Elephant conservation in India: Striking a balance between coexistence and conflicts

Editor-in-Cheif & Handling editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

Abstract

enIn the human-dominated epoch of the Anthropocene, nations worldwide are trying to adopt a variety of strategies for biodiversity conservation, including flagship-based approaches. The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) plays a pivotal role as a flagship species in India's biodiversity conservation efforts, particularly within its tropical forest ecosystems. As the country harboring the largest Asian elephant population among the 13 range countries, India's conservation strategies offer valuable insights for other range countries. This study elucidates India's elephant conservation paradigm by outlining a historical account of elephant conservation in the country and examining the current administrative and legal frameworks. These are instrumental in implementing strategies aimed at maintaining sustainable elephant populations. Our study also analyzes trends in elephant populations and negative human–elephant interactions, drawing upon data from a centralized government database. Our findings indicate that the elephant population in India is reasonably stable, estimated at between 25,000 and 30,000 individuals. This figure constitutes nearly two-thirds of the global Asian elephant population. India's elephant population occupies ~163,000 km2 of diverse habitats, comprising 5% of the country's land area, with their distribution spread across the northern, northeastern, east-central, and southern regions. This distribution has shown fluxes, particularly in the east-central region, where large-scale elephant dispersals have been observed. Between 2009 and 2020, human–elephant conflicts in India have resulted in an average annual loss of 450 (±63.7) human lives. During the same period, the central and state governments paid an average of US$ 4.79 million (±1.97) annually as ex gratia for property losses. Recognizing the critical nature of these conflicts, India has implemented various measures to manage this pressing conservation challenge. Overall, sustaining the world's largest extant population of wild elephants in the midst of India's human-dominated landscapes is enabled by a robust institutional policy and legal framework dedicated to conservation. This commitment is further reinforced by strong political will and a deep-rooted cultural affinity towards elephants and nature, which fosters a higher degree of tolerance and support for conservation efforts.

摘要

zh在人类主导的人类世时代,世界各国正试图采取各种策略,包括基于旗舰物种来进行生物多样性保护。亚洲象(Elephas maximus)在印度生物多样性保护工作中扮演着重要的旗舰物种角色,特别是在其热带森林生态系统中。作为 13 个亚洲象分布国中亚洲象种群数量最多的国家,印度在亚洲象保护范例方面有着重要的经验,其他分布国也能从中受益。在此,我们通过概述印度保护亚洲象的历史以及当前实施旨在维持可持续亚洲象种群的策略的行政和法律框架,来阐明印度的亚洲象保护模式。我们还根据中央政府数据库,介绍了亚洲象种群和人象负面互动的趋势。研究表明,印度的亚洲象数量稳定在25,000至30,000头之间,占全球亚洲象数量的近三分之二。印度的亚洲象种群分布在北部、东北部、中东部和南部的约16.3万平方公里的多样化栖息地中,占其总陆地面积的5%。亚洲象的分布呈现出波动性,尤其是在中东部地区,观察到了大规模的亚洲象散布现象。2009-2020 年间,平均每年有450人(± 63.7)死于人象冲突。同期,中央政府和邦政府平均支付了479万美元(± 197)的财产损失补偿金。印度认识到负面的人象互动是亚洲象保护面临的紧迫挑战,并采取了一系列措施加以管理。总体而言,印度能够在人类主导的景观中维持现存最大的野生亚洲象种群,得益于其强大的保护制度、政策和法律框架以及政治意愿,而对亚洲象和大自然的深厚文化情感则进一步巩固了这种政治意愿,并转化为更好的容忍度。【审阅谷昊】

Plain language summary

enAsian elephants (Elephas maximus) are highly endangered, occurring as isolated, fragmented populations across 13 range countries. Among the range countries, India is home to more than 60% of the extant wild elephant population, with 25,000–30,000 elephants spread over 1,63,000 km2 of diverse landscapes. Available data on population trends suggests India's elephant population has been reasonably stable. However, these elephants often live close to human-dominated areas, leading to frequent human–wildlife conflicts, affecting both human livelihoods and elephant conservation. To tackle this issue, India has been advancing a variety of mitigation strategies to reduce these conflicts. Despite these challenges, India's robust legislation and policy framework, backed by strong political commitment, have been vital in current elephant conservation practices. This study discusses key contemporary challenges facing elephant conservation in India and ways to manage them with the objective of effectively sustaining viable elephant populations.

Practitioner points

en

-

India harbors the world's largest extant population of the endangered Asian elephant (Elephas maximus).

-

Major challenges to elephant conservation in India include human–elephant conflict and the impacts of infrastructure development.

