The performance impact of gender diversity in the top management team and board of directors: A multiteam systems approach

Orlando C. Richard and María del Carmen Triana contributed equally to this study.

Abstract

Given the mixed evidence that having both women and men in the top management team (TMT) or in the board of directors (BOD) has a significant influence on organizational innovation, we resolve this issue by conceptualizing TMT–BOD gender diversity as part of a multiteam system, that has joint effects which impact organizational innovation. Evidence from the study of both Chinese firms and UK firms confirm our conceptualization by showing an interaction effect between TMT gender diversity and BOD gender diversity such that innovation is greatest when both are high. The positive TMT–BOD gender diversity interaction effect on innovation improves subsequent firm performance particularly in dynamic environments. The findings refine current thinking by going beyond research that tests intra-team TMT or BOD diversity independently and instead considers inter-team diversity across both leadership teams within the strategic leadership upper echelons. In sum, findings show that high levels of TMT and BOD gender diversity result in more organizational innovation, which ultimately improves firm performance. We offer implications for women's inclusion in leadership as well as for research on the upper echelons.

1 INTRODUCTION

The most important human resource decision a firm will ever make is who will govern the firm (Boxall, 1996). A firm's leadership team, meaning the board of directors (BODs) and top management team (TMT), unquestionably occupies a position of central prominence in human resource management (HRM). However, two principal and largely disconnected research streams have emerged to study diversity in BODs and TMTs. One line of thought in the BOD diversity literature has focused on demographic composition, specifically gender composition, to assess whether gender diversity in the upper echelons impacts organizational effectiveness (Dezsö & Ross, 2012; Hoobler et al., 2018; Post & Byron, 2015). Evidence of how gender diversity affects firm innovation and performance is often rooted in social identity theory (Hogg & Abrams, 1988) and social categorization theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), which propose that members in a team compare themselves with others and classify themselves into social categories using salient characteristics such a gender. Through this process, members are likely to have ingroup favoritism and outgroup discrimination (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Turner et al., 1987). In this literature, gender diversity is typically characterized by potential conflicting values and beliefs, increased within-group communication, and reduced cross-group communication, which results in more intergroup conflict (Milliken & Martins, 1996). In contrast, other scholars provide a different and more optimistic line of thought. According to this point of view, rooted in the information-processing perspective (Gruenfeld et al., 1996; Phillips et al., 2004), high levels of gender diversity provide a broad range of knowledge, experience, information, and diverse problem-solving perspectives that stimulate careful analyses of problems (Gibson & Vermeulen, 2003; Homan et al., 2007). Low levels of diversity, in contrast, are likely to lead to redundant information due to homogenous knowledge, experiences, and information among a group of actors (Jehn et al., 1999; Webber & Donahue, 2001). A more recent study, for example, found that following female (but not male) appointments into the TMT, TMT cognitions move toward more of a change orientation that subsequently increases research and development (R&D) activities (Post et al., in press). Despite substantial efforts of the two aforementioned research streams, the effects of gender diversity (e.g., some positive, some negative; Joshi & Roh, 2009) still remain unclear, and research on diversity in the upper echelons has been criticized for its overwhelming focus on either BODs or TMTs without considering dependencies on the other leadership/governance team (Dalton et al., 2007).

A few scholars have tried to advance theory on strategic leadership teams by simultaneously considering both the TMT and the BOD (Kor, 2006; Luciano et al., 2020). In this study, we draw on the insights from both TMT and BOD research but go beyond them to examine the joint impact of TMT and BOD gender diversity to explain organizational innovation. While extant literature provides a theoretical framework for TMT–BOD interactions (Luciano et al., 2020), research conceptualizing TMTs and BODs as a multiteam system has been (at most) preliminary for two reasons. First, neither conceptualization nor empirical evidence has been crystalized with respect to whether and to what extent (a high vs. low degree of) environmental dynamism influences the joint effect of TMTs and BODs. Research in organizational studies purports that investigating human capital dynamics without considering the environmental influences only provides incremental contributions, whereas a contingency based framework offers more novel theoretical implications (Delery & Doty, 1996; Johns, 2006; S. Lee, 2021; Richard et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2021). Second, research has not theoretically considered, let alone empirically tested, innovation consequences of examining both the TMT and BOD simultaneously. Therefore, this important framework is uncertain, necessitating deeper theoretical development and empirical testing. In this study, we address these two weaknesses. On the one hand, we investigate the joint impact of TMT and BOD gender diversity to explain organizational innovation. We develop a theory on how a key environmental facet (i.e., dynamism) strengthens or weakens the influence of two strategic leadership teams working interdependently to achieve organizational innovation and test these ideas in two samples. On the other hand, we conceptualize innovation as an intervening variable linking gender heterogeneity in the upper echelons to firm performance (Lawrence, 1997). We further examine whether TMT gender diversity interacts with BOD gender diversity to bolster organizational innovation when a firm competes within a dynamic environment.

In doing so, we make important theoretical contributions to two mostly separate streams of research on TMTs and BODs. We contribute to the gender and diversity literature by theoretically studying tenets of upper echelons theory (Hambrick & Mason, 1984) within a multiteam systems framework to explain why high gender heterogeneity in both the TMT and the BOD has greater capacity to result in organizational innovation compared to low gender heterogeneity in one or both of these entities. Previous research has explored the role of the TMT or the BOD and how contingency factors moderate their effects on organizational outcomes (e.g., Cannella et al., 2008; Qian et al., 2013; Triana et al., 2014; Wiersema & Bantel, 1992), but prior studies did not consider all members of the upper echelons who are charged with strategic decision-making. Our theoretical approach to the question “What is the organizational innovation impact of simultaneously including women on both the TMT and the BOD?” has significant implications for scholarly inquiry. For instance, how can the BOD benefit from gender diversity in its relation to the TMT, in turn enabling organizations to develop the variety of perspectives that today's corporate world demands (Miller & Triana, 2009)? This study also makes important contributions to the strategic leadership system literature. We answer calls for research that jointly examines TMTs and BODs and considers boundary conditions such as environmental dynamism (Luciano et al., 2020). Importantly, we go beyond Luciano et al.'s (2020) theory paper by providing empirical evidence, which is essential to test and refine theory.

We contribute a more concrete conceptual model of gender diversity in strategic leadership teams that is applicable across national context. To establish generalizability, we collected samples from China and the United Kingdom to test our conceptual model. China provides an ideal context for several theoretical reasons. First, environment dynamism has been conceptualized as market instability and as a lack of predictability among stakeholder relationships (between customers, suppliers, regulatory agencies, and competitors) (Keats & Hitt, 1988; C. C. Miller et al., 2006). China presents a unique context for a multiteam system framework, since it is a highly dynamic environment characterized by ambiguity in means–ends relationships (Siggelkow & Rivkin, 2005) that spurs the need for interdependence between the BOD and TMT to align goals and govern the firm. Second, China experiences patterns of environmental change due to economic reformation and institutional transition coupled with Chinese governmental changes in regulatory policies, rapid changes in customer preferences (Barkema et al., 2015), and trade wars with major Western countries. A highly dynamic environment demands Chinese firms recognize the value of BODs and TMTs working interdependently so they may outcompete rivals within uncertain environmental contexts (Luo & Peng, 1999). One consequence of institutional and environmental changes is less gender parity in China (Post & Byron, 2015) which, coupled with a demand for women in both the TMT and the BOD, makes the country a suitable context to test our hypotheses (Wu et al., 2021). Third, encouraged by the Chinese government's aspirations to enhance China's national innovation capacity, Chinese firms (e.g., Huawei, Tiktok) have been very proactive in acquiring and developing new skills and technologies. The highly dynamic environment, growing women's representation in leadership and corporate governance, and the innovative performance of Chinese firms makes China ideal to test our hypotheses.

