Association of baseline eGFR and incident heart failure on patients receiving intensive blood pressure treatment

Li Haonan, He Qiaorui and Zhu Wenqing contributed equally to this article.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01206062.

Abstract

Aims

We aim to elucidate the association of baseline eGFR and incident heart failure on patients receiving intensive BP treatment.

Methods and results

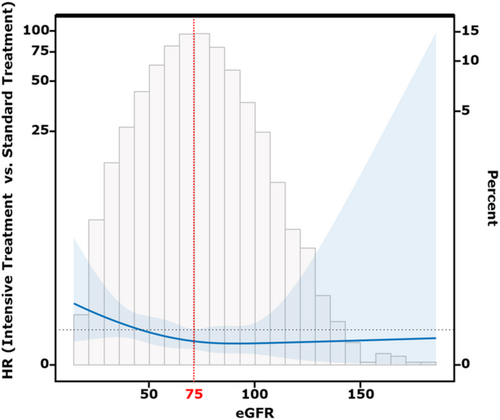

A post hoc analysis was conducted on the SPRINT database. Multivariab le Cox regression and interaction restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis were performed to investigate the interaction between baseline eGFR and intensive BP control on heart failure prevention. The primary endpoint focused on incident heart failure. The study cohort comprised 8369 adults with a mean [SD] age of 68 [59–77] years, including 2940 women (35.1%). Over a median [IQR] follow-up period of 3.9 [2.0–5.0] years, 183 heart failure events were recorded. A significant interaction was observed between baseline eGFR and treatment groups in terms of heart failure prevention (Interaction P = 0.012). The risk of heart failure showed a sharp slope until eGFR = 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 and then became flat by an interaction RCS. Intensive BP treatment did not exhibit a preventive effect on heart failure (HR (95% CI) = 1.03 (0.82–1.52)) when baseline eGFR was 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 or lower. Conversely, when baseline eGFR was higher than 75 mL/min/1.73 m2, a reduced risk of heart failure was observed (HR (95% CI) = 0.65 (0.41–0.98)). Intensive BP control did not increase the incident long-term dialysis regardless of baseline eGFR but was associated with a higher risk of eGFR reduction.

Conclusions

Among nondiabetic hypertensive patients, baseline eGFR serves as a crucial indicator for assessing the risk reduction potential of intensive BP control in heart failure prevention, with 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 appearing as a suitable cut-off value.

Introduction

Heart failure is a common and serious complication in patients with hypertension, which can lead to adverse cardiovascular outcomes.1 Previous studies have shown that intensive blood pressure control can reduce the incidence of heart failure in hypertensive patients.2-4 However, existing research has also demonstrated that intensive blood pressure control may result in worsening renal function, particularly evidenced by a significant decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), especially in patients without pre-existing chronic kidney disease.2, 5 During the initiation of intensive blood pressure treatment, fluctuations in blood pressure can induce hemodynamic changes within the kidney. The kidney can maintain constant renal blood flow through myogenic reflexes and tubuloglomerular feedback mechanisms.6 However, this self-regulation has a certain limit.7 Excessive blood pressure reduction may lower renal perfusion pressure beyond the self-regulation range, resulting in acute renal dysfunction. A decline in eGFR of 5%–20% may reflect adjustments in renal hemodynamics, with potential recovery of eGFR as blood pressure stabilizes. In contrast, an eGFR decline of ≥20% may reflect hemodynamic dysregulation, which may lead to irreversible renal function deterioration.8, 9 Both the SPRINT trial and the STEP trial revealed that the proportion of patients with a ≥30% decline in eGFR was significantly higher in the intensive treatment group compared to the standard treatment group. For patients with high baseline eGFR levels, this may have less of an effect, but for patients with previous low eGFR levels, this may lead to deterioration of renal function. Moreover, the effects of long-term intensive treatment on renal function may also persist over the long term. Renal dysfunction itself is a significant factor leading to the occurrence of heart failure.10, 11 The renal function deterioration can result in reduced excretion of salt and water, leading to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Concurrently, increased sympathetic nervous activity further can further enhance RAAS-mediated fluid overload and increase systemic vasoconstriction. These compensatory mechanisms contribute to increased cardiac fibrogenesis, thereby accelerating the progression of heart failure.12

