Significance of ileal and/or cecal wall thickening on abdominal computed tomography in a tropical country

Abstract

Background and Aim

Clinical significance of ileocecal thickening on computed tomography (CT) is uncertain. We conducted this prospective study to determine the clinical relevance of ileal and/or cecal thickening on CT.

Methods

All patients with ileocecal thickening on CT were prospectively evaluated with ileocolonoscopy, biopsy, and other relevant investigations.

Results

Fifty patients (29 males, mean age 36.8 ± 13.21 years) were studied. Thirty nine (78%) patients presented with abdominal pain. On CT, 46 (92%) had a thickened wall of terminal ileum, 25 (50%) cecum, and 21 (42%) of both cecum and ileum. The mean wall thickness of ileum and cecum on CT was 7.23 + 3.2 mm and 5.5 + 3.1 mm, respectively. Final diagnosis was tuberculosis in 24 (48%) patients, Crohn's disease (CD) in 10 (20%), and adenocarcinoma in 1 patient. Colonoscopy demonstrated abnormal findings in 41 patients (82% patients with mucosal ulcerations being most common (n = 20 (40%). Of 15 (30%) patients with ileocecal bowel wall thickening, 4 (8%) patients had normal colonoscopy and histopathology (incidental ileocecal wall thickening), and in the remaining 11 patients, histopathology showed non-specific findings and these patients were asymptomatic without any specific treatment on last follow up ranging from 3 to 24 months. Involvement of cecum with ileocecal junction, ascending colon involvement, peri-ileocecal stranding, and long-segment stricture was significantly more common in patients with underlying disease as compared to nondiseased patients (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

A majority of patients with ileocecal wall thickening on CT have an underlying disease and should be further investigated by ileocolonoscopy and biopsy.

Introduction

Multidetector computerized tomography (MDCT) has the capability of generating high-resolution, multiplanar reconstruction images and has thus become an important tool in the detection and characterization of bowel abnormalities. It allows assessment of both mural and extraluminal abnormalities.1, 2 Thickened bowel wall is a common finding on MDCT in patients with abdominal pain, and it suggests a possible bowel disease responsible for the gastrointestinal symptoms. However, the differential diagnosis in this situation is wide, ranging from nonspecific abnormality to malignancy.

The normal small bowel wall thickness on computed tomography (CT) depends on the bowel distension, and in an adequately distended small bowel, the wall thickness of 1–2 mm is considered to be normal. However, if the small bowel is underdistended, the wall thickness may measure up to 3 mm.3, 4 Similarly, the colonic wall should measure less than 3 mm when the lumen is well distended to 5 mm when the lumen is collapsed.3-5 The bowel wall thickening may be caused by several diseases, which may include neoplastic, inflammatory, infectious, or ischemic conditions or may be a normal variant. Several CT features, such as the length of involvement; degree of thickening; symmetric versus asymmetric involvement; pattern of attenuation; and presence of peri-intestinal abnormalities like enlarged lymph nodes, mesenteric stranding, abscess and sinus tracts, fatty proliferation, and solid organ abnormalities, are used for differential diagnosis.1-5

The ileocecal area is a relatively short segment of the gastrointestinal tract but may be affected by a wide variety of pathological conditions that result in the thickening of the wall of the ileocecal tract. In tropical and developing countries, infective diseases like tuberculosis (TB) may also result in ileocecal wall thickening and thus expand the list of differential diagnosis. Sometimes, poor distension of the bowel may be erroneously reported as bowel wall thickening. Although various features on CT are used for differential diagnosis, ileocolonoscopy and biopsy is required in the majority of patients to correctly diagnose the underlying pathology.1-5

The causes of small bowel or ileocecal thickening have been infrequently evaluated. A retrospective study of medical records of patients with small bowel thickening on CT of the abdomen and pelvis over a 1-year period found that infectious and inflammatory (primary or reactive) conditions were the most common cause of small bowel thickening.6 In another study, 33 of 40 patients (83%) with small bowel wall thickening had inflammatory etiology.1 However, to the best of our literature search, the clinical significance of ileocecal thickening on CT has not been prospectively evaluated. We conducted this prospective study to determine the significance of ileocecal thickening on CT by performing ileocolonoscopy and biopsy in these patients.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted on patients seen in outdoor or indoor services of our unit at a tertiary care center in North India from June 2014 to December 2015. All patients seen during this period with terminal ileum, cecal, or ileocecal thickening reported on CT abdomen were enrolled in the study. All patients provided informed consent before enrolment, and the study protocol was approved by the institute's ethics committee. Patients not giving consent; unstable patients unable to undergo colonoscopy; pregnant females; patients with significant cardiovascular disease, coagulopathy, or thrombocytopenia; patients with previously diagnosed ileocecal disease; and patients with known malignancy were excluded.

