Diabetes Is Associated With Increased Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Cirrhosis From Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Abstract

Diabetes increases the risk of liver disease progression and cirrhosis development in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). The association between diabetes and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in NASH patients with cirrhosis is not well quantified. All patients with the diagnosis of NASH cirrhosis seen at Mayo Clinic Rochester between January 2006 and December 2015 were identified. All adult liver transplant registrants with NASH between 2004 and 2017 were identified using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)/Organ Procurement and Transplantation registry for external validation. Cox proportional hazard analysis was performed to investigate the association between diabetes and HCC risk. Among 354 Mayo Clinic patients with NASH cirrhosis, 253 (71%) had diabetes and 145 (41%) were male. Mean age at cirrhosis evaluation was 62. During a median follow-up of 47 months, 30 patients developed HCC. Diabetes was associated with an increased risk of developing HCC in univariate (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.1-11.9; P = 0.04) and multivariable analysis (HR = 4.2; 95% CI = 1.2-14.2; P = 0.02). In addition, age (per decade, HR = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.2-2.6; P < 0.01) and low serum albumin (HR = 2.1; 95% CI = 1.5-2.9; P < 0.01) were significantly associated with an increased risk of developing HCC in multivariable analysis. Other metabolic risk factors, including body mass index, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, were not associated with HCC risk. Among UNOS NASH registrants (N = 6,630), 58% had diabetes. Diabetes was associated with an increased risk of developing HCC in univariate (HR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.1-1.8; P < 0.01) and multivariable (HR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.0-1.7; P = 0.03) analysis. Conclusion: Diabetes is associated with an increased risk of HCC in patients with NASH cirrhosis.

Abbreviations

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- CLD

-

- chronic liver disease

-

- CTP

-

- Child-Turcotte-Pugh

-

- HbA1c

-

- glycated hemoglobin

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- HE

-

- hepatic encephalopathy

-

- HR

-

- hazard ratio

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- MELD

-

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- NAFLD

-

- nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

-

- NASH

-

- nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

-

- OPTN

-

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation

-

- UNOS

-

- United Network for Organ Sharing

Incidence and mortality rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have been increasing in the United States.1-3 Whereas chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been the leading cause of HCC in the United States for the past several decades, successful treatment of chronic hepatitis C with highly potent direct antiviral treatment is decreasing the disease burden of HCV and thus decreasing the number of HCV-associated HCC.2 In contrast to the rapid reduction in HCV-related complications, global prevalence and economic burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are increasing.4-6 HCC is one of most common life-threatening complications of NAFLD. Among NAFLD patients, incidence rates of HCC have been estimated to be 0.44 per 1,000 person-years (range, 0.29-0.66) and 9-26 per 1,000 person-years among patients with NASH cirrhosis.4, 7, 8 NASH has been reported to be the third-leading cause of HCC in the United States.9, 10 Similar epidemiological trends were reflected in recent studies investigating the trends in indications for liver transplantation (LT) in the United States.11 NASH has been emerging as a leading indication for LT and is now the leading indication for LT in women.12 The number of LT registrants with HCC increased 10-fold among NASH patients between 2004 and 2015, reflecting the increasing disease burden of NASH cirrhosis complicated by HCC in the U.S. transplant population.11

Of known risk factors for HCC, diabetes is reported to be responsible for the greatest population-attributable fraction in the United States.13 Multiple studies have shown that diabetes is associated with a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of HCC.14, 15 Diabetes is known to accelerate the progression of fibrosis in patients with NASH.16 It is well known that progression of liver dysfunction is accompanied by insulin resistance and a higher prevalence of diabetes.17, 18 There are very few studies that have evaluated the association between diabetes and HCC in patients with NASH cirrhosis, and the results of these studies were mixed.7, 19, 20 Our recent study showed that diabetes was associated with 2.1-fold increased risk of HCC in non-HCV patients with cirrhosis.20 Because of the small number of patients with NASH cirrhosis, the association between diabetes and HCC in patients with NASH cirrhosis did not reach statistical significance (hazard ratio [HR] of 2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.6-15.8).20

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the association between diabetes and HCC in patients with NASH cirrhosis in an expanded NASH cirrhosis cohort with a longer follow-up. The secondary aim was to investigate the association between other metabolic risk factors (body mass index [BMI], hypertension, and hyperlipidemia) and HCC.

