Abdominal Surgery in Patients With Idiopathic Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: A Multicenter Retrospective Study

Abstract

In patients with idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension (INCPH), data on morbidity and mortality of abdominal surgery are scarce. We retrospectively analyzed the charts of patients with INCPH undergoing abdominal surgery within the Vascular Liver Disease Interest Group network. Forty-four patients with biopsy-proven INCPH were included. Twenty-five (57%) patients had one or more extrahepatic conditions related to INCPH, and 16 (36%) had a history of ascites. Forty-five procedures were performed, including 30 that were minor and 15 major. Nine (20%) patients had one or more Dindo-Clavien grade ≥ 3 complication within 1 month after surgery. Sixteen (33%) patients had one or more portal hypertension–related complication within 3 months after surgery. Extrahepatic conditions related to INCPH (P = 0.03) and history of ascites (P = 0.02) were associated with portal hypertension–related complications within 3 months after surgery. Splenectomy was associated with development of portal vein thrombosis after surgery (P = 0.01). Four (9%) patients died within 6 months after surgery. Six-month cumulative risk of death was higher in patients with serum creatinine ≥ 100 μmol/L at surgery (33% versus 0%, P < 0.001). An unfavorable outcome (i.e., either liver or surgical complication or death) occurred in 22 (50%) patients and was associated with the presence of extrahepatic conditions related to INCPH, history of ascites, and serum creatinine ≥ 100 μmol/L: 5% of the patients with none of these features had an unfavorable outcome versus 32% and 64% when one or two or more features were present, respectively. Portal decompression procedures prior to surgery (n = 10) were not associated with postoperative outcome. Conclusion: Patients with INCPH are at high risk of major surgical and portal hypertension–related complications when they harbor extrahepatic conditions related to INCPH, history of ascites, or increased serum creatinine.

Abbreviations

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- HR

-

- hazard ratio

-

- HIV

-

- human immunodeficiency virus

-

- HVPG

-

- hepatic venous pressure gradient

-

- INCPH

-

- idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- PVT

-

- portal vein thrombosis

-

- TIPSS

-

- transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

-

- VALDIG

-

- Vascular Liver Disease Interest Group

Idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension (INCPH) is a heterogeneous group of rare diseases causing portal hypertension and characterized by the absence of cirrhotic modification of the liver parenchyma and the patency of portal and hepatic veins. In Europe, INCPH accounts for <2% of the indications for liver biopsies.1, 2 Liver histological lesions found in patients with INCPH include obliterative portal venopathy, hepatoportal sclerosis, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, and incomplete septal cirrhosis.3 INCPH has been associated with various conditions including thrombophilia, hematologic malignancies, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, genetic and immunological disorders.4, 5 Patients with INCPH may develop portal hypertension–related complications but usually have preserved liver function.

Patients with chronic liver diseases may require abdominal surgery for indications related to their liver disease (e.g., splenectomy or parietal surgery) or unrelated indications. Most available data on the risk of surgery in patients with liver disease pertains to cirrhosis, where postoperative morbidity and mortality are influenced by liver dysfunction and degree of portal hypertension,6-9 type of surgery,10, 11 and comorbidities.9 Given the link between portal hypertension and postoperative outcome,11 portal decompression has been proposed to facilitate abdominal surgery and improve outcome, although reported results are contrasted.12-17

Experience regarding abdominal surgery in patients with INCPH is mostly limited to portosystemic shunt and/or splenectomy performed in adults or children from eastern countries.5, 18-20 The present study thus aimed at evaluating the outcome of patients with INCPH undergoing abdominal surgery and at assessing the impact of preoperative portal decompression procedures.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Between April 2017 and November 2017, we contacted all of the centers participating in the Vascular Liver Disease Interest Group (VALDIG) or the French network for vascular liver diseases to retrospectively identify all patients with INCPH having had one or more abdominal surgery. Surgeries were considered only if INCPH was known prior to the procedure or diagnosed at the time of the surgery. Patient identification was based on local databases. The study was approved by our institutional review board without need for informed consent (CCER 2017-01219) and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Definitions

Diagnosis of INCPH was based on the criteria proposed by VALDIG, after exclusion of cirrhosis (Supporting Table S1). Histologic diagnosis of INCPH was confirmed by pathologist experts in liver diseases. Patients with portal vein thrombosis (PVT) were included in this study if this thrombosis occurred after INCPH diagnosis. Patients with chemotherapy-induced noncirrhotic portal hypertension and/or who underwent liver resection for colorectal liver metastasis were not included because the main liver lesion in these patients is sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, i.e., a distinct entity from INCPH.21

Date of diagnosis of INCPH was the date of the first liver biopsy demonstrating the absence of cirrhosis while signs of portal hypertension were already present, as detailed in Supporting Table S1. According to previous reports, extrahepatic conditions associated with INCPH were classified into the following categories22-25: immunological disorders (autoimmune conditions, common variable immune deficiency, history of solid organ transplantation, Crohn's disease, HIV infection), recurrent abdominal infections, medication or toxins, prothrombotic state (myeloproliferative syndrome, heterozygous factor II or V Leiden, or familial history of venous thromboembolism), genetic disorders.

