Complexities and opportunities: A review of the trajectory of fish farming in Zimbabwe

Abstract

Zimbabwe is currently rated as one of the top 10 fish producers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fish farming in Zimbabwe is dominated by the culture of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) followed by rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Over 90% of the cultured fish is O. niloticus, which comes from Lake Kariba. Since the first decade of the 21st century, there has been a significant increase in fish production from two tons to eight tons annually. The increase in fish production has been attributed to the government and donor-funded fishery programs. In this review, current practices, opportunities, and challenges for aquaculture in Zimbabwe are highlighted. The current practices include intensive, semi-intensive, and extensive aquaculture systems. Consistent high market demand for fish and numerous water bodies with potential for cage culture are some of the drivers for aquaculture. Despite the industry's significant growth, there are still a number of management and production issues that need to be resolved. Weaknesses in structural issues and operational frameworks in Non-Governmental Organizations, lack of credit facilities, subsidies, limited technology, obfuscated governance, weak fish disease surveillance mechanisms and legal frameworks, and constrained human resources capacity are some of the challenges plaguing fish culture in Zimbabwe. Cogent aquaculture policies, sustainable subsidies, intensive training of human resources and fisheries experts, strengthened disease surveillance, cheaper alternative fish feeds, reliable viable fingerling production, concerted value chain efforts, and exploration of lucrative export markets is a panacea for the fledgling aquaculture industry in Zimbabwe.

INTRODUCTION

The Republic of Zimbabwe is a landlocked country with a few perennial freshwater rivers [1]. Regardless, a large number of dams, numbering more than 12,000, have been built across the country over the years primarily to harness water for electricity generation, domestic use, livestock watering, and irrigation [2]. Most of these dams and other water bodies, all occupying a surface area of over 3910 km2, have been exploited for fisheries and fish farming [2]. Though there are some glaring fishery data gaps, the dams have positively influenced national fish production and play a significant role in ensuring food security and poverty alleviation for rural communities through income and employment generation [1, 3].

The concept of fish farming in Zimbabwe was introduced by colonial administrators as early as the 1950s with the aim to develop trout farming through stocking dams in the Vumba area [2, 4]. Up to around 1998, the development of the industry in Zimbabwe was slow [3]. The slow development is attributed to the fact that (i) the sector was initiated by foreign donors and (is still) dependent upon international finance, and (ii) the government did not support fish farming because they did not consider it as a major economic activity [1, 5]. Fish farming only started gaining prominence in Zimbabwe after Lake Harvest Aquaculture (Pvt) Ltd was granted a license by the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZPWMA) to produce Nile tilapia in cages in the eastern basin of Lake Kariba in 1997 [6, 7]. Since then a few fish farms have been established in Lake Kariba, Lake Chivero, and other small dams [7]. Available fishery statistics indicate that after the first decade of the 21st century, there was a tremendous increase in fish production from about two thousand tons per year to about eleven thousand tons per year [1, 8].

In 2017, the government initiated the Command Fisheries program aimed at enhancing food and nutrition security, creating employment opportunities, improving accessibility to fishery resources, and building the resilience of local communities against the effects of climate change [9, 10]. The program was largely driven by rural communities, mostly women and youth, at small-scale artisanal fishery levels [1]. In order to ensure sustainability of the Command Fisheries program, the Government of Zimbabwe partnered with the private sector and some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) [1]. The NGOs worked on the development of aquaculture and fisheries in low-lying rural and relatively underdeveloped remote areas of the country [11]. Arguably, with this support, the estimated fish production increased to about 10,700 tons per year in 2018 [1, 12]. Additionally, the establishment of community gardens models (which integrated horticulture and aquaculture) and the various dam construction projects up to date increased fish farming hotspots in the country that have the potential to commercialize their operations [13]. What has been lacking is an invaluable insight into the trends and trajectory of fish farming or aquaculture that can better examine the challenges and establish the opportunities for the blooming and potentially lucrative aquaculture sector in Zimbabwe [14]. This review aimed to discuss the (i) current practices, (ii) opportunities, and (iii) challenges of fish farming in Zimbabwe. The review seeks to answer the questions: (i) are there new aquaculture practices developed in Zimbabwe?, (ii) what are the opportunities for the fish farmers and downstream industries such as fish feed makers and hatchery manufacturers?, and iii) what are the challenges facing and hampering the growth, if any, of the aquaculture sector in Zimbabwe? The ultimate goal was to provide insights that may be useful for integration into the promulgation of the mooted National Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy of Zimbabwe.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used a constrained thematic analysis based on three aspects: current practices of aquaculture, opportunities, and challenges facing fish farming in Zimbabwe. Published journal articles, technical reports mainly from Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), and governmental compendiums on water, fisheries, and aquaculture as well as relevant traceable newspaper articles were used as credible sources of literature for the study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Size and the importance of fish farming in Zimbabwe

