What makes products look premium? The impact of product convenience on premiumness perception

Abstract

This study examines the impact of product convenience on premiumness perception. A comparative survey and four experiments confirm that products viewed as convenient are perceived as more premium than their less convenient counterparts. This effect persists even when the overall quality and preference of the convenient product is equivalent to a less convenient counterpart. The convenience–premiumness relationship is driven by perceptions of convenient products' manufacturers being more customer-oriented. Moreover, the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation is stronger for consumers with higher productivity orientation, which suggests that the benefits obtained from convenient products are valued more by those who value efficient time management. Furthermore, our results confirm that convenience, besides influencing premiumness perceptions of the product, also positively influences downstream consumer behavior.

1 INTRODUCTION

Convenience has become increasingly important for consumers (Reimers & Chao, 2014), as the number of dual-income households has increased and individuals are working longer hours (Alreck & Settle, 2002). This has augmented perceptions of time scarcity (Hamermesh & Lee, 2007) and has led these “money-rich/time-poor” consumers (Keinan et al., 2019) to seek time-saving and easy-to-use products. Recently, consumers have cited convenience as the primary reason for adopting new products (Zimmermann et al., 2020). In his New York Times article “The Tyranny of Convenience,” Wu (2018) argues that convenience significantly influences consumer decisions, but its importance tends to be underestimated because we often take it for granted. As Twitter cofounder Evan Williams stated (Wu, 2018), “Convenience decides everything.” Convenience undoubtedly affects our decisions, trumping what we imagine to be our true preferences (e.g., I prefer to brew my own coffee, but because Starbucks' instant coffee is so convenient, I hardly ever do what I “prefer”). Most often, consumers are willing to pay more for convenient products or services. For example, YouTube Premium, which provides ad-free access to its content for a monthly fee, has recently been gaining ground among YouTube users.

According to Farquhar and Rowley (2009), although convenience has been frequently discussed in literature on consumer choice, researchers have paid insufficient attention to how and why convenience affects consumers' product evaluations. Following Farquhar and Rowley's (2009) suggestion, there has since been a steady stream of research on convenience. However, as summarized in Table 1, existing literature has examined convenience mainly in service sector contexts (e.g., Jebarajakirthy & Shankar, 2021; Roy et al., 2018) and shopping experiences (e.g., Reimers & Chao, 2014; Sohn et al., 2017; van Esch et al., 2021). Regarding tangible goods, research on convenience has been limited to technological products (Chau et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2017). However, consumers seek convenience in various aspects of their everyday lives, as evidenced by the popularity of home appliances such as air fryers and dishwashers. Indeed, consumers are more familiar with and frequently use tangible products that are not technologically complicated. Moreover, consumers in most industrialized societies are increasingly perceiving a “time famine,” further increasing their search for convenient and time-saving products. Thus, understanding how convenience influences the perceived premiumness of products that are familiar to consumers would provide practical implications to marketers seeking to position these familiar products as premium choices in the market.

| Paper | Research domain | Convenience definition | Key finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pihlström and Brush (2008) | Service: Information and entertainment mobile service | The ease and speed of achieving a task effectively and efficiently, saving time and effort. | Convenience value, along with monetary, emotional, and social value positively affect willingness to pay premium price, repurchase intention, and word of mouth. |

| Hsu et al. (2010) | Service: Home delivery service | Consumers' perception of the extent to which they are saving time and effort by buying or using a service. | Service quality is positively related with customer loyalty, and this relationship is stronger when service convenience is greater. |

| Nguyen et al. (2012) | Service: Service in retail showroom and concert | Consumers' perception of the extent to which they are saving time and effort by buying or using a service. | As service convenience increases, the relationships between perceived service quality and its subdimensions (interaction, environment, and outcome quality) become stronger. |

| Orel and Kara (2014) | Service: Self-service technologies in supermarkets | The extent to which customers perceive that the operating hours of self-service technologies (SSTs) are convenient and that the firm's SSTs are easy to reach. | Self-checkout systems' convenience contributes to customer satisfaction and loyalty. |

| Benoit et al. (2017) | Service: Service at a retailer in the consumer and packaged goods sector | The extent to which consumers feel that minimal time and effort are required during each phase of the service encounter—decision, access, search, transaction, and after-sales convenience. | Service convenience positively affects customer satisfaction, and this relationship is moderated both by psychographic and sociodemographic factors. |

| Roy et al. (2018) | Service: Retail banking and mobile services | The extent to which consumers feel that minimal time and effort are required during each phase of the service encounter—decision, access, transaction, benefit, and postbenefit convenience | Service convenience, perceived quality, and perceived fairness positively affect customer engagement. |

| Shahijan et al. (2018) | Service: Cruise traveling experience | Consumers' perception of the extent to which they are saving time and effort by buying or using a service. | Service convenience influences overall customer satisfaction and revisit intentions. |

| Jebarajakirthy and Shankar (2021) | Service: Mobile banking adoption intention | The extent to which consumers feel that minimal time and effort are required during each phase of the service encounter—access, search, evaluation, transaction, benefit, and postbenefit convenience. | Access, transaction, benefit, and postbenefit convenience are key influences on mobile banking adoption intentions. |

| Beauchamp and Ponder (2010) | Shopping: Brick-and-mortar stores and online shopping | Consumers' perceptions of the shopping experience's speed and ease during each phase—access, search, transaction, and possession convenience. | Online shoppers have more favorable perceptions of access, search, and transaction convenience relative to in-store shoppers. |

| van Esch et al. (2021) | Shopping: Artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled checkouts | No specific definition has been provided. | Perceived shopping convenience leads to favorable attitudes and higher purchase intention. |

| Sohn et al. (2017) | Shopping: Shopping experience in mobile online shops | The extent to which shopping is effortless or costless. | Convenient shopping experiences leads to greater customer satisfaction. |

| Reimers and Chao (2014) | Shopping: Recreational shopping trip | Consumers' perceptions of the shopping experience's speed and ease during each phase—time, spatial, access, and parking convenience. | Overall convenience and the time-saving and distance-minimizing properties of the shopping experience influence satisfaction. |

| Lim and Kim (2011) | Shopping: TV shopping | No specific definition has been provided. | Lack of shopping mobility makes consumers perceive TV shopping convenient, and such perceived convenience leads to greater satisfaction with TV shopping. |

| Chang et al. (2012) | Technology-oriented product: Mobile English learning technology | The extent to which individuals can perform a task at any time or place with ease. | Perceived convenience is an antecedent of individuals' acceptance of English mobile learning. |

| Zhang et al. (2017) | Technology-oriented product: Healthcare wearable technology | Consumers' perceptions of ease when using wearable healthcare technology in terms of time, place, and execution. | Perceived convenience (a technical attribute of wearable healthcare technology) positively affects perceived usefulness and adoption intentions. |

| Chau et al. (2019) | Technology-oriented product: Healthcare wearable technology | Consumers' perceptions of ease when using a product in terms of time, place, and execution. | Perceived convenience and irreplaceability are key predictors of perceived usefulness, which in turn positively influences adoption intentions. |

| Mathew and Soliman (2021) | Technology-oriented product: Digital content marketing (DCM) | Consumers' perceptions of ease when using information technology in terms of time, place, and execution. | Perceived convenience positively affects purchase intentions and actual purchases of tourism products using DCM. |