The following data were collected at surgery: (1) clinical features before surgery, including age, gender, American Society of Anesthesiology class,26 age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index (the Charlson Comorbidity index is a weighted index that takes into account the number and the seriousness of comorbid diseases by assigning points for certain illnesses27; the age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index assigns an additional point for each decade of life after 50 years of age), clinical, laboratory, imaging, and endoscopic features; (2) surgical data, including indication, type of surgery, planned or emergency procedure, and laparoscopy or laparotomy. Major surgery was defined as laparotomy with operative intervention on a visceral organ.9 History of ascites was defined as a previous ascites that was controlled with diuretics at the time of surgery or clinically detectable ascites at surgery. Portal decompression intervention before surgery included transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS) placement or surgical portosystemic shunt. Patients in whom surgical portosystemic shunt was the indication for surgery were not included.

Follow-Up

Duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of surgery. Endpoints were prespecified before data collection (Supporting Table S2). Postoperative complications were defined as any event occurring within 1 month after surgical intervention and categorized according to the Dindo-Clavien classification.28 Portal hypertension–related complications were defined as any of the following: decompensation ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, significant portal hypertension–related bleeding,29 acute kidney injury, or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis occurring within 3 months after surgical intervention (Supporting Table S2). Decompensation of ascites was defined as follows: (1) in patients without ascites, onset of clinically detectable ascites, confirmed by ultrasonography; (2) in patients with previous ascites not requiring paracentesis, ascites requiring two or more paracenteses within 3 months following surgery or requiring a TIPSS. Postoperative death was defined as death occurring within 6 months after surgical intervention. Finally, an unfavorable outcome was defined as either postoperative grade ≥ 3 complication according to the Dindo-Clavien classification within 1 month after surgery, portal hypertension–related complications within 3 months after surgery, or death within 6 months after surgery.

In order to evaluate the influence of portal decompression on postoperative outcome, we compared the occurrence of complications between patients who had and those who did not have a history of a portal decompression procedure, i.e., TIPSS placement or surgical portosystemic shunt, performed before abdominal surgery.

Controls

We compared 6-month postoperative cumulative risk of death in patients with INCPH with that of patients with cirrhosis who had abdominal surgery, selected from a recently published cohort.17 Two patients with cirrhosis were matched with one patient with INCPH according to the presence of ascites at surgery (either clinically detectable ascites before TIPS placement or history of ascites at the time of surgery, i.e., previous ascites controlled with diuretic therapy at surgery or clinically detectable ascites at surgery).

We also compared 3-year liver transplantation–free survival of patients with INCPH who had abdominal surgery, i.e., patients from the present cohort, with that of patients with INCPH who did not undergo abdominal surgery, prospectively included between January 2011 and June 2018 at the liver hemodynamic unit at Beaujon Hospital (Clichy, France). Diagnosis of INCPH was based on the criteria proposed by VALDIG, after exclusion of cirrhosis (Supporting Table S1). Among the 101 patients meeting these criteria, 7 were excluded because they were referred to the liver hemodynamic unit for evaluation before liver transplantation, 9 because follow-up data were not available, and 3 because they were already included in the present study.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or absolute number (percentage). Comparisons between quantitative variables were performed using the t test or Mann-Whitney test for normally and nonnormally distributed variables, respectively. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine whether or not the distribution of continuous variable was normal. Comparisons between categorical variables were performed using the chi-squared or Fisher exact test, when appropriate. Univariate Cox regression analyses were performed to determine factors associated with postoperative complication grade ≥ 3 within 1 month after surgery, portal hypertension–related complications within 3 months after surgery, death within 6 months after surgery, or unfavorable outcome after surgery. Factors included in the univariate analysis were prespecified based on their previous identification as prognostic factors in patients with cirrhosis undergoing surgery and/or in patients with INCPH. These factors included age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index,9 extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH,23-25 history of ascites at the time of surgery (i.e., previous ascites controlled with diuretic therapy at surgery or clinically detectable ascites at surgery),23-25, 30 varices needing treatment (i.e., medium/large esophageal and/or gastric varices, history of variceal bleeding, or history of endoscopic band ligation and/or glue),11, 30 PVT at surgery,22 serum bilirubin at surgery,8, 9, 30, 31 serum creatinine at surgery,8, 9, 24, 30, 32 major surgery,9, 10 and emergency procedures.6-8, 31 Although Model for End-Stage Liver Disease and Child-Pugh scores are known to be associated with postoperative outcome after abdominal surgery in patients with cirrhosis,9, 31, 32 we deliberately chose not to insert these scores but rather serum creatinine and bilirubin because 6 patients were treated with vitamin K antagonists and serum albumin concentration was available in only 34/44 patients. We did not analyze hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) because HVPG is not a good reflection of portal hypertension in patients with INCPH.25, 33