-

The country has developed and implemented institutional, policy, and legal reforms, which, combined with public support for wildlife conservation and political backing, will enable elephant conservation in India.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human-driven species extinctions are a hallmark of the Anthropocene epoch we live in (Dirzo et al., 2014). Large-bodied vertebrates, particularly mammalian herbivores with unique ecological roles, are disproportionately endangered (Pringle et al., 2023). These large herbivores are threatened not only by direct persecution for meat and other body parts but also by competition from advancing human populations (Gordon, 2009). For example, several species of wild cattle, rhinoceroses, and elephants have similar resource needs to human settlements, such as flat terrain, accessibility to water, and productive tropical climates. This scenario aligns with the biological theory of competitive exclusion, which posits that in a shared environment, complete competitors cannot coexist indefinitely (Hardin, 1960). The contemporary range contraction in the natural habitats of many species of large herbivores in the world (Ripple et al., 2015) lends support to this theory. Alarmingly, current species extinction rates far exceed historical background rates (Ripple, Abernethy, et al., 2016; Ripple, Chapron, et al., 2016), underscoring the need for sustained conservation efforts to maintain the remnant populations of these endangered large herbivores. Paradoxically, some endangered large herbivores, such as the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), can pose a challenge to the safety and economic well-being of local communities, presenting a unique paradigm for management, which must reconcile conservation with human welfare.

Historically, elephants were widely distributed in Asia, stretching from the river basins of the Tigris–Euphrates in the west to the Yangtze–Kiang River in the east, encompassing most of the present-day Asian countries (Shoshani & Tassy, 1996; Sukumar, 2003). However, elephant ranges in Asia have undergone massive contractions, resulting in dramatic population declines. Today, Asia elephants are found in less than 7% of their historical range. Among the myriad causes of elephant range contraction, the primary driver has been habitat loss, predominantly due to agricultural expansion and the development of human settlements (Leimgruber et al., 2003). Current estimates place the Asian elephant population at about 50,000, distributed across 13 range countries (Williams et al., 2020). As per population viability models, for long-term conservation, a population size of over 1000 elephants is essential (Sukumar, 1995). By invoking this prescription, it appears that the viability of elephant populations in many Asian countries is precarious and subject to various degrees of risk and change (Leimgruber et al., 2008).

In contrast with the dismal population scenarios for elephants in much of Asia, India stands as a notable exception. Home to more than 60% of the extant wild Asia elephant population, India's elephant numbers have been reported to be relatively stable (All India Elephant Estimation 2017, Government of India, 2020). India has four major regional elephant populations, occurring in the northern, northeastern, east-central, and southern areas. Elephant habitats in India extend beyond Protected Areas, also including multiple-use forest areas outside of the Protected Area network. In fact, <25% of the elephants’ distributional range in India falls within these Protected Areas (Project Elephant, Government of India, 2020). There are well-connected, large tracts of forests constituting elephant habitats outside the Protected Area Network. Thus, it is crucial to recognize that these habitats, although not within the Protected Area Network, are not synonymous with nonforested areas. In India, the term “elephant habitat” encompasses both these designated Protected Areas and other forests such as “reserved forests,” “protected forests,” and others including seminatural habitats such as forest plantations. This broader habitat definition accounts for around 80% to 85% of elephants’ distributional range across the country (Project Elephant, Government of India, 2020). Elephants are frequently found in human-dominated areas, which are characterized by a high interspersion of forests and agricultural land, with the latter often being more prevalent (Williams et al., 2001). Unfortunately, it is often in these mixed landscapes—particularly at the interfaces of elephant habitats and along their perimeters—where negative human–elephant interactions are most common (Sukumar, 2003; Desai & Riddle, 2015). These interactions can occur both within the boundaries of elephant habitats and in the adjoining human-dominated areas.

In India, all four regional populations face varying degrees of negative human–elephant interactions. More than 5,00,000 marginal families reportedly suffer due to these conflicts (Rangarajan et al., 2010). Furthermore, numerous human and elephant fatalities occur annually, contributing to the urgency of this issue (unpublished data, Project Elephant, Government of India). Efforts to address these interactions can broadly be classified into short- and long-term strategies. While short-term strategies focus on addressing the proximate causes or symptoms of conflict, long-term approaches target the root causes (Sukumar, 2003). One of the primary underlying causes of these conflicts is the direct competition for space between humans and elephants (Balasubramaniam et al., 1995; Sukumar, 2003). Despite extensive research on negative human–elephant interactions, the variability in site-specific conflict intensity calls for data-driven prioritization efforts for effective conservation management. Given the dynamic nature of these conflicts, regular reassessment of spatial-temporal trends in elephant populations and conflict patterns would be pertinent for moving towards evidence-based elephant conservation.