Therefore, it is important to understand whether the baseline eGFR levels prior to intensive blood pressure control could influence its protective effect against incident heart failure. Although there have been numerous studies investigating the relationship between eGFR and intensive blood pressure control,9, 13-17 previous research has often categorized patients into different groups based on eGFR values to compare the differences in the effects of intensive blood pressure control among these groups.18, 19 However, eGFR is a continuous variable, and by exploring its role as a continuous variable in the context of intensive blood pressure control, we may be able to more accurately distinguish which patients are likely to benefit from intensive blood pressure control.

Hence, this study aims to analyse eGFR as a continuous variable and explore whether there is an interaction between different eGFR levels and the impact of intensive blood pressure control on incident heart failure. Additionally, we will try to identify a specific eGFR cut-off value that can differentiate the effectiveness of intensive blood pressure control. This research endeavour seeks to provide clinical evidence for better targeting and identifying individuals who would benefit the most from intensive blood pressure control in the future.

Methods

This study was a post hoc analysis of participants in the SPRINT20 (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial). Data were obtained from the National Institutes of Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center via an approved proposal.

Study population

A detailed description of the SPRINT design and results has been reported.2 In brief, the SPRINT was an open-label, randomized controlled trial that compared the therapeutic benefits of intensive SBP therapy targeting a goal of <120 mmHg with standard SBP therapy targeting a goal of <140 mmHg. The SPRINT trial included 9361 adults with hypertension and increased cardiovascular risk and excluded those with diabetes or prior stroke. The institutional review board of each site from each trial approved the protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Estimation of glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculation

SPRINT study used a 4-variable MDRD equation to calculate eGFR. The 4-variable equation derived using the data obtained from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study is the most commonly used method to calculate the eGFR among the clinics in the United States. This MDRD equation is as follows:

eGFR (in mL/min/1.73 m2) = 186.3 × (serum creatinine in mg/dL) − 1.154 × (age in years) − 0.203 × 1.212 (if black) × 0.742 (if female).

Follow-up and study outcome

Participants were followed up from baseline until the first event occurred or the end of follow-up. The primary outcome of interest for this study was incidence of heart failure, which defined as the first occurrence of hospitalization, or emergency department visit requiring treatment with infusion therapy, for a clinical syndrome that presents with multiple signs and symptoms consistent with cardiac decompensation/inadequate cardiac pump function.2 This outcome includes definite or possible acute decompensation, including heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction as well as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and they were not further subdivided. Secondary outcomes were cardiovascular death (CVD death), nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), nonfatal stroke and all-cause death. Detailed definition of outcomes has been described previously2. The renal outcomes included development of end-stage renal failure which need long-term dialysis, eGFR reduction (defined as ≥50% reduction in estimated GFR in participants with a baseline eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and ≥30% reduction in estimated GFR to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in participants with a baseline eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and the composite of the above two outcomes. Relevant data were gathered according to a standard protocol, and events were adjudicated by an independent committee blinded to treatment allocation.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD, nonnormally distributed continuous data as median (interquartile range), and categorical data as numbers (percentage). Continuous variable distribution was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test for normality.

