Considerations for Prognosis, Goals of Care, and Specialty Palliative Care for Hospitalized Patients With Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure

Abbreviations

-

- ACLF

-

- acute-on-chronic liver failure

-

- CPR

-

- cardiopulmonary resuscitation

-

- DC

-

- decompensated cirrhosis

-

- DNR

-

- do-not-resuscitate

-

- EASL

-

- European Association for the Study of the Liver

-

- EASL-CLIF

-

- EASL–Chronic Liver Failure

-

- ESLD

-

- end-stage-liver disease

-

- ICU

-

- intensive care unit

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- MELD-Na

-

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium

-

- OF(s)

-

- organ failure(s)

-

- PC

-

- palliative care

-

- SOFA

-

- sequential organ failure assessment

-

- SPC

-

- specialty palliative care

-

- SPCs

-

- specialty palliative care services

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) occurs in ~25% of hospitalized patients with decompensated cirrhosis (DC)(1) and is associated with high, short-term mortality.(1, 2) The EASL (European Association for the Study of the Liver)/CLIF (Chronic Liver Failure) CANONIC (EASL-CLIF Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis) study showed that 28-day mortality could be predicted after the third day in the intensive care unit (ICU) applying the CLIF-SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment) score.(3) Patients with three or more organ failures (OFs) have been shown to have high mortality risk, with one study demonstrating a 14-day mortality risk worse than status 1A(4) and another showing zero survival for patients with four or more OFs.(3) For ACLF patients listed for liver transplantation (LT), wait-list mortality is as high as 44% within 28 days of listing.(5) Despite this high risk of mortality, prognostication and evaluation for transplantation can be complex, and, in fact, the concept of “too ill for LT” in ACLF has been recently challenged.(6) Given the severity of illness in this population as well as complex informational and symptom management needs, it is worth considering ways that principles of palliative care (PC) can be integrated in the overall management of these patients. As defined by the World Health Organization, PC “is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem of life-threatening illness through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.”(7) PC, at its core, can be provided by anyone on the health care team, so we will use the term specialty palliative care (SPC) to emphasize that it is a specialist seeing the patient. Considering the lack of established guidelines, we propose how PC can be integrated for hospitalized patients with ACLF, including suggestions on how to involve SPC services (SPCs) during evaluation or while listed for LT. We use the traditional term end-stage-liver disease (ESLD) interchangeably with ACLF because most PC literature is based on this traditional concept, and many of these patients would meet ACLF diagnostic criteria.

ACLF Is a Dynamic Syndrome Associated With Poor Outcomes

Using the CANONIC study definition, ACLF is defined as the presence of OFs in patients with DC associated with high short-term mortality.(12) ACLF is different from “mere” acute decompensation without OF, or, in which OFs do not meet ACLF criteria and is associated with lower short-term mortality.(8) ACLF can be further classified according to the number of OFs: ACLF-1 (one OF), ACLF-2 (two OFs), or ACLF-3 (three or more OFs). As expected, increasing number of OFs is associated with higher mortality risk (Table 1). ACLF mortality risk is not a static, but rather a dynamic concept that impacts transplant-free (spontaneous) and posttransplant survival. In the CANONIC study, ACLF resolved or improved in 49.2%, had a steady or fluctuating course in 30.4%, and worsened in 20.4% of cases.(3) However, at 3-7 days in the ICU, it was possible to predict the final grade in 81% and, subsequently, these patients’ 28- and 90-day mortality outcomes.(3) If listed, improvement from ACLF-3 at listing to ACLF-0 to 2 at LT yielded an improvement in 1-year survival from 82% to 88.2%, respectively, particularly in patients aged ≤60 years.(5) In contrast, patients aged >60 years with ACLF-3 have a post-LT survival probability of ~75% at 1 year.(5) Whereas LT outcomes in ACLF at 1 year may be similar to those transplanted for other reasons,(9) ACLF patients have higher wait-list mortality,(10) lower prioritization based on the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium (MELD-Na),(5) making them less likely to receive an LT. PC can provide an extra layer of support in the care of ACLF patients who are hoping for transplant in the face of less favorable outcomes.

| After admission to ICU, ACLF score at 3-7 days predicts 28- and 90-day mortality |

| Unfavorable neurological outcome or dead within 28 days after cardiac arrest(27): |

| ACLF-1: 83% (n = 10) |

| ACLF-2: 93% (n = 13) |

| ACLF-3: 100% (n = 11) |

|

|

1-year posttransplant survival in ACLF patients(5)

|

|

In patients with ACLF-3 |

Specialty Palliative Care Is Underutilized in Hospitalized Patients With ESLD

The use of SPCs specifically in ACLF is unknown, but we can extrapolate the literature from hospitalized patients with ESLD.

