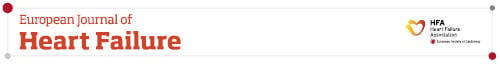

Use of mechanical circulatory support in patients with non-ischaemic cardiogenic shock

ABSTRACT

Aims

Despite its high incidence and mortality risk, there is no evidence-based treatment for non-ischaemic cardiogenic shock (CS). The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) for non-ischaemic CS treatment.

Methods and results

In this multicentre, international, retrospective study, data from 890 patients with non-ischaemic CS, defined as CS due to severe de-novo or acute-on-chronic heart failure with no need for urgent revascularization, treated with or without active MCS, were collected. The association between active MCS use and the primary endpoint of 30-day mortality was assessed in a 1:1 propensity-matched cohort. MCS was used in 386 (43%) patients. Patients treated with MCS presented with more severe CS (37% vs. 23% deteriorating CS, 30% vs. 25% in extremis CS) and had a lower left ventricular ejection fraction at baseline (21% vs. 25%). After matching, 267 patients treated with MCS were compared with 267 patients treated without MCS. In the matched cohort, MCS use was associated with a lower 30-day mortality (hazard ratio 0.76, 95% confidence interval 0.59–0.97). This finding was consistent through all tested subgroups except when CS severity was considered, indicating risk reduction especially in patients with deteriorating CS. However, complications occurred more frequently in patients with MCS; e.g. severe bleeding (16.5% vs. 6.4%) and access-site related ischaemia (6.7% vs. 0%).

Conclusion

In patients with non-ischaemic CS, MCS use was associated with lower 30-day mortality as compared to medical therapy only, but also with more complications. Randomized trials are needed to validate these findings.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is an acute haemodynamic comprise of cardiac origin, which triggers severe tissue malperfusion. It may present on a wide spectrum of severity, ranging from beginning to in-extremis CS, and can be caused by multiple diseases.1, 2 Despite extensive research efforts, the overall mortality burden of CS has remained high.3, 4

Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices such as veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) therapy and percutaneous left ventricular assist devices (pLVADs) have recently been introduced for CS treatment.5 These devices aim to treat CS by providing haemodynamic support, thereby allowing for sufficient tissue perfusion until native heart recovery.5, 6 Additionally, pLVADs provide direct unloading of the left ventricle (LV), which might facilitate native heart recovery.7 However, these haemodynamic benefits need to be evaluated in the context of potential complications, which are linked to the use of MCS, and which might ultimately mitigate the potential treatment benefit.5, 8-10 For this reason, several prospective, randomized, controlled trials are currently ongoing, evaluating the efficacy and safety of MCS in CS (DanGer-SHOCK and ULYSS for pLVAD, ECLS-SHOCK for VA-ECMO, ANCHOR and UNLOAD ECMO for VA-ECMO with LV unloading, ALTSHOCK-2 for intra-aortic balloon pump).

However, all but two of these trials (ALTSHOCK-2 and UNLOAD ECMO) exclusively enroll patients with CS caused by an acute myocardial infarction, and exclude patients with non-ischaemic CS, although 50% of all CS is of non-ischaemic cause and patients presenting with non-ischaemic CS have a comparably high mortality risk as those presenting with CS due to acute myocardial infarction.3, 11-13 Consequently, there is a strong need for evidence on treatment of non-ischaemic CS.13

The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of MCS in patients with non-ischaemic CS, focusing on its association with 30-day all-cause mortality and different safety endpoints in a propensity-score matched analysis based on an international, multicentre, observational registry.

Methods

This study was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by local ethics committees and internal review boards. The need for informed consent was waived by the main ethics committee as this was a retrospective analysis and only completely anonymized data were collected.

Design

Consecutive patients with non-ischaemic CS treated between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2021 from 16 tertiary care centres with dedicated experience in MCS use and availability of pLVAD/VA-ECMO in five countries were retrospectively enrolled (NCT03313687). Only patients treated with VA-ECMO or pLVAD (Impella® device family, Abiomed, Danvers, MA, USA), but not with an intra-aortic balloon pump, or without any MCS were considered for this study. CS was defined at the discretion of the local investigator, although the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) CS classification was suggested for guidance, and its application in the registry was based on review of medical records and medical notes made at the time of presentation.1 Non-ischaemic CS type was defined as either severe de-novo or acute-on-chronic heart failure, depending on the patient's medical history (e.g. patients with a prior diagnosis of heart failure, either from outpatient or inpatient visits, were classified as acute-on-chronic heart failure, and vice versa).

Patients with acute myocardial infarction, with CS primarily caused by right heart failure (e.g. acute pulmonary embolism), with VA-ECMO assisted resuscitation and with post-cardiotomy CS were excluded.

