Emotional intelligence evaluation tools used in allied health students: A scoping review

Abstract

Introduction

Emotional intelligence (EI) is described as the ability to recognise and understand one's own emotions and the emotions of others, and empathically manage emotional responses. While historically not emphasised in undergraduate allied health sciences training, it is increasingly considered an essential graduate trait. This scoping review synthesises existing research on EI outcomes, specifically in undergraduate allied health professions students.

Method

Four databases were searched in February 2024 using keywords relating to EI and empathy to identify studies published in English from 1990. Eligible studies needed to include assessment and reported outcomes using validated EI tools in health professions students.

Results

A total of 163 papers met the inclusion criteria. Many studies employed a cross-sectional design (n = 115). Most studies (n = 135) focused on undergraduate students studying medicine (n = 62), nursing (n = 80) and dentistry (n = 13), with some studies (n = 21) evaluating more than one discipline. Many studies investigated one discipline only (n = 64 for nursing, n = 50 for medicine) using no comparator undergraduate degree. The most common EI models evaluated from this review were ability-based (n = 77), followed by trait-based models (n = 36) and mixed social–emotional competence (n = 35). Ability model evaluations of EI most commonly utilised the Schutte Self-Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SSEIT) (n = 44) and the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) (n = 24).

Conclusion

Research on EI among undergraduate allied health fields is limited. Existing literature reveals there is some consensus on the importance of EI in healthcare education, but there is considerable variability in how EI is measured. Studies suggest higher levels of EI may correlate with improved student professional skill development in clinical reasoning, empathy and stress management.

Introduction

Historically, higher education training of healthcare professionals (HPs) has focused on the advancement of technical and clinical skills as the driver for career success. It is a universal expectation that undergraduate health programme students will be technically and clinically competent upon entering the workforce.1-5 More recently, successful healthcare learning, including undergraduate university training, has increasingly been linked to academic achievement and students' ability to demonstrate empathetic behaviour towards patients, maintain high-level communication skills and regulate their emotional reactions.6, 7

The term HP encompasses practitioners from a wide range of healthcare disciplines, each with unique responsibilities in applying evidence-based medicine and care principles and procedures.8 Allied health professions are a diverse group of practitioners involved in the multidisciplinary care of patients. These include diagnostic radiography, nuclear medicine, nutrition and dietetics, occupational therapy, oral health therapy, podiatry, physiotherapy, podiatry, radiation therapy, sonography and speech pathology. It should be noted that this is not an exhaustive list of relevant health professionals. However, professionals in these fields engage in substantial patient interactions during their regular practice. Training typically involves 3 to 4 years of undergraduate or post-graduate training. Some disciplines may have a smaller or larger focus on patient interactions during clinical training, depending on curriculum, student progression level, clinical placements and the type of clinical sites accessed during training. These factors all contribute to individual levels of emotional intelligence (EI). EI is best described as the ability to recognise and understand one's own emotions and the emotions of others and empathically manage responses to these emotions.9

The original concept of EI was proposed by Salovey and Mayer in 1990.10 This construct is comprised of four components or abilities. These abilities include the perception of emotions within oneself and others, the capacity to generate and experience emotions as needed for expressing feelings or incorporating them into other cognitive processes, understanding and processing emotional changes and the subsequent effect on relationship dynamics and the capability to facilitate personal growth by modulating emotions both personally and in others. Trait theories of EI, as proposed by Petrides,11 focus on the individual's emotional perceptions and recognise a level of subjectivity inherent in any individual's emotional response to a given situation.

During training, and more so after qualification, the HP must be able to perceive and understand verbal and non-verbal messages and perform critical thinking to ensure optimal care delivery.12 Work-ready graduates must be able to work effectively and safely with all patients and peers in the clinical environment. Emotionally intelligent professionals are essential to healthcare practice. They ensure patient care is managed openly with empathy while maintaining critical thinking and effective decision-making.13

In areas outside health, EI is frequently recognised as a contributing factor to enhancing work quality and boosting productivity, ultimately contributing to individual and organisational achievements.14 Corporate and business sectors were early adopters of EI evaluation for recruitment, leadership development, team building and performance management.15, 16 Evidence shows that EI is also associated with emotional expression and recognition, effective mood management, stress-coping strategies and positive social interactions.