Our primary argument is that convenience leads to enhanced perceptions of premiumness. Premiumness refers to the extent to which products' quality and price appear superior to those of alternative products (Quelch, 1987; Velasco & Spence, 2019). While one can argue that any desirable product attribute can lead to greater preference and perceived premiumness, we contend that convenience is special in this regard. Compared to other product attributes such as durability or innovativeness, we expect the relationship between convenience and premiumness to be stronger, especially among consumers who are highly productivity-oriented. Next, we provide detailed theoretical justification for this proposition, delineate our primary hypotheses, and describe the five studies including a pretest conducted to test these hypotheses.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Convenience and perceptions of premium status

We derive our definition of convenience from previous studies examining its role in various consumption contexts. Convenience represents one functional value (Sweeney & Soutar, 2001; Zabkar & Hosta, 2013), which refers to perceived benefits from products' functional, utilitarian, or physical features (Sheth et al., 1991). Functional values include convenience, cost-efficiency, safety, and performance (Zabkar & Hosta, 2013). A product's functional value is evaluated based on its quality, durability, and reliability (Sheth et al., 1991). Convenience has distinctive attributes compared to other functional values as it focuses on the amount of time and effort saved from using the product or service. Consider the example of a gas oven. The oven can be convenient or inconvenient in terms of one-touch operations or faster cooking time. However, the oven can have several additional benefits (higher temperature capacity, larger volume, etc.). While all the listed benefits of the oven can be classified under “functional value,” only some of them may relate directly to convenience. We argue that convenience has a stronger impact on premiumness perceptions than other non-convenience-related functional benefits of a product.

Table 1 shows that relevant previous studies can be categorized into three groups—convenience of service, shopping, and technological products—each providing a slightly different definition of convenience. Research examining service convenience has relied mostly on Berry et al. (2002) five-factor convenience model including decision, access, transaction, benefit, and postbenefit convenience. Berry et al. (2002) have defined service convenience as the extent to which consumers feel that they are saving time and effort while making a purchase decision, initiating contact and finalizing the transaction with the service firm, receiving core benefits of a service, and maintaining contact with the service firm and resolving purchase-related issues. Previous studies on service convenience have modified some dimensions of Berry et al.'s (2002) service convenience conceptualization. For example, Benoit et al. (2017) replaced benefit convenience and postbenefit convenience with search convenience and after-sales convenience, and Jebarajakirthy and Shankar (2021) replaced decision convenience with search convenience and evaluation convenience. Studies on shopping convenience have also employed definitions of convenience similar to that of service convenience, but some have added shopping-specific aspects such as parking convenience (Reimers & Chao, 2014) and possession convenience (Beauchamp & Ponder, 2010). Finally, research on technological product convenience has defined convenience as the extent to which consumers feel that they can perform and complete a task at any time and place with ease. The common thread is saving time and effort in exploring, buying, and using a product or service (Berry et al., 2002; L. G. Brown, 1989). In other words, irrespective of its function or benefit, when a product or service is easy to use and reduces emotional, physical, and cognitive burdens, consumers perceive it as convenient. Products and services are acquired to achieve specific consumer goals. These goals could be hedonic (e.g., entertainment through watching TV shows; positive arousal through a thrilling car ride) or utilitarian (e.g., washing dishes using a dishwasher; watering the lawn using a water hose). All products and services require some amount of time and effort exertion by the consumer in order for this goal to be achieved. Convenience is that attribute of the product and service which results in a consumer having to spend less time and effort for the product and service to achieve its goal. Along these lines, early foundational work on product convenience has also conceptualized convenience as a time/effort dependent construct (Yale & Venkatesh, 1986). Based on prior research, we define convenience as consumers' perception that they can experience optimal value from a product while investing the least time and effort.

We suggest that products attain a more premium status in the market when consumers perceive them as more convenient. Although there has been scant evidence that shows the relationship between convenience and premiumness, Pihlström and Brush's (2008) finding seems to provide some support for our main argument. They examined information and entertainment mobile service users' value perception and its impact on behavioral outcomes including willingness to pay premium price. Convenience was suggested as one of the values along with monetary, emotional and social value, and was shown to be positively associated with willingness to pay premium price. This finding appears to indicate that convenience contributes to perception of service's superiority. But what is so special about convenience, however? Just as convenience enhances perceptions of quality, so could any other attribute such as esthetics, safety, reliability. Indeed, Pombo and Velasco (2021) showed that symmetric design affects premiumness perception of the brand. Giving importance to any attribute other than convenience could therefore also enhance a product's premium status. Responding to this valid question, we argue that convenience has a greater impact compared to most of these other attributes. Thus, while any attribute can enhance product preference and perceived quality, we posit that convenience will especially enhance a product's premium status. The primary reason for this special convenience–premiumness relationship is rooted in consumers' status-signaling behavior and increased valuation of time-saving and convenience.

The traditionalist view of conspicuous consumption (Veblen, 1994) suggests that consumers seek status through ownership and display of material possessions or positional goods. However, recent findings have questioned such a simplistic account of status enhancement through consumption. Contemporary research has revealed unorthodox trends in consumers' status-signaling behavior. Today, blatant displays of wealth often backfire (McFerran et al., 2014; Srna et al., 2020). Instead of ostentatious displays of material possessions, consumers often seek out more contemporary and practical strategies for signaling high status. For instance, in his tour de force exposition of American social classes, Frank (2013) discusses how wealthy individuals often choose to drive the low-cost Prius rather than the expensive Hummer. Other such unconventional examples include purchasing goods with inconspicuous logos (Berger & Ward, 2010), nonconformity to social norms (Bellezza et al., 2014), consuming experiences instead of material goods (Valsesia & Diehl, 2017), “reverse snobbery” or minimalistic consumption (Bellezza & Berger, 2020; Frank, 2013), and consuming sustainability-focused products (Amatulli et al., 2021). We posit that such unorthodox signaling strategies may also trickle down to interattribute weighting in product evaluation. Instead of seeking premiumness through product size, feature-richness, or flashiness, consumers may often resort to exhibiting preference for “smarter” attributes such as convenience and ease of use. This aligns with findings that displaying temporal busyness and opting for time-saving products are very effective strategies to signal high status (Bellezza et al., 2017). Social norms about spending money to save time are also shifting. Instead of frowning upon it as a sign of laziness, many now view time-saving purchases as a prudent investment in long-term happiness, well-being and social connectivity (Keinan et al., 2019; Mogilner, 2019; Whillans et al., 2017).

Some of this added focus on convenience and time saving may also result from the long-term trend of consumers in industrialized societies feeling increasingly time-starved (Gross, 1987; Keinan & Kivetz, 2011). While most longitudinal time-use surveys suggest that average work hours have actually decreased over the last several decades, growing commitment to leisure and family time have increased perceptions of “time famine” (Hamermesh & Lee, 2007). Therefore, consumers likely prefer perceived time-saving products especially strongly, which may also enhance perceptions of products' premiumness. In a similar vein, research in consumer decision making has modeled humans as “cognitive misers” (Fiske & Taylor, 1991) who prefer simpler, less effortful ways to solve problems. This disposition would lead to a stronger preference for intuitive, easy-to-use products (Wu, 2018).

Accordingly, we propose that convenience-related aspects of the product will enhance its premium status. Thus, we propose our first hypothesis:

H1: Products that are perceived as more convenient are perceived as more premium than those that are perceived as less convenient.

