts like ‘disability’ or ‘deficit’. As Maillart et al. (2024) noted, defining functional impacts precisely remains challenging. To address these issues, we propose a new conceptual framework (the Observed and Perceived Functional Impacts [OPFI] model) with updated definitions and a model aimed at harmonising and clarifying the understanding and application of these terms. While the proposed model is informed by existing frameworks—notably the ICF and HDM-DCP2—and the terminology from Waine et al. (2023), it does not strictly adhere to any of these references. Instead, it integrates elements from these and other sources.

4.1 Terminology: Disentangling Functional Impacts and Functional Impairment

The results of the lexicographic analysis revealed significant terminological variability and interchangeability across the 53 selected studies, along with notable inconsistencies, overlaps and gaps—largely attributable to underlying conceptual divergences. In this context, we deliberately chose not to retain the terms functional limitations and functional impairment when defining functional impacts or consequences. These terms are often rooted in a biomedical perspective focused on deficits and aligned with ableist frameworks (Bottema-Beutel et al. 2024; Timmons et al. 2024), which fail to sufficiently consider the personal and environmental factors that shape functional experiences in daily life. Moreover, as Waine et al. (2023) emphasise, the lack of clear definitions and detailed descriptions of the associated dimensions in the literature highlights the urgent need to reach consensus on a shared conceptual framework by providing clear definitions and listing the relevant indicators. This observation guided us in developing operational definitions that better align with contemporary recommendations.

Following this, an iterative lexicographical approach was employed to refine the initial definitions. This process involved multiple rounds of feedback from the research team, allowing for continuous revisions and improvements. Through this iterative process, the definitions were progressively refined, incorporating insights from ongoing discussions within the research team to ensure greater accuracy and clarity.

The final definitions include two interrelated concepts: ‘observed functional impacts’ (Essers et al. 2019; Feuering et al. 2014), which refer to the observable consequences of the disorder, and ‘perceived functional impacts’ (Essers et al. 2019; Feuering et al. 2014; Kaim et al. 2024; Martyr et al. 2019; Schütz et al. 2023; Serrano et al. 2022; Svensson et al. 2021), which pertain to the individual's subjective and personal experience. These concepts were refined through multiple rounds of discussion, ultimately reaching consensus. The distinction between observed and perceived functional impacts (Table 5) offers a more nuanced understanding of functional consequences.

| Concept | Definitions | Supplementary comments |

|---|---|---|

| Observed functional impacts (in French: "impacts fonctionnels") | Observable consequences of the disorder on an individual's ability to perform daily activities or engage in social situations. These impacts vary depending on the context and the demands of the environment (e.g. school, home, leisure club) and may evolve. | "Observed functional impacts" can be observed and measured by the patient himself or by a third party (parent, teacher, or another significant person in the child's life) and manifest as limitations in task execution or restrictions in social engagement in response to environmental demands. For example, an individual may observe that they are partially capable of taking a bus alone to an unfamiliar destination, provided they have been prepared with the exact amount of money for the ticket. |

| Perceived functional impacts (in French: "retentissements fonctionnels") | Individual's subjective and personal experience of a disorder, including the resulting emotional and behavioural consequences. They encompass the perception, interpretation, and daily experience of limitations and restrictions, influencing the individual's feelings and strategies to adapt to these challenges. | These subjective perceptions encompass emotional reactions (e.g., frustration, anxiety, anger) and behavioural responses (e.g., avoidance, self-harm, aggression, and disobedience), which are influenced by personal and contextual factors. For instance, the need for assistance is less problematic when provided by a trusted person. However, it may be more challenging to accept when the assistance comes from an unfamiliar or less familiar individual. Additionally, perceived functional impacts extend beyond the individual and include the perceived functional impacts experienced by the parents. These impacts affect the parents' emotional and behavioural responses as they navigate the daily challenges of supporting their children. Parents may experience frustration, anxiety, or even feelings of helplessness, and their strategies for coping with these challenges are influenced by their perceptions of their child's limitations and needs. |

The term ‘functional consequences’ (in French: conséquences fonctionnelles) serves as an overarching concept that encompasses both observed and perceived functional impacts. It refers to all consequences of a disorder on an individual's ability to perform activities, engage in social interactions and maintain a satisfactory quality of life. This definition explicitly acknowledges the dynamic and context-dependent nature of these effects, as well as the abilities and coping strategies individuals employ in various environments, leading to temporal and situational variability in disability. As emphasised by Catts and Petscher (2022), functional consequences fluctuate across contexts and evolve over time, influenced by the interplay between risk factors (e.g., a stressful environment) and protective factors (e.g., appropriate support). This concept highlights that the functional impacts of a disorder are not static but can change depending on both external and internal factors, which is crucial for understanding the full scope of an individual's experience and for planning appropriate interventions.

