The impact of self-service versus interpersonal contact on customer–brand relationship in the time of frontline technology infusion

Abstract

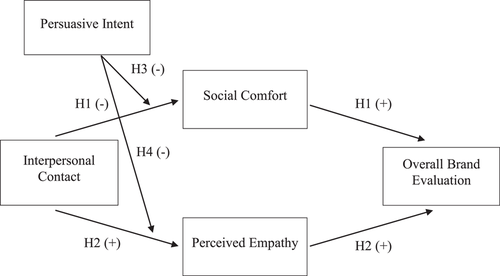

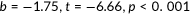

In response to the widespread utilization of contact-free technology in service interactions, this study compares the tradeoffs between self-service technology and interpersonal contact by demonstrating the mediating effects of social comfort and perceived empathy, which eventually impact the overall brand evaluation. Specifically, this study reveals social comfort as an underlying mechanism behind digital customers' preference for self-service technology over interpersonal contact. Also, it recognizes that the relational cost of self-service technology is its lack of empathy with customer needs and that the benefit of human contact is a fulfillment of the consumer need for caring. This study further reveals the moderating role of the service provider's persuasive intent that can increase the benefit and reduce the drawback of interpersonal contact.

1 INTRODUCTION

Although the financial services industry has used self-service technology for some time, the retail industry has mainly depended on frontline service employees to make direct contact and maintain good relationships with customers. However, nowadays, with the help of big data and artificial intelligence technology, a “contact-free” marketing strategy is being widely adopted in the retail industry. For instance, a global cosmetics retailer, Sephora, provides a “smart mirror” service powered by artificial intelligence, which allows its customers to try its makeup products virtually and get information about these products simply by tagging them. Furthermore, a global fast-fashion brand, Zara, opened its first unmanned store in London, where radio frequency identification (RFID)-based simulators allow customers to try on clothes virtually and use a self-checkout service.

One of the important motivations behind this “zero-contact” economy is customers' growing desire for unmanned shopping environments. While firms are driven mainly by the cost efficiency of adopting self-service technology over human labor (Autor & Salomons, 2018), customers seem to use self-service technology not only for its convenience but also for their emotional well-being. Specifically, as Meuter et al. (2000) pointed out, one of the important reasons that customers use self-service technology is that they find it uncomfortable and even burdensome to interact with salespeople during the shopping experience. Indeed, the recent trend of customer avoidance of interpersonal contact with salespeople has been consistently recognized as an issue that needs attention (Torres, 2019). For instance, Sephora provides a shopping basket labeled with an “I would like to shop on my own” sign for customers who feel social discomfort as a result of interactions with salespeople. Furthermore, customers of Uber Black appreciate the “quiet preferred” option that allows for silent rides and a break from the unwanted attention prevalent in this hyperconnected society.

Given the evidence of social discomfort triggered by frontline employees and the crucial role of self-service technology as an alternative to human contact, researchers have started to examine the social and emotional aspects of unmanned service encounters involving self-service technology. For example, Meuter et al. (2000) explored this issue through qualitative research. Giebelhausen et al. (2014) also showed that specific salesperson misbehaviors can trigger social discomfort. Building on this stream of research, the current study examines the role of social discomfort as a sociocultural factor that makes customers prefer self-service technology over interpersonal contact and that eventually impacts customers' affective responses toward brands. In other words, we investigate the relational benefit of self-service technology as an alternative to human contact in service encounters where typical salesperson behaviors bring social discomfort. In addition, we investigate a limitation of self-service technology, which is that it lacks the relational quality of empathy. Finally, by identifying the moderating role of a service provider's persuasive intent, this study provides insights for academics and managers, possibly helping managers better utilize human resources to compensate for the weakness of self-service technology by minimizing the cost (i.e., social discomfort) and maximizing the benefit (i.e., perceived empathy) of human contact.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Salespeople as a source of social discomfort during service encounters

Customers' sense of social comfort1 in the service context is defined as a psychological state “wherein the customer's anxiety concerning a service has been eased, and [wherein] he/she enjoys peace of mind and is calm and worry-free concerning service encounters with service providers” (Spake et al., 2003, p. 321). Social comfort has been consistently recognized as an important relational factor that shapes customer–brand relationship by influencing customers' affective and behavioral responses toward the brand, including commitment, satisfaction, trust (Gaur et al., 2009), word-of-mouth (Lloyd & Luk, 2011), and brand loyalty (Butcher et al., 2001). Unlike physical and physiological aspects of comfort, social comfort is a psychological outcome of social interactions between customers and salesperson. In a traditional service environment that requires human contact, a salesperson, as a direct communication bridge between brands and customers, can influence customers' affective responses through his/her attitude, behavior, and even appearance. For instance, the physical attractiveness of a salesperson activates self-presentation concerns among customers and eventually reduces patronage intentions (Wan & Wyer, 2015). Moreover, a salesperson's competence and relaxing manner increase the social comfort that customers feel during the service experience (Lloyd & Luk, 2011), whereas physical proximity to a salesperson is considered invasive and decreases social comfort in the expressive consumption context (Otterbring et al., 2021).

In sum, previous findings underscore the crucial role of salespeople as a source of social dis/comfort during service encounters. In the traditional service environment, customers had no choice but to endure social discomfort in their relationships with frontline employees. Now, however, with the help of digital innovation, customers are provided with technology that complements or even replaces human labor in various service sectors (Huang & Rust, 2018). Despite this change in service environments, the existing literature mainly examines the antecedents and outcomes of social comfort in traditional settings. Prior research in the self-service technology setting has focused on cognitive antecedents of technology adoption (e.g., Technology Acceptance Model; Davis, 1989; Marangunić & Granić, 2015). Although some studies have recognized the affective (Kulviwat et al., 2007) and social (Nasco et al., 2008) aspects of technology adoption, relatively less attention has been paid to the role of social comfort in the process. To be specific, prior self-service literature has examined social influence as an outcome of the subjective norm (Demoulin & Djelassi, 2016; Nasco et al., 2008; Park et al., 2019; Venkatesh et al., 2012) or social anxiety related to one's fear for the negative evaluation of fellow consumers (Dabholkar & Bagozzi, 2002). Only a few studies have directly addressed the impact of interaction-induced social discomfort in technology-mediated service encounters. Two qualitative studies revealed that customers use self-service technology to avoid social discomfort stemming from interactions with a “moronic salesperson” (Meuter et al., 2000), especially among customers with high dispositional social anxiety (Delacroix & Guillard, 2016). This view is echoed by Giebelhausen et al. (2014), who empirically explored the role of technology as a means to relieve social discomfort arising from a salesperson's negative behaviors that are unacceptable in terms of courtesy, responsiveness, and knowledge or from violations of the social exchange norms that guide customer–employee relationships (e.g., the absence of a warm welcome).

