A rare case of pulmonary adenoid cystic carcinoma with liver metastases treated effectively with stereotactic body radiation therapy

Abstract

Pulmonary adenoid cystic carcinoma (PACC) is an extremely rare neoplasm. Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) usually occurs in the salivary glands of the head and neck. Given its rare occurrence, there are no established guidelines for the treatment of progressive and/or relapsed disease. We herein report a case of a 57-year-old female who was incidentally found to have biopsy confirmed PACC following trauma diagnostic workup. She underwent pneumonectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy with an initial good response. On follow-up a year later, she was noted to have two metastatic liver lesions treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) and lenvatinib. This case report adds to the growing area of research on PACC, especially among patients requiring SBRT for oligometastatic disease.

1 INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary adenoid cystic carcinoma (PACC) is an unusual form of lung cancer. It accounts for approximately 0.04%–0.2% of all primary lung cancers.1 This tumor is reported to mostly arise from the major and minor salivary glands, and lacrimal glands2 and less commonly at other sites including breast, skin, uterine cervix, prostate, and upper respiratory tract. Unlike other pulmonary cancers, PACC is not associated with smoking. It is considered a low-grade pulmonary cancer characterized by a protracted clinical course and a high risk of recurrence and metastasis.

We report a case of a 57-year-old female who had pneumonectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy for adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) of the lung. On follow-up about a year later, she was found to have two liver lesions which were biopsied and confirmed to be metastatic ACC. She was successfully treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) and lenvatinib.

2 CASE PRESENTATION

A 57-year-old female with no significant past medical history and a nonsmoker initially came to the emergency department after 3 days of wrist and back pain following a fall on her outstretched hands while roller skating. Cervical spine and chest X-rays revealed that no fractures but prominent parenchymal abnormalities in the left hemithorax were noted. Subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a mild compression fracture of thoracic spine vertebra level 5 as well as a left hilar mass invading the left mainstem bronchus with complete atelectasis of the left upper lobe and loculated hydropneumothorax in the left apex.

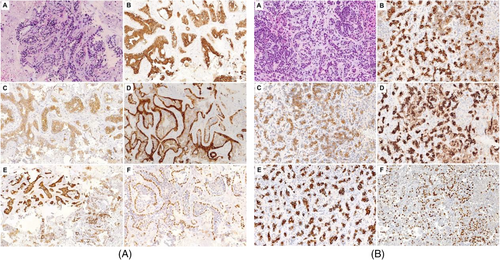

She was evaluated by interventional pulmonology and underwent endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy. Pathology revealed adenoid cystic carcinoma (Figure 1A). Given her good performance status with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scoring of 1, she was deemed to be a surgical candidate. She underwent left pneumonectomy which revealed a 5.8 cm ACC involving the hilum of the lung with main bronchus occlusion. The carcinoma invaded the hilar adipose tissue and involved six of 16 hilar and peri bronchial lymph nodes. The carcinoma was present at the bronchial margin and hilar staple line.

Adjuvant radiation therapy was recommended due to the positive margins and lymph nodes. She completed 66 Gy in 33 fractions utilizing conventionally fractionated conformal radiotherapy given her positive margins. She remained on active surveillance. One year after the diagnosis, she was noted to have an ill-defined hypodense lesion in the central aspect of the right hepatic lobe which had grown from 1.5 to 2.4 cm within 6 months. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen showed two liver metastases in the right hepatic lobe dome measuring 1.4 × 1.6 cm with a second lesion measuring 1.8 × 2.1 cm more inferiorly. Interventional radiology-guided liver biopsy of the right liver metastasis revealed metastatic ACC (Figure 1B). Immunohistochemistry revealed the tumor cells to be positive for AE1/3, CK7, p63, c-KIT, and CK 19, and negative for calponin, CK20, and CDX-2 supporting the diagnosis.

