Abnormal lineage differentiation of peri-implantation aneuploid embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing

Xueyao Chen, Hanwen Yu, Yu Yin, Bing Cai and Gaohui Shi contributed equally to this work.

Dear Editor,

Early pregnancy loss is often caused by embryonic aneuploidy.1, 2 However, the developmental process of aneuploid embryos remains largely unexplored. In this study, we delineated the developmental pattern of aneuploid embryos at the peri-implantation stage through 3D in vitro culture. A gain of chromosome 16 caused the premature development of trophoblasts, while a loss of chromosome 16 led to a blockage in trophoblast differentiation. We found that the CREBBP gene, located on the chr16, regulates the aberrant trophoblast development of monosomy 16 (M16) and trisomy 16 (T16) through a dosage effect, which was further validated in blastoids and TSCs (trophoblast stem cells) models. These findings provide insights into exploration of embryonic defects leading to repeated implantation failure or pregnancy loss.

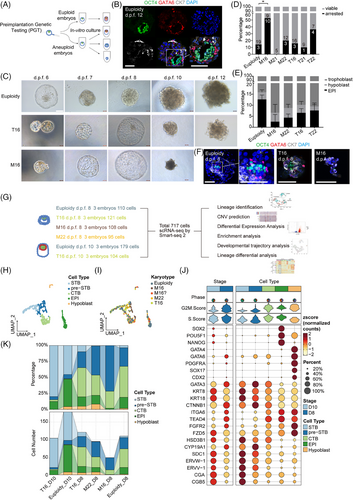

Donated blastocysts were cultured until 12 days post-fertilization (d.p.f. 12) by an in vitro 3D system established by Xiang et al.3 (Figure 1A). In euploid embryos, three embryonic lineages could be identified by specific lineage markers (Figure 1B, Note S1). Aneuploid embryos were significantly smaller in size and exhibited delayed development (Figure 1C). M16 embryos were significantly more likely to arrest before d.p.f.10 (52.6%, n = 10/19) than euploid embryos were (13.6%, n = 3/22, p = .017, Figure 1D). By immunofluorescence, aneuploid embryos exhibited abnormal morphology and poor epiblast (EPI) development (Figure 1E,F). In particular, M16 exhibited the lowest proportion of EPI cells, with only five EPI cells identified across all M16 embryos (n = 11). Few hCGB (+) STB cells (syncytiotrophoblast) were observed in the monosomy embryos, indicating that cell differentiation into STBs was restricted (Figure S1a and 3D,E).

ScRNA-seq analysis of 18 embryos at d.p.f. 8–10 was conducted for characterization of peri-implantation embryo development (Figure 1G, Table S1). Following quality control (Figure S1b), 717 single cells with 40,874 genes (including non-coding genes) were used for subsequent analyses. Seurat was employed for dimensionality reduction and unsupervised clustering analysis. Single cells were annotated into five cell types corresponding to lineage marker expression features (Figure 1H–J, Figure S1c). The UMAP plot showed that M16 embryos contained only trophoblast cells with abnormal distribution (Figure 1I). The EPI cell count was lower in aneuploid embryos than in euploid embryos, with M16 embryos exhibiting the fewest EPI cells (Figure 1K). Regarding the trophoblast lineage, T16 embryos contained more STB cells than euploid embryos, whereas M16 embryos had nearly none. M16 and M22 embryos had a greater abundance of pre-STB cells (Figure 1K).

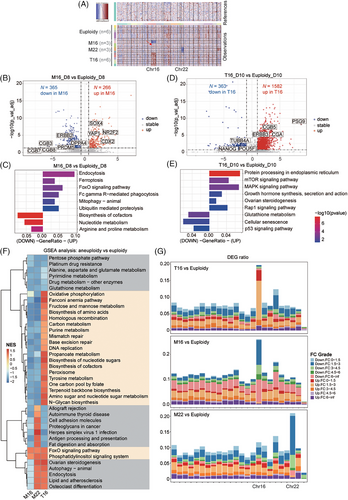

For global transcriptomic analysis, M16 and M22 embryos showed a halved copy number variation (CNV) on Chr 16 or 22, while T16 embryos showed a 1.5-fold CNV increase on Chr 16 (Figure 2A); their inferred CNV levels predicted by R package inferCNV were consistent with the dosage levels of the aneuploid chromosomes (Note S2). Subsequently, we explored the transcriptional characteristics of the whole aneuploid embryos (Table S2 and S3). M16 embryos showed upregulation of cell death-related pathways, including endocytosis, ferroptosis, FoxO signalling and FcγR-mediated phagocytosis pathways. The downregulated genes were enriched in biological metabolism (Figure 2B,C). These findings suggested that M16 embryos had reduced metabolic capacity and initiated apoptosis at the peri-implantation stage. T16 embryos at d.p.f. 10, showed upregulation of pathways related to protein processing, hormone synthesis and steroidogenesis (Figure 2D,E). GSEA analysis (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) identified differential pathway enrichment patterns among distinct karyotypes (Figure 2F, Note S3). DEG distribution across chromosomes showed that the highest number of DEGs in aneuploid embryos was located on the aneuploid chromosomes, suggesting that the dosage effect predominantly affected the transcriptome (Figure 2G, Note S4).