Taken together, past research has explored the impact of social discomfort in populations with specific individual traits, in situations where salesperson misbehaviors occur, or in the presence of fellow consumers who trigger technology-related social anxiety (see Table 1). The present study attempts to extend previous research on social influence by examining social discomfort as a sociocultural factor that reflects the change in consumer behavior in the digital age, and by demonstrating that typical in-role salesperson behaviors can also result in social discomfort among customers.

| Dimension | Main results | Methodology | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology anxiety-related social emotions | Social anxiety activated by the presence of fellow consumers (manipulated by crowding) prevents consumers from using self-service technology out of concern that they may get humiliated by making mistakes in public | Experimental studies | Dabholkar & Bagozzi (2002) | |

| When customers feel social anxiety, user-friendly service design factors (i.e., ease of use, fun, performance) of self-service technology have a greater impact on its usage intentions | ||||

| Individual traits | Subjective norms | Subjective norms in technology adoption models are defined as the extent to which consumers perceive that important others believe individuals should use such technology (Venkatesh et al., 2012) | Correlational studies | Demoulin & Djalassi (2016), Nasco et al. (2008), Park et al. (2019), Venkatesh et al. (2012) |

| Consumers under the social influence of subjective norms show favorable attitudes toward high-technology products/services, and eventually, increase their usage intentions | ||||

| Social anxiety | Consumers with high dispositional social anxietyfeel social discomfort from interacting with salespeople. As a result, they prefer self-service technology that does not require human contact and appreciate anonymity and autonomy it offers | Qualitative research (i.e., In-depth Interview) | Delacroix & Guillard (2016) | |

| Situational factors | Social discomfort | Results from content analysis reveal that one of the reasons that customers use self-service technology is to avoid discomfortelicited from “interacting with a moronic salesperson” | Qualitative research (i.e., Critical Incident Technique) | Meuter et al. (2000) |

| When a salesperson's misbehaviors(i.e., violations of social exchange norms) result in social discomfort, using self-service technology increases service encounter evaluations by relieving the discomfort | Experimental studies | Giebelhausen et al. (2014) | ||

Although prior studies have mainly examined the impact of salesperson misbehaviors (Giebelhausen et al., 2014; Meuter et al., 2000), customers may also feel social discomfort from interacting with a salesperson just doing his/her job (e.g., help and persuade customers to promote sale) when the social nature of service encounters becomes salient. Indeed, service encounters go beyond mere transactions or economic exchanges in the sense that customers perceive a salesperson as a social actor and a target of impression management (Wan & Wyer, 2015). Unlike in economic exchanges where people make decisions based on monetary costs and benefits, in a social exchange of service encounter, customers seek relational rewards of respect and social approval even during a brief encounter with salespeople (i.e., social exchange theory; Blau, 1964; Bradley et al., 2010). Driven by these social needs to make good impressions of themselves, customers feel personal obligations to return the favor of a salesperson by making a purchase. However, in many cases, customers cannot achieve this goal and delay purchase decisions for various reasons: they may have uncertainty about the product, dislike its high price, or want to try out alternative options. In apprehension of such cases when they may suffer from this sense of indebtedness, customers feel social discomfort from interactions with salespeople. Indeed, though limited to those with high dispositional social anxiety, Delacroix and Guillard (2016) revealed that customers feel social discomfort from the situation they have to say no to a salesperson who has faithfully attended to their needs. The impact of social discomfort triggered by in-role behaviors of a salesperson becomes even more important in this digital age where customers can use self-service technology as a means to avoid uncomfortable human contact. With the growing use of self-service technology under digital transformation, customers feel greater social discomfort due to fewer opportunities to make human contact and less need for salespeople as brand informants.

2.2 Relational cost of interpersonal contact: Social discomfort

Under the new social distancing rules imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, contact-free technology has become more important in service interactions. Technology has replaced human contact everywhere from the factory floor to the retail store. However, the coronavirus has merely accelerated a change in shopping habits that had been transforming the service environment ever since the retail self-checkout system was introduced in the early 1990s. Self-service technology, as a technology interface that allows for service delivery without face-to-face interactions between service providers and customers (Meuter et al., 2000), has gained popularity among service providers that pursue cost efficiency (Autor & Salomons, 2018). In this technology-infused service environment, modern consumers routinely interact with automated kiosks and tablets powered by artificial intelligence technology. More interestingly, customers now use self-service technology as a means “to avoid interacting with a moronic salesperson” (Meuter et al., 2000, p.55). Indeed, this trend of customer avoidance of human contact and of preference for technology was captured by researchers and practitioners as an issue reflecting the irreversible change in consumer behavior in the digital age (Hendriksen, 2018; Torres, 2019).

Digital innovations have provided alternative options for consumers who suffer from social discomfort and would rather interact with an automated machine than a salesperson. With less chance to socialize and interact with other people in the offline world and the diminishing role of salespeople as a source of brand information, modern consumers tend to avoid human contact and use self-service technology instead. Specifically, with the help of the Internet and high-tech devices such as smartphones, which allow for ubiquitous communication unbounded by time and space, people can communicate with each other and fulfill their social needs in their own space, without having to endure the social discomfort prevalent in the outside world (Hendriksen, 2018). As a result, digital consumers tend to cling to a few people with whom they feel comfortable and avoid having new relationships with strangers. With this tendency of digital cocooning (Kobayashi & Boase, 2014) or network privatism (S. W. Campbell, 2015), consumers have become more vulnerable to social discomfort arising from interactions with salespeople.

Digitalization has also changed consumers' decision-making process by adding a step of online information search. Traditionally, consumers acquired most of their product information on-site, and frontline employees played an important role as brand informants. Now, consumers are provided with a pool of information through the digital infrastructure of online search engines and social network services. Indeed, it has become a global trend to share personal consumption experiences on social media on a real-time basis, and these shared online reviews and ratings are considered important and credible sources of information (Nielsen, 2015). With the increased accessibility of both firm-provided and customer-created information, customers are in less need of recommendations or explanations from salespeople and are more likely to consider attention from salespeople to be invasive and bothersome.

In summary, with fewer opportunities to make contact with people outside of their comfort zone and less need for salespeople as brand informants, consumers in the digital age are easily intimidated by human interactions and instead turn to self-service technology, which offers a respite from the social discomfort in service interactions. Building on these arguments, we propose that customers would feel greater social discomfort when interacting with a frontline employee than when facing a kiosk in an unmanned store.2 This increased sense of social discomfort would eventually result in less favorable brand evaluation, which predicts long-term customer–brand relationships by measuring customers' affective responses toward the brand (i.e., brand liking, trust, desirability) and future purchase intentions. In other words, the type of service providers (human vs. self-service technology) would influence the quality of the service interaction and eventually impact customers' willingness to continue their relationships with the brands.

