Novel pathogenic variants in filamin C identified in pediatric restrictive cardiomyopathy

Funding information: Children's Cardiomyopathy Foundation; American Heart Association Established Investigator Award, Grant/Award number: 13EIA13460001; AHA Postdoctoral Fellowship Award, Grant/Award number: 12POST10370002.

Communicated by Madhuri Hegde

Abstract

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is a rare and distinct form of cardiomyopathy characterized by normal ventricular chamber dimensions, normal myocardial wall thickness, and preserved systolic function. The abnormal myocardium, however, demonstrates impaired relaxation. To date, dominant variants causing RCM have been reported in a small number of sarcomeric or cytoskeletal genes, but the genetic causes in a majority of cases remain unexplained, especially in early childhood. Here, we describe two RCM families with childhood onset: one in a large family with a history of autosomal dominant RCM and the other a family with affected monozygotic, dichorionic/diamniotic twins. Exome sequencing found a pathogenic filamin C (FLNC) variant in each: p.Pro2298Leu, which segregates with disease in the large autosomal dominant RCM family, and p.Tyr2563Cys in both affected twins. In vitro expression of both mutant proteins yielded aggregates of FLNC containing actin in C2C12 myoblast cells. Recently, a number of variants in FLNC have been described that cause hypertrophic, dilated, and restrictive cardiomyopathies. Our data presented here provide further evidence for the role of FLNC in pediatric RCM, and suggest the need to include FLNC in genetic testing of cardiomyopathy patients including those with early ages of onset.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cardiomyopathy (CM), a disease of heart muscle causing systolic and/or diastolic dysfunction, is a common cause of cardiac failure in children (Wilkinson, Westphal, Ross, Dauphin, & Lipshultz, 2015). Phenotypes include dilated (DCM), hypertrophic (HCM), restrictive (RCM), and arrhythmogenic forms (AVC), as well as left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC). RCM, the rarest of the cardiomyopathies, is defined as restrictive ventricular physiology in the presence of normal or reduced diastolic volumes, normal or reduced systolic volumes, and normal ventricular wall thickness (Vatta & Towbin, 2011). RCM accounts for up to 5% of cardiomyopathies in children, with the majority having no specific cause identified. The prognosis in children with RCM is poor—nearly 50% of patients die or undergo transplant within 3 years of diagnosis (Russo, 2005; Webber et al., 2012). Familial RCM is reported in 30% of all cases and both autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant inheritance have been described (Denfield & Webber, 2010). In some families with autosomal dominant CM, both HCM and RCM have been identified, suggested shared genetic causes (Kaski, Biagini, Lorenzini, Rapezzi, & Elliott, 2012). To date more than 100 genes have been implicated in various forms of CM (Tariq & Ware, 2014; Ware, 2015; Ware, 2017). These genes are involved in sarcomeric cytoskeletal, desmosomal or mitochondrial organization, metabolic processes, and other additional cellular functions (Harvey & Leinwand, 2011).

Despite progress in identifying various genetic causes for cardiomyopathies, little is known about the genetic etiology of RCM. To date, dominant pathogenic variants causing RCM have been reported in DES, ACTC1, TNNI3, TNNT2, TPM1, MYL3, MYL, MYPN, TTN, BAG3, FLNC, TTR, and MYH7, but the majority of cases are considered idiopathic (Towbin, 2014). However, recent studies of idiopathic RCM cohorts tested using panels of 100–200 CM-related genes show some success in identifying additional likely pathogenic variants in genes including: DES, LAMP2, LMNA, BAG3, JUP, TTN, and others, with 50%–60% of patients having an identified potentially pathogenic variant (Gallego-Delgado et al., 2016; Kostareva et al., 2016). Although previous reports indicate yields of clinical genetic testing around 20% for RCM (Ackerman et al., 2011), data are limited. Identification of further genetic causes for RCM will be the first step for understanding the disease mechanisms, which may eventually lead to gene-specific diagnosis and potential therapy.

Filamins are a group of large proteins important for structural integrity of cells that act by crosslinking actin filaments and anchoring membrane proteins to the cytoskeleton. Variants in FLNC have not only been reported in RCM patients but also in other cardiomyopathies and skeletal muscle diseases (Brodehl et al., 2016; Valdés-Mas et al., 2014; Vorgerd et al., 2005). In this study, we investigated two families with early onset RCM, identified FLNC variants using an exome sequencing (ES) approach, and performed in vitro functional analyses. Using these approaches, we sought to expand the current spectrum of genetic variants associated with familial RCM.

2 METHODS

2.1 Ascertainment of familial RCM and ethical considerations

Patients underwent clinical evaluation by a pediatric geneticist and pediatric cardiologist at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) or Children's Hospital of Wisconsin. Patients and family members enrolled in a research study approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at CCHMC or Indiana University. Written informed consent for participation in this study, as well as publication of clinical data of the affected individuals was obtained from the families. All the methods applied in this study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) of the World Medical Association concerning human material/data and experimentation. Genomic DNA of six individuals from Family 1 (Figure 1a) and five individuals from Family 2 (Figure 2a) was extracted from whole peripheral blood leukocytes following a standard DNA extraction protocol (Promega, Madison, WI).