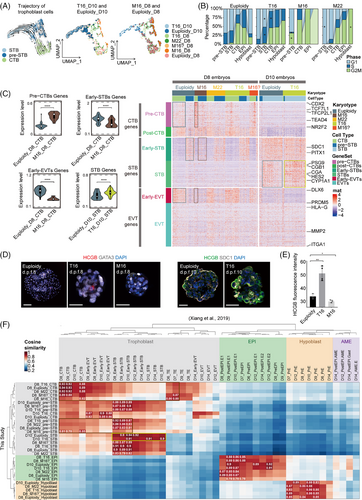

Trophoblast development significantly influenced embryo implantation. To explore trophoblast development in aneuploid embryos, we extracted all trophoblast cells from the scRNA dataset for analysis. RNA velocity-based developmental trajectory analysis suggested that d.p.f. 10 T16 trophoblast cells were more differentiated, whereas M16 trophoblast cells remained undifferentiated (Figure 3A). An increased proportion of cells in the G2/M phase was observed within M16 trophoblasts. Conversely, a greater proportion of T16 trophoblast cells in the G1 phase indicated reduced proliferation (Figure 3B). Next, we examined the expression profiles of specific gene sets highly relevant to trophoblast subtype differentiation3 (Figure 3C). In M16 embryos, CTB (cytotrophoblast)-related genes (including CDX2, NR2F2, SOX4 and TFCP2L) were upregulated, while STB-related genes (including CGA, CGB, PSG and ERVV) and EVT (extravillous trophoblast)-related genes (including HLA-G, ITGA1, DLX6 and PRDM5) were downregulated (Figure 3C, Figure S3a,b, Table S4). The expression of STB-related genes generally increased at d.p.f. 8–10 in both euploid and aneuploid trophoblasts, indicating that physiological STB differentiation occurred during this period. Under this condition, STB-related genes were upregulated in d.p.f. 8 T16 trophoblasts, and the upregulation became more prominent in d.p.f. 10 T16 trophoblasts (Figure 3C). The expression of STB regulatory genes (TBX3, CREB1 and SDC1) did not significantly differ at 8 d.p.f. but increased significantly in T16 embryos at 10 d.p.f. (Figure S3c). By immunofluorescence, we determined that T16 embryos expressed significantly higher HCGB at 8–10 d.p.f. than euploid embryos (Figure 3D,E). Conversely, HCGB (+) cells were barely detected in M16 embryos. The Wnt signalling pathway was predominantly downregulated in T16 trophoblast but upregulated in M16 CTB and pre-STB cells (Figure S4, Note S5, Table S5). Integrating our scRNA-seq data with the published dataset,3 we validated that the trophoblast of the M16 embryo was in a stage of differentiation block, whereas the trophoblast of the T16 embryo prematurely over-differentiated into the STB lineage (Figure 3F, Figure S3d, Note S6).

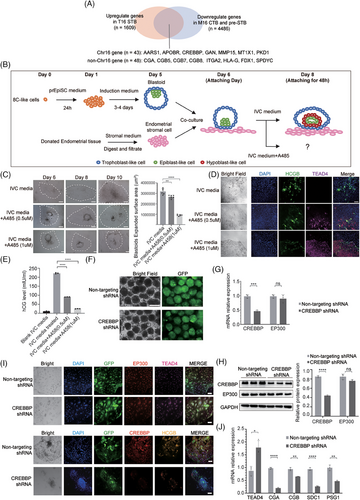

To identify key genes regulating lineage differentiation in Chr16 aneuploid embryos, we screened for DEGs that met three criteria: upregulated in T16 STB, downregulated in M16 CTB or pre-STB and located on Chr16. We identified 43 genes including AARS1, APOBR, CREBBP, GAN, etc. (Figure 4A, Table S6). Among them, CREBBP has been reported to be associated with trophoblast development.4, 5 CREBBP shares structural and functional similarities with EP300 and KAT8, both of which were reported to be involved in trophoblast differentiation.4, 6, 7 SCENIC-based TF regulon analysis identified ELF3, CEBPA, CEBPB and FOXO1 as the most transcriptionally active regulators in aneuploid embryos (Figure S5, Table S7, Note S7), all of which are reported to be associated with CREBBP.8, 9 Based on the analysis, we hypothesized that CREBBP may be responsible for the differences in trophoblast development between M16 and T16 embryos.