Treatment was left at the discretion of the local investigators and in accordance with local guidelines. As there is no obvious definition for a common baseline in non-ischaemic CS (such as time of revascularization in ischaemic CS), and especially because only some patients, but not all, were treated with MCS (which usually is a marker for clinical deterioration as compared to no MCS use), different baseline definitions were used based on treatment with versus without MCS (and for patients without MCS, based on hospital status). Baseline was defined as the time of implantation of the first MCS device (for patients treated with MCS), as the time of hospital admission (for outpatients not treated with MCS), or time of admission to the intensive care unit (for inpatients not treated with MCS). All variables representing disease severity (e.g. lactate, pH, ejection fraction [EF]) were captured at this time point, but with a 12 h window to capture the worst value for a given variable (e.g. the highest lactate value within 6 h prior to until 6 h after admission to the intensive care unit for an inpatient not treated with MCS was obtained). Information on other, non-time dependent variables (e.g. comorbidities) and endpoints were captures throughout the hospital stay.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was 30-day mortality. For the safety endpoints, bleeding complications (severe/moderate bleeding defined by GUSTO; intracerebral bleeding/haemorrhagic stroke on computed tomography; intervention due to bleeding; haemolysis, defined as lactate dehydrogenase ≥1000 U/L and haptoglobin <0.3 g/L in two samples within 24 h), ischaemic complications (ischaemic stroke on computed tomography; intervention due to access site-related ischaemia; laparotomy) and other complications (hypoxic brain damage on computed tomography; renal replacement therapy; sepsis, defined as systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria and ≥2 positive blood cultures) were assessed.

Statistics

Missing data were handled by multiple imputations with chained equations using the R-package mice with 10 imputed data sets (Table 1 indicates the variables used for the imputation).14 In the imputed datasets, a logistic regression model was used to calculate the propensity scores for MCS, which were then averaged. The following variables were used for the propensity scores: age, sex, severe de-novo versus acute-on-chronic heart failure, prior cardiac arrest and duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, baseline lactate, baseline pH, vasopressor use, SCAI CS class, use of mechanical ventilation and baseline EF. Based on these propensity scores, patients treated with were matched 1:1 to patients treated without MCS by using the nearest neighbour method with a caliper of 0.1 and no replacement. The balance in potential confounders between the study groups was evaluated based on the standardized mean difference, and a value below 0.10 was considered no relevant difference.

| Unmatched study cohort | Matched study cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No MCS (n = 504) | MCS (n = 386) | Missing data | p-value | No MCS (n = 267) | MCS (n = 267) | SMD | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, years | 67.58 (15.45) | 56.80 (14.95) | 0% | <0.01 | 61.85 (16.14) | 59.84 (14.39) | 0.13 |

| Age, categorizeda | <0.01 | 0.02 | |||||

| ≤65 years | 186 (36.9) | 271 (70.2) | 156 (58.4) | 158 (59.2) | |||

| >65 years | 318 (63.1) | 115 (29.8) | 111 (41.6) | 109 (40.8) | |||

| Female sexa | 165 (32.7) | 89 (23.1) | 0% | <0.01 | 67 (25.1) | 71 (26.6) | 0.03 |

| Medical history | |||||||

| Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 148 (63.0) | 148 (63.0) | 51% | <0.01 | 72 (53.7) | 70 (50.0) | 0.08 |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 131 (26.0) | 128 (33.2) | 0.1% | 0.03 | 71 (26.6) | 77 (28.8) | 0.05 |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy | 69 (13.7) | 55 (14.3) | 0.2% | 0.89 | 40 (15.0) | 33 (12.4) | 0.08 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 246 (50.8) | 164 (42.9) | 2.7% | 0.03 | 131 (50.8) | 118 (44.9) | 0.11 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 167 (33.7) | 90 (23.7) | 1.7% | <0.01 | 86 (33.2) | 68 (26.0) | 0.15 |

| Arterial hypertension | 320 (65.0) | 194 (51.2) | 2.1% | <0.01 | 148 (57.8) | 142 (54.4) | 0.07 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 45 (9.2) | 17 (4.5) | 2.2% | 0.01 | 24 (9.2) | 12 (4.6) | 0.18 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27 [24–31] | 27 [24–31] | 3.1% | 0.99 | 27 [24–31] | 27 [24–31] | 0.03 |

| Prior revascularization | 129 (27.6) | 80 (21.6) | 5.7% | 0.06 | 63 (24.9) | 65 (25.5) | 0.01 |

