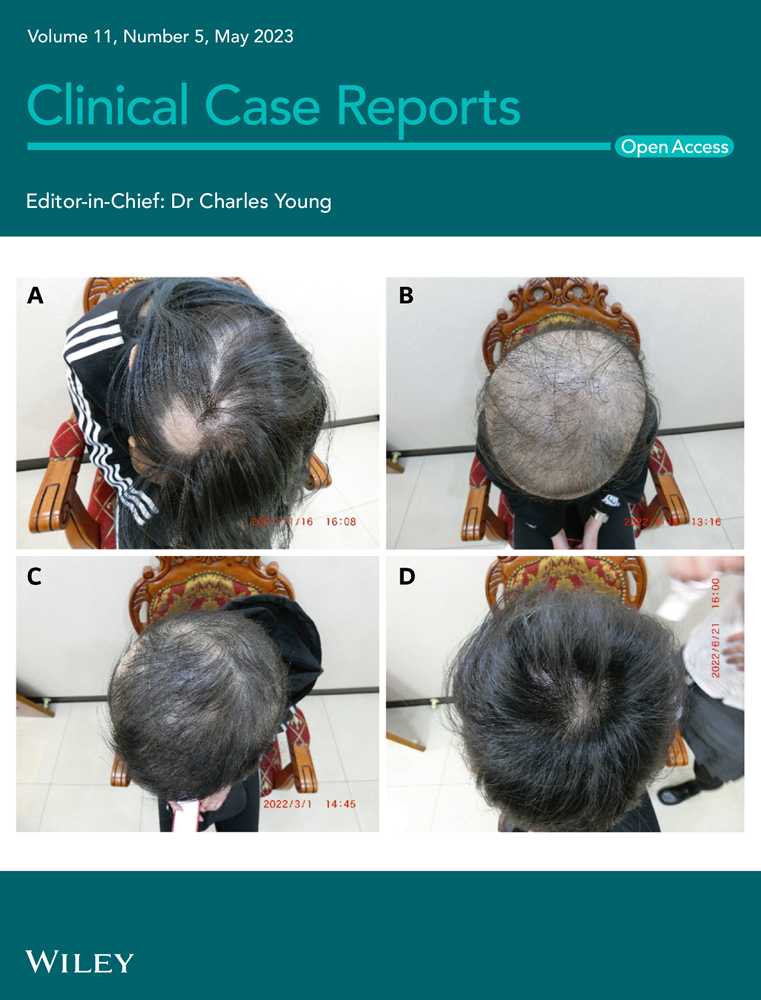

A large intracardiac hydatid cyst with concomitant cervical and hepatic involvement: A case report

Abstract

Key Clinical Message

Cardiac hydatidosis is a relatively rare complication of echinococcosis. Understanding the atypical manifestations, potential associated risk factors, and epidemiology leads to optimal and timely management.

Cardiac hydatidosis is a relatively rare complication of echinococcosis, with a potentially life-threatening condition. Here, we reported a large interventricular septal hydatid cyst bulging in the left ventricle accompanied by a huge cervical lamp with recurrent hepatic cysts that underwent cardiac surgery to excise the cyst uneventfully.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cystic echinococcosis is a protozoal infectious disease caused by most of the Echinococcus species commonly affecting the liver and lungs (two-thirds and one-fourth of all reported cases, respectively), with rare involvement of cardiac tissue (less than 2%).1

This case highlights the rare concomitant cardiac, cervical, and hepatic involvement with hydatid disease. Together, a good understanding of the atypical manifestations, potential associated risk factors, and epidemiology leads to the optimal and timely management of such patients to minimize worse outcomes.

2 CASE PRESENTATION

A 68-year-old woman presented to a health care center with a clinical manifestation of a slow-growing and painless lump on the right side of the cervical region over several weeks. She had no cardiac symptoms. History-taking revealed working in a sheep farming area in her twenties. Past medical and surgical history included hypertension and hepatic hydatidectomy 2 years ago.

