On the open-source landscape of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine

Click here for author-reader discussions

Abstract

Click here for author-reader discussions

The tides of the open-source movement reached the coast of our journal just prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic with an editorial1 on reproducibility and the future of MRI research. In it the authors argued that, for improved reproducibility, the concept of a “paper” should be extended to encapsulate the entirety of the scholarly work done authors. These extensions should include data and analysis code, which may be as essential to papers as figures and tables. In the spring of 2020, the journal therefore added an optional (but strongly encouraged) Data Availability Statement section to articles, making it easier to access supplementary data and code from an author's linked repository. Also, the journal's outreach initiative, MRM Highlights,1 transitioned from highlighting Editor's Picks, to focusing on articles that demonstrate exemplary reproducible research practices, such as sharing all the data/code needed to reproduce figures, the use of Jupyter/R Markdown notebooks, container technology (eg., Docker, Singularity), interactive figures, etc. In addition to the Highlights interviews that showcased the authors and their publication, each feature was accompanied by an additional written interview where those authors explicitly discussed their reproducible research practices.

In this editorial, we explore the reproducible research practices of the community in the wake of these changes.

It would be interesting to observe what effect these changes had on the reproducible research practices of Magn Reson Med authors. Fortunately, we have an earlier snapshot of the open-source landscape of Magn Reson Med before the changes, captured in a blog post from 2019.2 For this blog post, all the articles published in Magn Reson Med in 2019 were analyzed with an automated script to find which of them contained at least one of a list of keywords related to data/code sharing or reproducible research practices. These were all entered in a spreadsheet, and then manually checked to see if a reproducible research object was really shared, or if it was a false positive. The identified articles were then evaluated based on what was shared (e.g., code, data, etc.), how it was shared (e.g., GitHub, GitLab, personal or institutional website, etc.), and the details of the deliverable (e.g., programming language, additional tools like Jupyter Notebook or Docker, if the content that was shared was sufficient to reproduce some or all figures, etc). Two years later this analysis was repeated3,4 to see how the journal's emphasis on reproducibility had affected the researchers' reproducibility practices. The above procedure was followed almost identically, with minor changes to the keyword list, which is occasionally updated with new keywords that are identified (for example, “Data Availability Statement” after its introduction in 2020). The analysis is shared in a GitHub repo5 and can be reproduced using MyBinder.6 A summary of the results of this analysis for all 3 y is listed in Table 1.

| % of total papers that shared… | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| code OR data | 11 | 14 | 31 |

| code | 9 | 12 | 24 |

| data | 5 | 6 | 18 |

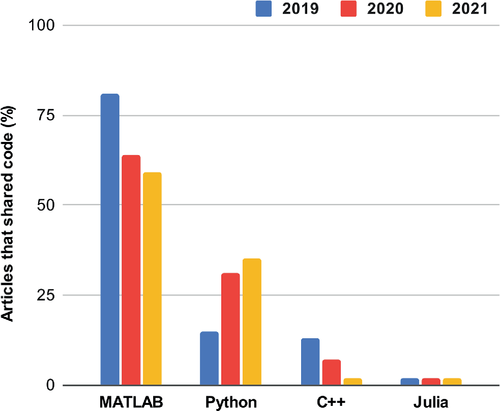

The main findings in 2019 were that approximately 11% of papers (slightly above 1 in 10) shared some reproducible research objects, out of a total of 500 publications that year. The most common hosting website was GitHub (66%), and the most common programming language was MATLAB (81%). Out of those articles that shared some code/data, approximately 12% appeared to share sufficient information to reproduce the article figures. Two years later, the number of articles published in Magn Reson Med that share code and/or data has risen to approximately one in three (31%), out of a total of 514 publications in 2021. A decrease in the use of MATLAB was observed between 2019 (81%) and 2021 (59%) (Figure 1), which was accompanied by an increase in the use of Python (from 15% to 35%). GitHub consistently remained the most used code/data sharing service (66% in 2019, 82% in 2020, and 69% in 2021). Although not tracked explicitly, we saw more and more publications use additional tools such as notebooks, container technology, and interactive figures.

