Patient-reported outcome measures and patient engagement in heart failure clinical trials: multi-stakeholder perspectives

Abstract

There are many consequences of heart failure (HF), including symptoms, impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and physical and social limitations (functional status). These have a substantial impact on patients' lives, yet are not routinely captured in clinical trials. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) can quantify patients' experiences of their disease and its treatment. Steps can be taken to improve the use of PROs in HF trials, in regulatory and payer decisions, and in patient care. Importantly, PRO measures (PROMs) must be developed with involvement of patients, family members, and caregivers from diverse demographic groups and communities. PRO data collection should become more routine not only in clinical trials but also in clinical practice. This may be facilitated by the use of digital tools and interdisciplinary patient advocacy efforts. There is a need for standardization, not only of the PROM instruments, but also in procedures for analysis, interpretation and reporting PRO data. More work needs to be done to determine the degree of change that is important to patients and that is associated with increased risks of clinical events. This ‘minimal clinically important difference’ requires further research to determine thresholds for different PROMs, to assess consistency across trial populations, and to define standards for improvement that warrant regulatory and reimbursement approvals. PROs are a vital part of patient care and drug development, and more work should be done to ensure that these measures are both reflective of the patient experience and that they are more widely employed.

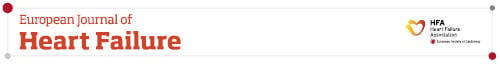

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In addition to increased risks of mortality and hospitalization, heart failure (HF) is associated with symptoms that can result in physical and social limitations, impaired quality of life, and increased rates of depression, anxiety, and stress.1, 2 While these latter outcomes have an important impact on patients' lives, they are not always captured as primary, or even secondary, endpoints in clinical trials.3, 4

One method for quantifying patients' lived experiences is through the formal collection of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) that directly assess the patient's experience, health behaviours, and the impact of the disease and its treatment on patient health status.5 There are three general components of patient health status: symptom burden, functional status (physical, mental, emotional, or social functional limitations), and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (Table 1).3 Since each patient views their own health in different ways, HRQoL is measured distinctly from symptoms or functional limitations. Thus, it is essential to assess this aspect with specifically designed tools.3

| Symptoms | Functional status | Health-related quality of life |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

- Adapted from ref.3

Patient-reported outcomes provide a unique perspective of the patient's experience of their illness and the effects of its treatment. These outcomes are relevant, not just to the patients, their families, and treating clinicians, but also to trialists, regulatory agencies, payers, and industry partners who seek to better understand these patient-centred outcomes. For example, PRO data may be used by trial sponsors to support a new product indication or labelling claim based on patient-reported treatment benefits, while payers may use these data to help determine the comparative value of different therapies.6

The Global CardioVascular Clinical Trialists (CVCT) Workshop brings together cardiovascular clinical trialists, patients, clinicians, and regulatory, government and industry representatives to discuss challenges facing cardiovascular clinical research. This paper is based on discussions at the 18th Global CVCT meeting (www.globalcvctforum.com) and aims to look at the benefits and challenges around the use of PROs to improve patient care, to inform drug development, and to aid regulatory and reimbursement decisions. The full session presentations and video recording can be accessed on the CVCT website.

Examples of patient-reported outcome measures used in heart failure

General measures of health status (e.g. 36-item Short Form Health Survey [SF-36], EuroQol-5 Dimension [EQ-5D]) can provide the clinician and patient with useful information, but are not disease-specific and are designed to quantify total impact of all current health conditions on overall physical and emotional functioning. PROMs are commonly used in HF, and a number of HF-specific PRO measures (PROMs) including the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) (Table 2), are now becoming more commonly used.4, 7 These tools not only assess HF-specific health status, but have prognostic utility, with the KCCQ shown to be more sensitive to change8, 9 and superior to the MLHFQ for the prediction of clinical outcomes (death/transplant/left ventricular assist device implantation and hospitalization).10

| Heart failure-specific questionnaires | Generic questionnaires |

|---|---|

| Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ)a | Self-Reported Dyspnoea Scale |

