How do students negotiate groupwork? The influence of group norm exercises and group development norms

Abstract

Background

Group norms in engineering education groupwork are usually negotiated in an implicit and often unequal manner. Although it is regularly suggested that student groups can function better if norm negotiations are, instead, made explicit, the social dynamics of group norm exercises have remained underexplored.

Purpose

We investigate how students negotiate group norms in group norm exercises, including the different understandings of groupwork that they construct and draw from to facilitate their negotiations.

Method

We recorded and analyzed a sequence of three group norm exercises focused on developing a team charter, with seven participating student groups. Drawing on framing theory, we study negotiation sequences in terms of framing practices, and understandings of groupwork in terms of activity frames.

Results

Our findings suggest that group norm exercises can help students to coordinate their expectations and transform previously established norms. However, they may also be approached in such a way that students are discouraged from questioning established group norms, instead resolving disagreement by simply rejecting alternative perspectives. We introduce the term “group development norms” to explain these dynamics, showing that the question of how to develop group norms is in itself a subject for negotiation.

Conclusions

Providing a forum and process is neither enough to ensure reflective and equitable negotiations nor transparent and inclusive group norms. To avoid that group norm exercises simply reaffirm dominant norms, students should be provided with explicit negotiation strategies and, ideally, direct facilitation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Many engineering programs feature a range of groupwork experiences, with formats spanning from small-scale problem solving to extensive capstone design projects (Chen et al., 2021; Pembridge & Paretti, 2019). Despite research showing that these groupwork experiences may involve problematic interaction patterns between students (Fowler & Su, 2018; Pieterse & Thompson, 2010; Tonso, 2006), student groups are often left to their own devices when it comes to developing productive group norms (Beddoes & Panther, 2018; Paretti et al., 2014). Among the variety of factors that influence how groups then develop, up-close studies have shown how group norms are established through continuous negotiations between students as they work together (Fowler & Su, 2018; Wieselmann et al., 2020). That is, by talking about groupwork, about engineering, and about each other in particular ways, students establish certain relationships and standards that group members are expected to maintain (Pattison et al., 2018; Shim & Kim, 2018). Rather than being expressed directly, these expectations are often communicated in a subtle and implicit manner (Herro et al., 2021; Mathieu & Rapp, 2009).

Accordingly, in the cases where educators do actively support students in becoming well-functioning groups, it has become a common practice and recommendation to facilitate group norm exercises, where student groups are tasked with explicitly discussing their groupwork and agreeing on how to collaborate. These exercises are often structured around the creation of a “contract” (Pertegal-Felices et al., 2019) or “charter” (Andrade et al., 2023), a signed document that should signal group members' commitment to a set of principles and procedures to follow. Engineering education researchers have associated a number of beneficial effects with such exercises, the premise being that they “translate implicit assumptions about how members should treat one another into explicit norms and behaviors that can help the group avoid unproductive conflict and create psychological safety” (Feuer & Wolfe, 2023, p. 81).

Unfortunately, it remains unclear whether group norm exercises actually make norm negotiations transparent and inclusive. First, extant research on such exercises has primarily focused on evaluating predefined effects through pre- and post-measurements of group dynamics and group performance (as shown by Borrego et al. in 2013 and confirmed by our literature review). Here, situated interactions between students, from which beneficial effects are assumed to stem, have been paid little direct attention. Second, research projects that do focus on how participation and norms are established interactively have primarily unpacked implicit norm negotiations in on-task interactions (Pattison et al., 2018; Shim & Kim, 2018; Wieselmann et al., 2020). There are scant reports on if and how students' negotiations change when teachers facilitate explicit discussions of group norms and when students, in effect, are more conscious that their exchanges may have tangible consequences for how they will be expected to behave in future interactions.

With this paper, drawing on recordings, interviews, and observations from a project-based undergraduate course, we aim to unveil how students negotiate group norms in group norm exercises, including the different understandings of groupwork that they construct and draw from to facilitate their negotiations. Simultaneously, we wish to problematize the assumption that explicit group norm negotiations are automatically constructive. While evaluations of group norm exercises have mostly reported on positive outcomes (Dahm et al., 2009; Murzi et al., 2020; Pertegal-Felices et al., 2019), students have also experienced such exercises as unhelpful or unnecessary (Andrade et al., 2023; Gatchell et al., 2014; Van Wie et al., 2011) and have expressed needing more guidance on how to conduct their discussions (Avila et al., 2021). This raises the question of what actually happens in group norm exercises and, specifically, how students' negotiations unfold.

To operationalize our research aim, we draw on theories of framing (Goffman, 1974) and framing negotiations (Kaplan, 2008). Framing analysis allows a focus on how understandings and expectations are both dependent on the social context of groupwork as well as continuously negotiated in interaction between participants. Accordingly, we conceptualize group norm exercises as concerned with negotiating joint activity frames for groupwork, which are in turn associated with certain group norms. Before we introduce our theoretical framework, outline our research questions, and describe our empirical approach, we first position our study in relation to previous literature.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

As a background to our empirical investigation, we review research on group norm exercises, group norms, and group norm negotiations, as well as, more broadly, group development and group development interventions.

2.1 Group norm exercises as a recommended but undertheorized tool

While research into engineering education groupwork has shown why and how working in groups can make for impactful learning experiences, it has also illuminated problematic dynamics, putting student learning and well-being at risk. This includes problems such as social loafing (Pieterse & Thompson, 2010), disrespectful behavior (Tonso, 2006), gendered role assignment (Fowler & Su, 2018; Strehl & Fowler, 2019), and students taking an instrumental rather than reflective approach to groupwork (Berge & Danielsson, 2013; Menekse & Chi, 2019).

A common response to these challenges has been to organize group norm exercises, in which students discuss rules of procedure to follow while working together (Avila et al., 2021; Feuer & Wolfe, 2023; Mandal, 2018; Murzi et al., 2020). In group norm exercises, students are given particular areas to address, such as meeting practices, conflict resolution, and how to communicate, and their discussions are directed toward formulating explicit and agreed-upon norms (Aaron et al., 2014; Hunsaker et al., 2011). Usually, these norms are written into a signed document, which students can later refer back to, for instance, to bring up problems for discussion. Sometimes, the process also includes follow-up exercises, where students reflect on their group norms, identify ways to improve their collaboration, and potentially revise their group norm documents (Chang & Brickman, 2018). Group norm exercises constitute a subset of a larger category of group development interventions, that is, learning activities and other support structures specifically designed to preempt group dysfunctioning and improve group learning experiences (Borrego et al., 2013; Lacerenza et al., 2018). Apart from group norm exercises, group development interventions often include a variety of other elements, such as group formation practices (Hanley, 2023; Parker et al., 2019), instruction and exercises focused on productive collaboration strategies (Hurst et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2010), and peer feedback opportunities (Van Wie et al., 2011).

