Recurrent Isolated Hyperbilirubinemia From Drug-Induced Impaired Hepatic Bilirubin Uptake

Abbreviation

-

- DILI

-

- drug-induced liver injury

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a common side effect of chemotherapy resulting in jaundice, elevated aminotransferases, and increases in alkaline phosphatase and/or gamma glutamyl transferase. We report a presentation of recurrent, isolated indirect hyperbilirubinemia secondary to cytarabine-based chemotherapy. We hypothesized that drug-induced impaired uptake of bilirubin by the basolateral membrane transporters of the liver such as the organic anion transporting polypeptides OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 resulted in indirect hyperbilirubinemia with each session of cytarabine-based chemotherapy.

Case Report

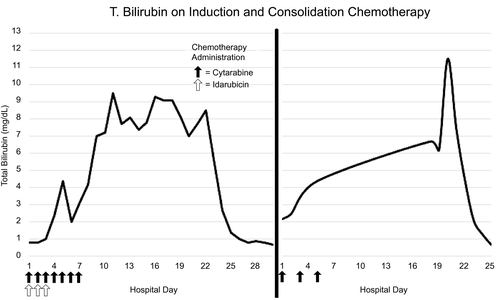

A 19-year-old female with acute myeloid leukemia began induction chemotherapy: 7 days of cytarabine and 3 days of idarubicin. Baseline hepatic panel was normal. On day 4 after induction, total bilirubin rose to 2.4 mg/dL; it peaked at 9.5 mg/dL on day 11 and normalized on day 25 (Fig. 1). Direct bilirubin ranged from 0.2 to 0.7 mg/dL and liver enzymes were normal. Hemolysis markers, haptoglobin and lactate dehydrogenase, were normal, and the direct antiglobulin test was negative. Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative. The patient returned 1 month later for consolidation therapy: cytarabine on days 1, 3, and 5. Hepatic panel was normal at admission. Total bilirubin peaked to 3.7 mg/dL on day 4 of consolidation therapy and subsequently normalized. Direct bilirubin and liver enzymes were normal. The patient returned for second consolidation therapy, after which total bilirubin peaked to 11.5 mg/dL. Direct bilirubin and liver enzymes were unremarkable. Total bilirubin normalized to 0.7 mg/dL (Fig. 1). Genetic testing for Gilbert syndrome was positive for UGT1A1*28 variant allele.

Discussion

DILI is a common and potentially challenging diagnosis for clinicians. DILI can have a hepatocellular pattern, cholestatic pattern, or mixed pattern of liver injury. However, our patient had isolated unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia can come from overproduction of bilirubin (severe hemolysis or massive blood transfusion), reduced uptake of bilirubin by the liver (medications), and/or defects in hepatic conjugation (Gilbert syndrome or Crigler-Najjar syndrome type I and II). Cytarabine can result in DILI, isolated conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in the setting of sepsis, and isolated unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia from hemolysis.1 Chemotherapeutic agents such as cytarabine can also unmask patients with Gilbert syndrome.2 However, in patients with Gilbert syndrome, total bilirubin rarely exceeds 5.0 mg/dL.3 Our patient had a bilirubin elevation over 11 mg/dL, above the expected levels with Gilbert syndrome alone.

Impaired hepatic uptake of bilirubin caused by medications is well described but rarely recognized. Circulating unconjugated bilirubin binds to albumin with high affinity. The basolateral membrane transporters of the liver, including OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 (SLCO1B1 and 1B3),4 selectively uptake and transport the bilirubin into the hepatocytes where conjugation occurs; it is then secreted into the bile by an adenosine triphosphate–dependent pump: multidrug resistance protein 2. Certain drugs, rifampin and pravastatin, can impair the basolateral membrane transporters of the liver.5 We hypothesized that cytarabine impaired the uptake of bilirubin by inhibiting the basolateral membrane transporters of the liver leading to significant indirect hyperbilirubinemia, more than that expected from Gilbert syndrome alone.

In DILI, rechallenge of the offending agent is not recommended because of the risk of acute or chronic liver failure. However, drug-induced impaired hepatic uptake of bilirubin is a process that does not result in liver injury and would be reasonable to reintroduce a potentially life-saving medication, as demonstrated in our patient.

In conclusion, isolated, indirect hyperbilirubinemia can be a rare adverse effect of cytarabine from the impairment of the hepatic uptake of bilirubin. Gilbert syndrome likely accentuated this phenomenon. This is a benign condition that does not cause acute or chronic liver injury. The medication can be safely reintroduced after normalization of bilirubin. Recognition of this mechanism of indirect hyperbilirubinemia is important to avoid unnecessary workup such as a liver biopsy and, more importantly, to avoid discontinuation of a potentially life-saving medication.