Oral stereotypic behaviors in farm animals and their causes

Abstract

High stocking density and suboptimal conditions limit animal behaviors in modern livestock farming. This is particularly evident in captive animals, in which the motivation for foraging behavior is often thwarted. Oral stereotypic behaviors are common in farm animals. Ruminants (e.g., cattle and sheep) show oral stereotypic behaviors such as tongue-rolling, self-sucking, and inter-sucking. Captive pigs exhibit oral stereotypic behaviors such as bar-biting, sham-chewing, and ear-biting. Chickens peck at drinkers, feeders, and pens. Stereotypic behavior in livestock can be reduced by selecting a specific diet composition that prolongs their eating time and increases their satiety. Furthermore, reducing stocking density and enriching the farming environment encourage livestock to explore and reduce stereotypic behavior. It is important to note that stereotypic behavior is also influenced by organismal physiology. Stereotypic behavior was considered an indicator of poor animal welfare. However, recent research has revealed that animals engage in stereotypic behavior as a response to external stimuli, aiming to alleviate the negative impact of these stimuli on their well-being. Animals that frequently show stereotypic behavior may have higher levels of stress. Certain stress indicators also affect the expression of stereotypic behavior, such as 5-hydroxytryptamine and dopamine. Consequently, further investigation is necessary to understand how stereotypic behaviors affect the physiological state and metabolic processes of animals. This paper discusses the research progress on the oral stereotypic behaviors of farm animals. The objective is to establish a foundation for enhancing livestock feeding conditions and optimizing feeding practices, ultimately reducing stereotypic behaviors.

INTRODUCTION

As early as 1983, under the initiative of the Commission of the European Communities, a group of experts in Brussels proposed a definition of stereotypic behaviors [1], which are fixed in form and orientation and serve no obvious function. This is specifically defined as repetitive, seemingly non-functional behaviors in a wide range of animals, including farm animals, companion animals, and laboratory animals [2-6]. Stereotypic behavior has also been observed in zoos, such as in captive polar bears. Factors such as environmental richness, seasonal changes, and visitor density can influence polar bear activity [7]. Although increasing environmental enrichment may reduce stereotypic behaviors in both farm and zoo animals, complete elimination is not always achieved [8]. For instance, even in the environmentally rich wild, lemon sharks have been observed to exhibit stereotypic swimming movements [9]. Additionally, feeding management, diet composition, neuroendocrine networks, and animals' personality may also contribute to stereotypic behaviors [10].

The intensification of modern agriculture has resulted in the imposition of limitations on the natural behavior and feeding patterns of animals, with the aim of achieving greater economic efficiency; for example, restricted feed intake during the pregnancy stage of sow [11] and farrowing crates to restrict the activities of sow [12]. The “five freedoms” of animal welfare have a provision for “Freedom to express normal behavior,” meaning “by providing sufficient space, proper facilities, and company of the animal's own kind” [13]. The above farming practices are against animal welfare regulations. In instances where animal welfare conditions are substandard, animals may experience stress.

Stereotypic behaviors in animals tend to occur the most in suboptimal environments [14]. Webb et al. [2] suggested that stereotypic behaviors are associated with negative emotional states and poor health, which have long been considered signs of poor animal welfare [15-17]. The failure to meet the behavioral and nutritional needs of animals in intensive farming can lead to the development of stereotypic behaviors [18]. Prolonged engagement in stereotypic behaviors can result in compromised physical well-being and perturbations in the animal's metabolic processes [19]. In recent years, another view has emerged that stereotypic behaviors may be a way for animals to cope with unfavorable environments, known as the “coping hypothesis” [20]. The fact that animals express stereotypic behaviors as a way of coping with discomfort may be beneficial; for example, striped mice that express stereotypic behaviors have higher reproductive performance [21], and the milk yields of stereotypic cows are higher than that of normal cows [22]. However, this does not mean that stereotypic animals have better welfare. This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the factors that influence oral stereotypic behaviors in farm animals and proposes interventions to reduce stereotypes in different animal species. Its aim is to serve as a valuable resource for enhancing livestock farming practices and promoting the welfare of farm animals.