H1: Interpersonal contact (vs. self-service technology) decreases the social comfort that customers feel during the service encounter and subsequently overall brand evaluation.

2.3 Relational benefit of interpersonal contact: Perceived empathy

Despite the relational cost of social discomfort, human contact is still an inevitable part of the service experience in that customers want a fellow social being who can empathize with their needs and emotions. A sense of empathy, the ability to understand and respond appropriately to the affective states of others (Hoffman, 2001), is another important relational outcome of social interactions, which individuals learn and develop from the collective knowledge shared in their social relationships (i.e., theories of social construction; Gerth & Mills, 1953; Ruiz-Junco, 2017). Empathy in service encounters is defined as a service provider's ability to sense and react to a customer's thoughts, feelings, and experiences during a service encounter (Castleberry & Shepherd, 1993). Based on this genuine concern for and personal attention to customer welfare, an empathic frontline employee can better understand customer needs and therefore provide customized solutions (Giacobbe et al., 2006). In a social exchange of service encounter, these empathic concerns from salespeople result in gratitude and pleasure, which customers perceive as the relational rewards that motivate them to maintain long-term relationships with the brand/company that is represented by its salesperson (i.e., affect theory of social exchange; Lawler, 2001). Indeed, salesperson empathy has been acknowledged as playing an important role in relationship marketing by increasing customer satisfaction and brand loyalty (Bahadur et al., 2018; Wieseke et al., 2012).

Although it is theoretically possible for artificial intelligence technology to learn social intelligence, most of the commercial self-service machines are yet to reach this stage of development and mechanically repeat standardized messages rather than actually interacting with customers as social beings. Indeed, self-service machines, unlike human beings, have low social presence (Yoganathan et al., 2021) and are less likely to be perceived as a social actor that can empathize with consumers. Even for tech-savvy consumers with high technology readiness, a human touch is still an important part of the service delivery process, not only because it provides proper solutions for their problems but also because it fulfills the need for feelings of care and personal connection (Makarem et al., 2009). Indeed, recent conceptual papers have consistently recognized the empathic communication skills of human employees as a competitive advantage over artificial intelligence technology (Huang et al., 2019; Larivière et al., 2017; Pedersen, 2021; Solnet et al., 2019). In this study, we provide empirical evidence for this relational cost of using self-service technology, which is no less important than revealing its relational benefit (H1). Therefore, we propose that a customer's perception of a service provider's ability to empathize (i.e., the sense of being cared for and connected to the service provider, which we will refer to as “perceived empathy,” hereafter) increases when customers interact with a frontline employee (vs. self-service technology). This increased sense of perceived empathy eventually results in the more favorable brand evaluation.

H2: Interpersonal contact (vs. self-service technology) increases perceived empathy and subsequently overall brand evaluation.

2.4 The moderating effect of perceived persuasive intent

According to our conceptualization, interpersonal contact with a salesperson activates ambivalent affective responses from customers. While customers feel socially uncomfortable around salespeople, they still need human attention to fulfill their needs for caring and personal connection. Despite the emotional difficulties involved, we still need human contact in the service environment to compensate for the weakness of contact-free technology. Should this be the case, the objective of this study is to identify the moderating factor that can minimize the cost and maximize the benefit of interpersonal contact during service encounters. Specifically, we examine how a customer's access to a salesperson's ulterior persuasive intent impacts the quality of the relationship between the customer and salesperson.

In the traditional service environment, a salesperson plays an important role in persuading customers to make a purchase. For this reason, a salesperson is by definition one who sells, often characterized by his/her strong motivation to sell products. Indeed, in an attempt to influence customers to make a purchase decision, salespeople use various persuasion tactics such as making flattering remarks (Chan & Sengupta, 2010), providing information about limited-time offers (Balachander & Stock, 2009), and being attentive to customers by maintaining physical proximity (Otterbring et al., 2021). After being exposed to such persuasive tactics and becoming aware of the salesperson's ulterior persuasive intent, customers develop persuasion knowledge as a coping strategy to achieve their own consumption goals and avoid being swayed by the salesperson's attempts at persuasion (i.e., persuasion knowledge model; Friestad & Wright, 1994).

This process of using persuasion knowledge to identify and cope with the persuasive intent of a salesperson is emotionally demanding for customers who wish to avoid disappointing salespeople, just as salespeople wish to avoid having their offers rejected by customers (i.e., sales call anxiety; Verbeke & Bagozzi, 2000). To be specific, when exposed to the persuasive intent of a salesperson, customers are reminded of the social exchange characteristics of their relationships with the salesperson. In this social relationship governed by the rule of reciprocity, customers are often pressured by the sense of obligation to return the favor by making a purchase (i.e., social exchange theory; Clark & Mils, 1993). As a result, they feel greater social discomfort from interacting with a salesperson because they fear that they may have to disappoint the salesperson. However, when customers are less exposed to the persuasive intent of a salesperson, the relational cost of interpersonal contact will be reduced or even disappear, such that customers will feel comfortable interacting with a salesperson. Indeed, when the source of social discomfort (i.e., the salesperson's implicit display of persuasive intent) is removed, customers have no reason to avoid interacting with salespeople, who tend to be more reliable and understanding than automated kiosks.

H3: Customer perception of a service provider's persuasive intent moderates the impact of interpersonal contact on overall brand evaluation via social comfort. H3a: When a service provider's ulterior persuasive intent is more accessible to customers, interpersonal contact (vs. self-service technology) decreases social comfort and subsequently overall brand evaluation. H3b: When a service provider's ulterior persuasive intent is less accessible, interpersonal contact (vs. self-service technology) increases social comfort and subsequently overall brand evaluation.

Furthermore, when the persuasive intent underlying the salesperson's behaviors is apparent, customers become suspicious of the salesperson's manipulative intent (i.e., persuasion knowledge model; M. C. Campbell & Kirmani, 2000), and realize that the salesperson is driven by the motivation to fulfill his/her own self-interests rather than by genuine concern for the welfare of customers. Hence, we predict that when the persuasive intent of a service provider is more (vs. less) accessible, the relational benefit of interpersonal contact on perceived empathy will diminish.

H4: Perceived persuasive intent moderates the impact of interpersonal contact on overall brand evaluation via perceived empathy. H4a: When a service provider's ulterior persuasive intent is more accessible, interpersonal contact (vs. self-service technology) decreases perceived empathy and subsequently overall brand evaluation. H4b: When a service provider's ulterior persuasive intent is less accessible, interpersonal contact (vs. self-service technology) increases perceived empathy and subsequently overall brand evaluation.