2.2 Perceived customer orientation

We propose that convenient products are perceived as premium because customers consider them as highly customer-oriented. Perceived customer orientation refers to the extent to which customers believe that an organization aims to develop and implement a strategy to satisfy their needs (T. J. Brown et al., 2002; Theoharakis & Hooley, 2008). As the social value and economic logic of building sustainable long-term customer–company relationships has increased recently (Narver & Slater, 1990; Shapiro, 1988), appearing more customer-oriented has gained newfound importance. More so than esthetically appealing or durable products, convenient products likely make consumers believe that the companies manufacturing them are highly invested in their customers. Such customer-oriented companies appear to fully understand what customers want and design products catering to these needs. In these hectic times, consumers expect products and services that are easy to use; so, when they find one that is convenient, they feel as though the brand fully understands their needs and strives to satisfy them. Unlike products that are visually superior or more durable, creating a convenient product requires a company to develop an especially meticulous understanding of consumers' needs, desires, and aspirations (Berry et al., 2002; L. G. Brown, 1989; Farquhar & Rowley, 2009). Succinctly, we argue that offering high-convenience products is a strong indicator of a company's customer orientation.

Customer-oriented products are more likely to be perceived as premium since being attuned to customers' needs and behavior is highly valued and profitably rewarded (Bordoloi, 2004; Gorry & Westbrook, 2011; Harris et al., 2014; O'Brien & O'Toole, 2021), and also creates bonds of social attachment that enhance customer trust and loyalty (Fournier, 1998). As high customer loyalty positively influences consumers' willingness to pay premium prices (Casidy & Wymer, 2016), we can expect a close relationship between level of customer orientation and premiumness of the product.

Additionally, consumers are willing to pay more for products with customized features that fulfill their unique needs (Franke & Piller, 2004; Franke & Schreier, 2008; Schreier, 2006). Likewise, highly customer-oriented products appear more desirable when they fulfill the modern consumer's specific need for convenience. Consequently, consumers perceive products as premium when these products also appear to be strongly customer-oriented. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceived customer orientation of products mediates the relationship between convenience and premiumness perception.

While these first two hypotheses are theoretically interesting, the question of their managerial relevance still remains unanswered. Even if convenience drives premium status, how does that inform managerial action? One can argue that consumers may be willing to pay higher prices for high convenience; but they will also do so for other valued attributes (e.g., reliability, multifunctionality). We argue that convenience has special value in that it disproportionately drives perceptions of customer orientation. Consumers' perception that the company genuinely understands them can pay especially rich dividends. While consumers may purchase products for many reasons, if they believe that the company truly understands their needs, this may result in beneficial behaviors beyond a one-time purchase. Consumers are more likely to spread positive word-of-mouth (Godes & Mayzlin, 2009; Macintosh, 2007) and be more trusting (Bateman & Valentine, 2015; Luo et al., 2008) of companies whom they perceive as more customer-oriented (Brady & Cronin, 2001). Finally, as discussed earlier, we expect that other people will view consumers using more convenient products as having higher social status. Thus, compared to other product features, convenience is likely to have a greater impact on long-term postpurchase behavior. More specifically, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Products perceived as more convenient generate positive spillover effects on word-of-mouth, brand trust, and status signaling.

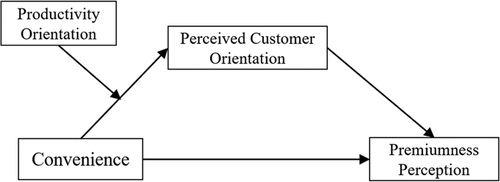

2.3 Productivity orientation

We propose that the impact of convenience on the perceived premium status of products, mediated by perceived customer orientation, will be stronger for consumers with greater productivity orientation. Productivity orientation refers to the degree to which individuals can use their time efficiently (Keinan & Kivetz, 2011). Today, consumers tend to view time as an extremely limited resource (Gross, 1987; Keinan & Kivetz, 2011) and are very invested in making the most of it (Rifkin, 1987). This is consistent with consumers' shifting focus from material to experiential purchases and thus feeling happier about their experiences (Gilovich et al., 2015). Material purchases require money, but experiential purchases require time, which is one of the most important resources. Thus, modern-day consumers are highly interested in making efficient use of time. Air fryers, for example, are gaining popularity among consumers not only because of its healthiness and taste of the food but also the speed and convenience that they provide (Clark, 2019). Highly productivity-oriented consumers seek to achieve more progress in less time (Keinan & Kivetz, 2011). Convenient products, which are easy to use and save users' time and effort, are likely to be assessed more favorably by highly productivity-oriented consumers. These consumers view convenient products as satisfying their productivity needs and thereby perceive customer-oriented products as premium. In contrast, less productivity-oriented consumers are less likely to view convenient products as premium. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis (Figure 1):

H4: Consumers' productivity orientation moderates the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation on the relationship between convenience and perceived premiumness. Specifically, the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation is significant only when productivity orientation is high.

As discussed, we next administered a pretest and conducted four subsequent studies to test our four hypotheses.

3 PRETEST

We conducted a pretest to confirm our main prediction that products' convenience will contribute to perceptions of premiumness. Two hundred and fifty-three undergraduate students (55% female, MAge = 23.05) at a large US public university participated in the study for partial course credit. They indicated the extent to which they value each of the following three different attributes when choosing a product on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not very important, 7 = very important): “good-looking,” “convenient and user-friendly,” and “reliable and long-lasting.” Approximately half of the participants rated the attributes assuming that they were comparing several equally priced products. We informed the other half of the definition of premium products, particularly that they are typically priced higher than the average product. Then, participants rated the importance of these same attributes assuming that they were choosing a premium product. Among the three attributes, ratings of convenience and user friendliness differed significantly across the two conditions such that importance of these attributes were significantly greater for premium products than for nonpremium products (Mpremium = 6.17 vs. Mnonpremium = 5.64; F(1, 251) = 12.699, p < 0.001). Neither of the other two measured product attributes differed significantly across the premium and nonpremium products (good-looking: Mpremium = 5.20 vs. Mnonpremium = 4.98; F(1, 251) = 1.66, p = 0.199; reliable and long lasting: Mpremium = 6.40 vs. Mnonpremium = 6.53; F(1, 251) = 1.14, p = 0.287). This result offers preliminary evidence in support of our main proposition that convenience contributes to products' premiumness above and beyond other important aspects such as esthetic appeal and durability.

4 STUDY 1

In Study 1, we examined whether products' convenience is associated with consumers' perceptions of their premium status. We utilized a laser printer as a stimulus and created hypothetical customer reviews for it.

4.1 Methods and results

We recruited an online panel of 197 individuals from a research firm in South Korea, with seven participants who did not pass the attention check subsequently excluded. The final sample consisted of 190 participants (49.5% female, MAge = 45.64). We asked them to participate in a series of short surveys for monetary compensation. We randomly assigned participants to either a convenience or control condition in a one-factor between-subjects design. We created different customer reviews of a printer from the fictitious brand “XYZ” for each condition. Participants read either a review making the printer appear convenient (e.g., “It can be connected with the Wi-Fi network”) or less convenient (e.g., “It can be connected to my laptop with the cable”). After reading the descriptions (Appendix A), participants answered three items assessing their perceptions of the product's premiumness (Appendix B). We averaged the ratings for the three items to create a composite score that served as a dependent variable. Participants then answered two items, which we averaged to create an overall manipulation check, asking whether the printer in the fictitious consumer review was convenient (Appendix B).