As a country harboring the largest viable Asian elephant populations, India is at a crucial juncture in balancing elephant conservation with human welfare to ensure the long-term survival of these majestic creatures (Rangarajan et al., 2010). Thus, an introspection of the institutional framework and the enablers of elephant conservation in India is both timely and essential.

Additionally, India's archetype of elephant conservation could offer important lessons for other range countries. With this context, this study delves into various aspects of elephant conservation in India. We provide historical perspectives, explore the current administrative policies, examine elephant population trends, and extract long-term lessons from India's conservation experiences. We also present an overview of human–elephant conflict scenarios, drawing on data from the centralized all-India database maintained by Project Elephant, Government of India. Site-specific data on all forms of negative human-elephant interactions, including incidents of elephant mortalities, were recorded by the respective State Forest Departments at the division level and subsequently communicated to the State headquarters on a periodic basis. From there, the State headquarters sends the accumulated data to Project Elephant annually. Our analysis for this article draws on this data spanning the years 2009–2020, providing a comprehensive overview of human-elephant conflicts across India. We also identify the major challenges currently facing elephant conservation and look ahead to future strategies aimed at sustaining viable elephant populations in the wild.

2 HISTORIC AND CURRENT CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES

India has a long history of elephant conservation (Bist, 2006). An ancient treatise on statecraft, Arthasastra, dating back to the Mauryan empire (300 BC to 300 AD), recommended the establishment of elephant sanctuaries. In these sanctuaries, hunting elephants was severely penalized, often with the death penalty for offenders (Bist et al., 2002). These protected areas, strategically located along state boundaries, bear a resemblance to the present-day situation in India. During British rule, the Tamil Nadu Wild Elephant Preservation Act of 1873 served as a legal precursor to modern elephant conservation (Bist et al., 2002). This was followed by the Elephant Preservation Act of 1879, which prohibited the killing of elephants throughout the country (Bist et al., 2002). After India's independence in 1947, one of the most powerful wildlife conservation laws in the world, the Wildlife (Protection) Act, was enacted in 1972 (Bist et al., 2002). The legislation accords the highest level of legal protection to elephants, regardless of whether they are in the wild or under human care. Furthermore, various legal instruments have been developed in India to safeguard the interests of elephants (Table 1).

| S. No | Legislation | Impact on elephants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 | Elephants are placed in Schedule-I of the Act. The Act prohibits hunting and advocates regulation and control in body parts. Important habitats are also declared as Protected Areas |

| 2 | Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 | In exceptional cases of allowing linear infrastructure and other nonforestry activities in elephant habitats, the Forest (Conservation) Act 1980 calls for robust mechanism for compensatory conservation mechanism, which includes wildlife management plan and appropriate mitigation strategies (WII, 2016) |

| 3 | Environmental (Protection) Act, 1986 | Important legislation that calls for regulation of activities in elephant corridors and around elephant habitats |

| 4 | Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 | The act prevents infliction of unnecessary pain or suffering on animals that include any living creature other than a human being. |

| 5 | Indian Forest Act, 1927 and the Forest Acts of the State Governments | Facilitates state control over forests |

Notwithstanding legal protection, elephant conservation has presented unique challenges, largely due to their extensive range requirements, propensity for direct conflict with human communities, and the perpetual demand for elephants’ body parts, particularly tusks. From the 1970s to the late 1990s, rampant poaching, fueled by the international ivory trade, decimated the male elephant population, skewing the sex ratio (male to female) (Sukumar, 2003). Even in some of the finest wildlife reserves, like the Periyar Wildlife Sanctuary in the Western Ghats, this imbalance was starkly evident with the male-to-female sex ratio recorded at 1:100 (Sukumar et al., 1998). Negative human-elephant interactions, previously perceived as minimal, started escalating in the 1980s in certain areas (unpublished data, Project Elephant; Sukumar et al., 2018). The 1990s marked the beginning of a period of significant economic progress in India, which necessitated the development of linear infrastructure and mineral mines, some of which were to pass through intact elephant habitats, resulting in habitat loss and fragmentation.

The combined impact of ivory poaching, escalating human-elephant conflicts, and increasingly fragmenting elephant habitats called for a mission-mode approach to elephant conservation. Furthermore, the limitations of individual Protected Areas and the Tiger Reserves became apparent, as these areas could not accommodate the extensive home ranges of elephants, which are typically five to 10 times larger than those of tigers. Thus, the need for a landscape approach to effectively conserve elephant populations was acknowledged. These recognitions heralded the launch of Project Elephant in 1992. Initiated as a centrally sponsored scheme, Project Elephant was designed to address critical issues facing elephant conservation and management.

