The Exploration of the Holistic and Complex Impacts of Creative Dance on Creative Potential Enhancement

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ABSTRACT

Interest in nurturing individuals' creative potential is rising. Yet, the potential benefits of incorporating creative embodied activities have been neglected in both applied and research settings. To address this gap, this study examined the effects of a Creative Dance program on university students' creative self-efficacy, emotional creativity, tolerance to ambiguity, and ideation behaviors. A total of 143 undergraduate students participated, either in the Creative Dance intervention or a sport-based control group for 15 weeks. A mixed-method approach using questionnaires and focus groups was adopted. Linear mixed effects models showed that engaging in Creative Dance had a significant effect on ideational behaviors and tolerance to ambiguity. Specifically, students in the intervention condition improved their ideational behaviors and remained stable in their tolerance to ambiguity compared to student in the control condition who remained stable and regressed on those variables respectively. Focus group results highlighted the social effects of the intervention, which help to contextualize the quantitative findings. This study underscores the importance of integrating creative embodied activities to foster individuals' creative potential while highlighting the need to develop comprehensive assessment tools to capture the dynamic interplay between individuals and their environment throughout this process.

The role of creativity in society is pivotal, as it serves as a cornerstone for adapting to evolving circumstances, driving innovation, and enhancing overall well-being (Acar, Tadik, Myers, Sman, & Uysal, 2021; Barbot, Besançon, & Lubart, 2015; Glăveanu, 2018; Hennessey & Amabile, 2010; Malinin, 2019). Consequently, there is a growing emphasis on cultivating individuals' creative potential through structured training programs (Valgeirsdottir & Onarheim, 2017). However, transforming one's creative potential into tangible creative endeavors necessitates the cultivation of cognitive, affective, and physical/technical skills, which are in constant interaction with the contextual constraints imposed by cultural, social, and material factors (Richard, Holder, & Cairney, 2021). As a result, designing effective creativity training programs presents a formidable challenge.

In fact, despite our understanding of individual's creative potential as a complex and multifaceted phenomenon (Barbot et al., 2015; Corazza & Glăveanu, 2020), most evidence-based training programs have focused on a unidimensional approach targeting mainly cognitive skills (Gu et al., 2022, p. 2751; Scott, Leritz, & Mumford, 2004) such as divergent thinking – the capacity to generate fluent, flexible, and original ideas or solutions (Guilford, 1967). This overreliance on cognitive skills to conceptualize, train, and assess creativity has been critiqued (Barbot, 2019; Fletcher & Benveniste, 2022) in parts because it fails to embrace the complex mind–body-environment interplay (Malinin, 2019; Torrents, Balagué, Hristovski, Almarcha, & Kelso, 2021).

According to radical embodied cognitive science (RECS), creativity is embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended (see Malinin (2019) for more details). This implies that to nurture individuals' creative potential, training programs must consider both the characteristics of a person's body (mind included) and the interaction of these characteristics with a specific environment (Marmeleira & Duarte Santos, 2019). Given that “perception, cognition, emotion, human relations, and behaviour are grounded in our bodies” (Marmeleira & Duarte Santos, 2019, p. 410), our physicality can be a relevant place of creative growth (Griffith, 2021). Hence, using creative embodied activities to address the complex holistic interplays involved in creative potential development is an underexplored, yet promising, avenue (Torrents, Balagué, Ric, & Hristovski, 2020; Valgeirsdottir & Onarheim, 2017). Specifically, the current study focuses on Creative Dance; a creative embodied activity commonly used in Physical Education, as well as in dance classes for beginners or for practitioners with wellness purposes. It combines creative movement, mime dance, physical theater, improvisation, and body expression.

CREATIVE EMBODIED ACTIVITIES

Embodied approaches to creative training generally refers to a gathering of action-oriented activities aiming at helping people become more creative (Byrge & Tang, 2015). Those action-oriented activities can range from fine-motor skills to gross and complex movement. A review exploring the effect of embodied activities on creativity identified 20 experimental studies using tasks such as objects manipulation, gestures, body postures, metaphoric movements, roaming, walking patterns, dance video games, etc. (Frith, Miller, & Loprinzi, 2020). While autonomous, random, unconstrained, and fluid motions yielded some creativity benefits, the authors concluded that more research is needed to discern the optimal embodied modalities required to foster various creativity dimensions. Interestingly, none of the studies reviewed used creative movements as a modality to ignite creative improvements. Considering that embodied creativity refers to the “creative expressions and processes that emphasize or are generated by the physical body” (Griffith, 2021, p. 1), examining the effects of activities that allow the expression of creativity through the entire body is of key interest.

In physical disciplines such as sport and the performing arts, movement creativity supports the resolution of pre-established problems or the expression of ideas or emotions by the means of the human body (Bournelli, Makri, & Mylonas, 2009; Torrents et al., 2020; Wyrick, 1968). In that context, creative embodied activities are thus designed to expand a person's possibilities to achieve movement task goals in rich and varied ways through interactions constrained by the body, the task, and the environment (Rudd, Pesce, Strafford, & Davids, 2020; Torrents et al., 2020). Specifically, training methods such as constraint-led approach (Hristovski, Davids, Araujo, & Passos, 2011; Orth, Van Der Kamp, & Button, 2019), non-linear pedagogy (Chow et al., 2006; Chow, Davids, Hristovski, Araujo, & Passos, 2011), and improvisation (Kimmel, Hristova, & Kussmaul, 2018) have been shown to lead to the emergence of creative movements in athletes (Canton et al., 2020; Coutinho et al., 2018; Orth, Davids, & Seifert, 2018; Torrents et al., 2016), dancers (Kimmel & van Alphen, 2022; Torrents, Ric, & Hristovski, 2015), and circus artists (Richard, Glăveanu, & Aubertin, 2022). While this line of research advances knowledge on the effectiveness of creative embodied activities' modalities (e.g., the use of constraints, variability, noise, etc.), its main focus on motor performance outcomes fails to capture the holistic impacts of such activities.

Acknowledging the intricate interplay between the brain and the body (Gallagher, 2015) it becomes evident that engaging in whole-body movement offers avenues for novel perceptions, altered perspectives, and the externalization of ideas (Frith et al., 2020). Consequently, creative movement has the potential to induce cognitive, affective, and social transformations in individuals. The subsequent section delves into exploring this comprehensive notion.