Evaluations of group norm exercises have generally found positive effects on group performance (Dahm et al., 2009; Mathieu & Rapp, 2009) as well as on, for instance, group communication and motivation (Feuer & Wolfe, 2023; Pertegal-Felices et al., 2019). Accordingly, research articles and teaching handbooks often recommend that educators implement group norm exercises when organizing group assignments (Capraro et al., 2013; Jaques & Salmon, 2007). However, there are a few complications. First, effects of group norm exercises are somewhat difficult to untangle, seeing as many studies evaluate them together with a series of additional exercises and support structures (Avila et al., 2021; Murzi et al., 2020; Van Wie et al., 2011). Second, students have in some cases expressed that exercises focused on group development felt like non-helpful busy work (Chang & Brickman, 2018; Gatchell et al., 2014), and that they in practice collaborated based on informally established norms rather than principles documented in group contracts (Andrade et al., 2023). Third, evaluations of group norm exercises, as well as group development interventions more generally, have mainly focused on measuring predefined input and output variables (Borrego et al., 2013), whereas the situated interactions between students—from which beneficial effects are thought to stem—have been awarded little attention. As such, these evaluations say little about what actually happens in group norm exercises, why, and how the potential effects of such activities come about.

2.2 The importance of norm negotiations in developing group norms

In brief, group norms describe both what is normal within a group working on a joint task, such as its established routines, and, importantly, what expectations are established among group members, that is, what the group considers to be desirable behavior (Feldman, 1984; Smith & Louis, 2009). Feldman (1984) argues that group norms make collaboration smoother and more predictable, and help the group to stick together, avoid interpersonal conflicts, and build a common group identity. However, group norms may also create problems, for example, through justifying exclusionary behavior and unfair treatment of specific group members (Tonso, 2006), or through making group activities become focused on only “doing school” (Hutchison & Hammer, 2010).

In engineering education research, the establishment of group norms has primarily been studied in terms of group development (Kaygan, 2023; Quan et al., 2015). Group development can be viewed both as (i) a project that students and teachers sometimes engage in to improve group functioning, and (ii) a process of change and, potentially, improvement in group functioning over time, not necessarily being the product of purposeful effort. Literature on group development suggests that group norms is partly a product of inputs to group processes, including, for instance, individual group member characteristics and group composition (Parker et al., 2019; Pieterse & Thompson, 2010; Sahin, 2011), as well as social context, including, for instance, institutional practices and broader cultural values (Goncher & Johri, 2015; Tonso, 1996, 2006). However, because students are not passive or disinterested when it comes to what is expected of group members, group norms do not develop deterministically from these inputs (Quan et al., 2015). Rather, group norms are continuously processed through group norm negotiations, interactions in which students individually and collectively re-assess their positions, relationships, and expectations given varying situational demands and developments. Regrettably, while Fowler and Su (2018) note that group norm negotiations fundamentally shape group functioning, research on group development in engineering education reveals little about their structure and consequences.

Constituting a partly different strand of literature, investigations of peer interactions in engineering and science education offer some insights into group norm negotiations (Herro et al., 2021; Shim & Kim, 2018; Shim & Krist, 2022; Wieselmann et al., 2020). First, on a basic level, the result of an individual student's attempts to establish or rethink a particular procedure or expectation for groupwork is critically determined by the response received from peers, either supportive or unsupportive (Jordan & McDaniel, 2014). Second, group members are neither equally active nor equally influential when it comes to shaping the direction of the joint work (Engle et al., 2014; Pattison et al., 2018; Wieselmann et al., 2020). Third, processes of negotiating norms and roles are closely connected to negotiating individual and group identity, authority, and recognition (Philip et al., 2018; Shim & Krist, 2022). While these findings indicate some common characteristics of group norm negotiations, most investigations are not undertaken in settings where learning about collaboration is a primary goal of student interactions. Further, extant research has primarily unpacked implicit negotiations in on-task interactions, whereas group norm exercises—our primary focus—are instead structured with the ambition to facilitate explicit and inclusive negotiation of group norms. Students who are primed to learn about collaboration or to find agreement on group norms could potentially exhibit more attentiveness toward each other, as well as more reflection regarding the merits of different approaches. However, explicit negotiations might also prime students to be particularly strategic in trying to get their own perspectives and agendas across. As such, the influence of group norm exercises on group norm negotiations is not yet evident.

3 THEORY: FRAMES, NORMS, AND NEGOTIATIONS

We draw on framing theory (Goffman, 1974; Kaplan, 2008; Tannen, 1993) to conceptualize students' norm negotiations in group norm exercises. Framing theory provides a rich set of concepts describing how communication and social relationships are structured by social context and, at the same time, renewed through social interaction, building on both sociological and linguistic research. In engineering and science education research, framing theory has particularly been used in recent years to investigate how students interactively negotiate participation and identity while working together (Pattison et al., 2020; Shim & Krist, 2022; Wieselmann et al., 2020).

Framing theory highlights that to create order in communication and collaboration, participants in any given situation continuously act on shared definitions of what they are doing, simultaneously reconstructing the said definitions. These shared definitions are usually called activity frames, described by Ramos-Montañez and Pattison (2022) as “emergent understandings or expectations, either implicit or explicit, about the nature and goals of an interaction within a specific situation and context” (p. 336). Activity frames can be seen as products of both past interactions in a given context and meaning-making processes connected to these interactions, which together create certain context-specific understandings and expectations. Because these understandings and expectations are concerned with how to act, activity frames shape current and future interactions. Specifically, activity frames have normative implications because they make certain past, current, and future behaviors and decisions, and not others, particularly intelligible, that is, particularly understandable and legitimate (Butler, 2004). For example, Hutchison and Hammer (2010) describe how students construct alternative activity frames in a science class, understanding classroom activities either as the production of answers for upcoming tests or as making new sense of the natural world. These activity frames come with diverging expectations for how students and teachers should act in class, what roles and responsibilities they should take on, and who counts as knowledgeable. In brief, activity frames come with certain associated norms for interaction.

Framing, as a verb, describes any action contributing to constructing or activating a certain activity frame, that is, any action that actualizes certain understandings and expectations, and not others, concerned with interactions within that context. Several dimensions of social interaction contribute to framing processes, including both verbal and non-verbal aspects, such as turn-taking patterns, participants' interaction with objects or instruments, and, importantly, their choice of words. For instance, Pattison et al. (2020) notice how students can contribute to framing engineering design activities competitively by reacting to having solved a problem with exclamations such as “I did it first!,” while exclamations such as “We did it!” contribute to framing engineering in a more collaborative and supportive manner. Kaplan (2008) uses the term framing repertoire to group together such alternative ways to frame and approach interactions, describing the full array of different activity frames that are drawn on in a certain social setting.