Patients and Methods

Patients

All patients with the diagnosis of NASH cirrhosis of the liver seen at Mayo Clinic Rochester between January 2006 and December 2015 were identified from the institutional research database. Patients with NASH cirrhosis included in our previous study (N = 173)20 were not excluded from the current study. Cirrhosis was defined by liver histology, features of portal hypertension (splenomegaly, esophageal varices, thrombocytopenia [platelets < 150,000], ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy [HE]), or radiographical evidence (nodular contour of the liver or increased liver stiffness >5 kPa measured by magnetic resonance elastography) in the setting of chronic liver disease (CLD). Given that the main aim of the study was to investigate the association between diabetes and development of HCC, only patients who had at least 6 months follow-up with repeat liver images (ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging) were included and patients who had HCC at initial evaluation or within the first 6 months were excluded. The informed consent requirement was waived, and the study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Diagnosis of NAFLD as an underlying cause of cirrhosis was based on clinical (documented history of fatty liver disease), radiological (steatosis noted on radiographic test), or histological (steatosis noted on liver histology) evidence of fatty liver disease or the presence of cryptogenic liver disease with metabolic syndrome at the time of or preceding initial evaluation in the absence of other causes of CLD (chronic viral hepatitis B or C, metabolic, autoimmune, genetic, or biliary liver disease) or significant alcohol consumption (history of alcohol abuse or dependence or documented alcohol consumption of >20 g daily for men and 10 g daily for women) as described.2

For further validation of the association between diabetes and HCC, United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) registry data were obtained to identify all adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) who were registered on the waitlist for LT with the primary or secondary indication of NASH between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2016. Patients with a diagnosis of cryptogenic cirrhosis and BMI ≥ 30 at listing were included as described.11 Patients who had other coexisting liver disease (HCV, hepatitis B virus, alcohol, autoimmune, or other biliary liver disease) or had HCC as an initial listing indication or who developed HCC within the first 6 months after listing were excluded.

HCC Ascertainment

HCC diagnosis was defined by histological confirmation (n = 11) or clinical noninvasive diagnostic criteria (n = 18) according to the guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.21 The latter criteria included a new liver mass of at least 1 cm in diameter with characteristic features of HCC, including both arterial enhancement and delayed washout. In addition, we included patients who had lesions with compatible cross-sectional and angiographic imaging characteristics and who underwent HCC-specific locoregional treatment (n = 1). The diagnosis of HCC among UNOS registrants was based on HCC Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) exception application as described.22 In brief summary, diagnosis of HCC was based on histological or specific imaging criteria (e.g., arterial phase enhancement, venous washout, peripheral rim enhancement, or growth by 50% or more on serial imaging obtained fewer than 6 months apart). To qualify for MELD exception points, the burden of HCC must be either (1) two or three lesions measuring between 1 and 3 cm or (2) a single lesion measuring between 2 and 5 cm. The date of HCC diagnosis was determined by the initial date of a MELD-HCC application, which has been prospectively followed in the UNOS database.