PREVALENCE OF STEREOTYPIC ORAL BEHAVIOR

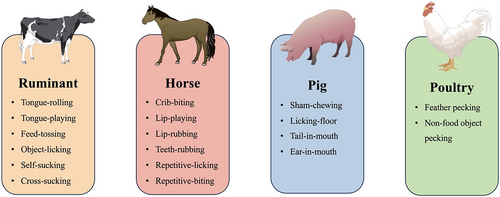

Farm animals include pigs, dairy cows, beef cattle, goats, poultry, horses, rabbits, etc. However, studies on stereotypic behaviors have mainly focused on cows, horses, and pigs. The most common oral stereotypic behaviors of these animals are displayed in Figure 1 and specifically described in Table 1. Oral stereotypic behaviors are common in farm animals and occur at every stage of life [23, 24]. Oral stereotypic behaviors found in dairy or beef cattle farming include tongue-rolling, feed-tossing, self-sucking, and inter-sucking. However, most studies on oral stereotypic behaviors in cattle had focused on tongue-rolling. In a recent observational trial on dairy cows, tongue-rolling was found to occur in 29% of cows and was more prevalent in Jersey cows than in Jersey–Holstein crosses [24]. In contrast, in the study of Binev [25], tongue-rolling was present in only 4.4% of dairy cows. In another observation on feed-tossing behavior of dairy cows, it was found that 37.8% (68/180) of the dairy cows had feed-tossing behavior [26]. Horses are other farm animals that often exhibit stereotypic behaviors. 65% of horses in a French behavioral observation trial exhibited stereotypic behaviors such as repetitive trough-licking, head-shaking and nodding, lip-playing, repetitive object-biting, repetitive wall-licking, lip- or teeth-rubbing, etc. [20]. Crib-biting behavior is the most common stereotypic behaviors in horses [27], and in several observational trials of crib-biting behaviors in adult horses, the prevalence of crib-biting ranged from 0% to 13.3% [28-30]. In all of these observations, crib-biting was found to be more prevalent in thoroughbreds than in other breeds, which is consistent with the findings of Robbins et al. [24]. This also suggests that genetic factors may contribute to the occurrence of stereotypic behaviors. Oral stereotypic behavior has also been observed in pigs in several studies. In the tethered mode, sham-chewing behavior was present in 10% of sows [31]; in pregnant sows, the occurrence of stereotypic behavior decreased with the progression of gestation [4].

The most common stereotypic oral behaviors of different farm animals.

| Behaviors | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pigs | ||

| Sham-chewing | The pig will keep chewing, but there is no visible food in the mouth | [133] |

| Licking-floor | The pig touches the floor with its tongue and moves its head with it | [133] |

| Tail-in-mouth/ear-in-mouth | The pig sticks their mates' tails or ears in their mouth | [94] |

| Dairy cows | ||

| Tongue-rolling or tongue-playing | The cow's tongue makes repeated circular movements inside or outside the mouth | [24] |

| Feed-tossing | The cow picks up a mouthful of feed and throws it into the air | [26] |

| Object-licking or pica | The cow licks or bites non-food objects (e.g., fences, food trough) | [134] |

| Self-sucking or inter-sucking | The calf sucks on their own or other calves' body parts | [62] |

| Horses | ||

| Crib-biting | The horse grasps a fixed object with its incisors, pulls back and draws air into its esophagus while emitting a characteristic pharyngeal grunt | [20] |

| Lip-playing | The horse moves its upper lip up and down without making contact with an object, or the horse smacks its lips together | [20] |

| Tongue-playing | The horse sticks out its tongue and twists it in the air | [20] |

| Lip- or teeth-rubbing | The horse rubs its upper lip or its upper teeth repetitively against the box wall | [20] |

| Repetitive-licking/biting | The horse licks or bites the box walls, box grids, or external part of the feeding trough | [20] |

| Poultry (especially chickens) | ||

| Feather pecking | One bird used its beak to grasp and pull the feather of another bird. A feather can be from any area of the bird's body except the wing | [135] |

| Non-food object pecking | One bird used its beak to peck at the feeder, drinker, pen wall and other non-food objects in the pen, and performed in a stereotypic manner | [96, 135] |