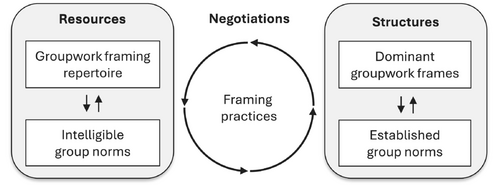

A particularly important point for our study is that activity frames, as well as their associated norms, can locally be more or less dominant or established, but that their status in relation to other activity frames in the framing repertoire is also the subject of continuous negotiation (Kaplan, 2008; Meyer et al., 2016; Snow et al., 1986). Because activity frames have normative implications, participants are not disinterested in how their joint activities are framed. Rather, they are to some extent strategic in how they frame joint activities (Kaplan, 2008; Meyer et al., 2016), mobilizing support for competing action alternatives that are aligned with their own interests. Accordingly, when participants in a specific social context—either incidentally or strategically—frame their joint activities in diverging ways, they engage in frame negotiations, processing the status of activity frames and simultaneously negotiating norms for their interactions (Shim & Kim, 2018). We outline the primary elements of such frame and norm negotiations in Figure 1, situating all elements in a groupwork context. These negotiations can, over time, lead to more lasting changes in how group members understand and approach their interactions. In this way, frame and norm negotiations can contribute to new or transformed group norms. In a group development context, these changes are ideally perceived as beneficial by group members and make the group perform better, although this is not necessarily the case.

In line with framing research concerned with organizing (Kaplan, 2008; Meyer et al., 2016), we view frame and norm negotiations as (i) fueled by a set of framing resources, (ii) shaped by and resulting in certain framing structures, and (iii) manifested in a set of framing practices. In terms of resources, we use the terms groupwork frames and groupwork framing repertoire to denote the array of alternative activity frames that students construct and draw from in their groupwork. This repertoire is associated with a broad set of intelligible group norms, that is, behaviors in and expectations for groupwork that are constructed as understandable but are not necessarily realized or prioritized. In terms of structures, we use the terms dominant groupwork frames and established group norms to denote those frames and norms that are constructed as particularly legitimate and exert more influence over the joint work. Finally, we use the term framing practices to denote repeated interaction sequences that take place between students when they negotiate the status of groupwork frames and their associated group norms, usually initiated when one or several students attempt to frame groupwork as being of a certain nature. As outlined by Kaplan (2008), analyzing framing practices is particularly important for understanding how disagreements among participants as well as tensions between conflicting frames and norms are resolved. As an example of a framing practice, Kaplan describes how extending a certain contested activity frame to include new meanings can serve to bolster or maintain its legitimacy.

4 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

To evaluate whether group norm exercises bring about more transparent and inclusive group norms, our aim is to understand how students negotiate group norms in such exercises. Using framing theory to understand the dynamics of norm negotiations, our analysis is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1.What activity frames are constructed in and through group norm exercises?

RQ2.What group norms are associated with these activity frames?

RQ3.Through what framing practices do students negotiate these alternative frames and norms?

5 MATERIALS AND METHODS

To address our research questions, we conducted an in-depth qualitative study of a set of group norm exercises implemented in a project-based course, using audio-recorded group discussions as our primary data source. The study was designed in line with a sociocultural view of education (Farrell et al., 2021; Lemke, 2001), similar investigations of activity frames and frame negotiations (Kaplan, 2008; Pattison et al., 2020), as well as our theorization of frames and norms as being negotiated in interaction but shaped by more stable relationships and social structures. This meant that we focused largely on getting an in-depth view of students' negotiations in practice, studying their collective talk “in action” (Lofland et al., 2022), while also studying their own understanding of these negotiations. Additionally, we aimed to capture enough of the sociocultural context where these interactions took place, such as the specific academic institution and cohort of students, to put the negotiations in context. Accordingly, we also drew inspiration and procedures from ethnographic research (Delamont, 2012), supplementing our audio-recordings with participant observation in other course activities, student interviews, and continuous member checking.

Before describing our data collection and analysis in more detail, we first describe the empirical setting for the study and our positionality as researchers.

5.1 Research context and group norm exercises

The study was conducted in the context of a project-based undergraduate course on entrepreneurship in the construction sector at a Swedish university of technology (7.5 ECTS). The participants (16 women, 13 men) were all Swedish-speaking students in their third year of a technical bachelor program, having already studied together for 2 years. While not formally awarding engineering degrees, the program heavily featured subjects studied in civil engineering, construction engineering, and industrial engineering and management (which is an engineering degree in Sweden). Over 10 weeks, the students worked on a project assignment in groups of four or five, formed by the teachers. The project involved generating, developing, and pitching new business ideas in the construction industry by iteratively seeking feedback from potential customers and industry practitioners. The course design, organized around an intensive project with explicit learning outcomes focused on developing collaborative skills, made it a suitable setting for studying how teachers can support group development in an engineering education context.

In conjunction with the projects, a sequence of group norm exercises was implemented, centered on working with a team charter (Aaron et al., 2014; Hillier & Dunn-Jensen, 2013; Hunsaker et al., 2011; Mathieu & Rapp, 2009). At three points during the projects, students worked on their team charters in class, forming a group development intervention that is presented in Figure 2 (including descriptions of data collected in relation to each activity). The first activity involved constructing an initial charter by sharing group members' previous groupwork experiences, discussing what principles should govern their groupwork, as well as documenting and signing their agreed-upon charter document. Midway through the project, the students evaluated their groupwork, revisited their agreed-upon group norms, and revised their team charters based on the experience so far. Finally, at the end of the project, the students reflected on how their groups had developed over time, to draw out insights about groupwork and group development.

5.2 Positionality

The study was conducted as part of a larger ethnographic research project undertaken by the first author (O.H.S.) for his doctoral dissertation work. The larger project included extensive observations, interviews, and document analysis conducted over 3 years, with a broad focus on understanding learning processes within this particular learning environment. The first author was also one of the main teachers in the course, being tangibly invested in the success of the students and the continuous development of the course design (see discussion of potential challenges with this setup below). Initially, the study was motivated by a practical interest in improving groupwork experiences in this educational setting. However, designing the group development intervention investigated here raised more fundamental questions regarding the dynamics of group norm exercises.

The full author team comprised three Swedish-speaking STEM education researchers, with educational backgrounds that combine natural science and engineering with social and educational science. We all usually adopt sociocultural perspectives in our research, being interested in engineering learning as an interactional and situated achievement. Through working together, we have developed a joint interest in critical educational perspectives, focusing on how certain assumptions, ideologies, identities, and social norms are supported and/or subjugated in engineering education. This drew our attention to social dynamics in the group norm exercises and, more specifically, potentially problematic social dynamics.