2.1 Project elephant in India

Project Elephant functions under the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change of the Government of India and works in coordination with the State Forest Departments. It comprises a Steering Committee chaired by the central minister, which is made up of Chief Wildlife Wardens (the State's top-ranking wildlife officials), eminent scientists in the field of biodiversity conservation, and representatives from nongovernmental organizations. As a technical advisory body, the Steering Committee meets regularly to deliberate on crucial issues facing elephant conservation. One of the recent initiatives undertaken by Project Elephant is the establishment of the Central Project Elephant Management Committee. This committee was formed to ensure compliance with directives issued by the country's judiciary on matters related to elephant conservation. Project Elephant has further extended its conservation efforts by constituting the “Captive Elephant Health Care and Welfare Committee (CEHWC),” which aims to improve welfare and health conditions of captive elephants. Guiding the overarching strategy of Project Elephant is the National Wildlife Action Plan (2017-31), which is a comprehensive policy document that outlines India's approach to wildlife protection.

2.2 India's elephant reserves

The cornerstone of Project Elephant's management strategy lies in the concept of Elephant Reserves (ER henceforth). Unlike Protected Areas, which often focus on preserving the natural habitats of specific species, the concept of ERs emanates from an “integrated landscape approach.” This approach extends beyond traditional habitats to include areas such as elephant corridors and zones where human-elephant interactions frequently occur (Rangarajan et al., 2010). Consequently, managing ERs requires a collaborative effort that goes beyond the Forest Department's purview, entailing active coordination with other ministries, line agencies, and local communities.

This landscape-centric management philosophy, emphasizing habitat connectivity and the mitigation of negative human–elephant interactions, is also gaining traction in other Asian elephant range countries. For example, the Central Forest Spine master plan in peninsular Malaysia advocates for an integrated management approach similar to India's ERs, focusing on habitat contiguity through primary and secondary linkages (de la Torre et al., 2019).

As of 2023, India has established 33 ERs across 14 states, covering a total area of 80,777 km2 (average ± SD = 2448.8 ± 2604.5 km2, Range = 23.5–13440 km2). This marks an almost 24% increase from the 65,000 km2 reported in 2010 (Rangarajan et al., 2010). The sizes of these ERs varies considerably, with the smallest being Singphan (23.5 km2) in Nagaland and the largest being Singhbhum (13,440 km2) in Jharkhand. On average, these ERs consist of around 78.9% forest cover, with the remainder comprising non-forest areas of diverse land use.

3 DISTRIBUTION AND POPULATION TRENDS

3.1 Present distribution

As per the 2017 assessment, elephants in India are found across over 1,63,000 km2 of heterogeneous habitats, spanning four main elephant-bearing regions (Project Elephant, Government of India, 2020). Within these regions, researchers have identified ten major population complexes, which function similar to meta-populations (Rangarajan et al., 2010). Project Elephant maps elephant distribution once every 5 years, starting from 2017, to monitor changes in their range. Recent studies indicate an increase in the distributional range of elephants, particularly in the east-central region (Natarajan et al., 2023). This range expansion is a consequence of elephant dispersal into new areas, which has led to increased instances of negative human–elephant interactions (Natarajan et al., 2023).

3.2 Population trends and estimation techniques

Before India's independence in 1947, acclaimed forester F.W. Champion made one of the earliest attempts to estimate the elephant population along the Himalayan foothills (Rangarajan et al., 2010). The first systematic country-wide estimate of the elephant population in India was carried out during the 1980s under the guidance of the late J.C. Daniel of the Bombay Natural History Society and conducted by the Asian Elephant Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This effort registered a population of 14,800–16,455 elephants in India (Bist, 2002). After Project Elephant came into being, a more systematic approach to population estimation was adopted, mandating a nationwide count every 5 years. In 2005, Project Elephant further refined its methodology by emphasizing the recording of population structure details. This marked the introduction of the Synchronized Elephant Population Estimation (SEPE) approach. In this approach, India's various elephant range states are coordinated to conduct surveys simultaneously to avoid duplication, given that elephant ranges in India often encompass two or more states. The SEPE consists of three distinct methods: (i) block count, which is a census without relying on techniques rooted in sampling theory; (ii) dung-based distance sampling, entailing foot transects to enumerate elephant dung, which is then used to estimate absolute densities of elephant populations; and (iii) water hole count, aimed at recording the age and sex structure of the elephant population by observing elephants at water holes (Varma et al., 2012). In the 2017 assessment, Project Elephant expanded the scope to include mapping elephant distribution as an additional objective.