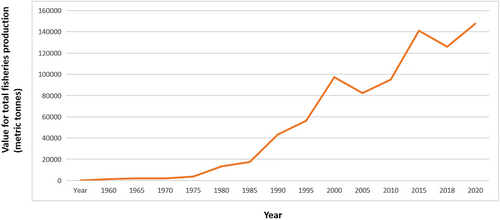

Zimbabwe has a relatively developed aquaculture sector and has been one of the top-10 fish farming countries in Sub-Saharan Africa for the last decade [1, 12]. The national potential demand for fish is estimated at 60,000 metric ton (MT) per year [12]. The total production is approximately 25,000 MT of which 15,000 MT comes from aquaculture and 10,000 MT from capture fisheries [1, 12]. Therefore, there is an estimated deficit of 35,000 MT [1, 10]. The deficit is satisfied through imports or increased supply [1]. Zimbabwe, on average, imported 9482 MT of fish per year between 2017 and 2020 [1, 10]. The bulk of Zimbabwe's imported aquaculture products originates from neighboring countries like South Africa, Mozambique, and Namibia [12]. South Africa is the main supplier of canned products (e.g., pilchards and sardines) that are widespread in the country's supermarkets [1]. Some of the canned fish products (e.g., tuna) come from as far as Thailand [1]. South Africa also supplies significant volumes of fish meal used for the production of livestock feeds in Zimbabwe [1]. Other fish products come from Namibia (e.g., horse mackerel and hake) see Sendall et al. [1]. Registered exports of fish products are dominated by fresh, chilled, and frozen tilapia, mainly from Lake Harvest Aquaculture (Pvt) Ltd [1, 12, 15]. The bulk of tilapia products are currently sold to the Southern African Development (SADC) regional market, with Zambia taking up the largest share ostensibly due to its close proximity to Zimbabwe through Lake Kariba [12]. Exporting of higher value products such as fresh fillets to the European Union still occurs, but to a lesser extent in recent years because of geopolitical hostilities between Zimbabwe and European countries [3]. As shown in Figure 1, the value for total fishery production (in metric tons) steadily increased from 1975, reached its peak in 2000, and decreased by 22% from 2000 to 2009. The value increased by 48% from 2010 to 2015 and decreased by 11% from 2015 to 2018. There was an 11% increase from 2018 to 2020 [16, 17].

Examining the dynamics of fish supply and demand size, it is cogent that there is a potential huge local market demand for fish products in Zimbabwe, which is currently filled up by relatively cheaper imports from neighboring SADC countries [1]. However, if all the country's 41 major reservoirs are fully utilized, there is potential to increase the output to 1.5 million tons of fish supporting the livelihoods, food security, and social well-being of 1.2 million people at the primary level [8].