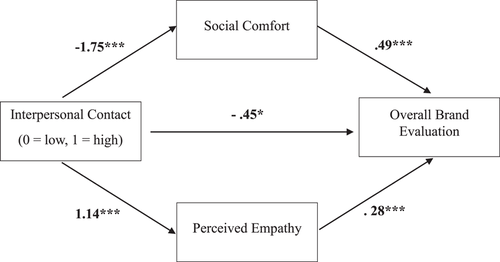

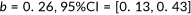

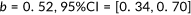

Figure 1 displays the conceptual framework and the hypothesized relationships. In this study, three experimental studies examine the relational cost and benefit of interacting with self-service technology during service encounters. Using a scenario-based experiment, Study 1a reveals the impact of interpersonal contact on overall brand evaluation via social comfort (H1) and perceived empathy (H2). In Study 1b, we eliminate an alternative explanation by experimentally controlling for the impact of customer perception of service providers' persuasive intent. Study 2 expands the findings by exploring the moderating effect of perceived persuasive intent (H3 and H4).

3 STUDY 1a

In an attempt to illuminate the positive and negative consequences of using contact-free technology (vs. human interactions) during service encounters, Study 1a tests the impact of interpersonal contact on overall brand evaluation via social comfort (H1) and perceived empathy (H2).

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Subjects

A total of 250 individuals were recruited from Prolific to participate in the experiment in exchange for ₤1.3. Among them, 56 participants failed to correctly answer the instructional manipulation check (IMC) questions (Oppenheimer et al., 2009). Additionally, the data were assessed for multivariate outliers, using the Mahalanobis distance test (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013), and four multivariate outliers were removed. As a result, the data from 190 respondents (64 males, mean age = 32.23, age range = 18–69) were included in the analysis. The nationalities of the participants were limited to Western countries that use English as an official language (i.e., Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

3.1.2 Design and procedures

The experiment employed a single factor (interpersonal contact: high vs. low) between-subjects design. Participants read one of the two randomly assigned scenarios ( ) and answered the questions. The scenarios were modified from the scenario excerpt from M. C. Campbell and Kirmani (2000), which described a situation in which a participant visits a store of imaginary Brand X in a department store to buy a jacket.

) and answered the questions. The scenarios were modified from the scenario excerpt from M. C. Campbell and Kirmani (2000), which described a situation in which a participant visits a store of imaginary Brand X in a department store to buy a jacket.

In the high interpersonal contact condition, participants were asked to imagine that a salesperson approaches them and makes flattering comments while they are browsing through products. In the low interpersonal contact condition, participants read a scenario that describes them visiting an unmanned digital store of Brand X, where they need to use a tablet PC. In both conditions, we posited a setting in which participants cannot find the perfect product for themselves and eventually leave the store without making a purchase. In this way, we aim to reveal the difference in customer responses to the social interactions with a salesperson versus self-service technology by capturing a realistic service encounter in which the typical in-role behaviors of a salesclerk trigger social discomfort, whereas in an unmanned store setting, the very same situation would not activate social discomfort because customers would not be concerned about disappointing the self-service machine. We also controlled for the effect of technology-related social anxiety by making sure that customers do not experience technology failures in the self-service setting (see Appendix SA).

3.1.3 Measures

Before the manipulation of independent variable, dispositional social anxiety (Leary, 1983; α = 0.94) and technology readiness (Parasuraman & Colby, 2015; α = 0.82) were measured as control variables. After reading the scenario, participants answered the questions measuring dependent variables. We measured overall brand evaluation using five items adapted from Dawar and Pillutla (2000), which were designed to capture brand liking, brand trust, brand quality, brand desirability, and future brand purchase likelihood. We created an overall brand evaluation index by averaging the five measures (α = 0.91). Further, social comfort was measured by the eight items (α = 0.97) adapted from Spake et al. (2003). We also adopted four items from SERVQUAL (Dabholkar et al., 2000; Parasuraman et al., 1994) and an item from eTail Quality Scale (Wolfinbarger & Gilly, 2003) that best represent the concept of perceived empathy (α = 0.90, see Appendix SB for the list of items and their factor loadings). As displayed in Appendix SC, the measurements show good construct validity and reliability.

After completing the dependent measures, participants answered a manipulation check question related to interpersonal contact. The item asked participants to rate the extent to which they agreed with the statement “While I read the scenario, I imagined myself (1 = having zero contact with the salesclerk, 7 = having very much interaction with the salesclerk).” At the end of the survey, participants responded to demographic questions about age, gender, education, and nationality.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Manipulation check

We conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the manipulation of interpersonal contact during the service encounter. The results show that the manipulation was successful, such that participants in the high interpersonal contact condition reported having imagined themselves making a higher level of interpersonal contact ( ) than those in the low interpersonal contact condition (

) than those in the low interpersonal contact condition ( ;

;  ), as intended.

), as intended.

3.2.2 The mediating role of social comfort and perceived empathy

A parallel mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS Model 4 (Hayes, 2018) to explore whether social comfort (H1) and perceived empathy (H2) mediate the impact of interpersonal contact on overall brand evaluation. To enhance the internal validity of the data, we controlled for the effect of dispositional social anxiety (Delacroix & Guillard, 2016), technology readiness (Lin et al., 2007), and age (Simon & Usunier, 2007), which are known to influence self-service technology adoption.3 Using 5000 bootstrapping samples, the procedures showed a significant indirect effect of social comfort ( ) and perceived empathy (

) and perceived empathy ( ; low = 0, high = 1). Specifically, a high level of interpersonal contact during the service encounters led to greater social discomfort (

; low = 0, high = 1). Specifically, a high level of interpersonal contact during the service encounters led to greater social discomfort ( , t = −9.74, p < 0.001), which in turn decreased overall brand evaluation (

, t = −9.74, p < 0.001), which in turn decreased overall brand evaluation ( , t = 7.93, p < 0.001), consistent with H1. Further, participants in the high interpersonal contact condition felt greater perceived empathy toward the company (

, t = 7.93, p < 0.001), consistent with H1. Further, participants in the high interpersonal contact condition felt greater perceived empathy toward the company ( , t = 6.69, p < 0.001), which in turn enhanced overall brand evaluation (

, t = 6.69, p < 0.001), which in turn enhanced overall brand evaluation ( , t = 4.23, p < 0.001; see Figure 2; for standardized coefficients, see Appendix SD), consistent with H2.

, t = 4.23, p < 0.001; see Figure 2; for standardized coefficients, see Appendix SD), consistent with H2.