2.2 Exome sequencing

For Family 1, exome sequencing (ES) was performed on a research basis. Genomic DNA (2 μg) from proband IV-2 (Figure 1a) was used for enrichment of human exonic sequences with the NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Human Exome v2.0 Library (2.1 million DNA probes; Roche NimbleGen, Inc., Madison, WI). Sequencing was performed with 50 bp paired-end reads using Illumina (San Diego, CA) GAII (v2 Chemistry) to a mean depth of approximately 56×. All sequence reads were mapped to the reference human genome (UCSC hg 19) using the Illumina Pipeline software version 1.5 featuring a gapped aligner (ELAND v2). Variant identification was performed using GATK (McKenna et al., 2010). Amino acid changes were identified by comparison to the UCSC RefSeq database track. A local CCHMC realignment tool was used to minimize the errors in SNP calling due to indels. Exome data were initially screened for more than 300 genes known for CM or related phenotypes. Our filtering strategy removed previously reported variants in databases such as dbSNP (Sherry et al., 2001) and NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) (https://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), in addition to non-coding variants. Remaining variants were tested for segregation with disease in the family, and further subject to pathogenicity prediction programs including: Polyphen-2, SIFT/PROVEAN, MutationTaster, and HOPE (Adzhubei et al., 2010; Choi, Sims, Murphy, Miller, & Chan, 2012; Schwarz, Cooper, Schuelke, & Seelow, 2014; Venselaar, Te Beek, Kuipers, Hekkelman, & Vriend, 2010).

For Family 2, DNA samples were sent to the Advanced Genomics Laboratory at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) for clinical ES of the parent and proband trio. In brief, after enriching for coding exons with solution based hybridization, an Illumina HiSeq 2500 was used for sequencing. Analysis of depth of coverage across exomes was performed with the GapMine software (MCW) with a minimum average depth of 85×. Sequencing variants were interpreted with the Carpe Novo software package (MCW). For this clinical pipeline, all identified variants were assessed for potential clinical significance. In addition to filtering variants based on quality and allele frequency, Carpe Novo uses multiple algorithms and databases to assess variants including bioinformatics predictions on protein function and structure (Polyphen-2 and SIFT), evolutionary conservation at the affected residues, changes to known splice site donors or acceptors, and presence or absence of the variant in aggregate databases such as dbSNP, HGMD, or OMIM (Stenson et al., 2003; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM®, https://omim.org/).

2.3 Variant screening and validation

Primers (Supp. Table S1) were designed covering exonic regions containing potential candidate variants (FLNC, MYPN, and PKP2 in Family 1 and FLNC and SYNE2 in Family 2). PCR products were sequenced on an ABI (Foster City, CA) 3730XL Genetic Analyzer using BigDye Terminator (ABI). Sequence analysis was performed via FinchTV 1.4.0 (https://www.geospiza.com). All positive findings were confirmed in a separate experiment using the original genomic DNA sample as template for new amplification and bi-directional sequencing reactions. The FLNC p.Pro2298Leu and FLNC p.Tyr2563Cys variants (Refseq NM_001458.4) were determined to be pathogenic according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) 2015 guidelines for variant interpretation (Richards et al., 2015) based on data presented here (see section Results). FLNC variants were submitted to ClinVar and have been assigned the following ClinVar accession numbers: SCV000787752 (p.Pro22298Leu) and SCV000787753 (p.Tyr2563Cys).

2.4 In silico protein homology modeling and viewing

SWISS-MODEL (Biasini et al., 2014) modeled the Ig domains 20–21 of FLNC to depict amino acid position 2298. The amino acid sequence of these domains was queried, and the template model most closely matching FLNC sequence was selected. This model was based on the known crystal structure of FLNA's Ig 20–21 domains (PDB 4P3W). A known crystal structure for FLNC Ig23 (PDB 2NQC) served as model to view amino acid position 2563. YASARA (Krieger & Vriend, 2014) was used to view both protein structures.

2.5 Cell culture, plasmid transfection, and immunocytochemistry

A human FLNC clone was purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD, catalog number RG212462) in a mammalian expression vector pCMV-AC-GFP. Mutagenesis was performed using primers designed (Supp. Table S2) for both the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and the Infusion HD cloning kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Validations of full-length FLNC pCMV-AC-GFP plasmids with wild-type and mutant transcripts were carried out using primers listed in Supp. Table S3. Both a standard calcium-phosphate method and Neon electroporation (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) were used for transfections. For calcium-phosphate transfections, C2C12 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA; CRL-1772) were cultured with 2 ml Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Pittsburgh, PA) and 1% penicillin-streptomyocyin (Gibco, Waltham, MA) in a 2 well (4.0 cm2) Lab-Tek chamber slide (Nunc, Rochester, NY) to reach 60% confluence on the day prior to transfection. To transfect, 5 μg of pCMV-AC-GFP FLNC wild-type or mutant plasmids were combined with 8 μl of 2 M CaCl2. This mix was added dropwise to 62.5 μl 2X HEPES buffered saline. After 30 min of precipitation, the combined solution was added to the culture media and incubated overnight. After incubation, the transfection media was replaced with 2 ml fresh media. For Neon electroporation, 100,000 C2C12 cells and 0.75 μg of plasmid DNA were used in each transfection using electroporation conditions of 1,650 V, 10 ms pulse width, and pulse number 3. Cells were plated into two well chamber slides with 2 ml of the above described DMEM.

