Investigating the relationships between emotional experiences and behavioral responses amid the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey

Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic produced a complex combination of intense negative emotions among the general public, influencing people's coping reactions toward the pandemic. Yet each discrete emotion may affect people's behaviors in different ways. Unveiling the specific emotion–behavior relationships can provide valuable implications for designing effective intervention programs. Through the lens of the appraisal theory of emotion, we assessed the relationships between negative emotions and pandemic-related behaviors among the Chinese population midst the early outbreak of the pandemic. An anonymous online survey was distributed to mainland Chinese participants (n = 2976), which assessed individuals' emotional states and behavioral reactions to the pandemic. Consistent with the differential appraisal theme underlying each negative emotion as delineated by the appraisal theory, mixed relationships between emotions and pandemic-related behaviors were revealed. Specifically, anxiety was positively associated with behaviors of seeking pandemic-related information, sharing such information, and stockpiling preventive goods, yet, contrary to prediction, anxious people were reluctant to adopt preventive measures, which is maladaptive. Sad people sought information less frequently and exhibited lower intention to stockpile preventive goods; but, opposing prediction, they shared information less frequently. Angry people were more active in sharing information and in stockpiling preventive goods. These findings suggest that public health practitioners can utilize the emotion–behavior relationships to identify the vulnerable individuals who tend to adopt maladaptive coping behaviors, help them address emotional distress, and encourage their adoption of effective coping behaviors.

Abbreviations

-

- CCDC

-

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention

-

- CDC

-

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

- IRB

-

- Institutional Review Board

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

1 INTRODUCTION

The unforeseen outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) in December 2019 has caused 370,572,213 confirmed cases and 5,649,390 deaths worldwide by January 30, 2022 [1], bringing dramatic changes and tremendous impacts on the public's psychological health [2]. People who witness this world-shaking pandemic would experience intense negative emotional reactions [3]. Emotions play a vital role in regulating people's behaviors facing crises like the Covid-19 pandemic [4]. Critically, discrete emotions may affect people's behaviors in different manners [5, 6]. Thus, understanding the relationships between people's emotions and behaviors amid the Covid-19 pandemic can generate valuable insights for intervention services. Yet few prior research has disentangled the emotion–behavior relationships under the Covid-19 pandemic.

Against this backdrop, this research adopted an emotion-focused perspective to comparatively assess the relationships between three commonly experienced emotions in public health crises—anxiety, anger, and sadness—and people's behavioral reactions to the Covid-19 pandemic. Four key pandemic-related behaviors were examined: seeking pandemic-related information, sharing pandemic-related information, adopting preventive health behaviors, and the behavior of stockpiling personal preventive goods, all of which are critical for containing the pandemic and protecting the general public [7, 8].

This research focused on Chinese people who were the very first to witness the outbreak and rapid development of the pandemic, with the first confirmed case identified in Wuhan, China, on January 3, 2020 [9]. The Chinese government rapidly implemented preventive measures to contain the coronavirus disease, including locking down Wuhan city on January 23, 2020, and advising people to follow strict social distancing and home quarantine [10]. This experience was bound to elicit intense negative affective reactions, which would, in turn, affect Chinese people's behaviors in responding to the pandemic.

This research integrates the literature on emotion and on behavioral reactions in public health crises to provide a comprehensive understanding of the emotion–behavior relationship amid the Covid-19 pandemic. The findings enrich the knowledge of the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic and generate practical implications for public health interventions. In the following sessions, related research was reviewed and hypotheses were developed.

2 THEORIZING

2.1 Discrete negative emotions facing Covid-19: anxiety, anger, and sadness

People's emotional reactions to crises like Covid-19 are complex; they may simultaneously experience a combination of distinct emotions [11] and may feel different emotions at different stages of the crisis [12]. The emotional reactions toward crises are dominantly negatively valenced. People reported intense negative emotions, such as anxiety and sadness during the Covid-19 pandemic [4, 13].

Negative emotions are found to exert detrimental consequences on people's behaviors and health [4, 14]. For example, anger increases people's aggressive and risky driving behaviors on the road [14]. Directly relevant to the current research, people who failed to cope with negative emotions elicited by Covid-19 suffered from mental health problems [4]. Yet, negative emotions might as well benefit people. For instance, people who experience negative emotions have a more vivid and accurate memory of an event [15]. We believe the influences of different negative emotions elicited by the Covid-19 pandemic on people's behaviors would be nuanced.

Prior research has established that negative emotions can be disparate [5, 16]. The appraisal theory of emotion proposes that distinct cognitive appraisal meanings and themes elicit discrete emotions and subsequently affect individuals' behaviors in adaptive manners that are consistent with the appraisal themes [6, 17, 18]. In other words, emotion provides information about the environment and how people relate to the environment, motivating people to make adaptive changes.

Anxiety, anger, and sadness are most commonly experienced negative emotions in public health crises [19, 20] and are driven by distinct appraisal themes. Specifically, anxiety is elicited by the appraisal theme of possible adverse outcomes, such as possible failure and loss of control [17]. People who experience anxiety are motivated to alleviate their vulnerability and to enhance their control over the environment [17]. Differently, people experience anger when they encounter a negative outcome or unfairness and attribute it to the wrongdoing of others [21]. Angry people are found to be more risk-seeking [16]. Besides, as angry people tend to hold other people accountable for the negative outcome, they are less other-focused [18]. Finally, the appraisal antecedent of sadness is the loss of reward, such as missing items, the death of loved people, or a broken relationship, usually without a specific target to blame [17]. Hence, sadness motivates reward-seeking behaviors. Besides, different from angry people blaming others for a negative outcome, sad people attribute the adversity to the circumstances rather than other individuals [21], and therefore tend to perform other-focused behaviors [22].

The above-delineated different appraisal themes of anxiety, anger, and sadness suggest that each may encourage different behavioral reactions toward the pandemic. We focus on information-seeking behavior, information-sharing behavior, preventive health behaviors, and stockpiling behavior.

2.2 Emotions and information-seeking behavior

Public health crisis like Covid-19 entails high uncertainty of the situation and encompasses potential risk and danger to people's health. Amid crises, people are instinctively motivated to reduce uncertainty and to obtain control over the situation [23]. This can be accomplished by means of seeking crisis-related information, which helps to alleviate uncertainty, produces comfort, and leads to sound decisions [24].

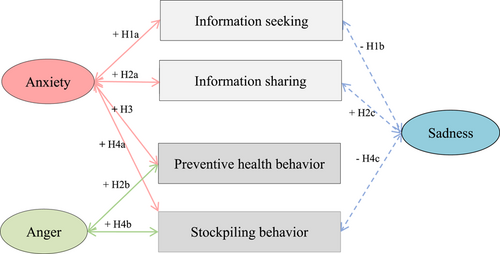

Anxious people perceive high uncertainty over the environment and are motivated to reduce uncertainty and obtain control [25]. Prior research showed that when people face political uncertainty and threat, their anxiety enhances the quantity of information they would like to seek [26], suggesting a positive association between anxiety level and information-seeking behavior. Hence, we predict that facing the Covid-19 pandemic people with strong (vs. weak) feelings of anxiety would seek information more frequently (H1a; see Figure 1 for the summary of hypotheses).

Sad people seek pleasurable information as means of emotion regulation [27]. They avoid the eliciting source of sadness to regulate sadness [28]. During the Covid-19 outbreak, pandemic-related information such as the soaring number of confirmed cases and deaths would elicit intense sad feelings. Hence, sad people are less likely to seek pandemic-related information to avoid the elicitor of sadness. Thus, a negative relationship between people's sadness and information-seeking behavior is expected, such that people with stronger sadness would seek pandemic-related information less frequently (H1b). There is no specific prediction regarding the association between anger and information-seeking behavior. Formally:

H1a: people's anxiety is positively associated with information-seeking frequency.

H1b: people's sadness is negatively associated with information-seeking frequency.

2.3 Emotions and information-sharing behavior

Due to home quarantine and social distancing, Chinese people's isolated living situations limited face-to-face social interactions and enhanced their information-sharing behaviors via online channels, such as social media platforms and blogs [29].

Information-sharing is an important approach to exchanging and obtaining information, and helps alleviate people's anxiety amid crises. For example, prior research showed that physicians' active sharing-information behavior reduces patients' anxiety [30]. Information-sharing behavior among family members waiting for surgical patients helps alleviate their anxiety [31]. Building on these findings, we propose that amid the Covid-19 pandemic anxious people may actively engage in information-sharing behavior (H2a).

Angry people are found to actively share anger-eliciting messages [19]. In the political context, one's anger positively predicts his or her information-sharing behavior through the interpersonal communication [32]. Similarly, anger causally increases people's sharing of fake news on social media [33]. As such, we predict a positive relationship between anger and information-sharing behavior amid the pandemic (H2b).

Prior research found that sadness motivates people's desire for social connectedness and enhances their engagement in social behaviors [34]. Therefore, we expect sadness to be positively linked with information-sharing behavior, which can function as means of social interaction amid the pandemic (H2c). Formally:

H2a: anxiety is positively associated with information-sharing behavior.

H2b: anger is positively associated with information-sharing behavior.

H2c: sadness is positively associated with information-sharing behavior.

2.4 Emotions and preventive health behaviors

Preventive health behavior refers to “any activity undertaken by a person believing himself to be healthy, for the purpose of preventing disease or detecting it in an asymptomatic state” [35]. At the pandemic outbreak, Chinese people actively followed the recommended preventive measures, contributing to China's effective containment of the pandemic [36]. Since anxious people perceive greater risks and higher uncertainty of the environment [25, 37], it is expected that anxious people would perceive greater risks associated with the coronavirus disease and consequently exhibit greater engagement with preventive health behaviors (H3). There are no specific predictions for the associations between anger and sadness and preventive health behaviors. Formally:

H3: anxiety is positively associated with the adoption of preventive health behaviors.

2.5 Emotions and stockpiling behavior

People stockpile resources when facing crises [38]. The stockpiling behavior may be driven by instinctive self-protection motivation or mediated by an emotional channel [8]. Stockpiling under crises was described as “taking back control in a world where you feel out of control” [38], suggesting that desire for control is the underlying driving force. Hence, anxiety may drive stockpiling behavior [39], as means of gaining control. Thus, a positive anxiety–stockpiling association is predicted such that the more anxious one is, the stronger one's intention to stockpile preventive goods amid the pandemic (H4a).

Additionally, stockpiling behavior as a selfish hoarding of resources for oneself is affected by people's tendency to adopt other-focused perspectives. Interestingly, anger and sadness exert opposing impacts on this dimension, with anger lowering other-focused orientation [18] whereas sadness enhancing other-focused orientation [22]. Angry people have a lower willingness to engage in other-focused actions due to the “holding others accountable” appraisal theme [18]. Hence, we predict that angry people would exhibit a stronger intention to stockpile goods (H4b). In contrast, people who experience sadness have more other-oriented considerations and are more willing to take other individuals' needs into consideration. Therefore, sadness may reduce people's intention to stockpile preventive goods for themselves so that others in need would get access to the resources (H4c). Formally,

H4a: anxiety is positively associated with stockpiling behavior.

H4b: anger is positively associated with stockpiling behavior.

H4c: sadness is negatively associated with stockpiling behavior.

2.6 Methodology

2.6.1 Survey and participants

An online survey was distributed via social media platforms (e.g., WeChat and Baidu Post Bar) among mainland Chinese residents from February 2, 2020 to February 9, 2020 during the early outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Only adult participants (18 years and above) who completed an electronic consent form were allowed to participate. Given the high uncertainty of the development of the Covid-19 pandemic, the data collection duration was set as 1 week and aimed to recruit as many participants as possible to obtain a representative sample. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Medical College, University of South China.

2.6.2 Measurements

A screening question was set first to exclude the participants under the age of 18 and those who did not agree to participate in the survey. Then we measured in the following order: participants' information-seeking and information-sharing behaviors, adoption of preventive health behaviors, intention to stockpile personal preventive equipment, and their emotional reactions. Finally, after providing socio-demographic information, participants entered a lucky draw to receive a monetary incentive of 6 CNY (equivalent to 0.86 USD).

Information-seeking behavior and information-sharing behavior

Participants were instructed to report how frequently they searched Covid-19-related information recently from different sources, including Weibo, WeChat, conversations in WeChat groups, QQ, news apps, online forums, blogs, TV, radio, newspapers, magazines, and Twitter (12 items, α = 0.86). All questions were administered along 5-point scales (1 = never to 5 = very frequently).

Participants' information-sharing behaviors were assessed with a multiple-answer question that instructed them to indicate whether they had recently forwarded, commented, and posted on six popular social media platforms (Weibo, WeChat, QQ Zoon, news apps, online forums, and foreign media like Twitter; six items, one for each channel). Each behavior (forward, comment, and post) was coded as 1 (=yes) or 0 (=no). If participants did none of the above sharing behaviors on a given channel, they were instructed to choose the option “none” (0 = none, 1 = forwarded, 1 = commented, 1 = posted on the platform).

Engagement with World Health Organization-recommended preventive health behaviors

We assessed participants' engagement with precaution behaviors as recommended by World Health Organization (WHO) for healthy people to protect themselves from contracting the coronavirus disease [36]. Specifically, participants reported their frequency of the following behaviors: “wearing masks,” “washing hands,” “sanitizing clothes or other items,” “sneezing into their elbows,” and “staying at home in self-quarantine” on 5-point scales (1 = never, 5 = very frequently).

Decision to stockpile personal preventive goods

We measured participants' decision to purchase personal preventive products by instructing them to indicate how many face masks they would like to buy were there 20 pieces left in stock along a 5-point scale (1= “0 pieces,” 2 = “1–5 pieces,” 3 = “6–10 pieces,” 4 = “11–15 pieces,” and 5 = “16–20 pieces”). A larger quantity of masks a participant reported purchasing indicated his/her higher willingness to stockpile.

Affective reactions toward the pandemic

Participants reported their emotional sadness, anger, and anxiety (three items: anxious, desperate, and worried, α = 0.83) in responding to Covid-19 (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely).

Demographics

Finally, participants provided basic socio-demographic information, including age (years old), gender (0 = female, 1 = male), highest obtained education (1 = high school or below, 2 = professional school, 3 = bachelor's degree, 4 = graduate degree or above), annual household income (1 = 70,000 or less, 2 = 70,001–100,000, 3 = 100,001–150,000, 4 = 150,001–300,000, 5 = more than 300,000; CNY), marital status (0 = single, 1 = in relationship or married), and residence (the current living province).

3 RESULTS

A response rate of 54.73% was obtained. Invalid questionnaires (incomplete data, duration shorter than 5 min, and duration outlier data) were excluded, eventually leaving 2796 participants in the following analyses.

3.1 Sample statistics

Among the 2796 participants (age 18–85, Mage = 30.46, SD = 8.59), 49.2% were female (n = 1376), 53.6% were married (n = 1498), 47.2% had an annual household income of 100,000–150,000 CNY and more (n = 1321), 49.2% had a college degree or above (n = 1376), and 59.5% lived in the city (n = 1663).

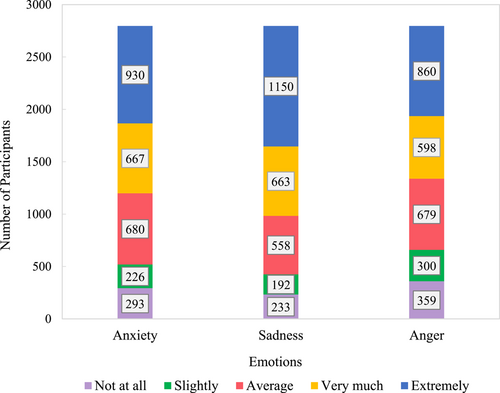

3.2 Emotional reactions

Descriptive analyses on participants' emotions showed that participants' experienced anxiety (M = 3.36, SD = 1.15), sadness (M = 3.83, SD = 1.27), and anger (M = 3.47, SD = 1.36) were significantly higher than the scale midpoint (=3, t > 16.14, p < 0.001). Specifically, 81.4% of the participants (n = 2277) reported intense anxiety (≥3), 76.4% of the participants (n = 2137) reported strong anger (≥3), and 84.8% of the participants (n= 2371) reported intense sadness (≥3). These results suggested that most of the surveyed participants experienced strong negative emotions during the early outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic (see Figure 2).

Then, each assessed pandemic-related behavior was sent to a regression analysis with these three emotions as predictors to test our hypotheses. Results for each behavior were reported below respectively (see Table 1 for results summary and Table 2 for whether each hypothesis was supported or not). Note that the same conclusions were obtained with demographic variables included in the regression models.

| Information-seeking behavior | Information-sharing behavior | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% CI | t-test | p Value | B | SE | 95% CI | t-test | p Value | |

| Anxiety | 0.08 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.11] | 3.97 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.10 | [0.68, 1.07] | 8.77 | <0.001 |

| Sadness | −0.07 | 0.02 | [−0.10, −0.03] | −3.93 | <0.001 | −0.57 | 0.09 | [−0.74, −0.40] | −6.60 | <0.001 |

| Anger | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.34 | 0.73 | 0.18 | 0.08 | [0.03, 0.34] | 2.31 | 0.02 |

| Adoption of preventive health behaviors | Stockpiling of personal preventive goods | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% CI | t-test | p Value | B | SE | 95% CI | t-test | p Value | |

| Anxiety | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.10, −0.02] | −2.93 | 0.003 | 0.13 | 0.03 | [0.07, 0.19] | 4.19 | <0.001 |

| Sadness | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 1.26 | 0.21 | −0.09 | 0.03 | [−0.15, −0.04] | −3.37 | 0.001 |

| Anger | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] | −0.37 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 0.03 | [−0.001, 0.10] | 1.92 | 0.055 |

| Hypotheses | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| H1a | Anxiety is positively associated with information-seeking frequency. | Supported |

| H1b | Sadness is negatively associated with information-seeking frequency. | Supported |

| H2a | Anxiety is positively associated with information-sharing behavior. | Supported |

| H2b | Anger is positively associated with information-sharing behavior. | Supported |

| H2c | Sadness is positively associated with information-sharing behavior. | Rejected |

| H3 | Anxiety is positively associated with preventive health behaviors. | Rejected |

| H4a | Anxiety is positively associated with stockpiling behavior. | Supported |

| H4b | Anger is positively associated with stockpiling behavior. | Supported |

| H4c | Sadness is negatively associated with stockpiling behavior. | Supported |

3.3 Emotions and information-seeking behavior (H1a, 1b)

Participants’ information-seeking behavior was calculated by averaging their self-reported frequency of acquiring information via the assessed sources (α = 0.86). Regressing this index with anxiety, sadness, and anger as predictors, we found that participants searched information more frequently when they experienced stronger feelings of anxiety (B = 0.08, SE = 0.02, t = 3.97, p < 0.001, 95% CI: [0.04, 0.11]), but less frequently so when they experienced stronger sadness (B = −0.07, SE = 0.02, t = −3.93, p < 0.001, 95% CI: [−0.10, −0.03]). Emotional anger (p = 0.73) had no effect on participants’ information-seeking behavior. H1a and H1b were supported.

3.4 Emotions and information-sharing behavior (H2a–2c)

Information-sharing behavior was calculated by summing up participants’ reported activities of sharing, commenting, and posting articles on the six social media platforms. The regression results revealed that participants’ information-sharing behavior was positively associated with anxiety (Β = 0.87, SE = 0.10, t = 8.77, p < 0.001, 95% CI: [0.68, 1.07]) and anger (Β = 0.18, SE = 0.08, t = 2.31, p = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.03, 0.34]), but was negatively associated with sadness (Β = −0.57, SE = 0.09, t = −6.60, p < 0.001, 95% CI: [−0.74, −0.40]). These results supported H2a and H2b, but contradicted H2c.

3.5 Emotions and preventive health behaviors (H3)

Participants’ engagement with WHO-recommended preventive health behaviors was computed by averaging their reported frequency of taking each recommended behavior (α = 0.65; M = 3.92, SD = 0.81). The regression results showed that anxiety (B = −0.06, SE = 0.02, t = −2.93, p = 0.003, 95% CI: [−0.10, −0.02]) was negatively associated with preventive health behavior, contradicting H3. Sadness (p = 0.21) and anger (p = 0.71) had no effects.

3.6 Emotions and stockpiling behavior (H4a–4c)

The regression results revealed a positive association between anxiety and quantity, such that more anxious people would purchase more face masks (B = 0.13, SE = 0.03, t = 4.19, p < 0.001, 95% CI: [0.07, 0.19]). Anger had a directionally significant (p = 0.055) positive relationship with stockpiling. There was a negative association between sadness and quantity: sadder participants would purchase fewer face masks (B = −0.09, SE = 0.03, t = −3.37, p = 0.001, 95% CI: [−0.15, −0.04]), supporting H4a, H4b, and H4c.

4 DISCUSSION

In this research, Chinese participants’ negative emotional experiences were explored during the pandemic, and the associations between discrete negative emotions (anxiety, anger, and sadness) and behavioral reactions (information seeking, information sharing, preventive health behaviors, and stockpiling of personal preventive goods) toward the pandemic were investigated. Supporting most of the hypotheses, the results revealed differential effects of discrete negative emotions on people's various pandemic-related behaviors.

4.1 Principal results

As shown in Table 2, we found that more anxious people more frequently sought (H1a) and shared (H2a) pandemic-related information. The positive effects of anxiety on information-seeking and information-sharing behaviors are consistent with prior research findings that anxious people are motivated to seek control [25]. To elaborate, during the early outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the uncertainty underlying Chinese participants’ anxiety was due to their lack of knowledge about the novel coronavirus disease. Actively seeking and sharing information can provide people with the information needed for proper evaluation and assessment of the situation, alleviating their uncertainty and hence reducing their anxiety. Moreover, we found that angrier people more frequently shared information (H2b), corroborating prior research finding that anger-inducing messages increase people's intention to repost [29]. Again, supporting our prediction, sadness was found to be negatively associated with information-seeking behavior (H1b). This supports our theorizing. During the early outbreak, pandemic-related information was mainly about the growing number of confirmed cases and reported deaths, which would make people feel sad. Hence, sad people would be less willing to seek information to avoid exposure to the sadness-eliciting cues [28].

However, contrasting our hypothesized positive link between sadness and information sharing (H2c), we found a negative association. One possible explanation for the observed negative association might be the content of shared information. Specifically, the information shared by participants during the survey distribution was most likely negatively valenced and may elicit sadness; hence, participants who experienced intense sadness tended to avoid sharing such information to regulate their sad feelings. Unfortunately, we did not assess the content of the information shared by the participants, leaving this explanation untested.

Opposing H3, we found a negative relationship between anxiety and preventive health behaviors, such that the more anxious people felt, the lower their intention to adopt preventive measures. We speculate that one possible explanation might be participants’ high intensity of anxious feelings toward the pandemic. Prior research showed that people's adoption of precautionary measures amid the 2003 SARS-CoV epidemic was positively associated with lower levels of anxiety [40], implying that too intense anxiety might inhibit the adoption of precautionary measures. The observed negative anxiety-preventive health behaviors association highlights the maladaptive consequences of intense anxiety induced by the pandemic and urges health organizations to provide people with effective strategies for regulating and coping with anxiety [41].

Lastly, people's stockpiling behavior was affected by anxiety, anger, and sadness in patterns consistent with H4a–4c. In alignment with prior research, anxiety motivates hoarding of resources for self-protection [31, 42]. Sadness (vs. anger) reduces (vs. enhances) stockpiling due to the underlying appraisals of blame attribution [43]. Sad participants who attribute the adversity to situational factors are more inclined to consider others’ needs and thus exhibit lower intention to selfishly hoard goods. In contrast, angry participants who hold others accountable for the adversity have few other-oriented considerations and thus are more likely to stockpile preventive goods.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This research is among the first to differentiate the effects of three commonly experienced negative emotions (anxiety, anger, and sadness) amid public health crises on the key behavioral reactions toward the Covid-19 pandemic through the lens of the appraisal theory of emotion. The findings enrich extant understanding of the distinct emotion–behavior relationships amid the Covid-19 pandemic, and add to the literature on emotions and coping behaviors amid crises.

From a practical standpoint, it is critical for authorities to disseminate information, implement interventions, incent changes in policies, and promote the public's extensive engagement. The findings generate insights for encouraging people's adoption of pandemic-coping measures. Foremost, since anxiety, anger, and sadness have unique relationships with different pandemic-related behaviors, authorities should properly assess people's emotional states and correspondingly provide effective preventive measure suggestions. Moreover, prevention intervention programs may induce specific emotions via message framing to enhance people's adoption of the coping behavior [44]. For example, as sadness was found to reduce stockpiling behavior, authorities may consider eliciting sad emotion in messages that persuade people to avoid excessive purchases.

5.1 Limitations and future research

One limitation of this research is that we examined only Chinese people, which, to some extent, renders the conclusions subject to cultural differences. The different development stages of the pandemic and variations in the progress of combatting the pandemic in different regions may influence people's emotional experiences and subsequently their behavioral reactions. However, considering the universality of the appraisal antecedents of anxiety, anger, and sadness, we expect that the revealed emotion–behavior relationships would remain consistent across cultures [45]. Future research may examine the emotion–behavior relationships among people with different cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, we only examined anxiety, sadness, and anger, leaving other pandemic-elicited negative emotions (e.g., fear, loneliness, and helplessness) untested. Future research may study these emotions and their influences on people's pandemic-coping behaviors. Besides, future research can analyze social media posts. To explore how the contents of shared information influence people's emotions and behaviors.

Moreover, a convenient sampling approach was adopted. To examine participants’ information-seeking and information-sharing behaviors on social media platforms, only participants who had access to the Internet were recruited and assessed, which undermines the generalizability of the conclusions to the whole Chinese population. Considering the urgency of the Covid-19 pandemic and the common risks faced by every citizen, the findings still provide important implications for designing intervention programs. Future studies can adopt a probability-based sampling method if the health issue is not an emergency. Stockpiling behavior was measured with a hypothetical scenario. Future research may adopt secondary transaction data of preventive goods as well as daily necessity products to validate the findings.

Finally, this research focused on the downstream consequences of emotional experiences, leaving the antecedents of people's emotional reactions toward the pandemic untapped. Future research may investigate the situational factors amid the Covid-19 pandemic that elicit each individual negative emotion to provide a comprehensive picture of the public's emotional reactions and corresponding behavioral reactions amid the pandemic.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tingting Wang: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); project administration (lead); supervision (lead); validation (lead); visualization (lead); writing − original draft (lead); writing − review & editing (lead). Xin Zheng: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing − original draft (equal); writing − review & editing (equal). Zhaomeng Niu: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing − original draft (equal); writing − review & editing (equal). Pengwei Hu: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing − original draft (equal); writing − review & editing (equal). Ruiqi Dong: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing − original draft (equal); writing − review & editing (equal). Zhihan Tang: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing − original draft (equal); writing − review & editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71802198), University of South China Covid-19 epidemic prevention and control scientific research emergency project (2020-2-5), Hunan province 2020 innovative province construction special topic to combat Covid-19 epidemic emergency (2020SK3010), and Major Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 21ZDA036).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the survey.

INFORMED CONSENT

None.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data and material are available upon request.