3.3 Discussion

The results of Study 1a reveal the emotional consequences of a technology-infused service environment, with a focus on social comfort and perceived empathy. On the one hand, using self-service technology offers customers a respite from the social discomfort that they feel in traditional service settings. On the other hand, when customers have direct contact with a frontline employee, interpersonal contact increases perceived empathy, such that customers feel that the company cares about and empathizes with their needs. These results highlight both the dark and bright sides of human contact during service encounters, supporting H1 and H2.

Nevertheless, one may suggest an alternative explanation for the observed effect. In Study 1a, we posited a situation in which participants in the high interpersonal contact condition were highly exposed to a salesclerk's persuasive intent to make sales. It is difficult to tell whether the observed effect is due to differences in the accessibility of ulterior persuasive intent or in the level of human interaction. To eliminate the alternative explanation, we turn to Study 1b, which experimentally controls for the impact of customer perception of service providers' persuasive intent.

4 STUDY 1b

Study 1a provided empirical evidence for the impact of interpersonal contact on overall brand evaluation via social comfort (H1) and perceived empathy (H2). Study 1b aims to replicate these findings and rule out the alternative explanation by experimentally controlling for the impact of being highly exposed to the persuasive intent of service providers.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Subjects

A total of 210 individuals were recruited from Prolific to participate in the experiment in exchange for ₤1.25. Among them, 11 participants were screened out because they failed to correctly answer the IMC questions, and four multivariate outliers were removed, using the Mahalanobis distance test. Eventually, 195 respondents (39 males, mean age = 34.16, age range = 18–74) were included in the analysis. As in Study 1a, the nationalities of the participants were limited to Australia (0.8%), Canada (8.3%), Ireland (9.5%), the United Kingdom (63.1%), and the United States (18.3%).

4.1.2 Design and procedures

As in Study 1a, we manipulated the level of interpersonal contact with scenarios in which participants interact with either a salesclerk ( ) or a tablet PC (

) or a tablet PC ( ). Unlike Study 1a, scenarios were meticulously designed to differ only in the degree of interpersonal contact and to be identical in other respects. That is, participants were exposed to a high level of persuasive intent in both high and low interpersonal contact conditions. Specifically, we manipulated the accessibility of persuasive intent through the persuasive tactics commonly used in practice. In the high interpersonal contact condition, a salesclerk makes a special discount offer (Balachander & Stock, 2009), in addition to making flattering remarks (Chan & Sengupta, 2010), maintaining close distance, and being attentive to customers' every move (Otterbring et al., 2021). In the low interpersonal contact condition, a nearby tablet PC shows a pop-up message that compliments a participant's good taste in fashion for having chosen the particular product and delivers the information about the limited-time discount.

). Unlike Study 1a, scenarios were meticulously designed to differ only in the degree of interpersonal contact and to be identical in other respects. That is, participants were exposed to a high level of persuasive intent in both high and low interpersonal contact conditions. Specifically, we manipulated the accessibility of persuasive intent through the persuasive tactics commonly used in practice. In the high interpersonal contact condition, a salesclerk makes a special discount offer (Balachander & Stock, 2009), in addition to making flattering remarks (Chan & Sengupta, 2010), maintaining close distance, and being attentive to customers' every move (Otterbring et al., 2021). In the low interpersonal contact condition, a nearby tablet PC shows a pop-up message that compliments a participant's good taste in fashion for having chosen the particular product and delivers the information about the limited-time discount.

4.1.3 Measures

After reading the scenario, participants answered the questions measuring dependent variables. We used the same procedures and measures as in Study 1a, including the index of overall brand evaluation ( ), social comfort (

), social comfort ( ), perceived empathy (

), perceived empathy ( ), and technology readiness (

), and technology readiness ( ). We also measured store attitude (Yoo et al., 1998;

). We also measured store attitude (Yoo et al., 1998;  ) and customer service experience (Klaus, 2015; Kuppelwieser & Klaus, 2021;

) and customer service experience (Klaus, 2015; Kuppelwieser & Klaus, 2021;  ) as relevant dependent variables that can influence the affective aspect of service encounters.4

) as relevant dependent variables that can influence the affective aspect of service encounters.4

Participants then answered manipulation check questions, which pertained to their perceptions of the level of interpersonal contact and the accessibility of persuasive intent. We measured perceived persuasive intent with an item adapted from Van Noort et al. (2012). Specifically, in the high (vs. low) interpersonal contact condition, participants read the statement “Pat, the salesclerk, is eager to persuade you to buy the product. (The pop-up message from the tablet PC is created to persuade customers like you to buy the product),” and indicated the extent of their agreement on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). At the end of the survey, participants responded to demographic questions about age, gender, education, and nationality.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Manipulation and confound checks

The manipulation of interpersonal contact was effective. The results of a one-way ANOVA on the interpersonal contact measure show that participants reported imagining themselves making a higher level of interpersonal contact in the high (vs. low) interpersonal contact condition ( vs.

vs.  ;

;  ). Furthermore, we ran a separate one-way ANOVA on persuasive intent to eliminate the possible confound. The results confirm that there is no significant difference between the two experimental conditions with respect to perceived persuasive intent (

). Furthermore, we ran a separate one-way ANOVA on persuasive intent to eliminate the possible confound. The results confirm that there is no significant difference between the two experimental conditions with respect to perceived persuasive intent ( ). Participants in both high and low interpersonal contact conditions reported being highly exposed to marketing tactics intended to persuade them to buy the products.

). Participants in both high and low interpersonal contact conditions reported being highly exposed to marketing tactics intended to persuade them to buy the products.

4.2.2 The mediating roles of social comfort and perceived empathy

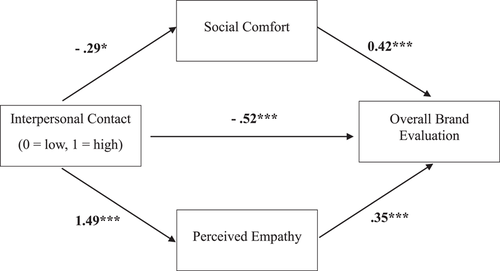

The results of a bootstrapping analysis (PROCESS Model 4; 5000 resample; Hayes, 2018) with technology readiness and age as covariates showed a significant indirect effect of social comfort ( ) and perceived empathy (

) and perceived empathy ( ; low = 0, high = 1). Specifically, a high level of interpersonal contact during the service encounters decreased social comfort (

; low = 0, high = 1). Specifically, a high level of interpersonal contact during the service encounters decreased social comfort ( , t = −5.88, p < 0.001) and in turn decreased overall brand evaluation (

, t = −5.88, p < 0.001) and in turn decreased overall brand evaluation ( = 0.33, t = 5.17, p < 0.001), consistent with H1. The results also supported H2, showing that participants in the high interpersonal contact condition thought more highly of the company's ability to empathize with customer needs (

= 0.33, t = 5.17, p < 0.001), consistent with H1. The results also supported H2, showing that participants in the high interpersonal contact condition thought more highly of the company's ability to empathize with customer needs ( , t = 4.86, p < 0.001), and in turn evaluated the brand more favorably (

, t = 4.86, p < 0.001), and in turn evaluated the brand more favorably ( , t = 4.78, p < 0.001; see Figure 3; for standardized coefficients, see Appendix SD).