CAUSES OF ORAL STEREOTYPIC BEHAVIORS

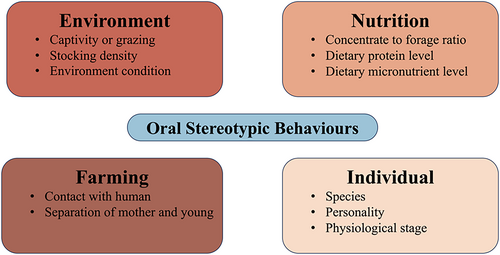

Researchers have long sought to understand the causes of oral stereotypic behaviors in animals. The incidence of stereotypic behaviors when animals are grazed is significantly less than when they are kept in captivity [32], or even if stereotypic behaviors do not exist [33], the difference between captivity and grazing may be the cause of animals expressing stereotypic behaviors, such as food source, number of animals in the group, space for activities, contact with humans, harsh environment (e.g., noise, bright light) [34], etc. A distinctive feature of captive animals is that they are restricted in the amount and composition of their food intake, which allows the farmer to reap higher economic benefits. Restricted feeding measures go against the animals' natural foraging patterns, and the animals' motivation to eat is thwarted [35] and they may target objects in the enclosure or their companions for foraging. Stereotypic behaviors resulting from restricted feeding have been found in cattle, pigs, and poultry [11, 36, 37]. Another distinctive feature of captive animals is that food is entirely human-provided, which also makes for short feeding time, with animals often completing the entire feeding process within a few minutes. Similarly, this allows the animal's motivation to eat to be underexpressed. Commonly, farm animals live in herds in the wild. In contrast, some animals are kept in small groups or even individually in captivity, such as newborn calves and rabbits. Prolonged rearing in small groups or individually can lead to the development of stereotypic behaviors in animals. Individually reared calves have been reported to express more tongue-rolling behavior and spend less time eating, exploring, and moving around than group reared calves [38]. Non-human primates raised in groups also have less stereotypic behavior than those raised individually [39]. The reason for this may be the lack of social interaction when animals are kept alone, and the increased boredom of animals leading to stereotypic behaviors. However, for some animals that are solitary in the wild, group rearing leads to an increase in stereotypic behaviors, such as the captive Felis chaus [34]. For most farm animals, activity space can be understood as feeding space or enclosure space. However, sometimes animals are kept in tiny holding spaces. They are unable to turn around or make movements of greater amplitude, such as in gestating sows [40], thus limiting the behavioral needs of the animals, while increasing the holding space of the animals or decreasing the density of the holding reduces stereotypic behaviors of the animals [41]. Captive animals will have more frequent contact with humans compared to wild animals, which may increase the animals' fear. It has been shown that animals in zoos exhibit more stereotypic behaviors as the density of visitors increases [42, 43]. The above reasons can be summarized as frustrated motivation, fear, and physical discomfort leading to stereotypic behaviors [44]. In addition to this, age [25], deficiency of the trace element manganese [45], and premature separation of mothers and young animals can lead to the occurrence of stereotypic behaviors. In summary, the possible causes of oral stereotypic behaviors expressed by animals are summarized in Figure 2.

Factors influencing animals to express stereotypic behaviors.

ORAL STEREOTYPIC BEHAVIORS OF FARM ANIMALS

Ruminants

With changing consumer demands, the demand for milk and beef has considerably increased in the past few years, promoting a greater degree of intensification of dairy and beef cattle farming. Intensive farming means a lack of grazing and restricted space for cattle, which leads to stereotypic behaviors [38]. Stereotypic behaviors are observed in calves, fattening bulls, and dairy cows [38] and are more prevalent in tie stalls and indoor cattle farms [46]. One of the most common forms of stereotypic behavior in cattle is tongue-rolling [25], which involves repeatedly turning and extending the tongue outside or inside the open mouth [2]. Tongue-rolling occurs at all stages of growth in cows [47] and is one of the non-nutritive oral behaviors (NNOB). In addition, NNOB also includes licking or biting fixtures.