5.3 Data collection

At the start of the course, students were informed about the research project, that participation was voluntary, that the difference between participation and non-participation mainly was that their group interactions would be recorded and the information they supplied would be analyzed for research purposes, and that they could choose to opt out at any point. As the main researcher was also one of their teachers, extra care was taken to clarify the relationship between information collected in the course for grading purposes—through assignments—and the extra data collection conducted for research purposes. Interviews with students were conducted after grading was finished, and, in general, the role of teacher and researcher was separated between different occasions—no data was collected in teaching situations.

To investigate students' group norm negotiations, all three group norm exercises were audio-recorded. We chose audio recordings over video recordings because our main focus was on students' talk and because we wanted to minimize the intrusiveness of the data collection (Swann, 1994). To obtain a visual sense of the discussions and how students physically interacted with each other and the team charter template, the first author observed the exercises and documented observations in field notes. All seven student groups were recorded during the first and second group norm exercise. After the revision discussion, three of the seven groups that exhibited differing levels and different types of group conflict were purposively sampled to take part in retrospective focus group interviews, conducted by the first author. The final group norm exercise of these three groups (here referred to as Team Armadillo, Team Porcupine, and Team Pangolin) and their focus group interviews were also audio-recorded, resulting in approximately 16 h of recorded student group discussions, used for in-depth analysis of group norm negotiations.

During the retrospective focus group interviews, the students were asked to describe and discuss (i) their experiences of the group norm exercises, (ii) whether and in what sense they believed the exercises had affected the development of their groups, and (iii) what they had learned from working with group development. Subsequently, audio excerpts from the group norm exercises were played back and students were probed to reflect upon the nature and consequences of their conversations. Some emerging interpretations from the ongoing analysis were presented and discussed with the students to elicit further input.

Although transcripts from the audio-recorded exercises and interviews constituted the most important material in our data analysis, we used a number of additional data sources as supplementary material to aid us in interpreting the nature and consequences of students' negotiations. Three sets of open and closed survey questions were administered at the beginning (N = 18), middle (N = 26), and end of the intervention (N = 21), probing students' previous experiences of groupwork, their perceptions of current group functioning, as well as experiences and takeaways from the group norm exercises. Additionally, the first author followed up via email and phone with three individual students after the focus group interviews to ask them in more detail about their individual experiences, which they hinted at in the group interviews but seemed hesitant to share in full with their groups—primarily experiences of problems with the group dynamic. All data collection and following analysis was done in Swedish, and extracts included in the paper were subsequently translated into English in a translation as closely as possible preserving the meaning of utterances.

5.4 Analysis

Following the interpretative epistemology of ethnography and framing theory, in our analysis we aimed to form a robust and meaningful interpretation of the social processes represented in our empirical material. We followed an abductive logic (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012), moving between (i) openly coding and interpreting our data and (ii) testing out a gradually refined set of theoretical concepts inspired by previous work. The coding process and handling of data were driven by the first author, continuously discussing tentative interpretations with the co-authors. In general, the process involved iterative development and testing of alternative hypotheses and descriptions and a continuous evaluation of the validity of tentative findings through re-reading the empirical material and looking for contradictory observations. As a process support, tentative analyses were documented in consecutive analytical memos shared among the authors (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Through these efforts, we gradually built an empirically and theoretically informed interpretation of negotiations within the group norm exercises.

The final stages of our analysis process included two phases of more clearly theory-driven analysis. First, we identified the groupwork framing repertoire available to students by categorizing the different ways they constructed and approached the groupwork. To this end, the first author extracted utterances from the material where students talked or wrote about their groupwork as a particular type of activity. Group behaviors and interactions between students that aligned or disaligned with their descriptions of groupwork were also noted. These utterances and interactions were analyzed using procedures for theoretical thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), coding, recoding, and classifying the material with the help of NVIVO software. In this analysis, the audio recordings of group norm exercises and retrospective interviews served as the primary material, because students here both enacted activity frames and spoke about their understanding of and approach to groupwork in more detail. Further, the survey material was used for triangulation, making sure that we did not omit groupwork frames, group norms, or student experiences, which were common among groups that did not participate in retrospective interviews.

Second, we identified framing practices through which students negotiated the framing repertoire, categorizing recurring interaction sequences between students with consequence for the status and relationships of identified frames and norms. Here, the first author extracted sequences of verbal interactions from the audio-recorded group norm exercises where students negotiated the status of two or more alternative activity frames, including chains of such interactions unfolding over time where similar topics and negotiations were revisited. For each such interaction and chain of interactions, we identified the competing framing attempts made by students, whether these bids for understanding the joint work were taken up by other students, what actions and decisions were at stake, and whether and how potential disagreements were resolved.

In this final analysis process, to capture the complexity of our findings, we needed to make a distinction between two types of negotiations, including two categories of frames and associated norms at different levels of specificity. A subset of the frames, norms, and negotiations we identified concerned how to approach groupwork in general, including all aspects of the project. We retain the terms groupwork frames and group norms to describe frames and norms in this category. A second subset of frames, norms and negotiations, however, more specifically concerned how to work with group development and the exercises themselves. We use the terms group development frames and group development norms to describe this second category. Here, group development frames denote the different understandings of group development that students constructed and drew from in the group norm exercises. The term group development norms, in turn, describes expectations for what groups and group members can and should do to improve groupwork. Just like groupwork frames and group norms, some group development frames and group development norms appeared as more established than others.

6 FINDINGS

The findings are presented in three sections below. First, we describe the different groupwork frames students drew on, serving as reference points for their negotiations but also sources for disagreements. Second, we detail the structure of their negotiations, including framing practices employed to resolve or move on from disagreements. Third, we describe how students negotiated their engagement in the group norm exercises themselves, including how the group development frames and group development norms that were established in turn shaped the structure of their group norm negotiations. We illustrate this relationship between negotiations on the level of group norms and on the level of group development norms in Figure 3.