SPC has been associated with fewer hospital readmissions to the hospital in patients with ESLD(11-13) and, for patients who ultimately die, with lower use of life-sustaining treatments, shorter lengths of stay,(14, 15) greater reductions in their health care utilization, and higher rates of advance care planning.(16) Despite these benefits, involvement of SPCs in the United States is relatively uncommon, with less than one-third of hospitalized, ESLD patients receiving such services.(15, 17) Compared to patients with advanced cancer, hospitalized ESLD patients tended to receive SPCs later during their hospitalization (at 6.8 vs. 3.4 days), and they were more likely to receive SPCs while in the ICU as compared to those with cancer (27.9% vs. 12.5%).(18) Patients considered for transplant are even less likely to get SPCs.(19) When SPC is consulted, some studies suggest that the vast majority of consults were for goals of care discussions,(18) and that, frequently, consults are requested within the last week of life.(20, 21)

Provider barriers are often attributed to misconceptions about PC principles, such as equating PC with end-of-life care; physician fear that SPCs could upset patients(22); and the misconception that LT-listed patients must remain “full code” at all times. Ufere et al. showed that 84% of responding gastroenterologists agreed that LT wait-listed patients with ESLD should be full code; physicians’ time constraints and limited reimbursement for time spent with goals of care discussions were identified as potential barriers.(23)

Patient or family barriers to accepting SPC involvement include misinterpreting PC as hospice care, or not appreciating the severity of illness, with its risk for rapid death.(24) Future research should investigate strategies for overcoming these barriers.

Do All Patients With ACLF Considering Transplant Need to Be Full Code?

Preferences for life-sustaining treatments, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), frequently are brought up when ESLD patients are critically ill. These preferences were formally analyzed in SUPPORT (Study to Understand Prognosis and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment),(25) which featured a cohort of 575 patients with ESLD who were not candidates for LT followed after an index hospitalization and were nearing death or 6 months from death. Roth et al. showed most patients would rather die than live with a ventilator or a feeding tube; 75% of patients would rather die than live in a coma; 43% of patients would rather die than be placed in a nursing home; and one-third would rather die than be confused or in pain for the rest of their lives. Despite this, 67% of patients still stated that they preferred CPR within 1 month of death. Ultimately, all ESLD patients who received CPR died in this study.(25) A separate cohort study of 1,474 patients with ESLD who received CPR found that only 11% of these patients were able to survive up to hospital discharge, and only 3% of patients were safely discharged home.(26) Roedl et al. followed 1,068 patients with inpatient cardiac arrest and successful CPR; 34 met ACLF criteria. Eighty-three percent (n = 10) of patients with ACLF grade 1, 93% (n = 13) with ACLF grade 2, and 100% (n = 11) with ACLF grade 3 had an unfavorable neurological outcome, as defined by cerebral performance category, overall performance category, or death within 28 days.(27)

These studies highlight the importance of timely goals of care discussions among patients with ACLF to allow for informed end-of-life decisions. For instance, many patients may prefer a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) code status if they had a clear understanding of their likely outcomes in the setting of a code. As mentioned previously, patients considered for transplant are generally expected to have a full-code status. The nuanced approach of placing a DNR order while still pursuing the option of transplant may be appropriate, especially for patients with a low likelihood of getting listed or higher number of OFs. If this approach is chosen, DNR status can be reversed if a patient is called for transplant or other necessary procedures, as appropriate.

Beyond code status, it is important to note that comfort-focused care has been successfully integrated with care of patients seeking LT; in one study, 6 of 157 patients receiving hospice were able to receive a transplant.(28) This approach was feasible, but required a high level of coordination between hospice and transplant teams. Currently, this structure does not exist to provide this type of care in most settings, but we should work toward innovative models such as these to ensure that patients’ goals and preferences are honored throughout the trajectory of illness.