THE HOLISTIC IMPACTS OF CREATIVE EMBODIED ACTIVITIES

Moving the body creatively can be intimidating initially, especially if someone has little experience or has been taught to move in a prescriptive way. In higher education, the initial emotional challenges triggered by the integration of creative embodied activities as part of degrees' curriculum can lead to student's refusal to participate (Caballer, Oliver, & Gil, 2005). Romero-Martín and Caballero-Julia (2022) suggest that fear, embarassment, expectations, and low ability perception inhibit movements increasing the likelihood of disengaging with creative movement practices.

The lack of perceived ability factor is in line with the idea that low self-efficacy plays a role in task engagement (Bandura, 1997). Specifically, creative self-efficacy refers to “a person's perceived confidence to creatively perform a given task, in a specific context, and at a particular level” (Beghetto & Karwowski, 2017, p. 5). Hence, in the context of creative embodied activities, fostering one's perceived ability to move creatively is key to promote engagement.

Interestingly, the integration of a 40-h “body and motor expressiveness” course, as part of a University degree, helped students overcome their initial insecurities resulting in greater self-confidence (Monge & Idoiaga, 2022). Similarly, following 60-hours of body expression classes focused on emotions, university students improved their perception of self. It is suggested that, once the initial emotional challenges are overcomed, engaging in creative embodied activities enhance people's perception of their creative movement ability leading to greater creative self-efficacy (Romero-Martín & Caballero-Julia, 2022).

The initial challenges afforded by creative embodied activities might also develop individuals' tolerance to ambiguity. Whether it is movement improvisation, body expression, or creative dance, these activities promote the exploration of an infinite number of ways to express individualities through the body. While this breath of possibilities might be appealing to some, the freedom to explore combined with no prescribed outcome expectation might be perceived as ambiguous for others (Monge & Idoiaga, 2022). Tolerance to ambiguity (TA) refers to the individual's ability to handle ambiguity and their level of comfort with it, whether they find it aversive or attractive (McLain, 2009). Following a movement improvisation program, elite athletes reported becoming more comfortable with doing ridiculous movement or being different (Richard, Halliwell, & Tenenbaum, 2017). The program also significantly impacted their creative attitude and values. Empirical evidence supports such positive relationship between tolerance to ambiguity and creativity (Wang, Zhang, & Martocchio, 2011; Zenasni, Besançon, & Lubart, 2008).

In addition to the emotions evoked by moving differently, creative embodied activities are also designed to encourage the deliberate expression of a wide range of emotions through the body. For instance, in Creative Dance, participants might be asked to explore ways to express sadness through various body movements or to choreograph a movement sequence that reflects different intensity levels of happiness. The high emotional content of these activities open spaces for connecting with emotions at a mind–body level which may unlock various creative dimensions (Monge & Idoiaga, 2022). Namely, emotional creativity is defined as “a person's ability (a) to connect with the reasons for and consequences of the emotional responses at the preparation stage of the creative process (i.e., emotional preparedness) and (b) to experience and express novel, effective, and authentic emotions at the verification stage of the creative process (i.e., emotional novelty and emotional effectiveness/authenticity respectively)” (Soroa, Gorostiaga, Aritzeta, & Balluerka, 2015, p. 233). Because of the strong emphasis of creative embodied activities on connecting with and expressing emotions, engaging in such activities could be a suitable way to develop emotional creativity. Surprisingly, this hypothesis has yet to be tested.

Finally, while ideation is frequently associated with cognitive processes and activities, evidence are suggesting that embodied activities can foster ideational behaviors (IB) – the tendency to generate and appreciate ideas, think in alternative ways, and solve problems effectively (Runco et al., 2014). For instance, following 21 hours of body expression sessions, male college students significantly improved their scores on a creative ideation test (Vidaci, Vega-Ramírez, & Cortell-Tormo, 2021). Similarly, compared to students reading about creativity, college students engaged in a movement improvisation program significantly improved their originality score on a figural divergent thinking task (Richard, Ben-Zaken, Siekańska, & Tenenbaum, 2021).

THE CURRENT STUDY

Given that creative potential is a latent ability combining cognitive, affective, physical/technical resources, fostering it requires a holistic approach (Barbot et al., 2015; Richard, Holder, & Cairney, 2021). The studies described above provide preliminary evidence for the holistic role of creative embodied activities on the development of some of those creative potential's resources. Nevertheless, more research is needed to support and unpack its full impact. To better capture the complex holistic interplay involved in creative potential development, the current study aims to examine the effects of a 15-week Creative Dance course on university students' creative self-efficacy, tolerance to ambiguity, emotional creativity, and ideation behaviors.

Because Creative Dance expands a person's possibilities to express ideas and emotions through the body, it is expected to impact positively emotional creativity and ideational behaviors. Moreover, given the Creative Dance course is integrated to the curriculum of a Sport Sciences undergraduate degree, participants usually have little experience with moving their body creatively. Hence, this course is expected to provide students an opportunity to challenge their tolerance to ambiguity and foster their creative self-efficacy.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 150 students enrolled in the first year of the Physical Activity and Sport Sciences Degree of the Universitat de Lleida were invited to participate in the present study. The students were split into five groups of 22–30 students through the regular university scheduling process. Four groups were assigned to the Creative Dance course (i.e., intervention condition) during their first year, while the fifth group, who were pursuing a double degree, would enroll in the course only in their third year. This fifth group served as the control condition for this study. While participation in the Creative Dance course was mandatory as part of the degree requirements, participating in the study was voluntary. To respect confidentiality and ensure that the study's results would not impact academic evaluations, a process of blinding the names of the participants was followed in all phases of the study.

