Giardiasis: Report of a Case Refractory to Treatment

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Giardiasis, an intestinal infection caused by Giardia duodenalis, remains a significant global health concern. Although standard treatments such as metronidazole are typically effective, there are increasing reports of treatment resistance, highlighting the need for alternative therapeutic strategies for which established guidelines do not exist. This case report illustrates the challenges in diagnosing and managing treatment-refractory giardiasis. A 32-year-old male presented with chronic symptoms of watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and significant weight loss, despite multiple rounds of standard therapies, including metronidazole and albendazole. The persistent presence of Giardia lamblia in stool samples despite appropriate treatments, underscores the necessity for clinicians to recognize treatment failures and explore alternative strategies in the absence of standard protocols. This instance, prolonged combination therapy with metronidazole and albendazole proved effective after previous treatment failures, resulting in symptom resolution and negative stool tests. Clinicians should consider treatment-refractory giardiasis as a differential diagnosis in patients with chronic gastrointestinal complaints and a history of giardiasis treatment, enabling earlier diagnosis and intervention. This case emphasizes the need for ongoing monitoring of treatment-refractory giardiasis and calls for further study of resistant strains. It also provides an effective approach for managing cases of treatment-resistant giardiasis.

Summary

- Giardiasis, caused by Giardia duodenalis, poses diagnostic and management challenges in treatment-resistant cases.

- This report highlights persistent symptoms despite standard therapies and the success of prolonged metronidazole-albendazole combination therapy.

- It underscores the importance of recognizing treatment failures, monitoring refractory cases, and advancing research to address resistant strains effectively.

1 Introduction

Giardiasis is protozoa infection that affects the small intestine. It is caused by the protozoa Giardia duodenalis [1]. It is a common disease in developing countries, estimates showing 33% of the population been infected. In developed country this number is lower, and most cases are due to travel. Transmission is through ingestion of the cyst, which is the resistant form of the protozoa, through contaminated water or direct person to person contact [2]. The clinical manifestation is heterogeneous, half being asymptomatic and rest presenting with abdominal pain, nausea, watery diarrhea, and steatorrhea. In giardiasis, the acute pathophysiology occurs without invasion of the small intestinal tissues by the trophozoites, and in the absence of overt inflammatory cell infiltration, with the exception of a modest increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes [3-5]. In chronic infections patient can present with recurrent diarrhea leads to malabsorption, weight loss and vitamin deficiency [6]. Multiple factors have been proposed to account for the disease variability, including the state of the host immune system, host age and nutritional status, strain genotype, infectious dose and possibly co-infections [7-9]. The pathophysiological consequences of Giardia infection are clearly multifactorial, and involve both host and parasite factors, as well as immunological and non-immunological mucosal processes. Recent observations suggest a role for disruptions of the host intestinal microbiota during the acute infection stage in the production of chronic symptoms, and further research is warranted to corroborate these findings [10].

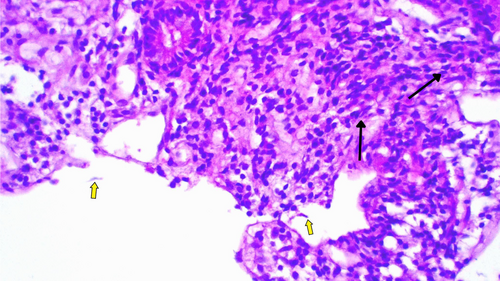

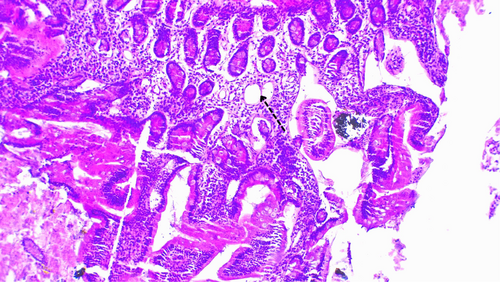

The diagnosis is commonly through visualization of the cyst or trophozite by direct light microscopy from the stool. The cyst is the stage most commonly found in non-diarrheal feces. But stool antigen detection assays and nucleic acid amplification tests are also available and are more sensitive and specific [11]. A biopsy is rarely necessary for suspected giardiasis evaluation. However, when obtained in the evaluation of chronic diarrhea, the histopathological analysis may reveal normal to subtotal villous atrophy, with the degree of atrophy corresponding to the disease's severity. After treatment and symptom improvement, a follow-up biopsy typically reveals the restoration of typical villous architecture.