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)a | EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) |

| Chronic Heart Failure Questionnairea | Short Form Survey 36 or 12 |

| Care-Related Quality of Life survey for Chronic Heart Failure (CaReQoL CHF) | Patient Global Assessment |

| Chronic Heart Failure Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (CHF-PROM) | Generic Quality of Life |

| Heart Failure Somatic Awareness Scale (HFSPS) | |

| Knowledge, Attitude, Self-care Practice & Health-related Quality of Life in Heart Failure (KAPQ-HF) | |

| Left Ventricular Dysfunction Questionnaire (LVD-36) | |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Heart Failure (MSAS-HF) | |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Plus-Heart Failure (PROMIS-Plus-HF) | |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire for Severe Heart Failure (QLQ-SHF) |

It is important that PROMs be developed with patients, family members, and caregivers, and many may need ongoing updating as environmental and other issues faced by patients may change over time. It is important to consult patients from diverse demographic groups and communities.

Minimal clinically important difference

While the primary analyses of most clinical trials compare the mean differences across populations of studied patients, these can be difficult to interpret from a clinical perspective. In contrast, categorizing score changes into gradations of clinically important changes can provide deeper insight into how much better (or worse) patients are likely to feel after a particular treatment versus another. It is also necessary to understand the degree of change that is associated with increased risks of clinical events. The minimum difference in score of any outcome that patients can perceive as either beneficial or harmful is referred to as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID).11, 12 The MCID provides a method for interpreting changes in scores to help inform treatment decisions, and is also useful when planning clinical trials and calculating sample size.11, 12 However, a majority of PROs do not have established MCIDs, and studies typically report whether there is a statistically significant difference in health status between treatment groups, but do not put this in the context of MCID or larger clinically important changes.7 Population-average changes often do not differ by thresholds that are greater than the MCID for individual patients, which can make inferences about the magnitude of health status improvement with the interventions difficult to appreciate. Responder analysis, which describes the proportions of patients in each treatment arm who experience changes in their health status of varying clinical magnitudes, is one way of assessing clinical relevance in this setting, although there are arguments against this analytic approach too.13, 14 In particular, assessment at a single time point is poor evidence to classify a patient as a responder.

Estimating MCID can be done using either an expert consensus, a distribution-based method, or an anchor-based method. The distribution-based method compares changes in scores and small, moderate, and large changes in patient health status. This method relies on the statistical properties of the distribution of scores, and is used to estimate whether the magnitude of change in different groups in response to an intervention is more than would be expected from chance alone.11, 12, 15 An anchor-based determination compares the patient's numerical change in score for an outcome measure (e.g. changes in KCCQ) with an external subjective, independent evaluation of improvement (e.g. Patient Global Assessment [PGA]).11, 16

The KCCQ is the HF-specific PRO that has undergone the most extensive research to define clinically important changes.15, 17-20 These efforts have led to a general consensus that a change in KCCQ total score of >5 points has been considered to be the MCID associated with a small improvement in patient health status.17 Changes of 10 and 20 points are considered to be moderate to large, and large to very large, clinical changes in patient health status. Such thresholds can transform the mean differences in scores along a 100-point range into the proportions of patients (e.g. number needed to treat) experiencing different magnitudes of improvement with treatment. It is also important to understand the stability and time course of benefit of a given intervention; some interventions may provide benefit early while others may take longer, and similarly, some benefits may be short-term and others more sustained.21

Using an anchor-based methodology (based on PGA), and data from the FAIR-HF (Ferinject Assessment in Patients with Iron Deficiency and Chronic Heart Failure) trial, the MCID threshold for a small positive change was associated with a change in KCCQ overall summary score of 3.6.16 This was somewhat lower than the typically accepted 5-point change described above.17 This demonstrates the utility of anchor-based methodology and supports the concept that even small improvements in HRQoL of a treatment over placebo can be clinically meaningful (Table 3).22-26

| Trial22 | Difference in KCCQ-OSS with active treatment vs. control | Clinical outcomes HF hospitalization or CV death |

|---|---|---|

| FAIR-HF | +7 (SE ± 2) | Event rate decreased with treatmenta |

| DAPA-HF | +2.8 (N/A) | HR 0.74 (0.65–0.85) |

| SHIFT | +2.4 (95% CI 0.91–3.85) | HR 0.82 (0.75–0.90) |

| EMPEROR-Reduced24, 25 | +1.5 (95% CI 0.29–2.74) | HR 0.75 (0.65–0.86) |

| EMPEROR-Preserved23, 26 | +1.6 (95% CI 0.76–2.44) | HR 0.77 (0.67–0.87) |

| PARADIGM-HF | +1.3 (95% CI 0.6–2.0) | HR 0.80 (0.73–0.87) |

| TOPCAT | +1.3 (SE ± 0.4) | HR 0.89 (0.77–1.04) |

| PARAGON-HFb | +1.0 (95% CI 0.0–2.1) | RR 0.87 (0.75–1.01) |

- Adapted from refs.22-26

- CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; HR, time to first event hazard ratio; KCCQ-OSS, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary score, N/A, not available; RR, total event risk ratio; SE, standard error.