A total of 143 students (48 women and 95 men) aged between 19 and 36 years old (M = 20.32 ± 2.40) agreed to participate in the study, with 22 assigned to the Control condition and 121 assigned to the Intervention condition. Most participants had little or no experience in dance or theater activities. Only 19% of students had some experience, which included rhythmic gymnastics (n = 6), artistic gymnastics (n = 1), physical theater (n = 3), synchronized swimming (n = 1), figure skating (n = 1), dance training at school (n = 8), contemporary dance (n = 2), urban (n = 2), jota (n = 1), hip hop (n = 4), traditional Basque dance (n = 1), bachata (n = 1), traditional Catalan dance (n = 1), ballet (n = 1), and aerobics (n = 1). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of the Catalan Sports Council and complied with relevant guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

DESIGN AND PROCEDURE

A mixed methodology following a concurrent triangulation strategy was used to collect data in the current study (Creswell, 2009). Such a strategy consists of collecting both quantitative and qualitative data in the same research phase. Data sources are then compared to highlight convergences, divergences, or some combinations to strengthen findings. This mixed methods strategy is advantageous because it reinforce interpretation and can result in well-validated findings (Creswell, 2009). Therefore, a quasi-experimental repeated measures design was adopted to collect quantitative data. Specifically, scales were used to examine the effects of the intervention on the selected variables. Because students were allocated to conditions based on their study profile (i.e., control conditions = double-degree students) randomizing the sample was not feasible. The qualitative data were collected using focus groups.

On the first day of the intervention, all participants were asked to fill out a demographic form and a series of scales assessing students' creative self-efficacy, tolerance to ambiguity, emotional creativity, and ideation behaviors. The same scales were administered again at a later point during the intervention (18th session) and at the end of the intervention (36th session). All scales were completed online during class time. The scales were presented in the same order at every measurement point. After the official publication of the academic marks, students were invited to participate voluntarily in one of the two focus groups to discuss the impact of the intervention. The focus group was facilitated by one of the teachers (last author) to ensure a supportive and inclusive environment.

INTERVENTION

Three Creative Dance teachers (including third and last author) designed the course which is a mandatory subject integrated into the second semester of the first year of a Sport and Physical Activity Sciences degree program. Participants engaged in 36 Creative Dance sessions, each lasting 90 min, over a period of 15 weeks. The three teachers divided the delivery of those sessions based on their specific expertise in Creative Dance.

Table 1 provides the schedule and content of the Creative Dance classes. The initial two classes focused on introducing the course content and establishing rapport with the students. The concept of movement creativity and strategies for its development were elucidated in the third session. The fourth class concentrated on overcoming inhibitions through rhythmic and amusing movement tasks, emphasizing the cultivation of group confidence. Subsequent sessions predominantly involved expressive bodily movement (EB), exploration of movement in relation to space (EME), time and rhythm (EMT), and energy or quality (EMQ). Additionally, various dance and theater techniques (including contemporary, hip hop, salsa dance, and stage combat) were explored. One session was dedicated to body alignment for dance. Nearly all sessions involved the creation of original movements, except for those designated as “theoretical,” as indicated in Table 1. For instance, students were tasked with creating their own movements, proposing new movement combinations, improvising while dancing, exploring fundamental physical theater or creative dance techniques, and presenting creative works (e.g., short dance pieces, imaginative videos incorporating hand movements or facial expressions). Each session commenced with an introductory activity aimed at enhancing concentration or fostering a conducive environment for creativity. Time for theoretical discussions or comments was allotted during or at the conclusion of each class. Each teacher brought their own individual style to the class, yet they all adhered to this process.

| Lessons | Content | Class type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Testing (baseline) + Presentation of the subject using practical and creative tasks | Movement |

| 2 | Students' presentation using oral communication + creation of a Hai Ku | Theoretical |

| 3 | Theory of creativity | Theoretical |

| 4 | Group tasks to develop group confidence and creativity | Movement |

| 5 | Gestures (improvisation tasks and creation of a video with hand movements) – EB | Movement |

| 6 | Walking task + representation of personalities by means of the walk − EB | Movement |

| 7 | Group tasks using rhythm with basket balls to develop confidence | Movement |

| 8 | Explanation of the evaluation and discussion | Theoretical |

| 9-10-11 | Body percussion (creative tasks and creation of rhythm sequences) − EMT | Movement |

| 12-13 | Preparation of a performance using body percussion (no creative involvement from students) | Movement |

| 14 | Center of mass movements (improvisation using individual and contact tasks) − EB | Movement |

| 15 | Individual posture and creation of collective figures − EB | Movement |

| 16-17 | Movement in the space (improvisation and creative tasks) − EME | Movement |

| 18 | Revision of student's group choreographies + testing (time 1) | Presentation |

| 19 | Energy and qualities of movement (improvisation and creative tasks) − EMQ | Movement |

| 20 | Evaluation of the students' group choreographies | Presentation |

| 21 | Energy and qualities of movement (improvisation and creative tasks) − EMQ | Movement |

| 22 | Body alignment in dance (no creative involvement from students) | Movement |

| 23-24 | Contemporary dance | Movement |

| 25-26 | Hip Hop dance (no creative involvement from students) | Movement |

| 27-28-29 | Stage combat and fight acting (practice of techniques and creation of sequences) | Movement |

| 30 | Production and direction | Theoretical |

| 31 | Composing in dance or salsa dance | Movement |

| 32-33-34 | Choreographies revision | Presentation |

| 35 | Students' creative oral presentations | Presentation |

| 36 | Introduction to circus arts + Testing (time 2) | Movement |

Finally, students showcased their creative works to the University community twice. After the 13th session, students collaborated on a dance performance related to sport and gender, and following the 34th session, groups of six to eight students presented their choreographies at the Artistic Night, a dedicated event for students to showcase their creative endeavors. These choreographies constituted part of the assessment and were developed outside of class time, with teacher's guidance provided during tutorial sessions, and refinement and enhancement occurring during sessions 18, 20, 32, 33, and 34. Additionally, students collaborated in groups of six to eight to prepare a creative oral presentation on the application of Creative Dance in various contexts (such as in schools, sports, artistic activities, or wellness programs), which was presented during the 35th session. The last class introduced circus techniques.