We further test our gender diversity in strategic leadership teams model in the United Kingdom, due to both theoretical and empirical reasons. First, unlike China, which has a combination of state-owned and privately-owned firms, companies in the United Kingdom are all privately-owned, which may give the TMT and BOD more managerial discretion. When it comes to making strategic decisions, those firms with gender diversity (i.e., more women representation) may likely foster innovation capabilities (Miller & Triana, 2009). Second, recent research of UK firms unveils a positive association between female representation on BODs and intellectual capital efficiency, comprised of human capital, structural/innovation capital, and financial capital efficiency (Nadeem et al., 2019). This literature hints that strategic leadership team dynamics, which account not only for the BOD but also the TMT, have critical implications for firm innovation and performance. The present study of UK firms together with Chinese firms will lend insight to this critical point in the literature. Third, some studies emphasize that countries with high shareholder protection can benefit from gender diversity due to improved decision-making (Post & Byron, 2015). The present study introduces more nuanced theorizing to the study of the upper echelons across two important countries in the world (China and the United Kingdom). The consistent results support the insight that gender diversity of both TMT and BOD has a positive effect on organizational innovation. In sum, this research contributes to theory on gender diversity in the executive suites and strategic leadership teams.

2 THEORY AND HYPOTHESES

Historically, the “Think Manager, Think Male” philosophy explained the lack of women in the upper echelons (Schein, 1973, 2007), but in this new era where #MeToo has illustrated gender inequality, companies are being more proactive in promoting women into the executive ranks (Catalyst, 2020). Partly due to the mounting evidence showing that the “glass ceiling” which impedes women's progress toward executive positions hurts the organization's bottom line due to women's untapped human capital (Baxter & Wright, 2000; Catalyst, 2020), we investigate gender diversity in upper echelons as women worldwide slowly make inroads into positions in firms' top management teams as well as directorships (Catalyst, 2020; Lyngsie & Foss, 2017). Indeed, these trends toward increased gender diversity (i.e., heterogeneity) amplified by social movements (e.g., #MeToo) motivate practitioners and scholars to analyze how the representation of women in historically male-dominated leadership settings impacts organizational success (Joshi et al., 2011).

Our central question is: “How does gender diversity among strategic leadership using a multiteam perspective affect innovation?” The diversity literature has associated gender diversity with negative outcomes such as relationship conflict (Jehn et al., 1999) and lower cohesion (Webber & Donahue, 2001), as well as with positive outcomes such as enhanced creativity, improved problem-solving, high-quality decisions, and corporate social responsibility (Cox & Blake, 1991; Macaulay et al., 2019; van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). On the one hand, gender diversity provides the team a broader range of knowledge which improves innovation (Triandis et al., 1965; Wu et al., 2021) and decisions (Mintzberg et al., 1976). For example, in the identification phase, gender diversity on the board helps identify new innovative opportunities (Miller & Triana, 2009). Because of the broad range of knowledge, a diverse group also has a greater variety of ideas and perspectives as it searches for and designs solutions in the development stage, which allows for a more thorough evaluation of choices in the selection stage (Phillips et al., 2004). Such explanations are grounded in empirical findings, as research has shown that having women in management results in the launch of new products or services (Lyngsie & Foss, 2017) and management innovation (Heyden et al., 2018). Furthermore, gender diversity provides nonredundant ties engaging in interactions which help executives to overcome decision biases and improve the quality of decisions. Members in a diverse group tend to have different social capital and network resources (Daft & Lengel, 1984; O'Reilly, 1983) which offer greater, more diverse (Ibarra, 1992, 1993) and nonredundant information that can spur innovation (Miller & Triana, 2009). In sum, the importance of a broad range of nonredundant knowledge, ideas, and perspectives shared by a diverse group (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004) is endorsed by studies taking the information-processing perspective.

On the other hand, the negative influences of gender diversity are rooted in intergroup differences and conflicting values and beliefs across groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). For example, diversity of information comes at a cost since the decision-making process can take longer when more information is present (Watson et al., 1993). The volume of viewpoints considered by a gender-diverse team may result in a longer and slower decision-making process (Cox et al., 1991). Moreover, due to potential heterogeneous cognition, and conflicting values and beliefs among executives, a gender-diverse team could impede communications across groups and lead to intergroup conflict (Jehn et al., 1999), which hinders the ability to reach consensus and restricts the ability to generate new ideas (Triana et al., 2014).

The logic proposing the advantages of gender diversity is used to explain information-processing and creativity, while the perspective proposing disadvantages is used mostly to describe intergroup conflict that reduces innovation (Chua & Jin, 2020). Research in gender diversity typically uses one of the two arguments and relates diversity to risk-taking orientation along an entire performance spectrum (Miller & Triana, 2009; Richard et al., 2019; Triana et al., 2014), but very few efforts have been made to integrate the two arguments which might be more suitable for between-team predictions (i.e., TMT vs. BOD). Moreover, a weakness in existing gender diversity theory concerns an inattention to the gender diversity of other closely related groups (i.e., the interplay between the TMT and BOD).

Without doubt, the gender diversity literature that contains a double-edged sword resulting in both disadvantages and advantages (Giambatista & Bhappu, 2010; Hoffman, 1959; Kilduff et al., 2000; Milliken & Martins, 1996) is an important basis for us to develop explanations for the effects of gender diversity in strategic leadership on firm innovation. However, we depart from literature that focuses on one strategic leadership team without the other, because that results in a piecemeal approach to understanding the impact of upper echelons demography, which could result in an incomplete understanding of how gender diversity within strategic leadership impacts organizational innovation. We propose a synergistic joint TMT to BOD effect, where having more gender diversity in both the TMT and BOD provides a greater pool of knowledge-based resources. Therein, a shared understanding between a gender-diverse TMT and a gender-diverse BOD will allow for more effective knowledge exchange and integration of ideas around issues, which is beneficial to increase organizational innovation.

We draw on the strategic leadership system multiteam perspective (Luciano et al., 2020) which offers two important solutions for determining the relationship between upper echelons gender diversity and organizational performance. First, rather than treating the TMT and BOD as two distinct and independent bodies having only independent effects (consistent with agency theory assumptions; Daily et al., 2003), these scholars offer a multiteam systems framework where the TMT and BOD comprise a strategic-oriented multiteam system. By simultaneously emphasizing the dependence and interdependence between the TMT and BOD, this strategic leadership system affords the opportunity to more holistic theoretical predictions pertaining to the upper echelons (Luciano et al., 2020). Second, embracing an open systems view that firms operate in complex and dynamic environments, scholars have argued that environmental turbulence influences attention to working independently or interdependently on multiteam system effectiveness (Luciano et al., 2020; Zaccaro et al., 2012). Accordingly, Luciano et al. (2020) state that, compared to more stable and predictable external environments, the pressure to attend to working independently and interdependently may shift in a changing, turbulent environment.

We draw on this multiteam systems framework but we substantially advance it in three essential ways. First, combining the fact that (a) the TMT affects organizational strategic decision-making (Hambrick & Mason, 1984) and (b) boards influence innovation given their power to not only control and monitor the TMT but also to influence TMT strategic decision-making (Deutsch, 2005; Triana et al., 2014; Westphal & Fredrickson, 2001), we suggest that innovation should play a key role in the multiteam systems framework. For example, Luciano et al. (2020) speculate (with some doubt) that the board's input may yield more innovative actions but also slow decision-making which can result in missing opportunities. We contribute to the multiteam system research by explicitly proposing that innovation at the organizational level is governed by the joint effect of the TMT and the BOD. Second, the multiteam systems perspective acknowledges that a dynamic environment will push TMTs and BODs to coordinate efforts to overcome challenges associated with information-processing, but this has not been empirically tested. In this study, we theoretically clarify and empirically test how environmental dynamism changes the effect of TMT–BOD gender diversity on organizational innovation and distal firm performance, thereby testing and extending the multiteam systems perspective of strategic leadership. Third, while a key assumption of the multiteam strategic leadership perspective is “the temporal and conceptual distinction between proximal and distal outcomes” (Luciano et al., 2020, p. 678), to our knowledge this has not yet been tested in a multiteam strategic leadership study. To that end, we investigate how TMT–BOD gender diversity (year t) affects proximal organizational innovation (year t + 1) and distal firm performance (year t + 2) and how proximal organizational innovation mediates the effect of TMT–BOD gender diversity on distal firm performance. These three important contributions are illustrated by the theoretical developments for Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and are further corroborated by rigorous empirical tests in samples from China and the United Kingdom.

