The CT and pathological features of intestinal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

Ming Zhou and Zhongchao Wang contributed equally to this study.

Abstract

To explore computed tomography (CT) findings and pathological features of intestinal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMT). A retrospective review was conducted on the CT features of five patients with pathologically confirmed IMT, which were then compared with the corresponding pathological findings. The study included four female and one male patients. The tumors were located in the rectum (n = 1), small intestine (n = 2), or cecum (n = 2). One patient exhibited a cystic solid mass with exophytic growth and the solid components showed moderate enhancement. Additionally, flaky low-density, marginal line-like calcified shadows were observed around the lesions. Two cases presented as solid masses within the lumen of the intestinal tract, showing obvious non-uniform enhancement along with visible enhancement shadows of small blood vessels. One patient had a metastasis. In two other cases, solid masses grew outside the lumen of the intestinal tract, demonstrating progressive and delayed enhancement on enhanced scans, as well as local nodular enhancement and ring enhancement. These two cases also exhibited focal sarcomatoid lesions, along with their respective IMTs. Histologically, these tumors mainly consist of proliferating spindle myofibroblast cells accompanied by variable infiltration by interstitial inflammatory cells, such as fibroblasts. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed positive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) in ~80% of the cells tested, while vimentin staining was positive in ~60% of the cells. Intestinal IMT is an extremely rare tumor with imaging features that can reflect the underlying pathological characteristics to some extent, thus aiding diagnosis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare low-grade mesenchymal malignancy, characterized by the presence of myofibroblast spindle cells, interstitial lymphocytes, plasma cell infiltration, and other inflammatory cells. Recurrence and metastasis are uncommon.1, 2 The abdominopelvic region, lung, mediastinum, and retroperitoneum, are frequent sites, and uncommon sites include the central nervous system, upper respiratory track, and solid organs.2 However, reports of intestinal IMT imaging are scarce. The clinical presentation is determined by the site of origin and the effects of the mass. A small proportion of patients have a syndrome of fever, weight loss, growth failure, malaise, anemia, thrombocytosis, polyclonal hyperglobulinemia, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.1 Because clinical symptoms and laboratory test results lack specificity for the diagnosis of intestinal IMT, preoperative imaging based examination is very important for identifying such IMTs and choosing the appropriate way to manage them. This study aims to collect clinical, CT imaging, and pathological data from patients with primary intestinal IMT, along with a review of the relevant literature to enhance the understanding of IMT and improve the level of imaging diagnosis.

2 DATA AND METHODS

2.1 Research object

The clinical, imaging, and pathological data of five patients with intestinal IMT, confirmed by postoperative pathological examination, were collected in North Jiangsu Province from October 2013 to May 2023. All cases originated in the intestine and included one male and four females aged between 43 and 67 years (mean 56.2 years, median 56 years). The predominant clinical symptoms of intestinal IMT are compression and obstruction. In this study, one patient presented with difficulties in defecation, another presented with vomiting, and three experienced abdominal pain and distension.

2.2 Scanning methods

CT examinations were performed on all five patients, two underwent both abdominal plain and enhanced scans, while the remaining three only underwent abdominal enhanced scans using a GE Light Speed VCT 64 spiral CT machine. Before the scan, the patient typically underwent an 8-h fasting period and consumed three doses of a 2.0% meglumine solution, each consisting of 1500 mL, at intervals of 1.5 h before the scan to adequately fill the intestine. During the contrast-enhanced scan, iodihexol (300 mg I/mL), a contrast agent, was injected intravenously through the cubital vein at a dose range of 80–100 mL and administered at a rate between 2.5 and 3.0 mL/s. The arterial phase was scanned ~25–30 s after contrast agent injection, while the venous phase was scanned 60–70 s later. The scanning process used layers with thicknesses and spacings of 5 mm each.

2.3 Image analysis

The CT imaging data were analyzed by two physicians with over 5 years of experience in diagnostic imaging, and a consensus was reached through consultation and discussion. Lesion evaluation primarily included assessing the lesion's location, size, shape, boundary, density, and enhancement characteristics, as well as whether the lesion had invaded neighboring tissues or metastasized distantly. The lesion size was measured using the transverse diameter × anterior and posterior diameters. After enhanced scanning, an increase in the CT value to <20 HU was considered as mild enhancement, 20–40 HU indicated moderate intensification, and >40 HU represented significant enhancement. For lesions that only underwent enhanced scanning, the degree of enhancement was based on the muscle tissue from the same layer; higher CT values indicated significant enhancement, whereas lower values suggested mild enhancement.