- a HRs not reported because the study was underpowered for morbidity-mortality outcomes.

- b Results for the KCCQ clinical summary score.

In addition, HRQoL may decline over the course of the disease due to deterioration of HF, but also due to other factors that may not be amenable to HF treatment, such as physical and social deterioration related to aging, non-cardiovascular comorbid conditions, and psychological factors.22, 27 Therefore, if a treatment can improve or at least stabilize a patient's HRQoL that could be considered beneficial.

Using patient-reported outcomes to improve patient care

Patient-reported outcome measures are not yet widely incorporated into routine clinical practice for patients with HF, with clinicians generally placing greater importance on echocardiographic and biomarker responses, or using non-standardized ways to obtain subjective patient feedback and gauge symptomatic treatment response.28 Yet PROs reflect what patients actually perceive and have been shown to improve the accuracy of clinicians' assessments of patients' New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification when available to the assessing physician.29 Moreover, they can be used to assess their experience and behaviours, monitor therapeutic effectiveness, and prompt discussions relating to prognosis or end-of-life care. PROs may also be useful in guiding referrals for invasive cardiac care (e.g. percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting), non-cardiac care (e.g. psychiatric care, physiotherapy, or occupational therapy, and for assessing the quality of delivered healthcare). This suggests a potential role for interdisciplinary patient advocacy efforts in support of the widespread collection, standardization and implementation of PROs in clinical practice. Quality of life should be consistently and correctly assessed and managed throughout the patient journey. Incorporating routine measurements of HRQoL in clinical practice using PROMs can help both clinicians and patients to discuss the individual's experiences, and to consider whether the treatment programme is meeting their expectations. The integration of the routine use of PROMs in clinical practice requires investing in the resources to collect, score and display the results for use by patients and their providers. Digital technologies, integrated in the electronic medical record are a promising strategy to help make this feasible. The instruments may be offered through patient portals, a smart phone app, or through tablets in clinics, thus enabling some patients to complete the questionnaires while awaiting their appointment. This is an active area of investigation and the benefits of routinely using PROMs in clinical care are just beginning in cardiology,29-31 although their benefits have been proven in cancer.32, 33 Patient organizations can provide coaching and support for patients to self-manage their condition and improve their quality of life. Formal assessments can also highlight unmet needs and areas for potential improvement in care delivery.34