India's elephant population estimation techniques have attracted internal criticism (Rangarajan et al., 2010; Jathanna et al., 2015) for their lack of statistical rigor, which some argue hinders the ability to detect crucial demographic changes. Critics have pointed out that the block count method does not adequately account for variable detectability and spatial sampling variations (Jathanna et al., 2015). Similarly, the dung-based distance-sampling approach faces challenges, as it relies on parameters such as elephant defecation rates and dung decay rates, which vary widely across India's diverse eco-climatic zones (Jathanna et al., 2015). In response to these concerns, the Government of India embarked on a synchronized approach for tiger and elephant population estimation in 2021. This new method experiments with the genetic mark–capture–recapture method (e.g., Gray et al., 2014), offering a potentially more robust way to estimate elephant populations across India. In addition to formal government-driven population estimation, numerous organizations have been encouraged to conduct population estimation at various sites (Madhusudan et al., 2015; Jathanna et al., 2015), contributing to more comprehensive and varied data collection.

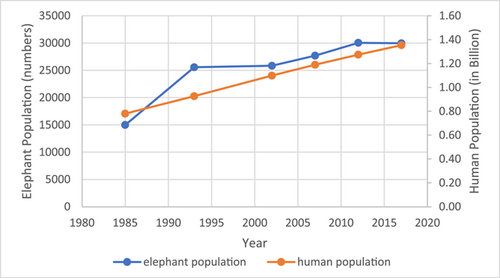

Notwithstanding the varying methods of population estimation, country-wide elephant population estimates have been available in India since 1985 (Figure 1). The overall trend from this data indicates an initial population increase from 1985 to 1990. However, this growth subsequently leveled off, with numbers oscillating between 25,000 and 30,000 elephants. The population increase observed in the late 1980s raises questions about possible sampling artifacts, particularly as it was the first-ever nationwide effort to assess elephant populations. Interestingly, although India's elephant population is just 0.0021% of its human population, both populations have shown similar trends over the last three decades (Figure 1). The most recent all-India elephant population estimation, carried out in 2017, revealed that the southern region harbors the largest population, c. 14,000 elephants, followed by the northeastern region (c. 10,000 elephants), east-central region (c. 3100 elephants), and the north-western region (c. 2000 elephants) (Project Elephant, Government of India, 2020). The recent elephant population estimations carried out independently by the State Forest Departments of the southern states broadly align with the 2017 estimates provided by Project Elephant (TNFD, 2023; KFD, 2023).

4 TRENDS IN NEGATIVE HUMAN–ELEPHANT INTERACTIONS

The IUCN's Species Survival Commission (SSC) for Human-Wildlife Conflict and Coexistence defines human–wildlife conflicts as “struggles that emerge when elephant presence or behavior poses actual or perceived, direct and recurring threats to human interests or needs, leading to disagreements between groups of people and negative impacts on people and/or wildlife” (IUCN, 2023). This definition can be applied to negative human-elephant interactions, which comprise a range of detrimental effects on both people and elephants. From the human perspective, these interactions can lead to a combination of direct and indirect costs (Barua et al., 2013). Such indirect costs include living in perpetual fear, the loss of breadwinners in the family, health issues associated with crop guarding, psychological stress and trauma, impaired education for children, and various others that are often difficult to quantify (Thondhlana et al., 2020). The direct costs of negative human–elephant interactions to people include property losses in the form of damage to cultivated crops, farming equipment, houses, and grain storage structures, as well as occasional human casualties (Sukumar, 2003; Natarajan et al., 2021, 2023).