To evaluate if there is a differential effect of eGFR and intensive blood pressure treatment on incident heart failure, we performed an interaction of eGFR (as a continuous variable) and blood pressure treatment group in the multivariable Cox model. Factors that could potentially affect the incidence of heart failure were adjusted as covariates in the Cox model. These included demographics (age, gender, race and body mass index), clinical risk factors [presence of cardiovascular disease before randomization, total cholesterol at baseline, smoking status, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi) treatment, baseline systolic blood pressure and eGFR]. The proportional hazards assumption had been verified using Schoenfeld residual plots. Splines were produced by using the estimated HR of a Cox model with a baseline eGFR × treatment group interaction term through the R package interactionRCS (R Project for Statistical Computing).21 The interaction RCS was performed to initially figure out the potential cut-off value of eGFR for stratification the effect of intensive blood pressure control. We selected the point near the maximum change in slope as the potential cutoff value since the Interaction RCS curve exhibited an L-shaped pattern (Figure 1). The interaction RCS was also adjusted for aforementioned covariates. Then, we separated the participants into two groups by the eGFR cut-off value and performed multivariable Cox analysis to verify the predictive value of the cut-off value for the effect of intensive blood pressure treatment. All analyses were conducted using R 4.0.1 (version 4.2.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) software. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value <0.05.

Results

This study is a post hoc analysis of the SPRINT study. In the present study, we excluded 150 participants with missing value of baseline data, 205 without completed baseline cardiovascular risk record and 637 with less than 3 BP records during follow-up period. Finally, a total of 8369 participants were eligible for this study (Figure S1). There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of baseline demographics. There were also no significant differences in past history of cardiovascular disease, baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and baseline eGFR (Table 1). On a median follow-up of 3.9 years (IQR: 2.0–5.0 years), there were 183 (2.2%) incident heart failure events. In the multivariable Cox regression model with incident heart failure as the endpoint, we found that intensive blood pressure treatment significantly reduced the incidence of heart failure in the overall population (HR: 0.31(0.12–0.81), Table 2), but there was an interaction between baseline eGFR and treatment group (interaction P = 0.012, Table 2). This suggested that the effect of intensive blood pressure treatment may be influenced by baseline eGFR. Subsequently, through interaction RCS curves, we found that the impact of intensive blood pressure management was less pronounced at lower baseline eGFR levels, but gradually became more apparent as eGFR levels rose. We then identified the intersection point of HR with the point near the maximum change in slope in the graph (eGFR ≈ 75 mL/min/1.73 m2) as the cut-off value for eGFR since the RCS curve was a L-shape pattern (Figure 1) and divided participants into two groups. The baseline demographics according to different eGFR groups were showed in Table S1. There were no significant differences in most parameters between treatment groups in two eGFR groups. We found that intensive blood pressure treatment significantly reduced the incidence of heart failure in patients with eGFR > 75 [HR (95% CI) = 0.65 (0.41–0.98)], while there was no significant benefit in patients with eGFR ≤ 75 (Table 3). Similar result was also observed in the outcomes of cardiovascular death and stroke, indicating that baseline eGFR = 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 might be a potential cut-off value for determining whether intensive blood pressure treatment can reduce the incidence of heart failure.

| Characteristic | Treatment group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, N = 8369a | Standard treatment, N = 4167a | Intensive treatment, N = 4202a | |

| Age | 68 ± 9 | 68 ± 9 | 68 ± 9 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 5429 (64.9%) | 2724 (65.4%) | 2705 (64.4%) |

| Female | 2940 (35.1%) | 1443 (34.6%) | 1497 (35.6%) |

| Race | |||

| Nonblack | 5823 (69.6%) | 2880 (69.1%) | 2943 (70.0%) |

| Black | 2546 (30.4%) | 1287 (30.9%) | 1259 (30.0%) |

| BMI | 29.9 ± 5.7 | 29.9 ± 5.7 | 29.9 ± 5.8 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoker | 3678 (43.9%) | 1826 (43.8%) | 1852 (44.1%) |

| Ex-smoker | 3621 (43.3%) | 1823 (43.7%) | 1798 (42.8%) |

| Current smoker | 1070 (12.8%) | 518 (12.4%) | 552 (13.1%) |

| Previous CVD | |||

| No | 6684 (79.9%) | 3334 (80.0%) | 3350 (79.7%) |

| Yes | 1685 (20.1%) | 833 (20.0%) | 852 (20.3%) |

| Previous CKD | |||

| No | 5997 (71.7%) | 2993 (71.8%) | 3004 (71.5%) |

| Yes | 2372 (28.3%) | 1174 (28.2%) | 1198 (28.5%) |

| Baseline SBP (mmHg) | 140 ± 16 | 140 ± 15 | 140 ± 16 |

| Baseline DBP (mmHg) | 78 ± 12 | 78 ± 12 | 78 ± 12 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190 ± 41 | 190 ± 41 | 190 ± 41 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 112 ± 35 | 113 ± 34 | 112 ± 36 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 99 ± 14 | 99 ± 13 | 99 ± 14 |