3 RESULTS

3.1 General information

Among the five patients, one lesion was located in the rectum, two in the small intestine, and two in the cecum. The diameters of the lesions ranged from 33 to 78 mm (mean diameter 63 mm, median diameter 64 mm).

3.2 CT findings

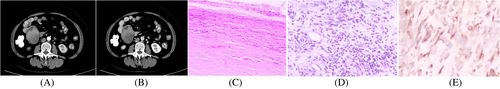

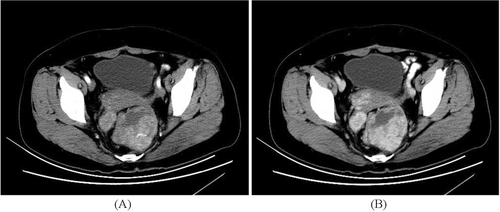

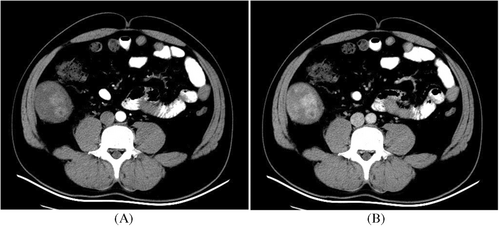

Of the five cases with intestinal lesions, three showed outward growth of intestinal soft tissue masses, whereas two exhibited intestinal lumen masses with thickened walls. Three cases displayed equal-density shadows, whereas two presented mixed shadows of equal and low density, along with cystic changes and necrosis. One patient showed a linear calcification at the edge of the lesion. All five lesions demonstrated sustained enhancement on enhanced scans: one patient showed moderate intensity, while four others exhibited obvious enhancement with uneven distribution and nodular or circular enhancements within the lesions. Two cases also displayed flaky low-density cystic and necrotic shadows (Figures 1-3).

Among these five cases of intestinal IMT lesions, one case was adjacent to the psoas major muscle causing compression on a urinary catheter, resulting in a dilated renal pelvis and hydronephrosis, another case involved intussusception in the small intestine, one case occurred in the rectum leading to difficulty defecation as well as liver, abdominal, and pelvic metastases; and sarcomatoid change occurred in one case involving the cecum.

3.3 Pathological findings

All five patients underwent routine H&E and immunohistochemical examination after IMT. The microscopic tumors consisted of proliferating fusiform myoblasts and fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were formed with interstitial inflammatory cell infiltration; two patients had cell atypia and mitosis, and one patient had interstitial blood vessels. Accretions and expansion. Immunohistochemistry showed SMA positivity in four cases and strong vimentin positivity in three cases. The Ki-67 proliferative index increased in one case, 60% of which were positive; the rest were <10%, and two cases were calponin-positive. Two cases were CD68 positive, one was CD34 positive, and the other markers were negative.