It has been shown in studies over the last few decades that feeding time and rumination time of ruminants are influenced by the composition of the diet [48]. On the one hand, the more concentrate in the diet, the less time the ruminant spends on feeding and rumination [49], and reduced feeding and rumination time is one of the reasons for NNOB in ruminants [3]. On the other hand, too much concentrate causes a decrease in rumen pH [50, 51], which may cause rumen discomfort. Rumen discomfort is also one of the reasons for NNOB [3]. Furthermore, rumen discomfort is exacerbated by low salivary secretion due to insufficient feeding and rumination time. Interestingly, NNOB can be alleviated by changing the formulation of the diet (including roughage ratio). The effects of diet composition on oral behaviors of cattle (including dairy cattle, beef cattle, and calves) over the last 10 years are summarized in Table 2. From Table 2, it is clear that increasing the roughage content in the diet or increasing the length of feed can reduce NNOB and increase favorable oral behaviors in cattle. The reason for this is that increasing roughage content and roughage length in ruminant diets increases the feeding and ruminating time of ruminants [52, 52, 54], and when roughage is short, the stimulating effect on ruminants is reduced [55]. Therefore, oral behaviors of cattle can be improved by changing the composition of the diet. However, in a recent study, there were different results. Downey and Tucker [23] concluded that offering hay to 0–7 weeks calves did not affect calves' oral stereotypic behaviors performances 1 year later. We may be able to deduce that providing hay or increasing roughage content may only be able to reduce oral stereotypic behaviors in cattle in the short term, without having a long-term effect.

| Area | Cattle type | Diets | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida, America | Calves | Access to hay | Duration of non-nutritive sucking decreased by 24% compared to no access to hay | [136] |

| Isfahan, Iran | Calves | Barley grain or corn grain with alfalfa hay or corn silage | Duration of NNOBa decreased by 3%–37.8% compared to barley grain or corn grain without forage supplement | [137] |

| Guissona, Spain | Holstein bulls | Concentrate mealb with straw | Times of NNOB decreased by 61.5% over feed without straw | [138] |

| Concentrate pelletc with straw | Times of NNOB decreased by 50% over feed without straw | |||

| Kemptville, Canada | Calves | Larger chopped grass (3–4 cm) | Duration of NNOB decreased by 30.4% than ground hay (2 mm) | [139] |

| Caldes de Montbui, Spain | Calves | Diet with alfalfa hay | Duration of NNOB decreased by 39.3% over common diet | [140] |

| Diet with rye-grass hay | Duration of NNOB decreased by 32.2% over common diet | |||

| Diet with triticale silage | Duration of NNOB decreased by 44.5% over common diet |

- a NNOB = non-nutritive oral behavior.

- b Meal = concentrate presentation form was meal.

- c Pellet = concentrate presentation form was pellet.

We know that the movement of the tongue promotes the production of saliva in the mouth. For cows, saliva is weakly alkaline. Stereotypic behaviors associated with tongue movements (e.g., tongue-rolling and tongue-playing) may be a way for cows to alleviate excessive rumen acidity. It was reported that rumen pH was significantly lower in cows with tongue-rolling behavior than in normal cows fed the same ration [22]. This also reflects the mitigating function of tongue-rolling.

Sheep are also a common ruminant animal and often display stereotypic behaviors such as bar-biting and slat-chewing when kept in farms [56]. Like cattle, sheep are susceptible to oral stereotypic behaviors when they have limited feeding and rumination time. Particularly, when they are underfed or have a high-concentrate diet, sheep might express wool-biting [57]. However, less research has been conducted in recent years on diet and stereotypic behaviors in sheep. In a study by Vasseur et al. [57], the addition of barley straw to diets significantly reduced wool-biting behavior in sheep (p < 0.001). Inability to obtain colostrum by sucking the teat, which is also stressful for calves, but may only be stressful for the first 8–10 weeks [58]. This can lead to moodiness or stress in calves [59], then inter-sucking may occur. It can be speculated that the use of a bottle with artificial teat may be able to reduce inter-sucking behavior in calves. In addition, sucking behavior in calves is stimulated with lactose intake and continues after milk feeding [60], while the NNOB, including inter-sucking behavior, is reduced when feeding milk through a teat [61]. In a study by Salter et al. [62], they found that slowing the milk flow rate in the teat was most effective in reducing inter-sucking in calves.