Healthcare programmes require the student or graduate practitioner to demonstrate technical clinical skill competence relevant to their field. Equally important are the non-technical skills, such as good communication, interpersonal skills, empathy and compassion, that complement these practical capabilities and enhance patient well-being. EI is one of these essential non-technical abilities that will assist HPs in providing quality care despite the emotional stressors in the workplace.17-19 Quality patient-centred care underscores the importance of partnerships between patients and healthcare providers. These partnerships facilitate flexibility in healthcare delivery by acknowledging that patient preferences, beliefs and values are essential to well-being.20 Effective communication and patient-centred care are founded on a practitioner's ability to forge meaningful connections with their patients and foster a sense of trust and understanding.21-23 These EI skills enhance patient care by reducing anxiety, building trust and strengthening patients' confidence in their healthcare providers' professionalism and support.24

EI theory encompasses four models: the ability model,10 competency model,25 trait model11, 26 and mixed model, which often combines the aforementioned models. These models offer distinct perspectives on EI and its measurement. The ability model focuses on the individual's cognitive abilities to manage and use emotions to facilitate practice.10 In contrast, the competency model emphasises personal and social competence.25 The trait model highlights individual traits involved in recognising emotions, and the mixed model takes a holistic approach to defining social and emotional competencies that affect emotionally intelligent behaviour.11, 26 The ability and trait models of EI are most commonly reported in healthcare.

In healthcare, published EI research primarily focuses on medicine and nursing programmes.27-34 Other allied health programmes, such as diagnostic radiography, radiation therapy, physiotherapy and occupational therapy, have received less attention.35-42 EI is shown to contribute to practitioner well-being, professional standards and organisational success.14, 43, 44 Studies show that EI training in students positively impacts wellness, reduces burnout and improves patient outcomes.14, 45-47 It is crucial in effective healthcare practice to promote positive interactions between HPs and patients.48

Research into EI has evolved with the development of self-reporting evaluation tools, such as the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT),49 Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SSEIT)50 and the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue).11 These measures are highly varied, from those that include only a few assessment items to more comprehensive tools. These tools differ depending on the model of EI from which they were developed.

This scoping review aims to synthesise existing research that assesses and reports on EI outcomes, specifically in undergraduate allied health profession students. This review will report on the tools used to evaluate EI in these populations as well as allied health student cohorts to assess their appropriateness. To the authors' knowledge, limited reviews of existing research in undergraduate allied health professional populations have been conducted.

Methods

This study employed a scoping review to capture the breadth of EI research in healthcare education. The purpose of a scoping review is to comprehensively examine literature sources across varied research designs within the topical framework.51 Thereby identifying any gaps in the literature that may be used to inform future research pathways. The review process adhered to PRISMA Scoping Review Guidelines.52

Search strategy

Four electronic databases, PsycINFO, Medline/PubMed, CINAHL and Embase, were searched in March 2024 to identify potentially relevant papers published from January 1990 to March 2024. This search date was based on the concept of EI first described by Salovey and Mayer in 1990.10 Papers published before this date were therefore not deemed relevant to this review. The keywords used for this search were based on previous publications and consultations with medical librarians. The search applied these keywords, synonyms and similar words to reference this topic. A copy of the full search strategy for this review can be seen in the Appendix S1.

Study selection

To be eligible for inclusion in this review, studies must have been conducted in adult populations (age > 18 years) participating in undergraduate health professional training at universities or colleges. For the purposes of this review, health professional training included medicine, nursing, midwifery, dentistry, optometry and veterinary sciences and allied health professions, including counselling, diagnostic radiography, mental health workers, nutrition and dietetics, occupational therapy, paramedicine, pharmacy, physiotherapy, podiatry, psychology, radiation therapy, social work and speech therapy/pathology. All study designs, including cross-sectional, intervention and longitudinal, were eligible for inclusion. Institutions included, but were not limited to, universities or colleges and technical or community colleges. Eligible studies needed to include assessment and reported EI outcomes using recognised and validated self-reporting assessment tools. Studies reporting outcomes from supplementary sources alongside the EI data collection were also included. Supplementary outcomes included empathy, well-being, communication and academic performance assessment. Studies were excluded if reporting only documented the foundational elements of EI, such as empathy or resilience, or were carried out in non-health-related fields such as primary and secondary education, business and health fields that do not maintain high levels of patient contact, including medical physics, biomedical engineering and laboratory science. Literature reviews (systematic, scoping or narrative), case studies, editorials and conference abstracts were excluded from this review. Relevant papers were limited to English-language publications only.