4.1 Human deaths attributed to negative human–elephant interactions

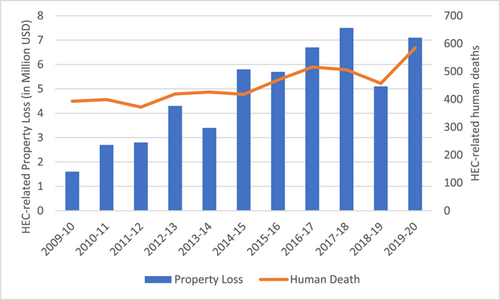

Although only a small fraction of interactions between people and elephants result in human fatalities, the loss of human life in conflict can have societal ramifications and is therefore considered the most acute form of negative human–elephant interaction. Thus, as highlighted by Natarajan et al. (2023), developing strategies to minimize threats to people's lives and livelihoods is crucial to fostering community support for elephant conservation. Despite various mitigation efforts, data indicate a steady rise in the average number of human deaths attributed to negative human–elephant interactions (Figure 2). Between 2009 and 2020, there were a total of 4642 fatalities, averaging 450 deaths per year (±63.7), as a result of these interactions. This increase not only indicates an actual increase in conflict incidences but also improvements in reporting and response mechanisms. Regionally, the east-central region experienced the highest toll, losing 1931 human lives, accounting for 41.5% of the reported conflict-related human deaths during this period. This is notable as this region harbors only 10% of India's elephant population. In comparison, the northeastern region recorded 1,605 human deaths, followed by the southern region (n = 962) and the northern region (n = 144).

4.2 Property losses attributed to negative human–elephant interactions

The phenomenon of elephants feeding on cultivated crops is as ancient as the advent of settled agriculture around 10,000–12,000 years ago (Pandey, 2021). This behavior, where elephants show a preference for nutrient-rich and palatable cultivars, is thought to be an extension of their “optimal foraging strategy (Sukumar, 2003).” This ecological theory explains how animals maximize their energy intake in the shortest possible time. In India, the type of crops raided by elephants varies based on the region. Common targets include paddy (Oryza sativa), wheat (Triticum aestivum), different species of maize and millets, sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), cultivated palms including coconut (Cocos nucifera), arecanut (Areca catechu), palmyra palm (Borassus flabellifer), fruits like mango (Mangifera indica), banana (Musa spp.), jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), pineapple (Ananas comusus), and a variety of vegetables (Sukumar, 1985). Between 2009 and 2020, the Indian government compensated affected communities an annual average of 4.79 (±1.97) million USD for property losses caused by elephants. In general, these property losses have been steadily increasing, as exemplified by the growing amount of ex gratia payments (Figure 2).

4.3 Elephant mortalities attributed to negative human–elephant interactions

Although the deep-rooted religious and cultural affinity for elephants in India fosters relatively high tolerance among the population, incidents of retaliatory killings of elephants are unfortunately widespread. In many of India's elephant habitats, crop raiding is not only a problem associated with elephants but also with other wildlife like wild pigs (Sus scrofa) and Cervid and Axis deer, which occur in sympatry and often damage crops. In an attempt to protect their crops, farmers sometimes resort to illegal and dangerous methods. Instead of using energizers to regulate the power supply and deliver a powerful but nonlethal shock to animals, concealed wires with power drawn directly from the mains are set up, primarily targeting wild pigs, which are considered inveterate crop raiders. Between 2009 and 2019, an annual average of 60 (±12.5) elephants died from electrocution in India. Although the large majority of reported incidences were due to crop-guarding measures, a fraction of elephant electrocution cases can also be attributed to sagging power transmission wires. Compared with electrocution, retaliatory killing of elephants in the form of poisoning (n = 64, 2009–2020) is rare but still occurs.

5 LINEAR INFRASTRUCTURE-RELATED THREATS TO ELEPHANTS

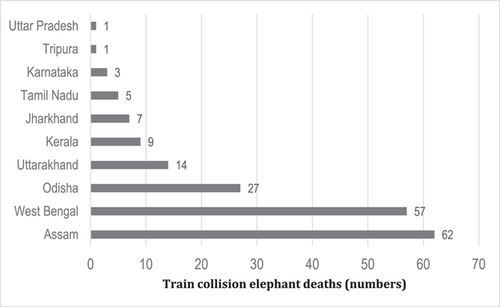

India's linear infrastructure development and corresponding mineral mining have kept pace with its rapidly growing economy. During the last decade, India's railways, considered the main artery of the country, have been modernized, marked by a doubling of single lines, energization, an increase in operational speed, and a consequent increase in traffic volume. This expansion has had a notable impact on wildlife, with approximately 1340 km of railway network cutting across elephant habitats. Between 2009 and 2020, railway-related incidents caused the deaths of 176 elephants, at an annual average of 15.5 (±5.8). Elephant deaths due to railway lines were particularly high in the states of Assam and West Bengal, located in the northeastern region, followed by Odisha state in the east-central region and other states across India (Figure 3).