In addition to this, there are many other reasons which can lead to inter-sucking, such as breeds. In a study by Ahmed et al. [63], it was found that cows had higher rates of both self-sucking and inter-sucking than buffaloes. The investigation reported by Lidfors and Isberg [64] also illustrated that the prevalence of self-sucking and inter-sucking differed between breeds of cattle. Diet changes can also reduce the rate of self-sucking in ruminants, and in a study by Martínez-de la Puente et al. [65], the addition of wheat straw to a regular diet reduced the rate of self-sucking in dairy goats. Nowadays, methods, such as tongue piercing [66] and tongue reshaping [67], have emerged that can prevent cattle from self-sucking. Regardless of the type of surgery, cattle show signs of mild bleeding after surgery. Three (tongue reshaping) or six (tongue piercing) months after surgery, self-sucking of cows disappeared. Even though these surgical methods can reduce self-sucking behavior in cattle, this surgical procedure is painful for animals. Painful surgical procedures are more inconsistent with animal welfare guidelines than stereotypic behaviors. Therefore, we don't recommend surgical methods to reduce stereotypic behaviors in animals.

Pigs

Domestic pigs were domesticated from wild boars over 9000 years ago [68], but still retain some of their ancestral behaviors [69], such as rooting and nosing at the ground. Under natural conditions, pigs spend most of the day foraging; however, in intensive farming, the diets are usually consumed by pigs within minutes [70], but pigs still maintain a high motivation to forage, leading to stereotypic behaviors, mainly sham-chewing [4, 71].

Studies on changing diet formulations to reduce stereotypic behavior in pigs over the last 10 years are summarized in Table 3. From Table 3, it is clear that increasing the crude fiber content of pig diets can reduce the sham-chewing and licking ground. It has been shown that fiber can promote satiety signals by facilitating chewing and salivation [72], and the volumetric effect of dietary fiber entering the stomach and combining with water can also fill the digestive tract [73]. Therefore, increasing the fiber content in the diet can be interpreted as increasing satiety and thus reducing oral stereotypic behaviors in pigs [71]. In a study by Oelke et al. [74], it was also found that stereotypic behaviors, especially trough-licking, floor-rubbing, and bar-biting, decreased with increasing dietary fiber in the diet. In addition to this, a common feature in most of the studies was that pigs exhibited stereotypic behaviors for a longer period before feeding, while oral stereotypic behaviors were reduced after feeding. Therefore, it can be suggested that as satiety increases (which can also be interpreted as a decrease in hunger), the oral stereotypic behaviors of pigs decrease.

| Area | Pig type | Diets | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hillsborough, Northern Ireland | Finishing pigs | 15.5% crude protein | Duration of tail-in-mouth decreased compared with 13.5% crude protein | [94] |

| Pirassununga, Brazil | Pregnant gilts | High fiber | Duration of sham-chewing decreased compared with low fiber | [133] |

| Shanghai, China | Pregnant sows | 7.5% crude fiber | Duration of total stereotypic behavior decreased by 68.8% over 2.5% crude fiber | [141] |

| Itaqui, Brazil | Pregnant sows from 74 to 102 days | 28.2% total dietary fiber | Times of trough licking, floor licking, floor snout rubbing, bar-biting, sham chewing decreased compared with 15.6% or 22.3% total dietary fiber | [74] |

| Wageningen, Netherlands | Piglets | Normal crude protein | Times of tail biting and ear biting decreased compared with low protein | [80] |

| Wageningen, Netherlands | Adult female pigs | High fiber diet | Duration of stereotypic chewing decreased | [142] |

Besides fiber, other nutrients can also modify stereotypic behaviors in pigs, such as protein. When dietary protein is insufficient, it stimulates protein leverage (pigs will regulate protein intake by overeating protein-diluting diets) [75], and if protein intake is consistently insufficient, pigs may shift their targets to their companions [76], so stereotypic behaviors such as ear-biting and tail-biting will occur. Some researchers have suggested that stereotypic or abnormal behaviors in pigs is due to insufficient protein in the diet. In other words, there is actually a deficiency or imbalance of amino acids in the diet [77, 78], because many brain neurotransmitters are synthesized from specific amino acids; for example, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is synthesized from tryptophan. Ursinus et al. [79] found that pigs with tail-biting behavior had lower levels of 5-HT in both platelets and whole blood than pigs without tail-biting behavior. Furthermore, in a study by Meer et al. [80], tail-biting behavior was also reduced in pigs after appropriate amino acid supplementation, which validates the idea that dietary amino acid deficiency causes stereotypic or abnormal behaviors in pigs.