| Sum of comorbidities | 2.1 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.4) | 12.8% | <0.01 | 2.0 (1.4) | 1.8 (1.4) | 0.14 |

| Clinical presentation | |||||||

| Cause of cardiogenic shocka | 0.1% | 0.65 | 0.06 | ||||

| Acute-on-chronic heart failure | 262 (52.0) | 207 (53.8) | 149 (55.8) | 140 (52.6) | |||

| De-novo heart failure | 242 (48.0) | 178 (46.2) | 118 (44.2) | 126 (47.4) | |||

| SCAI cardiogenic shock classa | 0% | <0.01 | 0.09 | ||||

| C | 260 (51.6) | 128 (33.2) | 111 (41.6) | 111 (41.6) | |||

| D | 118 (23.4) | 142 (36.8) | 84 (31.4) | 94 (35.2) | |||

| E | 126 (25.0) | 116 (30.1) | 72 (27.0) | 62 (23.2) | |||

| LVEF, % | 24.52 (11.52) | 20.85 (10.43) | 22.7% | <0.01 | 22.89 (11.54) | 22.02 (10.40) | 0.08 |

| LVEF, categorizeda | <0.01 | 0.05 | |||||

| ≤20% | 185 (53.5) | 225 (65.8) | 122 (62.6) | 141 (60.0) | |||

| >20% | 161 (46.5) | 117 (34.2) | 73 (37.4) | 94 (40.0) | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 82.43 (17.79) | 79.50 (20.35) | 2.6% | 0.03 | 82.75 (19.05) | 79.84 (20.62) | 0.15 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 100 [78–127] | 101 [80–124] | 1.5% | 0.94 | 105 [80–128] | 102 [80–125] | 0.10 |

| Vasopressor usea | 465 (92.4) | 346 (89.6) | 0.1% | 0.18 | 241 (90.3) | 244 (91.4) | 0.04 |

| Maximum catecholamine dose, μg/kg/min | 36 [12–120] | 35 [12–83] | 3.5% | 0.27 | 35 [12–109] | 30 [11–83] | 0.07 |

| Prior cardiac arresta | 4.0% | 0.50 | 0.04 | ||||

| <10 min | 56 (11.7) | 37 (9.8) | 27 (10.8) | 31 (12.0) | |||

| ≥10 min | 147 (30.8) | 109 (29.0) | 78 (31.2) | 77 (29.8) | |||

| No cardiac arrest | 275 (57.5) | 230 (61.2) | 145 (58.0) | 150 (58.1) | |||

| Mechanical ventilationa | 296 (60.8) | 275 (72.2) | 2.5% | <0.01 | 173 (66.5) | 181 (69.1) | 0.06 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 210.52 (117.94) | 208.11 (122.98) | 29.9% | 0.80 | 201.83 (116.76) | 211.25 (119.71) | 0.08 |

| pH | 7.28 [7.17–7.37] | 7.30 [7.20–7.39] | 3.4% | 0.02 | 7.29 [7.18–7.38] | 7.30 [7.20–7.38] | 0.03 |

| pH, categorizeda | 0.02 | 0.07 | |||||

| ≤7.29 | 265 (54.9) | 175 (46.4) | 133 (52.2) | 127 (48.8) | |||

| >7.29 | 218 (45.1) | 202 (53.6) | 122 (47.8) | 133 (51.2) | |||

| Lactate, mmol/l | 6.5 [3.5–9.5] | 6.3 [3.7–9.9] | 8.4% | 0.71 | 6.3 [3.3–9.8] | 6.6 [3.8–10.2] | 0.10 |

| Lactate, categorizeda | 0.80 | 0.05 | |||||

| ≤6.4 mmol/L | 226 (49.6) | 182 (50.7) | 121 (51.3) | 122 (48.8) | |||

| >6.4 mmol/L | 230 (50.4) | 177 (49.3) | 115 (48.7) | 128 (51.2) | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.71 [1.25–2.50] | 1.77 [1.32–2.60] | 1.8% | 0.19 | 1.70 [1.30–2.50] | 1.70 [1.30–2.48] | 0.09 |

- Categorical variables are shown as counts (frequencies) and compared by the χ2 test. Continuous variables are shown as mean (± standard deviation) and compared by t-test when normally distributed; and shown as median (interquartile range) and compared by Mann–Whitney U test when non-normally distributed.

- LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; SCAI, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions; SMD, standardized mean difference.

- a Variables included in the multiple imputation model (together with MCS use, centre and year of enrolment as well as the primary outcome) and used for the calculation of the propensity scores. The balance in potential confounders between the matched study groups was evaluated based on the SMD, and a value below 0.10 was considered no relevant difference. Missing data for the matched study cohort are shown in online supplementary Table S1. Maximum catecholamine dose was calculated as follows: maximum dobutamine dose (μg/kg/min) + (maximum epinephrine dose [μg/kg/min] + maximum norepinephrine dose [μg/kg/min]) × 100.