Analysis of the manipulation check revealed that participants in the convenience condition rated the printer as more convenient than did those in the control condition (Mconvenience = 5.27 vs. Mcontrol = 4.09, F(1, 189) = 38.61, p < 0.001). Supporting H1, participants in the convenience condition perceived the printer as more premium than those in the control condition (Mconvenience = 4.55 vs. Mcontrol = 3.48, F(1, 189) = 34.21, p < 0.001).

4.2 Discussion

Study 1 showed that perceived convenience can contribute to a premium image of the product. Participants in the convenience condition rated the product's premiumness significantly greater than those in the control condition. Nevertheless, we can offer an alternative explanation of Study 1's results. While our manipulation successfully altered convenience across the two conditions, it is possible that the perceived overall quality also differed across conditions. In general, consumers are likely to perceive the quality of relatively more convenient products or services as superior to that of less convenient ones (Berry et al., 2002). Thus, greater premiumness ratings in the convenience condition may have been due to differences in perceived quality rather than convenience.

Additionally, because we used the customer reviews as stimuli, participants might have indirectly inferred other product attributes not mentioned in the review, such as resolution or user-friendly design. Participants who read reviews in the convenience condition could have inferred that features not mentioned in the review were also highly satisfactory, while those who read reviews in the control condition might have assumed that the overall features of the printer were common or plain. In Study 2, we addressed these issues by manipulating stimuli such that the product in the convenience condition was more convenient than the one in the control condition while holding perceived quality constant across conditions. We created two different product descriptions directly stating product specifications. Further, while we used a utilitarian product in Study 1, we selected a product with both hedonic and utilitarian aspects as the stimulus for Study 2 to demonstrate that the primary effect observed in Study 1 is generalizable across product types.

5 STUDY 2

This study replicated the effects of convenience for a product belonging to a different category. We chose a tent as the stimulus, which has both hedonic and utilitarian features, and created fictitious product descriptions. Tents are widely used camping products often valued for utilitarian aspects such as durability or functionality. However, as tents also can be integral to enjoyable camping experiences, they have hedonic aspects, as well. To negate potential effects on perceived premiumness, we created the descriptions for each condition such that products were equivalent in terms of perceived quality. We did this by emphasizing either the product's convenience or its durability across the two experimental conditions. Our rationale was that product quality can be driven by multiple attributes, such as higher convenience or higher durability, but the perceived premiumness of the product will be driven primarily by convenience rather than durability. Thus, we attempted to ensure equivalent perceived quality across the two conditions while varying convenience. Finally, Study 2 investigated whether people perceive convenient products as more premium if they find them more customer-oriented, as predicted by H2.

5.1 Methods

Two hundred and fifteen individuals voluntarily participated in the experiment via Amazon Mechanical Turk. After the attention check, the final sample consisted of 207 participants (41.1% female, MAge = 41.10). We randomly assigned participants to either a convenience or control condition in a one-factor between-subjects design. We described four features of the tent, where one of them differed and the other three remained consistent across conditions. Participants assigned to the convenience condition read descriptions of a convenient tent (e.g., “Quick and automatic opening in 1 second”) and those assigned to the control condition read descriptions emphasizing the tent's durability (e.g., “Perfectly waterproof with double-coated high-thickness fabric”). Except for these, the other three attributes remained identical (Appendix A).

After reading the description, participants answered three items measuring perceptions of the tent's premiumness and five items assessing perceived customer orientation adapted from the Selling Orientation-Customer Orientation (SOCO) scale (Saxe & Weitz, 1982). Then, we employed the two manipulation checks used in Study 1 to assess the tent's convenience. We also measured perceived quality and perceived durability with two items each (Appendix B). We created composites for all variables.

5.2 Results

Participants in the convenience condition perceived the tent as more convenient than did those in the control condition (Mconvenience = 6.26 vs. Mcontrol = 5.67; F(1, 206) = 18.07, p < 0.001), while perceptions of the tent's durability were significantly more favorable in the control condition than in the convenience condition (Mconvenience = 4.96 vs. Mcontrol = 5.48; F(1, 206) = 7.19, p = 0.008). Additionally, the perceived quality of the tent did not differ significantly across conditions (Mconvenience = 5.79 vs. Mcontrol = 5.52; F(1, 206) = 2.95, p = 0.09). Thus, we successfully manipulated the stimuli as intended, emphasizing convenience or durability to equalize the overall perceived quality of the product. Supporting H1, participants perceived the convenient tent as more premium than the less convenient tent (Mconvenience = 5.59 vs. Mcontrol = 5.07; F(1, 206) = 9.52, p = 0.002). To test H2, predicting the mediation of perceived customer orientation, we performed Hayes's bootstrapping process (N = 5000) using Model 4 in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017). The analysis revealed a significant mediating effect of perceived customer orientation. Specifically, perceptions of customer orientation were significantly stronger in the convenience condition than in the control condition (b = 0.35, p = 0.02), and they were significantly associated with perceptions of premiumness (b = 0.64, p < 0.001). Further, the effect of convenience on perceived premiumness (b = 0.52, p = 0.002) declined when adding customer orientation to the regression model (b = 0.30, p = 0.04), showing partial mediation.

5.3 Discussion

Study 2 replicated the findings of Study 1 with a different product and different experimental manipulation. Perceived customer orientation mediated the relationship between convenience and perceptions of premiumness. From this we can infer that customers tend to confer premium status upon convenient products because they feel that such products are designed to satisfy their needs. When customers feel as though the manufacturing company is more customer-oriented, they are more likely to perceive their products as premium. Although Study 2's findings supported Hypotheses 1 and 2, even after controlling for overall product quality and durability, there still might be alternative explanations for the observed results. Stronger perceptions of premiumness for convenient products could potentially be explained by attributes other than convenience, such as innovativeness. The convenient aspects of the tent (i.e., one-touch takedown and easy storage) could lead to the inference that this product utilizes innovative technologies. In fact, consumers' propensity to adopt innovative technology is partially due to the perceived convenience of the technology (e.g., Zhang et al., 2017), indicating a close association between convenience and innovativeness. Thus, it is possible that the inference of innovativeness from convenience (rather than perceived customer orientation) is primarily responsible for stronger perceptions of premiumness. Additionally, if one infers greater innovativeness from the product's convenience, then they would also perceive greater functional efficiency. In Study 3, we accounted for the possibility that perceived innovativeness and perceived efficiency are mediators explaining the impact of convenience on premiumness perceptions.

6 STUDY 3

The purpose of Study 3 was to rule out an alternative account of the relationship between convenience and premiumness by using a different product category: desks. For greater ecological validity, instead of the obviously fictitious brand name “XYZ” used in Study 1 and 2, we utilized a more realistic brand name in Study 3. Additionally, we investigated whether the mediating effect of customer orientation is stronger among individuals with stronger productivity orientation. Finally, because we propose perceived customer orientation as the key mechanism through which convenience contributes to the perceived premiumness of the product, we also expected that this would lead to positive downstream effects and thus tested for them in this study; specifically, a customer-oriented company, as inferred from greater convenience, will generate more positive word-of-mouth, produce greater trust in other company products, and help consumers leave positive impressions on others by using the company's products.