| uACR (mg/g) | 41 ± 165 | 40 ± 151 | 43 ± 178 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 72 ± 20 | 72 ± 20 | 72 ± 21 |

- Note: No statistically significant difference between groups in any patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | 0.41(0.22–0.91) | 0.025 |

| Baseline eGFR (per SD change) | 0.81(0.61–0.90) | 0.048 |

| eGFR (per SD change) × Treatment (interaction) | 0.62(0.45–0.89) | 0.012 |

- Note: Model was adjusted for treatment group, age, gender, race, body mass index, eGFR, uACR, smoking status, total cholesterol, history of CVD, RAASi treatment and systolic blood pressure at baseline.

| Events | Strata | Standard treatmenta | Intensive treatmenta |

HR (95% CI) intensive vs. standard |

P value |

Interaction eGFR × Treatment group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | eGFR ≤ 75 (n = 4791) | 63/2411 (2.6) | 70/2404 (2.9) | 1.03 (0.82–1.52) | 0.959 | 0.021 |

| eGFR > 75 (n = 3530) | 32/1756 (1.8) | 18/1798 (1.0) | 0.65 (0.41–0.98) | 0.045 | ||

| All-cause death | eGFR ≤ 75 (n = 4797) | 154/2411 (6.4) | 144/2404 (6.0) | 0.91 (0.73–1.13) | 0.352 | 0.075 |

| eGFR > 75 (n = 3535) | 70/1756 (4.0) | 50/1798 (2.8) | 0.75 (0.51–1.03) | 0.067 | ||

| CVD death | eGFR ≤ 75 (n = 4785) | 47/2411 (1.9) | 39/2404 (1.6) | 0.81 (0.54–1.25) | 0.298 | 0.201 |

| eGFR > 75 (n = 3532) | 22/1756 (1.3) | 10/1798 (0.5) | 0.48 (0.25–0.99) | 0.048 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | eGFR ≤ 75 (n = 4803) | 96/2411 (4.0) | 64/2404 (2.7) | 0.67 (0.48–0.91) | 0.012 | 0.276 |

| eGFR > 75 (n = 3532) | 46/1756 (2.6) | 28/1798 (1.6) | 0.59 (0.39–0.92) | 0.031 | ||

| Stroke | eGFR ≤ 75 (n = 4789) | 45/2411 (1.9) | 48/2404 (2.0) | 1.07 (0.73–1.61) | 0.825 | 0.101 |

| eGFR > 75 (n = 3531) | 33/1756 (1.9) | 19/1798 (1.1) | 0.56 (0.33–0.96) | 0.034 |

- Note: Model was adjusted for treatment group, age, gender, race, body mass index, eGFR, Smoking status, total cholesterol, history of CVD, RAASi treatment and systolic blood pressure at baseline.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio.

- a No. of events/total no. (%).