2.1 TMT–board intergroup interactions and innovation

When both TMT and BOD gender diversity are low, we predict less organizational innovation (Miller & Triana, 2009; Triandis et al., 1965), because the underrepresented members' voices and opinions in both TMT and BOD often times are not considered by the overrepresented members (Kanter, 1977; Ridgeway, 2011, 2014). Such difficulty communicating across demographic subgroups is known to be an issue for upper echelons demographic diversity (Ancona & Caldwell, 1992). The same communication issue may even be magnified when gender diversity in both the TMT and BOD are low. For example, a homogenous TMT tends to prefer investment projects that build on familiar concepts, ideas, and technologies, and is reluctant to pursue projects that build on new knowledge or change the firm's strategic direction (Ahuja & Lampert, 2001). Such rigid ideas can be furthered by a homogenous BOD, because the latter's low receptivity toward new investments limits its ability to recognize the value of new initiatives (Cox & Blake, 1991; Hambrick & Mason, 1984), reducing organizational innovation. Therefore, we expect the lowest level of innovation to be present when gender diversity is low within the entire strategic leadership team (i.e., both TMT and BOD).

When either TMT or BOD gender diversity is low in one group while high in the other, potential information-sharing benefits offered by a diverse group are likely to be poorly utilized by the group with homogenous members. For example, when the TMT is gender-diverse but the BOD is gender-homogenous, ideas coming from the TMT may be discouraged by the BOD in its advice-giving capacity if the board does not share the same perspective. Also, a gender-diverse TMT may propose innovations that are unrelated to the prior knowledge and experiences of gender homogenous BODs (R. J. Ely & Thomas, 2001). In a study about TMTs and chief executive officers (CEOs), Georgakakis et al. (2017) demonstrated that some level of demographic background and/or experience similarity between two different entities in the upper echelons facilitates understanding between those organizational members at different organizational levels. Compared to TMTs high in gender diversity, TMTs with low gender diversity are more likely to have a similar body of knowledge and perspectives (Byrne, 1971). In such cases, TMTs are less likely to search for, grasp, and consider innovative ideas presented by a gender-diversity BOD and are more likely to hold on to their established mental model of how things should be done (Thompson, 2018). Homogenous TMTs are more likely to overlook potential opportunities generated in mutual exchanges with gender-diverse BODs, which could provide sources of unconventional thinking and innovation.

By the same token, a gender-homogeneous BOD may not possess either a broad enough knowledge base or a diverse enough network of contacts to support frequent TMT innovative initiatives (Ibarra, 1992, 1993). Although a gender heterogeneous TMT might be open to and more likely to initiate innovation, a gender homogeneous BOD would prefer less proactive strategic behavior and change. Similarly, when TMT gender diversity is low, the TMT will be less receptive toward implementing organizational innovations that a gender-diverse BOD suggests. Although strategy is primarily formulated by the TMT, the BOD does serve in an advisory and resource provision capacity (Johnson et al., 1996) which also shapes strategy (Deutsch, 2005). Even if board members present multiple perspectives and suggestions in their advice role, these potential innovations may fall on deaf ears in the TMT if the TMT is not open to such innovations.

In contrast, when high TMT–BOD diversity is present, this abundance of perspectives will amplify the knowledge benefits, thereby overshadowing the potential for conflict and communication difficulties (Ancona & Caldwell, 1992), resulting in more innovation (Gruenfeld et al., 1996; Phillips et al., 2004). A gender-diverse BOD is more likely to approve a variety of strategic proposals put forward by the TMT if the BOD has a broader knowledge base and is more flexible in its own thinking (Cox & Blake, 1991; Goodstein et al., 1994; Post & Byron, 2015; Ruderman et al., 2002; Ward & Forker, 2017). The resource provision function of boards involves activities such as providing legitimacy, expertise, advice, counsel, information, and other resources to firm executives, which can facilitate innovation (Johnson et al., 1996). Different genders provide a range of experiences, perspectives, and social resources that can enhance the firm's ability to innovate (Miller & Triana, 2009).

Access to diverse resources via gender-diverse BODs is especially important for gender-diverse TMTs. Diverse management groups have an increased need for external resources in order to support intensive competitive activity (Andrevski et al., 2014), since they generate a variety of new competitive moves. As such, a gender-heterogeneous TMT can integrate a gender-diverse BOD's knowledge and use these connections to provide a competitive advantage (Barney et al., 2001). While gender heterogeneous TMTs might be equipped to acquire and accumulate various resources, the BOD can have a notable impact on the TMT's priorities by ensuring they stay knowledgeable regarding the industry, competition, and strategic options (Zahra et al., 2009). Gender-diverse BODs are therefore more likely to complement and expand the TMT's innovative capacity by providing access to external resources. BOD diversity can generate ideas for new strategic actions and provide resources supporting the TMT's innovative actions (Carpenter et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2009).

Furthermore, if gender diversity is high on both the TMT and the BOD, then there will be more women represented in the upper echelons and it will be normative to involve women in strategic decision-making. Research on board gender diversity shows that when women reach a critical mass of three or more women on the board, firms are more innovative (Torchia et al., 2011). Having high gender diversity on both the TMT and the BOD makes it more likely that the upper echelons has a critical mass of women, which can bolster innovation. A gender-diverse BOD can then encourage the TMT to explore various options because they are willing to embrace those options. A gender-diverse TMT would be more likely to accept alternative perspectives from a gender-diverse BOD, which would enhance rather than simply echo the TMT's voice. In sum, we suggest that high gender diversity on both the TMT and BOD amplifies the advantages and mitigates the disadvantages of gender diversity, resulting in more innovation. We predict that a gender diverse TMT is more likely to echo a gender diverse BOD as both teams are more likely to introduce new ideas, perspectives, and knowledge. The BOD will also be better able to leverage the TMT's innovative capacity by providing a wide range of knowledge-based resources.

Hypothesis 1.TMT–BOD gender diversity (i.e., high gender diversity in both TMT and BOD) has a positive effect on organizational innovation.

2.2 The moderating role of environmental dynamism

Research highlights that more stable environments constrain strategic decision-making processes (Yamak et al., 2014), while dynamic environments demand a broader range of knowledge from TMTs and BODs in order to handle ever-changing situations (Gordon et al., 2000). We propose that TMTs and BODs will share an overarching goal for more organizational innovation in a dynamic environment, because the context demands that for firm competitiveness (Luciano et al., 2020; Zaccaro et al., 2012). In a volatile environment, it is important for the firm to possess diverse perspectives and have the capability to integrate knowledge across members of the strategic leadership team (Judge & Miller, 1991). Therefore, in a dynamic environment, we expect the TMT and BOD will benefit from gender diversity and from more interdependent rather than independent work which will ultimately maximize innovation. Hence, we propose that the positive effect of TMT–BOD gender diversity on innovation is moderated by environmental dynamism such that a gender heterogeneous TMT in conjunction with a gender heterogeneous BOD will be more willing to undertake necessary innovative changes in dynamic environments than stable ones for the following reasons.

First, the benefits associated with gender diversity-based knowledge contained within the TMT–BOD match will be stimulated by a dynamic environment. A dynamic environment motivates members of TMTs and BODs to adopt a coherent and consistent schema for strategic action to achieve continuous innovation (Gordon et al., 2000; Rajagopalan & Spreitzer, 1997). As such, both the TMT and BOD should be more proactive and cooperative regarding strategic actions. A wealth of useful information offered by TMT–BOD gender diversity is useful for innovative initiatives and more likely to be obtained when cooperation and coordination are high, which we argue, will be most demanded in a dynamic environment compared to a stable environment. This is consistent with the theory by Luciano et al. (2020), who stated that dynamic environments require rapid responses and realignments that necessitate strong interdependence between the TMT and the BOD while also maintaining BOD independence required for good governance. In stable environments, a broad range of knowledge is less necessary, because while BOD and TMT members may possess diverse perspectives based on their gender differences, they are less motivated to work together interdependently. A dynamic environment will provide a context that demands greater coordination, and when both the TMT and the BOD possess gender diversity-based information, the two teams may be better equipped to innovate.

