Development of Pseudosacral Cyst Following Surgery for Primary Presacral Neuroendocrine Tumors With Liver Metastasis: A Case Report

Funding: This work was supported by Discipline platform construction fund of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (XKJS202017) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82103162).

Li Jian and Youheng Wang contributed equally to this work.

ABSTRACT

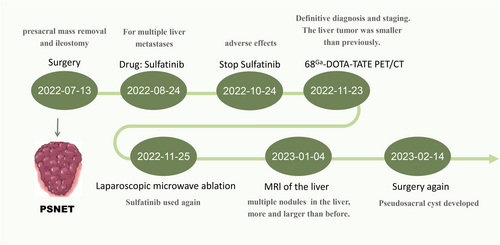

Presacral neuroendocrine tumor (PSNET) is a rare disease that currently lacks a standardized treatment approach. In this report, we present a unique case of PSNET with liver metastasis that progressed into a pseudosacral cyst following complete surgical resection and sulfatinib treatment with radiofrequency ablation. Before undergoing surgical treatment for presacral neuroendocrinology, it is important to consider the potential risks of poor healing of the presacral incision and formation of pseudocysts. These complications may be caused by various factors, including the procedure itself and the use of targeted drugs.

Summary

- A 49-year-old woman presented with hematochezia. MRI revealed a presacral mass with liver metastasis.

- Mass was resected through a transperineal approach and a terminal ileostomy.

- Pathology confirmed a G2 neuroendocrine tumor.

- She received sulfatinib and had radiofrequency ablation of the liver tumors.

- Subsequently she developed an anterior sacral pseudocyst required surgical intervention.

1 Introduction

Presacral neuroendocrine tumor (PSNET) is a rare disease that has been increasing in prevalence, yet there are currently no established diagnostic or treatment protocols [1]. Previous case reports and case studies have focused on the diagnosis of this group of diseases and the prognosis resulting from different treatment modalities, but few articles have focused on post-operative complications. We report a case of presacral neuroendocrine tumor with liver metastasis, which developed a presacral pseudocyst after surgery. In this article, we present a detailed account of the treatment administered to a patient and offer a preliminary analysis of the possible causes of pseudocyst formation. Our objective is to provide a valuable resource for the comprehensive management of similar cases in the future.

2 Case History and Examination

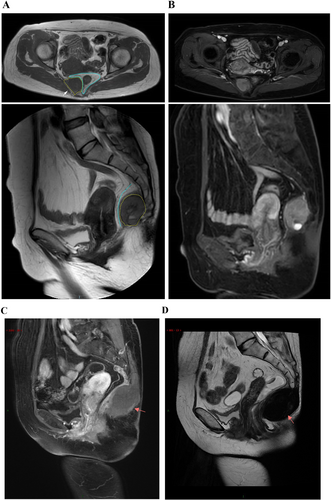

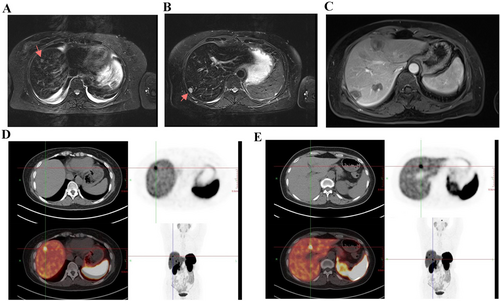

A 49-year-old female patient presented to the clinic for the first time with hemorrhoids and blood in her stool. She had a medical history of cesarean section and uterine fibroids. Laboratory investigations revealed hyperuricemia, with a total bilirubin of 33.1 μmol/L and indirect bilirubin of 28.0 μmol/L. Colonoscopy revealed colonic melanosis and descending colonic polyps. During the examination, a tougher, elevated mass was discovered in the left rectal wall while the patient was in the truncated position. Subsequently, CT and MRI of the pelvis were performed, which revealed a very large mass in the anterior sacral region, adjacent to the rectum (Figure 1). Further examination of the abdomen revealed lesions in the liver as well.