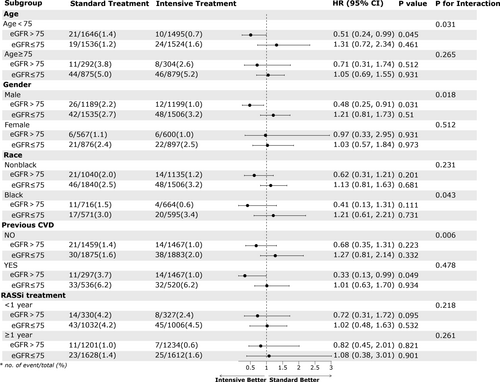

Furthermore, we conducted multivariable Cox regression analysis to assess the impact of intensive blood pressure treatment on renal outcomes in different groups. As seen in Table 4, we observed that intensive blood pressure treatment did not increase the incidence of long-term haemodialysis, regardless of the value of eGFR. But it significantly increased the incidence of eGFR reduction, which was consistent with the result from original SPRINT study. As the calculation formula for eGFR is age-related, we further conducted Cox regression analysis in different age subgroups and found a similar trend in the age subgroups. In other subgroups, except for the female subgroup, the results were consistent with the main results trend (Figure 2). This once again validated the cut-off value of 75 for baseline eGFR in assessing the effectiveness of intensive blood pressure treatment in reducing the incidence of heart failure.

| Events | Strata | Standard treatmenta | Intensive treatmenta |

HR (95% CI) intensive vs. standard |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term dialysis | eGFR ≤ 75 (n = 4634) | 18/2411 (0.7) | 15/2404 (0.6) | 0.81 (0.42–1.58) | 0.51 |

| eGFR > 75 (n = 3372) | 10/1756 (0.6) | 8/1798 (0.4) | 0.83 (0.35–2.13) | 0.69 | |

| eGFR reductionb | eGFR ≤ 75 (n = 4807) | 39/2411 (1.6) | 81/2404 (3.4) | 2.13 (1.44–3.1) | <0.001 |

| eGFR > 75 (n = 3553) | 24/1756 (1.4) | 90/1798 (5.0) | 4.08 (2.78–6.92) | <0.001 | |

| Composite renal outcomesc | eGFR ≤ 75 (n = 4807) | 57/2411 (2.4) | 96/2404 (4.0) | 1.95 (1.35–2.89) | 0.001 |

| eGFR > 75 (n = 3553) | 34/1756 (1.9) | 98/1798 (5.5) | 4.62 (2.81–7.42) | <0.001 |

- Note: Model was adjusted for treatment group, age, gender, race, body mass index, eGFR, Smoking status, total cholesterol, history of CVD, RAASi treatment and systolic blood pressure at baseline.

- a No. of events/total no. (%).

- b eGFR Reduction was defined as ≥50% reduction in estimated GFR in eGFR < 60 group and ≥30% reduction in estimated GFR to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in eGFR ≥ 60.

- c Composite renal outcomes included outcomes of long-term dialysis and eGFR reduction.

Finally, after considering numerous studies on the effects of intense blood pressure treatment in CKD patients (defined as eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2),22 we grouped patients based on their eGFR (eGFR>75, 60–75, <60) and conducted subgroup Cox regression analysis. Our analysis showed that among hypertensive patients with eGFR 60–75, the protective effect of intense treatment against heart failure was diminished [HR (95% CI) = 1.18 (0.56, 2.47), Figure S2]. This suggests uncertainty in using intensive treatment to prevent heart failure when eGFR ≤ 75 mL/min/1.73 m2. In the future, well-designed studies are needed to confirm this proposal.

Discussion

Intensive blood pressure control is a crucial strategy in the management of hypertension to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including heart failure.3, 23-25 Understanding how baseline eGFR influences the effectiveness of intensive blood pressure control in preventing heart failure is essential for optimizing treatment strategies for hypertensive patients.

The findings of the study highlighted significant differences in the preventive effects of intensive blood pressure control on heart failure incidence based on baseline eGFR levels. Specifically, the study discovered that when eGFR was 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 or lower, the preventive effect of intensive blood pressure control on heart failure began to diminish. Importantly, this trend was consistent across different subgroups within the study population, indicating the importance of considering baseline eGFR as a critical factor when developing hypertension treatment strategies.