4 DISCUSSION

IMT is a rare mesenchymal tumor primarily composed of myofibroblast spindle cells and inflammatory cells, initially identified by Philips, in the lungs.3 Previously known as inflammatory pseudotumor, myofibrocytoma, and plasma cell granuloma, it was officially classified as a fibroblast/myofibroblast tumor (intermediate, with few metastases) by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2002.2 The exact etiology of IMT remains unclear. Approximately half of IMTs harbor a clonal cytogenetic aberration that activates the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-receptor tyrosine kinase gene on the short arm of chromosome 2 at 2p23, The ALK abnormality generally leads to ALK protein overexpression and is detectable by immunohistochemistry, which typically demonstrates cytoplasmic reactivity in IMT, and is also detectable by conventional cytogenetics, FISH, and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.4, 5 ALK reactivity was associated with local recurrence, but not distant metastasis, which was confined to ALK-negative lesions. Absent ALK expression was associated with a higher age overall, subtle histologic differences, and death from disease or distant metastases (in a younger subset).5 Additionally, IMT may be associated with infections, the Epstein–Barr virus, or autoimmune diseases. Although IMT can occur in any age group, it predominantly affects children and young adults. The average age in this cohort was 56 years, and the youngest patient was 43 years. Although the lung is the most common site of IMT,2 extrapulmonary locations, such as the liver viscera and pelvic bladder mesentery retroperitoneum, have also been observed.6 However, IMT of intestinal origin is relatively uncommon and this study primarily focused on patients with intestinal involvement. The clinical manifestations of IMT lack specificity; however, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and complications, such as intestinal obstruction and intussusception caused by an abdominal mass, are commonly reported in cases involving the intestine. Despite their benign biological behavior, only a few individuals experienced recurrence or metastasis during follow-up examinations; however, in this study, two patients presented with focal sarcomatoid lesions, while one patient exhibited distant metastases detected later on follow-up, revealing a pathological examination characterized by excessive proliferation of spindle cells accompanied by infiltration of lymphocyte plasma cells. Scattered fibrous component mucous matrix was also observed, inside. Histopathologically, IMTs can be categorized into three subtypes7: (1) The mucus/blood vessel exhibits high density, with spindle cells distributed in a large amount of immature new blood vessels and mucous matrix, accompanied by numerous inflammatory cells. (2) The spindle-shaped cells were densely arranged under the microscope, with only scattered inflammatory cells. Fibrous-type IMT show a sparse cell distribution with dense hyalinoid collagen fibers between tumor cells. Two or more IMT subtypes co-exist. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed positive expression of myogenic proteins in IMT, mainly vimentin and SMA.8 Previous studies have shown that vimentin has strong positive expression, whereas SMA is more specific than vimentin.8 Four cases showed SMA-positive expression while only three cases exhibited strong vimentin expression. Intestinal IMTs mostly exhibit round or irregular mass shapes growing inside or outside the lumen, and some intracavitary lesions are accompanied by tube-wall thickening. Owing to the large abdominal space and easy compression of surrounding tissues, these masses tend to be larger in size. The chest and abdominal regions had higher incidence rates of IMT lesions than other sites. In this study, lesion lengths ranged from 33 to 78 mm similar to thoracic and abdominal IMTs reported in literature reviews. The pathological tissue composition of IMT results in various components and subtypes leading to different CT imaging manifestations. In one patient moderate enhancement was observed within the solid component of the tumor along with intrafocal flaky low-density shadows and linear calcification at lesion margins. This may be due to collagen fiber dominance resulting in sparse cell distribution blocking contrast agent entry.10 Pathological examination revealed large, hyaline, and necrotic cystic lesions. In two cases, the soft tissue mass in the intestinal lumen exhibited obvious uneven enhancement, with visible enhancement shadows of small blood vessels. This may be attributed to the granulation tissue and interstitial vascular hyperplasia observed under the microscope, leading to increased permeability of the tumor vascular wall.11 Additionally, solid mass shadows growing outside the intestinal lumen were observed in two cases during the enhanced scans. Progressive and delayed enhancement was evident, and local nodular and circular enhancements could be related to the closely arranged proliferative spindle cells observed microscopically, resulting in slow clearance of the contrast agent and characteristic delayed enhancement. It can be concluded that although imaging findings lack specificity for IMT diagnosis, they do reflect certain features of the lesion pathology to some extent. IMT is a low-grade malignant tumor characterized by rare recurrence and metastasis. However, among the five patients included in this study, one had liver and pelvic metastases, while two presented with focal sarcomatoid lesions on microscopic examination. Relevant literature has demonstrated that abdominal IMT exhibit characteristics of inflammation and invasiveness, resulting in indistinct lesion edges, adjacent peritoneal reactivity thickening, and invasion of the surrounding tissues.12 Studies have also suggested that unclear boundaries of IMT lesions may be associated with their propensity for invasive behavior.10 In this study, the three lesions displayed unclear edges with flocculent exudations. The local boundary with neighboring tissues was also indistinct, and some patients exhibited compression and displacement of neighboring tissues, as reported in related literature.9 Few imaging reports on intestinal IMT exist, and the imaging findings lack specificity; therefore, it is necessary to differentiate it from small intestinal stromal tumors and adenocarcinomas. Small intestinal stromal tumors are highly vascularized tumors that commonly present with internal necrosis and cystic transformation. They often exhibit extracolonic growth patterns with heterogeneous enhancements on contrast-enhanced imaging. Small intestinal adenocarcinomas can grow into the lumen and present as large lesions with indistinct boundaries, frequent cystic changes, and necrosis. The solid portions show moderate enhancement.

In summary, patients with intestinal IMT typically present clinical symptoms caused by abdominal masses. CT scans reveal long solid or solid cystic masses within or outside the intestinal lumen. However, the edges of the invasive lesions are often poorly defined. Contrast-enhanced scans demonstrate uniform moderate enhancement or nodular/annular enhancement that progresses over time, indicating delayed enhancement that reflects certain pathological features. It should be noted that this study included a relatively small number of cases of intestinal IMT; thus, further research with a larger sample size is required.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Zhou Ming and Sun Jun contributed to the design and implementation of this study. Zhou Ming and Wang Zhongchao analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. Zhou Ming and Wang Zhongchao were co-first authors.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This was a retrospective study with no funding support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data supporting this publication are available from the Department of Medical Imaging of Northern Jiangsu People's Hospital.