Patient perspective

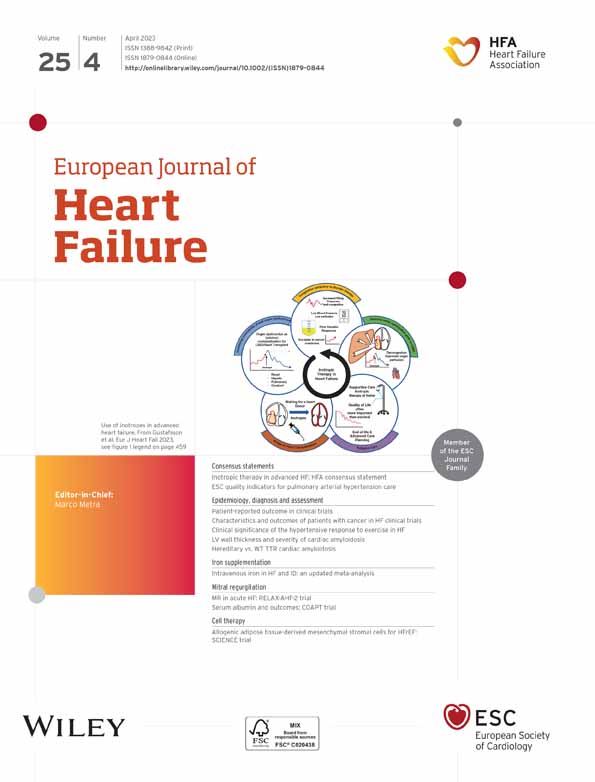

The priorities and expectations of patients and clinicians often differ. Clinicians frequently are more concerned with cardiac anatomy and physiology, reducing mortality, and specific management issues, while patients just wish to feel better.28, 35 However, both clinicians and patients generally assign high priority to improving HRQoL. Multiple studies have reported that patients often prefer a healthier life, with the majority willing to accept some decrease in longevity in return for improved health status.1, 36, 37 For example, in a survey of over 500 HF patients by the Pumping Marvellous Foundation, only 3% said that how long they live was the most important aspect of HF treatment, while 97% prioritized quality of life or both longevity and quality of life (Figure 1).28 A survey within a family medicine clinic assessing disability and quality of life among HF patients found that almost 20% had severe disability, and another 28% had moderate disability.1 The main areas affected were life activities, getting around, and participation in society.

Using patient-reported outcomes to better inform drug development and clinical trial design

Despite there being a significant increase in the inclusion of PROs in HF clinical trials over the past 20 years,4 there remains uncertainty around their interpretation and their role in the product development lifecycle. To further optimize study design requires a clearer understanding of the downstream utility of PRO data.

Trialist perspective

The inclusion of PROs in clinical trials was often thought to present multiple scientific and logistical challenges due to their fundamentally subjective nature.6, 38 Experience over time, however, has redefined the view of PROs as valid, reliable, and sensitive measures of patients' experiences. Using a PRO as a primary trial outcome complements the conduct of, and potentially reduces the need for large trials to demonstrate the less common outcome of mortality. For example, using the KCCQ overall summary score as the primary outcome measure and collecting data from mobile phones, enabled the recently completed CHIEF-HF (Canagliflozin: Impact on Health Status, Quality of Life and Functional Status in Heart Failure) trial to be conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic without a single in-person visit.39, 40 The CHIEF-HF also used PROs in the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the trial to define a more homogeneous study population.6, 40 In addition, PROMs, such as KCCQ, can be used to help identify an at risk population who is likely to respond to the treatment being tested. In HF trials, the patient population almost always includes a NYHA classification. However, clinician variability in assigning NYHA class is common,41, 42 while PRO scores have demonstrated reliability.6, 43

Compared with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), outcomes for HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) may be best defined by morbidity benefits as there continue to be few therapies that improve survival. Identifying the impact on HRQoL takes on even greater importance. Because of the unmet need in this area, a drug that improves HRQoL with or without a mortality benefit may represent a beneficial treatment and could be approved by some regulatory bodies.44 Using HRQoL and other PROs as primary endpoints in HFpEF clinical trials may be an important option to speed development of new treatments for these patients.

Since a new therapy could conceivably improve HRQoL or symptoms, but increase the risk of death/hospitalization, or vice versa, it is well understood that PROMs may be primary outcome measures of trials, provided convincing safety data are collected in the same trial and/or in adjacent trials. Hierarchical clinical composites, possibly using the win ratio statistical approach is one way of investigating the HRQoL benefits without compromising data on the risk of death/hospitalization.

Patient-reported outcomes are essential in clinical trials involving patients with chronic diseases, and as the ongoing challenges of their interpretation are being resolved, their use should continue to increase. From the trialist perspective, there is a need for standards for PRO collection and analyses to help ensure consistency across trials. Notably, the issue of missing PRO data in non-survivors needs appropriate analysis methods, such as hierarchical rank endpoints or imputation methods combining clinical events and PRO assessment.45

Industry perspective

In HF, there continues to be a need for interventions that provide HRQoL and symptomatic improvements.35 HRQoL merits a level of importance similar to traditional ‘hard’ endpoints, but there must be strong evidence to show that an intervention has a beneficial effect on HRQoL and other PROs, especially if it has a neutral effect on survival or disease progression. This is important not just from the regulatory perspective, but also from a value perspective. PROs can be used as part of the risk–benefit assessment, and help build or refute the value equation.