Second, a dynamic environment requires more creative decision-making than a stable environment (Hambrick et al., 2015; Hambrick & Mason, 1984), which stimulates the information-sharing benefits of diverse groups. In dynamic environments, gender diversity should be seen as an opportunity rather than a threat, because of the need for innovation. Further, research on team dynamics shows that when diverse teams approach their work with the mindset that diversity is an advantage, the teams perform better (Homan et al., 2007, 2008). Research demonstrates that the need for knowledge-based assets that heterogeneous TMTs and BODs possess is indeed evident within dynamic environmental contexts (Cannella et al., 2008). The gender diverse nature of the TMT and the BOD joint influence is amplified by the dynamic environmental context, which will trigger more of a need for TMT–BOD intergroup interdependence through improved coordination/cooperation (Cooper et al., 2014; Luciano et al., 2020) and a greater demand for innovative outcomes. In environments that are stable rather than dynamic, we expect less impetus for TMT–BOD coordination and less emphasis on maximizing innovation efforts, especially if either (or both) the TMT and BOD are also low on gender diversity. In sum, because dynamic environments require more creativity from strategic leadership teams to meet the demands for greater innovation needed for competitiveness, we propose a gender-diverse TMT will (a) be better able to coordinate with a gender diverse BOD, and (b) be better equipped to contribute interdependently with a gender diverse BOD.

Hypothesis 2.The positive effect of TMT–BOD gender diversity on innovation is moderated by environmental dynamism such that the effect is stronger in dynamic environments than in stable ones.

2.3 The mediating role of innovation

Hypothesis 2 suggests that the positive effect of TMT–BOD gender diversity fit on innovation is moderated by environmental dynamism. We move beyond that prediction by examining mediation and considering a mechanism that links intergroup TMT–BOD gender diversity to firm performance (Hoobler et al., 2018; Lawrence, 1997). We focus on the role of innovation as the mediating mechanism between the interaction of TMT–BOD gender diversity and environmental dynamism on firm performance.

Our reasoning is that innovation can transmit the interactive effect of the benefits associated with high TMT–BOD gender diversity and environmental dynamism to firm performance. This is because innovation modifies a firm's current market status, preventing the organization from entering an inflexible state of inertia (Klarner & Raisch, 2013; Levinthal & March, 1993). In this sense, innovation can be viewed as continuous change and adjustments by a focal firm in order to outperform its rivals (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997). Although innovations do not always result in better firm performance, firms making purposeful changes are more likely to have better performance than those firms that do not (D. Miller, 1991). As such, the innovation benefits accrued from gender diversity in both TMT and BOD should ultimately result in better performance, particularly in dynamic environments.

Taken together, we propose a comprehensive moderated mediation model such that the positive joint effect of TMT gender diversity and BOD gender diversity within our multiteam system framework has an indirect effect on firm performance via innovation. This TMT gender diversity-BOD gender diversity positive interaction effect will be more salient in a dynamic environment because (a) coordination between the TMT and BOD will be possible with both having gender diversity (Georgakakis et al., 2017), and (b) creativity will be maximized because both the TMT and the BOD will seek to utilize their knowledge bases to meet the superordinate goal of increasing organization innovation (Sherif, 1966). In contrast, in a stable environment where innovation is often not a prerequisite for long-term competitiveness, we posit that TMT to BOD gender diversity within the multiteam system results in less coordination between the TMT and BOD and fewer innovative outputs based on additive independent effects of the TMT or the BOD rather than multiplicative interdependent effects, both of which diminish organizational innovation and subsequent firm performance. The following prediction is made:

Hypothesis 3.The interactive effect of TMT–BOD gender diversity and environmental dynamism on firm performance is mediated by innovation.

3 STUDY 1 METHOD

3.1 Data and sample

We test our hypotheses by constructing panel data on the TMTs and boards of publicly listed Chinese companies from multiple sources. Publicly listed Chinese companies are posted on both the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. We extracted TMT and board characteristics (e.g., gender) from the Corporate Governance Database provided by the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database, a prominent provider of data from publicly listed Chinese firms. We extracted firm-level financial information and other data (e.g., R&D expenditure, number of employees and ownership structure) from the annual reports of each publicly listed Chinese company. We then matched different databases based on a unique stock code identifier. The final sample contained 944 firm-year observations consisting of 328 firms from 2008 to 2013.

3.2 Dependent variables

3.2.1 Innovation (time t + 1)

Previous literature has established that a firm's R&D expenditures are an appropriate indicator of the firm's innovation, because R&D expenditures reflect decisions made by directors to allocate critical resources to innovate (Balkin et al., 2000; Hitt et al., 1997; Hoskisson et al., 2002). Moreover, some gender and diversity studies have used R&D intensity to investigate the effects of board diversity on firm innovation (Miller & Triana, 2009). Although R&D intensity is only one important proxy for innovation, it has been established as an appropriate and objective proxy by previous researchers (Balkin et al., 2000; Hitt et al., 1997), notably in the manufacturing industries, and it is a relevant measure for the empirical study of the manufacturing companies reported in this article (Miller & Triana, 2009). Therefore, we followed this stream of research and measured innovation using R&D intensity, which was operationalized by dividing a firm's reported R&D expenditures by sales. This variable was analyzed at time t + 1.

3.2.2 Firm performance (time t + 2)

We measured firm performance using Tobin's Q, which was calculated by a company's market value divided by the difference among its total assets, net intangible assets, and net goodwill (K. H. Chung & Pruitt, 1994; D. E. Lee & Tompkins, 1999). We extracted these variables for each sampled firm from the CSMAR's Corporate Financial Index Analysis Sub-Database in order to calculate Tobin's Q. This measure of Tobin's Q has been shown to be a very good proxy that is consistent with the other measures of Tobin's Q such as those proposed by D. E. Lee and Tompkins in 1999. To test Hypothesis 3 regarding the mediating effect of innovation on firm performance, we measured Tobin's Q at year t + 2 to lag it 1 year after the mediator, innovation at year t + 1 (Richard et al., 2007).

3.3 Independent variables

3.3.1 TMT gender diversity (time t)

We define TMT membership broadly by considering the CEO and senior executives to be TMT members if the latter directly report to the CEO and are responsible for making strategic choices. On average, senior executives who fall into these categories within our sample consist of seven TMT members over the course of a given year. This is consistent with Guadalupe et al.'s (2013) finding that the size of TMTs has increased in many companies over the last three decades due to an increase in the number of various functional directors who report directly to the CEO. In the sampled TMTs, 89% of the TMT members were male and 11% were female. Consistent with Kanter's tokenism theory (1977), which makes predictions depending upon the ratio of women on boards and the number of women on boards, we measure TMT gender diversity as TMT Women Ratio (computed as the number of women on the TMT divided by the total number of people on the TMT).

3.3.2 Board gender diversity (time t)

We define directors as the board members sitting on the BOD. Such directors include the president of a board, the vice president of a board and executive directors. In our sample, 90% of the board members were male and 10% were female. We measure board gender diversity as the Board Women Ratio.