Categorical variables are shown as counts (frequencies) and compared by the χ2 test. Continuous variables are shown as mean (± standard deviation) and compared by t-test when normally distributed; and shown as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and compared by Mann–Whitney U test when non-normally distributed.

In the unmatched and matched study cohorts, the Kaplan–Meier method was used to obtain crude 30-day mortality risk in both groups and a Cox regression model was fitted to evaluate the association of MCS use with 30-day mortality and in-hospital mortality. Proportional hazards assumption for MCS use was assessed based on Schoenfeld residuals and met.

To evaluate the association between MCS use and mortality risk in pre-specified subgroups, Cox regression models including the interaction between MCS use and the variable representing the subgroup were fitted in the matched study cohort. Additionally, a Cox regression model was fitted in the matched study cohort to assess the association between LV unloading (e.g. treatment with pLVAD alone or pLVAD + VA-ECMO vs. treatment without any MCS or VA-ECMO alone) and mortality risk.

To evaluate the association between MCS use and severe bleeding, a logistic regression model was fitted in the matched study cohort as well as in pre-specified subgroups of interest (by including the interaction term between MCS use and the variable representing the subgroup).

Lastly, the association between MCS use and implantation of a durable LVAD or heart transplantation was assessed by fitting a logistic regression model.

Statistical analyses were performed using R 3.5.3.15 A p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Unmatched study cohort

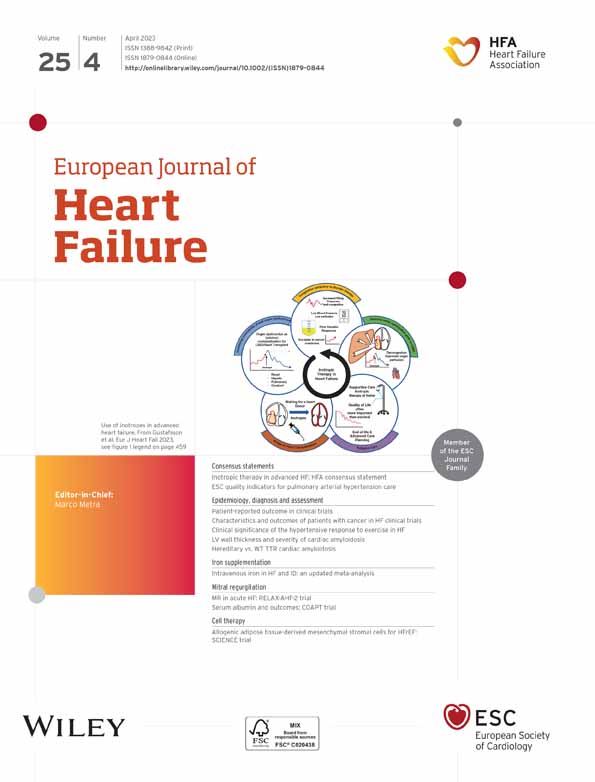

A total of 890 patients with non-ischaemic CS were considered, of whom 386 (43%) were treated with and 504 (57%) without MCS (Figure 1).

In this unmatched cohort, mean age was 63 (± 16) years and 254 (29%) of the patients were female. A total of 420 (47%) of patients presented with severe de-novo heart failure, and 469 (53%) with acute-on-chronic heart failure; 349 (39%) had prior cardiac arrest, 571 (66%) were on mechanical ventilation, EF was 22 (± 11)%, baseline lactate was 6.4 (IQR 3.5–9.7) mmol/l and baseline pH was 7.29 (IQR 7.18–7.38).

Patients treated with MCS in the unmatched cohort were younger (57 vs. 68 years) and less frequently female (23% vs. 33%), presented with more severe CS (e.g. higher SCAI CS class) and had a lower EF (21% vs. 25%). MCS use was as follows: 163 (42%) patients were treated with pLVAD only, 136 (35%) with VA-ECMO only and 89 (23%) with pLVAD + VA-ECMO; and no patient was treated with an intra-aortic balloon pump.

Matched study cohort

After matching, 534 patients treated with versus without MCS were paired. Distribution of characteristics used for the matching was well balanced between both groups (Table 1).