6.1 Groupwork frames, groupwork norms, and a salient tension

When discussing the group norms they wanted to establish, students alternatively framed their groupwork as being between (i) friends, (ii) students, and (iii) colleagues. These alternative groupwork frames are presented in Table 1, including group norms associated with each frame.

| Groupwork frame | Description | Example quotes | Associated group norms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friendship | Approaching interactions within the projects as being between friends. | “When working with friends, you can be open about things. You can tell each other almost anything” (Anton, Team Armadillo, Exercise 3). “I remembered a very important point: We need to enjoy ourselves!” (Seb, Team Armadillo, Exercise 1). |

Group members should be supportive, open, and accept each other as they are, should not talk behind each other's backs, and should enjoy themselves. |

| Studenthood | Approaching interactions within the project as being between students | “If we are going to succeed in doing this pitch and getting our grades, I think we need some more input” (Ida, Team Armadillo, Exercise 2). “Perhaps we should alternate who chairs the meetings? It might be good to practice that role” (Sara, Team Porcupine, Exercise 1). |

Group members should try out new things in order to understand the methods and problems presented. Group members should finish assignments and get their grades. |

| Work | Approaching interactions within the project as being between professional colleagues. | “It can be easier to be professional, to do it like a job, if you don't know each other too well” (Ida, Team Armadillo, Exercise 3). “In a job, you often need to adapt to a group in order for things to work” (Jessica, Team Pangolin, Interview). |

Group members should take responsibility, be productive, efficient, serious, ambitious, creative, and somewhat detached. |

Among these alternative activity frames, friendship constituted a particularly influential frame. The students often presented themselves as friends, constructing their relationships as being “close,” “positive,” “equal,” and not “formal.” Commenting on the nature of social relationships in this context, Mikael of Team Porcupine explained in an interview that for many students, the program constituted their primary social network and that many “hang out all the time.” In line with this framing, group members encouraged each other to “have fun together,” “let one's guard down,” and not to “talk behind each other's backs” while working together. In contrast, when the collaboration was, more sporadically, framed as part of “work,” or as similar to a “job,” group members instead usually encouraged each other to be “professional,” “productive,” “serious,” and “efficient.”

The tension between working together in a formal professional or informal friendly manner was one common source of disagreement between students, manifesting in both practical and explicit negotiations. For example, in Team Armadillo, Ida frequently tried to establish somewhat more formal relationships. Because the group often digressed, making unrelated jokes or discussing weekend plans, Ida tried to bring conversations back to matters concerning the groupwork. When students discussed the quality of their project hand-ins, Ida more often than others pointed out improvements they could make, while Anton in particular indicated that they should settle for good enough. After already having had a few disagreements regarding the level of formality, as shown in Excerpt 1, Ida proposed a compromise to coordinate their expectations.

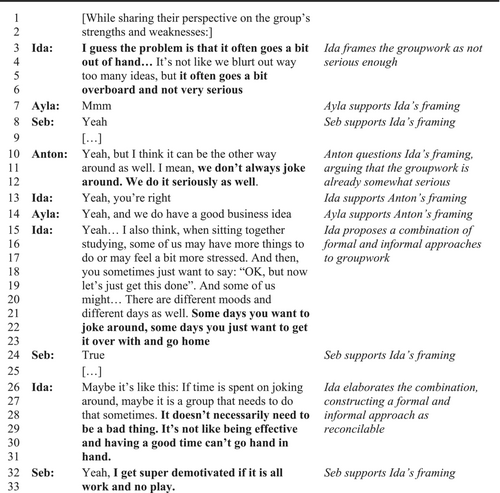

EXCERPT 1. Team Armadillo coordinating groupwork frames and associated expectations, from Exercise 2. Particularly significant utterances are marked in bold. In the right column, an interpretation of each utterance is provided, in terms of framing attempts and how these are processed. In the transcript, … denotes a pause in speech and […] denotes an editorial omission. The same structure is used for the following excerpts.

In the exchange described in Excerpt 1, Team Armadillo temporarily resolved their disagreement through recognizing that there may be merit to both professionalism and friendship in groupwork (“getting it done,” line 19, and staying “motivated,” line 32). While Team Armadillo did not agree on exactly how to implement a compromise between being efficient and having a good time, and while they kept having certain disagreements concerned with the level of formality, they here started to construct a common frame for their groupwork where multiple positions were recognized as legitimate.

6.2 Negotiating group norms through accepting, rejecting, coordinating, and transforming activity frames

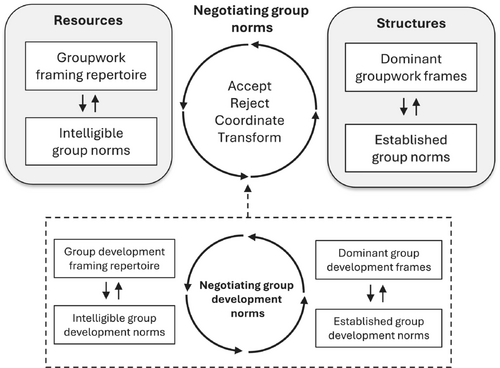

Following a framing attempt from an individual group member, such as the one initiated by Ida in Excerpt 1, the students' negotiations unfolded in a number of different sequences. These are illustrated in Figure 4. Before outlining the central components of these sequences, namely the framing practices, we make a general observation that an overwhelming majority of negotiation sequences did not end with explicit and documented decisions. For the most part, the students started to create their team charter only toward the end of the session, in a process which Seb of Team Armadillo in an interview characterized as just writing down what they remembered from their discussion. Instead, students' interactions were mostly focused on negotiating a more general framing for their groupwork, and then moving on to new topics of discussion.

Negotiation sequences generally progressed through accepting, rejecting, coordinating, or transforming the proposed frames and norms. Frame acceptance, quite simply, occurred when other group members expressed support for a statement or suggestion made regarding the nature of groupwork in general or regarding their groups' own norms. Particularly in the first group norm exercise, when group norms had not yet been put to test, students' interactions were clearly dominated by—at least overtly—agreeing with each other's suggestions and premises. For most groups, this general interaction pattern was maintained in subsequent group norm exercises.

Frame coordination, in turn, was one of three responses when disagreements arose regarding how to approach groupwork. As has already been illustrated in Excerpt 1, frame coordination involved constructing multiple alternative approaches and expectations as having merit and proposing combinations or compromises to overcome tensions. In the case of Team Armadillo, frame coordination was achieved by Ida explicitly constructing the value of different approaches as situational, varying between persons and groups as well as between different days (lines 15–23).

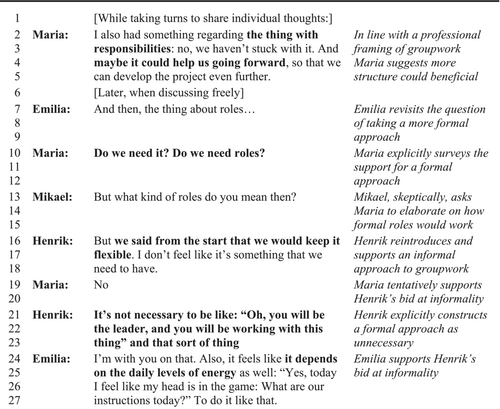

Another common practice was frame rejection. Here, disagreements were resolved by constructing one frame or norm as inherently more important or legitimate than the others, rejecting other opinions and alternatives as irrelevant. For example, while Team Porcupine, like Team Armadillo, had fairly relaxed conversations and frequently framed their collaboration as being informal and friendly, some disagreements occurred in relation to Maria's repeated suggestion that the group could potentially benefit from taking a more structured approach. In Excerpt 2, Henrik together with Emelie contest and reject one of Maria's framing attempts, explicitly constructing a more structured approach as being unnecessary.