Forty-eight to 72 hr post transfection, cells were prepared for immunocytochemistry. All steps were carried out at room temperature. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times for 15 min, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min followed by repeated PBS washes, and then permeabilized with 1% Triton-X100 (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 30 min. Following permeabilization, blocking was carried out with 5% non-fat dried milk and 1% goat serum (Invitrogen) in 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS for 60 min. The following primary antibodies were incubated with cells for 3 hr: desmin (polyclonal rabbit α-mouse 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; ab8592) and FLNC (polyclonal goat α-mouse 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX; sc-48496). Cells were washed with PBS and then incubated for 60 minutes in the following secondary antibodies, all at 1:100 dilutions: goat α-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA); donkey α-goat Alexa Fluor 594 (ThermoFisher); and F-actin was detected with the Phalloidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 594 (ThermoFisher). The slides were then rinsed in PBS buffer for 15 min, mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI for nuclei counterstain (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and examined under a fluorescence (Nikon Eclipse E400, Melville, NY) or confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Apotome, Thornwood, NY).

2.6 Pathology

Explanted heart tissue was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hr at room temperature before embedding in paraffin (FFPE), sectioning, and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or trichrome. Additionally, a portion of the ventricle was fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer, and sectioned to one cubic millimeter for processing and imaging by transmission electron microscopy.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Phenotypic evaluation

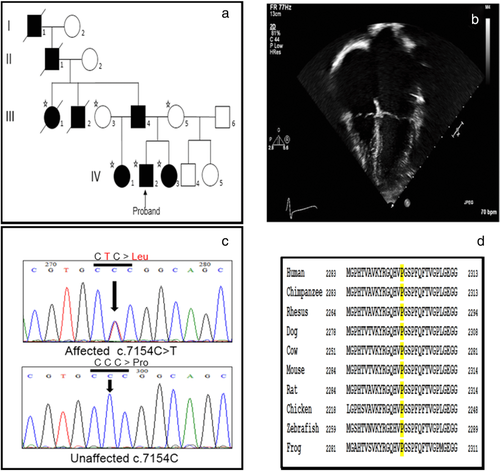

Family 1 showed a typical autosomal dominant mode of inheritance (Figure 1a), and all affected members presented with isolated RCM diagnosed at early ages. The family's race is African American. The proband was given a diagnosis of RCM at age 8, and upon echocardiogram was found to have an indexed left atrial volume of 72 ml/m2, right atrial enlargement, and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (Figure 1b). Cardiac catheterization confirmed the diagnosis of RCM (Rindler, Hinton, Salomonis, & Ware, 2017). He underwent transplant at the age of 11 years. The patient's sister was followed by echocardiography due to the family history of RCM and first showed evidence of biatrial enlargement at the age of 4 years. She underwent cardiac catheterization and was given a diagnosis of RCM at the age of 5 years and was listed for transplant which occurred at the age of 7 years. The paternal aunt was diagnosed with RCM at the age of 3 years and the paternal half-sister was diagnosed under the age of 10 years. All of the affected individuals presented disease symptoms without evidence of myopathy or other extra-cardiac findings. Clinical genetic testing for 10 genes (MYBPC3, MYH7, ACTC1, DES, MYL2, MYL3, TNNI3, TNNT2, TPM1, and EMD) was performed as part of the clinical diagnostic evaluation and no sequence variants were reported by the clinical testing laboratory.

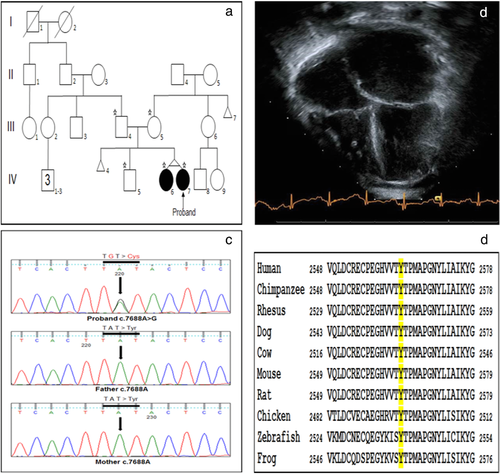

The proband in Family 2 is a 1-year-old Caucasian female who presented with acute onset of unilateral weakness and was found to have a left sided thromboembolic middle cerebral artery stroke. Evaluation for etiology revealed classic phenotypic changes consistent with RCM including normal ventricular dimension and systolic function with massively dilated atria (Figure 2b). Of note, the child had an echocardiogram in the perinatal period that was normal aside from a small muscular ventral septal defect with restrictive left to right shunt. Due to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance, she was listed for heart transplant shortly after diagnosis and successfully transplanted months later. Family echocardiographic screening revealed that her twin sister had similar phenotypic findings of RCM while her brother, mother, and father were all unaffected (Figure 2a). The twin sister progressed over months to require heart transplant listing and was successfully transplanted as well. Of note, each twin also presented with extra-cardiac phenotypes at the time of RCM diagnosis, including unspecified developmental delay, hypotonia, dysmorphic facial features, and clasped thumbs. Further, they each demonstrated kidney dysfunction of unclear etiology by three years of age, post heart transplant.