In patients with MCS treatment from the matched cohort, device use was as follows: 132 patients (49%) were treated with pLVAD only (13 [9%] with an Impella 2.5, 118 [86%] with an Impella CP and 7 [5%] with an Impella 5.0/5.5), 81 (30%) patients were treated with VA-ECMO only and 55 (21%) patients were treated with a pLVAD + VA-ECMO (11 [16%] Impella 2.5, 53 [78%] Impella CP and 4 [6%] Impella 5.0/5.5). Median duration of treatment was 3 (IQR 1–6) days for pLVAD and 3 (IQR 0–7) days for VA-ECMO. Implantation of a durable LVAD or heart transplantation was observed in 29 (11%) patients treated with versus 11 (4%) patients treated without MCS (odds ratio 2.87, 95% CI 1.44–6.13).

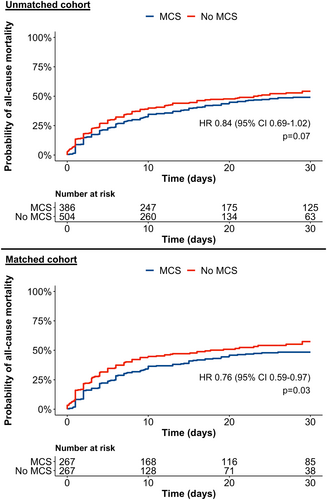

Association between mechanical circulatory support and 30-day all-cause mortality

In the unmatched study cohort, 414 (46.5%) patients died during a median follow-up of 13 (IQR 4–25) days. Crude 30-day mortality risk in patients treated with versus without MCS was 49.1% (95% CI 43.5–54.0%) versus 54.2% (95% CI 48.5–59.3%). The corresponding hazard ratio (HR) of MCS use for 30-day mortality was 0.84 (95% CI 0.69–1.02, p = 0.07; Figure 2), and 0.86 (95% CI 0.71–1.04, p = 0.11) for in-hospital mortality.

In the matched cohort, 258 (48.3%) patients died during a median follow-up of 12 (IQR 4–27) days. Crude 30-day mortality risk in patients treated with versus without MCS was 48.41% (95% CI 40.2–55.4%) versus 54.9% (95% CI 48.5–60.4%). The corresponding hazard ratio (HR) of MCS use for 30-day mortality was 0.76 (95% CI 0.59–0.97, p = 0.03; Figure 2), and 0.77 (0.61–0.98, p = 0.03) for in-hospital mortality.

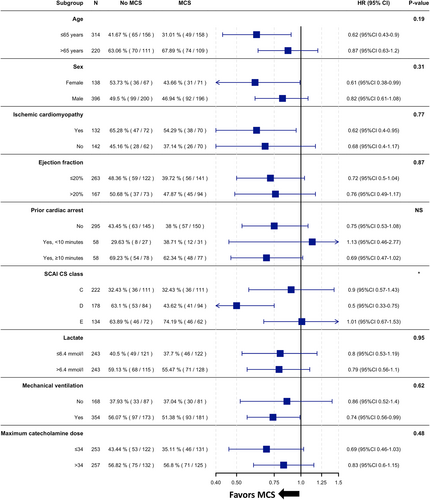

The association between MCS use and lower mortality was observed across most subgroups of interest (e.g. older vs. younger patients, females vs. males, patients with vs. without prior cardiac arrest and patients with higher vs. lower EF). However, a significant interaction was observed regarding CS severity, where the association between MCS use and lower 30-day mortality was only observed in those with deteriorating CS (SCAI CS class D), but not in those with classic CS or in-extremis CS (SCAI CS classes C and E; Figure 3).

Among patients treated with versus without LV unloading (e.g. patients with pLVAD or pLVAD + VA-ECMO vs. those treated without any MCS or VA-ECMO alone; online supplementary Table S2) from the matched study cohort, crude 30-day mortality risk was 48.4% (95% CI 40.2–55.4%) versus 54.9% (95% CI 48.5–60.4%), resulting in a HR for active LV unloading of 0.79 (95% CI 0.61–1.03, p = 0.08; online supplementary Figure S1).

Association between mechanical circulatory support and safety endpoints in the matched cohort

In the matched study cohort, complications occurred more frequently in patients treated with versus without MCS, including severe bleeding (16.5% vs. 6.4%, p < 0.01), interventions due to bleeding (12.7% vs. 2.3%, p < 0.01), haemolysis (15.1% vs. 1.1%, p < 0.01) and interventions due to access site-related ischaemia (6.7% vs. 0%, p < 0.01). Also, need for renal replacement therapy (49.4% vs. 31.1%, p < 0.01) and sepsis (27.7% vs. 16.9%, p < 0.01) were observed more frequently in patients with MCS (Table 2).