As mentioned above, sows are subjected to feeding restrictions during pregnancy, which may lead to chronic starvation and the presence of long-term frustrated feeding behaviors. Therefore, restricted feeding is one of the most important causes of sham-chewing in sows [81]. However, as the pregnancy progresses, the fetus gradually increases in size and compresses the sow's digestive tract, which may make it easier to reach a state of satiety. As a result, sham-chewing behavior in pregnant sows decreases as the pregnancy progresses [82].

All of the factors, leading to stereotypic behaviors, are associated with feeding activities, which are consistent with Lawrence and Terlouw's [83] suggestion that stereotypic behaviors were strongly related to feeding motivation. Similarly, when feeding is poorly managed, animals may experience stress and develop stereotypic behaviors if feeding management is not improved [84]. In intensive pig farming, sows are frequently confined in crates to maximize space utilization while reducing rearing costs [85], and sows are restricted in behaviors such as turning, exploring, and learning [40], which is most common in pregnant sows. Salak-Johnson et al. [86] found that increasing the rearing area (i.e., lowering the rearing density) reduced the sham-chewing behavior of gestating sows while keeping the number of animals constant. This might be related to the fact that lowering the stocking density resulted in less boredom in sows. Liu et al. [87] and Liu et al. [88] compared the effects of individual stall (IS) and group housing system (GS) on the behaviors of pregnant sows and found that on days 40, 70, and 100 of the test periods, the frequency of sham-chewing behavior of sows in IS was significantly higher than that in GS sows; however, GS increased the exploratory behavior of the pregnant sows. In addition, the stress levels in the GS pregnant sows were lower than that in the IS group (plasma cortisol concentrations in the GS group were lower than in the IS group). In the EU countries, pregnant sows (the period between 4 weeks after insemination and 1 week before farrowing) are legally required to be in group housing, but lactating sows are allowed to be housed in separate farrowing crates, the reason for this is that when lactating sows are kept in GS, the piglets may be crushed by the sow, resulting in excessive mortality of the piglets [40]. Inter-sucking was also found to be unavoidable in group housing in the study by Nicolaisen et al. [40].

To summarize, the sham-chewing behavior of pigs is mainly influenced by diet composition (fiber or protein content), feeding regime (free or restricted), stocking density, feeding mode (group or individual), and the stage of pregnancy of sows.

Poultry

Research on stereotypic behaviors in poultry has focused on chickens, with less research on stereotypic behaviors in ducks and geese. Research over the last few decades has shown that early feeding restriction controls growth and body fat deposition in broiler chickens [37], and this presents the same problems as in cattle and pigs—due to insufficient feeding time, chickens express more foraging behavior and progressively develop stereotypic foraging behavior [89]. Due to the inadequacy of diet, poultry tend to redirect their pecking behavior to objects in the chicken coop [90], and these objects often include drinkers, feeders, fences, etc. [91]. Researchers have found that when switching to twice-daily feedings there was a reduction in stereotypic pecking behavior in broilers [92] and the same results were found in the study of van Emous and Men [93]; on the other hand, changing the diet can also reduce pecking behavior in chickens. In a study by van Emous et al. [91], feeding a low-protein diet resulted in a 70% reduction in stereotypic pecking behavior in broilers due to the fact that feeding a low-protein diet prolonged the feeding time of broilers. This is in contrast to the above results of protein deficiency leading to tail-biting behavior in pigs, which may be because of species differences. When poultry are fed a low protein diet, they increase their protein intake by increasing feed intake and feeding behavior is fully expressed; however, when pigs are fed a low protein diet, they will stop feeding and look for a high protein diet, leading to increased foraging behavior [94]. As foraging increases, tail-biting eventually occurs [95].

In addition, feeding dilute diets (diets with crude fiber) reduced feather pecking and non-food object pecking (pecking at feeders or enclosures [96]) behaviors in female broilers. De Jong et al. [92] and Zuidhof et al. [97] also found that dilution diets reduced stereotypic pecking behavior (including feather pecking and object pecking) in broilers. Dilution diets are made by adding fiber to the original diets. Therefore, the reason why dilution diets reduce pecking behavior is that fiber reduces pecking behavior by increasing satiety through prolonging the food emptying time.