After enrolment, detailed clinical history was taken, and clinical examination findings were recorded. The laboratory tests were performed by the treating clinician and were recorded by the investigators. All the patients underwent colonoscopy and ileoscopy after oral preparation with 4 L of polyethylene glycol. Morphological findings of intestine during endoscopy, including normal, skip lesions; deep ulcers; aphthous ulcers; fissures; fistula; cobble-stone appearance; stricture; and site of involvement, were carefully identified and noted. The endoscopic pinch biopsies were taken from the ileum and cecum in all the patients and were subsequently mounted on filter paper and sent for histopathological examination.

Histological findings were evaluated using paraffin-embedded tissue specimens after staining with HE. The histology of all specimens was reported by an experienced pathologist, who was unaware of the clinical, morphological, and laboratory findings. The histological features were examined for the presence of ulceration of surface epithelium; appearance of crypts; presence of lymphoid aggregates; and site and type of inflammatory infiltrate, granuloma, and characteristics of granuloma (caseation or confluence). Biopsy specimens were subjected to Ziehl-Neelsen smear for acid-fast bacilli when suspected. Any other special staining, if deemed necessary for arriving at a diagnosis, was also performed.

CT abdomen was carefully evaluated by an experienced gastrointestinal radiologist Naveen Kalra (NK) for CT features such as the length of involvement; degree of thickening; symmetric versus asymmetric involvement; pattern of attenuation; and presence of peri-intestinal abnormalities like enlarged lymph nodes, mesenteric stranding, abscess and sinus tracts, fatty proliferation, and solid organ abnormalities. The final diagnosis of the disease was based on clinical, imaging, endoscopic, and histopathological findings as well as a response to appropriate treatment.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed for three groups, namely, terminal ileal, cecal, or involvement of both with and without ileocecal junction (ICJ) involvement on CT. Continuous variables were presented as mean, median, standard variation, and range. Categorical data and proportions were compared using Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Fifty symptomatic patients (mean age of 36.8 ± 13.21 years; 29 M) who were detected to have ileocecal wall thickening on abdominal CT were prospectively studied. The most common symptom with which patients presented was abdominal pain (78%), followed by weight loss (72%), fever (44%), diarrhea (30%), and bleeding from the rectum (10%). Fourteen (28%) patients had a history of one or more episodes of subacute intestinal obstruction (SAIO). A palpable abdominal lump in the right iliac fossa was present in six (12%) patients.

