A Call to Standardize Definitions, Data Collection, and Outcome Assessment to Improve Care in Alcohol-Related Liver Disease

Abstract

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is highly prevalent and appears to be increasingly reported with worsening mortality; thus, optimizing care in this patient population is imperative. This will require a multidisciplinary, multifaceted approach that includes recognizing alcohol use disorder (AUD) and existing treatments for AUD. We must also acknowledge the full spectrum of ALD clinically and histologically. For example, our current clinical definitions of alcohol-related hepatitis (AH) do not address that >95% of severe AH occurs in the setting of cirrhosis with <60% of liver explants having hepatitis. Given that the majority of ALD studies rely on clinical diagnosis and lack pathologic confirmation, prior data on the efficacy of medical treatment or use of transplantation are likely limited by intertrial and intratrial heterogeneity. Added limitations of the current field include the inconsistent reporting of relapse with the use of varying definitions and unreliable assessments. Moreover, studies fail to consistently capture the data variables that likely influence the main outcomes of interest in this population—mortality and relapse—and a global effort to create a standardized data collection tool moving forward could help effectively and efficiently aid in the advancement of this field. Conclusion: To optimize patient care and make best use of a limited resource, a systematic change in the approach to research in this population must be undertaken that creates consistent definitions for use in future research to generate reliable and reproducible results. With this in mind, we concisely reviewed the literature to summarize the current state of treating and managing ALD, the heterogeneity in definitions, and the significant opportunities for clinical and research improvement.

Abbreviations

-

- AH

-

- alcohol-related hepatitis

-

- ALD

-

- alcohol-related liver disease

-

- AUD

-

- alcohol use disorder

-

- DSM-V

-

- fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

-

- EtG

-

- ethyl glucuronide

-

- P-Eth

-

- phosphatidylethanol

-

- SAH

-

- severe AH

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is a leading cause of liver failure, is increasing in prevalence,1 and is a leading cause of mortality.2 ALD occurs in the setting of underlying alcohol use disorder (AUD) and broadly encompasses a pathological and clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic steatosis to acute alcohol-related hepatitis (AH) to decompensated cirrhosis with or without hepatocellular carcinoma.3 Current medical interventions are of limited efficacy and focus on the treatment of AH. For patients with cirrhosis without AH or patients with AH who fail to improve, consideration of liver transplant may be the only effective option. Given the limited treatment options and rising burden of disease with increasing mortality, optimizing care in this population is imperative, but concern exists for future progress given the significant methodological deficiencies that remain after decades of ALD research.

Previous publications on ALD suffer from lack of standardization. These publications often fail to recognize and define AUD, which is different from quantification of drinks, and do not account for concurrent medical treatment of AUD.4, 5 Studies investigating ALD often use heterogeneous clinical definitions.6, 7 Although this may improve with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) AH Consortia recommendations for defining the study of AH,8 future studies outside of the population with AH lack guidance. Reliance on clinical definitions also appears to be of limited accuracy.4 Additionally, a main outcome of interest posttransplant, alcohol relapse, is heterogeneously defined and variably assessed.4, 5 Further limitations include incomplete data collection, preventing the ability to control for variables that likely influence the main outcomes of interest in this population—mortality and relapse.4, 5 Given these concerns, current research and future efforts need to focus on recognizing and understanding our current data gaps and limitations and the development of universal standardized definitions so that accurate, significant advances can be made in the study of ALD.

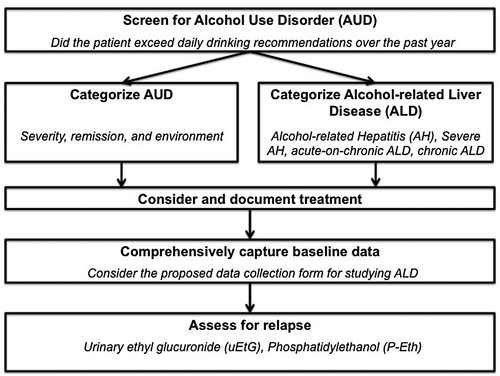

This major shift in approaching research in the population with ALD must occur on a nationwide and global scale across institutions. A multidisciplinary and multifaceted approach would include (1) accounting for AUD, (2) accurately categorizing ALD, (3) defining relapse and its assessment, and (4) creating a uniform data collection tool.8 Below we concisely review the literature to date and make recommendations on each of these four points, with a proposed flow chart for approaching patients with ALD (Fig. 1) and a proposed data collection tool (Table 1).