While the KCCQ is becoming more commonly used in HF, there are still many challenges. It is unknown whether a MCID defined in one trial population will be valid in another, for example, patients with different severities of HF, HFrEF versus HFpEF, or patients with comorbidities such as diabetes, obesity, or a depressive disorder. Choosing a KCCQ subdomain as an endpoint can be a challenge, when the mechanism of drug effects on HRQoL are not known, for example, via functional improvement and/or symptomatic improvement.

Another challenge is how to implement the KCCQ at the clinical trial sites. The tool has not been widely used by clinicians in clinical practice, and this limits the ability to rapidly screen potentially eligible patients or to supplement clinical trial results with ‘real-world’ comparative effectiveness research. Web- or app-based versions are helping in this regard. Regardless of the measurement method it is important that it remains consistent throughout a trial to minimize within-subject variability.

Overall, from the industry perspective there continues to be a need for agreement among investigators, regulatory authorities, and trial sponsors on standards for instruments, endpoints, analytical approaches, and MCIDs. It is critical for industry to foster partnerships with patients, family, and caregivers from diverse backgrounds as part of their leadership and development teams, to ensure that decisions are relevant.

Using patient-reported outcomes to better inform regulatory and reimbursement decisions

Regulatory perspective

In 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognized that even in the absence of demonstrated effects on mortality or HF hospitalizations, substantial and persistent symptomatic or functional improvement can be an acceptable endpoint for HF drug or device approval.44, 46

There remain important clinical concerns about the use of PROMs as the primary endpoint in clinical trials, particularly in open-label trials of major interventions (such as surgery) as compared with usual care. It is important, however, to realize that current PROMs do not ask general questions, such as ‘how do you feel now compared to how you felt at the start of the study’, which might clearly be susceptible to a placebo effect. In contrast, current PROMs, such as the KCCQ, ask patients to describe the frequency of their HF symptoms and functional limitations over the past 2 weeks. This may be less susceptible to a placebo effect given the very concrete nature of the items. It is noteworthy that the FDA has qualified the KCCQ and the MLHFQ as medical device development tools and the KCCQ for drug development, making approval and labelling claims more attainable with demonstration of clinically important improvements.44, 46 The European Medicines Agency guidance for chronic HF trials has not yet taken this step, but recognizes PROs as a surrogate for exercise capacity for patients who are unable to undergo exercise testing.47 Further research is needed, investigating the risk of bias in open label trials and methods to minimize the placebo effect related to the knowledge of treatment assignment, such as through multiple measurements and/or other procedures.

While trialists and industry sponsors want standards for determining a MCID for a given PROM, regulatory agencies have not yet established these thresholds. For mortality or hospitalization outcomes there is no concept of MCID, and while payers, clinicians, and patients might question the value of a small improvement, regulators only assess whether the benefits exceed the risks for approval of a treatment. However, for functional and symptomatic claims, the magnitude of change does matter. The rationale for this discrepant view may be the idea that society may benefit from a 1% decline in hospitalization, but not from a 1% improvement in global symptoms.

It is often difficult to interpret the various analyses of PROMs from clinical trials. There can be substantial variability between patient populations. Despite a high intra-class correlation coefficient in stable patients, even within a given individual, results can vary with patients showing improvement at one time point but not at another. Disease trajectories can lead to changes even in PROs. Randomization and placebo control, as well as double blinding, are critical in distinguishing benefit of an interventional treatment from the usual course of disease under standard management. This makes determining response rates a challenge. While there is no absolute threshold for clinically relevant finding, any effect larger than zero is taken into consideration. Statistically significant small changes may not be necessarily clinically meaningful, which argues for responder analyses that can clarify the proportions of patients that experience different magnitudes of clinical change.

Overall, there is a need to increase the understanding of the importance of specific HRQoL benefits. Answering questions such as: When is a new therapy approvable if the benefit versus existing care is solely an improvement in HRQoL? What if this therapy has less safety documentation and certainty than established therapies with years of experience? Will patients and clinicians find the documented HRQoL measures convincing enough to prefer the new therapy? Providing clear answers to industry decision-makers will increase the likelihood that better and lower-risk programmes can be designed from early drug development and facilitate prioritization and investment into HRQoL-oriented therapies.

Health economics/payer perspective

Assessing the incremental health benefits of an intervention relative to its incremental net long-term costs is often used by payers to determine treatment value, with PROs being an important component of the numerator in the value equation.48 Payers make decisions that maximize both patient and population health outcomes, while operating within the context of finite resources. It is important that appropriate endpoints for capturing clinical, PRO, and economic outcomes are incorporated at the trial stage to subsequently inform reimbursement decisions.