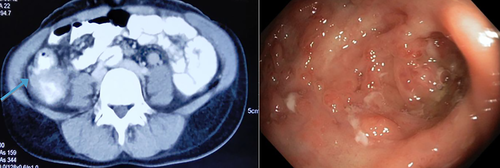

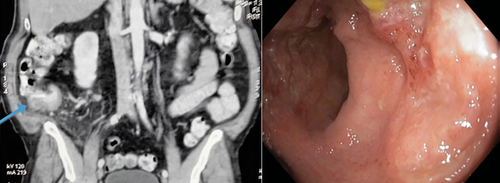

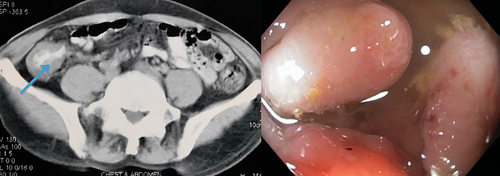

On CT, 46 (92%) patients had thickening of terminal ileum, 25 (50%) of cecum, and 21 (42%) of both cecum and ileum; ICJ was involved in 34 (68%) patients, and 6 (12%) patients had ascending colon involvement (Fig. 1-3). Of the six patients with ascending colon involvement, four patients also had involvement of all the other three regions—ileum, ICJ, and cecum. Peri-ileocecal stranding was seen in 31 (62%) patients. Mesentric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy with lymph node size >1 cm was seen in 11 (22%) patients and small lymph nodes (<1 cm) in 12 (24%) patients. A hypodense center in the large lymph nodes was observed in 3 of 11 (27%) patients. In 2 of 11 (18%) patients, calcification in the lymph node was seen. Locoregional lymph nodes more than 1 cm in diameter were seen in 18 (36%) patients, and small (<1 cm) lymph nodes were seen in 26 (52%) patients. A hypodense center and calcification were seen in two and three patients with locoregional lymphadenopathy, respectively. Stricture (>3 cm), as evident by thickening and proximal dilatation, was seen in 10 (20%) patients, and the other 80% of patients only had thickening (>3 cm) without proximal dilatation. The mean wall thickness of ileum and cecum on CT were 7.23 + 3.2 mm and 5.5 + 3.1 mm, respectively.

All 50 patients underwent colonoscopy. The cecum could be seen in all 50 patients, but ileoscopy could be performed in 46 patients as 4 patients had narrowing at ICJ, and the ileum could not be intubated. The mean length of ileum that was seen was 5.3 + 2.3 cm. We found abnormal findings on colonoscopy in 41 (82%) patients. The most common finding was mucosal ulcerations, seen in 20 (40%) patients (large ulcers—3 patients and aphthous ulcers—17 patients), and the mucosa surrounding ulcer showed a loss of vascular pattern in 15 (30%) patients (Fig. 1-3). Other findings observed were nodularity in five (10%) patients, polypoidal lesions in three (6%) patients, and ileocecal valve narrowing in four (8%) patients.

In nine (18%) patients, colonoscopy was normal despite changes on CT. However, histopathological examination of the mucosal biopsy demonstrated abnormal findings, with four patients being diagnosed with TB and one patient having Crohn's disease (CD). The histopathological findings in the remaining four patients were also normal, and these patients were asymptomatic on last follow up.

On histology, granulomas were seen in 16 (32%) patients. Of these patients, microgranulomas (>200 μm) were seen in 12 patients (9 TB/3 CD), and macrogranulomas (>200 μm) were observed in 3 patients who were diagnosed with TB. Of the 24 patients diagnosed with ileocecal TB, acid-fast bacilli positivity was seen in 1 (4%) patient. Other findings on histology included ulcerated epithelium, abnormal crypt architecture with features of chronicity, lymphoid follicles in CD and lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate, granuloma, epithelial ulcerations, and submucosal edema in TB. Three (6%) patients had mycobacterium TB DNA detected on polymerase chain reaction.

The final diagnosis was TB in 24 (48%) patients, CD in 10 (20%) patients, and adenocarcinoma in 1 (2%) patient. In 15 (30%) patients with ileocecal bowel wall thickening, 4 (8%) patients had normal colonoscopy and histopathology (incidental ileocecal wall thickening), and in the remaining 11 patients, histopathology showed nonspecific findings not attributable to a particular pathology, and these patients were asymptomatic without any specific treatment on last follow up ranging from 3 to 24 months (Table 1).

| S. no | Colonoscopy | Histopathology | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal colonoscopy | Normal histology | Asymptomatic |

| 2 | Normal colonoscopy | Normal histology | Asymptomatic |

| 3 | Normal colonoscopy | Normal histology | Asymptomatic |

| 4 | Normal colonoscopy | Normal histology | Asymptomatic |

| 5 | Aphthous ulcer and nodularity in ileum | Intact lining epithelium; moderate lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate with plasma cells, eosinophil, and neutrophils. | Asymptomatic |

| 6 | Loss of vascular pattern in ileum and cecum and aphthous ulcers | Focally ulcerated epithelium. Scattered epitheloid histiocytes in submucosa |

