Hepatitis C in Patients With RenalDisease: A Deeper Dive Into the KDIGO Guideline

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Terrault consults for Dova Pharmaceuticals. She received grants from Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb Merck and AbbVie.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has contributed to significant morbidity and mortality in persons with renal disease. Given recent advances in therapies for HCV, it is timely to have updated guidance on HCV management in patients with renal disease, both those on dialysis and after kidney transplantation (KT). The just-published Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice guideline1 addresses prevention, monitoring, and treatment of HCV in patients with renal disease, including those on dialysis and KT recipients.

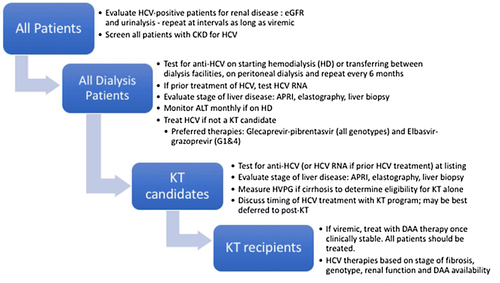

The first step in the HCV care cascade is the identification of HCV-infected persons. The prevalence of HCV among dialysis patients is higher than the general population, reflecting higher risks for HCV acquisition from blood transfusion and iatrogenic sources. Reduced use of blood transfusions plus improved infection control measures have significantly reduced incident HCV infections among dialysis patients, though outbreaks still occur related to lapses in infection control practices. The KDIGO guideline on monitoring of dialysis patients reflects efforts to identify new infections early, given that these may represent breaches in infection control that require quick remedy. All persons starting dialysis need to be tested. In all instances, hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV) followed by HCV-RNA testing is preferred, though for those starting hemodialysis (HD) or transferring between facilities (Fig. 1), HCV-RNA testing alone is an option, presumably to detect window infections. Also, for those previously treated and cured of HCV, HCV RNA rather than anti-HCV is recommended. Additional recommendations are to repeat testing every 6 months with anti-HCV (if previously negative) or HCV RNA (if previously anti-HCV positive and cured). A weaker recommendation for alanine aminotransferase (ALT) testing monthly is made in the HD group—to detect acute HCV infections occurring between the 6-month testing periods. Given that ALT elevation occurs typically by week 4 after exposure and preceding anti-HCV seroconversion, this is a reasonable approach. However, although testing all persons with any elevation of ALT will have high sensitivity for acute HCV infections, specificity is very low and results in substantial increases in HCV testing, especially if the newly recommended upper limits of normal (ULNs) for ALT are used (>29 to 33 IU/L for males, >19 to 25 IU/L for females).2 Case definitions of acute HCV have used ALT thresholds varying from 2.0 to 2.5 to 10 times ULNs, and thus a 2.0- to 2.5-fold increase in ALT above normal may be a better threshold to trigger HCV testing if monthly ALT monitoring is used. For patients on dialysis with chronic HCV infection, ALT levels tend to be lower than nondialysis patients, and thus, if used as an adjuvant to anti-HCV screening, the newly recommended ULNs for ALT should be applied.

The KDIGO guideline recommends all anti-HCV–infected persons be screened for kidney disease with urinalysis and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and that viremic patients undergo serial testing (Fig. 1),2 but this is not graded, highlighting the lack of data to support this recommendation. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) HCV Guidance does not recommend these assessments in every patient.6 The cost of a urinalysis is not high, but the question of whether this leads to unnecessary additional testing needs to be considered. A more selective approach seems more reasonable. Determination of eGFR is needed to confirm suitability to use of sofosbuvir-based therapy. Evaluating for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and/or cryoglobulinemia is relevant if baseline creatinine is abnormal or if there are any symptoms to suggest vasculitis. Additionally, in states that have restrictive policies for HCV treatment, identification of extrahepatic manifestations may lead to approval in patients who otherwise might not qualify.