Ultrasound imaging revealed a 47 mm × 75 mm cervical cyst expanded to the superior mediastinum with neither inflammatory response nor spasm of the cervical muscles. The cervical cyst consisted of a bilayer membrane with several membrane-attached scolices, indicating an active hydatid cyst (cystic echinococcosis type 1, CE1). The lesion was lateral to the common carotid artery and posterior to the internal jugular vein with no cervical lymphadenopathy. Besides, the abdominal ultrasound examination showed multiple active, recurrent hepatic cysts in both the right and left lobes (stage 1), encompassing all liver segments. There was no evidence of biliary dilatation as well.

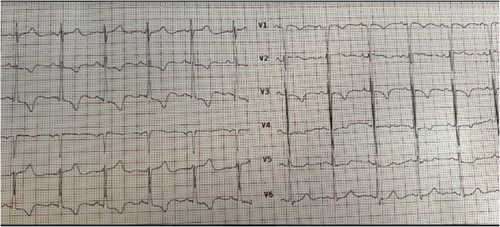

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm, and right axis deviation, with inverted T waves in inferior and V2-V3 leads. There is no evidence in favor of an atrioventricular block (Figure 1).

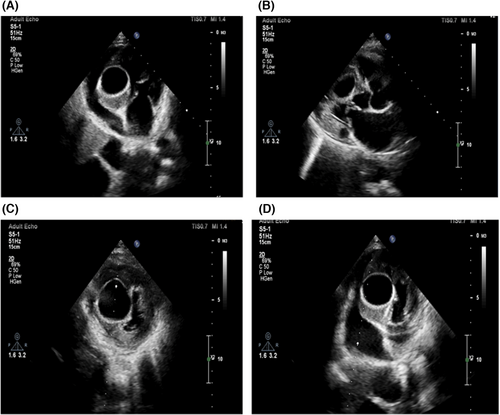

In the transthoracic echocardiographic (TTE), a bulging and well-defined echo-lucent cystic mass in the interventricular septum measuring 33 × 42 mm was detected (Figure 2). A slight compression effect was present on the right ventricle (RV) cavity. The LV size and LV outflow tract (LVOT) were normal, with a mild systolic dysfunction (eyeball estimation of LV ejection fraction = 45%–50%). The valvular functions were normal, with no pericardial effusion. Other echocardiographic findings were unremarkable. The hydatid serology was positive, in which the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based qualitative assessment of E. granulosus IgG antibodies confirmed the echinococcosis. Treatment with antiprotozoal medication was started. After 2 weeks, the patient underwent coronary angiography, which was normal. Cardiac surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) for cystectomy was persuaded to minimize the risk of cyst contents spillage. The CPB technique was established by cannula inserting into the ascending aorta, superior vena cava (SVC), and inferior vena cava (IVC) after the routine median sternotomy.

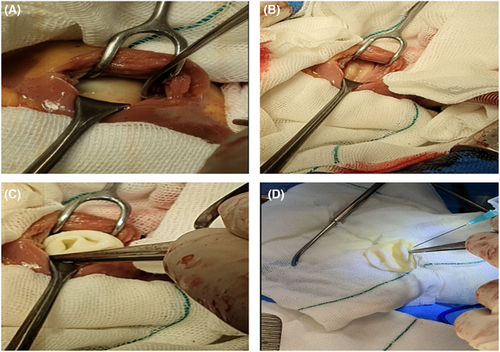

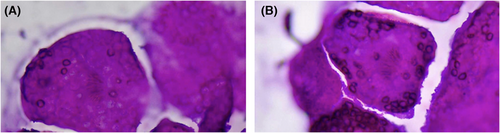

Following the cold cardioplegia, the established hypothermia was recorded at 32°C. The outlines of the isolated cardiac cyst seemed to be complete and clear. Conservative procedures were further performed to sterilize and evacuate the cyst contents. The RV cavity was entered, and the cyst was exposed carefully. Thereafter, 10 mL of its contents were aspirated. An equal amount of hypertonic saline (NS 20%) was injected into the cyst, and after several minutes, the exposed cyst was evacuated completely (Figure 3). Following successful excision and secured hemostasis, the cyst specimen, containing 8 mL colorless turbid fluid, was sent to the histopathological examination, which further vouched for the diagnosis of a hydatid cyst (Figure 4). The surgery was successfully terminated with a good recovery phase. A few days later, she was discharged on the anthelminthic drug (albendazole). She had no complications on the first outpatient visit 1 week after discharge. The 3-month follow-up was satisfactory.