Clinical Information

Clinical information at the time of initial cirrhosis evaluation was collected by medical record review in the Mayo cohort. For the validation cohort, relevant clinical data were extracted from the UNOS database. Diabetes was defined using any of the following criteria: (1) documented history of diabetes, (2) administration of a diabetes medication, or (3) fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) ≥6.5 on two separate occasions in the Mayo Clinic cohort and by self-reported medical history in the UNOS data set. Hypertension diagnosis was based on the documented medical history or current or previous use of antihypertensive medications for the management of high blood pressure. As liver disease progresses, lipid metabolism changes substantially and triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels decrease significantly in patients with cirrhosis.23 For this reason, the diagnosis of hyperlipidemia was based on documented medical history, current or previous use of medication for hyperlipidemia, or a total serum cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, or triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL at any time preceding or at the time of cirrhosis evaluation. Use of diabetes medication (metformin, sulfonylurea, or insulin) was determined at the time of initial cirrhosis evaluation.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical characteristics of the study population were compared between those with and without diabetes using the Student t test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Patients were followed from cirrhosis diagnosis until HCC (event), time of the last radiographical assessment of the liver (censored), or time of LT (censored) in the Mayo Clinic cohort; and from time of waitlist registration until HCC (event), last follow-up (censored), LT (censored), or waitlist removal for any cause (censored) in the UNOS data set. Patients were followed until September 30, 2018 for the Mayo cohort and June 8, 2018 for the UNOS cohort. Cumulative incidence of HCC was estimated considering transplant as a competing risk of HCC in the Mayo Clinic cohort and death or transplant in the UNOS cohort. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was used to investigate the effect of diabetes on the risk of HCC. Given the low number of HCC events observed in the Mayo cohort, a multivariable Cox model was chosen by considering all variables with P < 0.2 in univariate analysis using the c-statistic to determine the “best” model containing up to three covariates using step-wise forward selection. Given that diabetes was the main variable of interest, it was considered in the uni- and multivariate models. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R software (version 3.4.2; R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient Characteristics

The study included 354 patients at Mayo Clinic, of whom 253 (71%) had diabetes (Table 1). Mean age was 61.5 years, and 41% were male. Most patients (94%) were white. As expected, fasting glucose, HbA1C, and the proportions of patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia were higher in diabetics than their nondiabetic counterparts. Follow-up duration was a median of 46 months for diabetics and 47 months for nondiabetics. A total of 38 diabetic patients and 19 nondiabetic patients received LTs. A total of 123 (34.7%) patients died: 93 (36.8%) among diabetics and 30 (29.7%) among nondiabetics. Cause of death was not available in 20 diabetics (22%) and 4 nondiabetics (13%). Among deceased patients with cause of death data available, 67% of diabetics and 64% of nondiabetics died of complications of end-stage liver disease, including HCC. Death because of cardiovascular cause (12% in diabetics and 8% in nondiabetics) and non-HCC malignancies (10% in diabetics and 4% in nondiabetics) were the second and third most common causes of death. There was no statistical difference in the causes of death between the two groups (P = 0.40).

| Diabetes (+) (N = 253) | Diabetes (–) (N = 101) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.5 ± 9.3 | 61.5 ± 11.1 | 0.98 |

| Sex (male) | 104 (41.1%) | 41 (40.6%) | 0.93 |

| Race (white) | 233 (92.1%) | 100 (99.0%) | 0.013 |

| Ascites | 0.50 | ||

| None | 168 (66.4%) | 61 (60.4%) | |

| Mild to moderate (diuretic responsive) | 71 (28.1%) | 32 (31.7%) | |

| Severe (diuretic refractory) | 14 (5.5%) | 8 (7.9%) | |

| HE | 0.78 | ||

| None | 216 (85.7%) | 87 (86.1%) | |

| Grade 1-2 | 35 (13.9%) | 13 (12.9%) | |

| Grade 3-4 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 141.8 ± 56.1 | 99.3 ± 12.6 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| INR | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 0.21 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 0.62 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.93 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 1.9 | 0.019 |

| Platelet count × 109/L, median (IQR) | 114.5 (85, 170) | 121.5 (80.3, 169.8) | 0.98 |

| CTP score | 7.5 ± 1.1 | 7.8 ± 1.2 | 0.018 |

| A (5-6) | 28 (12.2%) | 4 (4.3%) | |

| B (7) | 120 (51.9%) | 47 (51.1%) | |

| B (8-9) | 68 (29.4%) | 32 (34.8%) | |

| C (≥10) | 15 (6.5%) | 9 (9.7%) | |

| MELD score | 10.2 ± 4.2 | 11.0 ± 5.5 | 0.49 |

| Hypertension | 201 (79.4%) | 59 (58.4%) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 195 (78.3%) | 70 (69.3%) | 0.075 |

| BMI | 38.2 ± 19.9 | 34.8 ± 9.6 | 0.10 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) | 203 (81.5%) | 75 (75.0%) | 0.22 |