Data charting/extraction

All identified articles were uploaded to Covidence™ systematic review software for screening and data extraction. Two independent reviewers initially reviewed each article's title and abstract. If the title and abstract contained insufficient information to determine suitability for inclusion in this review, two independent reviewers retrieved and reviewed the full papers. In cases of disagreement between reviewers, details of the studies in question were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Using a customised data extraction template developed within Covidence by the research team, two reviewers independently extracted study data from full-text papers. Data extraction was initially piloted with 20 articles to ensure the aims and data required for the review were met. The data extracted included the health discipline populations studied, study design, EI evaluation tools used and alternative measures evaluated. As this scoping review aimed to comprehensively survey the available literature for measures used in the evaluation of EI, no assessment of study quality was performed. Consensus was achieved between reviewers before data extraction was finalised. Data were quantified using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, analysed and presented narratively.

Results

Search results

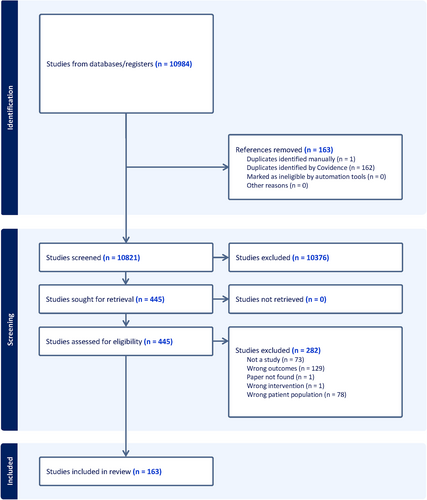

A total of 10,984 studies were identified from the database searches. Following the removal of duplicates and title and abstract screening, 445 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility using the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A breakdown of the study inclusion is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.52 A total of 163 papers were included in the final data extraction. An overview of these papers can be seen in the Appendix S2.

Study designs

The 163 EI studies forming this review were published between 2003 and February 2024. Use of EI evaluation tools in corporate or health professions may have been evidenced prior to 2003, however, the focus of this review is their use in undergraduate health and medical populations. Among the included studies, the most common study design was cross-sectional (70.6%; n = 115), followed by longitudinal cohort studies (14.7%; n = 24), ranging from 5 months to 5 years follow-up. Other study types included but were not limited to pre- and post-placement evaluations (n = 2), cohort studies (n = 4), quasi-experimental studies (n = 5) and randomised (n = 3) and non-randomised (n = 4) control trials.

Settings

The number of published studies on EI and students from medicine, nursing and allied health degrees has increased steadily since 2003. Most studies (82.8%; n = 135) included in this review included a focus on undergraduate students studying medicine (38%; n = 62), nursing (49.1%; n = 80) and dentistry (8%; n = 13). Of the included studies, many investigated one discipline only (n = 64 for nursing, n = 50 for medicine and n = 9 for dentistry) and used no comparator across undergraduate degrees. Twelve studies compared results from two disciplines, while fourteen studies included three or more comparator disciplines from health-related fields. Eight studies directly compared nursing and medicine cohorts. A small number of studies evaluated results against non–health-based disciplines such as business (n = 2), computing (n = 1), engineering (n = 1) and social sciences (n = 1). However, there is a paucity of research on allied health professional students and comparisons across multiple cohorts.

Participant characteristics

Most studies included mixed-gender cohorts of undergraduates (n = 153), with a small proportion of studies reporting female-only respondents (n = 4). In six studies, no demographic data regarding gender were reported. Selected studies contained an average of 273 students per study, with individual participant sizes ranging from 1853 to 2170.54

From the studies included in this review, there is a noted variation in the year of undergraduate study in which participants undertook the EI evaluation. The most common group was Year 1 (55.8%, n = 91). Results were reported for Year 1 students (n = 35) and in combination with other years (n = 56). Other studies focused on single-year cohorts: Year 2 (n = 7), Year 3 (n = 8), Year 4 (n = 4) and Years 5 and 6 (n = 2). Some studies had mixed-year results, such as Year 2 combined with Year 3 and 4 (8% of studies). Additionally, 25 studies did not specify the year of study for participants, while others used more general terms like ‘final year’ (n = 7) without further details about the degree duration.