| No MCS (n = 267) | MCS (n = 267) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding complications | |||

| Moderate bleeding | 46 (17.2) | 108 (40.4) | <0.01 |

| Severe bleeding | 17 (6.4) | 44 (16.5) | <0.01 |

| Intracerebral bleeding | 4 (1.5) | 4 (1.5) | 0.22 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 0.45 |

| Intervention due to bleeding | 6 (2.3) | 34 (12.7) | <0.01 |

| Haemolysis | 3 (1.1) | 40 (15.1) | <0.01 |

| Ischaemic complications | |||

| Ischaemic stroke | 12 (4.6) | 21 (8.5) | 0.11 |

| Intervention due to access site-related ischaemia | 0 (0.0) | 18 (6.7) | <0.01 |

| Laparotomy due to abdominal compartment or bowel ischaemia | 3 (1.1) | 15 (5.6) | <0.01 |

| Other complications | |||

| Hypoxic brain damage | 24 (9.1) | 24 (9.7) | 0.94 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 83 (31.1) | 132 (49.4) | <0.01 |

| Sepsis | 45 (16.9) | 74 (27.7) | <0.01 |

- Variables are shown as counts (frequencies) and compared by the χ2 test.

- MCS, mechanical circulatory support.

When assessing the likelihood of severe bleeding with MCS use across several subgroups, a consistent association between MCS use and a higher likelihood of severe bleeding was observed across most subgroups of interest. However, a significant interaction was observed regarding age and use of catecholamines, where the association between MCS use and a higher likelihood of severe bleeding was only observed in younger but not in older patients, and in patients with a lower but not in those with a higher maximum catecholamine dose (Figure 4).

Discussion

In this retrospective, multicentre, international, propensity score-matched study of patients with non-ischaemic CS (e.g. CS caused by severe de-novo or acute-on-chronic heart failure), MCS was associated with a 24% relative risk reduction in the primary endpoint of 30-day mortality. This association was consistent across most subgroups except when considering CS severity, suggesting a risk reduction especially in patients with deteriorating CS. However, use of MCS was also linked to more complications, especially bleeding complications and access site-related ischaemia.

Mechanical circulatory support for the treatment of non-ischaemic cardiogenic shock

Although non-ischaemic CS occurs frequently and is linked to a high mortality risk, there is currently no specific evidence-based treatment. MCS could fill this gap, as it restores tissue perfusion and can even directly unload the LV.16 This has the potential for stopping the downward spiral of CS and potentially even facilitating native heart recovery. However, it is currently unclear how MCS impacts on non-ischaemic CS, and large heterogeneity exists regarding their actual use in non-ischaemic CS.17 Additionally, there is a link between MCS and complications, which might mitigate potential benefits.8-10, 18 Unfortunately, previous randomized trials have mainly focused on CS caused by acute myocardial infarction, and have specifically excluded patients with non-ischaemic CS, so that data on this topic are lacking.13

This study used a large, retrospective, international, multicentre database to evaluate MCS use in non-ischaemic CS. As a major strength, the enrolling centres specifically included patients in whom severe de-novo or acute-on-chronic heart failure was the main pathology of CS, but not acute myocardial infarction. Within this cohort, 30-day mortality risk was high (46.5%), and comparable between patients treated with versus without MCS. However, baseline characteristics indicated that MCS was more frequently used in patients with more severe CS and those with a lower EF. Therefore, propensity-score matching was used to account for this, resulting in a well-balanced matched study cohort.

In the matched cohort, use of MCS was associated with a 24% relative risk reduction in 30-day mortality, and a higher likelihood to bridge a patient to durable LVAD implantation or heart transplantation. A potential explanation for this might be MCS devices restoring tissue perfusion during CS, allowing native heart recovery, or bridging to long-term therapies. This assumption is supported by two smaller case series which reported haemodynamic stabilization with MCS use in non-ischaemic CS.19, 20 Intriguingly, this might indicate that MCS could improve outcomes by avoiding potentially noxious catecholamines. A previous meta-analysis of more than 2500 patients in CS showed that use of epinephrine triples mortality, which might be mediated by a higher risk of refractory CS.21, 22 Also, a randomized trial comparing dobutamine versus norepinephrine for the treatment of shock showed no differences in mortality risk between study groups, but indicated a higher risk of arrhythmias with dobutamine.23 Similarly, a recent study has reported higher CS mortality risk with norepinephrine use.24 Consequently, it has been suggested to use catecholamines primarily for very short durations and as a bridge to further therapies, including MCS, in CS.25 In this regard, it is also noteworthy that the average duration of MCS runs was shorter than in previous studies (∼3 vs. ∼5 days), which might relate to the underlying condition being non-ischaemic CS in this study versus mostly ischaemic CS in other studies.18

Importantly, the results on MCS use in non-ischaemic CS are contrasted by an analysis from the National Inpatient Sample.26 Here, pLVAD treatment in non-ischaemic CS was associated with higher mortality as compared to treatment with intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation. However, although this study was based on a large database (n = 18 032), no CS specific baseline characteristics were available for matching or adjustment (e.g. no lactate or SCAI CS classes).26 Based on the observations of the present study (e.g. higher CS severity and lower EF in patients treated with MCS), it is therefore likely that these results are confounded by an indication bias, e.g. that pLVADs might have been used in more severely diseased patients, without accounting for this in the analyses.