3.2 Pathology

Explanted heart tissue from the proband in Family 1 was processed for both histology and transmission electron microscopy (EM). H&E staining revealed some myocyte hypertrophy, nuclear size changes, and occasional central nuclei (Figure 3a), whereas trichrome staining at lower magnification showed some differences in fiber sizes and lacy interstitial fibrosis (Figure 3b). EM of the explanted tissue showed essentially normal ultrastructure; there were no lipid or glycogen deposits. Relevant for FLNC-related myopathies, there were no inclusions or depositions observed. Mitochondrial organization and sarcomere structure (Figure 3c,d) appeared normal and regular with no disarray of the type frequently seen in patients with MYH7 or MYBPC3 variants (Wessels et al., 2015; Witjas-Paalberends et al., 2013). The proband and twin sister from Family 2 also had explanted heart tissue processed for EM. Both proband (Figure 3e) and sister (Figure 3f) also demonstrate regular sarcomeric structure, with no evidence of myofibril degeneration or signs of irregular mitochondria organization, aggregates, or depositions.

3.3 Exome analysis

After variant filtering, we identified 3 candidate variants in the proband in Family 1. These included variants in MYPN (p.Ser1282Arg), PKP2 (p.Val798Ile), and FLNC (p.Pro2298Leu). These sequence changes were tested in additional family members and only the FLNC missense variant p.Pro2298Leu (c.6893C>T; NM_001458.4) cosegregated with the RCM phenotype in the family, supporting a dominant mode of inheritance (Figure 1c). The p.Pro2298Leu variant is located in exon 41 of FLNC and falls in the immunoglobulin-like (Ig) 20 (a.a. 2244–2306) domain of the protein. This variant is not present in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) (Lek et al., 2016). Additionally, the variant is located outside the region of homology that transcribed FLNC shares with the identified FLNC-like pseudogene (Odgerel, van der Ven, Fürst, & Goldfarb, 2010).

Clinical ES of the trio and filtering strategies were used to identify potential disease causing variants in the proband of Family 2. Ultimately, three variants in two genes, FLNC and SYNE2 (a gene associated with autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy), were filtered as being potentially clinically important. Each SYNE2 variant (p.Val1688Ile and p.Lys4931Arg) was inherited from a healthy parent (Supp. Figure S1). Additionally, these variants were predicted to be benign by pathogenicity prediction, were found in variant databases such as ExAC and dbSNP, and neither twin presented classical signs of Emery-Dreifuss by two years of age. The identified FLNC variant p.Tyr2563Cys (c.7688A>G; NM_001458.4) was present in both twins and absent in unaffected parents and sibling (Figure 2c) indicating it was de novo. It was not found in ExAC or dbSNP, is located in Ig domain 23, and was confirmed to be present in the functional FLNC gene and not its pseudogene.

3.4 In silico pathogenicity prediction

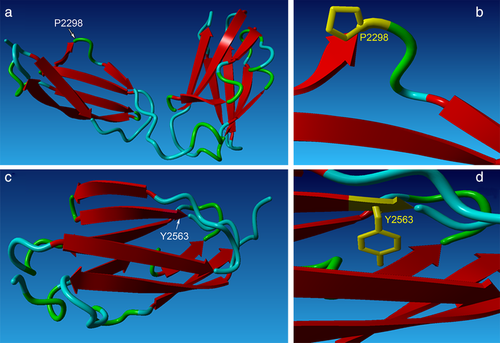

Both the autosomal dominant p.Pro2298Leu and de novo p.Tyr2563Cys variants in FLNC were unanimously predicted to be pathogenic using bioinformatic programs Polyphen-2, SIFT/PROVEAN, and Mutation Taster (Supp. Table S4). Further, the program HOPE (Venselaar et al., 2010) was used to discover and analyze potential changes to protein structure resulting from each variant (Supp. Table S4). Proline at position 2298 of FLNC, as well as its respective triplet codon (CCC) in the gene, are evolutionary conserved across species suggesting an important role of this residue in protein function (Figure 1d). Prolines are known to be very rigid and therefore induce a special backbone conformation which might be required at this position. All filamins consist of an N-terminus actin-binding domain followed by 24 antiparallel β-sheet repeats (called filamin or Ig-like domains), the 24th of which is responsible for filamin homo-dimerization at the C terminus (Stossel et al., 2001). These 24 Ig filamin repeats of the FLNC protein primarily form a secondary structure of beta strands, as seen in a model of Ig domains 20–21 (Figure 4a) (Sjekloća et al., 2007). The side chain of proline will typically disrupt β-strands due to its unique ring structure (Li, Goto, Williams, & Deber, 1996), and indeed proline 2298 falls in a loop between two such strands (Figure 4b). The change to leucine at this position could disturb this special conformation and lead to protein aggregates. β-rich proteins like FLNC are prone to aggregation, and a leucine substitution could have a higher propensity to form hydrogen bonds between other nearby β-strands which could potentially disrupt protein folding and lead to aggregate formation (Hecht, 1994; Venselaar et al., 2010).

