Primary hyperaldosteronism secondary to right adrenal hyperplasia with non-functioning left adrenal adenoma elucidated by adrenal vein sampling: A case report with in-depth physiological review on utility of aldosterone renin ratio

Adam Tuchinsky and Sundus Sardar are co-first authors.

Key Clinical Message

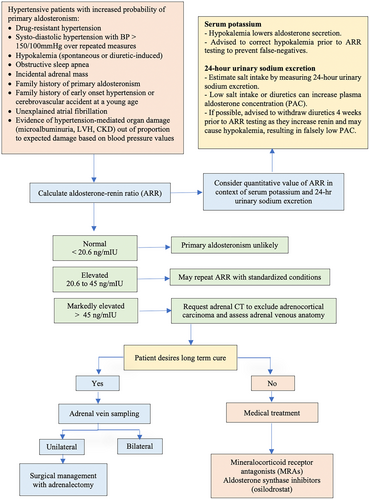

In cases of primary hyperaldosteronism, the aldosterone renin ratio (ARR) is crucial for determining the need for adrenal vein sampling (AVS). Our case highlights the importance of utilizing ARR with AVS, contextual interpretation of plasma renin and aldosterone levels, and stresses that sole reliance on imaging without AVS may result in unnecessary or contralateral adrenalectomy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Understanding adrenal gland tumors requires a comprehension of adrenal histology. The adrenal gland is comprised of an outer capsule, cortex, and medulla. In the cortex starting from outer to innermost layer, is the zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculate, and the zona reticularis. The mineralocorticoids, are produced in the zona glomerulosa, glucocorticoids are produced in the zona fasciculata, progesterone, testosterone, and estrogen are produced in the zona reticularis and catecholamines are produced in the medulla. Excess production of these is most driven from adenomas in each of their respective regions. Specifically, glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid excess production are known as the Cushing and Conn syndromes, respectively.

Conn syndrome was named after Dr. Jerome W. Conn, who first described what we now would categorize more broadly as primary hyperaldosteronism in 1955. Originally, Conn syndrome was only referring to hyperaldosteronism driven by an active adenoma. Currently, the more inclusive term primary hyperaldosteronism is used interchangeably with Conn syndrome.1 Primary aldosteronism is a syndrome in which aldosterone is excreted regardless of physiologic stimulating pathways most notable the renin angiotensin aldosterone (RAAS) system. Hyperaldosteronism classically presents as hypertension (HTN), hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis.

Aldosterone is a pregnane-based steroidal hormone, synthesized, and secreted in response to two main triggers.2 The first being RAAS activation, and the second being high dietary potassium sensed in the zona glomerulosa.3 With RAAS activation, aldosterone acts in the cortical collecting tubule on the principal cells, causing sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion.3, 4 Its acid–base effects take place as well in the cortical collecting tubule on the alpha intercalated cells, where it excretes hydrogen ions in exchange for potassium ions.5, 6 While hypokalemia is classically associated with primary aldosteronism, a retrospective study from five different continents found only between 9% and 37% of patients with primary aldosteronism had hypokalemia.7

Primary hyperaldosteronism includes two main subtypes, namely idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (also termed bilateral adrenal hyperplasia (BAH)) and unilateral aldosterone-producing adenoma, managed with aldosterone antagonists or adrenalectomy, respectively. Aldosterone renin ratio (ARR) has emerged as a significant parameter as compared to plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC), thus identifying need for adrenal vein sampling (AVS) or further exclusionary tests including imaging, the solitary utility of which without AVS may result in unwarranted adrenalectomy. Our case demonstrates the importance of AVS and elaborates the context that needs to be applied to plasma renin and aldosterone levels.

2 CASE HISTORY AND EXAMINATION

We present the case of a 68-year-old male with a history of type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease status post two stents placed around 15 years prior, hyperlipidemia, and GERD, who was referred to a nephrologist due to refractory HTN. The patient was originally diagnosed with HTN in his 40s and had achieved good control using a drug regimen with three to four antihypertensive agents. He later developed HTN refractory to these medications. His blood pressure regiment was escalated to six antihypertensive agents which included, carvedilol 25 twice a day, doxazosin 2 mg twice a day, hydrochlorothiazide 50 mg daily, isosorbide mononitrate 30 mg daily, losartan 100 mg daily, and spironolactone 50 mg daily. Due to dizziness and lightheadedness, the patient preferred twice-a-day dosing. At that time, the patient's laboratory tests were significant for microalbuminuria; however, his acid–base status, potassium, renin, and aldosterone levels were all within normal limits.