, t = 4.78, p < 0.001; see Figure 3; for standardized coefficients, see Appendix SD).

4.3 Discussion

Study 1b replicates the findings from Study 1a while ruling out the alternative explanation. The results show that customers feel greater social discomfort when a salesclerk is eager to persuade them to buy a product, whereas persuasive messages from a tablet PC are considered relatively less burdensome. These results suggest that the same persuasive message triggers different emotional responses from customers, depending on the type of service agent that delivers the message. Furthermore, we reconfirmed the finding that interpersonal contact has a positive impact on customers' perceptions of the company's empathic capabilities. When customers have interactions with frontline employee, they feel that their needs will be met with greater care and empathy in their relationships with the service provider.

5 STUDY 2

Study 2 examines the accessibility of persuasive intent as a moderator that alleviates or enhances the emotional consequences of human interactions during the service encounter (H3 and H4).

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Subjects

A total of 390 individuals were recruited from prolific to participate in the experiment in exchange for ₤1.3. Among them, 20 participants were screened out because they failed to correctly answer the IMC questions, and six multivariate outliers were removed, using the Mahalanobis distance test. In the end, 364 respondents (147 males, mean age = 36.31, age range = 18–74) were included in the analysis. As in prior studies, the nationalities of the participants were limited to Australia (0.8%), Canada (5.2%), Ireland (2.7%), the United Kingdom (77.2%), and the United States (14%).

5.1.2 Design and procedures

Study 2 used a 2 (interpersonal contact: high vs. low) × 2 (persuasive intent: high vs. low) between-subjects design. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. As in prior studies, we manipulated the level of interpersonal contact with scenarios in which participants interact with either a salesclerk ( ) or a tablet PC (

) or a tablet PC ( ). Accessibility of persuasive intent was manipulated through the behaviors of a frontline employee or comments from a tablet PC. As in Study 1b, in the high persuasive intent condition, participants were exposed to persuasive tactics commonly used in marketing practice: making flattering comments (Chan & Sengupta, 2010), providing information about limited-time offers (Balachander & Stock, 2009), and being attentive to customer's every move (Otterbring et al., 2021). In the low persuasive intent condition, a salesclerk/tablet PC responds to customer requests without using such persuasive tactics (see Appendix SA).

). Accessibility of persuasive intent was manipulated through the behaviors of a frontline employee or comments from a tablet PC. As in Study 1b, in the high persuasive intent condition, participants were exposed to persuasive tactics commonly used in marketing practice: making flattering comments (Chan & Sengupta, 2010), providing information about limited-time offers (Balachander & Stock, 2009), and being attentive to customer's every move (Otterbring et al., 2021). In the low persuasive intent condition, a salesclerk/tablet PC responds to customer requests without using such persuasive tactics (see Appendix SA).

5.1.3 Measures

After reading the scenario, participants answered the questions measuring dependent variables. We used the same procedures and measures as in prior studies, including the index of overall brand evaluation ( ), social comfort (

), social comfort ( ), perceived empathy (

), perceived empathy ( ), and technology readiness (

), and technology readiness ( ).

).

After completing the dependent measures, participants answered manipulation check questions and rated their perceptions of the level of interpersonal contact and accessibility of persuasive intent during the service encounter. Finally, participants responded to demographic questions about age, gender, education, and nationality.

5.2 Results

5.2.1 Manipulation checks

The manipulations of interpersonal contact and persuasive intent were effective. The results of one-way ANOVA on the interpersonal contact measure showed a significant main effect of interpersonal contact ( ), such that participants reported a higher level of interpersonal contact in the high (vs. low) interpersonal contact condition (

), such that participants reported a higher level of interpersonal contact in the high (vs. low) interpersonal contact condition ( vs.

vs.  ). Furthermore, results of one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of accessibility of persuasive intent (

). Furthermore, results of one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of accessibility of persuasive intent ( ), such that participants reported being more highly exposed to marketing tactics intended to persuade them to buy products when these participants were in the accessible condition rather than in the less accessible condition (

), such that participants reported being more highly exposed to marketing tactics intended to persuade them to buy products when these participants were in the accessible condition rather than in the less accessible condition ( ).

).

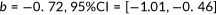

5.2.2 The mediating roles of social comfort and perceived empathy

The results of a mediation analysis with technology readiness and age as covariates confirmed a significant indirect effect of social comfort ( ) and perceived empathy (

) and perceived empathy ( ) in the relationship between interpersonal contact (low = 0, high = 1) and overall brand evaluation. Specifically, a high level of interpersonal contact during the service encounters led to greater social discomfort among customers (

) in the relationship between interpersonal contact (low = 0, high = 1) and overall brand evaluation. Specifically, a high level of interpersonal contact during the service encounters led to greater social discomfort among customers ( , t = −1.98, p < 0.05), and in turn had a detrimental impact on their evaluations of the brand (

, t = −1.98, p < 0.05), and in turn had a detrimental impact on their evaluations of the brand ( , t = 11.43, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Further, participants in the high interpersonal contact condition perceived greater empathy from the service provider (

, t = 11.43, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Further, participants in the high interpersonal contact condition perceived greater empathy from the service provider ( , t = 12.24, p < 0.001), and in turn made more favorable evaluations of the brand (

, t = 12.24, p < 0.001), and in turn made more favorable evaluations of the brand ( , t = 7.90, p < 0.001; see Figure 4), consistent with H2.

, t = 7.90, p < 0.001; see Figure 4), consistent with H2.

