Regression of HCV cirrhosis: Time will tell

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Supported by the Yale Liver Center (National Institutes of Health grant P30 DK34989).

Abbreviations

-

- CSPH

-

- clinically significant portal hypertension

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- HVPG

-

- hepatic venous pressure gradient

-

- LSM

-

- liver stiffness measurement

In patients who have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV), one of the goals of viral elimination is to prevent progression across the different stages of disease, thereby preventing the development of clinically relevant outcomes. Viral elimination in chronic hepatitis C has been shown to prevent progression to more advanced stages of fibrosis/cirrhosis. Furthermore, in patients with compensated cirrhosis, viral elimination has been shown to prevent or delay the development of varices, decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In fact, these patients have been shown to have a life expectancy similar to that of the general population.

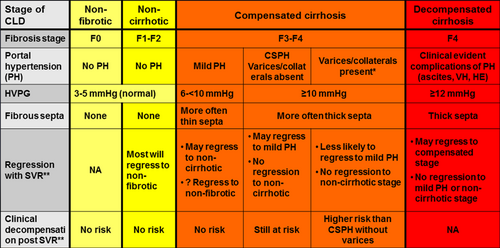

However, regression of the disease is also an important outcome—perhaps even more important—and this will depend on the stage of chronic liver disease at the time of initiation of antiviral therapy (Fig. 1).

In chronic liver disease with only mild/moderate fibrosis, one assumes that because fibrogenesis and vascular/parenchymal alterations that lead to cirrhosis are ongoing and incomplete, viral elimination (in the absence of concomitant injurious agents/conditions) will eventually lead to regression to a normal liver.

In the sickest patients, those with decompensated cirrhosis, regression would be to a compensated stage, as demonstrated in patients with decompensated HCV cirrhosis in whom HCV elimination has led to recompensation (that is, return to a compensated stage) and delisting from the transplant list.1 However, in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, stromal and vascular alterations in the liver are likely irreversible, and it would be essentially impossible for the liver to regress to a noncirrhotic stage.2

It is patients with compensated cirrhosis in whom regression to a noncirrhotic stage is a possibility. Regression of fibrosis in HCV-compensated cirrhosis has been described after viral elimination with interferon-based therapy.3 What is still undefined is the subgroup of patients with compensated cirrhosis in whom regression to a noncirrhotic stage is possible and the substage at which regression will be unlikely (i.e., the point of no return) and how to determine whether such regression has occurred not only histologically but also clinically (i.e., eliminating risk of cirrhosis-related clinical events). In a position paper published in Hepatology that correlated the clinical, hemodynamic, histological, and biological aspects of chronic liver disease/cirrhosis, we postulated that the stage at which compensated cirrhosis may not be reversible is the stage of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH), defined as a hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) of at least 10 mm Hg2 (Fig. 1). This was based on evidence showing that, in patients with compensated cirrhosis and mild portal hypertension (HVPG >5 but <10 mmHg), fibrous septa were more frequently thin, whereas in those with CSPH, fibrous septa were mostly thick,4 in a pattern that has been classified as “predominantly progressive”5 and is unlikely to regress. These concepts are being increasingly explored now that therapies for HCV lead to viral elimination in most patients.

In this issue of Hepatology, Mauro et al.6 investigate fibrosis regression in a relatively large group of patients (n = 112) with posttransplant recurrent HCV with at least stage F1 fibrosis (METAVIR system) before therapy and with repeat liver biopsy 12 months after viral elimination. Fibrosis regression (defined by decrease by one METAVIR stage or more) occurred in 67% of patients overall but occurred in a larger percentage (72%-85%) of patients without cirrhosis (F1-F3) compared with patients who had cirrhosis (F4) at baseline, 43% of whom had fibrosis regression. Importantly, regression to a nonfibrotic stage (F0) was observed in 72% of patients with F1 fibrosis, 39% of patients with F2 fibrosis, 15% of patients with F3 fibrosis, and in no patients with F4 fibrosis at baseline.