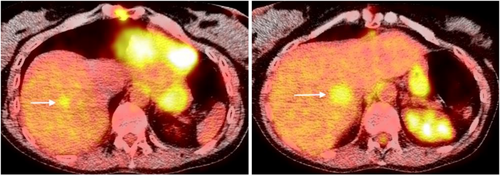

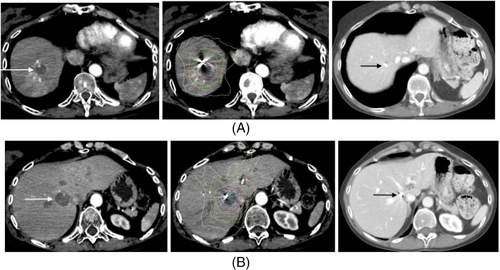

The patient transferred her care to our facility after moving to our area. She was treated by medical oncologists and radiation oncologists. Positron emission tomography/CT scan revealed two masses in the right liver measuring 1.5 cm with max standard uptake value (SUV) of 2.8, and 2.0 cm with max SUV of 3.6 (Figure 2). She was presented at tumor board and combined stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) and levatinib were recommended. Two fiducials were placed by interventional radiology for tracking both liver metastases. She received SBRT utilizing the CyberKnife system sequentially for both liver metastases (Figures 3A,B). 45 Gy was delivered to the hepatic dome metastasis with a 5 mm margin prescribed to the 69% isodose utilizing 137 beams and iris (15, 25 mm collimators). Two weeks later she received 50 Gy to the medial right hepatic lobe metastasis with 5 mm margin prescribed to the 65% isodose utilizing 134 beams and iris (15, 25, and 35 mm collimators). Each metastasis was tracked with the synchrony/fiducial technique for real-time tracking of the tumor during SBRT with respiration. The medial right hepatic lobe metastasis was treated in five fractions to minimize toxicity to the bile duct while the hepatic dome metastasis was treated with three fractions. Organs at risk contoured included the liver, bile duct, small and large bowel, stomach, lung and heart and were within radiation tolerance.

She was started on systemic targeted therapy with lenvatinib 4 mg once daily prior to initiation of radiation therapy. Lenvatinib was discontinued due to severe nausea and vomiting during the first course of radiation. She subsequently tolerated SBRT well but was maintained on pretreatment zofran prior to daily SBRT. She was restarted on a half dose of lenvatinib which she has subsequently tolerated well and has been maintained at that dose level. Molecular testing was done, but it was not helpful in defining targetable treatment options.

The patient is being monitored actively with CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis with intravenous contrast every 6 months and she remains with no evidence of recurrence and complete radiographic response in the liver 18 months following SBRT.

3 DISCUSSION

PACC is a rare salivary gland-type neoplasm that infrequently presents as a primary tumor of the airway or the lung parenchyma.2 Of the 1200 cases of ACC diagnosed annually in the US, 17% occur in the pulmonary system.3 PACC constitutes about 0.04%–0.2% of all primary pulmonary tumors.4 Because PACC grows slowly and has a long clinical course, it is classified as a low-grade malignancy. In a study by Takanori K et al., the median age at presentation was 46 years.5 Reports on gender predilection in the literature have been inconsistent, with some authors stating equal gender predisposition and others with a male predominance.6-8 Smoking appeared not to be a significant risk factor in the etiology of PACC, as only 32.4% of patients reported a history of smoking. The most common pulmonary site affected is the tracheobronchial tree, with limited reports of PACC manifesting in the pulmonary parenchyma. Moreover, among patients with ACC of the salivary gland, the primary site of metastasis is the lung. Therefore, in patients with PACC occurring in the lung periphery, it is paramount to rule out lung metastasis from a primary salivary gland tumor.4

The exact etiology of PACC remains unknown. Fortunately, current research has shown the presence of consistent genetic mutations in the variety of ACC tumors irrespective of the tumor location.9 The translocation at t(6;9) (q22-23;p23-24) in ACC results in fusions encoding chimeric transcripts predominantly consisting of MYB exon 14 linked to last coding exons of Nuclear Factor 1/B (NFIB).10, 11 Furthermore, even in the absence of an MYB-NFIB translocation, MYB overexpression is seen, implying a possible nontranslocation-based mechanism of MYB overexpression.12 Fortunately, these mutations and downstream proteins can serve as possible diagnostic targets in cases of diagnostic ambiguity and be an avenue for therapeutic targets.

Although the microscopic appearance of ACC is heterogeneous, the cytology of the cancer cells remains uniform.6 ACC tumors are characterized histologically by abnormal nests or cords of epithelial cells that surround and infiltrate ducts or glandular structures. The histological growth pattern described includes tubular, cribriform, and solid patterns. There are conflicting reports regarding the correlation of histological growth patterns and the clinical behavior of the tumor. Some authors report a less aggressive clinical course with the cribriform pattern compared with the more aggressive course seen in solid histological phenotype.1, 4, 6 Our patient had tubular growth pattern, which is reported to be an aggressive pattern. Immunohistochemistry and electron micrography revealed the presence of myoepithelial and secretory glandular elements, which can not only aid in diagnosing ACC but exclude other forms of primary lung cancers with solid and tubular patterns.4 PACC tumors are grossly identified as endobronchial,7 with most arising from the submucous bronchial gland.8 PACC, despite its relatively slow and indolent development, can be more aggressive.4 Prognosis depends on primary therapy, surgical margin status, tumor histological subtype, and tumor staging.4, 8 Complete surgical resection with negative margins is preferred as the first-line therapy for localized PACC. In a study by Wang et al., the 5-, 10-, and 20-year survival rates for surgical therapy were 85%, 63%, and 47%, respectively, while the 5- and 10-year survival rates of the nonoperative group were 63.70% and 46.40%, respectively.13