In order to assess the influence of portal decompression on postoperative outcome, we performed additional analyses including portal decompression in the Cox regression analysis. Hazard ratios (HRs) for Cox logistic regression were provided with their 95% confidence interval (CI). Cumulative risk of death was assessed according to the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. All tests were two-sided, and P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant. Data handling and analysis were performed with SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient Characteristics at Surgery

Between 2002 and 2017, 45 surgical interventions were performed in 44 patients from 10 centers participating in the VALDIG network or the French network for vascular liver disease (Supporting Table S4). Their characteristics at the time of surgery are presented in Table 1. INCPH was diagnosed at the time of surgery in 8 (18%) patients. In the 36 other patients, median time between INCPH diagnosis and surgery was 26 (6-50) months. Prevalence of signs of portal hypertension at INCPH diagnosis, namely ascites and gastroesophageal varices, was similar between the 8 patients in whom INCPH was diagnosed at surgery and the 36 patients with known INCPH at surgery (data not shown). At least one extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH was present in 25 (57%) patients, including 23 with either immunological disorder or HIV infection. Fourteen (32%) had two or more conditions. Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index was ≥ 3 in 35 (80%) patients, indicating that significant comorbidities were common. Liver function was preserved in the majority of the patients because 32 (73%) patients had serum bilirubin ≤ 34 μmol/L, 32 (73%) had an international normalized ratio < 1.5, none had hepatic encephalopathy, and only 7 (16%) had clinically detectable ascites, including 2 (5%) with tense ascites at surgery (Table 1). Eleven (25%) patients had serum creatinine ≥ 100 µmol/L before surgery. HVPG was measured in 28 (64%) patients. Median (IQR) HVPG was 9 (6-15) mm Hg.

| Characteristics | Patients With Available Data | Number (Percentage) or Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | ||

| Male gender | 44 | 30 (68) |

| Age, years | 44 | 53 (37-65) |

| Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index | 44 | 4 (3-6) |

| ASA score | 44 | 3 (2-3) |

| At least one extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH | 44 | 25 (57) |

| Immunological disorder | 18 (41) | |

| HIV infection | 5 (11) | |

| Recurrent abdominal infection | 5 (11) | |

| Medication or toxin | 5 (11) | |

| Prothrombotic condition | 2 (5) | |

| Genetic disorder | 2 (5) | |

| At least one other cause of chronic liver disease | 44 | 11 (25) |

| Excessive alcohol consumption | 2 (4) | |

| Metabolic syndrome | 5 (11) | |

| Hepatitis C virus infection | 4 (9) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 | 13 (30) |

| Ascites | 44 | |

| Absent | 28 (64) | |

| Controlled with diuretics | 9 (14) | |

| Clinically detected | 7 (16) | |

| History of ascites* | 44 | 16 (36) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 44 | 0 (0) |

| Previous variceal bleeding | 43 | 18 (42) |

| Treatment before surgery | ||

| Anticoagulation therapy | 43 | 16 (36) |

| Antiplatelet agents | 43 | 7 (16) |

| Diuretic therapy | 43 | 15 (34) |

| Beta-blockers | 43 | 18 (41) |

| Endoscopic data | ||

| Gastroesophageal varices | 42 | |

| Absent | 10 (24) | |

| Small | 10 (24) | |

| Medium or large | 22 (52) | |

| Varices needing treatment† | 30 (71) | |

| Imaging data | ||

| Portosystemic collaterals at imaging | 43 | 25 (58) |

| Spleen size, cm | 35 | 16 (14-20) |

| Previous splenectomy | 45 | 3 (7) |

| Thrombosis of the portal venous axis | 43 | 6 (14) |

| Partial occlusion | 3 (7) | |

| Complete occlusion | 3 (7) | |

| Laboratory data | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 42 | 11.8 (10.0-13.9) |

| Leukocyte count, ×109/L | 41 | 5.2 (3.4-10.0) |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 42 | 87 (67-161) |

| INR | 42 | 1.13 (1.02-1.47) |

| AST, IU/L | 43 | 32 (25-47) |

| ALT, IU/L | 42 | 26 (19-37) |

| ALK, IU/L | 41 | 136 (77-251) |

| GGT IU/L | 42 | 57 (23-127) |

| Serum bilirubin, μmol/L | 43 | 17 (12-35) |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/L | 44 | 79 (61-106) |

| Serum albumin, g/L | 34 | 37 (31-41) |

| MELD score | 39 | 9 (7-12) |

- * History of ascites at surgery was defined either as a previous history of ascites that was controlled with diuretics at the time of surgery or clinically detected ascites at surgery.

- † Medium/large esophageal and/or gastric varices or history of variceal bleeding or history of endoscopic band ligation and/or glue.