The KDIGO guidance recommends assessment of fibrosis severity in every HCV-infected patient with CKD (Fig. 1). This is relevant in treatment planning and follow-up after HCV eradication. Similar to other guidelines,6 KDIGO advocates for use of noninvasive testing, with liver biopsy reserved for cases where noninvasive results are discordant or when other causes of liver disease are suspected. However, data on the accuracy of noninvasive testing in dialysis patients are limited. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) and Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) have been shown to be less accurate in dialysis patients.4 Elastography is more accurate than serum panels in excluding advanced fibrosis (AF), but the influence of volume status needs to be minimized. Elastography done the day after dialysis and with at least an 8-hour fast yielded results with high area under the receiver operating characteristic curve values compared with liver biopsy in one study.5 Since the main concern is overestimation of fibrosis severity by noninvasive tests, no further testing is needed if noninvasive tests indicate non-AF. However, if AF is found on noninvasive testing, proceeding to liver biopsy is important to exclude the presence of cirrhosis. Accurate staging is critical for defining need for surveillance for liver cancer and other complications of AF, but also in planning KT.

The KDIGO guideline suggests (not recommends) measurement of hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) in those with AF who are being considered for KT. Given that this may not be the routine in many programs, it is a noteworthy addition to the guideline. Studies have shown outcomes of KT recipients with compensated cirrhosis (CC) and an absence of portal hypertension (PHT) to be similar to those without cirrhosis.6 The KDIGO guideline recommends combined liver-kidney transplant for those with cirrhosis and severe PHT defined as HVPG ≥10 mm Hg and/or decompensation. For patients with CC but HVPG beyond criteria for KT alone, it is worth considering whether HCV eradication with antiviral therapy (AVT) may reduce the HVPG to a level allowing KT alone. Studies in non-ESRD (end-stage renal disease) patients with CC show that 40% of persons with HVPG 10-15 mm Hg pretreatment attain a reduction in HVPG to <10 mm Hg after sustained virological response (SVR). In contrast, no patient with baseline HVPG ≥16 mm Hg achieved a reduction to <10 mm Hg with treatment. The likelihood of reversal of PHT is related to the baseline HVPG, severity of cirrhosis (less likely if Child-Pugh B vs. A cirrhosis), and length of follow-up post-SVR.7 As highlighted below, the decision to treat HCV in patients who are candidates for KT is a complex one, but the KDIGO guideline appropriately endorses the need for accurate information on stage of liver disease to guide best decisions.

Turning to treatment, the KDIGO guideline recommends all patients with CKD be evaluated for treatment (Fig. 1). This decision should be made in concert with the KT team. This is particularly relevant in KT programs using HCV-positive donors. HCV-RNA–positive donors can provide an accelerated pathway to KT for HCV-infected dialysis patients. For example, at our center in Northern California where the median waiting time for a KT is 8 years, an HCV-infected wait-listed patient who accepts an anti-HCV viremic donor reduces the waiting time to less than a year. Thus, for CKD patients with HCV on the waiting list, HCV treatment should not be undertaken until the use of HCV-positive donors has been discussed. For these patients, deferral of HCV treatment until posttransplant is best, and indeed, AVT options are greater posttransplant when eGFR is restored. For those who are ineligible for KT or without access to HCV-positive donors, treatment should be a high priority. With the approval of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir in 2018, the first pangenotypic regimen for patients with eGFR levels <30 min/mL, including those on dialysis, became available. This option together with elbasvir-grazoprevir (for genotypes 1 and 4 only) are the two preferred therapies per the IDSA-AASLD guidance.3 The KDIGO guideline predated the approval of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir and thus do not mention this important addition. Sofosbuvir-based therapies are not recommended in patients with eGFR less than 30 mL/min. However, encouraging data are accumulating regarding the safety of sofosbuvir in persons with ESRD.8 That said, use of sofosbuvir-inclusive regimens should be limited to exceptional circumstances, such as the patients with decompensated cirrhosis and renal failure or persons who failed previous DAA therapies. Overall, the last year has seen been transformative in terms of treatment of ESRD patients, with safe and highly effective DAA therapies now available for all HCV genotypes.

With the goals of eliminating hepatitis C by 2030, the dialysis and KT populations are key populations for testing, treatment, and prevention. The KDIGO guideline is an excellent resource and, coupled with the updated IDSA-AASLD guidance, provides clinicians with a comprehensive guide to caring for this special patient population. With application of these testing and treatment recommendations to ESRD and KT recipients with HCV, a reduced burden of infected persons and lower mortality related to HCV-associated renal and liver diseases can be anticipated.