Among the different antimicrobial options for treatment of giardiasis, first line is metronidazole. Other regimens which show to be effective include tinidazole, nitazoxanide, mebendazole, albendazole and paromomycin. In most cases, parasitological cure is achievable. Rarely the protozoa persist, and which signifies treatment failure. We present a case report of giardiasis refractory to treatment [12, 13].

2 Case Presentation

A 32-year-old male patient from Jimma, Ethiopia, presented with watery diarrhea occurring two to three times daily for the past 7 months. He has a history of treatment for giardiasis on two occasions. The first treatment was 5 years ago (2019) while he was a university student. After receiving a single dose of 2 g of tinidazole, his symptoms improved, and stool examination showed no ova or parasites.

In June 2020, the patient was diagnosed with dyspepsia and treated with proton pump inhibitors. By October 2021, he required treatment for perforated peptic ulcer disease (PUD) after presenting with severe epigastric pain and vomiting for one day. He improved after a 10-day hospital stay.

In September 2021, the patient experienced crampy abdominal pain and intermittent diarrhea. He was treated for giardiasis, confirmed by the detection of Giardia lamblia trophozoites in fecal smears. He received oral metronidazole 500 mg three times daily for 7 days, resulting in clinical improvement and a negative fecal smear.

In September 2023, the patient presented with persistent and voluminous watery diarrhea (two loose stools), associated with intermittent crampy abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, loss of appetite, and significant weight loss (10 kg). Detailed investigations (Table 1) confirmed giardiasis again by detecting G. lamblia trophozoites in stool samples.

| Laboratory investigation | Patient value | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count (WBC) | 3.5 × 109/L | 4.5–11 × 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 15.7 g/dL | 13.2–16.6 g/dL |

| Platelets | 271 × 109/L | 165–415 × 109/L |

| Serum sodium | 141 mmol/L | 137–145 mmol/L |

| Serum potassium | 4.4 mmol/L | 2.7–3.9 mmol/L |

| Serum chloride | 109 mmol/L | 116–122 mmol/L |

| Serum total calcium | 8.8 mg/dL | 8.6–10.3 mg/dL |

| Serum phosphorus | 2.2 mg/dL | 2.7–4.5 mg/dL |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 120 IU/L | 105–333 IU/L |

| Total protein | 7.2 g/dL | 6.6–8.7 g/dL |

| Serum albumin | 4.7 g/dL | 3.4–5.4 g/dL |

| Total serum iron | 125 Ug/dL | 65–175 Ug/dL |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | 10 mm/h | ≤ 15 mm/h |

| Serum creatinine | 0.9 mg/dL | 0.7–1.3 g/dL |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | 7 mg/dL | 7–20 mg/dL |

| Aspartate transferase | 17 U/L | 8–33 U/L |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) | 7 U/L | 4–36 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 54 IU/L | 44–147 IU/L |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) | 20 U/L | 12–64 U/L |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.4 mg/dL | < 0.3 mg/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 0.7 mg/dL | 0.1–1.2 mg/dL |

| Amylase | 107 IU/L | 25–125 IU/L |

| Lipase | 38 IU/L | 8–78 IU/L |

| Total cholesterol | 72 mg/dL | 0–200 mg/dL |

| High density lipoprotein (HDL) | 29 mg/dL | 40–60 mg/dL |

| Triglyceride | 83 mg/dL | 0–150 mg/dL |

| (low-density lipoprotein ldl) | 26 mg/dL | 0–130 mg/dL |

| Hepatitis surface antigen | Negative | — |

| Hepatitis C antibody | Negative | |

| HIV antibody test | Negative | — |

| Blood in the Urine | Negative | — |

| Occult stool examination | Negative | — |

| GeneXpert | M.TB not detected | |

| Tissue Transglutaminase (tTG) Antibody | 0.77 U/mL | < 4.00 |

| Immunoglobulin IgA | 168 mg/dL | 40–350 mg/dL |

| Immunoglobulin IgG | 1289 mg/dL | 650–1600 mg/dL |

| Immunoglobulin IgM | 51.85 mg/dL | 50–300 mg/dL |

| Sonography of the abdomen | Normal | |

| Study upper gastro intestinal endoscopy revealed | GERD(gastro intestinal reflux disease)- | |

| Duodenitis- with mild inflammation and deformity of the lumen | ||

| Duodenal biopsy | Shortened and widened villi containing increased lymphocytes, plasma cell |