- Abbreviations: ALK, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; INR, international normalized ratio; IU, international unit; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

Sixteen (36%) patients were treated with anticoagulants before surgery, including low–molecular weight heparin (n = 7), nonfractioned heparin (n = 1), fondaparinux (n = 1), rivaroxaban (n = 1), and vitamin K antagonists (n = 6). Among these 16 patients, anticoagulation was stopped before surgical intervention in 8 patients. Thus, 8 (18%) patients were still treated with anticoagulation therapy at the date of surgery. Seven (16%) patients were treated with antiplatelet agents before surgery, including aspirin (n = 6) and clopidogrel (n = 1). Among these 7 patients, antiplatelet agents had been stopped before surgical intervention in 2 patients. Thus, 5 (11%) patients were still treated with antiplatelet agents at the date of surgery.

Type of and indications for abdominal surgery are detailed in Table 2. One patient underwent two different operations (emergency surgery for perforated gastric ulcer suture, followed by elective abdominoplasty, 2 years later). There were 15 (33%) major and 30 (67%) minor interventions (including 12 laparoscopic surgeries). Eleven interventions (24%) were emergency surgeries, whereas the 34 (76%) remaining were planned interventions. Among the 7 patients with elevated serum creatinine concentration (i.e., ≥ 100 µmol/L) and a history of ascites at surgery, 3 had major surgery and 2 others had emergency surgery (Supporting Table S5). In the perioperative period, red blood cells and platelets were transfused in 11 (24%) and 8 (18%) patients, respectively.

| Minor surgeries | 30 |

| Open surgeries | 18 |

| Abdominal wall | 13 |

| Hernia repair | 10 |

| Alfapump implantation | 1 |

| Abdominoplasty | 1 |

| Surgical exploration | 1 |

| Cholecystectomy | 2 |

| Retroperitoneum mass excision | 1 |

| Appendicectomy | 1 |

| Cesarean section | 1 |

| Laparoscopic surgeries | 12 |

| Abdominal wall | 2 |

| Surgical exploration | 1 |

| Peritoneal catheter placement | 1 |

| Cholecystectomy | 4 |

| Splenectomy | 1 |

| Colorectal surgery | 4 |

| Ileal resection (Crohn's disease) | 2 |

| Appendicectomy | 2 |

| Partial liver resection | 1 |

| Major surgeries | 15 |

| Urologic or kidney surgery | 5 |

| Renal transplantation | 2 |

| Nephrectomy | 2 |

| Renal carcinoma | 1 |

| Bleeding after renal biopsy | 1 |

| Cystectomy and hysterectomy for urothelial carcinoma | 1 |

| Splenectomy | 5 |

| Splenectomy alone | 3 |

| Splenectomy + caudal pancreatectomy | 1 |

| Splenectomy + portocaval shunt | 1 |

| Colic resection | 2 |

| Crohn's disease | 1 |

| Colorectal cancer | 1 |

| Gastric and pancreatic surgery | 2 |

| Gastrectomy for gastric neoplasia | 1 |

| Pancreatectomy for neuroendocrine neoplasia | 1 |

| Partial liver resection | 1 |

Postoperative Complications Within 1 Month After Surgery

According to the Dindo-Clavien classification, 61 postoperative complications occurred in 31 (70%) patients within 1 month after surgery (Table 3). A median of 2 (1.0-3.0) complications occurred per patient. In 9 (20%) patients, postoperative complications were classified as grade ≥ 3 or more according to the Dindo-Clavien classification.

| Type of complication | |

|---|---|

| Infection | 19 |

| Lung | 5 |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 |

| Skin infection | 3 |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 3 |

| Cholangitis | 1 |

| Clostridium difficile infection | 1 |

| No source identified | 3 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 10 |

| Fistula/leak | 5 |

| Abdominal leak | 3 |

| Urinary leak | 2 |

| Digestive complications | 5 |

| Vomiting | 2 |

| Ileus | 3 |

| Cardiopulmonary | 8 |

| Respiratory failure | 1 |

| Venous thrombosis | 2 |

| Pleural effusion | 3 |

| Hypotension | 1 |

| Tako-Tsubo syndrome | 1 |

| Liver | 1 |

| Moderate liver failure | 1 |

| Neurologic | 1 |

| Confusion | 1 |

| Pain* | 7 |

| Other | 5 |

| Diabetes decompensation | 4 |

| Anemia | 1 |

- * All seven reported complications were classified grade 1 according to the Dindo-Clavien classifications (i.e., any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for additional treatment).

Ten (22%) patients developed postoperative bleeding, including 4 classified as grade ≥ 3 according to the Dindo-Clavien classification. Three patients required an intervention (surgical or radiological), and 2 required transfusion of red blood cells and/or platelet units (Supporting Table S6). Antiplatelet agents at surgery (3/10 [30%] versus 2/35 [6%], P = 0.03) as well as anticoagulation (5/10 [50%] versus 3/35 [9%], P = 0.003) were the only factors associated with postoperative bleeding among those tested, as indicated in Table 1. Platelet count at surgery was similar in patients with or without postoperative bleeding (P = 0.6).