Tyrosine at position 2563 is also evolutionarily conserved across species (Figure 2d), and is located at the end of a β-strand (Figure 4c,d). The mutant cysteine residue is less hydrophobic and smaller than the wild-type tyrosine, and due to its size is predicted to cause an empty space in the protein. The difference in hydrophobicity is also predicted to lead to a loss of hydrogen bonds at the core, which could disturb proper protein folding (Venselaar et al., 2010). In addition to changes to hydrophobicity, the specific tyrosine to cysteine substitution may also be contributing to p.Tyr2563Cys protein aggregation (shown in results below). Substitution of tyrosine and cysteine at key resides of the human α-synuclein protein has been shown to cause accelerated protein aggregation in vitro, likely due to the increased ability for cysteine residues to cross-link and form stable dimers, which could be more prone to polymerization and aggregation (Zhou & Freed, 2004).

3.5 In vitro analysis of FLNC mutants

Previous studies of filaminopathies have shown evidence of mutant FLNC intracellular protein aggregation in both immuno-histological sections of patient muscle and in in vitro transfection of mutant FLNC constructs (Kley et al., 2007; Valdés-Mas et al., 2014; Vorgerd et al., 2005). These aggregates often contain additional Z-disk associated proteins such as desmin, a hallmark of myofibrillar myopathy. In order to determine whether the p.Pro2298Leu and p.Tyr2563Cys variants would also lead to intracellular protein aggregation, full-length wild-type and mutant FLNC-GFP constructs were transiently expressed in C2C12 mouse myoblasts.

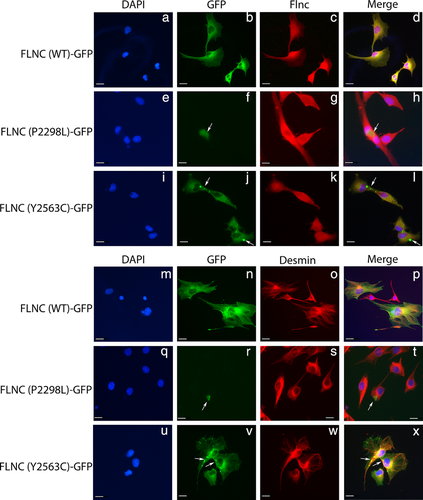

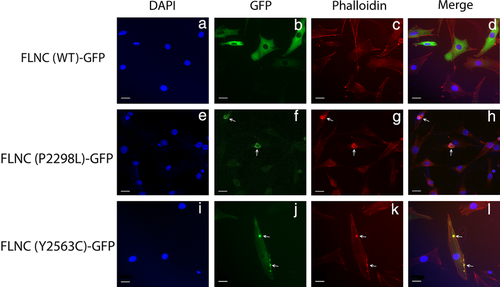

Cells expressing the wild-type FLNC construct exhibited diffuse homogeneous expression of the protein (Figure 5b,n), whereas the p.Pro2298Leu construct yielded aggregates (Figure 5f,r), often near the nucleus. Additionally, the number of cells expressing p.Pro2298Leu mutant protein appeared considerably lower than those expressing the wild-type FLNC construct. Cells expressing the mutant p.Tyr2563Cys construct also demonstrated areas of FLNC aggregation (Figure 5j,v), though these aggregates were punctate and varied in size from small to intermediate. Unlike the results seen with the p.Pro2298Leu construct, the diffuse FLNC expression was not lost in these cells; rather, the p.Tyr2563C aggregates appeared to be randomly distributed throughout otherwise normal protein expression. The pattern of aggregation observed for our p.Tyr2563Cys construct most closely mirrors what has been observed in cells transfected with FLNC variants causing distal myopathy (Duff et al., 2011). Additionally, unlike FLNC variants associated with myofibrillar myopathy, we did not observe the presence of desmin aggregation with mutant FLNC aggregates (Figure 5s,w) or endogenous Flnc co-localizing to exogenous FLNC aggregates (Figure 5g,k).

Given the importance of FLNC as an actin-binding protein, and in vitro data suggesting that FLNC variants may cause actin-aggregation (Kley et al., 2012), we transiently transfected p.Pro2298Leu and p.Tyr2563Cys constructs into C2C12 cells and stained for F-actin. As previously seen, the wild-type FLNC construct showed diffuse cellular expression (Figure 6a–d). The p.Pro2298Leu mutant again resulted in intracellular FLNC aggregates, but these cells also had actin aggregates which appear to co-localize with mutant protein (Figure 6e–h). Taken together, these results suggest the p.Pro2298Leu variant results in an unstable, mutant protein which is prone to aggregation and may contribute to the overall weakening of myofibers as evidenced by actin aggregation. Cells transfected with the p.Tyr2563Cys construct also contained aggregates of both FLNC and F-actin (Figure 6i–l), which again appeared more punctate, and varied in size. Overall, these data suggest the p.Tyr2563Cys is a potentially damaging variant, as it results in aggregates containing both FLNC and F-actin.