MEASURES

Creative self-efficacy in movement

Because there is no all-purpose measure of self-efficacy and the “one measure fits all” approach yields poor explanatory and predictive value, Bandura (2006) designed a guide for constructing tailored self-efficacy scales. These guidelines were followed to create a scale measuring creative self-efficacy tailored to the task demands of the movement intervention implemented in this study. First, because “perceived self-efficacy is a judgement of capability to execute given types of performances” (Bandura, 2006, p. 309), the initial instruction asked participants to “rate how confident are you that you can effectively…”. This is also in line with Beghetto and Karwowski (2017) recommendations to design measures of creative self-efficacy. Items were then constructed around the key performance features of Creative Dance (Beghetto & Karwowski, 2017). Specifically, two experts (first and last authors which also teaches the sessions) detailed the abilities targeted by Creative Dance. Totally 10 items were created around participants' abilities to move in original ways, express their thoughts and emotions through movement, use the environment to move creatively, and create sequence of movements. Participants rated the strength of their efficacy beliefs on a 100-point scale as recommended (Bandura, 2006; Beghetto & Karwowski, 2017). The scale was also inspired by prior work on creative self-efficacy (e.g., Karwowski, Gralewski, & Szumski, 2015). Internal consistency was considered excellent at all three time points (Cronbach's α = 0.949 to 0.965).

The multiple stimulus types ambiguity tolerance scale (MSTAT-II; McLain, 2009)

The MSTAT-II is a 13-item self-report scale asking participants to rate their level of agreement for each suggested stimulus (i.e., novel, complex, insoluble, and ambiguous in general) on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Spanish version has been tested for validity and reliability, revealing very high internal consistency and high temporal stability. Results confirmed that the MSTAT-II translated in Spanish is a valid measure of ambiguity tolerance (Arquero & McLain, 2010). Internal consistency was considered acceptable or good at all three time points (Cronbach's α = 0.783 to 0.827).

Shortened Spanish version of the Emotional Creativity Inventory (ECI-S; Soroa et al., 2015)

The ECI-S consist of a 17-item self-report questionnaire that provides information about emotional preparedness, novelty, and effectiveness/authenticity. Participants were asked to assess their ability to experience and express emotions on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The Spanish version showed adequate internal consistency and temporal stability and confirmed the three-factor structure of the original scale. Internal consistency for the preparedness (Cronbach's α = 0.706 to 0.759), novelty (Cronbach's α = 0.706 to 0.783), and effectiveness/authenticity (Cronbach's α = 0.719 to 0.768) subscales were considered acceptable at all three time points.

Runco Ideation Behavior Scale (RIBS; Runco, Plucker, & Lim, 2001)

RIBS consists of 23 items of which participants must indicate the frequency of occurrence of each ideational behavior on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) (Runco et al., 2014). The Spanish version confirmed the 2-factor model and showed good discrimination and satisfactory reliability (López-Fernández, Merino-Soto, Maldonado Fruto, & Orozco Garavito, 2019). The first factor includes positive statements about ideation behaviors (e.g., “I like to play around with ideas for the fun of it”) while the second factor depicts negative ones (e.g., “Sometimes I get so interested in a new idea that I forget about other things that I should be doing”). Internal consistency for the full scale was considered good to excellent at all three time points (Cronbach's α = 0.883 to 0.912), whereas internal consistency for the first factor was considered good at all three time points (Cronbach's α = 0.863 to 0.898), and the second factor was considered acceptable at all three time points (Cronbach's α = 0.747 to 0.786).

FOCUS GROUP

After the intervention, two focus groups were conducted by the main teacher. The first focus group took place on campus and included 7 volunteered students (4 men and 3 women). The second focus group was conducted online using the University's virtual campus and involved 3 volunteered students (2 women and 1 man). Each focus group interview lasted approximately 60 min. A semi-structured interview format was used to allow flexible interaction while covering the main themes of interest (Savoie-Zajc, 2009). The interview questions were open-ended and based on an interview guide that matched the study's variables (i.e., creative self-efficacy, tolerance to ambiguity, emotional creativity, and ideation behavior). Open-ended questions are considered an efficient way to capture direct quotations about personal perspectives and experiences. Additionally, using an interview guide helps standardize questions across groups and minimize bias (Patton, 2002). The interview guide can be found in the Appendix S1.

Before each focus group session, the facilitator emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers (Sparkes & Smith, 2014). Furthermore, Silverman's (1973) recommendations were followed to ensure efficient interview procedures. Each focus group started with general questions relating to the participants' experience and learning throughout the intervention. Then, questions were targeted toward their perceived changes in the four variables of interest. After each question, the interviewer summarized her comprehension of what was shared, and the participants were encouraged to correct her if her interpretation was lacking precision. At the end of the interview, the participants were asked about their appreciation of the intervention and were invited to add any comment on its perceived effects. Finally, the students were thanked for participating and reminded that all results would remain confidential.

DATA ANALYSIS

Quantitative analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all study variables. The effectiveness of the intervention on the dependent variables were evaluated using separate linear mixed effects models with main effects of Time (Baseline, Time 1, Time 2) and Condition (Control vs. Intervention) as well as a Time × Condition interaction set as fixed effects. Sex and prior years of experience with corporal expression or dance were included as covariates in all models. For each dependent variable, a series of five models were computed to identify the best fit for the data: (a) Participant set as random intercept with a linear fixed effect for Time; (b) Participant set as random intercept with a quadratic fixed effect for Time; (c) Participant set as random intercept and Time set as a random slope with a linear fixed effect for Time; (d) Participant set as random intercept, nested within group (four intervention groups and one control group), with a linear fixed effect for Time; (e) Participant set as random intercept, nested within group, and Time set as a random slope with a linear fixed effect for Time. The best model fit was determined by comparing BIC values in which lower values represent better fit. In instances when the model fits were relatively equivalent (i.e., BIC values differing by less than 2), the simpler model was selected. All analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.0) and R Studio (version 2023.03.1, Boston, MA) using the lme4 (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) and lmerTest packages (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen, 2017). Linear mixed models were employed as they provide several advantages over repeated measures analysis of variance such as taking into consideration the nested structure of observations within participants, handling missingness on the dependent variable via full information maximum likelihood (FIML), and flexibility for dealing with unequal sample sizes across conditions (Boisgontier & Cheval, 2016). Missingness on the dependent variables was handled via FIML, whereas there was no missing data for the covariates included in the models and thus no further procedures were required. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data from the focus group were analyzed using Kennedy and Thornberg's (2018) approach. Specifically, abductive analysis was employed to uncover novel insights, develop new hypotheses, identify hidden patterns in the data, and provide insightful explanations to the quantitative findings. It is therefore a relevant analysis method for expanding the theoretical understanding of the phenomena and generating new avenues for future research.