According to Gono et al. [5] and FAO [12], the per capita consumption of fish and fish products for Zimbabwe was about 3.72 kg, which is relatively lower compared to, for instance, South Africa (15.4 kg) and Zambia (6.5 kg). The estimated total yearly fish consumption in 2017 was 50,497 MT with a commercial retail market value of US$132 million [8]. The yearly per capita consumption of fresh, frozen, and dried fish was 3.89 and 3.64 kg in rural and urban areas, respectively, which indicates that there is not much significant difference in fish consumption patterns among Zimbabweans [10, 13]. In a nutshell, the demand for fish in Zimbabwe is very low compared to other countries in the region with the average per capita fish consumption in Sub-Saharan Africa at about 8.9 kg [18]. Interestingly, the Sub-Saharan region's average per capita annual fish consumption figure is much lower than the 2023 global per capita consumption range of 19.2–20.5 kg [12]. This exposes that relatively, the Sub-Saharan African region, which is on average arid to semi-arid, has low fish production and consequently, the fish consumer patterns (although varying by countries) are generally low for the region [12]. The main drivers behind the low per capita fish consumption in the Sub-Saharan African region needs thorough examination in a different platform. Regardless, the low fish production and per capita fish consumption levels juxtaposed to the numerous freshwater bodies in Zimbabwe reveal a gap for the vertical growth of the aquaculture and wild capture fisheries industry [1]. What it entails is that policymakers have to be innovative and incentivize the entrance of new fish farmers into the fisheries sector and build a resilient value addition chain structure to sustain the existing fish farmers.

In terms of employment generation, about 4000 people are employed in the aquaculture sector with nearly 44,000 employed in the wild capture fisheries and its downstream industries in Zimbabwe [12, 15]. The largest aquaculture organization in Zimbabwe, that is, Lake Harvest Aquaculture (Pvt.) Ltd. Employs about 600 workers in its value chain operations [15]. The employment data for other smaller operators is presently unclear [1], but approximately, 3000 people are directly employed in wild capture fishery with thousands more employed in spin-off sectors such as trade, marketing, production, and processing equipment sales, fish feed, raw material supplies, net making, and boat maintenance and repairs [1, 12].

Fish (both farmed and wild-caught) are mainly sold in whole fresh state and frozen in Zimbabwe [1]. Tilapia is a very popular and well-favored species in Zimbabwe where it is widely known as ‘bream’ [1]. Comparatively, there is a strong preference for farmed tilapia over the wild-caught as the latter are perceived to have quality problems of off-flavors, spoilage, presentation, and traceability [1]. Tilapia, more particularly the farmed, are often processed into frozen fillets and are readily available in butcheries and supermarkets across the country [1, 10]. Fillet processing by-products, such as heads and belly flaps, are easily affordable to low-end consumers [8]. Trout, on the other hand, being a non-endemic species farmed only in the Eastern Highlands, is both less popular and more expensive than tilapia and is mainly available in upscale supermarkets and restaurants [1]. The range of trout products includes frozen whole trout, trout fillets, smoked trout, and trout pates [8].

There is an increasing demand for fingerlings, particularly tilapia as interest to develop grow-out farms continue to grow in recent years [19]. Fingerling production and marketing is increasingly becoming a lucrative business for the major commercial aquaculture players [1, 3, 15]. In general, there are about 4000 registered fish farmers and the main aquaculture hotspots include the hot and arid Lowveld, the northern part of Zimbabwe and some cold parts of the Eastern Highlands [1].

Common cultured fish species opportunities and challenges for their culture in Zimbabwe

Fish farming in Zimbabwe is still relatively a small industry with only a few commercial farms in existence [7]. The Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are the two main farmed species with the former being the sub-sector's mainstay [1, 2]. A big advantage of tilapia rearing is that they can tolerate low quality water with low amounts of dissolved oxygen compared to other fish species [2, 20]. The Nile tilapia was introduced to Zimbabwe in the 1970s and 1980s from Kenya, Zambia, and Scotland (through the University of Sterling) for fish farming purposes [2]. This exotic fish species has successfully invaded almost all water bodies in Zimbabwe with devastating consequences on the local indigenous and endemic species. Trout, on the other hand, was introduced into Zimbabwe's Eastern Highlands from Europe in the early 1950s solely for the purpose of recreational fishing [2, 3]. While the warm water temperatures (above 24oC) of northern Zimbabwe are conducive for tilapia cultivation, the cooler temperatures in the eastern highlands are suitable for trout production. The government has a trout hatchery in Nyanga in the Eastern Highlands where colder temperatures enable trout production. Both species are farmed on a commercial scale, but trout is both less popular and more expensive than tilapia.