Excerpt 2 illustrates how frame rejection served to shut down framing attempts, primarily framing attempts that challenged the group's established norms, reaffirming frames that were more aligned with established norms. In Excerpt 2, frame rejection is achieved by questioning how an alternative approach would even work (line 14), what its value would be (lines 17–18), and re-emphasizing the merit of current approaches (lines 24–27). Henrik even provides an imitation of how silly Maria's alternative suggestion sounds (line 21–23). As compared to Team Armadillo's frame coordination in Excerpt 1 where multiple understandings and positions were acknowledged, Team Porcupine here puts into question both Maria's status in the group and the overall legitimacy of taking a more structured approach to the groupwork. In effect, this frame rejection discourages further bids at reframing the groupwork.

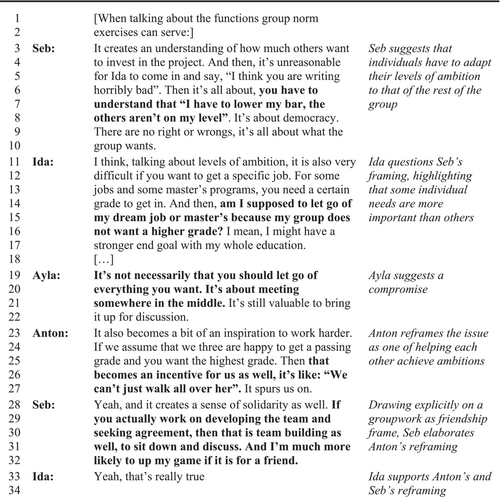

In a few instances, rather than accepting, rejecting, or coordinating their expectations, students instead engaged in transforming frames and norms. Here, disagreements were settled through rethinking and reshaping one or several groupwork frames, redefining their implications for group norms. For example, the negotiations in Team Armadillo regarding how formal groupwork should be (as exemplified in Excerpt 1) necessitated continued processing. In Excerpt 3, in response to a disagreement between Seb and Ida regarding whether individual group members should always adapt their levels of ambition to the group, Ayla first proposes a compromise, while Anton and Seb go on to reshape the implications of what it means to work together as friends.

In Excerpt 3, we see an example of how groupwork frames can be transformed to be associated with partly new group norms, and how such a transformation can facilitate an alternative avenue for resolving disagreements. In Excerpt 3, new implications of working together as friends are introduced, emphasizing that friends can indeed “up their game” (lines 31–32) and get a whole lot done, to help each other reach their ambitions. Instead of downplaying the value of discipline or settling for a compromise, the group here resolves the issue by complexifying the friendship groupwork frame, adding to it a language of responsibility and accountability.

These different ways of resolving disagreements directly shaped the consequence of students' norm negotiations, especially in terms of allowing the groups to maintain and draw on a more narrow or more diverse constellation of groupwork frames. Frame rejection served to bolster the status of specific frames and norms, however doing so at the expense of alternative understandings and approaches being constructed as unnecessary or even useless. Frame coordination served to maintain the legitimacy of multiple frames, balancing their influence over the joint work. Finally, frame transformation served to more fully overcome tensions between frames, by redefining their normative implications. Through frame transformation, rather than just rejecting or compromising between alternative approaches, the group norm exercises served to widen students' joint understanding of what different approaches to groupwork could entail.

6.3 Negotiating group development frames and group development norms

As we have already noted, we observed that for this particular cohort of students, certain groupwork frames and framing practices were more common than others. In short, the exercises were characterized by discussing rather than making decisions, by agreeing rather than disagreeing or problematizing, and by resolving disagreements that did arise through rejection or compromise rather than through transforming groupwork frames. In trying to understand why and how this particular dynamic was established, we found that the structure of students' norm negotiations, in turn, was influenced by the second type of frames and norms we had identified, concerned with how to work with group development and with the group norm exercises themselves. Specifically, the students alternatively approached the activities as (i) a meaningless assignment, (ii) a team-building experience, (iii) the creation of a social contract, and (iv) an opportunity for group evaluation and improvement. These alternative frames are presented in Table 2, focusing on direct normative implications for how to engage in the exercises.

| Group development frames | Description | Example quotes from students | Associated norms for the exercises |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meaningless assignment | Approaching the group norm exercises as something that needs to be over and done with. | “Some things you do just because someone has told you to do it. You do it even though you feel like ‘Well, I don't see any point in it’. But it needs to be done, so you do it” (Jessica, Team Pangolin, Interview). | Group members should move on quickly and talk about things that are more important. |

| Team building | Approaching the group norm exercises as an opportunity to get to know each other and create a sense of belonging. | “When working with people of different ages, experiences, and backgrounds, then it is good to get to know a bit more about each other” (Johanna, Team Pangolin, Interview). | Group members should talk about who they are in a group, share their own thoughts and listen attentively. |

| Social contract | Approaching the group norm exercises as clarifying and documenting group norms. | “Just imagine if your group would have lots of conflicts. Then you would have written down ‘We are going to work like this’, and then at least you have something to fall back on” (Ayla, Team Armadillo, Exercise 2). | Group members should talk about their individual expectations, negotiate, and agree on principles. |

| Group evaluation | Approaching the group norm exercises as an opportunity to evaluate group functioning. | “If you don't sit down and think about ‘Well, this is how we have done it, how should we do it in the future?’, then you will never change” (Alex, Team Pangolin, Exercise 3). | Group members should talk about the group's way of working, exploring, and reflecting collaboratively. |

Among these alternative frames, it was especially common for students to talk about the group norm exercises in terms of team building, emphasizing how such activities may contribute to a “nice atmosphere,” “a sense of belonging,” a good “social environment” and group members who “know each other well.” In line with this dominant frame, group members encouraged each other to “share” and talk about “personal” things, such as their “strengths and weaknesses” and “what you need” in a group. This framing of the activities is mainly aligned with engaging in frame acceptance, listening to each other's ideas and input, and not with disagreeing or problematizing. Framing the group norm exercises as a meaningless assignment or as serving the purpose of creating a social contract was also common. Here, whereas the meaningless assignment frame was associated with moving on quickly to talk about more important things, the social contract frame aligned with a wider set of framing practices, including acceptance, disagreement followed by rejection, as well as disagreement followed by coordination and compromise. In contrast, when the activities were, more seldom, framed as an opportunity for group evaluation and “a tool for improving the work,” members were, instead, encouraged to focus on the group's established way of working, bringing up reflections about previous performances so that problems can “come to the surface.” Out of these four alternative group development frames, the group evaluation frame alone directly aligned with frame transformation as a way to resolve disagreements, facilitating a more fundamental rethinking of established group norms.