Of the 37 patients with cirrhosis, 92% remained at F4 fibrosis or decreased to F3 fibrosis—that is, most remained with advanced fibrosis. However, almost half of the patients with cirrhosis in the cohort had a history of decompensation and, when analyzed jointly with compensated patients, they find that prior decompensation, together with the presence of CSPH and thick septa on liver biopsy were predictors of lack of fibrosis regression. This is not at all surprising, because patients who decompensate by definition have CSPH and, as mentioned above, are more likely to have nonreversible thick fibrous septa.2

The question that begs answering but remains unanswered by Mauro et al. is the identification of the subgroup of patients with compensated cirrhosis (i.e., without a history of decompensating events) in whom fibrosis regression occurred as well as the predictors of regression in this specific subgroup of patients. Evidence suggests that the presence of CSPH is the main predictor of lack of regression after viral elimination in these patients. In a recent study that included only patients with CSPH (but that also included patients with decompensated cirrhosis), CSPH persisted in 78% of patients despite viral elimination.7 Studies looking at clinical outcomes demonstrate that decompensation after viral elimination only occurs in compensated patients with pretreatment CSPH8 or in those with pretreatment varices (who have CSPH by definition).9 The study by Mauro et al. further supports this contention by showing, in a subgroup of 25 patients with cirrhosis, a significantly lower pretreatment hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) (median: 7 mm Hg) in patients with regression compared with those without regression (median: 14 mm Hg), and by showing that the lowest baseline HVPG in patients without fibrosis regression was 11.5 mm Hg (i.e., CSPH).

A noninvasive way to detect this point of no return could be through liver stiffness measurement (LSM). Mauro et al. also investigated paired LSM in a subgroup of patients, 34 of them with cirrhosis. In these, LSM decreased more in those with fibrosis regression, and the lowest pretreatment LSM in patients without regression was 25.3 kPa (in line with cutoffs that define CSPH in nontransplanted patients). Parenthetically, posttreatment LSMs below 10 kPa were observed in some patients who remained with advanced fibrosis. Because complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma have been shown to occur in patients with regression to F3 fibrosis and normalization of LSM,3 it is dangerous to assume that LSM can confidently rule out the presence of advanced fibrosis and guide screening strategies, as proposed by the authors.6 With a sensitivity of only 82%, 18% of patients who remain with advanced fibrosis after viral elimination and at risk for complications would not be screened.

Ultimately, cirrhosis-related clinical complications (or lack thereof) are the ones that should define cirrhosis regression. In the study by Mauro et al., clinical decompensation was present in 50% of patients with cirrhosis at the start of treatment, and only 5% remained decompensated after therapy, confirming that regression from a decompensated to a compensated stage occurs after viral elimination, independent of histological fibrosis regression. A tendency for an improvement in survival was also observed in these patients, although again the lack of stratification by stage (Fig. 1) does not allow identification of the subgroup that benefited the most.

In conclusion, the study by Mauro et al. is a step forward in our understanding of the course of chronic liver disease after elimination of the etiological agent. We have learned that, in patients with posttransplantation recurrent HCV, viral elimination (12 months) leads to fibrosis regression in a substantial number of patients (albeit mostly those with noncirrhotic stages) and that patients with cirrhosis (particularly those with clinically significant portal hypertension) are unlikely to regress. This mirrors findings in immunocompetent patients with HCV cirrhosis—although perhaps in patients with posttransplantation HCV in whom fibrosis progression is much faster, regression will also be faster and may occur in an even larger number of patients with histological cirrhosis. Because cirrhosis regression is not only about fibrosis regression but also reversal of vascular and parenchymal abnormalities, which are not assessed by the METAVIR score and could be irreversible,10, 11 the best evidence and definition of regression of cirrhosis will be based on the assessment of long-term clinical outcomes. Further follow-up of Mauro et al.'s cohort with histological, hemodynamic, elastographic, and clinical data, stratified by stage of liver disease, will provide invaluable data toward this definition. Time will tell.

-

Guadalupe Garcia-Tsao, M.D.1,2

-

1Section of Digestive Diseases

-

Yale University School of Medicine

-

New Haven, CT

-

2Section of Digestive Diseases

-

VA-CT Healthcare System

-

West Haven, CT