| Cigarette smoking (ever) | 113 (45.0%) | 33 (33.0%) | 0.052 |

| Bariatric surgery | 13 (5.1%) | 5 (5.0%) | 0.94 |

| Diabetes medication | |||

| Metformin | 128 (51.0%) | — | |

| Insulin | 107 (42.6%) | — | |

| Sulfonylurea | 79 (31.5%) | — | |

| HCC | 27 | 3 |

- Clinical data, including medical and surgical history, ascites, HE, and laboratory result, were collected at the time of initial cirrhosis evaluation.

- Abbreviations: INR, international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

Older Age, Low Albumin, and Diabetes Are Associated With Increased Risk of HCC in the Mayo Cohort

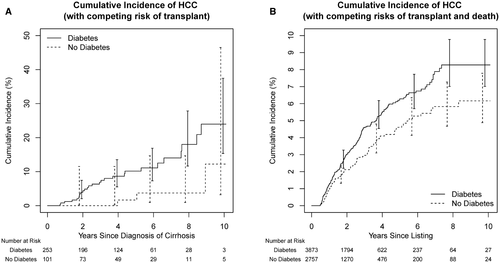

A total of 30 patients developed HCC, including 27 with diabetes and 3 without. Figure 1A shows HCC incidence in diabetics versus nondiabetics. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of HCC was 7.8% (95% CI, 5.1-11.8): 10.2% (95% CI, 6.6-15.5) for diabetics versus 1.7% (95% CI, 2.4-11.5) for nondiabetics. Table 2 summarizes the predictors of HCC development in uni- and multivariable analysis. Among demographic risk factors, older age was associated with an increased risk of HCC. There was a trend toward increased risk of HCC in males and those of nonwhite race. Among variables reflecting severity of liver dysfunction, low albumin level was associated with increased risk of HCC whereas MELD or Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score had no significant association. Low platelet count showed a trend toward association with risk of HCC in univariate analysis (P = 0.07). With regard to medical comorbidities, only diabetes was significantly associated with an increased risk of HCC. Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, BMI, cigarette smoking, and bariatric surgery were not associated with HCC risk. All three risk factors identified in the univariate analysis (older age, albumin, and diabetes) remained significant in the multivariable analysis. The addition of a sex variable in the multivariate model did not impact the effect size of the three independent variables with statistical significance.

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Demography | ||||

| Age (10 years) | 1.59 (1.07-2.38) | 0.02 | 1.75 (1.15-2.64) | 0.008 |

| Male | 2.05 (1.00-4.23) | 0.05 | ||

| Nonwhite race | 2.63 (0.91-7.57) | 0.07 | ||

| Liver dysfunction | ||||

| CTP score | 0.70 (0.46-1.06) | 0.09 | ||

| MELD (per 5 unit) | 1.06 (0.68-1.65) | 0.79 | ||

| Albumin | 0.51 (0.36-0.71) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.35-0.68) | <0.001 |

| INR | 1.07 (0.39-2.94) | 0.90 | ||

| Creatinine | 0.79 (0.32-1.93) | 0.60 | ||

| Bilirubin | 1.04 (0.76-1.42) | 0.83 | ||

| Platelets (per 10 × 10(9)/L) | 0.94 (0.88, 1.01) | 0.07 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 3.62 (1.10-11.9) | 0.04 | 4.18 (1.23-14.20) | 0.02 |

| Hypertension | 0.67 (0.30-1.46) | 0.31 | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.98 (0.43-2.20) | 0.95 | ||

| BMI | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.59 | ||

| Cigarette smoking | 1.14 (0.54-2.38) | 0.73 | ||

| Bariatric surgery | 1.19 (0.28-5.00) | 0.94 | ||

| Medications* | ||||

| Metformin | 1.93 (0.84-4.41) | 0.12 | ||

| Sulfonylurea | 1.50 (0.69-3.23) | 0.31 | ||

| Insulin | 0.66 (0.30-1.48) | 0.32 | ||

- * HR was calculated among diabetics.

- Abbreviation: INR, international normalized ratio.