Alongside railways, India's elephants also face challenges from road networks, with c. 10,790 km of national highways and state highways passing through elephant habitats. Although direct road-induced elephant collisions are fewer than those on railways, it is recognized that roads have far-reaching fragmentation effects, which require urgent attention. In addition to the transportation network, c. 300 km of irrigation canals and c. 7230 km of power transmission lines pass through elephant habitats, adding to the complexity of habitat fragmentation. Direct mortality due to these other forms of physical infrastructure is comparatively low. However, with the expanding network of such infrastructures in elephant habitats, there is a concern that, as with increasing fragmentation, elephant mortalities could also increase. In recognition of these growing threats, emphasis is currently being placed on mitigation measures for which a basic guideline (WII, 2016) is in place.

6 MAJOR CONTEMPORARY CHALLENGES AND WAY FORWARD

Invoking a flagship-centered conservation approach has been one of India's main biodiversity conservation strategies (National Wildlife Action Plan 2017–2031, MoEFCC, Government of India, 2017), underscoring its commitment to protecting its rich natural heritage. Elephants, recognized not only as umbrella and keystone species in biodiversity conservation due to their extensive home range needs and ecological roles in the tropical forest ecosystem (Fernando & Leimgruber, 2011; Sekar & Sukumar, 2013), also garner favorable public opinion towards conservation (Vasudev et al., 2020). Reinforcing its commitment to conservation, India has accorded the elephant the status of national heritage animal (Pandey, 2022). Although the country is consolidating its efforts in elephant conservation, several key challenges require special focus.

6.1 Insularization of elephant habitats

In India, even the most intact and continuous elephant ranges, like the Brahmagiri–Nilgiri–Eastern Ghats, which supports the single largest elephant population, are surrounded by areas of human activity. With increasing human population pressure and concomitant resource needs, the remnant elephant habitats could potentially become insular. Although mainstreaming elephant conservation into infrastructure development is acknowledged as the mainstay of India's sustainable development goals, its on-ground implementation remains a significant challenge.

To minimize the isolation of elephant habitats, maintaining a network of functional elephant corridors is of paramount importance. While elephant corridors in forests enjoy legal protection, those occurring outside these areas are under threat. Recognizing that timely identification of elephant corridors can serve as a precursor to securing them, Project Elephant published a report on 150 identified elephant corridors across India (Project Elephant 2023). These corridors were identified and communicated to Project Elephant by the respective State Forest Departments based on (i) previous pan-India publications (e.g., Menon et al. 2005, 2017; Rangarajan et al., 2010), (ii) site-specific independent evaluations (e.g., Johnsingh et al., 2006), and (iii) site-specific regular monitoring of elephant movements by the State Forest Departments. To ensure the accuracy and relevance of these identified corridors, Project Elephant constituted state-specific technical committees for ground validation (Project Elephant 2023). Although the current list of corridors in the report is not exhaustive, it underscores the concerted efforts required to monitor and restore elephant corridors to maintain long-term population viability. Project Elephant is contemplating implementing periodic monitoring of elephant corridors, using metrics such as elephant movement patterns alongside population estimation. This approach aims to keep the status of the corridors and their landscape relevance up-to-date (Project Elephant 2023).

6.2 Increasing concerns over habitat quality

For elephants, being large herbivores reliant on vegetation, variations in habitat quality can have profound effects on their populations (Owen-Smith, 2009). Several factors, like changes in water regime, over-extraction of forest resources, and recurrent forest fires, can affect the inherent quality of elephant habitats (Desai & Baskaran, 1996). One of the major factors contributing to the reduction in quality of elephant habitats is the spread of invasive plant species like Lantana camara, Opuntia dillenii, Chromolaena spp., Parthenium hysterophorus, Senna spp., and many others (Wilson et al., 2013). Substantial financial and human resources are being invested to facilitate the eradication of invasive weeds from natural habitats (Rishi, 2009). However, there is still no consensus on the most effective approach to managing them. The prevailing scientific views on the management of invasive species like L. camara are polarized: some practitioners favor the judicious use of fire to curb their spread, while others argue that forest fires can further disturb intact vegetation communities (Bhagwat et al., 2012; Hiremath & Sundaram, 2005). Recent initiatives have demonstrated the successful eradication of invasive plants conditional on active restoration of native vegetation. Consequently, scientific monitoring and evaluation of invasive species management are becoming increasingly important for the informed and effective management of elephant habitats.

6.3 Environmental dispersal of elephants into new areas

Dispersal is a key behavioral mechanism that maintains the genetic diversity and demographic viability of wildlife populations (Caughley, 1977). In elephants, this phenomenon transcends individual natal dispersal and manifests as environmental dispersal, where entire herds move from previous home ranges, possibly triggered by saturated habitat conditions (Caughley, 1977; Natarajan et al., 2023). These dispersed herds of elephants are increasingly venturing into human-dominated landscapes, causing heightened negative human-elephant interactions (Natarajan et al., 2023). India's east-central region, which experiences the highest levels of negative human–elephant interactions, has been witnessing large-scale environmental dispersals. Given that there is likely a complex set of underlying reasons triggering the environmental dispersal of elephants, managing them presents a challenging task. In response to these novel conflict situations, the government has developed a manual in different Indian languages. The manual is designed to assist field managers in implementing basic conflict mitigation strategies in diversity of contexts and situations (Project Elephant, Government of India & WWF-India, 2022).