Given the established association between clinical outcomes (e.g. survival, hospitalization) and HF-specific PROMs, such as the KCCQ, such measures can be used to quantify clinical risk. The HF-specific PROMs allow quantification for decisions within HF, but the results of generic assessment tools are also crucial for payers who have to consider reimbursement decisions not just for HF but other cardiovascular conditions as well. For example, the FAIR-HF trial included not only the HF-specific self-reported patient global assessment and the KCCQ, but also the generic EQ-5D, which helps in the determination of treatment value across disease states.49 However, in studies that do not collect such utility assessments, the KCCQ can be mapped to predict EQ-5D utilities, which can be used to support cost-effectiveness analyses.50, 51 However, at least in HF, we are yet to see payers willing to pay a premium for a new therapy based only on improvement in PROs.

Patient-reported outcomes are used both before, during, and after the introduction of treatments to support regulatory and reimbursement approvals. For example, the DAPA-HF (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse-Outcomes in Heart Failure) trial showed a reduction in the risks of mortality and hospitalization for HF, and improvements in symptoms.52 An economic evaluation was conducted using KCCQ and other outcomes to capture the progression of disease and the impact of different treatment modalities on both the clinical outcomes and the patient-relevant outcomes.53 Results suggested that dapagliflozin did represent value for money for the treatment of HFrEF in the UK, German and Spanish healthcare systems.

In health economic evaluation of treatment value, PROs can play an important role in assessing the real-world relationship between patient health status, medication adherence, treatment effectiveness and clinical outcomes. In HF, lower HRQoL and symptoms of depression may be associated with non-adherence to HF medications.54 Non-adherence may be associated with poorer patient outcomes (e.g. HF mortality) and increased health system burden (e.g. increased frequency of hospitalization for HF).55

Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical practice guidelines

Despite recognition of the importance of functional capacity and HRQoL for patients with HF, recommendations in HF guidelines continue to be based predominantly on morbidity and mortality outcomes.56, 57 Recommendations based on PRO data are generally not class I, even when the data fulfil the criterion of ‘data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses’. For example, in the 2021 ESC HF guidelines the recommendations relating to iron supplementation continue to be class IIa (‘should be considered’) rather than class I (‘is recommended’ or ‘is indicated’).56

This is likely related to ongoing issues around standards for reporting and interpreting PRO data. In HF clinical trials, the NYHA class is not reported as a mean for each treatment arm, but rather as the proportion of patients within each NYHA class. This categorization facilitates understanding of the applicability of the trial to a certain patient population. Yet this approach is not used for HRQoL variables, with each trial reporting their own mean scores for the PROM used. An established and agreed-upon range for PROMs such as KCCQ or MLHFQ scores would enable more standardized reporting and interpretation of PRO data.15

Relevant questions to be considered include how to assess PRO fluctuations to identify responders and how to convert patient- and population-improvement concepts into interpretable results for action by the clinician, including how to define the MCID for within-patient changes in different patient populations. Until these questions are answered, guideline recommendations will continue to receive a lower-class rating despite a high level of evidence. One approach would be to issue a class I recommendation where warranted especially in rare diseases, but one that is accompanied with a specific statement acknowledging the lack of long-term mortality/morbidity data. Such a shift in guidance would further acknowledge the importance of improvements in PROs.

Beyond patient-reported outcomes: involving patients in clinical trial design and execution

The focus of PROMs has been on developing and validating instruments that have optimal test characteristics. However, this often fails to consider the user-friendliness of these tools. Although using PROMs is a step in the right direction, it is important to ensure that they are being designed, and this type of data is being collected, from a diverse population that is representative of individuals with the disease. The burden of disease extends to family members and caregivers, and their perspective should also be solicited when designing PROMs. Having comprehensive representation of patients in clinical trials will ensure that HRQoL, efficacy and safety data are more relevant, and generalizable to broader populations.