As an exploratory analysis, we investigated the associations between antidiabetic medications and HCC risk. There was no association between diabetic medications (metformin, insulin, and sulfonylurea) and HCC among diabetics (Table 2).

Association Between Diabetes and HCC in the UNOS Registrants

In the UNOS data set, there were 6,630 patients with NAFLD cirrhosis, of whom 58% had diabetes. Relevant characteristics of the study subjects are summarized in Table 3. Compared to the Mayo Clinic cohort, the UNOS cohort patients were younger, but had a higher mean MELD score.

| Diabetes (+) (N = 3,873) | Diabetes (–) (N = 2,757) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.7 ± 7.2 | 56.4 ± 9.0 | 0.006 |

| Sex (male) | 1,909 (49.3%) | 1,347 (48.9%) | 0.72 |

| Race (white) | 3,097 (80.0%) | 2,261 (82.0%) | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 0.006 | ||

| None | 813 (21.0%) | 612 (22.2%) | |

| Slight | 2,345 (60.6%) | 1,727 (62.7%) | |

| Moderate | 713 (18.4%) | 417 (15.1%) | |

| HE | 0.008 | ||

| None | 1,350 (34.9%) | 1,074 (39.0%) | |

| Grade 1-2 | 2,394 (61.8%) | 1,603 (58.2%) | |

| Grade 3-4 | 127 (3.3%) | 79 (2.9%) | |

| INR | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.1 ± 1.9 | 2.7 ± 2.5 | <0.001 |

| CTP score | 8.3 ± 1.7 | 8.6 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| MELD score | 13.9 ± 4.3 | 14.4 ± 4.5 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 33.1 ± 5.4 | 32.9 ± 5.8 | 0.21 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) | 2,850 (73.7%) | 2,020 (73.4%) | 0.76 |

| HCC | 191 | 100 |

- Abbreviation: INR, international normalized ratio.

During a median follow-up of 21 months, 793 diabetic patients and 468 nondiabetic patients died, whereas 1,223 patients with diabetes and 923 patients without diabetes underwent LT. Regarding the HCC outcome, 291 patients developed HCC during follow-up, including 191 with diabetes and 100 without diabetes. The incidence of HCC was higher in diabetic than nondiabetic patients (Fig. 1B). The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of HCC was 5.6% (95% CI, 4.9-6.3): 6.3% (95% CI, 5.4-7.3) for diabetics versus 4.6% (95% CI, 3.7-5.7) for nondiabetics. Table 4 shows uni- and multivariable analyses replicating the analysis shown in Table 2. In the univariate analysis, age, male sex, higher CTP score, diabetes, and low albumin level were associated with an increased risk of HCC. In the multivariable analysis, age, male sex, diabetes and low albumin level remained independent risk factors for HCC.

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age (10 years) | 1.70 (1.44-2.02) | <0.001 | 1.72 (1.45-2.05) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.58 (1.25-1.99) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.35-2.16) | <0.001 |

| Nonwhite race | 1.02 (0.78-1.35) | 0.86 | ||

| CTP score | 1.08 (1.01-1.16) | 0.03 | ||

| MELD (per 5 unit) | 0.95 (0.83-1.10) | 0.51 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.41 (1.11-1.80) | 0.005 | 1.30 (1.02-1.66) | 0.03 |

| BMI | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.83 | ||

| Albumin | 0.70 (0.58-0.86) | 0.001 | 0.67 (0.54-0.82) | <0.001 |

| INR | 0.97 (0.65-1.45) | 0.89 | ||

| Creatinine | 0.84 (0.68-1.03) | 0.09 | ||

| Bilirubin | 1.01 (0.96-1.07) | 0.70 | ||

- Abbreviation: INR, international normalized ratio.