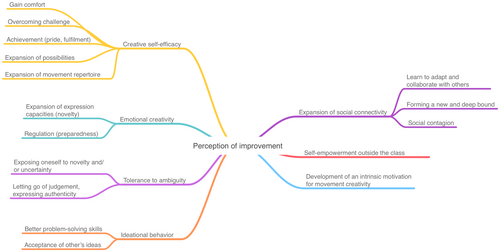

Focus groups' transcriptions were uploaded to a qualitative analysis software (Nvivo 12, QSR International, Burlington, MA, USA), and analyzed by an independent researcher following the six stages outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006, 2019). First, the researcher familiarized herself with the data by reading the transcripts. Initially, codes were generated for each studied variables (main themes) through a deductive content analysis (i.e., building on theoretical frameworks). Simultaneously, an inductive content analysis was employed to identify novel themes (Bingham & Witkowsky, 2022). Specifically, when a meaning unit could not be associated with one of the studied variables, a new code was developed in accordance with the data. All codes were then grouped into a list of candidate themes and subthemes and discussed by two researchers using a mind map.

Upon completing the map, the research team met to resolve coding discrepancies and reach a consensus. Decisions regarding the grouping were based on the study's aims and theoretical frameworks underpinning the dependent variables. Such methods are considered efficient for analyzing qualitative data in the sports domain (see Biddle, Markland, Gilbourne, Chatzisarantis, & Sparkes, 2001 for a review). To reduce bias and increase the reliability of the coding, an external researcher coded 25% of the data and the agreement rate was calculated using percent agreement. Initially, the agreement rate was 84%, but upon revision two categories were combined as they had similar meanings. This led to an improvement in the agreement rate to 89%. According to Miles and Huberman's (1994), a minimum of 70% intercoder agreement is satisfactory.

RESULTS

QUANTITATIVE RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for all variables included are reported in Table 2. A series of chi-square tests revealed no differences for gender, ethnicity or experience between the conditions (all ps > .05), whereas a Welch unpaired-samples t-test for age revealed the intervention group (M = 20.48) was roughly 1 year older than the control group (M = 19.52), t = −3.46, df = 120.56, p < .001. A series of Welch unpaired-samples t-tests also revealed non-significant differences between the conditions for each of the dependent variables at baseline (all ps > .05). Missingness on the dependent variables ranged from 1% at Baseline (Intervention: n = 2) to 2% at Time 1 (Control: n = 3; Intervention: n = 2) and 13% at Time 2 (Control: n = 3; Intervention: n = 17).

| Variables | Control Condition (n = 22) | Intervention Condition (n = 121) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Time 1 | Time 2 | Baseline | Time 1 | Time 2 | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| CSE | 62.3 | 15.5 | 65.0 | 17.7 | 71.5 | 16.4 | 57.4 | 16.8 | 60.1 | 16.6 | 69.9 | 15.6 |

| EC – prep | 4.62 | 0.881 | 4.70 | 0.909 | 4.51 | 1.08 | 4.49 | 0.747 | 4.32 | 0.770 | 4.60 | 0.743 |

| EC – novel | 3.87 | 0.473 | 3.74 | 0.743 | 3.84 | 0.666 | 3.85 | 0.758 | 3.86 | 0.712 | 4.11 | 0.746 |

| EC – eff | 4.05 | 0.757 | 3.99 | 0.914 | 4.07 | 0.875 | 4.11 | 0.776 | 4.03 | 0.733 | 4.24 | 0.745 |

| IB | 2.09 | 0.437 | 2.24 | 0.535 | 2.27 | 0.531 | 2.23 | 0.486 | 2.20 | 0.478 | 2.36 | 0.513 |

| IB – factor 1 | 2.20 | 0.470 | 2.37 | 0.608 | 2.37 | 0.578 | 2.34 | 0.485 | 2.27 | 0.472 | 2.45 | 0.511 |

| IB – factor 2 | 1.78 | 0.698 | 1.87 | 0.659 | 1.99 | 0.651 | 1.93 | 0.705 | 2.02 | 0.636 | 2.11 | 0.698 |

| TA | 3.01 | 0.653 | 2.80 | 0.570 | 2.73 | 0.485 | 3.11 | 0.429 | 3.02 | 0.413 | 3.03 | 0.494 |

- Note. CSE = creative self-efficacy; EC – prep = Emotional Creativity – preparedness; EC – novel = Emotional Creativity – novelty; EC – eff = Emotional Creativity – effectiveness and authenticity; IB = Ideational Behaviors; TA = Tolerance to ambiguity.

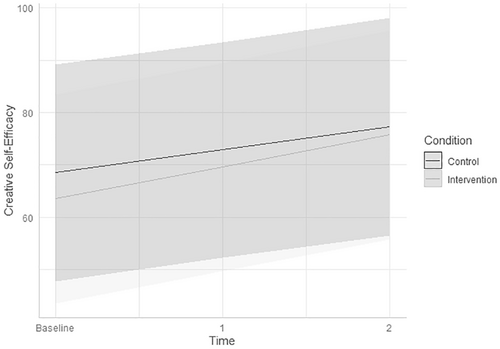

Creative self-efficacy

The model with a random intercept for Participant demonstrated the best fit. The results demonstrated a significant main effect of Time (B = 4.39 ± 1.54 SE, p = .004) in which creative self-efficacy increased over time (see Figure 1), however, the main effect of Condition (B = −4.98 ± 3.59 SE, p = .168) and Time X Condition interaction were not statistically significant (B = 1.73 ± 1.68 SE, p = .306).

Emotional creativity—Preparation

The model with a random intercept for Participant demonstrated the best fit. The results did not demonstrate statistically significant main effects of Time (B = −0.05 ± 0.08 SE, p = .553), Condition (B = −0.22 ± 0.18 SE, p = .221), or a Time X Condition interaction (B = 0.08 ± 0.09 SE, p = .374) for the ECI-Preparation subscale.