The patient had been using tap water for drinking over the past year before presentation but switched to bottled water after being advised by the treating team. He has no history of other chronic medical illnesses. Upon physical examination, his blood pressure was 118/65 mmHg, pulse rate 88 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and temperature 36.5°C. Oxygen saturation in room air was 96%. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

3 Investigation and Treatment

Initially, the patient was treated with a 7-day course of oral metronidazole 500 mg three times daily after stool examination confirmed giardiasis. Although the frequency of diarrhea decreased and the number of trophozoites in stool samples reduced, there was no significant overall improvement. Considering the lack of improvement, the patients' history of perforated PUD and long standing symptoms, we did an upper GI endoscopy with duodenal biopsy, tissue transglutaminase with immunoglobulins level (Table 1) to rule out celiac disease and gastric cancer. The results of the biopsy (Figures 1 and 2) confirmed the diagnosis of giardiasis. Subsequently the patient was given secnidazole 500 mg orally daily for 3 days, followed by diloxanide furoate 500 mg three times daily for 10 days (Table 2). This led to partial improvement of symptoms, but they reappeared after completing the therapy. Subsequent treatment with albendazole was also unsuccessful, showing only transient improvement during treatment, with persistent Giardia trophozoites in stool samples (Table 3).

| Date | Drug | Dosage and duration of treatment |

|---|---|---|

| 28/04/19 | Tinidazole | 2 g po single dose |

| 17/09/21 | Metronidazole | 500 mg po tid for 7 days |

| 23/09/23 | Albendazole | 400 mg po daily for 3 days |

| 09/11/23 | Metronidazole | 500 mg po tid for 7 days |

| 10/01/24 | Secnidazol | 500 mg po daily for 3 days |

| 08/02/24 | Tinidazole Cyprus and Albendazole | 500 mg po and 400 mg po daily for 3 days |

| 18/03/24 | Diloxanide Furoate | 500 mg po tid for 10 days |

| 07/04/24 | Metronidazole | 500 mg IV tid for 7 days |

| 26/04/24 | Albendazole and Metronidazole | 400 mg po bid and 500 mg po tid together for 3 weeks |

| Date (d/m/y); parasite morphology | Cysts of G. lamblia | Trophozoites of G. lamblia |

|---|---|---|

| 28/04/19 | − | + |

| 17/09/21 | − | + |

| 23/09/23 | − | + |

| 09/11/23 | − | + |

| 10/01/24 | − | + |

| 08/02/24 | − | + |

| 18/03/24 | − | + |

| 07/04/24 | − | + |

| 05/05/24 | − | + |

| 12/05/24 | − | − |

| 19/05/24 | − | − |

| 26/05/24 | − | − |

| 03/06/24 | − | − |

| 04/07/2024 | − | − |

| 03/08/2024 | − | − |

- Abbreviations: −, negative; +, positive; d/m/y, day/month/year.

4 Out Come and Follow Up

Finally, the patient was started on a combination treatment of metronidazole 500 mg orally three times daily and albendazole 400 mg orally two times daily. After this combination therapy, the symptoms improved, but stool tests remained positive for the first 2 weeks. After 3 weeks of treatment, stool exams showed persistently negative results (Table 3), and the patient's symptoms improved with a weight gain of 3 kg over the 2 months following treatment.

5 Discussion

The patient described is a 32-year-old immunocompetent man with a history of recurrent giardiasis. His earlier episodes of giardiasis were successfully treated, leading to complete resolution of symptoms and parasitological clearance. However, in the current presentation, the patient exhibited symptoms indicative of a chronic giardia infection, which was confirmed by positive stool examination. Despite treatment with various antiprotozoal medications, no parasitological cure was achieved.