Nineteen postoperative infections occurred in 15 (33%) patients, including only one classified as grade ≥ 3 according to the Dindo-Clavien classification. No patient developed postoperative liver failure.

None of the prespecified factors were significantly associated with the development of at least one grade ≥ 3 complication according to the Dindo-Clavien classification (Table 4).

| HR | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one grade 3 or more complication within 1 month after surgery (n = 9) | ||||

| Age-adjusted comorbidity index | 1.103 | 0.866 | 1.404 | 0.427 |

| Extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH | 1.387 | 0.331 | 5.810 | 0.654 |

| History of ascites* | 1.340 | 0.300 | 5.988 | 0.702 |

| Varices needing treatment† | 2.056 | 0.240 | 17.600 | 0.511 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 2.104 | 0.363 | 12.196 | 0.407 |

| Serum bilirubin | 1.012 | 0.994 | 1.031 | 0.189 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.002 | 0.999 | 1.006 | 0.188 |

| Major surgery | 0.556 | 0.138 | 2.242 | 0.409 |

| Emergency procedure | 2.920 | 0.712 | 11.981 | 0.137 |

| At least one portal hypertension related complication‡ within 3 months after surgery (n = 16) | ||||

| Age-adjusted comorbidity index | 1.074 | 0.913 | 1.264 | 0.390 |

| Extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH | 3.973 | 1.129 | 13.982 | 0.032 |

| History of ascites * | 3.144 | 1.162 | 8.504 | 0.024 |

| Varices needing treatment† | 0.858 | 0.298 | 2.472 | 0.777 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 0.750 | 0.170 | 3.304 | 0.704 |

| Serum bilirubin | 0.991 | 0.972 | 1.012 | 0.401 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.002 | 0.999 | 1.005 | 0.112 |

| Major surgery | 0.634 | 0.236 | 1.704 | 0.366 |

| Emergency procedure | 1.676 | 0.581 | 4.830 | 0.339 |

| Death within 6 months after surgery (n = 4) | ||||

| Age-adjusted comorbidity index | 1.372 | 1.040 | 1.810 | 0.025 |

| Extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH | 0.800 | 0.113 | 5.679 | 0.823 |

| History of ascites* | 5.292 | 0.550 | 50.919 | 0.149 |

| Varices needing treatment† | 1.116 | 0.116 | 10.728 | 0.925 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 0.039 | <0.001 | 6466.507 | 0.597 |

| Serum bilirubin | 0.797 | 0.622 | 1.022 | 0.074 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.007 | 1.003 | 1.012 | 0.002 |

| Major surgery | 0.487 | 0.069 | 3.455 | 0.471 |

| Emergency procedure | 0.992 | 0.103 | 9.540 | 0.994 |

| Unfavorable outcome after surgery § (n = 22) | ||||

| Age-adjusted comorbidity index | 1.099 | 0.963 | 1.254 | 0.163 |

| Extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH | 2.410 | 0.939 | 6.186 | 0.067 |

| History of ascites * | 3.892 | 1.650 | 9.180 | 0.002 |

| Varices needing treatment† | 1.007 | 0.390 | 2.598 | 0.989 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1.425 | 0.479 | 4.237 | 0.524 |

| Serum bilirubin | 0.999 | 0.985 | 1.014 | 0.901 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.003 | 1.000 | 1.005 | 0.056 |

| Major surgery | 0.851 | 0.356 | 2.032 | 0.716 |

| Emergency procedure | 2.136 | 0.865 | 5.276 | 0.100 |

- Bold indicates significant associations.

- * History of ascites at surgery was defined either as a previous history of ascites that was controlled with diuretics at the time of surgery or clinically detected ascites at surgery.

- † Medium/large esophageal and/or gastric varices or history of variceal bleeding or history of endoscopic band ligation and/or glue.

- ‡ Portal hypertension–related complications were defined as any of decompensation ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, significant portal hypertension–related bleeding, acute kidney injury, or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis occurring within 3 months after surgical intervention. Decompensation of ascites was defined as follows: (1) in patients without ascites, onset of clinically detectable ascites, confirmed by ultrasonography; (2) in patients with previous ascites not requiring paracentesis, ascites requiring two or more paracenteses within 3 months following surgery or requiring a TIPSS.

- § An unfavorable outcome after surgery was defined as either postoperative complication grade ≥ 3 within 1 month after surgery or portal hypertension–related complications within 3 months after surgery or death within 6 months after surgery.