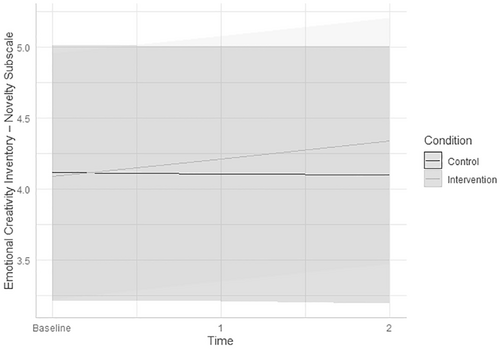

Emotional creativity—Novelty

The model with a random intercept for Participant demonstrated the best fit. While descriptive statistics showed an improvement of the intervention condition while the control condition remained stable over time (see Figure 2), results did not demonstrate statistically significant main effects of Time (B = −0.01 ± 0.07 SE, p = .926), Condition (B = −0.03 ± 0.16 SE, p = .871), or a Time × Condition interaction (B = 0.13 ± 0.07 SE, p = .074) for the ECI-Novelty subscale.

Emotional creativity—Effectiveness and authenticity

The model with a random intercept for Participant demonstrated the best fit. The results did not demonstrate statistically significant main effects of Time (B = 0.02 ± 0.07 SE, p = .822), Condition (B = 0.04 ± 0.17 SE, p = .830), or a Time × Condition interaction (B = 0.04 ± 0.08 SE, p = .598) for the ECI-Effectiveness and Authenticity subscale.

Ideational behaviors

The model with a random intercept for Participant demonstrated the best fit. The results did not demonstrate statistically significant main effects of Time (B = 0.07 ± 0.04 SE, p = .071), Condition (B = 0.10 ± 0.11 SE, p = .381), or a Time × Condition interaction (B = 0.00 ± 0.04 SE, p = .919) for the RIBS.

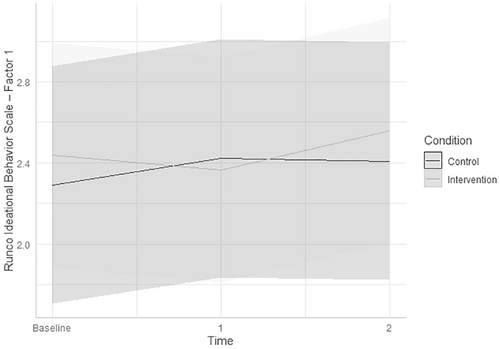

Ideational behaviors—Factor 1

The model with a random intercept for Participant and a quadratic fixed effect for time demonstrated the best fit. The results demonstrated a statistically significant Time × Condition interaction (B = 0.20 ± 0.08 SE, p = .013) for the RIBS Factor 1, in which the Intervention condition reported higher scores at Baseline and Time 2, whereas the Control condition reported higher scores at Time 1 (see Figure 3). However, the main effects of Time (B = −0.07 ± 0.08 SE, p = .347), Condition (B = 0.15 ± 0.11 SE, p = .201) were non-significant.

Ideational behaviors—Factor 2

The model with a random intercept for Participant demonstrated the best fit. The results did not demonstrate statistically significant main effects of Time (B = 0.11 ± 0.06 SE, p = .06), Condition (B = 0.13 ± 0.15 SE, p = .379), or a Time × Condition interaction (B = −0.01 ± 0.07 SE, p = .898) for the RIBS Factor 2.

Tolerance to ambiguity

The model with a random intercept for Participant demonstrated the best fit. The results demonstrated a statistically significant Time × Condition interaction (B = 0.11 ± 0.05 SE, p = .025) for Ambiguity Tolerance, in which the Intervention condition reported relatively stable higher scores at all timepoints in comparison to the Control condition which declined over time. A significant main effect of Time was also observed (B = −0.15 ± 0.04 SE, p < .001), whereas the main effect for Condition was non-significant (B = 0.10 ± 0.10 SE, p = .349).

QUALITATIVE RESULTS

The findings are reported in relation to the participants' perception of their improvement throughout the intervention. Figure 4 presents the factors associated to improvements in creative self-efficacy, emotional creativity, tolerance to ambiguity, and ideational behaviors. Because the interview process allowed participants to expand beyond these main variables, three other themes emerged namely expansion of social connectivity, self-empowerment outside the class, and development of an intrinsic motivation for movement creativity (see Table S1 for additional quotations for each emerging theme).

Participants' perception of improvement

Creative self-efficacy

Findings revealed that self-efficacy was influenced by participants' increased comfort, capacity to overcome challenges, sense of achievement, and perception of expanded movement repertoire and possibilities. For instance, P10 reported on their increased comfort throughout the class: “When you work on mental creativity every day in each class, you start feeling more comfortable coming up with ideas, proposing, and breaking away from the ordinary, from your most stable movements to losing the fear of doing things differently.” On the other hand, overcoming emotional challenges was a very important aspect during the intervention, as P6 stated, “seeing that people were in the same situation has helped me to let go much more and understand that shame is useless.” Similarly, P2 mentioned that “losing the shame, losing the discomfort with people, standing in front of everyone at the Artistic Night made me less nervous later.” Another participant (P6) shared how much their movement repertoire expanded: “Now I know that I can do movements that I didn't know I could do. For example, on the day of ‘water’ and ‘ground’, I didn't know what to do, and then the teacher started to move, and then I moved. We all have more possibilities of movement than before. I'm not sure if I'm more creative, but I'm clear about it in movement.” Finally, P4 expressed their sense of achievement as follows: “On a personal level, it is ultimately what has left me most satisfied. It has taken much effort, but the truth is that it is very fulfilling. You feel good about yourself seeing what you have created and accomplished. For me, it's the most important thing.”

Emotional creativity

Emotional creativity was impacted mainly by participants' expansion of expressive capacities and better regulation skills. P10 reported: “I realized that I have gained a lot of knowledge from the classes. It was a crucial moment for me as it allowed me to be more open, free-spirited, and creative. I also began to consider how we could uniquely enhance traditional dance” whereas P9 simply mentioned “It gives you tools to express yourself.” Regarding emotional regulation, P2 revealed that: “I experienced a sudden shift from happiness to sadness. I generally avoid displaying my emotions because I don't feel comfortable. Revealing one's emotions can make you vulnerable, and I prefer to avoid this. It's like a protective barrier. However, I believe this approach has helped me become more expressive.”