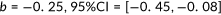

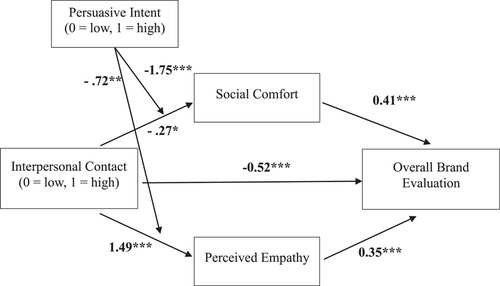

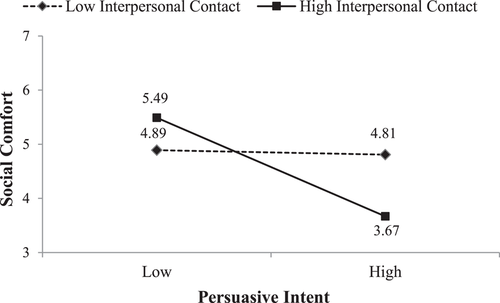

5.2.3 The moderating effect of accessibility of persuasive intent

We conducted a mediated moderation analysis (Hayes, 2018; PROCESS Model 8; 5000 resamples) with covariates of technology readiness and age. The results showed a significant interaction effect of interpersonal contact (low = 0, high = 1) × persuasive intent (low = 0, high = 1) on overall brand evaluation via social comfort ( ) and perceived empathy (

) and perceived empathy ( ), supporting H3 and H4. As illustrated in Figure 5, interpersonal contact and persuasive intent had a significant interaction effect on perceived social comfort (

), supporting H3 and H4. As illustrated in Figure 5, interpersonal contact and persuasive intent had a significant interaction effect on perceived social comfort ( ) and empathy (

) and empathy ( ), which in turn significantly influenced customers' evaluations of the brand, respectively.

), which in turn significantly influenced customers' evaluations of the brand, respectively.

To look more deeply into the moderation effect, we present a graph plotting significant interactions using the estimates obtained from the simple slope analyses. Figure 6 shows that when the service provider's persuasive intent was highly accessible, interpersonal contact decreased the social comfort felt during the service encounter. However, the pattern of this result was reversed in the less accessible condition: participants felt more comfortable when they had interactions with a frontline employee (vs. a self-service machine). These results suggest that there is a chance to overcome the downside of the traditional service environment by changing the behaviors of salespeople.

In addition to reconfirming the finding that interpersonal contact improves customer evaluations of the company's level of care and empathy, we discovered the fact that sales-pressing persuasive gestures from a salesclerk reduce the beneficial effect of human contact on perceived empathy (see Figure 7).

5.3 Discussion

Study 2 not only replicates the findings from the previous studies but also shows that accessibility to persuasive intent moderates the impact of interpersonal contact on brand evaluation. Specifically, Study 2 provides further evidence of the relational benefit and cost of technology-involved service encounters: that is, using self-service technology increases social comfort and decreases perceived empathy, compared to human interactions. More importantly, Study 2 provides insights that can help in managing service personnel. The study demonstrates the moderating effect of perceived persuasive intent and shows that greater empathy on the part of service personnel can compensate for the weaknesses of self-service technology. The results also reveal that the beneficial impact of interpersonal contact on perceived empathy declines as the persuasive intent of a service provider becomes accessible. More interestingly, the results show that the detrimental impact of human interactions on social comfort disappears when salespeople cease their attempts to persuade customers to make purchases. Indeed, customers feel even more comfortable interacting with a frontline employee than using self-service technology when the persuasive intent is not accessible, suggesting that customers feel uncomfortable interacting with a salesperson because of the social nature of service encounters. A salesperson's display of persuasive intent highlights the social exchange characteristics of the service interaction and increases a sense of obligation to make a purchase. Consequently, customers feel uncomfortable when they have to leave the store empty-handed, to the disappointment of a salesperson. When the salesperson does not use persuasive tactics, however, service interactions become less stressful because the main source of social discomfort disappears.

6 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, self-service technology was widely adopted by marketing practitioners not only as a means to achieve cost efficiency but also as an effective marketing tool. Although past research has investigated antecedents, consequences, and boundary conditions of technology-associated customer behaviors, it might be useful to compare the relational cost and benefit of self-service machines and salespeople. By exploring the tradeoffs between self-service machines and salespeople, our research offers an explanation for the change in consumer needs in the technology-infused service environment.

6.1 Theoretical implications

Our research not only reveals that social comfort is an underlying mechanism behind customer preference for self-service technology over human contact but also recognizes that self-service technology suffers from an inability to empathize with customer needs. In addition to exploring the relational benefit and cost of contact-free technology, our research identifies the moderating effect of a service provider's persuasive intent. The findings of our study have several theoretical implications.

First, our research contributes to the self-service technology literature by exploring the role of social discomfort as a relational cost of human interactions that motivate customers to prefer self-service technology over human contact. Based on the social exchange theory, we identified the relational benefit of using self-service technology to spare customers the trouble of interacting with a salesperson, which eventually improves overall brand evaluation in a situation where typical salesperson behaviors might increase social discomfort.

Second, our research illuminates the relational cost of using self-service technology by demonstrating the indirect effect of perceived empathy. That is, customers think highly of a service provider's ability to empathize with their needs, which in turn results in more favorable brand evaluations. This finding contributes to the literature by extending the scope of prior research which has addressed this issue at a conceptual level or in the traditional setting. In this way, the present research reveals that perceived empathy plays an important role even in technology-infused service environments as a competitive strength of human contact that complements the weakness of self-service technology.

Third, this study sheds additional light on customers' use of persuasion knowledge by demonstrating the moderating effect of the perceived persuasive intent of salespeople. Interpersonal contact decreases social comfort when the persuasive intent is highly accessible. When the persuasive intent is less accessible, however, the relational cost of human interactions disappears, and customers feel socially comfortable interacting with salespeople. While prior research mainly focused on the cognitive aspect of the use of persuasion knowledge in one-time encounter, we offer a new perspective on the role of self-service technology as a buffer against the activation of persuasion knowledge and its negative emotional consequence (i.e., social discomfort), which eventually impacts customer-brand relationships in the long run.

6.2 Practical implications

The findings also provide several implications for marketing and human resources managers. Specifically, the results reveal the underlying mechanism behind the growing customer desire for zero contact by demonstrating that customers feel social discomfort even from in-role behaviors of salespeople. Frontline employees need to understand that some customers dislike aggressive attempts to provide brand information but appreciate caring and empathic personal connections with brand representatives.

Considering that human contact is still an inevitable part of the service environment, our finding has an important implication for managers of frontline employees. Customers are found to feel comfortable interacting with salespeople when the persuasive intent is less accessible, suggesting that there is a chance to overcome the downside of the traditional service environment. We suggest that brand managers work closely with their human resources and operations groups to hire employees with high emotional intelligence and to advise these employees against the negative emotional consequences of aggressive persuasion tactics.

Finally, Study 2 reveals that a customer's affective response toward a persuasive message differs depending on the type of the sales agent. Whereas exposure to a salesperson's persuasive intent decreases social comfort among customers and eventually diminishes the persuasive effect of the message, a machine-delivered persuasive message is perceived as neutral information and has no significant impact on social discomfort and overall brand evaluation. This finding suggests that managers can reduce the negative consequences of a persuasive message by delivering it through self-service technology rather than a salesperson. Future research can probe this difference in customers' perceptions of persuasive intent among more advanced types of artificial intelligence technology such as chatbots and service robots, which are considered effective marketing tools that can complement human labor during the pandemic and afterward.