Nevertheless, the results of our study are still based on non-randomized data, and the findings should therefore only be seen as hypothesis-generating. However, given the high mortality risk of non-ischaemic CS and the lack of effective treatments, this should be seen as a strong call for randomized controlled trials of MCS in non-ischaemic CS. A first step in this direction is the randomized ALTSHOCK-2 trial: based on promising haemodynamic and clinical data, it has been initiated to test the hypothesis that intra-aortic balloon pump use, as compared to use of vasoactives only, improves outcomes in patients with non-ischaemic CS.27-29 Other trials, such as the recently published ECMO-CS trial, which showed a neutral mortality outcome with early VA-ECMO use, as well as the ongoing UNLOAD ECMO trial, testing VA-ECMO use with versus without active LV unloading, will also add to this, although they do not exclusively, but at least partly, enrol patients with non-ischaemic CS.30 These trials, and others, which will hopefully follow, will help to define the role of MCS in treatment of non-ischaemic CS in the future.

Higher risk of safety events with mechanical circulatory support in non-ischaemic cardiogenic shock

One major pitfall of MCS is the increased risk of complications.8-10, 18 This is plausible, as all available MCS devices require a relatively large bore vessel access and interfere with the patient's blood and coagulation system.5 Also, the higher likelihood of complications is even observed when MCS is used in a more stable situation, e.g. for high-risk percutaneous coronary interventions.31 Correspondingly, complications, such as bleeding complications but also access site-related ischaemia, occurred more frequently in patients treated with MCS. We also observed that especially patients with a low baseline risk of bleeding (e.g. younger patients, those with less severe CS or those on lower doses of catecholamines) seem to be at a disproportionally higher risk of suffering MCS-associated severe bleeding. Overall, this highlights the (most likely) causative relation between MCS use and complications, and stresses the need to reduce such complications, as they are likely to interfere with the haemodynamic benefit of the devices. Optimizing the implantation setting as well as the device management is therefore not only important because it prevents/reduces complications, but also because it positively influences the benefit–risk ratio of the MCS approach. Several measures are available for this purpose, from sonography/angiography-guided device placement to a more sophisticated monitoring of anticoagulation and haemolysis in patients with MCS.32, 33 Additionally, use of MCS should be organized in ‘shock teams’, which can help to reduce the risk of complications by improving the up-front selection of appropriate candidates for MCS treatments.34

Interaction between cardiogenic shock severity and mechanical circulatory support

The higher risk of complications also highlights the need to prioritize MCS use in patients with a presumed greater benefit. In this regard, the subgroup analysis found an association between MCS use and lower mortality risk especially in patients with deteriorating CS. As per the SCAI CS classification, deteriorating CS is defined as disease progression despite conventional treatment (thus distinguishing it from classic CS), but not yet full cardiac collapse (thus distinguishing it from in-extremis CS).1 This could be the ‘sweet spot’ for MCS use, where the benefit from the haemodynamic support might be relatively higher as compared to patients who respond to conventional treatment; but not yet futile as in patients with full cardiac collapse, where multi-organ failure and non-cardiac/non-haemodynamic pathomechanisms become the main drivers of mortality. In the present study, patients with higher SCAI CS class had more severe CS (e.g. higher lactate, lower pH, more frequently presented with prior cardiac arrest), indicating more multi-organ damage, and showed more severe respiratory failure (as indicated by a worse PaO2 to FiO2 ratio), which would support this hypothesis. However, given the potential bias with secondary analyses in general and with the retrospective application of the SCAI CS classification in particular, this needs to be interpreted with much caution and should be further evaluated by prospective trials.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the non-randomized data, so that a causal relation between intervention and outcomes cannot be concluded. This needs to be kept in mind when interpreting the results of this study, especially as the use of MCS in real-world practice is a selective process, where patients with a higher physiological reserve are more likely to be treated with MCS. Although propensity-score matching was performed based on known confounders such as age or lactate to balance the study groups, the impact of unmeasured or unknown confounders, especially the treating physician's assessment of the patient's physiological reserve, cannot be ruled out. Also, variables for the propensity score matching were selected to reflect CS severity, and selecting different variables, such as those reflecting comorbidity burden, which was slightly higher in patients not treated with MCS, might have yielded different results. It would therefore have been preferable to conduct this study in a randomized fashion. However, there was no rationale for such a trial due to the paucity of data on this topic, so that the presented findings should be seen as hypothesis-generating and should be used to inform the conduction of a randomized controlled trial on this topic.