Tolerance to ambiguity

Letting go of judgment and exposing oneself to novelty and uncertainty are factors that supported participants' capacity to better tolerate ambiguity. For instance, P8 mentioned: “Not thinking so much about what others will think of what I do or the ideas I propose” and P2 “I lost the shame and stopped feeling uncomfortable about showing how I move and express myself”. Finally, some participants were able to expose themselves to novelty and uncertainty as mentioned by P1: “You had to try many little things throughout the course, taking one and trying until it worked and not stopping.”

Ideational behaviors

Through better problem-solving skills and acceptation of other's idea, ideational behaviors were optimized. P4 shared his problem-solving progress: “I'm not a creative person, but I have made a lot of effort to think and imagine new things to do, which has helped me.” P3 explains how to figure out solutions by exploring challenges: “At first, I didn't think this one thing would work in the dance routine, but then I figured out how to make it fit”. Another participant stated: “Maybe now it's easier to bring them [ideas] out or even reverse them. What seemed impossible before, becomes viable now.” Accepting others' ideas could also be a source of improvement as illustrated by P9 “I have realized that many times I need to be more flexible, I need to lighten up, I need to allow people to express their ideas and for their ideas to be imposed without me getting nervous or desperate.”

Other improvements

Beyond the variables that were examined quantitatively, other factors were perceived as contributing to participants' overall improvement.

Expansion of social connectivity

Social connectivity was expanded because, throughout the classes, participants learned how to adapt to and collaborate with others, influenced each other through social contagion, and formed new and deep bonds. Social contagion was illustrated by P9, who stated: “One person would do something, and the others would follow what he/she started doing first. We were like puppies following their mother at the beginning.” Social bounding was articulated by P4 as follows: “We formed relationships with people with whom we didn't have much connection, and after all, we bonded more with the class.” Likewise, P1 shared that “Thanks to the choreography and the hours I have spent with these seven wonderful friends I have made, I carry a piece in my heart that I don't want to lose, I want to stay in touch.”

Self-empowerment outside the class

Participants perceived that the intervention was contributing to their empowerment outside of the class. One participant (P2) revealed that “It has made me think more for myself. I have improved my creativity because I'm more independent in creating my own stories… or suddenly, I can start singing like crazy in the car or improvising. As long as no one is around, I go for it.” Another student (P9) disclosed that “It may seem silly, but once I went out with some friends, and we were dancing, and one of them said, ‘Hey, you've improved, haven't you?’ and I felt very proud because I used to feel like a robot. I've always been a ‘stick’.”

Development of an intrinsic motivation for movement creativity

The classes also ignited an intrinsic motivation for movement creativity in some participants. For instance, P6 shared: “I didn't care about the grade at all, I wanted to dance because I have a great time dancing and because I was excited about it.” Similarly, P10 revealed that: “Two weeks before the Artistic Night, you would go to the hall and it was filled with groups practicing their dance, we were all correcting things that the teacher had told us, putting in a lot of effort because, deep down, and you don't know why, you really wanted that dance turn out well.”

DISCUSSION

To investigate the holistic role of creative embodied activities on the development of individual's creative potential, this study sought to explore the effects of a Creative Dance intervention on creative self-efficacy, emotional creativity, tolerance to ambiguity, and ideational behaviors. While descriptive statistics showed improvement in all variables except tolerance to ambiguity for the intervention condition, only changes in ideational behaviors (factor 1) significantly and positively differ from the control condition. Qualitative analysis allowed the identification of various factors underlying participants perception of improvement for these variables in addition to provide new perspectives on the social impacts of the intervention.

The Creative Dance intervention had an interesting effect on participants' positive ideational behaviors (i.e., factor 1): They got worse before they got better. Different reasons could explain this effect. First, the intervention may have helped students become more conscious of what creative ideation requires and the possibilities that fostering their creative potential affords. If they were not used to creative methodologies, students may have perceived their creative behaviors as adequate when first exposed to the scale (Baas, Koch, Nijstad, & De Dreu, 2015). Yet, after facing and overcoming a few ideational challenges, as reported by the participants interviewed, they may have perceived area for improvement resulting in a lower assessment of their creative behaviors mid-way through the intervention. This explanation is in line with competence models which suggest that a state of unconscious incompetence is preceding states of consciousness (Peel & Nolan, 2015; Verklan, 2007). While these models are mainly used to guide professional trainings (e.g., Ramani, Könings, Mann, & Van Der Vleuten, 2017; Weber & Aretz, 2012), whether this apply to creative potential development is intriguing.

The individual and team processes at play in collaborative creation may provide a second explanation to support the pattern of change in student' ideational behaviors. Specifically, the Complex Systems approach is useful to explain the nonlinear processes involved when groups are facing collective creative challenges (see Torrents et al., 2021). In the current study, the choreographic work presented such challenges. At the beginning of the creative process, students individually proposed ideas that were accepted or rejected by their peers. Some movement ideas thus ‘won’ and become temporally stabilized, while others lost their stability (Hristovski et al., 2011). Depending on the team dynamics, this may have provoked disagreements, frustration, and/or disappointment. Rather than ignoring these conflictual tensions, establishing supportive environments to share and discuss ideas is critical (Richard et al., 2022; Torrents et al., 2021). For instance, working in teams with common goals, aligned with each team members' motivations and interests, is key to overcome these barriers (Cheruvelil et al., 2014; Hill, Brandeau, Truelove, & Lineback, 2014). When these conditions are respected, it is usually observed that team outcomes are more creative (more original, diverse and appropriate for the defined purposes) which, in turns, benefits each members' creative development (Peng, Hunter, & Miller, 2021; Santos, Uitdewilligen, & Passos, 2015). In the current study, the second data collection took place at the beginning of the choreographic process when teams were still sorting things out. Because of the unpleasant emotions associated with this creative stage, it may have affected negatively students' perception of their ideational capacities. Yet, the improvement from mid- to post-assessment suggests that teams reorganized which impacted positively the perception of each members' ideational behaviors.