In a post hoc robustness check, we used two additional measures of diversity. The first measure is number of women (TMT Women Number and BOD Women Number), because it is a similar measurement to women ratio. The second measure is Blau's (1977) index of heterogeneity (TMT Gender Heterogeneity and BOD Gender Heterogeneity). Blau's index is commonly used to measure diversity on a categorical variable such as gender (Bantel & Jackson, 1989; Triana et al., 2014). Specifically, TMT gender diversity =  in which

in which  is the proportion of TMT group members sorted into separate male and female categories. The Blau's index reflects a variety-based measure of diversity or variability and is used to obtain a relative measure of heterogeneity that is not skewed in favor of either gender (Harrison & Klein, 2007). For TMT gender diversity, Blau's (1977) index ranges from 0 (when only one gender is represented in the TMT) to 0.5 (where there are equal numbers of men and women in the TMT). We also measured BOD gender heterogeneity using Blau's (1977) index of heterogeneity, and this variable ranged from 0 to 0.5.

is the proportion of TMT group members sorted into separate male and female categories. The Blau's index reflects a variety-based measure of diversity or variability and is used to obtain a relative measure of heterogeneity that is not skewed in favor of either gender (Harrison & Klein, 2007). For TMT gender diversity, Blau's (1977) index ranges from 0 (when only one gender is represented in the TMT) to 0.5 (where there are equal numbers of men and women in the TMT). We also measured BOD gender heterogeneity using Blau's (1977) index of heterogeneity, and this variable ranged from 0 to 0.5.

3.4 Moderating variable

3.4.1 Environmental dynamism (time t)

This variable was computed using industry gross output in revenues. Following prior studies (Keats & Hitt, 1988) we regressed the log-transformed industry gross revenues for the previous 5 years. For example, we calculated environmental dynamism for the year 2007 by back-tracking industry gross revenues in the period from 2002 to 2007, and then regressing industry gross revenues in 2007 against those of 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, and 2006, respectively. The SE of the regression slope was used as the measure of environmental dynamism in 2007. An identical technique was then employed to calculate environmental dynamism for subsequent years.

3.5 Control variables

We included several control variables that can influence the dependent variables. First, we controlled for Past Innovation (innovation during year t). Second, prior studies suggest that foreign ownership structure affects firm performance so we controlled for a firm's foreign ownership (Tuschke & Sanders, 2003). Foreign Ownership was measured as the ratio of foreign-owned capital divided by the total capital. We also included Firm Age measured as number of years since establishment (Barron et al., 1994) and Firm Size measured as the log of the number of employees (Jayaraman et al., 2000).

We also controlled for CEO Power. Following prior studies (Haynes & Hillman, 2010; Krause et al., 2016), we operationalized CEO power as a summed index of three frequently employed measures consistent with previous approaches to measuring CEO power (e.g., Cannella & Shen, 2001; Krause et al., 2015). The three elements included: (1) CEO duality measured as a dichotomous variable with a value of 1 reflecting a combined CEO/board chair, and a value of 0 reflecting a separate CEO and board chair (Finkelstein & D'Aveni, 1994); (2) CEO stock ownership measured as the percentage of outstanding firm stock owned by the CEO (Boeker, 1997); and (3) CEO compensation measured as the ratio of the CEO's salary divided by the total salary of all TMT members. We obtained the three variables from CSMAR's Corporate Governance sub-database. Following prior studies (Haynes & Hillman, 2010) we first standardized the two non-dichotomous variables of CEO Stock Ownership and CEO Compensation to have the same range as the dichotomous variable, CEO Duality. We then aggregated these three variables and standardized them to form an index of CEO power. We also controlled for the Ratio of Outsiders on the Board by considering that outside directors may steer the firm into new businesses. We measured the ratio of outsiders on the board by calculating the number of outside directors on the board divided by total board size. The average value is 0.32 in our sample.

Moreover, we controlled for other TMT demographic-heterogeneity indices as well as board demographic-heterogeneity indices such as TMT (board) age heterogeneity and TMT (board) tenure heterogeneity. Following prior studies (Hillman et al., 2007; Tsui & O'Reilly, 1989; Westphal & Zajac, 1995) we measured TMT (board) age heterogeneity with an analog of the Euclidean distance measure (i.e., the coefficient of variation) commonly used in research on organizational demography. The following formula was used for this calculation:  , where

, where  is the individual age and

is the individual age and  is the value of every other individual's age. We operationalized TMT (board) tenure heterogeneity by following prior studies (e.g., Joshi & Knight, 2015) which classified TMT (board) tenure into groups. Specifically, we had three groups designated as having tenure of less than 3 years, having tenure of 3 to 6 years, and finally having tenure of more than 6 years. We then calculated the TMT tenure heterogeneity and board tenure heterogeneity separately. We also included a set of industry dummy variables in order to control for industry effects, and we controlled for the year effect by generating year dummy variables to include in the analyses.

is the value of every other individual's age. We operationalized TMT (board) tenure heterogeneity by following prior studies (e.g., Joshi & Knight, 2015) which classified TMT (board) tenure into groups. Specifically, we had three groups designated as having tenure of less than 3 years, having tenure of 3 to 6 years, and finally having tenure of more than 6 years. We then calculated the TMT tenure heterogeneity and board tenure heterogeneity separately. We also included a set of industry dummy variables in order to control for industry effects, and we controlled for the year effect by generating year dummy variables to include in the analyses.

3.6 Econometric model

We utilize the panel data econometric model by organizing data into firm-year observation units. The fixed and random effects are the most common models that can control unobserved effects and partially solve the endogeneity problem. The econometric model is written as:  , where

, where  is the dependent variable,

is the dependent variable,  is the vector of explanatory variables that are independent of each other for i and t,

is the vector of explanatory variables that are independent of each other for i and t,  is the vector of coefficients to be estimated,

is the vector of coefficients to be estimated,  is the firm specific unobservable effects, and

is the firm specific unobservable effects, and  is the random error following the normal distribution. Hausman's (1978) specification test was used to detect whether or not a fixed- and random-effects model is most appropriate. The Hausman test was not significant for our models, suggesting that the fixed-effects models were less reliable and efficient than random-effects models.

is the random error following the normal distribution. Hausman's (1978) specification test was used to detect whether or not a fixed- and random-effects model is most appropriate. The Hausman test was not significant for our models, suggesting that the fixed-effects models were less reliable and efficient than random-effects models.

Moreover, time-specific factors such as regulatory changes or economic downturns may also affect innovation and firm performance (Certo & Semadeni, 2006); these omitted variables may cause endogeneity problems. Including time dummy variables in panel data models having a large N (total firms) and a relatively small T (time periods) is useful in reducing the effects of contemporaneous correlation (Certo & Semadeni, 2006). We therefore also included a set of dummy variables for each year in addition to implementing the random-effects model handling the omitted variables (Baltagi, 2013). Innovation can also affect TMT characteristics. For example, a firm that is more likely to accept greater innovation may also be more likely to add TMT members who differ from the current cohort and affect TMT heterogeneity. All of the explanatory variables are accordingly lagged before the dependent variable in order to account for reverse-causality effects. In testing the main effects of TMT gender heterogeneity on innovation, the dependent variable, innovation was predicted at year t + 1 (e.g., 2011), and the independent variables (i.e., TMT gender heterogeneity) and control variables were predicted at year t (e.g., 2010). To test for mediation, we account for the independent variables and control variables at year t (e.g., 2010), and lag innovation to time t + 1 (e.g., one-year change between 2010 and 2011) and firm performance to year t + 2 (e.g., 2012).

3.7 Correcting for selection effects and endogeneity

The endogeneity problem occurs when there are errors (i.e., the true value of independent variables is not observed), an omitted variable (a variable that correlates to both the outcome and one or more explanatory variables is not included in the model), or simultaneous causality (when outcome variables affect explanatory variables and vice versa). Since the explanatory variables are directly observable in annual report logs and TMT information is available in CSMAR's Corporate Governance Database, the errors-in-variables issue is less problematic. Omitted variable bias is less likely because we control for several alternative explanatory variables within a longitudinal setting. Nevertheless, our model could still suffer from simultaneous causality.