EI evaluation methods

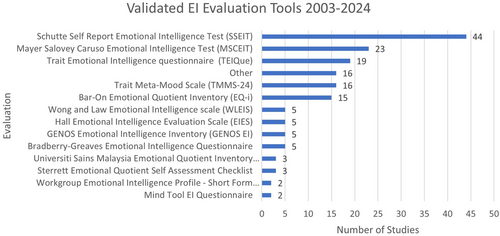

The most common models evaluated from this review were ability based (47.2%; n = 77), followed by trait-based models (22.1%; n = 36) and mixed social–emotional competence (21.5%; n = 35). Ability model evaluations of EI most commonly utilised were the SSEIT (n = 44), the MSCEIT (n = 24) and the Hall Emotional Intelligence Evaluation Scale (EIES) (n = 5). Mixed social–emotional competence methods such as the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS) (n = 16) and the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i and EQ-i2.0) (n = 15) were the next most common assessments deployed. The use of trait-based evaluation methods, including the TEIQue (n = 19) and Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) (n = 5), was reported to a lesser degree. Figure 2 shows the most common evaluation tools used in medicine, nursing and allied health.

Eleven studies reported results from evaluations combining ability, trait and mixed-model assessment methods (6.8%). The most common combinations included ability plus trait (n = 6) and ability plus mixed (n = 3) evaluations.

Secondary outcomes measured with EI

EI has been investigated as a potential predictor for academic, clinical and personal performance. Only 17.2% of the included studies (n = 28) investigated EI as a stand-alone concept. Most commonly, for the included studies, EI was assessed alongside education or training-based outcomes such as academic (20.9%; n = 34) and clinical performance (8.0%; n = 13). Some studies assessed factors complimentary to the EI model, such as empathy (11.0%; n = 18), communication (4.9%; n = 8) and alexithymia (1.8%; n = 3). There were a small number of studies that also considered aspects related to student well-being, including stress (11.7%; n = 19), anxiety (5.5%, n = 9), mental health (4.3%; n = 7) and depression (3.1%; n = 5).

Discussion

In the literature, EI has been defined as both an ability and a trait.55 The Salovey and Mayer ability theory of EI refers to the capability to recognise and adapt to emotional change within oneself and others, such as patients.9 Schutte further highlighted EI as a non-cognitive ability essential to understanding, analysing and regulating emotional knowledge and responses.50 Johnson48 identified that the components of ability EI models can be addressed as vital aspects of the patient–clinician relationship. As such, this suggests that EI from an ability perspective, much like any clinical skill, can be taught and therefore learned. Trait EI theory concerns an individual's perception of their own emotional regulation abilities and recognises that their emotional response to a given situation will be variable.11 As this theory assumes an inherent response, it links to mental ability rather than a learned response.

This scoping review synthesises data from existing research reporting on measured EI outcomes in undergraduate health professional students. The main findings from this review identified that the number of research studies investigating EI has increased steadily since the proposal of EI theory in 1990. Many published studies have investigated EI in the commencing years (Years 1 and 2) of undergraduate study, with the most common studies in the health professional group being undertaken for nursing, medicine and dentistry, accounting for 84% of papers. Comparatively, there are fewer reported studies in other health-related fields. Nursing and medicine groups may be more commonly investigated because nursing and medicine are considered caring professions that often have large cohort sizes and high levels of patient exposure during training.

Nursing and medical professions are central to patient-centred care. Birks and Watt14 proposed that EI underpins patient-centred care. A number of studies in nursing and medicine also suggest that EI relates to patient care traits like compassion,56, 57 empathy,54, 58-71 clinical reasoning72 and communication73-76 among health workers.