The complex interactions between the individual and its social environment may also partly explain why, descriptively, the intervention condition slightly improved the novelty dimension of emotional creativity while the control condition remained stable overtime. Emotional novelty refers to the expression of eccentric and unconventional emotions (Nezhdyan & Abdi, 2010). The Creative Dance intervention gave permission to students to express all sort of emotion through their body; many of which may usually be hindered by cultural norms and expectations. Indeed, which emotions are allowed to be expressed or not in a given context is heavily governed by sociocultural norms (De Leersnyder, Boiger, & Mesquita, 2015). According to sociocultural theories, individuals' creative expression is also influenced by social and cultural factors (Glaveanu, 2015; Glaveanu et al., 2020; Vygotsky, 2004). These interactions being dynamics, individual and environmental' changes operate on various time scales and correlate through circular causality (Balagué, Pol, Torrents, Ric, & Hristovski, 2019). Following the intervention, important social changes were reported by the interviewed students. The social connection established between participants may have helped them to publicly express unconventional emotions during the classes, which through circular causality, created even deeper social bonding. Yet, perception of cultural norms being a slow-changing constraints, time may not have been sufficient for student to feel they could express all these emotions outside of the ‘safety net’ of the class. Cultural preconceptions, such as the feeling of vulnerability when expressing emotions, probably takes more than a few months to change in an adult population (Balagué et al., 2019).

Gain in self-efficacy was an important improvement reported by participants during the interview which was supported by quantitative data. Yet, because the control condition also improved through time, non-significant interaction effect was revealed. The scale developed to assess creative self-efficacy in this study was movement specific. Because all participants were Sport Sciences students, it might be that classes undertaken by the control group impacted positively their movement creativity (e.g., sport didactics). Interestingly, besides the expansion of movement repertoire, all factors underlying self-efficacy improvements identified by the interviewed participants were non movement specific. In this vein, Quiroga Murcia, Kreutz, Clift, and Bongard (2010) showed that dance practitioners self-reported improvements in self-confidence and self-consciousness as a consequence of dancing was influenced by an enhanced sense of harmony with oneself. Beghetto and Karwowski (2017) identified three key creative self-beliefs. While creative self-efficacy pertains to ones' beliefs in their creative capacity to perform a specific task, creative self-concept refers to general beliefs about ones' creative abilities. In between these two constructs lies creative metacognition: a combination of beliefs based on one's creative self- and contextual knowledge. The specificity of creative self-efficacy measurement did not discriminate between the two conditions in the current study. Considering the ‘general’ aspects emerging from the focus groups, future studies may want to examine the impact of creative enhancement programs on creative self-concept and/or creative metacognition.

Neither the descriptive nor the mixed effects results supported improvement in tolerance to ambiguity. In fact, the control condition tolerance to ambiguity scores significantly declined compared to the intervention condition. Hence, it may be argued that Creative Dance served as a protective intervention to help students maintain their tolerance to ambiguity throughout the last semester of their first year in this Sport Sciences degree. While it is difficult to identify factors explaining the decline in tolerance to ambiguity in the control condition, qualitative analysis provides insights on how Creative Dance may be protective. Namely, participants reported being more willing to expose themselves to novelty and uncertainty in addition to let go of judgment during Creative Dance classes. Interestingly, this willingness to try different things was often associated to social connectivity. Indeed, participants better tolerated discomfort because they felt safe to explore in the group. The “brave spaces” created during the classes allowed participants to test new things without fearing to be ridiculed by others. Psychological safety is an important aspect to instill a creativity supportive environment (Edmondson & Mogelof, 2006). Participant allocated to the control condition may not have had the same opportunity to navigate such brave and safe spaces throughout the semester impacting negatively their tolerance to ambiguity.

The overall findings may have some practical implications for physical education or dance teaching. When beginners are challenged to engage in collaborative creativity processes, there may be some common processes experienced by participants that can be observed. In line with Romero-Martín and Caballero-Julia (2022) students' initial behavior model, beginners may initially feel uncertain and hesitant about participating, and they may lack confidence in their own creative abilities or worry about the judgment of others. It is important that teachers co-create a safe, supportive, and inclusive environment. Hence, providing guidance and encouragement, suspending judgment, and proposing challenges aligned with the interest of the students are key teaching behaviors. Additionally, despite the stress it may have caused, the presentation of group choreographies to the community during the Artistic Night was a very important incentive that motivated students to work together. Due to the feelings evoked by Creative Dance, beginners may take some time to adapt to the dynamics of the group. Nevertheless, as they gain experience and exposure to multiple creative tasks, they become more comfortable taking risks, generating diverse ideas, and engaging actively in the process.

Despite the applied strengths of this study, some limitations must be considered. First, the lack of statistically significant differences between conditions raises questions. While we followed Barbot's (2019) measurement recommendations to “encompass a broader range of factors that make up creativity” (p. 205), the reliance on self-report measures may still present limitations. Creative potential is a complex construct that is difficult to capture through quantitative measures based on self-report and decontextualized tools (Kaufman, 2019). Holistic approaches considering both the individual and contextual factors are required to improve assessment of creative potential changes and development (Richard, Holder, & Cairney, 2021). Hence, while costly in time and resources, integrating external observers' assessment of participants' behaviors during the whole process is a solution worth exploring. The sampling method may also explain the lack of statistical significance. Because this study was embedded in an already established course within a Sport Sciences curriculum, a disproportionate number of students were registered to the Creative Dance course that semester compared to those that were not. An imbalance in sample sizes across the intervention vs. control conditions makes detecting statistical significance challenging. Similarly, we did not have control over the distribution of participants across conditions. This absence of randomization represents another limitation of the present study. Because creative potential develops in interaction with the environment, ecological study designs are paramount. Yet, future studies must find innovative ways to circumvent the sampling challenges such design may cause. Finally, only 10 students out of 143 voluntarily participated in the focus group which limit the generalization of the qualitative findings. Integrating interviews throughout creativity development programs may be a suitable solution to include more participants and better capture changes occurring at different stages of the creative process in future studies.

CONCLUSION

In a world where “prestige goes to those who use their minds without participation of the body” (Dewey, 1934, p. 21), the power of embodied activities is often forgotten when it comes to the development of, what is considered, ‘cognitive skills’. We showed in this study that using Creative Dance to ignite individuals' creative potential is a path worthy of further explorations. According to Dewey (1934), our lives are filled with too many disembodied experiences. However, only when perceptions, sensations, emotions, and actions are reunited and supported by environmental conditions can one experienced an “expanding and enriched life” (p. 27). Creative expression being rooted in such fulfilling experiences, the inclusion of creative embodied activities to nurture creative potentials appears essential.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.