4.2 Development of a New Conceptual Model

A new conceptual model is needed to better capture the complexity of how DLD and SLD affect children's lives. The first step is selecting core terminology to guide its use. Current models, which focus on normative comparisons, overlook adaptive strategies, individual variations and contextual differences that shape functional experiences. Our analysis suggests that the dimensions and indicators related to functional impacts would benefit from a more structured organisation. Grouping conceptually similar elements would clarify their use and enhance comparability across studies.

To address this need, we drew on the clinical expertise of the first author—a speech and language therapist with 7 years of experience working with school-aged children—and integrated insights from complementary research disciplines. This clinical expertise, recognised as one of the four foundational pillars of the Evidence-Based Practice framework (alongside scientific evidence, patient preferences and contextual factors), played a vital role in bridging empirical and experiential knowledge. By serving as a form of ‘grey literature’, it offered a nuanced perspective grounded in real-world interactions with children and families (Fissel Brannick et al. 2022; Greenwell and Walsh 2021; Sackett et al. 1996; Souza and Cáceres-Assenço 2024). Drawing from this combined approach, the research item identified logical groupings based on conceptual similarities amongst the dimensions and indicators. This process led to the development of a classification system structured around four domains and organised into five overarching categories, each comprising a range of dimensions and their associated indicators.

- Child's profile: This domain encompasses both the individual's abilities (e.g., cognitive, motor and linguistic skills) and the personal factors, which may be modifiable (e.g., motivation, resilience, self-esteem) or unmodifiable (e.g., age, temperament, sex/gender).

- Daily and meaningful activities: This domain focuses on how the disorder affects daily tasks (such as schoolwork and personal hygiene), recreational activities (such as hobbies) and an individual's meaningful engagement.

- Relationships: This domain explores the condition's impact on interpersonal relationships (including friendships, family relations and other social relationships such as participating in discussions or work groups and social play) and social roles (such as class representative, running errands for parents or oneself).

- Environmental factors: This domain addresses different aspects of the environment, notably attitudinal (such as attitudes and perceptions of the people who interact with the child), linguistic (such as the language context in which the child grows and the language of the society), physical (such as noise level, access to technological support, adapted environment) and social (such as cultural, religious, academic).

To better capture the unique nature of an individual's skills and competencies, which are directly related to their capacity to perform activities and participate in social roles, ‘individual abilities’ is proposed as a distinct category from ‘personal factors’. By making this distinction, the classification system can more clearly address how individual capacities influence functional outcomes, independently from the broader personal factors (e.g., personal background, context, or environmental influences) that may shape those outcomes. Similarly, ‘Daily and meaningful activities’ is proposed as a replacement for ‘Activities’ and ‘Participation’ to emphasise the personal significance of tasks. This distinction clarifies the difference between functional tasks that individuals engage in routinely (e.g., self-care or home management) and the more socially driven roles or relationships (e.g., participation in group activities or social networks). These elements are judged to have a different impact on an individual's life, reflecting respectively functional independence and social interaction.

These new categories emphasised how the interactions between these elements collectively shape the overall functional impacts of DLD and SLD. The OPFI model encourages a holistic, multidimensional understanding of children's challenges and a more personalised approach to assessing their challenges and needs.

The OPFI model was designed as a practical tool to help clinicians and researchers adopt a shared language and gradually standardised practices for assessing the functional impacts of DLD and SLD in both clinical settings and research. This simplified and structured approach makes the assessment process more effective by considering the various dimensions that influence these functional impacts. The model emphasises that each child has a unique developmental profile, which includes notably cognitive, language, social, sensory and motor skills. These profiles influence how children engage in daily or meaningful activities and form fulfilling relationships with others. Both observed and perceived functional impacts are shaped by intra-individual variability (the child's profile) and environmental factors, which influence their social functioning and overall well-being. The model highlights the importance of a supportive environment, such as family support, school accommodations and specialised services, which can reduce the perceived severity of the disorder and promote inclusion. It also emphasises the ‘compensatory or protective effect’ (Biotteau et al. 2017), where early interventions and inclusive environments foster brain plasticity and enhance abilities, improving quality of life. Additionally, balancing internal demands (personal aspirations) and external demands (social, familial and professional pressures) is crucial in enabling children to thrive while maintaining their well-being. For example, a child with language difficulties who excels in sports may develop athletic skills and strengthen social relationships, positively impacting broader social interactions and expectations in different environments. These dynamics contribute to fostering autonomy, self-esteem and meaningful engagement.