An experiment was tried in Lake Manyame (Darwendale Dam) to culture the common carp for the biological purpose of controlling weed growth with relatively little success from 1997 to 2008. Further trials to culture the species afterward were a failure as the water was becoming more polluted from the upstream urbanized Upper Manyame sub catchment [2]. Recently, the newly introduced Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources has introduced experiments of Sharptooth African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) culture in its various research stations dotted across Zimbabwe [21]. Intensive training in African catfish production has been held and there is commendable hatching success in the ponds stocked with African catfish across the country (MLAFWR, 2021). While it is largely expected that the African catfish will be successful and proliferate in ponds across the country; no attention has been paid to the size of the market demand for the species in a religiously conservative country such as Zimbabwe where its consumption is traditionally low mainly because of ‘frivolous’ religious, cultural, and superstitious beliefs [1].

Fingerlings are mainly for own on-farm use; they are rarely sold to other farmers for a variety of reasons, including that the species is not permitted to be taken beyond the Zambezi Valley [1, 3]. Hybridization of O. niloticus with O. mossambicus and O. mortimeri in the Lake Kariba hatcheries has been successful with the species closely related with regard to productivity, appearance and even culinary flavor [1, 3]. There are more than six large commercial fish farms with their own hatcheries in Zimbabwe [1, 10]. These include Lake Harvest Aquaculture (Pvt) Ltd, The Bream Farm, Mazvikadei Fish Farm, Clairmont Trout Farm, and The Trout Farm, Ruparara Trout Farm [1, 10]. Nonetheless, there are other fish farms that are relatively small in size developed by individual farmers or with donor support, for example, the ongoing World Vision EC Fisheries Project with rudimentary only for the farm hatcheries [1, 10]. Nearly, 75% of the fish farms in Zimbabwe produce their own seed (fingerlings) while about 14% comprising mainly trout farms, depend on the ZPWMA for fingerlings [1, 8]. Fingerling production is delicate and more so the transportation from hatcheries to the ponds needs special training and oxygenated equipment [8]. This delicacy restricts the transportation distances of fingerlings from hatcheries to areas of demand limiting productivity of small fledgling fish farmers as there is poor seed [12].

Fish breeding technologies

Zimbabwe has the genetically improved farmed tilapia (GIFT), which was acquired from the United States of America by Lake Harvest Aquaculture initially as an experiment but escaped into Lake Kariba and its fingerlings have been widely distributed across the country [15]. The GIFT is a strain of tilapia produced through classical selective breeding methods over a period of more than 30 years. Selective breeding is the process of choosing the parents of the next generation in such a way that it will result in improved performance for certain traits considered important during production and marketing [22]. These genetic gains are cumulative and permanent. With classical selectivity, there is no genetic manipulation but nature selects the best traits that are then utilized by scientists to optimize biological production and survival of a species [22].

In the GIFT method, full-sibling families of fish are reared in small, separate enclosures until they are big enough to be tagged with a microchip and moved into a communal pond. The tags allow researchers to identify individual fish and track their growth against their siblings and other individuals. Selective breeding is based on the assumption that fish are fecund animals meaning they can produce many offspring from a single female. This biological trait is exploited in the breeding programs through higher selection intensities enabling more rapid genetic improvement. In fact, the high fecundity of fish allows an improved strain to be multiplied and scaled out quickly to farmers. However, it is largely debatable on the margins that GIFT tilapia has increased tilapia culture production in the country. Another technology that is gaining traction is the YY male tilapia technology based on the genetic manipulation of sex [12]. This is the most successful sex reversal program which has had a significant economic impact on tilapia culture [23]. The YY male tilapia technology is based on the genetic manipulation of sex [12, 23]. This is achieved through a combination of feminization and progeny testing to identify the novel YY genotype that sires only XY natural male progeny or natural male tilapia. The process basically involves producing YY male, from YY male and YY females strain which is mated against a natural XY males and XX female fish lines. Then the pure YY is mated against a natural female XY to produce YY strain [23]. No sex reversal hormones are used in the process besides genetic manipulation to enhance rapid accelerated growth rates and this is assumed to make the fish safe for consumption [24]. However, the prohibitive costs of purchasing and maintaining genetic breeding equipment and the high price of the YY fingerlings make them expensive for most small-scale fish farmers in developing nations like Zimbabwe [12].