Portal Hypertension–Related Complications Within 3 Months After Surgery

Twenty-seven portal hypertension–related complications occurred in 16 (36%) patients within 3 months after surgery. Median time between surgery and occurrence of such complications was 6 (1-17) days. Decompensation of ascites, occurring in 12 (26%) patients, was the most frequent of such complications. In two patients, a TIPSS was placed for refractory ascites, 5.9 and 7.5 months after surgery, respectively. Hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and acute kidney injury occurred in 3 (7%), 2 (4%), 3 (7%), and 7 (16%) patients, respectively. One patient had TIPSS placement for refractory variceal bleeding 14 days after surgery. Resolution of a portal hypertension–related complication occurred in 15 out of the 16 patients, after 26 (10-59) days. One patient died 5.7 months after surgery (patient 7, Table 5). Length of hospital stay was significantly longer in patients who developed portal hypertension–related complications than in those who did not (30 [6-45] days versus 6 [3-16] days, P = 0.002).

| Patient 7 | Patient 8 | Patient 20 | Patient 41 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient's features at surgery | ||||

| Age, years | 73 | 65 | 51 | 66 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Age-adjusted charlson comorbidity index | 8 | 6 | 9 | 8 |

| ASA score | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH | Previous renal transplantation | None | None | Recurrent abdominal infection |

| Azathioprine | ||||

| NOD2 mutation | ||||

| Ascites | None | Tense | Diuretic-sensitive ascites | Tense |

| History of variceal bleeding | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Esophageal varices | Medium size | Absence | Medium size | Medium -size |

| Portal vein thrombosis | No | No | No | No |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 99 | 273 | 144 | 52 |

| INR | 1 | 1 | 0.94 | 1.16 |

| Serum bilirubin, μmol/L | 16 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/L | 533 | 300 | 552 | 143 |

| MELD | 14 | 12 | 14 | 9 |

| Surgery | ||||

| TIPSS performed before surgery | No | Yes | No | No |

| Surgical intervention | Renal retransplantation | Peritoneal catheter placement | Nephrectomy | Alfapump implantation |

| Indication | End-stage renal failure | Refractory ascites | Fistula after renal biopsy | Refractory ascites |

| Postoperative outcome | ||||

| Occurrence of portal hypertension–related complication after surgery | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Ascites | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | |||

| Variceal bleeding | ||||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | ||||

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | ||||

| Other postoperative complication | Leakage | Wound infection | Pleural infection | None |

| Tako-Tsubo syndrome | ||||

| Acute kidney injury | ||||

| Duration between surgery and death | 5.7 months | 2.2 months | 4.3 months | 3.8 months |

| Cause of death | Variceal bleeding | Cardiac arrest | Pneumonia | Septic shock |

- Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NOD2, nucleotide binding oligomerization domain containing 2.

Factors associated with the occurrence of at least one portal hypertension–related complication included a history of ascites and extrahepatic conditions associated with INCPH. Serum creatinine at surgery was not associated with the occurrence of at least one portal hypertension–related complication (Table 4).

PVT After Surgery

Five (11%) patients developed de novo PVT, 28 (range 1-45) days after surgical intervention (Supporting Table S7). Interestingly, three out of these five surgeries were splenectomies, whereas two involved other surgical interventions. PVT occurred in 3 out of the 6 patients (50%) who had splenectomy versus 2 out of the 39 (5%) who had another surgical intervention (P = 0.01). Overall, complete recanalization was observed in 3 of 5 patients. Two out of the 3 patients received anticoagulation, and complete recanalization was observed after 4 and 5.5 months, respectively. The third patient did not receive anticoagulation because a TIPSS was inserted; complete recanalization was observed after 8 months.

Death After Surgery

Thirteen (29%) patients were admitted to the intensive care unit after surgery, with a median (IQR) length of stay in the intensive care unit of 4 (2-7) days. Median (IQR) overall length of hospital stay was 10 (4-28) days. Four patients died within 6 months after surgery. Their characteristics are presented in Table 5. None of the patients underwent liver transplantation within the observation period.

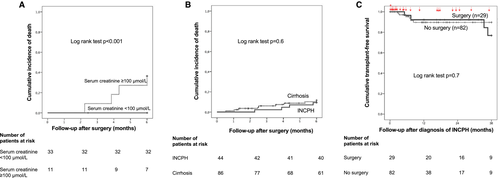

Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index and serum creatinine level were associated with death within 6 months after surgery (Table 4). Patients with age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 6 before surgery had a 6-month cumulative risk of death of 27% versus 0% for patients with an index below this threshold (P = 0.002). We have previously reported that serum creatinine level > 100 µmol/L is associated with a poor outcome after TIPSS in patients with INCPH.25 Using this threshold here, we observed that patients with serum creatinine ≥ 100 μmol/L had a 6-month cumulative risk of death of 33% versus 0% for patients with serum creatinine below this threshold (Fig. 1).

We compared 6-month cumulative risk of death after abdominal surgery of patients with INCPH to that of patients with cirrhosis matched according to the presence of ascites at surgery. One patient with INCPH could not be matched according to the presence of ascites, explaining why 43 patients with INCPH were compared to 86 patients with cirrhosis. Characteristics of the 86 patients with cirrhosis are shown in Supporting Table S3. Six-month cumulative risk of death was similar between the two groups (Fig. 1B).