Next, sensitivity analyses were performed. First, when the diagnosis of NASH was redefined only based on primary or secondary indication of NASH, the results remained similar (Supporting Table S1). Given that MELD score was significantly higher in the UNOS registrants, we did a subgroup analysis after excluding the patients with MELD score higher than 15 and the overall results remained similar (Supporting Table S2). Last, when we included registrants with HCC exception requested within the first 6 months of listing in the UNOS database, the 5-year incidence rates of HCC increased to 6.1%, overall, which came close to the overall HCC incidence rate of 7.8% in the Mayo Clinic cohort. Diabetes was associated with HCC in univariate (HR = 1.55; 95% CI, 1.35-1.90) and multivariable (HR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.19-1.59) analyses.

Discussion

The results of this study identify diabetes as an independent risk factor for HCC among patients with NASH cirrhosis. This finding was validated in the UNOS-NASH registrant cohort. In addition to diabetes, older age and low albumin level were independently associated with the risk of HCC in both the Mayo Clinic and UNOS data sets. On the other hand, other metabolic risk factors, such as high BMI, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia, showed no association with risk of HCC in the Mayo Clinic cohort. Previous studies have shown a chemopreventive effect of metformin against HCC in patients with CLD.24, 25 Given that this association has not been investigated in patients with NASH cirrhosis in the previous studies, we performed exploratory analyses, which showed no association between use of these medications and the risk of HCC in patients with NASH cirrhosis.

Diabetes increases the risk of liver disease progression and cirrhosis development in patients with NAFLD. Diabetes has causal associations with many different types of cancers, including HCC.26 Diabetes promotes hepatocarcinogenesis through activation of inflammatory cascades with production of proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, which cause genomic instability, promote cellular proliferation, and inhibit apoptosis of hepatocytes.27-33 Diabetes may also be associated with hyperinsulinemia and activation of the growth-promoting insulin-like growth factor signaling pathway. Whereas the carcinogenic effect of diabetes is well known, the association between diabetes and HCC among patients with NASH cirrhosis remains unclear.34, 35 One small single-center retrospective cohort study investigated risk factors of HCC in 195 patients with NASH-related cirrhosis.7 A total of 25 HCCs were diagnosed after a median follow-up of 3.2 years. Diabetes was not associated with risk of HCC (HR, 1.0; P = 0.99). Older age and alcohol consumption were independently associated with risk of HCC. Interestingly, high BMI was inversely associated with the risk of HCC (HR, 0.94; P = 0.03). The small number of NASH cirrhosis and HCC cases and a lack of external validation were the major limitations of the study. A subsequent meta-analysis conducted in 2012 concluded that risk factors for HCC in NASH cirrhosis could not be determined because of the small number of eligible studies with insufficient cases and follow up.36 A recent retrospective cohort study used a nation-wide VA database to investigate the risk factors for HCC in patients with cirrhosis.19 This study included 116,404 patients with cirrhosis, of whom 17,354 had NAFLD as the underlying etiology of liver disease. The annual incidence rate of HCC was 0.9% per year. Diabetes was associated with a 2-fold increased risk of HCC whereas BMI showed no association with risk of HCC. A major limitation of the study was the use of International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision codes for the ascertainment of HCC, cirrhosis, and diabetes. Furthermore, NAFLD was classified as an underlying etiology of HCC purely based on risk factors (diabetes and obesity in the absence of other evidence of CLD), which raises concern for misclassification. Another recent VA study showed that diabetes is associated with a 3-fold increased risk of HCC in NAFLD patients after adjusting for covariates.8 In the cirrhosis subgroup, a higher incidence rate of HCC was observed in patients with diabetes (12.4 in diabetics vs. 8.5 in nondiabetics per 1,000 person-years).8 Multivariate analysis was not performed in the cirrhosis subgroup; thus, an adjusted HR was not reported.8 A recent single-center, retrospective, cross-sectional study showed an independent association between diabetes and HCC in patients with NASH cirrhosis who underwent LT. BMI, hypertension, or smoking was not associated with the risk of HCC.37 The cross-sectional study design that measures risk factor and outcome simultaneously prevented the researchers from addressing the potential temporal causal relationship between diabetes and HCC among patients with NASH cirrhosis.38