7 WAY FORWARD

Overall, the major enablers of elephant conservation in India include the cultural significance of the species that generates strong public support for elephant conservation, the relatively high tolerance of local communities towards wildlife in general, strong legislation, and the institutional framework and capacity to implement conservation priorities. Remarkably, Indian elephant populations have been holding steady and even growing in some landscapes. This is a significant achievement when viewed against the backdrop of global elephant conservation standards, especially in the face of major threats like ivory poaching that have been decimating African elephant populations (Wittemyer et al., 2013). The stability of elephant numbers in India, despite the country's rapid population growth and economic development over the past three decades, is a testament to the effectiveness of its conservation strategies.

Elephant habitats in India cover about 5% of the country's land area. Thus, even in the largest elephant landscape complexes, interactions with people are inevitable. Therefore, human–elephant coexistence is the only possible model for elephant conservation in India, and likely across Asia as a whole. Embracing the realities of elephant conservation, it is evident that conflict will continue to occur in interface areas. However, although complete resolution of these conflicts might not be feasible, intelligent and strategic management is essential to maintain them at socially tolerable levels without unduly compromising on conservation priorities.

Although negative human–elephant interactions are a widespread issue across the four regional elephant populations in India, in the east-central region, the problem is particularly acute. Addressing it has been complex and challenging, especially in light of elephant dispersal into new areas, spreading the zone of conflict. In an effort to maintain and foster local tolerance in these areas, Project Elephant has contemplated the idea of increasing the ex gratia monetary payments to local communities, particularly in the event of human deaths. For crop and property losses, ex gratia is already being paid, and many states have introduced online portals to reduce processing time. For example, Odisha and Karnataka have robust online portals and mobile-based applications such as ANUKAMPA (in Odisha) and e-Parihara (in Karnataka) that have increased the overall transparency in the ex gratia payment process. Although a seemingly attractive opportunity, the nuances of implementing contributory insurance schemes involving local communities warrant careful and objective assessment. In addition to timely monetary benefits, an increasing focus is being placed on improving the response time to negative human–elephant interactions. There is also an increased recognition that involving local communities as primary stakeholders in conservation and timely conflict resolution is crucial. In many Indian states, primary conflict response teams from the Forest Department often include village volunteers who aid in monitoring elephants in human-use areas, enabling them to disseminate early warning messages throughout the communities.

Life history traits and the corresponding ecological requirements of elephants necessitate the preservation of large and contiguous tracts of natural tropical forests and associated ecosystems for their conservation (Blake & Hedges, 2004; Sukumar, 2003). Based on this maxim, prioritizing the maintenance of resilient landscapes becomes crucial for elephant conservation. A key initiative towards this goal is enhancing the management of ERs. Project Elephant has embarked on the current Management Effectiveness Evaluation of ERs, aiming to identify reserve-specific management gaps. Nevertheless, given the high level of heterogeneity of land use in ERs, coming up with a specific management framework remains a challenge. To address this issue, Project Elephant has been coordinating with elephant range states to devise an Elephant Conservation Plan (ECP). The ECP will include landscape-level management prescriptions applicable to all types of land within ERs, and will be coordinated by the field director of each ER. Currently, the ECP is being prepared for a few ERs on a pilot basis to assess its suitability and adequacy under field conditions. As the interests of elephant conservation can often clash with those of other government agencies like road transport, railways, mining, electricity, and irrigation, there is an emphasis on proactive interministerial engagement. Such collaboration is essential to ensure that economic development projects can be harmonized with India's biodiversity conservation goals.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ramesh K. Pandey: Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Satya P. Yadav: Conceptualization, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing. K. Muthamizh Selvan: Formal analysis, project administration, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Lakshminarayanan Natarajan: Formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Parag Nigam: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support provided by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India. We are grateful to the state forest departments of the elephant range states for providing elephant-related data from the field. We thank the Director of the Wildlife Institute of India and the Director of the Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research for the institutional support. The help provided by Udhaya Raj, Raju Rawat, and Kirti Bisht in preparing maps and collating data from the states is greatly appreciated.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable—no new data generated.