4.3 Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The search period, from January 2013 to November 2023, may exclude key studies published before or after these dates. Publication bias may also influence the review, as studies with positive results are more likely to be published, potentially skewing the available evidence. The absence of interrater reliability across all stages of the review, as recommended by Pollock et al. (2023), may affect the consistency of findings due to differing subjective interpretations between reviewers. Efforts were made to include diverse perspectives, but the review focused on a limited number of languages and excluded sources not translatable via software, potentially introducing linguistic and cultural bias. The use of translation software, while practical, may not fully capture semantic accuracy and cultural nuances, impacting the result interpretation.

Regarding the new classification system, while it aimed to capture significant aspects of daily and meaningful activities as well as social relationships, it may not fully encompass the diverse experiences of children with DLD and SLD, particularly in terms of sex/gender differences, personal factors and environmental influences. For instance, children in complex social or family contexts may face additional barriers not addressed by traditional assessments (Singer et al. 2023). Moreover, sex/gender differences were not sufficiently explored, although academic and societal expectations may influence how boys, often considered at risk—particularly those from low socio-economic status backgrounds—exhibit strengths and weaknesses in language and social behaviour, along with their compensatory strategies (Mackie and Law 2014; McGregor 2020; Singer et al. 2023). A secondary analysis is being conducted to explore this issue in greater detail. Additionally, personal factors such as motivation, self-determination, awareness of the disorder and environmental changes like relocation or parental separation are often overlooked, yet they are crucial for understanding how children adapt to these challenges. These personal and environmental influences may interact with linguistic factors, especially in bilingual and multilingual children, who face unique challenges, such as limited access to tailored interventions. These limitations highlight the need for more comprehensive research to better capture the complex, multifaceted nature of the functional impacts of DLD and SLD.

4.4 Research Implications and Applications

The OPFI model offers a comprehensive and multidimensional framework for evaluating the functional impacts of language disorders by integrating both perceived and observed consequences. It promotes a shift from deficit-focused assessments toward a contextualised understanding of how language difficulties interact with personal factors, daily and meaningful activities, social relationships and environmental factors.

With its structured and operationalizable system of clearly defined indicators, the OPFI model should facilitate the harmonisation of findings and contribute to increasing the comparability across studies using it. If used to support the development of specialised tools and guide clinical reasoning, it might help to target and individualise interventions. Additional research is required to confirm that.

Future research could build on the OPFI model through longitudinal studies to track changes in functional impacts over time. Such studies would support the identification of impacts during key developmental transitions, as well as risk and protective factors, and long-term intervention outcomes. Including both perceived and observed impacts would enhance understanding of adaptation processes and help refine models of functional impairment in everyday contexts.

4.5 Clinical Implications

Documenting the functional consequences of DLD and SLD—such as their impact on daily and meaningful activities, social relationships and academic performance—is now an integral part of the diagnosis, and used to assess the severity of the disorder, and facilitating access to specialised services (Bishop et al. 2017; OOAQ 2018). The OPFI model offers a structured framework for evaluating observed and perceived impacts, providing a holistic perspective that informs clinical decision-making and intervention planning. This approach emphasises three key aspects: identifying and diagnosing the disorder, facilitating the access to services tailored to the child's needs, and developing individualised intervention strategies promoting inclusion.

4.6 Identification and Diagnosis

Standardised tests are widely used in diagnosing neurodevelopmental disorders; however, their utility is limited when used in isolation to assess these disorders' severity or functional impacts. While effective for identifying certain aspects of a child's cognitive and language abilities, these tests often do not fully capture the complexity of a child's profile (Lancaster and Camarata 2019). They are not sufficiently sensitive to the real-world implications of DLD and SLD (Calder et al. 2024). Furthermore, standardised tests do not reliably reflect a child's performance in naturalistic settings (McGregor et al. 2023) and show low sensitivity to changes over time, limiting their effectiveness for longitudinal monitoring (Bishop et al. 2016). The use of the OPFI framework provides a comprehensive framework integrating information from both standardised tests (i.e., assessments of language, cognition, or motor skills) and functional impacts (i.e., difficulties in daily and meaningful activities, school performance and social interactions). This highlights the importance of considering diverse contexts and subjective experiences, as proposed by Kwok et al. (2023), and involving children, parents and professionals in the evaluation process, as suggested by Bishop et al. (2016). While tools like FOCUS (Thomas-Stonell et al. 2010) are valuable for assessing communicative participation, they are not designed to diagnostically assess functional impacts (Waine et al. 2023).