Study cohorts – allied health

Research studies in allied health alone (excluding medicine, nursing and dentistry) accounted for only 11.7% of research,35-42, 77-87 with an additional 4% of studies collecting data for allied health alongside medicine, nursing and dentistry cohorts.67-69, 88-91 This highlights that allied health profession students are underrepresented in the EI research and warrant further research in future studies. Existing research on EI evaluated in this review is mainly cross-sectional (68%) and often only conducted within a single cohort of health professional students (64%). As primary health caregivers, nursing and medical students have been the focus in 56% of these studies. As cross-sectional studies collect data from the same population at one period of time only to understand the prevalence of a particular attribute or association, subjects are often drawn from large and heterogeneous populations.92 Therefore, large student cohorts in medicine and nursing degrees likely present ideal convenience samples to attract large numbers appropriate for the cross-sectional study to understand potential relationships and associations with other factors, such as academic and clinical performance, as found to be commonly assessed alongside EI in this review. Comparatively, allied health degrees tend to have smaller student cohorts and were often used only as a comparator group for the primary cohorts in nursing or medicine rather than as the main focus of the evaluation.45, 68, 69, 89-91, 93-95 This is an underexplored area for EI compared to its nursing and medical student peers. Given the equivalent levels of patient contact and clinical placement hours demonstrated by allied health students, it would also be expected that EI levels will increase over the course of undergraduate degree training.

This review includes studies with a comparator group unrelated to health professions, such as engineering or business students.39, 40, 90, 96, 97 These comparator groups potentially provide significant number of participants who serve as a control group to students who have direct patient contact during their studies. Gribble40 hypothesised that due to limited or no enforced contact with a patient or client cohort during their academic studies, business students would demonstrate lower levels of EI compared to students in therapy-based health degrees. Comparator groups were also used in some studies to compare gender differences in EI results, such as comparing engineering or business cohorts with predominantly male students to nursing degrees that traditionally have a dominant female population.40, 96, 97

A number of studies have compared changes in EI over time with the expectation that EI will develop during the specified period. Students involved in these studies may have had structured learning tasks or have shown development through experiential clinical learning. However, mixed results have been reported.35, 36, 38-40, 88, 89, 96, 98-101 For example, studies examining students across the entirety of their degree have reported positive improvements in EI when accompanied by immersion in clinical environments, particularly in medicine and nursing.39, 89, 98 In addition, clinical scenarios used during on-campus education to supplement placement experiences have shown improvements in EI and related skills (e.g. assertiveness, problem-solving and stress tolerance) in more than 60% of physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech pathology students.35, 40 Adding mindfulness and self-esteem training into the curriculum has yielded favourable results for EI improvement over time.96, 99 In contrast, studies in osteopathic medicine students report declines in EI and empathy levels between baseline data collection and the final stages of student learning, warranting the potential need for EI to be addressed within the curriculum.38, 100 A small number of longitudinal studies reported little to no significant change in EI across their undergraduate training for diagnostic radiography and radiation therapy students,36 and nursing, dental and medical student cohorts.88 Specific reasoning for the lack of EI growth was unable to be determined in both cases but may be attributed to limited specific EI training within the curricula.36

EI outcome measures

The selection of an EI evaluation tool depends on the EI theory and properties being studied.102 These tools are generally self-reporting, requiring Likert-style responses to questions. However, self-reporting tools rely upon a person's ability to assess their abilities accurately, which could lead to unreliable results when participants respond with socially acceptable rather than true answers.103 Tools require participants to respond to emotion-related situations or report on their understanding of perceived emotions.49, 103

No studies using EI evaluations in health or medical student populations before 2003 were identified in this review. Since 2003, the variety of tools and their respective usage in undergraduate health and medical populations has increased steadily. Following data review, ability-based models of EI assessment, such as the SSEIT50 and the MSCEIT,9 are the most common evaluation tools for undergraduate medical and nursing students. This aligns with Bru-Luna's104 results from a systematic review evaluating EI measurement tools across a ‘professional’ population which is inclusive of business and education but not limited to healthcare. This would indicate that future research using these tools in allied health student populations may yield comparable results.