In Zimbabwe, the YY-tilapia males based on O. niloticus are being cultured at Lake Harvest [15]. However, the company has yet to release the fingerlings of the YY-tilapia to the rest of the fish farmers in Zimbabwe. The other method that is used for sex reversal is hormone treatment mainly by the 17-α MT hormone in producing a mono male sex population in O. niloticus fry under tropical conditions in ponds in Zimbabwe [25]. However, most European countries do not accept tilapias that have been subjected to hormonal treatment because there may be health implications when people consume these fish [14]. However, it is reported that the use of MT hormone in food producing animals could be accumulated in environment and aquatic animals [24]. The MT hormone residue would cause a harmful effect to animals and human health, such as hepatotoxic effects, early pregnant reaction, and fetal anomaly [24].

Fish production systems in Zimbabwe

Aquaculture production is often classified in terms of intensity and scale of production into extensive, semi-intensive, or intensive productive systems although the limits in real time classification are rather blurred in geocontexts (sea, river, dam, lake, ponds, raceways, etc.) marine, brackish, and freshwater system dynamics [8]. Fish farming is carried out on industrial, commercial, and subsistence levels in Zimbabwe, with the largest production emanating from Lake Harvest Aquaculture in Lake Kariba [3, 15]. Lake Harvest Aquaculture is an intensive vertically integrated fish farm encompassing each stage of production in the value addition chain whereby input levels are high and the feed is commercial and stocking density in triple net floating cages is high [1, 15]. The use of triple net floating cages in Lake Harvest has resulted in the commercial production evolving from 100 tons in 1996 to 10,200 tons in 2012 to 22,000 tons in 2021 and produces fish for domestic consumption and exports [1, 15, 26]. Contrary to intensive aquaculture practiced at Lake Harvest, which requires high investment, semi-intensive aquaculture is practiced mainly by fishery cooperatives and the rural communities and few individual fish farmers in Zimbabwe [1, 8].

These small-scale farmers rely both on natural food production in the ponds and on supplementary feed, usually from locally available plants or agriculture by-products [27-29]. The farmers also fertilize their ponds by manure and inorganic fertilizers [30]. In extensive aquaculture, the inputs are low and the fish primarily feed on food algae and zooplankton that grows in the water body [8, 28]. Many individual farmers in Zimbabwe who take fish farming as part-time activity are in this category [1]. Stocking rates are typically low, there is little or no supplemental feed offered to the fish but low levels of fertilization in the form of manure may be applied to the ponds and household members usually manage the ponds [1]. These farms generally do not require large capital for running and there is little amount of technical input into the production [1]. This small-scale system tends to be rural, and most of the fish are consumed by the family or sold on the pond bank [1, 31].

Opportunities for aquaculture research, education, training, and technical assistance

To improve the aquaculture sector with human resources and skills capacity, the state universities in Zimbabwe, including the University of Zimbabwe, Chinhoyi University of Technology, Lupane State University, Marondera University of Agriculture Sciences and Technology, Midlands State University and the Great Zimbabwe University, conduct research and are directly involved in the training of personnel in aquaculture, aquatic ecology, and fisheries, wildlife, agribusiness, and related subjects at undergraduate and postgraduate degree levels. The ZPWMA has research stations scattered in various parts of the country, including the Lake Kariba Fisheries Research Institute, Lake Chivero Fisheries Research Station, Sebakwe Fisheries Research Station, Lake Mutirikwi Fisheries Research Station, Makoholi Research Institute, Matobo Fisheries Research Station, and Nyanga Trout Research Center. Also, the Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water, Climate, and Rural Development undertake aquaculture and fisheries management research at Henderson and Matopos Research Station [21]. Demand-driven short training courses on aquaculture, fish disease detection, water quality analysis, pond construction, repair and maintenance, fish feed formulation, fish disease treatment, fingerling collection, and transportation are ongoing on a regular basis, offered by private players and the public universities, and in some cases are donor funded notably the IOC-SmartFish Program short training courses on “Aquaculture as a Business” and on “Fish Handling and Quality Control” [21].

