An Unusual Case of Girl With Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Later Diagnosed With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Diagnostic Challenges in Pediatric Rheumatology

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

This case report underscores the diagnostic challenges in autoimmune diseases, particularly when initial diagnoses are uncertain. A patient initially diagnosed with juvenile Idiopathic arthritis experienced relapse, revealing systemic lupus erythematosus. This highlights the need for ongoing vigilance and careful consideration of alternative diagnoses, even in patients with seemingly clear initial presentations.

Abbreviations

-

- ACLE

-

- acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

-

- ANA

-

- anti-nuclear antibody

-

- Anti-CCP

-

- anticyclic citrullinated peptide

-

- ASLO

-

- anti-streptolysin O

-

- CCLE

-

- chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

-

- CRP

-

- C-reactive protein

-

- DLE

-

- discoid lupus erythematosus

-

- ESR

-

- erythrocyte sedimentation rate

-

- JIA

-

- juvenile arthritis

-

- JIA

-

- juvenile idiopathic arthritis

-

- MTX

-

- methotrexate

-

- NSAIDs

-

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

-

- RF

-

- rheumatoid factor

-

- SCLE

-

- subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

-

- SJIA

-

- systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis

-

- SLE

-

- systemic lupus erythematosus

-

- TNF-α

-

- tumor necrosis factor alpha

1 Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease with heterogeneous manifestations [1], which vary both among patients and even in the same person through the time [2]. Its incidence varies geographically [1], with the highest prevalence in individuals of African ethnicity [2]. SLE's etiology is multifactorial, involving environmental, genetic, hormonal, and infectious mechanisms [3], explaining the diversity of its treatment approaches [2]. In contrast, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a prevalent rheumatic disease in children, affecting 1–4 per 1000. While primarily affecting joints, JIA can also involve extra-articular organs, potentially leading to severe complications [4, 5]. JIA lacks specific diagnostic laboratory markers [5]. This case highlights the challenges of diagnosis when a patient initially responded well to JIA treatment but later experienced relapse, ultimately leading to the correct diagnosis of SLE.

2 Case Presentation

2.1 Case History

A 14-year-old patient presented with generalized joint pain that started in the hips and then transported to other joints including knees, shoulders, elbows, wrists, and fingers, a history of a fall, and a family history of SLE. Clinical examination showed that there was no hyperthermia or skin symptoms. Blood pressure, heart, and chest auscultation were normal.

2.2 Differential Diagnosis, Investigations, and Treatment

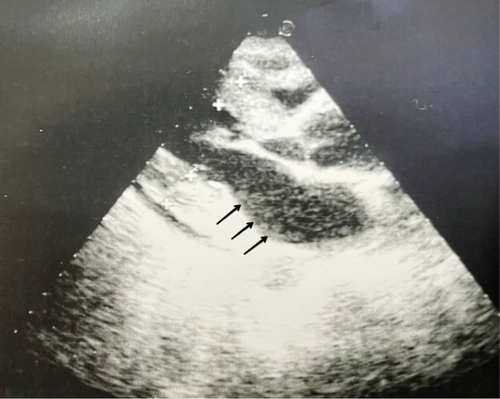

Initial laboratory testing revealed a 9.2 g/dL hemoglobin level value, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of about 122 mm/h, C-reactive protein (CRP) 20.5 mg/dL, and positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) 1/160. Anticyclic citrullinated peptide (Anti-CCP), rheumatoid factor (RF), and anti-streptolysin O (ASLO) were negative. Other laboratory tests of urine sediment, creatinine, and alanine transaminase were within normal ranges. In addition, the laboratory evaluation revealed normal levels of complement C3 and C4, as well as normal platelet counts. A 24-h urine protein measurement indicated a value of 1.8 g. The coombs test was deemed unnecessary due to the absence of clinical signs suggestive of hemolysis. The differential diagnosis and exclusions for generalized joint pain also include: (1) Infectious diseases: the absence of fever, night sweats, or localized signs of infection, lack of exposure history made conditions like brucellosis and tuberculosis unlikely. (2) Hematological malignancies: normal blood counts and lack of systemic symptoms reduced the likelihood of malignancies. (3) Oncological malignancies: the patient's young age and normal examination findings further decreased the probability of solid tumors. (4) Nutritional deficiencies: no signs of malnutrition or dietary deficiencies were reported. (5) Endocrinological diseases: normal blood pressure and absence of systemic symptoms ruled out conditions like Addison's disease. In addition, differential diagnosis included rheumatic fever, juvenile arthritis (polyarticular RF positive JIA, polyarticular RF negative JIA, oligoarticular JIA), and SLE. Financial constraints limited access to confirmatory tests such as imaging or specialized blood work. Thus, we relied on a thorough clinical evaluation for diagnosis. However, the patient's age, clinical presentation, absence of systemic symptoms, and family history strongly support a diagnosis of JIA, with considerations for SLE. Therefore, based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with polyarticular RF negative JIA and treated with methotrexate (7.5 mg/week), folic acid (5 mg/kg/day), and steroids (15 mg/kg/day). The patient initially responded well to the treatment but experienced a recurrence of symptoms after 4 months. Higher doses of the prescribed medications were given with no benefit. Due to persistent joint pain, the patient was transitioned to biological therapy with IL-6 antibodies, which resulted in complete resolution of symptoms. After 6 years, the patient developed new symptoms, including limited wrist joint movement, proteinuria, elevated creatinine, hypertension, and a butterfly or malar rash (Figure 1). A cardiac echocardiogram revealed a pericardial effusion (Figure 2), and a diagnosis of SLE was made. All previous medications were discontinued, and the patient was started on mycophenolic acid (14.2 mg/kg/day), hydroxychloroquine (Blaco 200), an ACE inhibitor (RAMP) a pill/day, and a calcium channel blocker (amyllodipine 5) for SLE.