Previous research has demonstrated that intensive blood pressure control can significantly reduce the risk of heart failure incidence in nondiabetic hypertensive patients as a whole.26, 27 However, several studies have also indicated that intensive blood pressure control may lead to a notable decrease in eGFR,14, 19, 28 which is a crucial factor contributing to heart failure.29 A randomized controlled trial conducted on the chronic kidney disease (CKD) subgroup (defined as eGFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) found that intensive blood pressure control did not lower the incidence of heart failure significantly but may increase the proportion of mild eGFR reduction (eGFR decrease of 30 mL/min/1.73 m2).30 Therefore, it is reasonable that for some patients with mildly reduced eGFR, the benefits of intensive antihypertensive treatment may be diluted by the risk of further eGFR decline, thus resulting in the failure of intensive antihypertensive treatment to reduce the risk of heart failure occurrence. Furthermore, eGFR is a continuous variable, and previous cut-off values of eGFR used to define chronic kidney disease (CKD) did not take into account the factor of intensive antihypertensive treatment.31 Therefore, in the present study, eGFR was analysed as a continuous variable, resulting in different cut-off values. In this study, we selected the cutoff value for eGFR using the interaction RCS. Observing the Spline pattern, it was evident that when eGFR was low, the protective effect of intensive treatment on heart failure was not significant (HR > 1). However, as eGFR increased, the effect of intensive treatment gradually became apparent, resulting in an overall L-shaped curve. Therefore, we initially attempted to set the cutoff value at the eGFR corresponding to HR = 1 (≈50 mL/min/1.73 m2). However, upon performing multivariate Cox regression analysis, we found that this cutoff value did not effectively distinguish the effect of intensive treatment (Table S2). Subsequently, we selected the point with the maximum change in slope (≈75 mL/min/1.73 m2) and discovered that it could better distinguish the efficacy of intensive blood pressure-lowering therapy. We found that intensive BP treatment only benefit participants with a baseline eGFR > 75 mL/min/1.73 m2, indicating a different threshold than the commonly used 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Further subgroup analysis dividing participants into three groups based on eGFR levels reinforced the validity of the proposed threshold, showing that the preventive effect of intensive blood pressure control on heart failure was lost in the group with eGFR between 60 and 75 mL/min/1.73 m2. These findings underscore the impact of renal function on the effectiveness of intensive blood pressure control and suggest that even mild impairment in kidney function (eGFR between 60 and 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 representing stage 2 CKD27) could attenuate the benefits of intensive blood pressure control on incident heart failure.

Moreover, considering that eGFR is based on age-calculated predicted values, subgroup analyses based on age categories were conducted, demonstrating consistent results across different age groups. These results indicated that the cut-off value may be suitable for patients in both middle-or older- age population.

Overall, this study sheds light on the intricate relationship between baseline eGFR and the effectiveness of intensive blood pressure control in preventing heart failure. Further research is warranted to explore these findings and develop nuanced approaches for identifying individuals who would benefit most from intensive blood pressure control interventions.

Study limitations

It is important to consider the limitations of the study when interpreting the results. Firstly, the study was a post hoc analysis based on data from the SPRINT study, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to all hypertensive patients, such as those with hypertension and diabetes or younger individuals. Secondly, the complexity of factors contributing to heart failure incidence means that potential confounders could impact the results, and these were not fully accounted for.

Conclusions

For nondiabetic hypertensive individuals, the study highlighted a significant interaction between baseline eGFR levels and the effectiveness of intensive blood pressure control in preventing heart failure. Individuals with eGFR less than 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 may not derive the full benefits of intensive blood pressure control in reducing the incidence of heart failure. These findings emphasize the importance of considering eGFR as a key factor in tailoring hypertension treatment strategies for optimal clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the SPRINT study for providing important clinical data. We thank the staffs of the SPRINT study for their contributions to data collection.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Youth Talent Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2022YQ023), Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Clinical Research Project (Youth, 20214Y0152), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82170388 and 82370300), Shanghai Technology Research Leader Program (21XD1434700), the Cardiac rehabilitation fund by the International Medical Exchange Foundation (Z-2019-42-1908-3) and Grant for the Construction of Innovative Flagship Hospital for Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine (No. ZY(2021–2023)-0205–05).

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

Patient Consent Statement

This is a post hoc analysis of the SPRINT study.