This limitation underscores the need to develop multidimensional tools—grounded in the OPFI model—that extend beyond standardised test scores to capture the complex and context-dependent nature of functional consequences. By integrating functional documentation into assessments, clinicians can adopt a more child-centred approach, better respond to individual needs and ultimately enhance children's quality of life while supporting positive long-term outcomes (McGregor et al. 2020; Morgan et al. 2017; Westby and Washington 2017).

4.7 Service Delivery

Access to specialised services for children with neurodevelopmental disorders remains inequitable, often determined by criteria heavily reliant on standardised testing (Calder et al. 2023; Westby and Washington 2017). While such tests can be helpful in specific contexts, their reliance on rigid criteria can perpetuate disparities in service provision. Underserved children may miss critical interventions, while others may receive unnecessary services. Notably, boys are more frequently identified and offered services, which can disproportionately disadvantage girls (McGregor et al. 2020, 2023). This imbalance exacerbates the functional consequences of disorders: underserved children are left without the support they need, while over-served children may face irrelevant or misaligned interventions. Complementing standardised tests with systematic documentation of functional consequences, which can be facilitated by the use of the OPFI model, might contribute to mitigating these inequities.

4.8 Speech-Therapy Intervention and Promoting Child's Inclusion

The functional consequences of DLD and SLD result from a dynamic interplay between intra-individual factors (e.g., cognitive abilities, emotional regulation and social skills) and inter-individual factors (e.g., family environment, school context and social interactions). These elements collectively influence developmental trajectories, often non-linear in nature, as illustrated in ADHD research by Sibley et al. (2022). Environmental variables alone can account for up to 20% of the variance in a child's functioning (Goldstein and Naglieri 2016, cited in Breault 2023), underscoring the need for tailored interventions rooted in each child's strengths, vulnerabilities and interests (Maillart et al. 2024).

A comprehensive functional assessment, aligned with the proposed OPFI model, should encompass both protective factors which foster resilience and promote participation (e.g., strong family support or inclusive classroom practices), modulating factors which may attenuate difficulties in specific activities or environments (e.g., access to visual supports or emotional regulation strategies) and aggravating factors which can intensify the perceived and observed impacts on the child's daily functioning (e.g., anxiety or exclusionary school settings). Interestingly, some comorbidities may provide compensatory benefits. ADHD co-occurring with DCD can sometimes enhance visuospatial skills, as observed by Biotteau et al. (2017). This suggests that comorbid conditions do not always worsen deficits and may, in some cases, offer functional advantages, as noted by Newcorn et al. (2001). Such observations invite clinicians to reconsider rigid deficit-based views and instead adopt a more nuanced understanding of functional diversity. By broadening our clinical lens to include both observed and perceived functional impacts across everyday contexts, we lay the groundwork for more equitable, context-sensitive and strength-based interventions.

While still in development, the OPFI model may already serve as a useful heuristic support to clinical reasoning and shared decision-making (see Appendix 3 for an illustrative case scenario). The next step is to examine the model's validity in supporting both the functional assessment of DLD and SLD as well as the co-construction of meaningful and individualised goals in clinical practice. Validation of its dimensions and indicators by an interdisciplinary expert committee will be essential to ensure their relevance, clarity and applicability across diverse settings.

5 Conclusion

This scoping review contributes to a deeper understanding of the functional impacts associated with DLD and SLD. By distinguishing between observed and perceived impacts, and by acknowledging their dynamic and context-dependent nature, this analysis offers a more nuanced and comprehensive perspective. The newly proposed definitions address prior calls in the literature for the establishment of a shared terminology. Furthermore, the identification of key dimensions and indicators necessary to document the effects of these disorders on daily and meaningful activities, as well social relationships, contributes to the standardisation of evaluation practices and has the potential to enhance the effectiveness of clinical assessments and interventions.