The World Vision Zimbabwe and its partners also offer some training courses on aquaculture under its EC Fisheries Project in Chivi Rural District, Mwenezi, Rutenga, Masvingo, Chipinge, Nyanga, and Beitbridge Districts with primary and high schools benefiting under the ‘One pond, One School’ project [21]. The impact has caused a relative increase in awareness, technical skills, and food security and nutrition especially for vulnerable children in rural impoverished areas in Zimbabwe [1]. Agriculture Extension officers also offer minimal training and extension services on rural aquaculture development [8]. Ongoing research involves feed trials and research on potentially cultivable indigenous tilapia species and the African catfish [21]. While commendable, the impact of fisheries and aquaculture training has not yet been drastic on fish production levels in the country and there remains a modicum to introduce community aquaculture training and monitoring extension services [21]. Of note is the extent of the impact of research and extension on the sustainability and efficiency of the value addition chain in the aquaculture sector [1].

Constraints faced by the fish farming industry in Zimbabwe

Despite the massive investment in dams and the support rendered by various stakeholders, the fish farming sector has been confronted by various challenges [1]. It is worth noting that fish farming in Zimbabwe is mainly spearheaded by NGOs and the implementation of fish farming has been incapacitated by limited funding from the donor community [21]. The donor agencies have failed to adequately fund local NGOs resulting in the selective implementation of fish farming projects as some communities are left marginalized [1, 12, 21, 32]. Furthermore, there are challenges emanating from high-level bureaucracy in the donor community, which requires strong accountability to boards of directors and government ministries that release funding [11]. Moreover, some NGOs do not make a follow-up after initiating fish farming projects thus leaving the prospective fish farmer with a burden to manage the projects on their own mostly leading to their collapse [10].

After harvesting, fish farmers face transport challenges to sell their produce [1, 8]. It is important to note that fish is a highly perishable commodity, so any delay in reaching the market can be disastrous [1]. Fish farmers resort to selling their fish harvest to proximal individuals, normally local shops and middlemen, at low prices thus prejudicing and discouraging them as fish farming is arduous and a risky venture [1]. Guaranteed, consistent, and reliable fish supply is a hard condition to fulfill for most fish farmers as supermarkets want to be assured that fish supply is reliable and therefore growing their market beyond their immediate surroundings [1]. Moreover, most of the fish farmers have little knowledge about the market supply and demand dynamics resulting in unscrupulous business people exploiting them by offering lower prices [1]. Failure to obtain ready markets has constrained fish farmers to expand into a more commercialized business; hence, they remain at subsistence level [10]. More importantly, inadequate supply of quality feed and seed fish has been a long-standing hindrance to the growth of aquaculture [1, 15].

Many fish farmers, particularly the rural folk lack credit facilities to finance labor and technologies [1]. Most of the fish farmers lack collateral security to solicit loans from local banks [11]. The lack of borrowing power often exposes rural people to a donor dependency syndrome [10]. The trends in the technological environment, globally, require organizations to adopt and cope with a wave of transformation which can improve the viability and profit margins of a business [8]. In this regard, most fish farmers in Zimbabwe lack suitable fish farming technology, proper storage facilities, and proper use of medicines, hatchery, and improved fish feeds among others [1]. This reduces the opportunity of fish farming to flourish into a more commercialized sector [11].

Though the government is playing a critical role in the development of fish farming, its fragmentation is proving to be an obstacle in the enhancement of aquaculture [3]. Different departments are mandated to implement pieces of legislation that are relevant to aquaculture and fisheries [33]. This inevitably leads to lack of coordination resulting in poor performance of the aquaculture sector [33]. For example, the responsibility for the conservation and management of water bodies includes capture and recreational fisheries and lies with the National Parks and Wildlife Authority of the Ministry of Environment, while the responsibility for aquaculture rests with the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Resettlement [33]. This creates problems for fish farming development [33]. However, the recent incorporation of fisheries and aquatic resources under the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Water, Fisheries and Rural Resettlement has been a positive first step in providing such an enabling policy framework [21].