In addition, in order to evaluate the impact of abdominal surgery on overall outcome of patients with INCPH, we compared 3-year liver transplantation–free survival of patients with INCPH who had abdominal surgery within 3 years after diagnosis of INCPH (29 patients from the present study) to that of patients with INCPH but without abdominal surgery (n = 82). Three-year transplant-free survival was similar between the two groups (Fig. 1C).

Overall Postoperative Unfavorable Outcome

Overall postoperative outcome was unfavorable in 22 (50%) patients. History of ascites was associated with an unfavorable outcome (Table 4). As extrahepatic conditions related with INCPH and serum creatinine levels fell short of statistical significance and as we have previously reported that these features are associated with a poor outcome after TIPSS in patients with INCPH,25 we classified patients according to these items and to history of ascites at surgery. Five percent of the patients with neither extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH nor history of ascites at surgery nor serum creatinine ≥ 100 µmol/L had an unfavorable outcome (Fig. 2). Only one patient without these criteria had an unfavorable outcome; this patient had postoperative bleeding after cholecystectomy, requiring reintervention under local anesthesia. By contrast, 64% of the patients with two or more features had an unfavorable outcome.

Influence of Portal Decompression on Postoperative Outcome

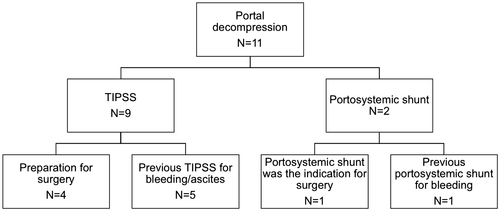

Eleven patients had portal decompression prior to, or at the time of, surgery (Fig. 3). In 1 of these patients, portosystemic shunt was the indication for surgery, with concomitant splenectomy (Table 2 and Fig. 3). In the 10 remaining patients, median time between portal decompression and surgical intervention was 4.0 (0.3-44.6) months.

In order to assess the effect of portal decompression on the outcome after surgery, we compared the outcome of the 10 patients who had either TIPSS or portosystemic shunt before surgery to the 33 patients who did not (Supporting Table S8). Except for beta-blockers, baseline characteristics did not differ between the two groups. Postoperative outcomes did not differ between patients with previous TIPSS or portosystemic shunt and those without. Of patients who had a previous TIPSS or surgical portosystemic shunt, 1 had a grade ≥ 3 complication within 1 month after surgery (leakage) and 3 had at least one portal hypertension–related complication within 3 months after surgery (1 had decompensation of ascites, 1 decompensation of ascites and encephalopathy, and 1 acute kidney injury). When included in the univariate Cox regression analysis, portal decompression was not associated with either portal hypertension–related complications (HR [95% CI], 0.746 [0.212-2.618]; P = 0.647) or death within 6 months after surgery (HR [95% CI], 1.153 [0.120-11.088]; P = 0.902). Furthermore, portal decompression was not associated with an unfavorable outcome after surgery (HR [95% CI], 0.874 [0.322-2.372]; P = 0.792).

Discussion

This study, focusing on the outcome of patients with INCPH undergoing abdominal surgery, shows that 6-month mortality after surgery was 9%, affecting patients with comorbidities and/or serum creatinine level ≥ 100 µmol/L. Patients without extrahepatic conditions related to INCPH, without increased serum creatinine, and without a history of ascites at surgery had a favorable postoperative outcome. Although this study gathered the largest number of patients with INCPH undergoing abdominal surgery reported to date, interpretation of the results should take into account that number of patients included remained limited, that the study was retrospective, and that various surgical interventions were performed. Given the rarity of the disease, conducting a prospective study seems, however, not realistic.

The main information derived from this study is that mortality of patients with INCPH undergoing abdominal surgery is higher than that reported in the general population. We observed a 6-month mortality rate of 9% (95% CI, 1%-17%) in patients with INCPH, while in the general population, in-hospital or 1-month mortality after abdominal surgery ranges from 3% (95% CI, 0.4%-7%) to 12% (95% CI, 7%-18%).34-36 We observed that the 6-month mortality rate of patients with INCPH did not differ from that of patients with cirrhosis, matched for ascites, who underwent abdominal surgery between 2005 and 2016.17 It should, however, be noted that mortality of patients with cirrhosis in this cohort was lower than previously reported.7, 10, 30-32 Indeed, in patients with cirrhosis, reported mortality after surgery ranges from 7% (95% CI, 2%-12%) to 30% (95% CI, 15%-44%)7, 8, 30, 32 at 1 month, 30% (95% CI, 24%-36%) at 3 months, and 54% (95% CI, 47%-61%) at 1 year.31 This lower mortality observed in patients with cirrhosis may be related to a better selection of candidates for abdominal surgery and to the fact that these procedures were performed in tertiary centers. This outcome of patients with INCPH after surgery echoes the overall survival of patients with INCPH outside the surgical setting, known to be intermediate between the general population and patients with cirrhosis.23 In the present study, comorbidities were the main drivers of postoperative mortality as death within 6 months after surgery was restricted to patients with age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 6 or with serum creatinine ≥ 100 μmol/L before surgery. This finding is in line with the natural history of INCPH, where half the mortality is accounted for by extrahepatic comorbidities,22-24 as well as with the outcome after TIPSS placement where mortality is associated with serum creatinine and the presence of extrahepatic conditions associated with INCPH.25 Interestingly, transplant-free survival after INCPH diagnosis was similar in patients who did and did not undergo abdominal surgery during follow-up, suggesting that, in selected patients managed in expert centers, surgery does not have a deleterious impact on the natural history of INCPH. We did not find any association between the type of intervention and postoperative outcomes but cannot rule out a lack of power due to the limited sample size.