3 Methods

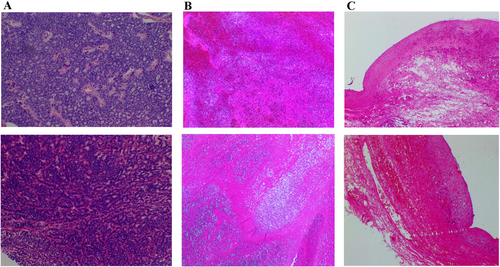

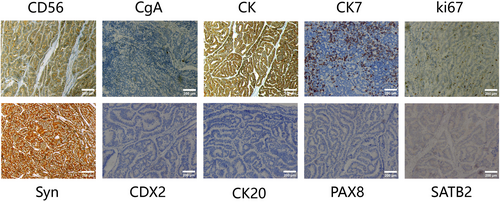

After consultation with a multidisciplinary team, it was concluded that this was a presacral malignancy with concomitant liver metastases. A sacrococcygeal approach was used to remove the presacral mass, which was closely attached to the rectal wall and presacral tissues, and resulted in damage to the rectal plasma membrane. A repair was performed, and a terminal ileostomy was created. There was minimal bleeding in the presacral area, which was controlled with sutures and hemostatic material. Two drains were left in the anterior sacral cavity, and the patient experienced pale red drainage for approximately 2 weeks postoperatively. The patient was anemic and received a blood transfusion after the operation. Post-operative pathology report: The resected pre-sacral lesion specimen revealed a neuroendocrine tumor (NET, G2) measuring approximately 4.5 × 3 × 3 cm without invasion of bone tissue, intravascular tumor thrombus was observed, but no clear nerve invasion was detected (Figure 2). The long-axis and short-axis cut edges showed no evidence of cancer. Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the tumor cells were positive for SYN, CK, CD56, CK7, and CgA. The Ki-67 proliferation index was 3%. However, the markers CK20, CDX2, SATB2, and PAX8 were all negative (Figure 3). After a multidisciplinary assessment, the patient was diagnosed with a presacral primary neuroendocrine tumor with liver metastases. One month after surgery, the patient's anemia and nutritional status improved. Following discussions with the patient and their family, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (sulfatinib, 300 mg daily) was administered.

4 Conclusion and Results

However, after 2 months of oral medication, the patient experienced drug complications, including oronasal bleeding, increased blood pressure, and renal impairment, leading to discontinuation of the drug.

After a month without medication, the patient's symptoms resolved, and they were readmitted for a follow-up examination. MRI and PET-CT (68Ga-DOTA-TATE, 18F-FDG) showed no recurrence of the primary tumor, and the liver metastases had reduced in size. After a comprehensive evaluation, the patient underwent fluoroscopic laparoscopic microwave ablation of the liver tumor (Figure 4).

One month after the second procedure, the patient's liver lesions progressed, and it was believed that long-term discontinuation of medication was the cause. As a result, the patient resumed taking a reduced dose of sulfatinib (200 mg daily) orally. After 1 month of oral medication, the patient developed a subcutaneous bulge below the original surgical wound. An ultrasound at a local hospital suggested fluid accumulation, and an MRI at our hospital confirmed that the liver lesion had not progressed and the possibility of sacroiliac fluid and blood accumulation was considered (Figure 1). The patient underwent surgery again, during which a pseudocyst was discovered in the presacral area. The pseudocyst had encapsulated a large amount of blood clot and dark red bloody fluid. Post-operative pathology indicated that the pseudocyst was encapsulating blood.

The patient was once again taken off oral medication and is currently being monitored for 2 months while the incision gradually heals. As peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) is currently only available through clinical trials in our region, this patient is currently seeking treatment for their condition elsewhere. The complete treatment process for the patient is depicted in Figure 5.