Upon nephrology clinic visit, his blood pressure was noted at 163/90, and physical exam was only significant for trace edema. Retroperitoneal ultrasound and laboratory tests, which included a secondary hypertensive work up, were obtained. Laboratory tests showed normal free metanephrines of 0.33 nmol/L, normetanephrines 0.92 nmol/L, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 3.45 μLU/mL, serum creatinine 1.11 mg/dL, potassium 4.3 mEq/L, bicarbonate 24 mEq/L, BUN 15 mg/dL, microalbumin to creatinine ratio 268 mg/g, WBC 7600/μL, hemoglobin 14.8 g/dL, platelet count 229/μL; renin, aldosterone, and cortisol were within normal limits.

2.1 Differential diagnosis and treatment

Imaging showed no significant stenosis of bilateral renal arteries, patent bilateral renal veins; right and left kidneys measured 11.8 and 12.0 cm, respectively.

The following appointment, the patient's blood pressure medications were optimized, doxazosin was increased, and hydralazine was initiated, with excellent response. The patient developed gynecomastia and breast tenderness. At first, the spironolactone dose was reduced, then eventually discontinued and replaced with eplerenone. Unfortunately, he was unable to tolerate eplerenone, as it caused severe headaches and dizziness. Eventually, amiloride was added, and hydralazine was increased; this regimen led to better blood pressure control once again.

A few months later, the patient again noted worsening uncontrolled HTN. This led to the addition of amlodipine. In context of refractory HTN, repeat laboratory tests were performed, which were significant for aldosterone of 40.1 ng/dL, plasma renin activity (PRA) of 0.9 ng/mL/h, free metanephrines and normetanephrines, were both within normal limits at 0.26, and 0.92 nmol/L, respectively. The ARR was calculated at 44.6. The algorithm for the ARR evaluation is depicted in Figure 1.8 To ensure the accuracy of the PAC, urine sodium and 24-h aldosterone were obtained at the time of previous lab collection. Urine aldosterone was 42 mcg/24 h, and urine sodium 178 mEq/24 h. He underwent a CT abdomen and pelvis without contrast, which showed a small left adrenal lipid-rich adenoma approximately 13 × 11 mm, and bilateral adrenal gland thickening. The patient subsequently underwent AVS, in which right adrenal vein aldosterone and cortisol, notable at 4880 ng/dL, and 1158 μg/dL, respectively, a ratio of 4.2. The left adrenal vein aldosterone and cortisol noted at 146 ng/dL and 495 μg/dL, respectively, a ratio of 0.3. In addition, a cortisol-corrected PAC lateralization ratio of 14.3 on the right. In the clinical documentation, it was noted that special precautions were in place and followed to ensure the samples were not mixed up.

2.2 Outcome and follow-up

He underwent laparoscopic right adrenalectomy with pathology confirming adrenocortical adenoma. Postoperative follow up showed significant improvement in HTN on fewer antihypertensive agents, decreased aldosterone of 7.8 ng/dL, PRA of 0.5 ng/mL/h, and ARR of 15.6.

3 DISCUSSION

We have reported the case of primary hyperaldosteronism secondary to right adrenal hyperplasia with non-functioning left adrenal adenoma elucidated by ARR and AVS. Diagnosis of primary aldosteronism is demonstrated with inappropriately high aldosterone for a given expected physiologic state, and importantly low or undetectable renin.8 In primary aldosteronism, the driver of low renin is due to feedback inhibition from the elevated aldosterone. RAAS activation which terminates in aldosterone excretion, leads to intravascular volume expansion, and increases renal perfusion and glomerular filtration rate, which eventually via a negative feedback loop, will decrease renin secretion.9

Since primary aldosteronism reflects both elevated aldosterone and suppressed renin, the ARR was proposed by Hiramatsu in 1981 as a screening method.10, 11 ARR has replaced single analysis with plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC), given the aldosterone levels need to be evaluated in the context of renin. Therefore, the ARR is used in conjunction with either PRA, or direct renin concentration (DRC). One caveat is that the ARR can become inaccurate in the low spectrum of renin levels.8 This can be avoided by setting a minimum value of renin, 0.2 ng/mL/h for PRA or 2 mIU/I for DRC.8

The greatest challenge in diagnosing primary aldosteronism is the numerous variable factors that influence aldosterone levels. This makes the accuracy of the PAC dependent on multiple factors, including, hypokalemia, salt intake, diuretics, positioning before blood draw, and the handling of the sample.