Asymptomatic |

| 7 | Ileocecal valve bulky | Intact lining epithelium. Mild lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate. | Asymptomatic |

| 8 | IC valve bulky, cecal aphthous ulcer and diverticula | Intact lining epithelium, mild lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate | Asymptomatic |

| 9 | Gaping IC valve | Intact epithelium, mild lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate | Asymptomatic |

| 10 | Gaping IC valve, loss of vascular pattern in cecum | Intact epithelium, mild lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate | Asymptomatic |

| 11 | IC valve nodularity | Intact epithelium, focal cryptitis, mild edema, and mild lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate with eosinophils | Asymptomatic |

| 12 | Aphthous ulcers in ileum and cecum with loss of vascular pattern in surrounding mucosa | Ulcerated lining epithelium, mild lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate. Acute inflammation | Asymptomatic |

| 13 | Aphthous ulcer in ileum and IC valve ulcerations | Ulcerated lining epithelium, mild lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate with lymphoid aggregates | Asymptomatic |

| 14 | Aphthous ulcers with nodularity in surrounding mucosa | Ulcerated lining epithelium with focal cryptitis. | Asymptomatic |

| 15 | Normal colonoscopy | Intact lining epithelium, mild lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate | Asymptomatic |

- IC, ileocecal.

CT and clinical characteristics of diseased versus nondiseased patients

After evaluation, 35 patients were found to have underlying pathology, and 15 patients had either normal histology or nonspecific findings on histology with uneventful follow-up period.

Clinical features

It was observed that presence of fever, weight loss, organomegaly, history of SAIO, and diarrhea was more common in the diseased group (Table 2). History of bleeding from the rectum, peripheral lymphadenopathy on examination, and ascites, when present, had a definite pathological diagnosis. However, only diarrhea was significantly more common in the diseased group in comparison to the nondiseased group.

| S no. | Clinical features | Group A (nondiseased/nonspecific) n = 15 (%) | Group B (diseased) n = 35, (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pain abdomen | 12 (31) | 27 (69) | 0.823 |

| 2 | Fever | 7 (46) | 15 (42) | 0.824 |

| 3 | History of SAIO | 4 (26) | 10 (28) | 1.000 |

| 4 | Diarrhea | 1 (7) | 14 (40) | 0.018 |

| 5 | Constipation | 7 (47) | 8 (23) | 0.092 |

| 6 | Weight loss | 8 (53) | 28 (80) | 0.054 |

| 7 | Loss of appetite | 9 (60) | 23 (66) | 0.700 |

| 8 | Bleeding per rectum | 0 (0) | 5 (14) | 0.123 |

| 9 | Peripheral lymphadenopathy | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0.508 |

| 10 | Abdominal distension | 4 (26) | 6 (17) | 0.440 |

| 11 | Tenderness | 1 (25) | 8 (17) | 0.704 |

| 12 | Organomegaly | 1 (6) | 5 (14) | 0.585 |

| 13 | Ascites | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 0.191 |

- SAIO, subacute intestinal obstruction.

CT features

On comparison of CT findings between the two groups, involvement of cecum with ICJ, ascending colon involvement, peri-ileocecal stranding, and long-segment stricture were significantly more common in patients with an underlying disease process compared to nondiseased patients (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| S. no | CT involvement | Nondiseased /nonspecific, n = 15 | Diseased, n = 35 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ileum | 15 (100) | 31 (88%) | 0.539 |

| 2 | ICJ | 11 (73) | 23 (65%) | 0.754 |

| 3 | Cecum | 7 (46) | 18 (51%) | 0.546 |

| 4 | Ileum + ICJ | 4 (27) | 7 (20%) | 0.880 |

| 5 | Cecum + ICJ | 0 (0) | 2 (5%) | 0.000 |

| 6 | Ileum + cecum + ICJ | 7 (46) | 14 (40%) | 0.735 |

| 7 | Ascending colon | 0 (0) | 6 (17%) | 0.045 |

| 8 | Peri-ileocolic stranding | 1 (9) | 24 (68%) | 0.032 |

| 9 | Regional lymphadenopathy | 6 (40) | 12 (34%) | 0.633 |

| 10 | Long-segment stricture | 0 (0) | 10 (18%) | 0.046 |

| 11 | Mesentric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy | 3 (27) | 6 (12%) | 0.159 |

- ICJ, ileocecal junction.