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, we described two families with novel FLNC variants as disease causing for RCM: one in a large family with autosomal dominant inheritance and the other in a set of monozygotic, dichorionic/diamniotic twins with extra-cardiac features and a de novo variant. According to the 2015 ACMG variant interpretation guidelines, both variants can be classified as pathogenic. Our evidence to support pathogenicity for p.Pro2298Leu includes: damaging in vitro functional study (PS3); variant found in a mutation hot-spot of CM variants (PM1—see Table 1); variant absent from control databases (PM2); variant segregates with disease in family (PP1); computational evidence supports deleterious effect (PP3); and the patient and family have a disease consistent with a single genetic etiology (PP4). p.Tyr2563Cys is also pathogenic based on the following criteria listed above: PS3, PM1, PM2, PP3, and also a second strong level of evidence; the variant is de novo with maternity and paternity confirmed (PS2). Additionally we do not believe the twins’ compound heterozygous SYNE2 variants explain RCM, although it remains unclear whether they might contribute to some extra-cardiac features. In sum, we have discovered two new pathogenic FLNC variants causing an RCM phenotype.

| Mutation | Domain with mutation | Exon | Mutation type | Phenotype | Disease onset | Number of families/cases associated | Cardiac involvement | Origin of patient(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.Phe106 Leu and p.Arg991Stop | Actin binding (1) and Filamin 8 | 1 and 20 | Compound heterozygous | DCM | Less than 1 year | 1 family with 2 patients | DCM | Ashkenazi | Reinstein et al. (2016) |

| p.Glu108Stop | Actin binding (1) | 1 | Nonsense | HCM | 20–55 years | 1 family with 2 patients | HCM | Spanish | Valdés-Mas et al. 2014 |

| p.Val123Ala | Actin binding (1) | 2 | Missense | HCM | 33–44 years | 1 family with 2 patients | HCM | Spanish | Valdés-Mas et al. 2014 |

| p.Ala193Thr | Actin binding (2) | 2 | Missense | Distal myopathy | 30 years | 1 family with 4 patients | 2 patients with cardiomyopathy | Italian | Duff et al. 2011 |

| p.Met251Thr | Actin binding (2) | 4 | Missense | Distal myopathy | 30 years | 1 family with 9 patients | No | Australian | Duff et al. 2011 |

| p.R269Stop | Filamin 1 | 4 | Nonsense | DCM | 20 years | 1 family with 1 patient | DCM | N/A | Begay et al. 2018 |

| p.Asn290Lys | Filamin 1 | 5 | Missense | HCM | 50 years | 1 family with 1 patient | HCM | Spanish | Valdés-Mas et al. 2014 |

| p.Q707Stop | Filamin 5 | 13 | Nonsense | DCM | 33 years | 1 Family with 1 patient | DCM | N/A | Begay et al. 2018 |

| p.Lys899-Val904delinsValCys | Filamin 7 | 18 | In-frame indel | Myofibrillar myopathy | 35–40 years | 1 family with 10 patients | 5 patients had Cardiac problems starting at 44, 52 and 59 years | Chinese | Luan et al. 2010 |

| p.Val930_Thr933del | Filamin 7 | 18 | In-frame deletion | Myofibrillar myopathy | 34–60 years | 1 family with 2 patients | No | German | Shatunov et al., 2008 |

| c.2930-1G > T | Filamin 8 | Splice site before exon 19 | Splice site | DCM | 39 years | 1 family with 1 patient | DCM | N/A | Begay et al. 2018 |

| p.Ala1183Leu | Filamin 10 | 21 | Missense | RCM with congenital myopathy | RCM at 6 months, neuromuscular involvement at birth | 1 family with 1 patient | RCM | N/A | Kiselev et al. 2018 |

| p.Ala1186Val | Filamin 10 | 21 | Missense | RCM with congenital myopathy | RCM from 6 months to 15 years, neuromuscular involvement at birth or during first year | 3 families with 3 patients | RCM | N/A | Kiselev et al. 2018 |

| p.Tyr1216Asn | Filamin 10 | 21 | Missense | Arrhythmia with late-onset myofibrillar myopathy | N/A | 1 family with 9 patients | Cardiac arrhythmia | French | Avila-Smirnow et al. 2016 |

| c.3791-1 G > C | Filamin 11 | Splice site before exon 22 | Novel splice-site acceptor, 53aa exclusion and frameshift | DCM | 57 years | 1 family with 2 patients | DCM | N/A | Golbus et al. 2014 |

| c.3791-1G > A | Filamin 11 | Splice site before exon 22 | Novel splice-site acceptor, 53aa exclusion and frameshift | DCM | 76 years | 1 family with 1 patient | DCM | N/A | Begay et al. 2018 |