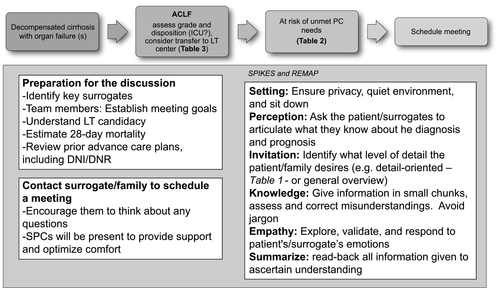

Approaching Goals of Care Discussions in ACLF Patients in the Inpatient Setting

Patients with ACLF and families might find it difficult to raise the topic of prognosis, yet providers should not assume that patients do not want to discuss prognosis, nor should assumptions be made based on cultural background.(29) In many circumstances, patients may not be participatory in these discussions given their critical illness. It is important to include patients in goals of care discussions if willing and able, even if they do not have full decision-making capacity for complex decisions. For patients who do not have decision-making capacity, it is important to identify the correct surrogate decision maker (ideally, a health care agent listed in an advance directive). Some prompts could be: “Some patients/families want to know about things that might happen in the future, is that something you would like me to talk about?”; “Would it be ok if I talk to you about what lies ahead with your illness?”; or, “Today, I wonder if we can talk about how things are going with your medical problems.” An affirmative answer should trigger a formal structured and scheduled family meeting to go over goals of care. Quality measures for ESLD also suggest that sentinel events, such as admission to ICU and serious changes in clinic status, should trigger discussions regarding goals of care.(30) In the inpatient setting, this is often done in the context of a family meeting. One mnemonic that can be used for delivering serious news, such as changes in transplant status or health status, is SPIKES (Setting, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Empathy/Emotions, Summarize).(31) The mnemonic REMAP (Reframe, Expect Emotion, Map Out Patient Goals, Align with Goals, and Propose a Plan) is also helpful for guiding discussions regarding goals of care(32) (Fig. 1). In order to have a successful goals of care discussion, it is important to have a clear understanding of the patient’s prognosis, including a patient’s chances of successfully being listed for transplant and chances of short-term mortality from ACLF. Honest and clear information giving for ACLF patients being considered for LT should acknowledge that a majority of patients will not get a transplant. Other medical teams and some patient-caregiver dyads may also require guidance in the provision of estimates of an individual patient’s risk for short-term mortality or facts about LT in ACLF (Reframe) (Table 1). While remaining optimistic and supporting patients (Expect Emotion), providers should then spend time trying to understand the goals of patients and their caregivers (Map out Patient Goals). These goals should be placed in the context of the patient’s current clinical situation (Align with Goals) in order to make preparations for different scenarios (Propose a Plan). The overall aim is to develop a care plan congruent with the patient’s goals, values, and beliefs. This can include “what if” or “back-up plans” for patients still pursuing aggressive care. For instance, hospice may be the most ideal option for patients and families when a comfort-oriented plan becomes most in line with the patient’s goals. The referring hepatology team may consider an SPC to assist them in clarifying values and goals, discussing symptom relief and, overall, providing “an extra layer of support.”(33) In general, goals of care discussions should be seen as an opportunity to plan in advance, in particular if a patient still has capacity, thus allowing some autonomy over what can feel like a completely out-of-control situation for patients being considered for LT. It also allows patients and families to identify potential outcomes that are deemed as unacceptable quality of life, which would ultimately facilitate transitions in care. Finally, caregiver assessment is critical. The team should validate normal feelings, assess caregiver burden and coping/distress, and provide access to support resources. In addition, SPCs can assess a patient’s symptoms (including depression), spiritual, religious, and cultural beliefs, and their impact on the health condition. Triage decision tools exist to bring ESLD patients to the ICU; however, triggers for including PC in the management of ACLF are lacking. Increasingly, SPCs are available in the inpatient setting across the United States and can be considered at a minimum, in high-risk patients, especially if the patient has unmet needs for communication and/or symptom management.(33) We have defined this high-risk group as ACLF grade 2 or 3, preferably at day 3 after meeting diagnostic criteria, because 81% of patients achieved their final ACLF grade at day 3, which correlates with 28- and 90-day survival rates(3) (Table 2).

| ACLF grade 2 or 3 (at day 3+) |

|

Liver transplant status

difference in goals and expectations between patient, caregiver, and clinical team scores suggesting futility in the ICU after 48-72 hours in ACLF: CLIF-C ACLF score cutoff ≥64-70 |

| Symptom and/or patient/caregiver support |

- * For alcohol: not meeting AASLD ALD Guidance criteria.