Patients with oligometastatic disease defined as a limited number of metastases (1–5 metastases) may achieve long-term disease control, or even cure if all sites of disease can be ablated. Among local treatments, SBRT is an advanced form of ablative radiotherapy which delivers precise doses of radiation to the target with narrow margins, therefore providing high local control and low toxicity. Retrospective and randomized trials have shown the benefit for SBRT in many types of primary cancer, but few including ACC have been published. Tyan et al. reported that oligometastatic ACC is common and if treated early with SBRT or surgery, patients had improved outcomes which were not seen if early systemic therapy was utilized.14 A current randomized trial (SOLAR NCT04883671) for ACC with three or fewer oligometastases will demonstrate whether there is any benefit of SBRT over standard palliative radiation or systemic therapy (Table 1).

| Study, year | Randomized | Number of patients | Number of sites | RT regimen | Outcomes | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gomez et al. (2016)21 Non-small-cell lung cancer |

Yes, phase II | 49 | Less than 3 | SBRT, surgery, hypofractionated RT, conventional RT | Median OS 41.2 months SBRT vs. 17 months control | No grade 4 or more toxicity |

|

Iyengar et al. (2018)22 Non-small-cell lung cancer |

Yes, phase II | 29 | Less than 5 | SBRT | Median OS not reached SBRT vs 17 months control | No grade 4 or more toxicity |

|

Palma et al. (2012)23 Variety of cancer types |

Yes, phase II | 99 | Less than 5 | SBRT | Median OS 50 months SBRT vs 28 months control | No grade 4 or more toxicity |

- Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; RT, radiotherapy; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

Franzese et al. and his colleagues performed a retrospective multicenter study for the treatment of oligometastatic adenoid cystic salivary gland carcinoma with palliative RT or SBRT.15 The median dose of SBRT used by Franzese et al. was only 29 Gy in three fractions. (Table 2).

| Groups | Number of patients | Doses | Sites | Outcomes (local control at 12 months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palliative RT group | 34 patients | 3 Gy × 10 consecutive fractions, 4 Gy × 5 consecutive fractions, or 8 Gy in a single fraction | Bone (n = 16), lung (n = 9), brain (n = 3), other (n = 6) | 37.8% |

| SBRT group | 30 patients | 20-28 Gy in a single fraction to 21–54 Gy delivered in three to five fractions | Lung (n = 16), brain (n = 10), bone (n = 4) | 57.5% |

- Abbreviations: RT, radiotherapy; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

In contrast, Mahadevan et al. reported the Radiosurgical Society Registry of liver metastases treated with SBRT with a median SBRT dose of 45 Gy delivered in a median three fractions. With doses above BED10 ≥ 100 Gy, local control rates exceeded 80%, especially with smaller tumor size.16 As shown in this case report, typical ablative doses like those used by Mahadevan were used for our patient with excellent local control and survival.

Very little has been reported in the literature regarding SBRT for PACC with oligometastases to the liver. In our patient, owing to positive margins and lymph nodes, adjuvant radiation with standard conventionally fractionated radiation with typical postoperative doses for positive margins was utilized to reduce significant risk of local failure in the chest. She received standard SBRT doses to the liver (45–50 Gy) which should be expected to control >85% of liver metastases. She is currently no evidence of diseases with durable complete radiologic response in the liver 1.5 years following SBRT. She had a durable complete clinical response in the chest following surgery and postoperative radiation 2.5 years from completion of radiation.

The role of chemotherapy in PACC remains unclear, given the limited objective response in single-agent chemotherapy and increased toxicity with combination chemotherapy.17 At this time, chemotherapy is generally reserved for palliation in localized recurrent or metastatic disease.18 Recent studies using multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the relapsed and metastatic setting report modest objective responses with overall response rates of only 30%.19-21 Our patient remained stable on lenvatinib, which is a kinase inhibitor. However, a major challenge in evaluating targeted therapies in PACC is uncertainty if the observed response is due to the protracted nature of the disease or due to the antitumor effect of the drugs.19

4 CONCLUSION

PACC is a slow-growing and indolent tumor, but long-term recurrence and metastasis are common. Treatment of relapsed and refractory ACC remains a significant therapeutic challenge. ACC should not be considered radiation resistant and durable responses can be obtained with tumoricidal doses. As for more common histologies, SBRT can be used with durable clinical response for oligometastases and should be considered for ACC since systemic therapy is not highly active. Close follow-up of patients should be considered to detect and treat early oligometastases for PACC with SBRT or resection. Further research on target therapies and immunotherapy are mandatory for PACC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.