Given the chronic nature of his symptoms, along with a history of chronic peptic ulcer disease and weight loss, the patient underwent further investigations, including upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, biopsy, quantitative immunoglobulin levels, and tissue transglutaminase levels. These investigations suggested a diagnosis of chronic giardiasis refractory to standard treatment.

Treatment-refractory giardiasis has been increasingly reported, likely due to improved diagnostic sensitivity and reporting practices. A study of 170 giardiasis cases in Madrid from 1989 to 1994 found that 5.8% of cases failed one or more initial 5-nitroimidazole-containing regimens [14]. More recent studies in Spain and the Czech Republic have reported even higher rates of treatment failure, at 20% and 22%, respectively [15, 16]. Common causes of refractory giardiasis include resistant strains, repeated infections, inappropriate drug administration, and the patient's immunological status [17].

Despite the increasing prevalence of treatment-refractory cases, management strategies are primarily based on clinical experience due to the lack of well-designed trials and standardized treatment protocols. Initial treatment for giardiasis typically involves 5-nitroimidazoles, particularly metronidazole and tinidazole. Alternative options include nitazoxanide, albendazole, mebendazole, secnidazole, paromomycin, furazolidone, and quinacrine. For refractory cases, monotherapy, even with increased dose or duration, or switching to another first-line treatment has often proven ineffective. Consequently, combination therapy is recommended [18].

Combination therapy with albendazole and metronidazole has shown success in 79% of patients with metronidazole-refractory giardiasis, as reported in a study conducted in Norway [19]. In this study, six patients who did not respond to the initial regimen were subsequently treated with paromomycin, achieving a 50% success rate. Additionally, a combination of 100 mg quinacrine BID with a higher dose of 750 mg metronidazole TID for 2–3 weeks was effective in the remaining three cases. Another report demonstrated successful treatment of 5 out of 6 refractory cases by combining quinacrine with either metronidazole or tinidazole [17]. A case series involving ten patients with refractory giardiasis achieved both clinical and parasitological cure in all cases when treated with a combination of metronidazole, tinidazole, paromomycin, or albendazole [20].

In the present case report, treatment-refractory chronic giardiasis was diagnosed through duodenal biopsy and stool parasitological examination. We evaluated potential causes of treatment failure by assessing treatment adherence, checking for immunosuppression, and ruling out re-infection. The patient was managed with various monotherapy medications, increasing doses and durations, and subsequently treated with combination therapy involving two antigiardial drugs. Despite these efforts, the patient remained refractory to treatment, with parasites still present in stool samples.

Ultimately, after treatment with albendazole twice daily and metronidazole three times daily for 3 weeks, the patient achieved resolution of giardiasis, as indicated by subsequent tests. This outcome supports the notion that combination therapy and prolonged treatment with metronidazole and albendazole are effective strategies for clearing refractory giardiasis.

6 Conclusion

Treatment failure in Giardia lamblia infection is characterized by the persistence of symptoms and the continued presence of parasites in stool samples. Current data to guide treatment in cases where nitroimidazole therapy has failed are limited. Combination therapy with two or more antigiardial drugs appears to be more effective than monotherapy in managing treatment-refractory cases. It is crucial to obtain molecular epidemiological evidence on the genetic variability of circulating G. lamblia isolates in instances of refractory giardiasis.

Our experience with this case suggests that dual therapy with metronidazole and albendazole, when administered for an extended duration, can be effective in treating refractory giardiasis. We recommend further studies to validate this approach, which could provide valuable evidence for updating treatment guidelines.

Author Contributions

Thomas Asfaw Atnafu: conceptualization, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, writing – review and editing. Abdurahim Wereka Usman: data curation, investigation, writing – original draft. Elham Sany Shemsu: conceptualization, writing – review and editing. Eskedar Ferdu Azerefegne: conceptualization, supervision, validation.

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to report.

Ethics Statement

The author's institution does not require ethical approval for the publication of single case report.

Consent

The patient has provided written informed consent for publication of the case.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this case report are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.