6.1 Methods

We recruited an online panel from a research firm in South Korea, and 212 individuals participated in exchange for monetary compensation. We removed responses from eight participants who failed the attention check, yielding a final sample of 204 (51% female, MAge = 35.27) participants. We randomly assigned participants to either a convenience or control condition in a one-factor between-subjects design. We created customer reviews of a desk from the fictitious brand “SMART” for each condition. Unlike the customer reviews created for Study 1 in which the same product features (i.e., connection, two-sided printing, and speed) were mentioned in both conditions, the descriptions of the desk encountered in each condition of Study 3 contained different product attributes, as the content of real customer reviews tends to vary. The customer review in the convenience condition emphasized the desk's ease of use and time-saving qualities (e.g., “It has a one-touch height adjustment function. Once I save the height that is comfortable for working while either standing or sitting, the height is automatically adjusted by the one-touch button”), whereas that in the control condition emphasized features related to the innovative materials used in manufacturing the desk (e.g., “The desk does not move back and forth, which is common in other desks and used to get on my nerves. It stands stably due to its specially processed new materials”; Appendix A).

After participants read the descriptions, they answered the same items assessing premiumness and perceived customer orientation and the same manipulation checks as used in Study 1 and 2. Additionally, we measured perceived innovativeness and perceived efficiency to determine whether they are mechanisms through which convenience affects premiumness perception (Appendix B). We created composite scores for each variable. Finally, we asked participants whether the brand name “SMART” sounded realistic to them (“I think this brand name is quite realistic”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

For productivity orientation, we adapted four items from previous studies (Keinan & Kivetz, 2011; Landy et al., 1991; Macan, 1994; Appendix B) that assess individuals' perceptions of the importance of time management, considering that individuals with a greater productivity orientation tend to prioritize the efficient use of time. We averaged the ratings of the four items to create a composite score.

Then, participants completed three downstream behavioral and attitudinal measures of positive word-of-mouth intentions, company trust, and positive impression, respectively, (1) their willingness to recommend this product to a friend, (2) their willingness to purchase a different new product from the same company (several studies have established that trust in a company is a key driver of consumers' willingness to adopt new products [Aaker & Keller, 1990; Reast, 2005]), and (3) the extent to which they view people who use this product positively. Specifically, participants rated (1) the extent to which they would be willing to recommend the “SMART” brand desk to their friend (i.e., WTR) who is looking to buy a desk, (2) their likelihood of choosing furniture from the “SMART” brand over some other popular brand (i.e., WTB [different product]), and (3) the extent to which they would view one of their colleagues positively upon recognizing that the colleague is using a “SMART” brand desk (i.e., impression) on a 7-point scale (1 = very unlikely/very negatively, 7 = very likely/very positively).

6.2 Results

6.2.1 Manipulation check

Participants evaluated the desk in the convenience condition not only as significantly more convenient (Mconvenience = 5.20 vs. Mcontrol = 4.76; F(1, 203) = 5.91, p = 0.016) but also as more innovative than the one in control condition (Mconvenience = 5.09 vs. Mcontrol = 4.43; F(1, 203) = 13.31, p < 0.001). Efficiency ratings did not differ significantly across conditions (Mconvenience = 5.00 vs. Mcontrol = 5.04; F(1, 203) = 0.04, p = 0.85). Finally, the mean of participants' perceived realism of the brand name was 4.60, which was significantly greater than the midpoint of the scale (t(203) = 5.93, p < 0.001), indicating that the brand name “SMART” sounded realistic.

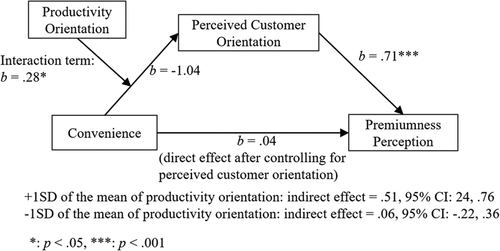

6.2.2 Effect of convenience and mediating effect of perceived customer orientation

As predicted by H1, participants perceived the desk in the convenience condition as significantly more premium than the one in the control condition (Mconvenience = 5.04 vs. Mcontrol = 4.65; F(1, 203) = 6.10, p = 0.014). This main effect persisted even after controlling for the perceptions of the brand name's realism (F(1, 203) = 5.73, p = 0.018). Hayes' (2017) bootstrapping process (N = 5000) using the PROCESS macro (Model 4) revealed perceived customer orientation's significant mediating effect (Effect = 0.35; 95% confidence interval [95% CI] from 0.13 to 0.58), supporting H2. We found that perceived customer orientation was significantly greater in the convenience condition than in the control condition (b = 0.50, p = 0.002), and it was significantly associated with premiumness perceptions (b = 0.71, p < 0.001). After controlling for perceived customer orientation, the effect of convenience on premiumness disappeared (b = 0.04, p = 0.72; before controlling for perceived customer orientation: b = 0.39, p = 0.014), showing complete mediation. We also conducted a parallel mediation test with customer orientation, innovativeness, and efficiency as mediators using Hayes' (2017) bootstrapping process (N = 5000; Model 4) to determine whether innovativeness and efficiency could be the mechanism through which convenience affects premiumness. Among these three paths, only the path through customer orientation (Effect = 0.26; 95% CI from 0.09 to 0.45) was significant, while those through innovativeness (Effect = 0.06; 95% CI from −0.06 to 0.22) and efficiency (Effect = −0.00; 95% CI from −0.07 to 0.05) were not.

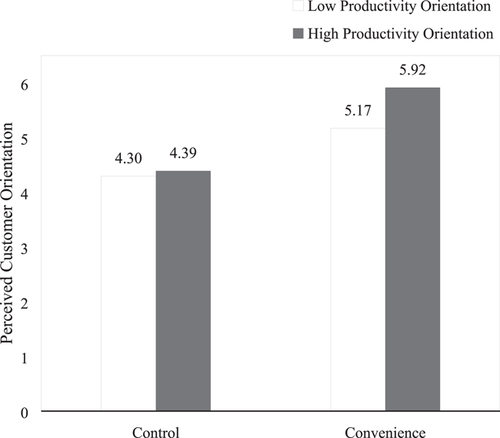

6.2.3 Moderation by productivity orientation

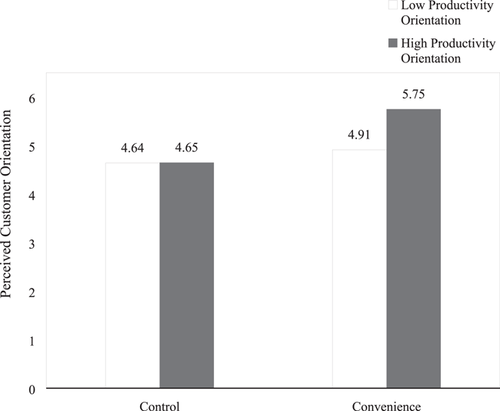

Hayes' (2017) bootstrapping process (N = 5000; Model 7) revealed productivity orientation's significant moderated mediating effect (Effect = 0.20, 95% CI from 0.02 to 0.36). The mediation path through perceived customer orientation was significant when the level of productivity orientation was high (+1 SD of the mean: indirect effect = 0.51; 95% CI from 0.24 to 0.76) but not when it was low (−1 SD of the mean: indirect effect = 0.06; 95% CI from −0.22 to 0.36). The interaction effect between convenience and productivity orientation (b = 0.28, p = 0.018) was also significant. The impact of convenience on perceived customer orientation was significant when the level of productivity orientation was high (+1 SD of the mean: Effect = 0.72; 95% CI from 0.36 to 1.08) but not when it was low (−1 SD of the mean: Effect = 0.09; 95% CI from −0.30 to 0.47).