In order to alleviate the endogeneity concern in TMT gender diversity and board gender diversity, we include the following instrumental variables addressing endogeneity concerns below. State Ownership. The firm's governance structure may affect the gender heterogeneity in the TMT (Cooper et al., 2014). TMT Size. Prior studies (Hart & Van Vugt, 2006; Thatcher & Patel, 2012) suggest that team size influences the likelihood of attribute alignment (e.g., the homogeneity within a group or between groups will be changed,) so that TMT size influences the likelihood of TMT gender heterogeneity. Board Size. Similarly, a large board size is important for developing more transparent and rigorous corporate governance structures. BOD members with a large board size may need to work closely regardless of the presence of gender heterogeneity, resulting in less conflict, with positive implications for innovation and performance. CEO Gender. P. M. Lee and James (2007) suggest that the CEO's gender would affect the appointments for other TMT members. Board Chair's Gender. The gender of the chair of the board may also affect appointments for board members. We additionally used three-digit industry codes and year dummies. These proposed instrumental variables potentially increase or decrease heterogeneity strength but may be less correlated with yearly performance fluctuations and industry variations. We therefore include Industry Dummies and Year Dummies as instrumental variables.

We followed Cooper et al.'s (2014) approach to assess the exogeneity of our TMT gender-heterogeneity measure using the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test in the “ivreg2” STATA package. First, it is critical to check if some of the excluded instruments are redundant (Hall & Peixe, 2000). An instrument is redundant if its inclusion in the excluded instruments set has no impact on the asymptotic variance covariance matrix of the estimators. We performed the redundant test, which suggests two instrumental variables satisfy the test: CEO Gender and Board Chair's Gender. We then performed an overidentification test. The Hansen J statistic is 0.00 which means these instrumental variables in the test are valid and exactly identified. We further checked for weak identification tests using the Cragg–Donald Wald F test, where the null hypothesis means the instruments are weak. If the Cragg–Donald statistic is above the critical value at significance level of 5% (Stock & Yogo, 2005), then one should reject the null hypothesis that the instrumental variables are not relevant. In our test the Cragg–Donald statistic was 10.51, which is greater than the Stock–Yogo critical value of 7.12 at 10% maximal relative bias. The instruments are therefore relevant and could effectively reduce the threat of endogeneity. Finally, the Endogeneity test of endogenous regressors is 2.35 with p-value = 0.426, which means the specified endogenous regressors can actually be treated as exogenous. Therefore, the TMT gender diversity and board gender diversity measure is exogenous and the unbiased estimates can be reported (Davidson & Mackinnon, 1993).

4 RESULTS

Table 1 shows the summary statistics and correlations. While using TMT women ratio as TMT gender diversity, we computed variance inflation factors (VIF) and observed the maximum VIF value is 1.63, the minimum VIF value is 1.05, and the mean VIF value is 1.21, which are all in an acceptable range (Cohen et al., 2003). There are similar VIF values when using TMT Women Number as TMT gender diversity. An examination of the correlations shows that multicollinearity is not a significant problem. All independent variables were mean-centered before creating the interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991).

| Variables | Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Tobin's Q | 2.63 | 1.35 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| (2) | Innovation | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| (3) | Foreign ownership | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| (4) | Firm age | 11.16 | 4.87 | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| (5) | Firm size (log) | 7.69 | 1.15 | −0.32 | −0.20 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| (6) | CEO power | −0.01 | 1.04 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.20 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| (7) | Ratio of outsiders on the board | 0.32 | 0.09 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| (8) | TMT age diversity | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.05 | −0.09 | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.10 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (9) | BOD age diversity | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.26 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| (10) | TMT tenure diversity | 0.35 | 0.22 | −0.04 | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.23 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.17 | −0.07 | −0.10 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (11) | BOD tenure diversity | 0.37 | 0.22 | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.07 | 0.28 | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.18 | −0.11 | −0.11 | 0.58 | 1.00 | |||||||

| (12) | TMT gender diversity (ratio) | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.15 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 1.00 | ||||||

| (13) | BOD gender diversity (ratio) | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.00 | 0.32 | 1.00 | |||||

| (14) | TMT gender diversity (number) | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.90 | 0.25 | 1.00 | ||||

| (15) | BOD gender diversity (number) | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.94 | 0.31 | 1.00 | |||

| (16) | TMT gender heterogeneity (Blau's) | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.26 | 0.17 | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.97 | 0.24 | 0.90 | 0.21 | 1.00 | ||

| (17) | BOD gender heterogeneity (Blau's) | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.22 | 0.94 | 0.20 | 1.00 | |

| (18) | Environmental dynamism | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.30 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.00 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.07 | −0.18 | −0.21 | 1.00 |

- Note: n = 944. Industry and year are omitted. All correlations above |0.06| are significant at p < 0.05, two-tailed.

- Abbreviations: BOD, board of directors; TMT, top management team.

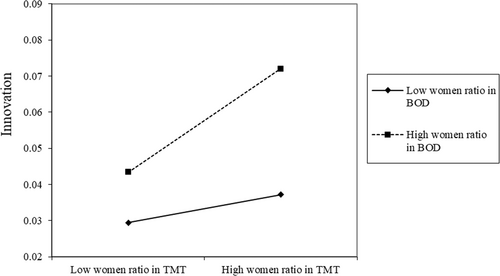

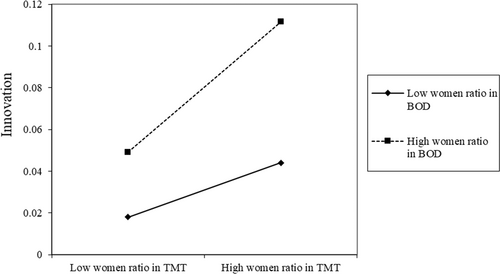

Table 2 reports the results testing for Hypotheses 1 and 2 by using women ratio as an indicator for gender diversity. As shown in Model 3, the coefficient of the interaction term TMT Women Ratio × Board Women Ratio is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.243, p = 0.007). This supports Hypothesis 1. In order to facilitate interpretation, we used the unstandardized coefficients reported in Model 3 of Table 2 to plot the relationship. See Figure 1. As recommended by Aiken and West (1991), we plotted the moderator at 1 SD below and above its mean value. Figure 1 shows that the slope for low board women ratio is 0.02 with p-value of 0.652. The slope for high board women ratio is 0.06 with p-value of 0.005, indicating that the line related to high board women ratio is significantly more positive than the line with low board women ratio.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women ratio | ||||||

| Past innovation | 0.172 | 0.185 | 0.199 | 0.212 | 0.212 | 0.212 |

| (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Foreign ownership | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Firm age | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Firm size (log) | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| CEO power | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Ratio of outsiders on the board | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| TMT age heterogeneity | −0.126 | −0.107 | −0.098 | −0.087 | −0.089 | −0.088 |

| (0.029) | (0.028) | (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | |

| Board age heterogeneity | −0.061 | −0.058 | −0.045 | −0.049 | −0.051 | −0.051 |

| (0.032) | (0.031) | (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| TMT tenure heterogeneity | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Board tenure heterogeneity | −0.019 | −0.021 | −0.023 | −0.023 | −0.024 | −0.025 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Environmental dynamism (ED) | 0.089 | 0.107 | 0.113 | 0.098 | 0.092 | 0.091 |

| (0.021) | (0.020) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.019) | |

| TMT gender diversity − women ratio (TMT) | 0.078 | 0.063 | 0.054 | 0.056 | 0.050 | |

| (0.012) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | ||

| BOD gender diversity − women ratio (BOD) | 0.169 | 0.159 | 0.166 | 0.160 | 0.156 | |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.014) | ||

| TMT × BOD | 0.243 | 0.413 | 0.423 | 0.460 | ||

| (0.007) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |||

| TMT × ED | 0.881 | 0.586 | 0.730 | |||

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.005) | ||||

| BOD × ED | 0.104 | 0.238 | ||||

| (0.014) | (0.009) | |||||

| TMT × BOD × ED | 0.701 | |||||

| (0.006) | ||||||

| Constant | 0.007 | −0.033 | −0.029 | −0.021 | −0.020 | −0.021 |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.013) | |

| Industry dummy | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Year dummy | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Within group R-squared | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Between groups R-squared | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.44 |

| Overall R-squared | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| Wald χ2 | 393.58 | 442.55 | 502.66 | 679.49 | 806.32 | 836.50 |

| Prob > χ2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

- Note: n = 944. p-values in parentheses. All significance tests are based on two-tailed tests. Wald χ2 due to clustered SEs.