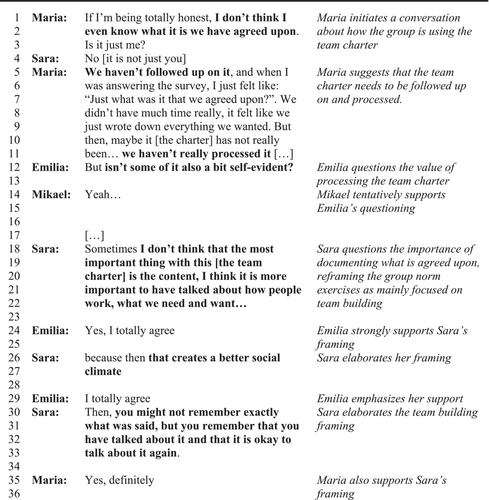

As compared to the negotiation of group norms, the negotiation of group development norms was often less visible, only seldom being the topic of explicit discussion. Some practical negotiations were apparent when certain students steered the conversation away from group norms, for instance, deeming project content a more meaningful topic of discussion, while others tried to refocus the conversation on group functioning. Some students also tried to explicitly renegotiate their approach to group development. For example, while Team Porcupine usually framed the group norm exercises either as being somewhat meaningless or as potentially facilitating team building, Maria sometimes suggested that they take a more structured and critical approach. However, as shown in Excerpt 4, this was rejected in favor of again framing the exercises as mainly involving team building.

Excerpt 4 here illustrates that although some students, such as Maria in Team Porcupine and Ida in Team Armadillo, tried to use the group norm exercises to properly rethink and renegotiate their group norms, it was difficult to establish this as being the goal of their interactions. Responding to Maria's suggestion (lines 5–11) that the group needs to work more actively with “processing” the norms they agreed upon, Emilia (line 12), in contrast, frames this as somewhat meaningless, given that it is fairly “self-evident” how group members should behave. Finally, Sara (lines 18–34) frames their conversation in terms of team building, focused on talking about what they as individuals “need and want,” rather than group functioning. While Sara guides the group to construct the intervention as potentially worthwhile, this framing still means that the alternative of more actively interrogating their established group norms is rejected.

7 DISCUSSION

The purpose of group norm exercises is to facilitate group development, preempt group dysfunctioning, and—specifically—to help students to develop transparent norms every group member can agree on (Andrade et al., 2023). This can be seen as a relevant response to research indicating that students usually negotiate group norms only implicitly, with interaction patterns that give group members unequal influence over norms (Wieselmann et al., 2020). Investigating group norm exercises in a project-based course, we found that students' explicit norm negotiations involved a set of framing practices through which students were able to coordinate expectations, overcome differences, build a common group identity, and transform their understandings of different approaches to groupwork. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms of group norm exercises, detailing through what types of situated interactions such exercises may benefit group functioning (Avila et al., 2021; Murzi et al., 2020; Pertegal-Felices et al., 2019).

However, our findings also indicate that making norm negotiations explicit does not guarantee that all students will have equal influence over group norms. Specifically, locally established norms for how to engage in groupwork and in group norm exercises may not be particularly negotiable, limiting what students may achieve in their conversations. Group norm exercises could potentially even lead to these norms becoming less, rather than more, open for deliberation, seeing as such exercises may entail explicitly constructing established norms as being evident, self-explanatory, or common sense (Philip et al., 2018). Here, students holding alternative expectations for groupwork may face a double challenge: Before attempting the difficult task of renegotiating group norms, they first may need to renegotiate group development norms, changing the focus of group norm conversations from reaffirming an established group identity to instead focus on potential problems. In our case, one student (in a follow-up interview) explicitly reported that this led him to gradually disengage from the group norm exercises, which in turn meant that his group created an official and signed norm document that in practice did not reflect the will of the full group. We agree with Feuer and Wolfe (2023) that such a dynamic may be particularly problematic for the participation and well-being of students who do not enjoy the same social status as others, for instance, students from demographic groups that are underrepresented in engineering education.

7.1 Theoretical and methodological implications

Our findings suggest that both the dynamics and the consequences of group norm exercises may be more complex and contextually contingent than what has been assumed in much previous work. Some previous research has indeed shown that group functioning may be hampered if group norm documents exhibit problematic characteristics, for instance, not being detailed enough (Mathieu & Rapp, 2009), or being too focused on setting out seemingly self-explanatory group norms (e.g., showing respect and taking responsibility) and punishment for rule-breaking, instead of coordinating multiple legitimate viewpoints that otherwise could come into conflict (Feuer & Wolfe, 2023; Sverdrup & Schei, 2015). However, we here feel the need to point out that the process of creating a group norm document is more likely to have consequences for group development as compared to the document itself, particularly because group norm documents do not necessarily reflect group norm conversations, and because students seldom refer back to their norm documents after having created them (Chang & Brickman, 2018). As such, a focus on the qualities of interactions rather than the qualities of documents is long overdue in research on group norm exercises.

In relation to the broader literature on group development in engineering education, the study contributes new insights into how students develop group norms. A key finding is that group norm negotiations are shaped by norms and understandings concerned with group development, that is, what is locally understood as group “improvements,” to what extent such improvements are conceived as important, and, if so, how they can and should be reached. Such group development norms may have tangible consequences for students' group development processes, particularly in educational contexts where students are explicitly tasked with trying to develop well-functioning groups. While more stable factors such as member characteristics, group composition, and broader cultural values can still be thought to set the general conditions for how student groups develop while working together (Mathieu et al., 2008), group development norms may shape the manner in which students navigate and negotiate these conditions.

Our most important methodological implications concern how to evaluate group development interventions in engineering education, including not only group norm exercises, but also, for instance, group formation practices and exercises focused on evaluating group member performance. While previous research has observed groupwork up-close and over time (Goncher & Johri, 2015; Kaygan, 2023), most research on group development interventions—perhaps unsurprisingly—follow an intervention research logic, evaluating activities and support structures mainly through quantitative pre- and post-measures of group dynamics and group performance (Aaron et al., 2014; Murzi et al., 2020; Pertegal-Felices et al., 2019). We believe this to be an important research approach, especially when isolating design elements and properly controlling for confounding variables. However, it also has multiple limitations. First, such evaluations shine limited light on how and why certain instructional elements bring about certain effects (Astbury & Leeuw, 2010), and what unexpected side effects they may have (Biesta, 2007). Second, group development interventions, like educational interventions in general, are unlikely to unfold uniformly and have the same consequences regardless of social context (Stöhr & Adawi, 2018). Here, we believe that our research approach, similar to the approach taken by Quan et al. (2015), is especially well positioned to generate new insights about group development interventions, more directly taking process and context into account by performing direct observation of social interactions within such interventions.