| p.Ala1539Thr | Filamin 13 | 27 | Missense | HCM | 20–82 years | 1 family with 7 patients | HCM | Spanish | Valdés-Mas et al. 2014 |

| p.Ser1624Leu | Filamin 14 | 28 | Missense | RCM | 2–40 years | 1 family with 4 patients | RCM | Caucasian | Brodehl et al. 2016 |

| p.Phe1720LeufsX63 | Filamin 15 | 30 | Frameshift deletion | Distal myopathy | 20–57 years | 3 families with 13 patients | 1 patient has cardiomyopathy | Bulgarian | Guergueltcheva et al. 2011 |

| c.5669-1delG | Filamin 17 | Splice before exon 35 | Splice site | DCM | 46–53 years | 1 family with 2 patients | DCM | USA | Begay et al. 2016 and 2018 |

| p.Arg2133His | Filamin 18 | 39 | Missense | HCM | 25–46 years | 1 family with 2 patients | HCM | Spanish | Valdés-Mas et al. 2014 |

| p.Gly2151Ser | Filamin 19 | 39 | Missense | HCM | 20 years | 1 family with 1 patient | HCM | Spanish | Valdés-Mas et al. 2014 |

| p.Ile2160Phe | Filamin 19 | 39 | Missense | RCM | 10–31 years | 1 family with 6 patients | RCM | Caucasian | Brodehl et al. 2016 |

| p.Val2297Met | Filamin 20 | 41 | Missense | RCM | 14–51 years | 1 family with 8 patients | RCM | N/A | Tucker et al. 2017 |

| p.Pro2298Leu | Filamin 20 | 41 | Missense | RCM | 6–25 years | 1 family with 6 patients | RCM | African American | This study |

| p.His2315Asn | Filamin 21 | 41 | Missense | HCM | 30–73 years | 1 family with 3 patients | HCM | Spanish | Valdés-Mas et al. 2014 |

| c.7251+1G > A | Filamin 22 | Splice after exon 43 | Predicted to remove splice donor for exon 43. | DCM | 27–62 and 20–44 years | 2 families, with 4 and 2 patients | DCM | Italian | Begay et al. 2016 and 2018 |

| p.Thr2419Met | Filamin 22 | 44 | Missense | Myofibrillar myopathy with adult onset cerebellar ataxia | 60 years | 1 sporadic | Mild LV hypertrophy | Italian | Tasca et al. 2012 |

| p.Ala2430Val | Filamin 22 | 44 | Missense | HCM | 25–57 years | 1 family with 3 patients | HCM | Spanish | Valdés-Mas et al. 2014 |

| p.Tyr2563Cys | Filamin 23 | 46 | Missense | RCM | Less than 1 year | 1 family with 2 patients (twins) | RCM | Irish-German/ Polish-German | This study |

| p.Trp2710Stop | Dimerization site | 48 | Nonsense | Myofibrillar myopathy/limb-girdle muscular dystrophy | 37–57 years | 1 family with 17 patients/ 1 family with 7 patients | No | German | Vorgerd et al. 2005 |

| Multiple disease causing candidates | Protein spanning | Multiple | Truncating (stop, frameshift, indels) | Mostly dilated, or arrhythmogenic and few restrictive cardiomyopathies | Less than 1 to 71 years | 28 affected probands and family members | DCM, AVC, RCM | Multiple European ethnicities | Ortiz-Genga et al. 2016 |

| Multiple disease causing candidates | Protein spanning | Multiple | Missense, nonsense | HCM | 21–64 years | 16 affected probands and family members with likely pathogenic or VUS | HCM | Spanish | Gómez et al. 2017 |

- HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; RCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy; LV, left ventricle; AVC, arrhythmogenic ventricular cardiomyopathy; NA, not available. Coding variants in reference to NM_001458.4 FLNC reference sequence.

FLNC is a Z-disk protein which binds to myozenin-1 and myotilin, and its expression is largely restricted to skeletal and cardiac muscles (Linnemann et al., 2010; van der Ven et al., 2006). In addition, FLNC interacts with components of dystrophin-dystroglycan complex at the sarcolemma, thus acting as a scaffolding protein (Thompson et al., 2000). Altogether, Filamins interact with more than 90 cellular proteins with diverse functions including cell to cell and cell matrix connections, mechanoprotection, and various signaling networks (Feng & Walsh, 2004; Razinia, Mäkelä, Ylänne, & Calderwood, 2012). Recent data by Leber et al. (2016) show evidence of FLNC as a key early protein involved in myofibril repair for both skeletal and cardiac muscle cells. Their work suggests FLNC may be more of a mobile signaling hub rather than a largely structural and static protein (Leber et al., 2016). The early onset of RCM in the presented families suggests the importance of FLNC expression and its role in heart function.