In line with Snowden et al., the advantage of using evaluations using a combination of models would be to capture a more comprehensive understanding of EI within the individual participant.96 The different models of EI have shown conceptual similarities. Trait-based assessments provide insights into how individuals perceive and describe their emotional management skills.11 Conversely, ability-based evaluations measure the individual's actual performance in scenarios related to EI and may provide a more objective assessment of the participant's EI skills.10, 50 O'Connor et al. proposed that selecting a single EI tool would facilitate intervention models based on the foundation theories.103 It could be surmised that combining trait- and ability-based evaluations could achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the individual's EI skills and enable exploration of the data most relevant to the researchers' requirements. However, multiple foundational theories of EI and related evaluation tools may impose increased complexity on any study and future interventional measures.103

In health-based EI research, several studies have evaluated multiple EI models within a single study. Borges105 compared the results in three medical school cohorts using three different measures (Bar-On EQ-I, TMMS mixed measures and MSCEIT ability measure). Results yielded similarity in EI results across the cohorts evaluated. Seven studies directly compared results using both an ability-based EI evaluation (e.g. MSCEIT or SSEIT) and trait-based evaluation (e.g. WLEIS or TEIQue).96, 97, 106-109 Snowden et al.96 suggested that measuring different EI concepts would yield more comprehensive and reliable profiles than using singular measures alone in nursing students. In the first phase of this longitudinal study, the mean scores from each type of test were comparable, with the only notable result being that EI may increase with age, nursing students performed better than non-nursing students and mindfulness may be associated with the ability EI concept.96 Studies by Stiglic et al.97 and Stenhouse et al.107 reflect these findings. Gutman and Falk-Kessler79 compared differing ability-based evaluation tools in the SSEIT Likert-style self-reporting tool with the Emotional Intelligence Admission Essay Scale, while Alkhadher84 and Doherty55 compared the ability model alongside mixed methods testing.

The 24 longitudinal studies in this review suggest that an ability-based EI assessment model would be most suitable for examining EI within undergraduate student cohorts engaged in health studies.35, 36, 38-40, 55, 56, 66, 88, 89, 96, 98-101, 107, 110-115 The objective of such a study would be to evaluate the evolution of EI skills from the commencement to the conclusion of a degree, considering various amounts of exposure to clinical environments during this period. Varied results were noted among the longitudinal studies, with almost 50% documenting moderate-to-significant improvements in EI over 1 to 5 years, with some correlation to clinical placement experience.35, 39, 40, 56, 66, 89, 96, 98, 99, 101, 111, 112 However, there were a small number of studies that demonstrated no significant change in EI levels in an evaluation both in a period of less than 12 months88, 114 or 2–3 years.36, 55 Mintle et al.100 and Singer-Chang et al.38 reported decreases in EI levels across the given degree and hypothesised that decreased levels could be counteracted by adding EI content or coaching into the curriculum. Stenhouse et al.107 proposed that increasing levels of EI during an undergraduate degree were not indicators of clinical performance. However, Gribble et al.35 noted fluctuations in EI before and after clinical placement, with more significant increases reported when EI coaching or mentoring is added to the curriculum.39, 40

Given that EI is theorised as a learned ability,9 similar to acquiring any other technical skill, it logically follows that ability-based measures would be the most relevant for longitudinal data collection within health-related disciplines. For example, the SSEIT,50 which is fundamentally based on the Salovey and Mayer10 concept of EI, perceives EI as a learnable ability that can be developed and enhanced over time, implying that this is a suitable assessment method in these cohorts. This is evidenced by 32% of studies referenced in this scoping review using the MSCEIT or SSEIT as the primary tool for data collection.56, 76, 88, 98, 107, 110, 111, 114

Although limited longitudinal studies examine changes in EI over time within specific programmes, there are notable examples. In a 5-year follow-up study by Ranasinghe et al.,98 170 medical students were evaluated using the SSEIT ability EI test at the beginning of their studies and again before matriculation. Significant experiential increases in EI scores were noted from the baseline to follow-up independent of gender, ethnicity, religion, socio-economic parameters or academic performance.98 Abe et al.112 reported increases in EI scores and medical student confidence in dealing with emotional issues at a 1-year follow-up after a combined mental health and EI workshop.