6.3 Limitations and future research

We also recognize several limitations that provide room for future research. First, future research may extend our findings by examining the relational cost and benefit of interpersonal contact in other service settings and among customers with individual differences (e.g., high or low prior knowledge). For instance, it will be worthwhile to explore the moderating effect of service complexity or product type (e.g., luxury vs. nonluxury5) and figure out the particular service areas where customers would prefer self-service technology to avoid social discomfort from human contact.

Second, whereas our research examined the salesperson behaviors and attitudes that trigger social discomfort among customers, further research could investigate the impact of other easily manageable salesperson characteristics (e.g., the brand-aligned physical appearance of a salesperson).

Third, the experiments in the current research were conducted with participants from Western countries. Future research can extend our findings by exploring the moderating effect of cultural differences. Such differences may influence the extent to which interpersonal contact activates social discomfort, such that customers from individualistic (vs. collectivistic) cultures are less likely to feel socially uncomfortable around salespeople with self-concepts that are independent from their group identities (Kitayama & Markus, 1999).

Fourth, although this study has focused on the negative impact of digital technology that increases social discomfort in weak-tie relationships, it would also be interesting to explore the positive aspect of network privatism that technology-mediated communication can enhance social bonds in strong-tie relationships. For instance, future research can extend our findings by examining the impact of relationship norms (communal vs. exchange) on social discomfort among digital consumers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the Institute of Management Research, Seoul National University.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data will be available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1 Spake et al. (2003) used the term “consumer comfort” to describe the specific social emotion during the service encounter. This term is too broad and may mislead readers as including a customer's sense of contentment toward an efficiently and aesthetically designed service environment, whereas it specifically refers to a state of mind free of interaction-induced anxiety. For this reason, we use the term “social comfort” instead of “consumer comfort.”

- 2 While the types of self-service technology include online commerce and mobile application service, we focus on interactive kiosks located in offline unmanned retail stores to examine the impact of interpersonal contact while controlling for the difference between online and offline service environments and considering the growing interest in integrating physical and digital experience by launching offline digital stores (Linzbach et al., 2019).

- 3 Technology readiness had a significant effect on social comfort (b = 0.25, t = 2.35, p < 0.05). However, there was no significant effect of social anxiety or age on the dependent variables. For this reason, we did not include social anxiety in the subsequent analyses. The null effect of age may be due to the fact that we controlled for the impact of anxiety arising from technology failures or low level of technology readiness. This finding suggests that even elderly customers would not endure social discomfort once they get familiar with using self-service technology or are provided with more user-friendly interfaces. Considering the growing need for contact-free service environments and the development of more advanced, easy-to-use self-service machines, these results have practical implications for marketers in understanding the technology adoption by elderly consumers.

- 4 Separate mediation analyses with store attitude (i.e., SA) and customer service experience (i.e., EXQ) as dependent variables revealed the significant indirect effect of social comfort (

) and perceived empathy (

) and perceived empathy ( ). Also, we found the significant serial mediation effect (b = − 0.33, 95% CI = [− 0.50, −0.19]) of “interpersonal contact → customer service experience → store attitude → overall brand evaluation,” such that interpersonal contact has a negative impact on customer service experience (b = − 0.75, t = − 4.64, p < 0.001), which in turn results in less favorable store attitude (b = 0.82, t = 13.52, p < 0.001) and eventually decreases overall brand evaluation (b = 0.54, t = 9.54, p < 0.001). This finding suggests that customer service experience and store attitude serve similar roles that social comfort and perceived empathy play in customer–brand relationships. Furthermore, store attitude is highly correlated with overall brand evaluation (

). Also, we found the significant serial mediation effect (b = − 0.33, 95% CI = [− 0.50, −0.19]) of “interpersonal contact → customer service experience → store attitude → overall brand evaluation,” such that interpersonal contact has a negative impact on customer service experience (b = − 0.75, t = − 4.64, p < 0.001), which in turn results in less favorable store attitude (b = 0.82, t = 13.52, p < 0.001) and eventually decreases overall brand evaluation (b = 0.54, t = 9.54, p < 0.001). This finding suggests that customer service experience and store attitude serve similar roles that social comfort and perceived empathy play in customer–brand relationships. Furthermore, store attitude is highly correlated with overall brand evaluation ( ), social comfort (

), social comfort ( ), and perceived empathy (

), and perceived empathy ( ), while customer service experience is highly correlated with overall brand evaluation (

), while customer service experience is highly correlated with overall brand evaluation ( ), social comfort (

), social comfort ( ), and perceived empathy (

), and perceived empathy ( ). There is also a high correlation between store attitude and customer service experience (

). There is also a high correlation between store attitude and customer service experience ( ). These results raise concerns for the potential multicollinearity when these variables are added to the original model. Therefore, as suggested in Lemon and Verhoef (2016), we will focus on more established service quality indicators of perceived empathy, social comfort, and overall brand evaluation in the subsequent study (1) to focus on more specific affective experiences of customers, (2) to examine the long-term customer–brand relationship, and (3) to prevent the multicollinearity issue.

). These results raise concerns for the potential multicollinearity when these variables are added to the original model. Therefore, as suggested in Lemon and Verhoef (2016), we will focus on more established service quality indicators of perceived empathy, social comfort, and overall brand evaluation in the subsequent study (1) to focus on more specific affective experiences of customers, (2) to examine the long-term customer–brand relationship, and (3) to prevent the multicollinearity issue. - 5 Following a reviewer's advice, we conducted a mediated moderation analysis in a new study that examined the interaction effect of product type (luxury vs. fast-fashion brand) and interpersonal contact (high vs. low) on dependent variables of overall brand evaluation, store attitude, and customer service experience via social comfort and perceived empathy. The results reconfirmed the significant indirect effect of social comfort (b = −0 .38, 95% CI = [− 0.58, − 0.21]) and perceived empathy (b = .19, 95% CI = [0.09, 0.31]) on overall brand evaluation. More importantly, we found a significant interaction effect of product type x interpersonal contact on customer service experience (b = − 0.44, t = −2.01, p < 0.05). Specifically, the quality of customer service experience decreases when participants interact with a salesperson (vs. self-service machine). This negative impact of interpersonal contact on customer's evaluations of service experience quality is stronger in the luxury (vs. nonluxury) consumption condition. These findings suggest that aggressive persuasion tactics from a salesperson have more detrimental impacts on customers' affective experiences, especially for luxury brands. When technology readiness and age are added as covariates, the interaction effect is marginally significant (b = − 0.42, t = −1.93, p = 0.055). Future research could extend our findings by examining the underlying mechanism and boundary condition of the results. For more details about the method, manipulation check, and main results, see Appendix SE.