FLNC variants are a recently recognized cause of phenotypically distinct cardiomyopathies including HCM, DCM, and RCM (Begay et al., 2016; Brodehl et al., 2016; Valdés-Mas et al., 2014). FLNC-related cardiomyopathies present a challenge in extrapolating genotype-phenotype correlations based on variant position (Table 1). Valdés-Mas et al. (2014) identified eight HCM variants of which two are located in the actin binding domain, while the other six are distributed throughout the 24 filamin Ig domains. Interestingly, five of these six variants are located in C-terminal half of the protein and four are notably clustered in filamin repeats 18–22. A larger cohort of HCM patients sequenced by the same group identified additional candidate FLNC variants as potentially disease causing, most of which fell in the latter half of the protein (Gómez et al., 2017). Of interest, one likely pathogenic variant identified by Gómez et al. (2017) was at the same residue position (p.Pro2298Ser) as the variant reported here in family 1 (p.Pro2298Leu). The pattern of HCM variants falling in the C-terminal half of the protein is also seen with RCM variants: the two we report here fall in filamin repeats 20 and 23, a neighboring RCM variant to p.Pro2298Leu (p.Val2297Met) was recently reported by Tucker et al. (2017), and variants published by Brodehl et al. (2016) localize in repeats 14 and 19.

FLNC variants causing DCM have the most direct evidence of a genotype–phenotype relationship. Of the eight previously reported DCM variants, five are splice site variants (Begay et al., 2016; Begay et al., 2018; Golbus et al., 2014), while three are nonsense variants resulting in an early protein truncation (Begay et al., 2018; Reinstein et al., 2016). Genetic screening of large DCM patient cohorts revealed an association with truncating FLNC variants (stop codons, frameshifts, and splice site variants), strongly suggesting an overlap between mutational mechanisms and patient phenotype (Janin et al., 2017; Ortiz-Genga et al., 2016). Until recently, skeletal myopathy and CM-causing FLNC variants have been reported to cause isolated phenotypes in their respective tissues. Interestingly, however, a new publication has described disease-causing FLNC variants leading to both early-onset RCM and the skeletal muscle phenotypes congenital myopathy and clasped thumbs (Kiselev et al., 2018). The patients described here showed no evidence of myopathy on repeated exams although the twins did exhibit hypotonia. In light of the report by Kiselev et al. (2018), it is possible the p.Tyr2563Cys variant could be contributing to the twins’ observed skeletal muscle phenotypes (hyoptonia and clasped thumbs), although this variant is not near the two variants Kiselev et al. (2018) found (p.Ala1183Leu and p.Ala1186Val). However, we do not believe the twins’ other syndromic-like phenotypes, such as developmental delay and dysmorphic facial features, can likely be explained by a FLNC variant alone, and those hint at the possibility of a second underlying disorder. Additional functional studies will be necessary to determine the FLNC variant-specific effects resulting in isolated skeletal or heart muscle disease, or those which affect both tissues. In addition, mechanisms to explain the divergent cardiac phenotypes resulting from distinct FLNC variants remain to be elucidated.

Functional and structural analyses suggest that FLNC-mutants recruit FLNC-associated proteins to form aggregates, leading to destabilization of muscle tissue (Lowe et al., 2007; Luan, Hong, Zhang, Wang, & Yuan, 2010). Abnormal accumulations of FLNC deposits in patients’ muscle tissues have been reported in a number of neuromuscular diseases (Bönnemann et al., 2003; Sewry et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 2000). In vitro analyses for mutant FLNC p.Pro2298Leu revealed formation of perinuclear intracellular aggregates, while p.Tyr2563Cys expressing cells also formed point aggregates containing FLNC and F-actin, confirming the likely pathogenicity of these variants. Of note, similar experiments for HCM, DCM, and RCM FLNC mutants also resulted in aggregations of mutant protein, many of which shared a similar pattern of aggregate expression around the nucleus (Brodehl et al., 2016, Reinstein et al., 2016; Valdés-Mas et al., 2014). The exact mechanism for this aggregate-based pathogenicity is unknown, but this could be an error in ubiquitination and lysosomal-dependent degradation of mutant FLNC as well as of other members of filamins.

Changes in filamin structure initiate the binding of the co-chaperone BAG3 as well as the ubiquitin ligase CHIP. CHIP ubiquitinates BAG3 and filamin leading to autophagy by the p62 pathway (Arndt et al., 2010). Recent data suggest aggregates produced by the filamin C p.Trp2710X MFM variant in zebrafish were unable to be cleared properly by BAG3 and the chaperone assisted selective autophagy pathway (Ruparelia, Oorschot, Ramm, & Bryson-Richardson, 2016). Additionally, they noted the presence of BAG3 at these aggregates hindered alternative pathways that might have been able to remove them. Further studies of FLNC-aggregates produced by a wide range of variants are needed in order to elucidate the mechanisms by which these aggregates persist, and to develop potential methods to clear them.

In summary, we identified two novel FLNC missense variants causing a distinct RCM phenotype in two families, and further demonstrated these variants lead to protein localization defects in vitro. This study provides new variants and additional evidence for the wide spectrum of currently known FLNC variants, and bolsters support for the inclusion of FLNC in genetic testing of CM patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of both families who participated in this study. We thank Maria Padua for a critical reading of the manuscript.