The OPFI model stands as a central contribution, integrating both objective observations and subjective experiences to assess the impact of these disorders on daily life and relationships. This structured framework fosters consistent assessments, intervention planning, and collaborative efforts amongst speech-language pathologists, families and other stakeholders.

The findings of this study may inform educational and medical policy strategies, particularly regarding access to specialised services, and promote inclusive and equitable practices. Future work in the development of assessment tools should prioritise the separate evaluation of individual abilities, contextual performances and the subjective aspects of the child's experience.

Looking ahead, potential avenues for future research will be to explore the applicability of the conceptual framework (definitions and model) to other populations with neurodevelopmental disorders or from a longitudinal study to track developmental trajectories, identify potential predictors and establish causal links. Focusing on such populations will improve the understanding of how perceptions and experiences change over time and which factors influence their development.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank Chantale Breault and Chantal Desmarais, met during my research trip in Quebec, for their insights that helped shape this conceptual framework. I am also grateful to Albane Plateau for her graphic contribution to the model. Finally, I thank the two speech-therapist students, Anna Arrive and Nathan Perrot, for their collaboration in the interrater reliability process. This study did not receive any specific funding. A research trip that allowed exchanges from researchers from Quebec received funding from the GRIPI, the Université of Clermont Auvergne and the Office Franco-Québecois pour la Jeunesse.

Ethics Statement

Given the nature of the study, formal certification was not required.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Permission to Reproduce Material From Other Sources

All third-party materials used in this manuscript have been properly cited and were reproduced with permission, where required.

Appendix 1

List of keywords in French and English used for the systematic search

| Concept 1: Population | Concept 2: Repercussion | |

| Title / abstract | All fields | |

|

trouble du langage OR language disorder* OR learning disabilit* OR learning disorder OR trouble développemental du langage OR trouble spécifique du langage écrit OR trouble des apprentissages mathématiques OR dysphasie OR dyslex OR dyscalcul* OR DLD OR SLI OR SLD OR TSLO OR TLO OR TSLE OR TDL OR TAM |

AND |

functional communication OR function* impair* OR functional impact OR functional barrier* OR functional strenght* OR functional limitation* OR functional outcome* OR functional weakeness* OR functional disabilit* OR functional difficult* OR functional problem* OR functional deficit OR répercussions fonctionnelles OR conséquences fonctionnelles OR impacts fonctionnels OR retentissement fonctionnel |

- Abbreviations: DLD, Developpemental Language Disorder; SLD, Specific Learning Disorders; SLI, Specific Language Impairment; TAM, Trouble des Apprentissages Mathématiques; TDM, Trouble Développemental du Langage; TLO, Trouble du langage oral; TSLE, Trouble Spécifique du Langage écrit; TSLO, Trouble Spécifique du Langage oral.

Appendix 2

Included data sources

| First author | Year | Country | Type of source | Origin of source | Study design / Type of document | Participants groups (total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backenson | 2015 | Canada | Article | Journal of Learning Disabilities | Retrospective | 123 (95 boys and 48 girls) |

| Bagnato | 2017 | Italy | Article | International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence | Cross-sectional | 32 |

| Bakopoulou | 2016 | United-Kingdom | Article | Research in Developmental Disabilities | Meta-analysis | 42 (37 boys and 5 girls) |

| Baldi | 2018 | Italy | Article | Dyslexia | Cross-sectional | 96 (64 boys and 32 girls) |

| Biotteau | 2016 | France | Article | Child Neuropsychology | Cross-sectional | 67 (44 boys and 23 girls) |

| Bishopa | 2016 | United-Kingdom | Article | Plos one | Delphi | X |

| Bishop | 2017 | United-Kingdom | Article | Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry | Delphi | X |

| Blanchet | 2022 | Canada | Article | Children | Scoping review | X |

| Bradbury | 2021 | United-Kingdom | Book chapter | Paediatrics and Child Health | X | X |

| Bruce | 2019 | Sweden | Article | Child Language Teaching and Therapy | Longitudinal | 4 (2 boys and 2 girls) |

| Calder | 2024 | Australia | Article | International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders | Longitudinal | 1626 |

| Caldera | 2023 | Australia | Article | International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology | Longitudinal | 1626 |

| Chana | 2019 | China | Article | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Cross-sectional | 4114 (1905 boys and 2209 girls) |

| Chieffo | 2023 | Italy | Article | Children | Prospective | 191 (108 boys and 83 girls) |