| General demographics |

| Age |

| Sex |

| Race |

| Ethnicity |

| Existing medical comorbidities |

| Reported use of medications associated with drug induced liver injury* |

| Additional contact (phone number or e-mail of a family member or close friend) |

| AUD |

| Current severity (mild, moderate, severe)† |

| Age at onset of drinking |

| Duration of heavy drinking (in years) |

| Number of daily standard drinks (12 oz of beer, 8-9 oz of malt liquor, 5 oz of wine, 1.5 oz of hard liquor) |

| Frequency of binge drinking |

| Date of last drink |

| Length of abstinence (years) |

| Remission (early or sustained)‡ |

| Environment (controlled or uncontrolled)§ |

| Preferred beverages |

| History of prior alcohol-related decompensating events (hospitalizations) |

| Prior outpatient treatment for AUD (yes/no) |

| Number of prior inpatient treatments for AUD |

| History of alcohol-related legal issues |

| Alcohol relapse |

| Following AUD treatment (yes/no) |

| If yes, how many times? |

| Following diagnosis of AH |

| If yes, how many times? |

| Number of prior nuclear family members with a history of AUD |

| Number of prior nuclear family members with a history of ALD |

| Socioeconomic factors |

| Highest level of education completed |

| Household income |

| Employment status |

| Relationship status |

| Living situation |

| Psychiatric factors |

| Psychiatric comorbidities |

| Illicit IV drug use (current/prior/never) |

| Illicit non-IV drug use (current/prior/never) |

| Nicotine addiction (current/prior/never) |

| ALD |

| Laboratory evaluation |

| Standard liver tests|| |

| Complete blood count with differential |

| Basic metabolic profile |

| Metabolic syndrome¶ |

| Evaluation for other causes of liver disease# |

| Clinical spectrum (AH, SAH, acute-on-chronic ALD, chronic ALD, hepatocellular carcinoma due to ALD) |

| Abdominal ultrasound/CT/MRI suggestive of cirrhosis (yes/no) |

| Elastography (in kilopascals) |

| Histologic findings |

| Cirrhosis present |

| Steatosis without hepatitis present |

| AH present |

| Existing scores |

| Child-Turcotte-Pugh score |

| MELD |

| Maddrey discriminant function |

| Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis score |

| Lille score in steroid treated patients |

| Complications of chronic liver disease |

| Ascites (current/prior/never) |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (current/prior/never) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (current/prior/never) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (current/prior/never) |

| Hepatorenal syndrome (current/prior/never) |

| Varices (current/prior/never) |

| History of bleeding |

| Treatment |

| AUD |

| Medical |

| Behavioral |

| ALD |

| Medical |

| Transplant |

| Follow-up |

| Lost (yes/no) |

| Complete (yes/no) |

| Length |

| Relapse |

| Assessed (yes/no) |

| Standardized time interval (yes/no) |

| Frequency |

| Standardized interview (yes/no) |

| Breathalyzer (yes/no) |

| Serum alcohol (yes/no) |

| Urinary EtG (yes/no) |

| Hair EtG (yes/no) |

| P-Eth (yes/no) |

| Quantified (grams per day) |

| Daily use vs. start/stop |

| Length of drinking |

| Actively drinking at study end date (or death) |

| Mortality |

- The proposed tool expands on the data collection tool recommended by the NIAAA AH Consortia for research investigating AH.8 This more comprehensive tool is meant to be used in studying ALD, regardless of the presence of AH.

- * Providers should specifically ask about medications that patients may not identify as medications. We agree with suggestions made by Crabb et al.—“over-the-counter medications, herbals, dietary supplements, and probiotics.”8

- † The DSM-V recommends that providers specify the severity of AUD as mild (presence of two to three symptoms), moderate (presence of four to five symptoms), or severe (presence of six or more symptoms).9

- ‡ The DSM-V recommends documentation of the presence of remission, categorized as early (>3 months but <12 months) or sustained (>12 months).9

- § The DSM-V recommends specifying the presence or absence of a controlled environment, (i.e., an alcohol restricted environment).9

- || Inclusive of laboratory tests detailed by Crabb et al.—“aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, bilirubin, international normalized ratio, albumin, total protein.”8

- ¶ Inclusive of laboratory tests detailed by Crabb et al.—“high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, cholesterol, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c.”8

- # Inclusive of laboratory tests detailed by Crabb et al.—“hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus serology, antinuclear antibody, iron, ferritin, iron binding capacity.”8

- Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; IV, intravenous; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Recognizing and Defining AUD

AUD, when diagnosed according to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) put forth by the American Psychiatric Association, is highly prevalent.9 AUD is defined by meeting two of 11 possible criteria over a 12-month period that suggest alcohol use causes significant harm or suffering.9 Simple, effective screening for AUD can be achieved with the single question assessing how many times over the past year patients exceeded daily drinking recommendations (four and three drinks for men and women, respectively), with one or more occurrences being positive.10 The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test can be used when more specificity is needed.11 The DSM-V recommends that providers specify the severity of AUD as mild (presence of two to three symptoms), moderate (presence of four to five symptoms), or severe (presence of six or more symptoms) and document the presence of remission, categorized as early (>3 months but <12 months) or sustained (>12 months).9 The DSM-V also recommends specifying the presence or absence of a controlled environment (i.e., an alcohol-restricted environment).9