3 DISCUSSION

According to the WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis (WHO-IWGE) ultrasound classification, hydatid cyst consists of three stages, including active (CE1, CE2, with a high-risk of rupture), transitional (CE3), and inactive or calcified cysts (CE4, CE5, with a low-risk of rupture).1 The liver and lungs are the most common organs of hydatid involvement. In half of such cardiac cases, multiple organ involvement is also reported.2 Since cardiac hydatidosis has the propensity to be enlarged, further pressure over the myocardium results in ventricular dysfunction, mechanical obstruction of atrioventricular valves, and displacement of coronary vessels.3 Irrespective of the size and stage, it can cause potentially lethal arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia),4 and high-grade atrioventricular block.

Peripheral embolization, anaphylactic reactions, and sudden death5-7 occur following the cyst rupture or left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO).8 Although most infected patients are asymptomatic, some clinical manifestations, such as dyspnea, chest pain, syncope, and palpitation, can be observed in a minority of cases. In light of the mostly asymptomatic entity of the cardiac hydatid cyst, echocardiography with high sensitivity and specificity is considered an imaging method of choice regarding cyst location, size, scolices presence, and evaluation of the possible pressure on other parts of the heart.9 Even so, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), plain chest X-ray, and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) are known as other valuable diagnostic measures.10, 11 Beyond the imaging tools, serology and pathohistological examinations would be helpful aids in confirming disease diagnosis. Hitherto, complete surgical excision remains a preferred therapeutic option. Moreover, albendazole/mebendazole12 and praziquantel are prescribed as adjuvant pharmacotherapy.1

Although most cardiac hydatic cysts in the literature are reported in young patients, we reported an old lady (68 y/o) with a recurrent hepatic hydatidosis accompanied by a huge homogenous cystic mass in the cervical and intracardiac regions. In our case, the cystic lesions near the portal venous confluence and the left portal vein may be the leading cause of extrahepatic hydatidosis. It is worth noting that the multiplicity and dispersion of the lesions, typical imaging findings, a history of husbandry procedures, a history of hepatic cysts, geographic location, and positive result of serologic test strongly established the hydatid cyst diagnosis. A previous study represented a 70 y/o female with no history of being in a sheep rising area with signs in favor of right heart failure and cardiac hydatidosis complicated hydatid cyst and pretamponade.13 Shojaei et al., in Iran, also reported a cardiac HC in a 70-year-old farmer with dyspnea. The isolated lesion was diagnosed by echocardiography and further confirmed with cardiac MRI. Despite successful surgical excision, he died due to a progressive arrhythmia.14 Another report in Iran has also documented an echinococcal infection involving an intramyocardial multicystic lump in the posterolateral and basal inferoseptal segments of LV in a 57-year-old farmer man referred with chest pain, and diagnosed by echocardiography, CMR, and positive ELISA-based serologic test. In contrast to our finding, EKG examination showed pathological Q and negative T waves. Similarly, surgery was the treatment of choice, followed by albendazole as a complementary therapy.3

In conclusion, a good understanding of the atypical manifestations, potential associated risk factors, and epidemiology leads to the optimal and timely management of patients with rare echinococcosis to minimize worse outcomes.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Maryam Faramarzpour: Project administration; resources; writing – original draft. Sirous Jafari: Project administration; resources. Mehrzad Rahmanian: Resources. Akram Sardari: Writing – original draft. Farnoosh Larti: Conceptualization; resources; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was received for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest was present to be disclosed.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient regarding this research process.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data of this study are available for further assessment.