- Abbreviations: BOD, board of directors; TMT, top management team.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that the positive effect of TMT–board gender diversity on innovation is moderated by environmental dynamism such that the effect is stronger in dynamic environments than stable ones. The coefficient of the interaction term TMT Women Ratio × Board Women Ratio × Environmental Dynamism is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.701, p = 0.006 in Model 6). This supports Hypothesis 2.

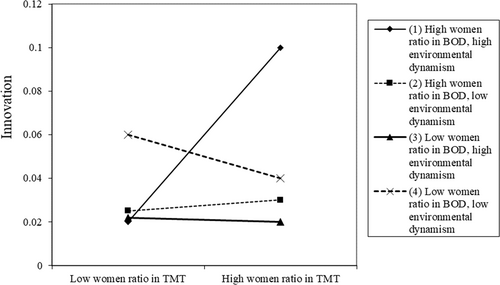

The three-way interaction in Model 6 results in a 0.11 change in R-squared over the two-way interaction represented in Model 3, which is substantial for a three-way interaction (McClelland & Judd, 1993). These results provide support for Hypothesis 2. In Figure 2, we plot the three-way interaction. As shown in Figure 2, the positive association between TMT gender heterogeneity and innovation is more positive under high board gender heterogeneity and high environmental dynamism (Line 1) versus low board gender heterogeneity and low environmental dynamism (Line 4). This is supported with a t-value of simple slope difference between Line 1 and Line 4 of 5.83 (p = 0.000), supporting Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, neither Line 2 nor Line 3 show a significant positive slope lending additional support for our contention that firms with high TMT, high BOD, and high dynamism produce higher levels of innovation.

Next, we examine the moderating role of both BOD gender diversity and environmental dynamism on the indirect effect of TMT gender diversity on Tobin's Q through innovation. Hypothesis 3 predicts that innovation mediates the interactive effect between TMT–board gender diversity and environmental dynamism on firm performance. We followed Mooney and Duval's (1993) approach by testing the moderated mediation effect including all control variables. We used Zellner's (1962) seemingly unrelated regression by invoking Stata syntax “-sureg-” followed by “-nlcom-” which computes point estimates. We then performed nonparametric bootstrap estimations (with 1000 replications) using a 95% confidence interval. We found positive mediation evidence on the Tobin's Q performance measure for TMT gender diversity when board gender diversity and environmental dynamism were both high (effect = 0.13; lower level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.08 and upper level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.21). Hypothesis 3 is supported.

4.1 Post hoc analyses

We adopted several steps in order to test the robustness of the results. First, we provide two alternative measures of TMT gender diversity and board gender diversity using Women Number and Blau's heterogeneity index. For Hypothesis 1, Table 3 shows that the coefficient for the interaction term TMT Women Number × Board Women Number is also positive and statistically significant (β = 0.210, p = 0.008 in Model 2 of Table 3), and the coefficient of the interaction term TMT Gender Heterogeneity × Board Gender Heterogeneity is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.209, p = 0.008 in Model 5), providing support. For Hypothesis 2, the coefficient for the interaction term TMT Women Number × Board Women Number × Environmental Dynamism is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.214, p = 0.028 in Model 3), and the coefficient of the interaction term TMT Gender Heterogeneity × Board Gender Heterogeneity × Environmental Dynamism is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.212, p = 0.038 in Model 6 of Table 3). For Hypothesis 3, we also perform nonparametric bootstrap estimations (with 1000 replications) using a 95% confidence interval. We found positive mediation evidence on performance for TMT women number when board women number and environmental dynamism were both high (effect = 0.02; lower level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.00 and upper level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.05). Similarly, we found positive mediation evidence for TMT gender heterogeneity when board gender heterogeneity and environmental dynamism were both high (effect = 0.23; lower level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.18 and upper level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.29), providing support.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women number | Blau's index | |||||

| Past innovation | 0.194 | 0.210 | 0.214 | 0.195 | 0.209 | 0.212 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Foreign ownership | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Firm age | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Firm size (log) | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.013 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| CEO power | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Ratio of outsiders on the board | 0.109 | 0.103 | 0.096 | 0.113 | 0.105 | 0.096 |

| (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.028) | (0.027) | (0.026) | |

| TMT age heterogeneity | −0.044 | −0.044 | −0.054 | −0.068 | −0.054 | −0.057 |

| (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.031) | (0.030) | (0.029) | |

| Board age heterogeneity | −0.011 | −0.012 | −0.012 | −0.008 | −0.008 | −0.009 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| TMT tenure heterogeneity | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.019 | −0.022 | −0.023 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Board tenure heterogeneity | −0.111 | −0.117 | −0.080 | −0.085 | −0.091 | −0.062 |

| (0.020) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.021) | (0.020) | (0.019) | |

| Environmental dynamism (ED) | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.042 | 0.033 | 0.023 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.008) | |

| TMT gender diversity (TMT) | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.098 | 0.094 | 0.089 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.010) | |

| BOD gender diversity (BOD) | 0.194 | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.195 | 0.857 | 0.986 |

| (0.008) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.009) | (0.057) | (0.056) | |

| TMT × BOD | 0.210 | 0.423 | 0.209 | 0.437 | ||

| (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |||

| TMT × ED | 0.164 | 0.102 | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.004) | |||||

| BOD × ED | 0.140 | 0.909 | ||||

| (0.004) | (0.002) | |||||

| TMT × BOD × ED | 0.214 | 0.212 | ||||

| (0.028) | (0.038) | |||||

| Constant | −0.016 | −0.013 | 0.001 | −0.015 | −0.010 | 0.000 |

| (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| Industry dummy | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Year dummy | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Within group R-squared | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Between groups R-squared | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.46 |

| Overall R-squared | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| Wald χ2 | 317.57 | 649.19 | 992.95 | 391.23 | 566.53 | 954.16 |

| Prob > χ2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

- Note: n = 944. p-values in parentheses. All significance tests are based on two-tailed tests. Wald χ2 due to clustered SEs.

- Abbreviations: BOD, board of directors; TMT, top management team.

Second, we conducted an additional robustness test by using innovation at t + 1 but lagging firm performance at year t + 3. The results are consistent with those using a one-year lag (positive mediation evidence for TMT women ratio when board women ratio and environmental dynamism were both high with effect = 0.23; lower level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.19 and upper level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.28). Finally, while testing the moderated mediation effect we performed a nonparametric bootstrap estimation (with 1000 replications and 10,000 replications) using a 95% confidence interval. The results provide similar support for Hypothesis 3. Thus, we find consistent support for Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3.

5 STUDY 1 DISCUSSION

Intertwined with ongoing economic reforms and practices in marketization with Western influences, and combined with different ownership types of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), private ownership enterprises and multinational corporations (MNCs), Chinese organizations and related HR practices constitute a complex and attractive scholarly puzzle that perhaps has no other comparable counterpart in the world.

Therefore, motivated by both generalizing our theory and satisfying other HRM scholars' interests, we test our findings in a different country. The United Kingdom is chosen as an appropriate context not only for the three abovementioned reasons (see the last paragraph of the introduction), but also for its important role in the world and for the characteristics that are relevant for this study which China does not possess. Like China, the United Kingdom is a major world power considered to be the #5 most powerful country in the world (China is #2; U.S. News, 2021), with the 6th largest gross domestic product in the world (Worldometer, 2021). However, unlike China, the United Kingdom has a more gender egalitarian workforce, as it initially established a voluntary quota of having at least 25% female representation on FTSE100 boards. In 2015, that quota was raised to 33% and the FTSE250 boards were advised to hit the same target by 2020 (Institute of Leadership and Management, 2021). China does not have such quotas. In sum, the United Kingdom provides fertile ground to not only generalize our theory but also test for important HRM cross-country differences.