Following these criteria, the literature suggests health care disparities within AUD. The estimated lifetime prevalence of AUD is 29.1%, with greater severity for men, those of white or Native American race, younger adults, previously married or never married respondents, and those in the lowest income level.12 Additionally, patients with AUD are more likely to have other drug use disorders, psychiatric comorbidities, and personality disorders with worsening quality of life when a higher proportion of the 11 possible criteria for AUD are met.9 ALD, which develops in the context of existing AUD, consistently lacks the comprehensive reporting of AUD and these demographics for the studied population.

Additionally, although less than 20% of AUD is treated, effective treatments exist, and the prevalence of patients with ALD receiving medical treatment of AUD is unknown.12 Treatments range from “brief interventions” to daily medications with or without other behavioral therapies.13 A recent systematic review found that interventions reduce drinks per week, drinking beyond recommend limits, and heavy-use episodes and increase abstinence.11 Approved medications for AUD include acamprosate, disulfiram, and naltrexone.11, 14 Newer behavioral therapies involve counseling interventions or specific strategies delivered in person at office visits or electronically as well as more traditional therapies such as Alcoholics Anonymous and rehabilitation facilities.11, 14 The literature assessing transplantation for ALD generally fails to report concurrent treatment of AUD, but given the data supporting the efficacy of medication and behavioral treatment, it is imperative to treat the underlying AUD and assess its impact on ALD study outcomes, particularly relapse.

Overall, AUD is an entity within ALD, defined according to the DSM-V. Within AUD, health care disparities and effective treatment options exist, which even the most recently reported studies4, 5 fail to capture. Future approaches to care and research in this population must involve a multidisciplinary approach, with transplant hepatologists, addiction specialists, and psychiatrists working together across institutions to develop a protocol based on the best clinical evidence. The protocol should then undergo frequent scheduled testing, with updates, to ensure clinical relevancy and efficacy.

Accurately Categorizing ALD

ALD occurs on a spectrum with proposed definitions that only capture a part of the spectrum (AH) and have limited applicability in prospectively designed clinical trials. Although standard definitions for studying AH have been proposed in clinical trials as definite (clinically diagnosed and biopsy proven AH), probable (clinically diagnosed AH without confounding factors), and possible (clinically diagnosed AH with confounding factors)8 (Supporting Table S1), no inclusion or exclusion criteria exist for the spectrum of ALD outside of AH. Furthermore, the AH definitions exclude subjects with Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores >30 or a Maddrey discriminant function of >60. Although Lee et al. were able to apply the definitions to their retrospective cohort, the majority of their population would have been excluded from a prospective trial.4 Therefore, formal clinical definitions are lacking outside of AH, and reconsideration of inclusion and exclusion criteria is necessary to apply the AH Consortia criteria to prospective cohorts evaluating severe AH (SAH).

Additionally, literature to date suggests that clinical diagnoses associate poorly with underlying histologic findings. Although the AH Consortia suggest that a clinical diagnosis of probable AH will accurately predict biopsy-proven AH in >90% of cases,8 when Lee et al. applied the AH Consortia definitions, despite 79% meeting AH inclusion criteria clinically, on explant, 96% of their population had cirrhosis, with only 59% having steatohepatitis and 41% having cirrhosis alone with no steatohepatitis.4 More recently, a retrospective study suggested a correlation of leukocyte count with AH, but this study was only inclusive of patients with a Maddrey discriminant function >32, and the sensitivity decreased to 59% in the validation cohort.15 In addition, a prospective study investigating non-AH ALD found that only 26% of the high-risk cohort for cirrhosis had histologically present cirrhosis.16 These findings suggest current limitations of the proposed AH Consortia definitions of probable AH and a need for more accurate predictors of AH and fibrosis in patients with ALD.