Additionally, the ARR is impacted by multiple antihypertensive medications, including beta blockers, central acting alpha-2 agonists, potassium sparing and wasting diuretics, and ACE inhibitors/ARBs.8 This may result in a great challenge for HTN management during PAC and PRC testing if temporary discontinuation is contemplated. There are substitute medications which have a minimal effect on the ARR, some of them include verapamil, hydralazine, prazosin, doxazosin, and terazosin.12 However, even if the patient's current HTN does not allow for discontinuation of medications known to affect the ARR, this can be considered when assessing ARR.8, 12

Common subtypes of primary aldosteronism can be divided into surgically curable versus not surgically curable. Surgically curable etiologies include, aldosterone producing adenomas (APA) both unilateral and bilateral, primary multinodular unilateral adrenocortical hyperplasia, ovary aldosterone-secreting tumor, bilateral adrenocortical hyperplasia with concomitant pheochromocytoma, and aldosterone-producing carcinoma (APC). Surgically not curable forms include, BAH, unilateral APA with BAH (aldosterone producing cell clusters), familial hyperaldosteronism type I (glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism), and familial hyperaldosteronism type II-V.8

An ARR greater than 20.6 but less than 45 would require further exclusionary testing, including oral sodium loading, intravenous saline test, the captopril challenge test, and the fludrocortisone with salt loading test. All of these tests found physiologically suppress aldosterone, clarifying if further testing is necessary.

Given the complexity of obtaining true ARR, and to prevent false positives ARR, laboratory tests need to be conducted in a rather controlled sodium intake setting. This has been described as aldosterone suppression testing.13 As decreased sodium intake will cause a physiologic increase, hence increased sodium intake should cause a physiologic decrease of the ARR, thus causing the suppression. Therefore, oral sodium loading is preformed while obtaining the ARR. This is preformed over 3 days, with a goal oral sodium being 5 g. On the third day, serum electrolytes and 24-h urine specimen are collected for measurement of aldosterone, sodium, and creatinine. According to criteria, 24-h urine sodium excretion should exceed 200 mEq (4600 mg) for adequate assessment. Urine aldosterone excretion can be used as a marker as well, with urine aldosterone excretion >12 mcg/24 h suggesting hyperaldosteronism. Another method of sodium loading can be with IV fluids, with 2 L given over a 4-h period.4

If the ARR is not suppressed by aforementioned challenges or there is an initial ARR greater than 45, adrenal imaging is indicated. Imaging is indicated to exclude an APC and identify adrenal venous drainage.14 Once imaging is preformed and there is desire for long-term cure, adrenal venous sampling (AVS) is then indicated. If long term cure is not desirable or AVS is indicating a non-surgical option, medical therapy is indicated. Medical therapy, with management of HTN, hypokalemia, treatment directed against the mineralocorticoid receptor and geared towards lowering renin levels.15

The importance of AVS cannot be overstated, as following imaging alone can lead unnecessary or ineffective adrenalectomy. One study reported that based on CT findings alone, “around 21% of patients would have been incorrectly excluded as candidates for adrenalectomy, and 48 (24.7%) might have had unnecessary or inappropriate adrenalectomy.”16 AVS allows for the measurement of PAC off both adrenals separately, which elucidates the difference between a unilateral adenoma, and bilateral hyperplasia.17 Typically, unilateral disease will cause marked increase in PAC compared to the contralateral side. While in BAH, both sides PAC would be similar. While preforming the AVS some protocols call for continuous cosyntropin infusion (CCI), which has multiple benefits. CCI acts to minimize stress stimulated variations in aldosterone secretion, confirms AVS as this would be lowered if the inferior vena cava was accessed, and maximize the secretion of aldosterone from an APA.18 With CCI adrenal vein IVC cortisol ratio is typically 10:1, with a minimal ratio of 5:1 in order to be confident of your sampling site. When CCI is not used, adrenal vein to IVC cortisol ratio of more than 3:1 is recommended for assessment of successful access.16

Laboratory data can also be used to calculate the cortisol-corrected ratios (CCRs), which is calculated as a ratio of PAC to cortisol concentrations. For unilateral aldosterone hypersecretion, there should be a minimal ratio of 4:1 or greater.16 A ratio less than 3:1, suggests bilateral excess, and ratios greater than 3 but less than 4, normally have intersecting pathologies.

4 CONCLUSION

Diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism may be challenging and often overlooked. PAC may be challenging to interpret due to many influencing factors; hence, ARR is emerging as a beneficial parameter to delineate the initial diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism. Our case highlights the pertinent features for diagnosis of primary aldosteronism and also emphasizes the utility of ARR. And cortisol-corrected PAC laterization ratio in these cases. While AVS may appear counterintuitive, it is prudent to consider AVS for confirmation prior to adrenalectomy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Adam Tuchinsky: Visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Sundus Sardar: Conceptualization; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Abdel-Rauof M. Akkari: Visualization; writing – review and editing. Ahmad Samir Matarneh: Visualization; writing – review and editing. Gia Susan John: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Nasrollah Ghahramani: Supervision; visualization; writing – review and editing. Umar Farooq: Conceptualization; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Nephrology Division at Penn State Health for providing us the opportunity and support to conduct this work.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors have no funding to disclose in relations to this case report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors associated with this case report have no actual or possible conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All the all procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.