- † For example: maximum doses of vasopressors and/or ventilatory support after clinically appropriate period of time, uncontrolled infection.

- Abbreviations: AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; ALD, alcoholic liver disease; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; MI, myocardial infarction.

ACLF Is a Clinical Conundrum for Both Referring and Accepting Hospitals: To Transfer or Not to Transfer?

The heterogeneity and dynamic changes in the clinical course of ACLF preclude simple recommendations in managing this condition, including when to accept a patient on transfer for consideration of LT, which is a common proximal decision. We recommend assessing 28-day mortality either with the number of OFs or providing liver-specific mortality risk scores. Liver-specific scores outperform global scores in ACLF. The development of the CLIF Consortium Organ Failure score, CLIF-C OFs, a liver-specific adaption of the SOFA score derived from the CANONIC study including OF, age, and white blood cell count, showed better accuracy to predict short-term mortality risk compared to other liver-specific scores (C-statistic of 0.79 for CLIF-C ACLF compared to MELD-Na, –0.70; Child-Pugh-Turcotte, –0.70)(34) and is available online at https://bit.ly/2HQ4tBC. These data were also recently validated using a predominantly male Veterans Affairs population with variations of the CLIF-C ACLF model (https://bit.ly/32mF4Jb).(35)

Building on the Predisposing, Injury, Response, and Organ framework, we propose the following dashboard between referring and accepting hospitals to evaluate ACLF transfers (Table 3). Referring hospitals and transplant centers should have dynamic discussions, and the transplant center should track with a secured log of patients accepted and their outcomes to assess whether or not acceptance was appropriate. Given that decisions are frequently attending specific, there should be some standardization of acceptable metrics for both referring hospitals and transplant centers in order to optimize outcomes for patients. If the patient is unlikely to be listed and/or survive listing, providers should also take into consideration costs incurred in family displacement and transport of a deceased patient back home as part of the decision for transfer.

| Item | Components | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | Age | LTC age criteria |

| Frailty: premorbid performance status 1 month before admission* | Premorbid frailty predicts poor post-LT outcomes | |

| Etiology of CLD | LTC may require a period of documented abstinence for alcohol. Minimum psychosocial risk assessment to rule out homelessness/lack of social support | |

| Injury factors | Identify the triggers that led to ACLF: hepatic (hepatitis, alcohol), extrahepatic (GIB, infection, or surgery) | Consider alcohol biomarkers if unable to elicit history of alcohol use |

| Pertinent positive/negative imaging/culture data | ||

| Response | Patient’s location (ICU or not) | After 72 hours, LT assessment and engage PCC |

| If ICU, number of days in ICU | Follow standard of care to tackle trigger(s) | |

| Goal-directed approaches | ||

| Organ | Grade ACLF:1, 2, 3 | ACLF-1: if no contraindications, the best case to transfer |

| Use liver-specific scores 28-day: - CLIF-C ACLF scores | ACLF-2: case-by-case | |

| https://bit.ly/2HQ4tBC or https://bit.ly/32mF4Jb | ACLF-3: case-by-case; however, patients 60+ years have worse post-LT survival | |

| Are there organ/patient’s specific contraindications for LT? | See Table 2 |

- * Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Karnofsky, liver frailty index.

- Abbreviations: CLD, chronic liver disease; GIB, gastrointestinal bleeding; LTC, liver transplant centers; PCC, palliative care consultation.

Conclusions

ACLF is common in hospitalized patients with DC and has very high short-term mortality. There are several scores that triage and prognosticate individual patients with ACLF and determine whether or not these high-mortality patients are candidates for LT, to continue supportive care to bridge them to LT, or to move forward with comfort care measures. We provided several scenarios when SPCs should be considered and tools to structure family meetings when discussing prognosis of ACLF. Although there are now encouraging data to list severe ACLF patients challenging the “too ill for liver transplantation” paradigm,(5, 6, 10) it is important to integrate principles of PC early in ACLF for both patient/caregiver comfort. In the lack of established guidelines, future research should assess the effect on wait-list mortality and quality of life in patients with ACLF regardless of listing status.

Acknowledgment

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Author Contributions

Ruben Hernaez, Arpan Patel, Leanne K. Jackons, Ursula K. Braun, Anne M. Walling and Hugo R. Rosen have done all substantial contributions to conception and design and interpretation of data; and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.