It has been noted that most of the training received by fish farmers have been done for the sake of training without some important understanding of the key technical skills required in fish farming [10, 14]. In fact, there appears to be greater interest in receiving certificates than producing fish among the farmers [14]. The basic technical skills to successfully run a fish farm include the knowledge of water quality, pond design, basic fish husbandry practices, disease identification and treatment, and development of business plans. Technical knowledge of the above mentioned factors for freshwater aquaculture is lacking in Zimbabwe.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Zimbabwe holds an estimated 60% of all dammed water in Southern Africa and is home to the largest freshwater fish farm (Lake Harvest Aquaculture (Pvt) Ltd) in Africa. Nonetheless, less than 5% of the 400,000 ha suitable for inland aquaculture is currently being utilized for fish production [21]. Government and relevant stakeholders should provide support to fish farmers in vulnerable provinces where freshwater is abundant in order to generate employment and promote food security in such regions. The support entails linking small farmers to local, urban, regional, and global markets, increasing rural extension programs to educate farmers and enhance their capacities to adopt new aquaculture technologies [1]. The government and other stakeholders should embark on the progressive rehabilitation of small dams. Small dam rehabilitation is essential in supplementing water supplies and promoting fish farming as some districts such as Mwenezi, Chivi, and Chiredzi are arid [11].

Extension services must be provided on water quality through workshops for fish farmers. These workshops must provide hands-on experience for instance on how to test and interpret water quality as well as the measures to take to maintain a good water environment for fish growth. Fish feed formulation and production are a vital area of interest where private businesses can invest because until now Zimbabwe has only three recognized fish feed companies which produce below the needed quantity of fish feed [1]. It is greatly appreciated that NGOs have done quite well in supporting fish farmers in the form of inputs and infrastructure. However, it is recommended that these development agencies should not promote a dependency syndrome since it paralyzes local community projects [10]. Instead, these donor agencies should assist the locals to shift and adapt their mentality progressively from dependency to self-sustenance. Fish farmers are encouraged to adopt an integrated fish farming approach where the waste from crops and livestock such as maize bran, chicken and pig manure, and cow dung is used to feed fish and vice versa [28].

Considerable resources and time have been spent on constructing fish ponds, providing feed, and fingerlings for farmers who have no training on how to manage a fish farm, particularly biosecurity measures [1]. Biosecurity measures should be adopted in fish farms with strategies to prevent and control disease incidences and spread [1]. Currently, Zimbabwe does not have an approved fish disease diagnostic center, which may prove to be disastrous in the event of a disease outbreak [1]. Hence a fish disease diagnostic center should be established which will respond to any fish disease outbreak. Fish farmers in the rural areas should not treat fish culture as a side activity or hobby but as a commercial activity that has the potential to turn around their lifestyles [10]. Their perception has to change if they want to move from being subsistence to commercial producers such as Lake Harvest Aquaculture (Pvt) Ltd. Most fish farmers are currently selling their produce to locals buying for resale. However, it is recommended that they enter into even bigger contracts with large retail supermarkets such as Thomas Meikles and OK [1]. These large retailers buy fish in bulk for resale and thus fish farmers can form consortiums to bargain and gain some financial security. The bottom line is that the government must craft a cogent National Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy in Zimbabwe that clearly sets out the roles of agencies, NGOs, ZIMPARKS, farmers, and other downstream players to guarantee sustained growth for the aquaculture industry in the country.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Nyasha Mabika: Conceptualization; Data acquisition; Data analysis and interpretation; first draft; manuscript revision; final approval. Beaven Utete: Data acquisition; Data analysis and interpretation; manuscript revision; final approval.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no acknowledgments to mention.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Since the study did not involve the use of animals or humans, no ethical approval was required.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study is available on request from the corresponding author.