Then, we identified regions of significance for the impact of convenience on perceived customer orientation across different levels of productivity orientation using the Johnson–Neyman procedure (Spiller et al., 2013). The effect of convenience on perceived customer orientation was significant at and above a score of 4.72 on the productivity orientation measure (at 4.72 on the 7-point scale: Effect = 0.29, p = 0.05). At scores below 4.72, there was no difference in perceived customer orientation based on convenience. Therefore, convenience led to stronger inference of the brand's customer orientation when respondents' productivity orientation was high (Figures 2 and 3).

6.2.4 Downstream effects

As H3 predicted, WTR (Mconvenience = 4.94, vs. Mcontrol = 4.35; F(1, 203) = 10.14, p = 0.002) and WTB (different product; Mconvenience = 4.79 vs. Mcontrol = 4.45; F(1, 203) = 3.17, p = 0.076) were significantly and marginally significantly greater in the convenience condition than in the control condition, respectively. Additionally, participants in the convenience condition reported that they would view colleagues who used the “SMART” brand desk significantly more positively than those in control condition (Mconvenience = 4.94 vs. Mcontrol = 4.60; F(1, 203) = 3.95, p = 0.048). The significant correlations between perceived customer orientation and all three downstream measures—WTR (r = 0.74, p < 0.01), WTB (different product) (r = 0.74, p < 0.01), and impression (r = 0.66, p < 0.01)—support the claim that convenient products have positive spillover effects on consumers' intentions and attitudes via their perceptions of customer orientation.

6.3 Discussion

Study 3 replicated the main effect of convenience and the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation in a more realistic setting, with a realistic brand name and customer reviews characteristic of real-world situations. We also ruled out the alternative explanation that innovativeness and efficiency would mediate the relationship between convenience and premiumness. Although participants perceived the desk in the convenience condition as not only more convenient but also more innovative, perceptions of innovativeness and efficiency (compared to perception of customer orientation) did not significantly mediate the relationship between convenience and premiumness. This result suggests that customer orientation is the overarching mechanism explaining many aspects of a product's perceived convenience. Additionally, we showed that the impact of convenience on premiumness through perceived customer orientation is significant only for those with strong productivity orientation, suggesting that convenience would be strongly valued by individuals who prioritize efficient time management. Finally, convenience had positive spillover effects on word-of-mouth, brand trust, and products' status-boosting capability.

While creating the stimuli for Study 3, we attempted to equalize the innovative aspects of the desk across conditions by emphasizing its innovativeness in either function or manufacturing. However, participants perceived the desk in the convenience condition as more innovative than the one in the control condition. Perhaps attributes mentioned in the convenience condition's consumer review (e.g., one-touch height adjustment function) appeared more relevant to the desk in general compared to those mentioned in the control condition (e.g., stability due to specially processed materials). Thus, participants in the convenience condition might have evaluated the desk more positively both in terms of convenience and other aspects such as innovativeness.

To address these issues, the stimuli in each condition of Study 4 contained identical product attributes. We also measured overall preference for the product, as various attributes such as safety and reliability account for it. If overall preference is similar while convenience differs across conditions, it would indicate that confounding factors other than innovativeness are also constant and would help rule out alternative explanations.

7 STUDY 4

In Study 4, we attempted to replicate the findings of previous three studies with a different product category: washing machines. We utilized washing machines as stimuli to minimize the impact of potential confounding factors such as innovativeness. We used a star rating format to manipulate the stimulus, appearing as a combination of consumer reviews and direct descriptions of product attributes, which we used in previous three studies. To exclude the confounding from the brand name, we again used the brand name “XYZ.”

7.1 Methods

Two hundred and eighty individuals voluntarily participated in the experiment via Amazon Mechanical Turk. We dropped the participants who did not pass the attention check generating 274 participants (40.1% female, MAge = 39.41). We randomly assigned participants to either a convenience or control condition in a one-factor between-subjects design. We created star ratings addressing five different attributes of a washing machine from the fictitious brand XYZ: (1) “intuitive/easy operation,” (2) “fast washing & drying,” (3) “cleaning performance,” (4) “energy saving,” (5) and “warranty.” We used a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with the attribute or feature.

We held ratings of the most critical attribute, “cleaning performance,” constant (5 stars) across conditions. In the convenience condition, we held ratings of both “intuitive/easy operation” and “fast washing & drying” constant at 5 stars, while ratings for “energy saving” and “warranty” were 3 and 2.5 stars, respectively. In contrast, attribute ratings of the washing machine in the control condition were opposite of those in the convenience condition: Both “energy saving” and “warranty” received 5 stars, while “intuitive/easy operation” and “fast washing & drying” received 2.5 and 3 stars, respectively. Cross-attribute sums of ratings were similar across conditions (Appendix A).

After participants reviewed the star ratings of the five different product attributes, they completed several measures identical to those of the previous studies, including premiumness perceptions, perceived customer orientation, perceived innovativeness, productivity orientation, and a manipulation check. Further, participants completed two items measuring overall preference for the product (Appendix B). We created composite scores for each variable and manipulation check.

7.2 Results

7.2.1 Manipulation check

Analysis of the manipulation check revealed that participants in the convenience condition perceived the washing machine as more convenient than did those in the control condition (Mconvenience = 5.91 vs. Mcontrol = 3.89; F(1, 273) = 154.69, p < 0.001). Overall preference did not differ significantly across conditions (Mconvenience = 4.79 vs. Mcontrol = 4.52; F(1, 273) = 2.56, p = 0.111). The differences in perceived innovativeness (Mconvenience = 4.91 vs. Mcontrol = 4.61; F(1, 2733) = 2.85, p = 0.092) between the convenience and control conditions were also nonsignificant. Overall, we manipulated the stimulus as intended while holding confounding factors constant.

7.2.2 Effect of convenience and mediating effect of perceived customer orientation

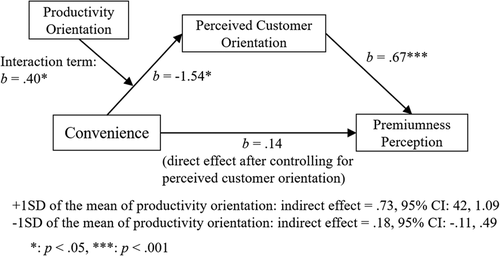

Supporting H1, participants perceived the convenient washing machine as more premium than the control one (Mconvenience = 5.09 vs. Mcontrol = 4.49; F(1, 273) = 15.02, p < 0.001). We performed Hayes's bootstrapping process (N = 5000) using the PROCESS macro (Model 4) to test the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation (Hayes, 2017). As predicted by H2, we found a significant effect (Effect = 0.46; 95% CI from 0.26 to 0.68) for the mediation path through perceived customer orientation. Specifically, perceived customer orientation was significantly greater in the convenience condition than in the control condition (b = 0.69, p < 0.001), and it was significantly associated with perceived premiumness (b = 0.67, p < 0.001). Additionally, the effect of perceived convenience on premiumness disappeared (b = 0.14, p = 0.278; before controlling for perceived customer orientation: b = 0.60, p < 0.001) upon adding customer orientation to the regression model, showing complete mediation.

7.2.3 Moderation by productivity orientation

Then, we performed Hayes's bootstrapping process (N = 5000) using Model 7 in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017) to test H4 that predicts the moderated mediation effect by productivity orientation. The analysis revealed a significant moderated mediation effect of productivity orientation (Effect = 0.27; 95% CI from 0.45 to 0.51). The mediating effect of perceived customer orientation was significant when the level of productivity orientation was high but not significant when it was low (−1 SD of the mean: Effect = 0.18; 95% CI from −0.01 to 0.48; +1 SD of the mean: Effect = 0.72; 95% CI from 0.42 to 1.06). Moreover, we observed a significant interaction effect between convenience and productivity orientation (b = 0.40, p = 0.003). The impact of convenience on customer orientation was significant when the level of productivity orientation was high (+1 SD of the mean: Effect = 1.09; 95% CI from 0.71 to 1.45) but not significant when it was low (−1 SD of the mean: Effect = 0.28; 95% CI from −0.10 to 0.65).