We used an in vitro blastoid model to elucidate the impact of CREBBP on trophoblast differentiation and implantation (Figure 4B, Figure S6a,b). After A485 (a CREBBP/EP300 inhibitor) was added to the culture system, the expanded surface area of blastoids significantly decreased (Figure 4C), indicating a reduced adhesion capacity of the trophoblast in blastoids. Immunofluorescence revealed a decrease in HCGB expression and an increase in TEAD4 expression following A485 treatment (Figure 4D). Furthermore, there was a significant decrease in the level of hCG secreted in the supernatant of blastoids following A485 treatment (Figure 4E). We also confirmed the above conclusion in TSCs (Figure S6c–e, Note S8). Our results implied that CREBBP/EP300 suppression preserves the CTB state and inhibits differentiation into the STB in TSCs and blastoids, consistent with the trophoblast phenotype observed in M16 embryos.

To rule out the influence of EP300, we specifically investigated the role of CREBBP in trophoblast differentiation. By introducing CREBBP shRNA-carrying lentiviruses into the blastoids, we effectively reduced CREBBP expression without compensation of EP300 (Figure 4F–H). Following CREBBP knockdown, we cultured the blastoids in vitro until day 10. The blastoids exhibited a gene expression pattern similar to M16 with upregulation of TEAD4, and downregulation of hCG, CGA, SDC1 and PSG1, indicating a block in differentiation from CTB to STB (Figure 4I,J). In this unique CREBBP knockdown model with no compensatory upregulation of EP300, we demonstrated that CREBBP plays a crucial role in maintaining STB differentiation.

In conclusion, our study confirmed that aneuploid embryos exhibited diverse developmental abilities at the peri-implantation stage. We discovered that loss of chr16 can result in abnormal development of the EPI, whereas loss of M22 did not result in this defect. A gain of chr16 caused the premature development of trophoblasts, while a loss of chr16 led to a decrease in trophoblast differentiation. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CREBBP is one of the dosage genes affecting STB differentiation at the peri-implantation stage. CREBBP may have potential applications in assessment of embryo developmental competence, which could help optimize PGT strategies and improve implantation success rates. Our study serves as a reference for peri-implantation development, offering valuable insights into the molecular characteristics and transitions occurring during early embryo development. This may lay a foundation for further explorations of embryonic defects leading to repeated implantation failure or pregnancy loss.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yanwen Xu, Tianqing Li and Chenhui Ding initiated the project. Xueyao Chen performed embryo culture, data collection and wrote the manuscript. Hanwen Yu and Yin Yu performed scRNA-seq data analysis and wrote the manuscript. Bing Cai performed the blastoids-related experiments. Gaohui Shi performed the TSC-related experiments. Yan Xu collected and analysed the PGT data. Lujuan Rong performed embryo staining and photo processing. Boyan Wang performed the blastoids-related experiments. Canquan Zhou and Jichang Wang provided the guidance and instructions for the project. Chenhui Ding provided clinical samples and technical guidance. Tianqing Li designed and organized the experiments. Yanwen Xu conceived the study and supervised the entire project.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grants from National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC2705503, 2022YFA1103100) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (32130034) and Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (2023A04J2178).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw sequence data of single-cell RNA-sequencing in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive10 in National Genomics Data Center11, China National Center for Bioinformation / Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA-Human: HRA005378) that are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human. The scRNA-seq data of human peri-implantation embryos (for Figure 3D, Figure S3d, ref3) is downloaded from GEO: GSE136447. The custom codes used for the data analyses is now available in our GitHub repository (https://github.com/AIBio/CXY_Aneuploid_scRNA-seq).

This study was approved by the Medicine Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (LS[2022]No.092). Donated embryos were abnormal blastocysts screened by preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) or affected embryos determined by preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders (PGT-M). The informed consent process followed guidelines set by the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) and China’s Ministry of Science and Technology and Ministry of Health. The Medicine Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, evaluated the scientific merit and ethics of this study. The committee fully reviewed embryo donation and use. All donor couples provided a voluntary informed consent for the research use of surplus embryos in the Department of Reproductive Medicine at The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University. No financial compensation was provided. Donor couples were informed that embryos would be used to study human development and donation would not affect their treatment. Culture of all embryos was terminated before d.p.f. 14 to comply with ethical guidelines.