The second major finding of the present study was that portal hypertension–related complications, especially ascites, were the most frequent, occurring within 3 months after surgery in 36% and 26% of the patients, respectively. Portal hypertension–related complications increased the length of hospital stay, and 3/16 (19%) required a TIPSS after surgery for refractory ascites or variceal bleeding. However, portal hypertension-related complications were transient in most patients. These results suggest that portal hypertension per se should not be regarded as a definite contraindication for abdominal surgery in patients with INCPH.

De novo PVT occurred in 5 (11%) patients after surgery. Interestingly, PVT following splenectomy was 10-fold more frequent than following other surgeries. Reported rates of PVT following splenectomy range between 17% (95% CI, 13%-21%) and 36% (95% CI, 17%-55%) in patients with cirrhosis37, 38 and 54% (95% CI, 46%-61%) in patients with benign hematologic disorders.39 In the present study, the incidence of PVT was similar to that of patients without cirrhosis because PVT was observed in 50% (95% CI 9%-90%) of the patients with INCPH and splenectomy. Four cases of PVT were diagnosed within 1 month after surgery. Recanalization occurred in 60% of the patients. These findings suggest that routine ultrasound examination at 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months after surgery would allow early detection of PVT, especially after splenectomy.

Infections within 1 month after surgery were common, being observed in 34% of the patients. This figure is in the same range as estimates of postoperative infections after abdominal surgery in patients with cirrhosis and higher than in the general population (29% [95% CI, 21%-36%] and 13% [95% CI, 12%-14%], respectively; P < 0.001).40 In cirrhosis, the risk of infection is likely related to altered innate and adaptive immunity and to increased bacterial translocation.41 In patients with INCPH, susceptibility to infection may be related to portal hypertension but also to extrahepatic conditions associated with INCPH, namely immunological disorders and HIV infection. Bleeding occurred within 1 month in 10 (22%) patients and was associated with administration of anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents. This high incidence is reminiscent of the frequent bleeding episodes reported in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome undergoing invasive procedures while receiving anticoagulation therapy.42

In the present study, we identified a group of patients having an unfavorable outcome, namely those with an extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH, elevated serum creatinine, and/or significant ascites before surgery. By contrast, only 5% of the patients with neither an extrahepatic condition associated with INCPH nor elevated serum creatinine nor significant ascites before surgery had an unfavorable outcome. These simple features could be helpful in making a decision for abdominal surgery with the appropriate information provided to the patient on the risks of the intervention. Due to the retrospective and uncontrolled design of the study, we could not evaluate the survival benefit of surgery (versus no intervention), taking into account the indication of surgery, the severity of INCPH, and extrahepatic comorbidities.

In patients with cirrhosis, the experience of preemptive TIPSS placement before surgery is limited to small, retrospective studies.12-17 A limited number of studies compared patients with cirrhosis with preserved or moderately impaired liver function who had preoperative TIPSS to patients who underwent elective surgery without preoperative TIPSS. Outcome after surgery was similar between patients who had those who did not have a preoperative TIPSS.15, 17 In the present study, portal decompression was not associated with postoperative outcome after surgery. However, the present findings are insufficient to draw any firm conclusion for or against preemptive portal decompression before surgery in patients with INCPH. Indeed, TIPSS was placed as a preparation for surgery in only 4 patients; in the 5 remaining patients, TIPSS had been previously inserted for other reasons, with sometimes a broad interval of time between TIPSS insertion and surgery. Larger dedicated studies are thus needed to address this important question.

In conclusion, in this study, we observed that patients with INCPH were at high risk of major surgical and portal hypertension–related complications when they harbored extrahepatic conditions related to INCPH and/or increased serum creatinine and/or a history of ascites. Comorbidities and higher serum creatinine were significantly associated with 6-month mortality. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of each type of surgery on the natural history of INCPH and the influence of TIPSS on postoperative outcome.

Acknowledgment

We thank Nicolas Drilhon, Héloïse Giudicelli, Marie Lazareth, Djalila Rezigue, Shantha Valainathan and Kamal Zekrini for their help in identifying the patients and collecting the data and Prof. Valérie Paradis for reviewing liver biopsy samples.