Next, we applied the Johnson–Neyman procedure to identify regions of significance for the effect of convenience across different levels of productivity orientation (Spiller et al., 2013). The impact of convenience on perceived customer orientation was significant at and above a score of 4.68 on the productivity orientation measure (at 4.68 on the 7-point scale: Effect = 0.35, p = 0.05). Below the level of 4.68 on productivity orientation measure, there was no difference in perceived customer orientation based on convenience. Therefore, convenience led to stronger inference of the brand's customer orientation when respondents' productivity orientation was high (Figures 4 and 5).

7.2.4 Downstream effects

Finally, downstream behavioral intentions and attitudes were more positively influenced in the convenience condition than in the control condition. Specifically, WTR (Mconvenience = 4.55, vs. Mcontrol = 4.06; F(1, 273) = 10.43, p = 0.001) and WTB (different product; Mconvenience = 4.41 vs. Mcontrol = 4.15; F(1, 273) = 3.81, p = 0.05) were significantly greater in the convenience condition than in the control condition. Additionally, participants in the convenience condition inferred significantly higher social status of people who use the XYZ brand washing machine than those in the control condition (Mconvenience = 4.82 vs. Mcontrol = 4.27; F(1, 273) = 4.12, p = 0.04). Finally, perceived customer orientation was significantly correlated with all three downstream measures—WTR (r = 0.63, p < 0.01), WTB (different product) (r = 0.61, p < 0.01), and impression (r = 0.57, p < 0.01)—supporting the idea that convenient products have positive spillover effects on consumers' behavior and attitudes through perceptions of customer orientation.

7.3 Discussion

Study 4 replicated the results of our previous studies with a different product and consumer review format. Specifically, a product's convenience affects perceptions of premiumness, and perceived customer orientation explains this relationship. As overall preference was similar across conditions, we can infer that convenience contributes to premiumness above and beyond the effects of any other important product attributes, including innovativeness. Moreover, the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation was stronger for consumers with greater productivity orientation. This implies that individuals with stronger dispositions to use time efficiently are more attracted to convenient products. Additionally, the significant interaction effect between convenience and productivity orientation on perceived customer orientation suggests that individuals with high productivity orientation will perceive the extensive efforts put into creating a product that meets customers' needs as especially beneficial. Finally, this study also confirms that product convenience's effects on consumers are not just confined to the perceptual realm but also have relevant downstream behavioral and attitudinal effects. Convenient products create positive word-of-mouth intentions, enhance consumer trust, and increase the products' own status-boosting capability because consumers infer higher customer orientation from convenient products.

8 GENERAL DISCUSSION

In this paper, we establish that convenience is a strong antecedent of products' premium status. This result suggests that marketers must highlight the convenience of a product to position it as a premium brand. Our pretest and four experiments demonstrate that products perceived as convenient are also perceived as more premium than those perceived as less convenient, even when their overall quality is held constant. This key finding was consistent across different products and experimental formats. Study 1 examined the effects of the perceived convenience of a printer using fictitious consumer reviews and showed that convenience contributes to perceptions of premiumness. Study 2 confirmed the same result for tents while perceived quality remained consistent across conditions and showed that individuals perceived convenient products as premium because they believed that the manufacturing companies were highly customer-oriented. In Study 3's replication of Study 1 and 2's results, we ruled out the alternative account by which innovativeness and efficiency are the mechanisms through which convenience affects premiumness perceptions. We confirmed that perceived customer orientation explains this relationship better than other variables and showed that the mediating effect of perceived customer orientation is significant only with strong productivity orientation. Further, we showed that convenience has positive spillover effects. Finally, in Study 4, we held overall preference for the product constant to control for potential confounding factors, replicating Study 3's results.

8.1 Theoretical and practical implications

Our findings contribute to theory in three distinct ways. First, we proposed that perceived convenience is an important factor for inferring products' premium status in the market. To our knowledge, no previous studies on status signaling have investigated the role of perceived convenience in the status inference of products. Existing literature (e.g., Han et al., 2010; Rucker & Galinsky, 2008) suggests that consumers spend money on luxury products to signal their status to others. In other words, individuals perceive high-priced luxury goods as premium. The current study showed that, in addition to well-known brand names or high prices, perceived convenience can also be instrumental in signaling a product's premium status. While convenience has been discussed primarily in the contexts of the service sector (e.g., Roy et al., 2018), shopping experiences (e.g., Reimers & Chao, 2014), and technological products (e.g., Zhang et al., 2017), it has received limited attention with respect to tangible products. Using various products, both hedonic and utilitarian, as experimental stimuli, we gathered converging evidence for our primary hypothesis that the perceived convenience of a product positively contributes to perceptions of its premium status. While existing literature on status signaling has focused on revealing an individual's status or inferring others' status, this study examined status signaling from a product evaluation standpoint. More specifically, we investigated whether convenience contributes to the perceived premium status of a product in the market, thus extending existing status-signaling research.

Second, we confirmed that perceived customer orientation is an underlying mechanism through which convenience affects perceptions of premium status. Researchers typically view customer orientation as a factor increasing organizational performance (Devece et al., 2017; Harris et al., 2014), relationship continuity with customers and their purchase intention (Park & Tran, 2018), and the value of consumers' experiences in the services or sales domains (T. J. Brown et al., 2002; Donavan et al., 2004; Rafaeli et al., 2008). Our research establishes that customer orientation can also be instrumental in influencing consumers' perceptions of a product's premium status. Today consumers are likely to pay a higher price for products that they perceive as convenient because convenient products are tailored to customers' unique needs (Franke & Piller, 2004; Franke & Schreier, 2008; Schreier, 2006). In other words, when consumers believe that a product or service has fully considered their needs, they feel well-treated and tend to perceive the product or service as premium in the market. Thus, the current study demonstrates that customer orientation can be crucial in positioning a product or service as premium.

Finally, this study's results suggest that productivity orientation may facilitate consumers' perceptions of convenient products as premium. Based on Study 3 and 4's findings, compared to individuals with weaker productivity orientation, individuals with greater productivity orientation view time- and effort-saving products as more beneficial. Study 3 and 4's results also suggest productivity orientation's important role in status signaling. Individuals with a higher productivity orientation tend to infer others' social status from their use of convenient products. According to existing status-signaling literature, people seek to demonstrate their status through the possession of high-end brands (i.e., products with a premium market status). In the present study, we found that products viewed as convenient were also perceived as premium. Based on this finding, we suggest that buying and using high-convenience products may confer high social status. This is especially likely for consumers who value productivity. Individuals with a high productivity orientation are likely to have busy lifestyles because they strive to achieve more in less time (Keinan & Kivetz, 2011). Thus, such individuals may attribute lower social status to others who do not value convenience. This is consistent with Bellezza et al.'s (2017) findings, who argue that it is better to use time rather than money to signal status: The busier people are, the higher their perceived social status. In an experiment, Bellezza et al. (2017) demonstrated that individuals buying groceries online on Peapod were perceived as having higher social status than those shopping at Whole Foods Market, which sells high-quality natural and organic foods. This aligns with our result that productivity-oriented consumers perceive time-saving products as having premium status.