The poor association of clinical predictors with underlying histologic findings may explain the varying results of treatment efficacy in trials studying clinically diagnosed AH and the heterogeneity observed in meta-analyses. Society guidelines strongly recommend with moderate supporting evidence the use of steroids in SAH, conditionally recommend with low supporting evidence against the use of pentoxifylline in SAH, and conditionally recommend with very low supporting evidence nutritional supplementation for AH.3 The guidelines recognize that therapies with potential efficacy for AH may include N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor.17, 18 Although a network meta-analysis suggested efficacy of pentoxifylline, steroids, and combination therapy of steroids with either NAC or pentoxifylline in comparison with placebo in a group of patients with SAH, there was significant heterogeneity.19 The heterogeneity suggests that fundamentally different studies are being combined, which appears largely accounted for by variability in the individual studies’ inclusion criteria. To optimize care, future trials investigating pharmacologic therapies should strongly consider limiting inclusion to patients with pathological specimens available, and all clinical trials publishing on ALD should report concurrent use of potentially disease-modifying medications, particularly steroids for AH and presence and management of complications of cirrhosis, as this may have effects on study outcomes.

Until clinically defined ALD clearly correlates with histological findings or better noninvasive markers exist, particularly for AH, future trials should consider carefully defining the cohorts at both the clinical and, where possible, histologic level. Although performing liver biopsies is uncommon in current clinical practice, particularly in the United States, and is costly with a risk of harm, continuing to rely on inaccurate clinical predictors and conducting heterogeneous, nonreproducible studies that fail to move the field forward is unacceptable. To combat the costs and risks associated with liver biopsy, study design that enrolls the necessary sample size to maximize sensitivity and minimize patient risk will be imperative.

Defining Relapse and Assessment

Within the ALD literature, relapse has been defined in a variety of ways, and standardization is needed to understand treatment effects, particularly the relapse risk in liver transplantation in patients with short and long pretransplant abstinence periods. Although some studies reported relapse rate, they failed to clearly define the methods of assessment of alcohol use.7 Among studies that do define relapse, definitions range from any alcohol consumption to specifying the frequency, type, and amount of alcohol consumed,20 further categorizing this into relapse/continued consumption versus slips4 or other categories.5 Prospective study of a population with SAH over a 5-year period suggests that alcohol relapse has an associated mortality for alcohol consumption (>30 g/day) at 6 months in comparison with abstinent patients (hazard ratio, 3.9) that increases with greater consumption.21 Findings from a retrospective study in patients with AH similarly report improved survival in abstinent patients in comparison with those with relapse.22 Although relapse can be difficult to define, given the dose-dependent relationship of relapse with mortality, defining relapse as any alcohol use and then quantifying the consumption of alcohol while considering sustained alcohol use versus slips may be a reasonable starting approach.

Assessing relapse can be difficult, and techniques range across studies; recognition of this heterogeneity is required when interpreting study data. Prior studies used only interviews20 and interviews in combination with random, selective, or routine alcohol testing either through blood or urine testing.4, 7, 21 Prospective comparison of urinary ethyl glucuronide (EtG) with other indirect markers of alcohol consumption were compared in liver transplant candidates and recipients, finding alcohol consumption in 30.6% of patients, with urinary EtG being the strongest marker of consumption.23 Other potential markers to use include hair EtG and serum phosphatidylethanol (P-Eth), the latter of which appears to have better sensitivity and specificity than other existing options.24 Although relapse can be difficult to capture, the existing literature suggests that routine EtG evaluation or serum P-Eth most accurately capture relapse.

Creating a Uniform Data Collection Tool

Managing and treating patients with ALD is quite complex, and many known variables affect the main outcomes studied in this population—survival and relapse—and need to be accounted for and collected systematically. These include variables associated with AUD; severity of liver disease on the clinical and, when available, histological spectrum; and treatments of AUD and ALD. Although the prior AH Consortia put forth recommendations regarding a common clinical data set,8 there remain opportunities for improvement. We suggest adding the following additional data collection fields: employment status, living situation, medical comorbidities, categorization of AUD according to the DSM-V,9 liver disease severity classified on the clinical spectrum as well as using imaging modalities and existing scoring systems, accounting for complications of chronic liver disease, behavioral management of AUD, follow-up details, and relapse (Table 1). Additionally, in the posttransplant population, histologic characterization of all explants, graft dysfunction, and retransplantation should be collected, as well as protocol assessment of relapse by laboratory work and possibly posttransplant biopsies to assess recurrent subclinical ALD. We anticipate that by universally capturing these data, more clear and accurate conclusions will be drawn that will advance the field and optimize care.

Conclusions

The burden of ALD is rising, and evaluation of studies investigating various treatments ranging from medications to transplantation are limited in conclusive findings, likely because of the use of unstandardized, heterogeneous definitions of the cohorts studied as well as outcomes reported, particularly relapse. Additionally, incomplete data collection prevents controlling for variables known to be associated with the outcomes of interest. To move the field forward, eliminate bias, and optimize care for this highly prevalent disease, we must recognize the limitations of conclusions drawn from existing data and address these deficiencies prospectively moving forward. To do this, we recommend taking steps to create a global consortium with standardized definitions and data collection tools based on the existing data that are systematically reevaluated and updated as the field advances.