5 Discussion

Patients with presacral neuroendocrine tumors are often asymptomatic because the tumor is typically indolent and patients have usually already developed metastases at the time of diagnosis [2]. In cases of suspected malignancy in presacral masses, we refrained from performing ultrasound-guided aspiration biopsy to determine the nature of the tumor. This was done to avoid the risk of malignant cell dissemination and metastasis, as well as potential infection that may arise from blind puncture or drainage prior to surgery [3-5]. In addition, preoperative MRI is highly specific in detecting the involvement of tumor blood vessels and pelvic sidewalls, making it a valuable tool for diagnosing heterogeneous retrorectal tumors [6]. 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET/CT is a non-invasive tool that can effectively assess tumor heterogeneity, particularly in G2 and G3 NE, and aid in individualized patient management [7], we also adopted this approach postoperatively. The presence of glandular epithelium in the presacral mass is a probable cause of many of these tumors, as there is no apparent source of neuroendocrine cells in the presacral area [8].

Whether the presacral mass is malignant or not, it is highly beneficial for the patient to undergo an en-bloc resection, maximizing the potential for positive outcomes [9-12]. When performed by a highly experienced surgeon, the trans-sacral access method is both safe and effective for patients with presacral tumors located below the sacral 3 level [13]. Presacral tumors are often closely connected to the rectal wall and cannot be distinguished, which leads to some degree of damage to the rectal wall during complete tumor resection. Therefore, it is necessary to avoid post-operative intestinal fistula and presacral infection, and a small intestine or colonostomy is necessary [14, 15]. With the progress of surgical technology, laparoscopic and robot-assisted transabdominal surgery or a combination of abdominal and perineal surgery are also viable options for the treatment of sacral tumors [16-18].

The powerful oral kinase inhibitor sulfatinib showed anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor action by selectively targeting VEGFR (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor), FGFR1 (fibroblast growth factor receptor 1) and CSF1R (colony stimulating factor 1 receptor) [19], and has now completed a phase III clinical trial. It has shown good therapeutic results for advanced non-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [19-21]. The drug was able to hinder the development of the tumor in our situation. Complications associated with sulfatinib include hepatic and renal impairment, hypertension, bleeding, gastrointestinal perforation, and delayed wound healing. Unfortunately, the patient in our report experienced multiple complications, leading to a temporary discontinuation and reduction of the drug. On the other hand, the formation of the patient's presacral pseudocyst may have been caused by several factors, including the use of sulfatinib. Following complete surgical removal of the presacral tumor, the patient's anemia, poor nutritional status, the filling of the wound with hemostatic material and use of sulfatinib contributed to delayed wound healing, resulting in a residual cystic cavity in the presacral area. Continued use of sulfatinib further led to bleeding, allowing the cavity to expand and form a blood-encapsulated pseudocystic cavity. Given the complexities associated with poor incisional healing, as well as the formation of presacral effusion and hematoma following the removal of an anterior sacral mass [22, 23], we believe that the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors should be carefully considered, as they have the potential to worsen these complications.

Local treatments, such as radiofrequency ablation, arterial embolization, and selective internal radiation therapy, are utilized to manage liver metastases by effectively reducing tumor burden and enhancing patients' quality of life [24, 25]. Although our patient received local treatment, there was no targeted drug intervention, resulting in the progression of the liver lesion. In addition, in some large NET centers, many patients with distant metastases have been effectively controlled with PPRT [25-27]. Several authors have reviewed case studies of presacral neuroendocrine tumors, and details can be found in the previous published reviews [24, 25]. We discuss here the possible complications following resection of presacral tumors in a focused manner. We strongly emphasize the importance of selecting a personalized protocol that is suitable for the patient's unique circumstances.

Author Contributions

Li Jian: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Youheng Wang: conceptualization, software, validation, visualization. Yu Hao: formal analysis, investigation, resources, visualization. Wan Songlin: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, validation. Ding Zhao: conceptualization, resources. Qian Qun: data curation, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing – review and editing. Li Daojiang: conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

This article is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82103162), Discipline platform construction fund of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (XKJS202017).

Consent

We have obtained written informed consent from the patient and the patient's family as well as permission to publish the case in the journal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All image data were extracted from the clinical PACS of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University.