7.2 Implications for practice

How can teachers better support the development of productive and inclusive group norms in engineering groupwork? In our case, although a structured process for developing group norms was offered, we believe that too much responsibility was put on students to drive this process, with inadequate instruction on how to approach each step. First, the intervention design did not properly recognize that these students, like many others, came to groupwork with a common history, with established relationships, and with collectively maintained expectations for how to approach groupwork. Instead of teaching as if norm development is only about coordinating individual expectations, a preferable approach would have been to also supply prompts for students to critically interrogate norms about groupwork that they have been socialized into. We believe that this would serve as a valuable alternative to current practices of letting students undertake psychology-inspired, but controversial, personality tests and learning style inventories to inform their discussions of group norms (Dahm et al., 2009; Knobbs & Grayson, 2012; Michalaka & Golub, 2016). Relevant norms to highlight depend on the local context. For example, in the case of this class, it could have been valuable to prompt students to discuss potential challenges of approaching groupwork in an informal manner, highlighting, for instance, potential consequences for students who are not as socially connected or students who want to focus on performing. Second, to avoid that group norm conversations mainly result in reinforcing dominant social norms, teachers should ideally prepare students by discussing the nature of implicit and explicit norms and norm negotiations, by modeling constructive negotiation strategies, and by directly observing and giving feedback on how students negotiate (Bowen et al., 2022). A concrete preparation could be to analyze real or fictive excerpts from group norm negotiations together with students, for instance, illustrating frame coordination, frame transformation, and frame rejection, highlighting how the process is influenced by earlier experiences as well as students' relationships and social status.

Our findings also suggest that teachers and program coordinators aiming to develop collaborative skills among students should be conscious of the group development norms they contribute to in both curriculum design and in interactions with students. Several students in our study reported that their expectations were shaped by previous experiences of having created group norm documents, being organized into groups on the basis of unknown criteria, and by teachers generally promising but not delivering adequate support for group development. From this, many had taken away a justifiable feeling that pursuing group development in educational settings usually did not amount to much. Beyond providing students with better conditions for group development, we believe another important strategy to address these concerns would be for teachers to frame group development interventions in a different way than they are usually framed and evaluated in literature, namely as opportunities to learn about group development rather than as instruments that will necessarily bring about group development. Focusing on learning serves a dual purpose: First, students can become progressively more apt at working with group development, which in itself constitutes a valuable professional skill. Second, experiences of group dysfunctioning can ideally become learning opportunities rather than learning disruptions. Importantly, to deliver on such an approach, assessment practices should give students opportunity to demonstrate their insights into group development and should not punish student groups that experience interpersonal problems (Bernhard et al., 2016). One way of doing this is to shift both learning goals and assessment toward group learning, for example, incorporating assignments in which students are to reflect on group development. Of course, this may involve a reprioritization of syllabi, as well as of instructors' and students' time, which in practice needs to be considered in relation to other goals.

7.3 Limitations and future work

We have contributed with what we believe is a first investigation of explicit group norm negotiations in engineering education. However, our investigation is limited to one specific educational context, influenced, for instance, by local ideas about groupwork and group development, as well as a specific instructional design. Overall, all frames, norms, and framing practices outlined in our study may not be completely transferable. For instance, friendship as a frame and norm may not necessarily be as salient in other educational settings. However, we believe that frames, norms, and framing practices are important in group norm negotiations also in other settings and that the relationships we have described between these types of elements are more transferable.

Furthermore, our research design has certain limitations. First, because we were primarily interested in understanding the dynamics of explicit group norm negotiations, we did not record project interactions outside of the group norm exercises. Starting from our material, we believe we have gained an understanding of students' group norms, as well as how they processed these norms, particularly because we recorded students discussing their groupwork at several stages of the project, because students eventually started to voice disagreements regarding their groupwork, and because we were able to form a coherent interpretation using the accounts of students who were both satisfied and dissatisfied with their group norms. Still, also analyzing group interactions outside of the group norm exercises could have yielded an even better understanding of the process. Second, the fact that the main researcher was also one of the teachers in the course involved a certain risk of influencing the findings, when it comes to what students are willing to share in interviews, but also when it comes to the interpretation of the data. The risk of over-familiarity with the students and the course has been mitigated by the continued scrutiny of interpretations by the co-authors, but it is possible that a different researcher positionality would have led to uncovering further dynamics, for instance, concerning how input from the teachers framed and influenced the groupwork.

In light of our findings, we deem two avenues of future research especially fruitful. First, to better understand what is needed to ensure critical and equitable negotiation of group norms, we believe future work should investigate how norm negotiations change when students are instructed on explicit negotiation strategies and provided with prompts to scrutinize the groupwork norms that are salient in their educational setting. Here, apart from observational studies of processual dynamics, comparative studies measuring the relative effects of different intervention designs may indeed also be useful. Second, we believe that research identifying group development norms in other contexts may yield new insights into how and why student groups change and improve as they work together, as well as why they may not change and improve, particularly in educational settings where both students and teachers are expected to take more responsibility for group functioning. Research projects done in conjunction with program development could investigate what understandings of and attitudes toward group development could be fostered among students and teachers through building progression in group development interventions across courses and across program stages.

8 CONCLUSIONS

As engineering education institutions increasingly emphasize collaborative learning, it becomes increasingly important for engineering educators to understand how groupwork experiences unfold, how group norms are formed, and what strategies and tools they can use to support student groups. This study has contributed by investigating how students negotiate group norms in group norm exercises, including the understandings of groupwork and group development they draw on to facilitate their negotiations. By analyzing social interactions in group norm exercises, we were able to evaluate whether making group norm negotiations more explicit would also make them reflective and equitable. We found that group norm exercises can indeed facilitate constructive negotiations in which students can overcome differences and coordinate multiple legitimate approaches to groupwork. We also found, however, that group norm exercises can lead to students being actively discouraged from questioning established group norms. We conclude that if we want to foster transparent and inclusive norms in engineering groupwork, teachers need to better prepare students for group norm negotiations. Ultimately, if engineering students do not get the time and opportunity to critically interrogate groupwork norms, graduates might feel that norms in the engineering workplace is something they have neither control over nor responsibility for.

Biographies

Oskar Hagvall Svensson is a Researcher of higher education pedagogy at University of Gothenburg, School of Business, Economics, and Law, Vasagatan 1, SE 411 24, Göteborg, Sweden; [email protected].

Anders Johansson is a Senior Lecturer in engineering education research at Chalmers University of Technology, Hörsalsvägen 2, SE 412 96, Göteborg, Sweden; [email protected].

Tom Adawi is a Professor of engineering education research at Chalmers University of Technology, Hörsalsvägen 2, SE 412 96, Göteborg, Sweden; [email protected].