‘Patient-centric’, the concept of having the patient at the centre of clinical research and care, underscores that the goal of generating new knowledge is to improve patient care and outcomes. However, for some people this implies patients in the middle with things going on around them. Patient-centred research is meant to anchor research on the values and priorities of patients and to include them as partners, but true patient partnership continues to be underused. Even in Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funded studies, engagement often included only passive consultants, while true collaboration and shared leadership occurred in only 37% of trials. A report from the PCORI funded ADAPTABLE (Aspirin Dosing: A Patient-centric Trial Assessing Benefits and Long-term Effectiveness) study concluded that patients must be an active part of the steering committee, and that true patient engagement requires not just one or two ‘token’ patients but a group of at least five or six diverse patients to produce effective, shared ideas and confidence.58 It is critical that patients are seen as partners in their healthcare management and in clinical trials from development through trial design, execution, and dissemination.

The CVCT Forum has a long history of integrating patients as speakers and panellists during its annual meetings (www.globalcvctforum.com/patient-trialists). Each patient brings their own perspectives and priorities, their own experiences and knowledge about their disease to the table, and thus they are one of the most valuable resources in the development of improved treatments for HF.

Summary

Steps are needed to address the challenges around the standardization and use of PROs in cardiovascular trials, regulatory and payers' decisions and patient care. One of the most important aspects is to ensure that patients, family members, and caregivers from diverse demographic groups and communities are involved in the development of PROMs, as well as the design, analysis and interpretation of PROs in clinical trials. There is a need for standardization not only of the PROM instruments, but also in procedures for analysis, interpretation and reporting of PRO data. A summary of recommendation is shown in the Graphical Abstract and Table 4.

| PROMs |

|

| PRO use in clinical care |

|

| PROs in clinical trials |

|

| PRO data analysis |

|

| PRO results reporting and interpretation |

|

| International regulatory PRO guidance |

|

| International payer valuation methods of PRO benefits |

|

- HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; PRO, patient-reported outcome; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

Acknowledgements

This article was generated from discussions at the 18th Global Cardiovascular Clinical Trialists (CVCT) Forum held online in December 2021 (https://www.globalcvctforum.com/). The CVCT Forum is a strategic workshop for high level dialogue between clinical trialists, industry representatives, regulatory authorities, and patients. The authors would like to thank Pauline Lavigne and Steven Portelance (unaffiliated, supported by the CVCT Forum) for contributions to writing, and editing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: F.Z.: personal fees for trial oversight committees, advisory boards, or speakers' bureau from Acceleron, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biopeutics, Boehringer, Cardior, Cereno Scientific, Cellprothera, CVRx, G3 Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Merck AG, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, and Vifor Fresenius; is co-founder of CardioRenal and CVCT. J.B.: consulting fees from Abbott, Adrenomed, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, Array, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, CVRx, G3 Pharma, Impulse Dynamics, Innolife, Janssen, LivaNova, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Relypsa, Roche, Sequana Medical, and Vifor; and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus from Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim-Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Janssen. K.J.: employment with Vifor Pharma. R.K.: grants or contracts (jointly with institution) from Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca, and an educational grant paid directly to the institution from Novartis; speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Amarin, and AstraZeneca; leadership roles on various committees for the ESC (Science Committee, Allied Professions Task Force), UK Clinical Pharmacy Association (Cardiology Committee Chair), Pumping Marvelous Charity (Clinical Board Member), and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Heart Failure Quality Standards). L.M.: support from the Italian Ministry of Health Ricerca Corrente IRCCS Multimedica; participation in data safety monitoring boards or advisory boards for Pfizer, Bayer, Roche Diagnostics, and MSD. R.M.: salary support from SmartPatients.com. L.R.: employment with Bayer AG; stock or stock options from Bayer AG. H.G.C.V.S.: grants or contracts from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. C.Y.: participation on various NIH and NHLBI sponsored clinical trial and clinical research network oversight committees; served as President (past) of the American Heart Association (AHA); prior spousal employment with Abbott Labs, Inc. Murakami: Employment with Eli Lilly and Company; stock or stock options from Eli Lilly and Company. J.A.S.: grants or contracts from Janssen, Myokardia/Bristol Meyers Squibb, Abbott Vascular, and the National Institutes of Health; holds the copyright to the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, Seattle Angina Questionnaire, and the Peripheral Artery Questionnaire; consulting fees from Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Imbria Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck, Terumo, Bayer, and AstraZeneca; and a leadership or fiduciary role with Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Kansas City. All other authors have nothing to disclose.