Discussion

CT, especially after the advent of multidetector helical scanning, has led to the increased detection of subtle gastrointestinal tract abnormal findings.1 Bowel wall thickening is one of the important gastrointestinal tract abnormalities increasingly being detected on CT.1 The bowel wall thickening could be a manifestation of underlying inflammatory, infectious, ischemic, or neoplastic pathology or may represent normal findings because of technical reasons, such as inadequate distension of the bowel. Previously, the significance of colonic wall thickness was evaluated by various studies, and most of the studies have concluded that patients with colonic wall thickness on CT should undergo colonoscopy and biopsy as a majority of these patients will have an underlying disease.1-15 This recommendation of endoscopy has been made because of the increased risk of neoplastic diseases in the colon. However, the significance of ileocecal wall thickening on CT has been infrequently evaluated. In the current study of 50 patients with ileocecal wall thickening on CT, we found that 82% of patients had abnormal findings on colonoscopy, and 70% of patients had underlying inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic disease, leading to bowel wall thickening.

Iadicola et al. studied 40 patients with bowel wall thickening on CT and found that 72.5% of patients had significant underlying pathology causing bowel wall thickening. Of nine patients with small bowel thickening, 33.3% patients had an ischemic disease, 33.3% nonspecific pattern, 22.2% an inflammatory disease, and 11.1% were diagnosed with cancer.16 In contrast, Tellez-Avila et al. found normal endoscopy in 61% patients with incidental gastrointestinal luminal wall thickening on CT.17 The higher frequency of normal endoscopy in this study could be because of the inclusion of asymptomatic patients. Min et al. evaluated 56 children presenting with abdominal pain and thickened bowel wall on CT scan, and of these 56, 30 (54%) had terminal ileum wall thickening, 17 (30%) had isolated colonic wall thickening, and 9 (16%) had other involvement of other areas of the small bowel wall.18 Of these, 21 (38%) underwent endoscopy, and 14 (67%) had positive findings (11 [79%] with chronic colitis and 5 [36%] with duodenitis/ileitis). The final diagnosis in these 56 patients was: 11 (20%) with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), 8 (14%) with functional abdominal pain/constipation, 9 (16%) with appendicitis, 10 (18%) with infectious gastroenteritis, and 18 (32%) with a miscellaneous diagnosis. The authors concluded that the presence of thickened bowel wall on CT scan is a nonspecific finding in children.

Al-Khowaiter et al. studied 76 symptomatic patients with terminal ileal and/or colonic wall thickening and found that 76% of patients had various identifiable pathologies on colonoscopy, whereas 24% had normal colonoscopy.8 In their study, IBD and infectious colitis were the most common causes of bowel wall thickening. We also found that 68% patients had an IBD, 2% had cancer, 8% patients had normal colonoscopy and histopathology (incidental ileocecal wall thickening), and 22% patients had nonspecific findings not attributable to a particular pathology. The higher frequency of inflammatory diseases in our study could be because of the increased frequency of intestinal TB in developing countries like India.

On comparing CT features between the diseased and normal patients, we found that the involvement of cecum with ICJ and ascending colon, peri-ileocecal stranding, and long-segment stricture were significantly more common in patients with underlying disease. Al-Khowaiter et al. reported that “skip lesions” on CT (5%) were always associated with IBD.8 On the other hand, pancolitis reported on CT (11%) was associated with IBD in 25% of cases, infection in 50% of cases, and normal findings in 25% of cases. Stranding and regional lymphadenopathy were reported in both diseased as well as normal groups. However, we found that ileocecal stranding was significantly more common in the diseased group, but reports of lymphadenopathy were similar in both the groups. Min et al. reported that children with a final diagnosis of IBD had a significantly higher frequency of abnormal erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, albumin, and platelet count compared to the non-IBD group.18

CT has inherent limitations in evaluating the gastrointestinal lumen as underdistention of the bowel, and oblique planes may lead to erroneous interpretation of bowel thickening.5, 19 However, the advent of newer technologies such as multidetector CT have improved the diagnostic accuracy of CT. Still, four (8%) of our patients with bowel wall thickening on multidetector CT had normal colonoscopy and histopathology.

Our study is probably the first study that has prospectively assessed the significance of ileocecal thickening on CT in patients from a tropical country where a significant number of small bowel diseases are caused by infections. We studied 50 patients, and all patients underwent colonoscopy with a follow up of up to 24 months. Despite these strengths, being a single-center study from a tertiary care center catering to referred patients was a major limitation of our study.

In conclusion, the majority of patients with ileocecal wall thickening on CT has an underlying disease and should be further investigated by ileocolonoscopy and biopsy. Involvement of cecum with ICJ and ascending colon, peri-ileocecal stranding, and long-segment stricture suggest the presence of an underlying disease.