6 STUDY 2 METHOD

6.1 Data and sample

We constructed our sample by referring to FTSE350 UK public companies. We extracted TMT and BOD characteristic data (e.g., gender, age, tenure, etc.) from BoardEx and obtained the corresponding financial data from the Worldscope database of Datastream. We also constructed a series of control variables that are identical to those control variables used in Study 1. The final UK sample contained 1356 firm-year observations consisting of 245 firms from 2008 to 2015. We then reran the same analyses conducted in Study 1, using the UK data, and reported the reestimated results in Table 4. As shown in Model 3, the coefficient of the interaction term, TMT Women Ratio × Board Women Ratio, is positive and statistically significant (β = 1.280, p = 0.000). We used the estimated coefficients reported in Model 3 to plot the relationship in a similar vein (see Figure 3). The positive association between TMT gender diversity and innovation is more positive under high levels of board gender diversity versus low levels of board gender diversity. This positive difference is statistically significant because the t-value of the simple slope difference between two lines is 5.52 (p = 0.000). These results using the UK data support Hypothesis 1.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women ratio | ||||||

| Past innovation | −0.009 | −0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.832) | (0.991) | (0.461) | (0.381) | (0.357) | |

| Foreign ownership | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.001 |

| (0.483) | (0.562) | (0.543) | (0.654) | (0.453) | (0.567) | |

| Firm age | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.117) | (0.166) | (0.159) | |

| Firm size (log) | 0.017 | −0.002 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.013) | (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.005) | |

| CEO power | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.004) | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.069) | (0.058) | (0.070) | |

| Ratio of outsiders on the board | 0.150 | −0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.058) | (0.840) | (0.664) | (0.766) | (0.769) | |

| TMT age heterogeneity | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.696) | (0.211) | (0.059) | (0.152) | (0.151) | (0.130) | |

| Board age heterogeneity | 0.003 | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.046) | (0.342) | (0.195) | (0.149) | (0.174) | |

| TMT tenure heterogeneity | −0.001 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.313) | (0.286) | (0.587) | (0.334) | (0.148) | (0.166) | |

| Board tenure heterogeneity | −0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.609) | (0.589) | (0.860) | (0.997) | (0.952) | |

| Environmental dynamism (ED) | −0.133 | 0.155 | 0.147 | 0.095 | −0.034 | −0.019 |

| (0.632) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.012) | (0.214) | |

| TMT gender diversity − women ratio (TMT) | 0.694 | 0.532 | 0.011 | 0.021 | 0.182 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.675) | (0.431) | (0.036) | ||

| BOD gender diversity − women ratio (BOD) | 0.831 | 0.680 | 0.680 | 0.091 | 0.154 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.120) | (0.021) | ||

| TMT × BOD | 1.280 | 1.279 | 1.280 | 0.131 | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.024) | |||

| TMT × ED | 0.869 | 0.853 | 0.583 | |||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| BOD × ED | 0.981 | 0.876 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| TMT × BOD × ED | 1.915 | |||||

| (0.051) | ||||||

| Constant | −0.211 | −0.077 | −0.094 | −0.063 | 0.014 | 0.005 |

| (0.269) | (0.020) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.085) | (0.569) | |

| Industry dummy | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Year dummy | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Within group R-squared | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.46 |

| Between groups R-squared | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| Overall R-squared | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Wald χ2 | 654.32 | 675.47 | 690.21 | 704.66 | 724.50 | 741.35 |

| Prob > χ2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

- Note: n = 1356. p-values in parentheses. All significance tests are based on two-tailed tests. Wald χ2 due to clustered SEs.

- Abbreviations: BOD, board of directors; TMT, top management team.

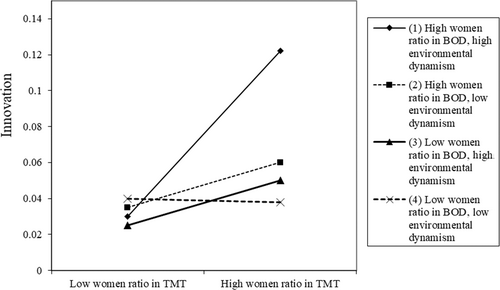

The coefficient of the interaction term, TMT Women Ratio × Board Women Ratio × Environmental Dynamism, is positive and statistically significant (β = 1.915, p = 0.051 in Model 6). This supports Hypothesis 2. We then plot the three-way interaction of the UK data in Figure 4. Similar to that of China in Study 1, Study 2 shows that the positive association between TMT gender diversity and innovation is also more positive under high levels of board gender diversity and high levels of environmental dynamism (Line 1) versus low levels of board gender diversity and low levels of environmental dynamism (Line 4). This is supported with the t-value of simple slopes difference of 4.98 (p = 0.000) between Line 1 and Line 4. Both the estimated results and the interaction plot using the UK data support Hypothesis 2 predicting that the positive effect of TMT–board gender diversity on innovation is moderated by environmental dynamism such that the effect is stronger in dynamic environments than stable ones.

Next, we reexamined Hypothesis 3 using the UK data. The results show a positive mediation effect of innovation on the Tobin's Q performance measure with respect to TMT gender diversity when board gender diversity and environmental dynamism were both high because the mediation effect = 0.19 with the lower level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.15 and the upper level of the bias-corrected confidence interval = 0.23. Values are positive and the confidence interval does not contain zero. Thus, the UK data further support Hypothesis 3 which also received support in Study 1 using the Chinese data.

Furthermore, we reran the analyses by using women number and Blau's index as two alternative measures of TMT gender diversity and board gender diversity (see Table 5). The results in Table 5 are consistent with those in Table 4, further supporting our hypotheses. In conclusion, the results obtained from the UK data (i.e., Study 2) are consistent with that of the Chinese data (i.e., Study 1), suggesting that our theory is generalizable across country context.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women number | Blau's index | |||||

| Past innovation | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.819) | (0.782) | (0.991) | (0.779) | (0.246) | (0.945) | |

| Foreign ownership | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.000 |

| (0.522) | (0.463) | (0.586) | (0.760) | (0.461) | (0.164) | |

| Firm age | 0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.338) | (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Firm size (log) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.023) | (0.012) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.006) | |

| CEO power | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.218) | (0.042) | (0.234) | (0.213) | (0.047) | (0.055) | |

| Ratio of outsiders on the board | −0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.068) | (0.166) | (0.132) | (0.071) | (0.066) | (0.030) | |

| TMT age heterogeneity | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.171) | (0.837) | (0.885) | (0.165) | (0.900) | (0.439) | |

| Board age heterogeneity | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.041) | (0.767) | (0.583) | (0.034) | (0.304) | (0.471) | |

| TMT tenure heterogeneity | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.373) | (0.028) | (0.089) | (0.291) | (0.663) | (0.166) | |

| Board tenure heterogeneity | 0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.674) | (0.406) | (0.173) | (0.532) | (0.010) | (0.055) | |

| Environmental dynamism (ED) | 0.062 | 0.057 | −0.001 | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.012 |

| (0.020) | (0.000) | (0.867) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| TMT gender diversity − women ratio (TMT) | 1.208 | 1.120 | 0.996 | 1.080 | 1.060 | 1.014 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| BOD gender diversity − women ratio (BOD) | 0.213 | 0.130 | −0.046 | 0.089 | 0.070 | 0.019 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.181) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.005) | |

| TMT × BOD | 0.702 | 0.161 | 0.160 | 0.016 | ||

| (0.000) | (0.056) | (0.000) | (0.034) | |||

| TMT × ED | 0.206 | 0.076 | ||||

| (0.006) | (0.000) | |||||

| BOD × ED | 0.293 | 0.084 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| TMT × BOD × ED | 0.901 | 0.293 | ||||

| (0.076) | (0.004) | |||||

| Constant | −0.019 | −0.028 | 0.006 | −0.010 | −0.012 | −0.002 |

| (0.289) | (0.000) | (0.178) | (0.013) | (0.000) | (0.097) | |

| Industry dummy | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |