HMGB1 blood levels and neurological outcomes after traumatic brain injury: Insights from an exploratory study

Abstract

Objective

Posttraumatic epilepsy (PTE) and cognitive impairment are severe complications following traumatic brain injury (TBI). Neuroinflammation likely contributes, but the role of specific inflammatory mediators requires clarification. High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is an inflammatory cytokine released after brain injury that may be involved. This prospective longitudinal study investigated whether serum HMGB1 levels are associated with PTE development and cognitive decline over 12 months post-TBI.

Methods

Serum samples were collected from 41 TBI patients, including mild and moderate to severe, at baseline, 6, and 12 months following TBI. HMGB1 was quantified by ELISA alongside interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Cognitive assessments using validated neuropsychological assessments were performed at 6 and 12 months. The occurrence of PTE was also tracked.

Results

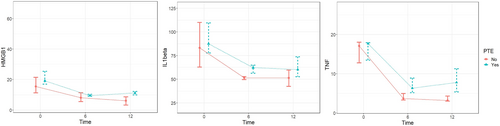

HMGB1 remained elevated at 12 months post-TBI only in the subgroup (n = 6) that developed PTE (p = 0.026). PTE was associated with moderate to severe TBI cases. Higher HMGB1 levels at 12 months correlated with a greater decline in Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination scores (p < 0.05). Reductions in HMGB1 (p < 0.05), IL-1β (p < 0.05) and TNF (p < 0.001) levels from 6 to 12 months correlated with improvements in cognitive scores. Multivariate regression analysis confirmed that HMGB1 level changes were independently associated with cognitive trajectory post-TBI (p = 0.003).

Significance

The study highlights the importance of understanding the interactions between HMGB1 and inflammatory markers in posttraumatic neuroinflammatory responses. Targeting HMGB1 and associated markers may offer a promising strategy for managing chronic neuroinflammation and mitigating cognitive deficits in TBI patients, emphasizing the potential for targeted therapeutic interventions in this context.

Plain Language Summary

This study examines how a protein called HMGB1 may contribute to epilepsy and cognitive deficits after traumatic brain injury (TBI). Patients with higher HMGB1 levels were more likely to develop epilepsy and experience significant cognitive decline within a year. Reducing HMGB1 and related inflammation was associated with better cognitive function and overall brain health. These findings suggest that HMGB1 could be a valuable marker and a potential target for treatments to prevent epilepsy and improve brain recovery after TBI.

Key points

- Persistent elevation of HMGB1 post-TBI links to PTE development.

- Higher HMGB1 at 12 months post-TBI predicts greater cognitive decline.

- Reductions in HMGB1, IL-1β, and TNF from 6 to 12 months correlate with cognitive improvement.

- HMGB1 changes independently predict cognitive trajectory after TBI, irrespective of other factors.

1 INTRODUCTION

Posttraumatic epilepsy (PTE) and cognitive impairment are serious complications that can arise after traumatic brain injury (TBI), diminishing quality of life. Up to 20% of patients develop PTE within ten years following TBI, while over 50% experience persistent cognitive deficits.1 Results from a systematic review revealed that PTE is associated with cognitive impairment up to 35 years following TBI.2 The pathophysiology underlying the development of these chronic neurological disorders remains poorly elucidated. However, emerging evidence suggests that neuroinflammation likely plays a pivotal role.3

In particular, the inflammatory mediator high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) has recently garnered much interest regarding its implications in epileptogenesis and neurodegeneration. HMGB1 is typically expressed in cell nuclei but can be passively released by necrotic cells or actively secreted by inflammatory cells in response to injury.4 HMGB1 can also be released from peripheral tissues as part of a systemic inflammatory response to injury, which underscores its broader role in inflammatory processes.4 Once released, extracellular HMGB1 behaves as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), triggering further inflammatory signaling through receptors like toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and receptors for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) expressed on neurons and glia.5

HMGB1 is overexpressed in resected brain tissue and elevated systemically in patients with epilepsy compared to controls in several cross-sectional studies.6, 7 Higher levels also correlate with poorer seizure control and anti-epileptic drug resistance.8 Similarly, increased cerebral and circulating HMGB1 levels are associated with cognitive dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease.9 These findings suggest HMGB1 likely contributes to epileptogenesis and cognitive decline.

This study focuses on HMGB1's role in a systemic inflammatory response following TBI, exploring whether elevated HMGB1 levels over time correlate with the risk of PTE and cognitive decline. No longitudinal studies have yet examined HMGB1 profiles following TBI in relation to the eventual emergence of PTE and cognitive comorbidities. Most existing clinical data on inflammatory molecules in PTE derive from cross-sectional analyses with limited insight into temporal dynamics.10-12 Consequently, the functional implications of post-TBI alterations in cytokines like HMGB1 for long-term neurological outcomes remain unclear.

- Serum HMGB1 levels will remain persistently elevated over 12 months post-TBI in patients who ultimately develop PTE compared to those who remain seizure-free.

- Prolonged HMGB1 elevation correlates with and predicts greater cognitive decline.

Clarifying the role of HMGB1 as a mediator of acute neuroinflammation driving chronic post-TBI complications can uncover novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for improving neurological outcomes. This study offers crucial longitudinal human data to elucidate these mechanisms.

2 METHOD

2.1 Study setting and study population

This longitudinal study was conducted at Hospital Canselor Tuanku Muhriz (HCTM), Kuala Lumpur. All TBI patients admitted to the Neurosurgical Ward who meet the inclusion criteria were recruited: (a) above 18 years old, (b) patient or guardian able to understand and speak English/Malay/Chinese, (c) admitted for TBI cause in 72 h. We excluded patients with the following criteria: (a) have pre-existing epilepsy before TBI, (b) contraindicated for neuroimaging or EEG, (c) have neurological disorders before TBI, e.g., brain tumor, stroke, meningitis, and dementia, (d) subjects or families unwilling or unable to comply with scheduled visits, laboratory tests, and other study procedures.

The recruitment period was from January 2021 to June 2022. Informed consent was gained from the patient and/or the patient's caregiver or family members before recruitment.

2.2 Sample

From January 2021 to June 2022, we recruited 60 TBI patients meeting inclusion criteria at HCTM, intending to reach half of the pre-pandemic annual TBI cases (N = 120, based on 2019 data). Nineteen participants dropped out during the study, comprising four individuals who passed away, four who relocated, eight who declined follow-up appointments and three who were uncontactable. The final cohort comprised 41 participants. No significant differences were observed in age (p = 0.188), education (p = 0.486), and injury severity (p = 0.817) between the patients included in the analysis and those who were lost to follow-up.

2.3 Study variables

- Demographic variables and injury characteristics that have the potential to independently influence brain recovery trajectories.: Age, gender, ethnicity, alcohol intake, year of education, previous history of head injury, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) during admission, presence of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), intake of antiseizure medication (ASM), depression score.

- HMBG1, IL-1β, and TNF measurements: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the most commonly used method for HMGB1 detection in serum, was used.13 Blood samples were collected at the acute phase (within 72 h of admission), followed by six and 12-month follow-ups.

-

Cognitive assessment: Cognitive evaluations were performed two times, at six months and 12 months post-TBI, using:

- Presence of PTE: PTE was defined as seizures occurring after TBI, with onset observed beyond the acute post-injury phase. Early seizures (within one-week post-injury) were monitored but were not included in the diagnostic criteria for PTE. The seizure was captured by nurses and doctors during admission and by the patient's caregiver at home from the day of discharge until 12 months post-TBI. The hospital neurologist made an epilepsy diagnosis through clinical evaluation and EEG monitoring as an adjunct.

The five cognitive domains assessed by the ACE-III exams include language, verbal fluency, attention, memory, and visuospatial ability. Scores on each individual subtest were produced, along with a composite total score of up to 100.21 CTMT (Trail 1–5) is one of the most extensively used neuropsychological assessments in brain injury patients, evaluating frontal lobe abnormalities, attention, set-shifting impairments, and numerous other cognitive issues through visual search and sequencing tasks.18, 22 Symbol search and coding subtests from the WAIS-IV were used to evaluate a person's speed and efficiency in processing simple or routine visual information (processing speed).22, 23 All tests were performed by a clinical neuropsychologist and a trained researcher under the supervision of the clinical neuropsychologist.

2.4 Serum analysis

All patient samples were processed following the principles of Good Clinical Practice. Patients with TBI provided peripheral venous blood samples of two milliliters within seventy-two hours of admission. After that, the blood samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 1200 × g to extract the serum, which had been left to stand at room temperature for 30 min. Following that, the gathered serum samples were refrigerated at −80°C. The serum levels of HMGB1, IL-1β, and TNF were quantified by utilizing commercially accessible enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Elabscience Biotechnology Inc). The assays were carried out per the manufacturer's guidelines. Each blood sample was examined in an identical laboratory. The results for HMGB1 were expressed as ng/mL and pg/mL for IL-1β and TNF. The absorbance of samples was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instrument/USA). ELISA measurements for each patient were performed in duplicate on the same day according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 29.0 (SPSS Chicago, IL, USA). OriginPro 2023b (OriginLab Corporation) was used for visualizing data trends. Normality tests were done, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare inflammatory biomarkers HMGB1, IL-1β, and TNF levels at various time points (0, 6, and 12 months) between PTE and non-PTE groups. Specifically, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess changes within groups over time – comparing biomarker levels at 0 versus 6 months, 0 versus 12 months, and 6 versus 12 months for the PTE and non-PTE groups separately. The paired Mann–Whitney U test was applied for between-group comparisons of biomarker levels at each matched time point. These analyses evaluated longitudinal dynamics. The correlation between changes in HMGB1 levels and cognitive score was analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation. Linear regression modeling was used to identify the association between changes in HMGB1 levels and PTE status with changes in cognitive performance post-TBI after adjusting for confounders. All statistical tests were interpreted at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of the study population

We included 41 TBI patients who completed the 6-month and 1-year follow-up (Table 1). The median follow-up time was 12.3 months. The majority were young (82.9%) with a median age of 32 (IQR: 28) years and predominantly male (92.7%). The leading cause of TBI was road traffic accidents (82.9%), with 15 patients (36.6%) categorized as mild, 10 patients (24.4%) as moderate, and 16 patients (39%) as severe TBI. More than three-quarters (75.6%) had 0 to 1 comorbidity, while alcohol consumption was infrequent (17.1%).

| Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | Young (up to 59) | 34 | 82.9 |

| Old (≥60) | 7 | 17.1 | |

| Gender | Male | 38 | 92.7 |

| Female | 3 | 7.3 | |

| Ethnicity | Malay | 19 | 46.3 |

| Chinese | 13 | 31.7 | |

| Indian | 9 | 22.0 | |

| Alcohol consumption | Ever | 7 | 17.1 |

| Never | 34 | 82.9 | |

| Prior history of head injury | Yes | 4 | 9.8 |

| No | 37 | 90.2 | |

| Number of comorbidities | 0–1 | 31 | 75.6 |

| ≥2 | 10 | 24.4 | |

| Etiology of TBI | RTA | 34 | 82.9 |

| Fall | 6 | 14.6 | |

| Assault | 1 | 2.4 | |

| TBI severity | Mild | 15 | 36.6 |

| Moderate to severe | 26 | 63.4 | |

| Posttraumatic epilepsy | Yes | 6 | 14.6 |

| No | 35 | 85.4 | |

Out of the 41 TBI patients, six patients developed PTE (14.63%), all within six months post-TBI, with median days to develop PTE being 45 (IQR: 37) days. All six PTE patients had moderate to severe TBI, with no mild TBI cases developing PTE. Regarding comorbidities, only one PTE patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, while the remaining five had no comorbidities. In contrast, 13 of the 35 non-PTE patients had comorbidities, with conditions including hypertension, ischemic heart disease, dyslipidemia, and morbid obesity.

Among the six patients who developed PTE, early seizures were observed in four patients. Characteristics of seizure onset were tabulated in Table 2.

| Patient | Time of seizure onset (days post-TBI) | Type of seizure | Early seizure observed | Antiseizure medications given at each blood draw |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 45 | Focal Seizure | Yes | Yes (0, 6, 12 months) |

| 02 | 30 | Generalized Tonic–Clonic | Yes | Yes (0, 6, 12 months) |

| 03 | 20 | Focal Seizure with Secondary Generalization | Yes | Yes (0, 6, 12 months) |

| 04 | 50 | Focal Seizure | No | No (0 months); Yes (6, 12 months) |

| 05 | 60 | Generalized Tonic–Clonic | No | Yes (0, 6, 12 months) |

| 06 | 35 | Focal Aware Seizure | Yes | Yes (0, 6, 12 months) |

3.2 Serum HMGB1, IL-1β and TNF quantification by ELISA

The mean and median concentrations of HMGB1, IL-1β, and TNF at 0, 6, and 12 months for the entire cohort (N = 41) consistently decreased over the year-long observation period. The mean levels of HMGB1 decreased notably from 18.5 ng/mL at 0 months to 8.41 ng/mL at 12 months. Similarly, the mean levels of IL-1β and TNF decreased over one-year post-TBI (Table 3).

| Biomarker and time (month) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| HMGB1 at 0 | 18.5 (10.7) | 16.6 (10.5) |

| HMGB1 at 6 | 9.00 (5.01) | 8.82 (4.96) |

| HMGB1 at 12 | 8.41 (6.54) | 6.62 (7.21) |

| IL-1β at 0 | 83.7 (30.4) | 83.2 (44.6) |

| IL-1β at 6 | 52.7 (8.43) | 51.8 (5.47) |

| IL-1β at 12 | 50.6 (16.8) | 51.7 (15.4) |

| TNF-α at 0 | 15.7 (5.63) | 17.5 (5.90) |

| TNF-α at 6 | 4.62 (1.97) | 4.03 (1.84) |

| TNF-α at 12 | 4.60 (3.39) | 3.20 (1.64) |

- Abbreviations: HMGB1, High Mobility Group Box 1; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 beta; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor.

The Friedman test confirmed a significant overall difference in HMGB1 levels across the three time points (p < 0.001). Wilcoxon signed-rank tests revealed significant reductions in HMGB1 levels from baseline (0 months) to both six months (p < 0.001) and 12 months (p < 0.001).

3.2.1 IL-1β levels over time

Similar patterns were observed for IL-1β levels. The Friedman test underscored a significant overall difference in IL-1β levels across the three time points (p < 0.001). Wilcoxon signed-rank tests indicated significant reductions from baseline (0 months) to both six months (p < 0.001) and 12 months (p < 0.001). No significant difference was found between IL-1β levels at 6 and 12 months (p = 0.507).

3.2.2 TNF levels over time

For TNF levels, the Friedman test showed a significant overall difference in TNF levels across the three time points (p < 0.001). Wilcoxon signed-rank tests demonstrated significant reductions from baseline (0 months) to both six months (p < 0.001) and 12 months (p < 0.001). Similarly, no significant difference was observed between TNF levels at 6 and 12 months (p = 0.210).

HMGB1, IL1-β and TNF levels and PTE development

Detailed stratifications by TBI severity, seizure onset, CNS pathology and medication use are presented in Tables 4 and 5 to contextualize their relationship with inflammatory markers levels. Mann–Whitney U tests revealed significant differences in TNF levels between mild and moderate/severe TBI groups at 6 and 12 months (p = 0.012 and p = 0.024, respectively), supporting the association between TBI severity and sustained inflammation. Moderate/severe TBI group particularly those with specific CNS pathologies like hemorrhage and brain edema, are more prone to sustained inflammation, as reflected by TNF levels. This inflammatory state may set the stage for PTE development, highlighting the importance of TBI severity and CNS pathology in post-TBI outcomes. No statistically significant impact of antiseizure, sedative, or anti-inflammatory medication use on HMGB1, IL-1β, or TNF levels in this cohort at any time point of the study.

| Underlying conditions | N | HMGB1 at 0 | HMGB1 at 6 | HMGB1 at 12 | IL-1β at 0 | IL-1β at 6 | IL-1β at 12 | TNF at 0 | TNF at 6 | TNF at 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI severity | ||||||||||

| Mild | 14 | 21.5 (11.6) | 9.68 (11.2) | 7.4 (9.73) | 89.1 (33.4) | 51.3 (2.38) | 51.5 (25) | 17.1 (3.72) | 3.39 (0.77) | 3.14 (1.1) |

| Moderate/severe | 27 | 15.8 (6.88) | 8.06 (3.81) | 6.23 (6.48) | 78.4 (48.1) | 51.8 (10.1) | 54.1 (15.1) | 17.6 (5.94) | 4.95 (1.61) | 4.21 (2.45) |

| p-value | 0.151 | 0.111 | 0.111 | 0.66 | 0.483 | 0.471 | 0.847 | 0.012* | 0.024* | |

| Early seizure | ||||||||||

| Yes | 12 | 16.2 (7.17) | 8.82 (4.59) | 6.99 (6.03) | 80.3 (43.8) | 53.9 (10.7) | 50.9 (18.6) | 17.9 (2.69) | 4.4 (0.99) | 4.12 (1.51) |

| No | 29 | 16.6 (13.4) | 8.69 (4.59) | 6.61 (6.03) | 83.2 (43.8) | 51.6 (3.4) | 53.1 (12.1) | 17 (5.75) | 3.66 (1.89) | 3.19 (1.82) |

| p-value | 0.788 | 0.474 | 0.678 | 0.83 | 0.118 | 0.581 | 0.144 | 0.077 | 0.246 | |

| CNS pathology | ||||||||||

| Hemorrhage | 35 | 16.6 (10.2) | 8.82 (3.86) | 6.62 (6.64) | 78.4 (48.1) | 51.8 (7.36) | 53.1 (14.2) | 17.1 (5.14) | 4.21 (1.78) | 3.19 (2.01) |

| No hemorrhage | 6 | 15 (10.2) | 11.8 (13.4) | 7.91 (11.9) | 92.2 (25.5) | 50.4 (2.29) | 50.7 (22.9) | 17.8 (8.52) | 3.3 (0.14) | 3.85 (1.28) |

| p-value | 0.872 | 0.58 | 0.927 | 0.698 | 0.09 | 0.602 | 0.825 | 0.046* | 0.897 | |

| Contusion | 9 | 15.5 (15.8) | 8.06 (7.49) | 4.19 (8.25) | 66.7 (71) | 51.2 (4.47) | 48.3 (44.8) | 16.8 (10.5) | 4.95 (1.3) | 3.19 (1.42) |

| No contusion | 32 | 16.6 (9.18) | 8.9 (4.21) | 6.75 (5.44) | 83.2 (31.1) | 51.8 (5.23) | 53.6 (10.4) | 17.5 (4.97) | 3.66 (1.81) | 3.25 (1.74) |

| p-value | 0.722 | 0.682 | 0.44 | 0.459 | 0.765 | 0.23 | 0.257 | 0.114 | 0.838 | |

| Brain edema | 12 | 17 (15.5) | 9.25 (2.87) | 6.62 (6.45) | 87.9 (48.6) | 50.8 (11.1) | 53.8 (14) | 17.4 (2.29) | 4.58 (2.05) | 4.76 (3.47) |

| No brain edema | 29 | 16.6 (10.8) | 8.06 (2.87) | 6.88 (6.45) | 83.2 (48.6) | 51.8 (11.1) | 51.7 (14) | 17.5 (2.29) | 3.66 (2.05) | 3.19 (3.47) |

| p-value | 0.328 | 0.647 | 0.576 | 0.509 | 0.943 | 0.877 | 0.709 | 0.108 | 0.034* | |

| Skull fracture | 33 | 16.6 (8.36) | 8.82 (6.66) | 6.88 (7.91) | 83.2 (41.3) | 51.6 (5.99) | 54.1 (19.3) | 17.5 (5.75) | 4.21 (1.84) | 3.81 (2.18) |

| No skull fracture | 8 | 20.1 (17) | 8.13 (2.98) | 6.19 (1.99) | 76.9 (41.1) | 52.5 (2.61) | 51.1 (6.38) | 17.5 (1.6) | 3.84 (1.01) | 3.18 (0.38) |

| p-value | 0.55 | 0.805 | 0.439 | 0.429 | 0.645 | 0.617 | 0.459 | 0.575 | 0.211 | |

| Posttraumatic epilepsy | ||||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 19.2 (8.39) | 9.47 (1.32) | 11.2 (2.27) | 87.5 (31.8) | 62.2 (8.52) | 60.3 (21.1) | 17.7 (4.43) | 6.32 (3.76) | 7.78 (5.92) |

| No | 35 | 15.5 (10.3) | 8.06 (5.81) | 6.14 (5.42) | 83.2 (47.3) | 51.6 (3.30) | 51.4 (17.1) | 17.1 (5.26) | 3.66 (1.65) | 3.19 (1.32) |

| p-value | 0.119 | 0.347 | 0.026* | 0.592 | 0.023* | 0.073 | 0.685 | 0.003* | 0.004* | |

- Note: Biomarker levels at 0, 6, and 12 months by TBI severity, early seizure, PTE and CNS pathology with Mann–Whitney U test results. NA indicates unavailable data due to universal use, e.g., all patients receive analgesics.

- Abbreviations: HMGB1, high mobility group box 1; IL-1β, interleukin-1 beta; IQR, interquartile range; PTE, posttraumatic epilepsy; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

- * p = <0.05.

| Medication type | Group | HMGB1 | IL-1β | TNF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiseizure at 0 month | Yes (n = 16) | 15.9 (9.87) | 75.4 (46.2) | 17.6 (5.9) |

| No (n = 25) | 17.2 (10.8) | 85.3 (32.5) | 17.3 (2.75) | |

| p-value | 0.788 | 0.83 | 0.144 | |

| Antiseizure at 6 month | Yes (n = 6) | 9.47 (1.32) | 62.2 (8.52) | 6.32 (3.76) |

| No (n = 35) | 8.06 (5.81) | 51.6 (3.30) | 3.66 (1.65) | |

| p-value | 0.474 | 0.118 | 0.077 | |

| Antiseizure at 12 month | Yes (n = 6) | 11.2 (2.27) | 60.3 (21.1) | 7.78 (5.92) |

| No (n = 35) | 6.14 (5.42) | 51.4 (17.1) | 3.19 (1.32) | |

| p-value | 0.678 | 0.581 | 0.246 | |

| Sedative at 0 month | Yes (n = 26) | 15.6 (8.07) | 80.8 (51.6) | 17.7 (3.03) |

| No (n = 15) | 19.6 (11) | 85.2 (31.3) | 17.1 (6.85) | |

| p-value | 0.495 | 0.807 | 0.155 | |

| Analgesic at 0 month | Yes (n = 41) | 16.6 (10.5) | 83.2 (44.6) | 17.5 (5.9) |

| No (n = 0) | – | – | – | |

| p-value | NA | NA | NA | |

| Anti-inflammatory at 0 month | Yes (n = 16) | 16.7 (9.79) | 76.9 (1.87) | 17.7 (2.23) |

| No (n = 25) | 16.6 (9.23) | 89.7 (49.6) | 16.8 (5.75) | |

| p-value | 0.251 | 0.374 | 0.398 |

Comparing PTE and non-PTE groups using the Mann–Whitney U test, there is a statistically significant difference in HMGB1 levels at 12 months, IL-1β levels at 6 months and TNF levels at 6 and 12 months between the PTE and non-PTE group. The change in HMGB1 levels from 6 to 12 months was significantly different between PTE and non-PTE groups (p = 0.008). No significant differences in HMGB1 changes from 0 to 6 months and 0 to 12 months between groups. Figure 1 depicted HMGB1 and the changes in levels, as well as IL-1β and TNF levels between PTE and non-PTE groups over a year.

HMGB1, IL-1β, and TNF levels at different time points (0, 6, and 12 months) within the PTE group (n = 6) vs. non-PTE group (n = 35)

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate whether differences between levels at 2-time points differed significantly within the PTE and non-PTE groups (see Table S1). Within the PTE group, there were significant decreases in HMGB1 levels from baseline to 6 months (p = 0.028), 6 to 12 months (p = 0.028), and baseline to 12 months (p = 0.028). This indicates a continual reduction in systemic inflammation, as measured by HMGB1, over the first year in patients who develop posttraumatic epilepsy. No significant changes were observed in IL-1β or TNF within the PTE group. In contrast, the non-PTE group demonstrated significant decreases across all three biomarkers. HMGB1 decreased from baseline to 6 months (p < 0.001), 6 to 12 months (p = 0.013), and baseline to 12 months (p < 0.001). Significant reductions were also seen for IL-1β from baseline to 6 months (p < 0.001) and baseline to 12 months (p < 0.001). Likewise, TNF decreased from baseline to 6 months (p < 0.001) and baseline to 12 months (p < 0.001) in these patients without PTE.

The cognitive performance scores, specifically ACE-III, CTMT, and WAIS-4, revealed a significant difference between the PTE and non-PTE groups at 6 and 12 months (Table 6). Patients in the PTE group exhibited significantly lower cognitive scores compared to the non-PTE group at both time points (see Figure S1).

| Test | Cognitive score | PTE | Non-PTE | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE-III | Mean (SD) at 6 months | 39.2 (26.4) | 82.5 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) at 12 months | 44.2 (21.4) | 82.5 (11.5) | <0.001 | |

| Median (IQR) at 6 months | 31.5 (16.8) | 85 (14.5) | 0.003 | |

| Median (IQR) at 12 months | 36 (8.75) | 85 (13) | 0.001 | |

| CTMT | Mean (SD) at 6 months | 103 (26.7) | 158 (42) | 0.004 |

| Mean (SD) at 12 months | 115 (33.5) | 161 (42.6) | 0.016 | |

| Median (IQR) at 6 months | 90.5 (7.75) | 155 (66) | 0.003 | |

| Median (IQR) at 12 months | 105 (31.8) | 160 (55.5) | 0.017 | |

| WAIS-IV | Mean (SD) at 6 months | 66.8 (14.2) | 81.6 (11.6) | 0.008 |

| Mean (SD) at 12 months | 62.2 (13.5) | 82.9 (12.9) | 0.025 | |

| Median (IQR) at 6 months | 63.5 (10.3) | 84 (7.5) | <0.001 | |

| Median (IQR) at 12 months | 60 (11) | 81 (15) | 0.005 |

- Note: Mann–Whitney U test used for between-group comparisons of cognitive scores at each time point.

HMGB1, IL-1β and TNF levels correlation with cognitive impairment

Correlation analysis highlighted significant relationships between changes in HMGB1, IL-1β, and TNF levels and cognitive score alterations (see Table S2). The r-values provide a quantified measure of the strength and direction of the associations between biomarker level changes and cognitive score changes over the 6 months.24 HMGB1 level changes and ACE-III score difference exhibit a moderate negative correlation of r = −0.375 (p < 0.05) between changes in HMGB1 levels and cognitive score changes. Similarly seen in IL-1β level changes that show a moderate negative correlation with ACE-III score changes (r = −0.337, p < 0.05). TNF levels have a strong negative correlation with ACE-III (r = −0.541, p < 0.001) and WAIS-IV (r = −0.460, p < 0.05).

HMGB1 relationship with IL-1β and TNF

There is a moderately positive correlation between HMGB1 and IL-1β (r = 0.339, p < 0.05) and a moderately positive correlation between HMGB1 and TNF (r = 0.349, p < 0.05). The positive correlations indicate a general tendency for levels of HMGB1 to increase when levels of either IL1-β or TNF increase. So, higher inflammatory signaling via these cytokines seems associated with more HMGB1 release.

3.3 Association of cognitive function changes with changes in HMGB1 levels and PTE

We conducted linear regression models to examine the association between changes in cognitive function (from 6 to 12 months), measured using the ACE-III scale, and two predictors: differences in HMGB1 levels (from 6 to 12 months) and the presence of PTE (Table 7). The ACE-III test was chosen for its comprehensive measure of cognitive function and reliability within the TBI population.21, 25

| Univariate regression | Multivariate regression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

| Independent variables | B (SE B) | p-value | R 2 | 0.261 | 0.418 | 0.665 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.222 | 0.335 | 0.594 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.003 | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| F | 6.702 | 5.031 | 9.377 | ||||||

| B (SE B) | p-value | B (SE B) | p-value | B (SE B) | p-value | ||||

| Age | 0.060 (−0.064, 0.184) | 0.335 | |||||||

| Gender | 3.833 (−4.307, 11.973) | 0.347 | |||||||

| Ethnicity | −0.775 (−3.479, 1.929) | 0.566 | |||||||

| Alcohol | 0.941 (−4.749, 6.632) | 0.740 | |||||||

| Depression score | −0.017 (−0.602, 0.567) | 0.953 | |||||||

| Year of education | −0.014 (−0.979, 0.951) | 0.977 | |||||||

| Had previous history of head injury | 2.063 (−5.169, 9.294) | 0.567 | |||||||

| Presence of PTE | −4.943 (−10.795, 0.909) | 0.095 | −6.963 (−12.410, −1.515) | 0.014 | −4.376 (−10.039, 1.288) | 0.126 | −7.988 (−12.689, −3.287) | 0.002 | |

| Presence of ICH | −5.60 (−11.389, 0.189) | 0.058 | −2.603 (−7.743, 2.536) | 0.311 | −1.050 (−5.123, 3.023) | 0.603 | |||

| GCS | 0.605 (0.112, 1.098) | 0.18 | 0.145 (−0.365, 0.654) | 0.568 | 0.390 (0.023, 0.803) | 0.064 | |||

| Use of ASM | −6.774 (−10.460, −3.087) | <0.001 | −4.315 (−8.299, −0.331) | 0.035 | −2.615 (−5.833, 0.603) | 0.108 | |||

| HMGB1 changes | −0.628 (−1.154, −0.103) | 0.010 | −0.783 (−1.289, −0.277) | 0.003 | −0.557 (−1.052, −0.053) | 0.014 | −0.364 (−0.768, 0.049) | 0.038 | |

| TNF changes | −1.206 (−2.083, −0.329) | 0.008 | −1.590 (−2.318, −0.863) | <0.001 | |||||

| IL-1β changes | −0.128 (−0.256, −0.001) | 0.048 | −0.071 (−0.161, 0.019) | 0.117 | |||||

- Abbreviations: Adjusted R2, Adjusted coefficient of determination; AED, antiseizure medication; B (SE B), Regression coefficient (standard error of the coefficient); F, F-statistic; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HMGB1, High Mobility Group Box 1; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 beta; PTE, Posttraumatic epilepsy; p-value, probability value; R2, Coefficient of determination; TNF-α, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha.

3.3.1 Simple regression analysis

We performed a simple regression analysis to identify independent variables associated with changes in cognitive performance. Significant covariates with p < 0.2 for inclusion in multivariate models were PTE, ICH, GCS, HMGB1, TNF, and IL-1β changes. No multicollinearity issues were observed.

3.3.2 Multiple linear regression model 1

The first multivariate model included two independent variables: the presence of PTE and HMGB1 changes. This model significantly predicted outcomes (p = 0.003) and explained 26.1% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 0.222). Both PTE (B = −6.963, p = 0.014) and HMGB1 changes (B = −0.783, p = 0.003) were significant independent predictors, indicating the presence of PTE and lesser HMGB1 decrease were associated with poorer cognitive outcomes.

3.3.3 Multivariate model 2 (covariates added: presence of ICH, GCS, use of ASM)

In Model 2, variables included were PTE presence, HMGB1 changes, Presence of ICH, GCS, and Use of ASM and GCS. The multivariate regression analysis showed notable improvements in model fit compared to Model 1. The R2 value increased to 0.418, indicating that the predictors in this model explained approximately 41.8% of the variance in the outcome variable. Similarly, the adjusted R2 value increased to 0.335. The overall model was statistically significant (p = 0.001), and several predictors emerged as statistically significant contributors to the outcome variable, including the use of ASM (p = 0.035) and HMGB1 changes (p = 0.014). This suggests that changes in HMGB1 levels have a significant impact on the outcome variable, which is cognitive level changes, even after accounting for other confounders.

3.3.4 Multivariate model 3 (covariates added: TNF changes and IL-1β changes)

Continuing the exploration, Model 3 further enhanced the explanatory power of the regression analysis. In Model 3, variables included were PTE presence, HMGB1 changes, presence of ICH, GCS, use of ASM, GCS, TNF changes, and IL-1β changes. The R2 value substantially increased to 0.665, indicating that the predictors in this comprehensive model accounted for approximately 66.5% of the variance in the outcome variable. The adjusted R2 value remained high at 0.594. The overall model was highly statistically significant (p < 0.001), underscoring its robustness. Notably, several predictors retained statistical significance, including PTE presence (p = 0.002), HMGB1 changes (p = 0.038), and TNF changes (p < 0.001), further emphasizing their importance in predicting the outcome variable within the neuroscience context. HMGB1 changes remained a statistically significant predictor of the outcome, suggesting its significant impact on cognitive function, even after accounting for other relevant confounders like GCS, the presence of ICH and the use of ASM.

4 DISCUSSION

This study provides compelling evidence for the involvement of HMGB1 in the neuroinflammatory processes contributing to PTE and cognitive decline following TBI. In particular, HMGB1 has emerged as a crucial player in the pathogenesis of post-TBI complications, including epileptogenesis and cognitive dysfunction. Elevated HMGB1 levels observed 12 months post-TBI in PTE patients suggest a sustained neuroinflammatory response, known to exacerbate neural damage and lower the seizure threshold.5, 26-28 This supports prior studies, indicating that HMGB1 can be actively released from neurons and glia in response to tissue injury. Through its interactions with receptors such as TLR4 and RAGE, HMGB1 contributes to both systemic and CNS-specific inflammatory responses.29 These findings are particularly important for understanding the prolonged inflammatory environment that facilitates the development of PTE. Our results suggest that HMGB1 is elevated in PTE patients and correlates with inflammatory markers. However, it is important to note that this study does not provide direct evidence of CNS-specific neuroinflammation. HMGB1 is known to be produced both centrally and peripherally, and while it is involved in neuroinflammatory pathways, its systemic presence following TBI could reflect broader inflammatory responses beyond the CNS. Future studies should aim to include CNS-specific markers to directly assess neuroinflammation in PTE patients.

4.1 Role of HMGB1 in epileptogenesis

The persistent elevation of HMGB1 levels in PTE patients aligns with preclinical research showing that HMGB1 functions as a danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) protein. Once released, HMGB1 binds to TLR4 and RAGE receptors, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF, and other inflammatory mediators, which collectively promote hyperexcitability and neuronal damage.30, 31 These inflammatory pathways have been shown to create a vicious cycle, where repeated seizures result in further HMGB1 release, perpetuating chronic inflammation and facilitating the development of drug-resistant epilepsy.8

Interestingly, this study identified that HMGB1 remained significantly elevated in PTE patients compared to non-PTE individuals, suggesting that HMGB1 may be a predictive biomarker for the development of epilepsy following TBI. Previous studies have highlighted HMGB1's potential as a biomarker, particularly in identifying patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.6, 32 As an early indicator of PTE, HMGB1 could inform therapeutic strategies aimed at reducing neuroinflammation and, consequently, the risk of epileptogenesis. The presence of early seizures in some PTE patients may further suggest an increased susceptibility to chronic epileptogenesis following moderate to severe TBI. Additionally, trends indicating elevated inflammatory markers in the ASM group over time warrant further investigation into how antiseizure treatments might influence inflammatory responses.

4.2 HMGB1 and cognitive decline

The impact of HMGB1 on cognitive outcomes is another significant finding of this study. Prolonged HMGB1 elevation correlated negatively with improvements in cognitive function in PTE patients, as assessed by the Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination-III (ACE-III). This aligns with previous research showing that HMGB1-mediated neuroinflammation is associated with synaptic dysfunction, loss of neurogenesis, and cognitive deficits in several neurological conditions.9, 33 HMGB1 has also been shown to exacerbate neuronal damage in experimental models of Alzheimer's disease and TBI through the amplification of inflammatory signals, resulting in cognitive decline.9

Our data suggest that HMGB1 may serve as a biomarker for an underlying pro-inflammatory state in PTE patients, reflecting the broader neuroinflammatory environment that could contribute to cognitive decline. However, it is important to distinguish between HMGB1's role as a marker of inflammation and the direct mechanisms by which PTE drives cognitive decline. PTE patients often experience seizure-induced neuronal damage, excitotoxicity, and chronic inflammation, all of which contribute to the progression of cognitive impairment.34 Thus, HMGB1 likely acts as a marker of this inflammatory state rather than a direct cause of cognitive decline.

4.3 HMGB1 relationship with IL-1β and TNF

Our results also highlight a complex interaction between HMGB1 and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF. Although there were no significant differences in IL-1β and TNF levels between PTE and non-PTE patients over the 12-month period, correlation analysis indicated a coordinated elevation of HMGB1 with these cytokines. This aligns with previous studies identifying HMGB1 as an upstream regulator of cytokine release.10, 35 As such, HMGB1 functions both as a trigger and amplifier of the inflammatory cascade, promoting the release of IL-1β and TNF, which are critical mediators in epilepsy development.36 The interplay between HMGB1 and these cytokines may contribute to cognitive decline in patients with elevated HMGB1, as sustained inflammation has been linked to progressive neuronal damage.

Interestingly, previous studies have demonstrated that therapeutic strategies targeting HMGB1 or its receptors can attenuate neuroinflammation and reduce the expression of IL-1β and TNF, offering potential therapeutic avenues for the prevention of PTE.29, 37 The lack of significant changes in IL-1β and TNF levels in our cohort suggests that these cytokines may play more transient roles in early-stage inflammation, while HMGB1 remains a more persistent marker of chronic neuroinflammation. This aligns with prior research indicating that HMGB1 can sustain long-term inflammatory responses independently of these cytokines, promoting both epileptogenesis and cognitive dysfunction.38

Our findings revealed that moderate/severe TBI cases, particularly those with CNS pathologies like hemorrhage and brain edema, are more prone to sustained inflammation. This pro-inflammatory state may set the stage for PTE development, underscoring the relevance of TBI severity and CNS pathology in post-TBI outcomes. Given the heterogeneity of TBI outcomes and inflammatory profiles, individual differences in immune responses, potentially influenced by genetic predisposition, pre-existing conditions, or variations in post-injury treatment- may contribute to the elevated HMGB1 levels observed in PTE patients. As pre-TBI biomarker measurements are generally unattainable in clinical settings, future research should focus on longitudinal monitoring of inflammatory markers post-TBI to better understand whether HMGB1 elevation is an early predictor of PTE or a result of prolonged inflammation. Comparing PTE and non-PTE TBI patients in our cohort offers a valuable opportunity to examine these differences further. By tracking HMGB1, IL-1β, TNF, and other inflammatory markers over time, we may gain insights into the distinct inflammatory pathways involved in both PTE development and cognitive decline.

Given the interplay between these pro-inflammatory molecules, future research should focus on clarifying the mechanisms through which HMGB1 regulates cytokine release, with the aim of uncovering novel therapeutic targets to reduce inflammation and prevent PTE. Targeting HMGB1 could serve as an effective therapeutic strategy for TBI patients, potentially lowering the risk of PTE and associated cognitive impairments. Additionally, early identification of elevated HMGB1 levels post-TBI may allow for timely anti-inflammatory intervention, potentially altering the trajectory of epilepsy development and cognitive decline in affected individuals.

4.4 Study limitations

This study contributes valuable insights into HMGB1's role in neuroinflammation following TBI; however, several limitations may influence the generalizability and interpretation of the results. Firstly, the relatively small sample size, especially within the PTE group limits the statistical power of the study and restricts the depth of subgroup analyses, impacting the generalizability of findings to larger and more diverse populations. Although significant associations between HMGB1, PTE development, and cognitive decline were identified, the small number of PTE cases restricts a comprehensive exploration of underlying mechanisms and interactions. Future studies with larger, multicenter cohorts are necessary to validate these findings and enhance their relevance to a broader spectrum of TBI patients.

Secondly, while the 12-month follow-up period is sufficient to capture early-onset PTE and initial cognitive changes, it may not fully reflect the long-term progression of these conditions. Previous studies have demonstrated that both cognitive decline and epileptogenesis can occur beyond the first year after TBI, potentially overlooking late-onset cases of PTE or progressive cognitive dysfunction.28, 39 Extending the follow-up period in future studies will enable a more comprehensive assessment of delayed PTE onset and long-term cognitive outcomes. This would provide a more complete understanding of how persistent neuroinflammation influences the chronic trajectory of these post-TBI complications.

Next, while the inclusion of HMGB1, IL-1β, and TNF offered valuable insights into systemic inflammation, the scope of biomarkers in this study remains limited. These markers are well-established contributors to neuroinflammatory pathways, but they may not capture the full complexity of the inflammatory response, particularly within the CNS. The addition of CNS-specific markers, such as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and S100B, would provide a more precise assessment of neuroinflammation and allow for the differentiation between peripheral and CNS-driven inflammatory responses.40 Including a broader biomarker panel in future studies could reveal more detailed insights into the mechanistic pathways driving both PTE and cognitive decline following TBI.

Finally, potential confounding factors may have influenced the associations observed between HMGB1 levels and clinical outcomes. Variability in post-TBI medical treatments, including ASM, corticosteroids, or other anti-inflammatory therapies, could have impacted inflammatory biomarker levels. Additionally, pre-existing conditions, such as chronic inflammatory diseases or other comorbidities, may have affected baseline HMGB1 levels, complicating the interpretation of post-TBI inflammatory responses. Despite controlling for significant confounders like GCS scores and ICH through multivariate regression, residual confounding may persist. Future studies should aim to collect more comprehensive data on patient treatment regimens and medical histories to better control for these variables.

5 CONCLUSION

This study provides valuable insights into the inflammatory mechanisms underlying PTE and cognitive decline, positioning HMGB1 as a potential biomarker of systemic and neuroinflammatory processes with significant implications for understanding post-TBI complications. Future research with larger, multicenter cohorts, extended follow-up periods, and an expanded biomarker panel will be essential to validate and extend these findings. Such studies will help further elucidate the complex interactions between inflammation, epilepsy, and cognitive impairment, advancing our understanding of the pathways that contribute to post-TBI outcomes.

AUTHOR'S CONTRIBUTION

IWN: Data curation, Writing, Investigation, Formal Analysis. DM, MFS: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. CSK: Investigation, Validation, Supervision. NSC, YML: Data curation. AA, NZ: Investigation. WLC, AAS: Validation, Supervision. HJT, FF, JG: Investigation, Validation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work forms part of the first author’s Ph.D. IWN. Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley - Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Author MFS has received support from Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Science Research Strategic Grant 2021. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The Research Ethics Committee, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, approved this study (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2021-007). This study was registered with the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (27574).

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE STATEMENT

Informed consent was gained from the patient and/or the patient's caregiver or family members before recruitment.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting this study's findings are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by emailing the corresponding author upon reasonable request.