2.3 Outcome and Follow-Up

The patient showed significant improvement after 1 week of treatment and continues to do well on this regimen.

3 Discussion

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA) is a common and characteristic type of JIA [5]. JIA in children combines all types of chronic arthritis and affects not only the joints but also extra-articular organs, including the eyes, skin, and internal organs, leading to handicap or death [4]. JIA is associated with a fever that lasts for at least 2 weeks, and there must be three successive days of fever and inflammation involving one or more joints with at least one of the following symptoms: erythematous rash, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or serositis [6]. Clinical examination of our patient showed that there was no hyperthermia or skin symptoms. JIA is a rare cause of fever in children and is difficult to diagnose [5]. Studies have confirmed a genetic association with JIA, depending on its subtype, and it is divided into HLA and non-HLA-related genes [4]. JIA affects children under the age of 16 and affects males and females evenly [5, 6]. JIA is one of the most popular rheumatic diseases in children, affecting 1 to 4 out of every 1000 children and accounting for about 10%–20% of cases. Its clinical manifestations are manifested by fever and skin manifestations, that we find in more than 80% of patients, and musculoskeletal manifestations. The most vulnerable joints are the wrists, knees, and ankles, in addition to the involvement of other organs such as generalized lymphadenopathy, which we see in 25% of patients, hepatosplenomegaly, and chest pain, which can be seen but less frequently [5]. In our case, our patient has generalized joint pain, but blood pressure, heart, and chest auscultation were normal. A serious and deadly complication that can occur in patients with JIA is macrophage activation syndrome, with a prevalence rate of about 10%. There are no laboratory markers to distinguish it from other conditions, but some laboratory abnormalities can help support the diagnosis. Laboratory findings that can be seen in JIA include hypochromic microcytic anemia, leukocytosis (neutrophilia), thrombocytosis, elevated CRP, elevated ESR, elevated ferritin, low albumin, elevated IgG, mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, elevated D-dimers, and negative antibodies [5]. In our case, laboratory testing revealed elevated ESR, CRP, and positive ANA. Anti-CCP, RF, and ASLO were negative. Children with newly diagnosed JIA who are stable without systemic symptoms will receive non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) therapy as a first-line treatment. If there is no improvement within 2 weeks of starting NSAIDs or they have acute systemic symptoms, they will need treatment with systemic corticosteroids or/and biologic therapy. Before starting biological therapy, a tuberculosis test must be performed [5]. Biological drugs that are used: tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) recommended after 3 months of methotrexate (MTX) without improvement or have axial involvement and have not responded to NSAIDs, including etanercept, the first biological agent given to children over 2 years of age with moderate to severe multiple JIA, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, and certolizumab. Other biological agents include anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-1 [7]. Our patient was treated with MTX 2.5, folic acid, and steroids. The patient initially responded, but the symptoms recurred after 4 months, so the patient underwent a transition to biological therapy involving IL-6 antibodies, which led to the complete resolution of symptoms. Subsequently, after a period of 6 years, the patient presented with new clinical manifestations, encompassing restricted wrist joint mobility, proteinuria, heightened creatinine levels, hypertension, and a butterfly rash, prompting the diagnosis of SLE. SLE, a potentially severe autoimmune chronic systemic disease. The incidence of SLE is notably higher in women of childbearing age, showing a female-to-male ratio of 13:1 for those aged 15–44, compared to a ratio of 2:1 in children and in the elderly [2]. Its manifestations are very diverse, from mild skin symptoms to severe organ failure [1]. Our patient suffered from generalized joint pain with no skin manifestation at the first visit. It is more common in women, particularly those of childbearing age. The incidence rate of females to males is 13/1. However, it can also affect children and the elderly, albeit less frequently [2]. We present a case of a child SLE patient. Its pathogenesis is highly complex and involves an intricate interplay between various factors and cells of the immune system. SLE is a mixture involving a combination of genetic, epigenetic, environmental, infectious, and hormonal factors that trigger an immune response [3]. In our case, our patient has a sister with SLE, so there is a genetic factor. Infections indeed represent a significant concern for individuals living with SLE due to the mortality it causes [8]. Our patient suffered from a septic infection, where the causative agent of the infection is unknown due to the impossibility of transplantation due to the financial cost. Therefore she was hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics, including third generation cephalosporins, vancomycin, and steroids, and her condition improved. SLE is known for its ability to affect multiple organs and tissues throughout the body [2]. The clinical manifestations of SLE can vary widely and involve dermatological, renal, neuropsychiatric, and cardiovascular symptoms [9]. Our patient had a pericardial effusion with hypertension and a urinary tract infection detected after the presence of protein in the urine. She had no obvious neurological symptoms, and the cutaneous symptoms were delayed and were characterized by the characteristic butterfly rash of SLE. The skin is the most important site of clinical manifestations of SLE [9]. Skin involvement in SLE occurs in almost 90% of patients and includes acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE), subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) [2]. In our case, the skin symptom lately appeared. Skin manifestations in SLE (malar rash or butterfly-shaped: redness over cheekbones, forming a butterfly-shaped rash across the cheeks and bridge of the nose). Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE): thick blockage of hair follicles, typically occurs on sun-exposed areas such as the face, scalp, and ears. Photosensitivity: skin itchy rash resulting from an unusual reaction to sunlight [10]. In our case, the main skin manifestation was butterfly rash. There is an association between urticarial skin lesions and the DNASE1L3 mutation [3]. The three main symptoms of SLE are in order (fatigue, joint pain, and muscle pain) [11]. Our patient had generalized joint pain with mainly swollen fingers. Clinical symptoms and signs are the basic criterion for diagnosing SLE, in addition to vital laboratory criteria that show the interaction of inflammation with the body's cells. Our patient was tested for RF, anti-CCP, and TB, and all were negative. SLE is considered somewhat difficult to diagnose because only a few patients show symptoms in the early stages of the disease [9]. Our patient was one of those who presented with late symptoms of SLE. As for diagnosing cutaneous lupus, a biopsy is considered the most important procedure [2]. The skin symptoms were finally clinically evident, so we did not need to do a biopsy. There is an association between SCLE and anti-SSA antibodies testing. AhR ratio is an independent cutaneous risk factor associated with disease activity and also accounts for the proportion of hydrocarbon receptor in T cells. About 90%–95% of patients are sensitive to the ANA test. The patient had an ANA antibody test that was positive with a value of 1/160, but this does not mean that its negativity excludes the disease. A biomarker linked to the effectiveness of SLE is anti-dsDNA antibodies [9]. Anti-dsDNA antibodies were positive in our case. The 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criteria for SLE mandate a positive ANA as a prerequisite, followed by weighted criteria across seven clinical domains and three immunological domains. Patients with ≥ 10 points are classified, achieving 96.1% sensitivity and 93.4% specificity in validation, outperforming the ACR 1997 and SLICC 2012 criteria [12]. Our study prioritizes unique clinical presentations over systematic classification; thus, we did not apply the 2019 EULAR/ACR criteria. Diagnosis was established through an extensive review of clinical symptoms, laboratory data, and patient history. As for the management of end-stage renal disease, immunosuppressants (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate, and tacrolimus) are better than corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine is important for relieving the development of skin symptoms. They also suffer from vitamin D deficiency [2]. To treat skin and joint symptoms, we noticed that MTX is very powerful in improving the condition as a whole and the level of anti-dsDNA in particular. About 80% of organ failure cases are attributable to prednisolone use [2]. Corticosteroids were stopped immediately after the diagnosis and started biological therapy with 13 doses of IL6 antibodies actemra, then with generalized joint swelling, especially the wrist, it was replaced with remicade TNF antibodies, while with pigment changes in the eye, it was given altepril, while after the appearance of signs of SLE, all previous drugs were stopped and immunotherapy was started with SLE, celsept, placo, RAMP, and amlodipine with the observation that the patient improved well. Regular exercise, especially stretching exercises, is important to relieve muscle pain and fatigue [2]. The patient is actively pursuing a return to her usual daily activities.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, SLE and JIA represent complex autoimmune conditions with diverse clinical presentations and diagnostic challenges. The case discussed underscores the importance of considering the possibility of evolving or overlapping autoimmune conditions, particularly when a patient's symptoms change over time. It also emphasizes the need for ongoing monitoring and reevaluation to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. The multifactorial nature of these diseases further highlights the importance of individualized treatment strategies tailored to each patient's unique clinical profile.

Author Contributions

Saja Karaja: data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Mai Halloum: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Joudy Sheikh Taha: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Ayham Qatza: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Ahmad Alsayadi: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Ghofran Al Mansour: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Muhannad Abokurshah: supervision, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Ethics Statement

Ethics clearance was not necessary since the University waives ethics approval for publication of case reports involving no patients' images, and the case report is not containing any personal information. The ethical approval is obligatory for research that involve human or animal experiments.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.