The present study has several practical implications for marketers in terms of product positioning. Apart from high prices or brand names, marketers can emphasize the convenience of a product or service to position it as a premium brand in the market. High-end brands maintain their premium status indefinitely because they have an extensive loyal customer base owing to their ubiquitous brand name. However, customers may perceive lesser-known brands as attractive when companies highlight their convenience. Additionally, the current findings imply that productivity orientation is important in status signaling with convenient products and services. Currently, people live under immense pressure and unconsciously strive to achieve as much as possible in a short time. It is widely considered desirable to live a productivity-oriented life. Under these circumstances, a convenient product, which is easy to use and time-saving, will have great appeal to consumers, especially those with a high productivity orientation. When positioning a product in the market, it would be effective to emphasize its convenience while simultaneously targeting individuals with demanding jobs and high productivity orientation (e.g., consumers in high-paying professions, such as lawyers and accountants). Individuals who believe that “time is money” will perceive convenient products that save their time as being premium. Moreover, these consumers are likely to buy convenient products to signal their social status.

8.2 Direction for future research

While all our studies provide evidence that product convenience leads to premiumness perceptions, this relationship may have certain boundary conditions, especially within the service context. A fast-food restaurant may be perceived as more convenient than a fine dining establishment, but probably not as more premium. Therefore, future research should clearly identify the boundary conditions and other possible moderators of the convenience–premiumness relationship. For instance, in situations where convenience takes away from the opportunity to cocreate a product, we suspect that convenience will not signal premiumness. The popular historical example of Betty Crocker making their instant cakes “less convenient” to make them more appealing is one such example (Norton et al., 2012). Recent findings from van Esch et al. (2021) also hint at the possibility of self-efficacy as a moderator for our effect. These authors find that consumers prefer more convenient AI-enables checkouts over less-convenient self-service ones, but only under high efficacy.

The current findings could also be viewed as somewhat counterintuitive in that we linked convenience, a functional and utilitarian attribute, to premiumness, which usually has symbolic or hedonic value. Our main finding suggests that utilitarian attributes convey symbolic value to consumers. However, our findings are confined to convenience alone and do not necessarily apply to all utilitarian attributes. Moreover, we showed that highly productivity-oriented individuals inferred greater customer orientation from a convenient product than less productivity-orientated individuals, suggesting that consumers who value efficient time management appreciate convenience and thus perceive such products as premium. Thus, linking convenience to premiumness may not actually be counterintuitive, as their relationship via customer orientation is stronger for highly productivity-oriented consumers, which is a utilitarian motivation (Van der Heijden, 2004). This finding is consistent with consumers' feeling time-starved (Keinan & Kivetz, 2011) and preferring products with time-saving aspects. In contrast, it could also be possible that consumers with hedonic motivation such as need-for-status would value convenience because they view buying time-saving products as a viable status-signaling strategy (Bellezza et al., 2017), and some consider “reverse snobbery” or minimalistic consumption as a symbol of high status (Bellezza & Berger, 2020; Frank, 2013). As discussed earlier, consumers are becoming increasingly fond of unorthodox status-signaling strategies. Thus, while individuals with utilitarian motivation prefer convenient products because of their practical time-saving benefits, those with hedonic motivation may also prefer convenient products to enhance their social image. Thus, future research could examine whether the convenience–premiumness relationship is stronger for those with greater hedonic motivation such as need-for-status.

9 CONCLUSION

This study's results suggest that highlighting a product or service's convenience can influence consumers' perceptions of its premium status. Convenient products and services, which save consumers' time and effort, are especially attractive to consumers who value time. Furthermore, consumers today may use these products to indicate their high social status. Thus, across four studies we have gathered strong evidence of the positive immediate and downstream effects of product convenience. These results lend further support to the quote by Twitter cofounder Evan Williams that “convenience decides everything.”

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

APPENDIX A: STIMULI

Study 1: Printer

The following is a consumer review about a hypothetical product, “XYZ printer.” Please read it carefully and answer the following questions.

Convenience condition

I purchased this printer while searching for a laser printer for my office. It can be connected with the Wi-Fi network; hence, it is not necessary to connect my laptop with the cable. It includes auto two-sided printing, and the speed is very fast. Numerous papers can be printed at a time.

Control condition

I purchased this printer while searching for a laser printer for my office. It can be connected to my laptop with the cable. It includes manual two-sided printing, and the speed is satisfactory. A reasonable number of papers can be printed at a time.

Study 2: Tent

The following is detailed information about a hypothetical product, “XYZ tent,” on an e-commerce site. Please read the information carefully and answer the following questions.

Convenience condition

-

Quick and automatic opening in 1 s: no need for strenuous steps to build, just open the product to complete the building immediately.

-

Chic and modern style

-

Complete UV blocking that provides a cooling shade

-

An open-and-close ventilation window that allows pleasant breeze inside

Control condition

-

Perfect waterproof with double-coated high-thickness fabric

-

Chic and modern style

-

Complete UV blocking that creates a cool shade

-

Open-and-close ventilation window that allows pleasant breeze inside

Study 3: Desk

The following is a consumer review about a desk from the brand “SMART.” Please read it carefully and answer the following questions.

Convenience condition

I bought this desk after searching for one to use at the office. First, it has a one-touch height adjustment function. Once I save the height that is comfortable for working while either standing or sitting, the height is automatically adjusted by the one-touch button. Also, I have no more neck and back pain because of its angle-adjustable ergonomic monitor stand, keeping me at eye level. With a spacious desktop space and extra shelves, this desk provides plenty of room for monitors, a laptop, a keyboard, accessories, and more. Lastly, the desk has a modern design, adding to the office's interior décor.

Control condition

I bought this desk after searching for one to use at the office. First, nano-coating technology is integrated into the desk surface, making it smooth and reducing light reflection. Also, I have no more stress about the desk being unstable. The desk does not move back and forth, which is common in other desks and used to get on my nerves. It stands stably due to its specially processed new material. Water-based hardwood shows off the desk's natural beauty, and I really like it. Lastly, the desk has a modern design, adding to the office's interior décor.

Study 4: Washing machine

The following is customer ratings of hypothetical product, “XYZ washing machine.” Based on the ratings of each of the product features, please answer the following questions. Please take 30 s to read the product's rating information on the next page.

APPENDIX B

See Table B1

| Variable | Item | Reliability (Cronbach's α) |

|---|---|---|

| Premiumness perception (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) |

|

Study 1: α = 0.89 Study 2: α = 0.91 Study 3: α = 0.90 Study 4: α = 0.90 |

| Perceived customer orientation (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) |

|

Study 2: α = 0.90 Study 3: α = 0.93 Study 4: α = 0.93 |

| Productivity orientation (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) |

|

Study 3: α = 0.85 Study 4: α = 0.72 |

| Perceived durability (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) |

|

Study 2: α = 0.89 |

| Perceived quality (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) |

|

Study 2: α = 0.87 |

| Perceived innovativeness (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) |

|

Study 3: α = 0.91 Study 4: α = 0.91 |

| Perceived efficiency (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) |

|

Study 3: α = 0.89 |

| Overall preference (1 = very unattractive/very unlikely, 7 = very attractive/very likely) |

|

Study 4: α = 0.91 |

| Perceived convenience (Manipulation check; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) |

|

Study 1: α = 0.89 Study 2: α = 0.91 Study 3: α = 0.94 Study 4: α = 0.94 |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.