| Crish | 2022 | USA | Thesis | Exceptional Children | Meta-analysis | 10942 |

| Cuperus | 2014 | United-Kingdom | Article | International journal of developmental disabilities | Cross-sectional | 237 (157 boys and80 girls) |

| Curtisa | 2018 | USA | Article | Pediatrics | Meta-analysis | X |

| Duff | 2023 | USA | Article | Journal of Learning Disabilities | Longitudinal | 437 (205 boys and 232 girls) |

| Eadie | 2018 | Australia | Article | International Journal of Language & Communication Disorder | Longitudinal | 872 |

| Finlay | 2013 | United-Kingdom | Article | Research in developmental disabilities | Cross-sectional | 109 |

| Fisher | 2019 | USA | Article | American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology | Cross-sectional | 92 (54 boys and 38 girls) |

| Flapper | 2013 | Netherlands | Article | Research in Developmental Disabilities | Cross-sectional | 65 (43 boys and 22 girls) |

| Gough Kenyon | 2022 | United-Kingdom | Article | International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders | Longitudinal | 107 (49 boys and 58 girls) |

| Haythorne | 2022 | United-Kingdom | Article | British Journal of Learning Disabilities | Scoping review | X |

| Helland | 2017 | Norway | Article | Research in Developmental Disabilities | Cross-sectional | 43 (37 boys and 6 girls) |

| Hsu | 2014 | Taiwan | Article | Developmental Science | Cross-sectional | 96 |

| Huanga | 2020 | China | Article | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Cross-sectional | 240 (157 boys and 83 girls) |

| Ibáñez-Rodríguez | 2021 | Spain | Article | Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología | Cross-sectional | 42 (30 boys and 12 girls) |

| Jacob | 2017 | France | Article | Neuropsychiatrie de l'enfance et de l'adolescence | Literature review | X |

| Kuusisto | 2017 | Finland | Article | International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders | Cross-sectional | 44 (36 boys and 8 girls) |

| Lin | 2022 | Taiwan | Article | Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology | Longitudinal | 3854 (2343 boys and 1511 girls) |

| Lyons | 2018 | Ireland | Article | Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research | Narrative inquiry | 11 (4 boys and 7 girls) |

| Mackie | 2014 | United-Kingdom | Article | Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties | Cross-sectional | 77 (77 boys) |

| McGregor | 2020 | USA | Article | Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools | Review literature | X |

| McGregor | 2020 | USA | Article | Perspectives | Tutorial | X |

| McGregor | 2023 | USA | Article | Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools | Longitudinal | 79 |

| Miller | 2013 | Canada | Article | Disability & Rehabilitation | Cross-sectional | 174810 (111 440 boys and 63 770 girls) |

| Mok | 2014 | United-Kingdom | Article | Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry | Longitudinal | 171 (128 boys and 43 girls) |

| Nachshon | 2019 | USA | Article | Acta Paediatrica | Cross-sectional | 98 |

| Nicola | 2015 | Australia | Article | Health and quality outcomes | Cross-sectional | 43 (30 boys and 23 girls) |

| Nielsen | 2018 | USA | Article | Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment | Cross-sectional | 155 (94 boys and 61 girls) |

| Norbury | 2017 | United-Kingdom | Article | Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry | Longitudinal | 499 |

| Ottosson | 2022 | Sweden | Article | Acta Paediatrica | Longitudinal | 85 (55 boys and 30 girls) |

| Pauls | 2016 | Canada | Article | Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research | Meta-analysis | X |

| Reilly | 2014 | Australia | Article | International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders | Response | X |

| Robinson | 2019 | Canada | Article | Exceptionality Education International | Literature review | X |

| Singer | 2023 | Netherlands | Article | International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders | Literature review | X |

| St Clair | 2019 | United-Kingdom | Article | Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research | Longitudinal | 14 494 (7 334 boys and 7160 girls) |

| Stipanicic | 2016 | Canada | Article | Journal of Developmental Disabilities | Synthesis | X |

| Suhaili | 2019 | Malaysia | Article | The Medical journal of Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 148 |

| Tseng | 2023 | Taiwan | Article | Research in Developmental Disabilities | Cross-sectional | 32 (14 boys and 12 girls) |

| Waine | 2023 | United-Kingdom | Article | International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders | Survey | X |

| Westbya | 2017 | USA | Article | Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools | Tutorial | X |

- aStudies identified from reference list of included studies.

Appendix 3: Scenario case: illustration of OPFI model application

Liam (8 years old)

-

Assessing observed and perceived functional impacts