Further limitations relate to the missingness of characteristics beyond those reported, so that the impact of these on the findings were not evaluated; as well as to the missingness of data regarding timing of complications, so that we could not evaluate the association between these and the actual use of the MCS devices (e.g. if complications happened during or after MCS use). Also, the analysis on patients treated with versus without LV unloading is confounded by the primary analysis, which indicated an association between MCS use and lower mortality, as all patients in the LV unloading group were treated with MCS, and only some in the group without LV unloading, so that it should be interpreted with caution and might only be seen as hypothesis-generating. Different baseline definitions for patients treated with versus without MCS were used to capture patients in similar states of CS (e.g. MCS implantation as a marker for clinical deterioration in patients treated with MCS, and intensive care unit/hospital admission as a marker for clinical deterioration in patients not treated with MCS), and changing these definitions might impact the results. Furthermore, it is likely that testing for haemolysis, and potentially also for other complications, was less rigorously performed in patients not treated with MCS, as they are at a much lower risk of suffering from these than patients treated with MCS, which might contribute to underreporting of such events in the control group. Lastly, although the data were derived from multiple hospitals/countries, all hospitals are large tertiary care centres with ample experience in MCS use, which might not only explain the high use of MCS or other patient characteristics (e.g. high prevalence of prior cardiac arrest) in the study cohort, but which also indicates a potential selection bias towards patients treated with (or being evaluated for) MCS, and which limits generalizability.

Conclusion

In this retrospective, multicentre, international, propensity score-matched study of patients with non-ischaemic CS (e.g. caused by severe de-novo or acute-on-chronic heart failure, but not by acute myocardial infarction), MCS use was associated with a 24% relative risk reduction in 30-day mortality, but also with more complications, especially bleeding.

Given the high mortality risk of non-ischaemic CS and the lack of effective treatments, this observational study should be seen as a strong call for a randomized controlled trial of MCS in non-ischaemic CS, potentially unravelling the first effective treatment of this disease.

Acknowledgement

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest: B.S. reports speaker fees from Abiomed and AstraZeneca, outside of the submitted work. B.N.B. reports honoraria from Siemens Healthineers, outside of the submitted work. S.B. reports grants and personal fees from Abbott Diagnostics, Bayer, Siemens, Thermo Fisher, grants from Singulex, personal fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Medtronic, Pfizer, Roche, Siemens Diagnostics, Novartis, outside of the submitted work. D.E. reports speaker fees from Abiomed, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, outside of the submitted work. P.H. reports travel compensation from Abiomed, outside of the submitted work. P.K. reports research support for basic, translational, and clinical research projects from European Union, British Heart Foundation, Leducq Foundation, Medical Research Council (UK) and German Centre for Cardiovascular Research, from several drug and device companies active in atrial fibrillation, and has received honoraria from several such companies in the past, but not in the last 3 years. He is listed as inventor on two patents held by University of Birmingham (Atrial Fibrillation Therapy WO 2015140571, Markers for Atrial Fibrillation WO 2016012783; unrelated to the submitted work). S.K. reports research support from Cytosorbents and Daiichi Sankyo. He also received lecture fees from Astra, Bard, Baxter, Biotest, Cytosorbents, Daiichi Sankyo, Fresenius Medical Care, Gilead, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Pfizer, Philips and Zoll. He received consultant fees from Fresenius, Gilead, MSD and Pfizer, outside of the submitted work. P.L. reports speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, EdwardsLifesciences, Medtronic and Pfizer outside the submitted work. N.M. reports lecture fees Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb and grant research from Getinge Global USA and Italfarmaco, outside of the submitted work. M.O. reports speaker honoraria from Abbott Medical, AstraZeneca, Abiomed, Bayer vital, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CytoSorbents, Daiichi Sankyo Deutschland, Edwards Lifesciences Services, Sedana Medical, outside of the submitted work. A.P. reports an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Vascular, outside of the submitted work. T.R. reports speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Daiichy, Bayer, Novartis, Abiomed outside the submitted work. D.W. reports speaker fees from Abiomed, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Berlin-Chemie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis and Medtronic, outside of the submitted work. All other authors have nothing to disclose.