Within the MRI research community, the number of authors that share code and data is increasing. But just sharing something may not be sufficient to maximize the potential impact and usefulness of the work. Taking a little extra time to carefully prepare these resources is crucial, which means documenting things inside and outside of the code, in particular installation details and example use cases. Code without documentation is like a figure without text. Currently, the quality of what is shared in the Data Availability Statement section varies. The most exemplary reproducible research objects included things like: full data and scripts to reproduce and generate article figures, well documented code, installation and/or usage details, links to version-tracked datasets, and software packages.

However, many submissions, although sharing something, leave room for improvement when it comes to value added. For example, code repositories submitted with a single version commit only provide one “snapshot” of the projects. Readers benefit more if version tracking of the code is done from the beginning, providing a richer history of how the project evolved, as well as commit messages providing the rationale for changes. Demo scripts or notebooks, meant as simple examples of an implementation are often useful for readers to gain additional insights into an article, but can be further improved if they incorporate actual figures from the papers in the aim to reproduce them. In some cases, the Data Availability Statement was not used as intended for reproducible research practices, but rather contained information such as: statements that data or code were available upon reasonable request; links to empty repositories; or broken links. These remarks are not intended to discourage sharing if authors cannot do it perfectly. However, they should serve as a reminder that, although sharing something is always better than sharing nothing, properly preparing what you share will make your work more reproducible and give it greater impact. And, as other fields have reported, data sharing alone is not always sufficient for other groups to reproduce analyses.2

Currently, this journal, like many others, does not require reviewers to evaluate the code and/or data that authors provide (indeed sometimes data and code are provided only after acceptance of the manuscript), so it is mostly assumed that mistakes or improvements will be raised by readers post-publication. This type of ongoing post-publication discourse may occur on the code/data repository hosting websites (eg., “issues” in GitHub), but could also be raised in community forums, such as the MRM Discourse Forum7 that we launched as a pilot project in 2021 to host more reader-author dialogues about the articles published in Magn Reson Med.

Just as the advent of computers made it easier to generate and share figures in articles, the advent of widely used tools such as GitHub/GitLab, code notebooks, and containers is making it easier to share reproducible research. Increasingly, many MRI researchers are adopting some of these practices, and those ignoring this new wave of best practices may in any case be forced to adopt them as some institutes/agencies/journals begin to impose open sharing mandates.8 Complementing this journal's efforts, many community-driven initiatives have taken shape, such as MR-Pub,9 conference and workshop challenges,3-5 and hackathons.10 Developing reproducible research practices not only benefits our community, but also serves as a benefit to the researchers themselves, by keeping more intergenerational knowledge in the lab; after students graduate, incoming students in the lab are better equipped for reproducing previous work, and building on that work. An ongoing challenge is that most researchers are still not properly recognized by funding agencies for having developed reproducible research practices in their lab and for sharing it with the community. Nonetheless, there is growing recognition across journals6, 7 that reproducible research objects that incorporate code and data are important for their readership and communities. This is slowly also translating to a growing recognition among funding agencies that this activity is important. Hopefully, the Magn Reson Med community can be part of this valuable effort.

ENDNOTES

- * https://blog.ismrm.org/category/highlights/

- † https://qmrlab.org/2019/08/16/mrm-open-source.html

- ‡ 2020 Analysis spreadsheet: https://osf.io/qsa4x/

- § 2021 Analysis spreadsheet: https://osf.io/76ufq/

- ¶ https://github.com/mathieuboudreau/mrm_analysis

- ** https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/mathieuboudreau/mrm_analysis/HEAD?labpath=analysis.ipynb

- †† https://mrm.ismrm.org/

- ‡‡ https://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing/data_sharing_guidance.htm

- §§ https://ismrm.github.io/mrpub/

- ¶¶ https://mrathon.github.io/