In addition to older age and diabetes, a low albumin level was independently associated with the risk of HCC. Our previous study indicated that low albumin is associated with the risk of HCC regardless of the etiology of HCC whereas neither Child-Pugh score nor MELD score were associated with HCC risk, suggesting that the association between low albumin and HCC is independent of hepatic dysfunction.20 The impact of low albumin on the risk of HCC (HR = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.32-0.63; P < 0.001) did not change when we excluded patients with abnormal creatinine (>1.2), suggesting that HCC risk is independent of renal impairment. One study showed that addition of exogenous albumin at physiological concentrations resulted in decreased growth of several HCC cell lines in vitro and a decrease in mitogen-activated protein kinase levels and in levels of cyclin D–dependent kinase (Cdk)2 and Cdk4, cyclin E, as well as in alpha-fetoprotein, suggesting a role of albumin in growth inhibition in HCC.39 Another in vitro study showed similar suppressive effect on HCC cell line proliferation with albumin treatment.40 Finally, The Cancer Genome Atlas HCC article recently showed that albumin is one of the most commonly mutated genes in HCC tissues, frequently resulting in truncated albumin variants.41 The mechanistic link between hypoalbuminemia and HCC risk in humans should be further investigated in future studies.

Our study has several limitations. First, there was a small number of HCC cases because of relatively low incidence rates of cancer in patients with NASH cirrhosis. Therefore, the magnitude of association between diabetes and HCC could have been less precise in the Mayo Clinic cohort, with wide CIs. In the univariate analysis, some pertinent variables (e.g., male sex) showed a trend toward a positive association with HCC risk, but did not reach statistical significance. To address this concern, we have validated that diabetes is associated with the risk of HCC using the larger UNOS data set. In addition, old age, male sex, and low albumin level were independent risk factors for HCC in the validation data set. Interestingly, the effect size of diabetes for HCC was much smaller in the UNOS data set. The decreased effect size in the UNOS list could be attributed to selection bias or different degree of severity of liver disease. Given that UNOS registrants had a higher mean MELD score, we performed a sensitivity analysis after excluding patients with MELD scores of 15 or higher. This did not change the analysis results. Although it is difficult to define the strength of association between diabetes and HCC in the current study, the independent confirmation of the association between diabetes and HCC in two different cohorts increases the external validity of the study results. For accurate assessment of the impact of diabetes on HCC risk in patients with NASH cirrhosis, a larger cohort study of well-defined patients with NASH cirrhosis should be conducted. The definition of HCC in the UNOS database may not be completely accurate given that it was based on HCC MELD exception requests. Subjects who are listed for decompensated NASH cirrhosis but then develop HCC beyond Milan criteria and are removed from UNOS could have been censored from analysis and counted as if they did not develop HCC. This could have resulted in slightly lower HCC incidence rates than in the Mayo Clinic cohort. Because our primary analysis excluded UNOS registrants with HCC exception requested within the first 6 months of listing, we performed a sensitivity analysis after including them. The overall incidence rates of HCC increased and the independent association between diabetes and HCC did not change. The UNOS database does not contain information on other comorbidities such as hypertension or hyperlipidemia. Therefore, the lack of association between other metabolic risk factors and HCC has not been validated in the UNOS database. Last, because of the retrospective design of the study, not all relevant variables were available consistently. For instance, duration of diabetes and degree of diabetes control were often missing. HbA1C result was available sporadically mainly in patients with diabetes. Therefore, these variables were not considered in the main statistical analysis. The impact of other protective factors, such as coffee intake, was not evaluated in the current study because the relevant information was not available for most patients. Finally, our study did not show a chemopreventive effect of metformin for HCC development. Whether this lack of association is false or a true negative remains unknown given the relatively small number of cases and lack of granular data. This should be further investigated in a larger prospective study given that the majority of patients with NASH cirrhosis have diabetes and may benefit from metformin treatment.

In conclusion, diabetes was associated with an increased risk of HCC in patients with NASH cirrhosis. Given the global increase in the burden of NASH and HCC, high-risk patients, such as older diabetics with low serum albumin level, should be carefully monitored for HCC development. Future, larger studies should explore whether the effect of diabetes on HCC risk in NASH cirrhosis is modifiable by the type of antidiabetic medication and the effectiveness of diabetes control.