Secondary outcomes measured with EI – academic, clinical and student well-being

EI is a multifaceted construct that plays a significant role in shaping work attitudes and practices in healthcare workers.116 This impact will span academic performance, clinical practice and overall well-being when considering healthcare students. Only 17.2% of the studies included in this review focused solely on EI.31, 35, 36, 39, 40, 67, 74, 75, 79-81, 96, 97, 105, 111, 117-129 The remainder explored the relationship of EI to a variety of other outcomes, including personality41, 68, 78, 84, 106, 112, 113, 130-135 and professionalism.37, 134

EI has garnered attention as a potential predictor of academic success. Studies that explored this relationship often assessed EI alongside educational outcomes. For instance, 34 studies examined how EI influenced academic performance and investigated whether students with higher EI performed better in their studies.23, 29, 32, 37, 55, 56, 62, 76, 90, 98, 100, 107, 113, 114, 118, 134, 136-153 Managing emotions, understanding others and navigating social situations could potentially contribute to improved learning outcomes. Beyond academia, EI also plays a role in clinical settings. Approximately 8.0% of the studies examined EI in the context of clinical performance.37, 41, 47, 56, 76, 77, 82, 137, 139, 144, 152, 154, 155 Healthcare students with strong EI may exhibit better patient communication,27, 62, 73, 154, 156-159 empathy58-63, 67-70 and teamwork.69, 78, 105, 160 These qualities are crucial skills for a student to develop to foster effective healthcare delivery principles upon completion of their training.161

While EI is a multifaceted construct, some studies explored related factors. Empathetic individuals can connect with others emotionally, which is essential in various contexts, including education and healthcare.42, 54, 58, 59, 62-71, 83, 86 Effective communication skills enhance collaboration and understanding.27, 62, 73, 154, 156-159 Alexithymia refers to difficulty identifying and expressing emotions. Understanding how alexithymia interacts with EI can provide valuable insights.58, 86, 162

A smaller subset of studies considered student well-being, including aspects such as stress,30, 42, 45, 87, 88, 91, 110, 131-133, 144, 156, 160, 163-174 anxiety,30, 85, 86, 131, 162, 163, 175-177 mental health53, 84, 85, 177-180 and depression.30, 85, 131, 175, 177 EI may influence how students cope with stressors, manage anxiety and maintain mental well-being. High levels of EI could potentially mitigate the negative impact of stress and emotional challenges.87, 88, 98

Limitations of current literature

This scoping review has identified several gaps in the literature. Primarily, limited data evaluate and compare EI in undergraduate allied health students. The investigation of allied health disciplines as a primary data source is limited, with occupational therapy39, 41, 77, 79, 80 and physiotherapy35, 40, 83 undergraduates forming the data source. Additional allied health studies have compared physiotherapy, occupational therapy, podiatry, paramedicine, nutrition and dietetics with medicine and/or nursing and midwifery.45, 68, 89-91, 93, 94 Only two studies producing results from diagnostic radiography and radiation therapy36 and podiatry37 were evident.

Secondary to this, there is a paucity of longitudinal data recorded. Most studies included cohorts of first-year students. As a baseline for data collection, the evaluation of Year 1 students will mostly reflect the participant's life experience and not identify any development of EI in the individual either from participating in EI development programmes or immersion in clinical placement. Additional longitudinal data across cohorts would better reflect this.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review used rigorous methods to determine what is known about EI in undergraduate allied health students from existing literature and to identify gaps in published literature.181 There is limited literature that reports on EI and associated elements in undergraduate allied health students, identifying this as an area suitable for further future investigation.

This scoping review did not utilise a quality assessment tool to evaluate the methodological rigour and quality of the included studies. However, this is consistent with other scoping review protocols. The absence of quality assessment evaluation in a scoping review may lead to the inclusion of biased or less objective studies, potentially impacting the reliability and validity of the reviewer's findings and conclusions. Only English language studies are included. EI evaluation uses self-report measures that rely on participants' perceptions of their beliefs, attitudes and behaviours.

Conclusion

Research on EI among undergraduate students in allied health fields is not as extensive as it is for medical and nursing students. Existing literature reveals that while there is some consensus on the importance of EI in healthcare education, there is considerable variability in how EI is measured. Studies suggest that higher levels of EI may correlate with improved professional development for students in clinical reasoning, stress management and empathy. Various EI tools could be considered when evaluating this concept in undergraduate health students, but the tool selection should be founded on the EI theory under investigation. Secondary data collection and analysis related to student academic or clinical performance, or complimentary skill sets related to EI may be warranted in future studies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in the completion of this study.

Ethics

This project has been approved by the University of Newcastle's Human Research Ethics Committee, Approval No. H-2022-0383.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.