Other farm animals

Compared to ruminants, pigs and poultry, horses have a lower farming number. Horses kept in stables for a long time are prone to oral stereotypic behaviors [98], while horses used for show or hire are less likely to exhibit oral stereotypic behaviors [99]. Common stereotypic behaviors of horses include crib-biting, sham-chewing, and others [100]. In a study by Whisher et al. [101], horses on diets supplemented with oats showed less crib-biting than horses on diets supplemented with sweetened grain; in a similar study by Gillham et al. [102], crib-biting was found to increase when horses were on sweetened grain diets. This was also because foraging oats increased the horse's feeding time and satiety. For the same amount of energy, the volume of oats was larger than that of sweetened grain, which may account for why the oats can increase satiety [101]. Albright et al. [103] found that concentrate feeds increased crib-biting behavior in horses, probably due to their higher palatability. Furthermore, the sweetness of feed promotes the release of endogenous opioids, which induce oral stereotypic behavior. There have been studies on genes and stereotypic behaviors of horses. However, some genes that may contribute to stereotypic behaviors (e.g., dopamine [DA] receptor and serotonin receptor) do not differ in expression [104].

Rabbits are also a type of farm animal, but research on rabbit stereotypic behaviors have mainly focused on pet and laboratory rabbits because they are small in size and more difficult to observe in large groups. Like other animals, rabbits can also exhibit oral stereotypic behaviors such as sham-chewing, bar-biting, and licking parts of the cage [105]. Feeding factors can alter stereotypic behaviors of rabbits and it has been shown that feeding hay is effective in preventing hair chewing in laboratory rabbits [106]. When pet rabbits forage on hay, they take longer to feed and reduce stereotypic behaviors [105]. Under natural conditions, rabbits are herd animals [107], usually consisting of 2-9 females, 2-3 males, and litters. However, under farming conditions it is common for 2-6 rabbits to be housed in cages [108], resulting in restricted expression of social behaviors that can lead to stereotypic behaviors. Increasing the size and enrichment of the cage can increase exploratory behavior and reduce stereotypic behaviors in rabbits [41].

PHYSIOLOGICAL STATE AND STEREOTYPIC BEHAVIORS

Stress state and stereotypic behaviors

Researches on the neurobiology and physiology of stereotypic behaviors in animals were very obscure in the past, but there has been increasing interest in this area in recent years [2], such as the relationship between the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and stereotypic behaviors. The HPA axis is the predominant endocrine regulator of stress in animals, and stimulation of the HPA axis is marked by the secretion of cortisol or corticosterone. When environmental demands lead to a physiological response in animals that lasts for a long time and exceeds the organism's natural ability to regulate, animals will develop chronic stress [109]. Under intensive farming or domestication, animals may experience chronic stress, which may impair the HPA axis [110]. However, the relationship between stereotypic behaviors and cortisol secretion is quite complex, and there are different results in different studies. In a study by Briefer Freymond et al. [111], blood cortisol concentrations were significantly higher in horses which expressed crib-biting than those in normal horses; in a recent study of dairy cows by our research team [22], blood cortisol concentrations were significantly higher in tongue-rolling cows than in normal cows (p = 0.001); and in another study, it was shown that sham-chewing and trough-biting behavior in sows were positively associated with serum cortisol concentrations [4]. However, in an earlier study on equine stereotypic behaviors, there was no difference in blood cortisol concentrations in horses with stereotypic behaviors compared to normal horses [112]; similar results were found in another study on equine stereotypic behaviors [113]. Similarly, in the research by Webb et al. [2], no differences were found between blood cortisol concentrations in calves with stereotypic behaviors and normal calves either. There are multiple explanations for these different results. Cortisol concentrations in animals vary according to circadian rhythms, peaking in the morning and decreasing thereafter [114]. In the same experiment, the sampling might continue for a long period of time because of the large number of subjects which may result in a high cortisol concentration in normal animals that were blooded or saliva-collected earlier and a low cortisol concentration in animals with stereotypic behaviors that were blooded or saliva-collected later. Besides, blood or saliva collection and restraint processes are stressful for animals, and different individuals have different levels of tolerance to the process. Animals with low tolerance levels may develop a stronger stress response, leading to high cortisol concentrations in blood or saliva. In different experiments, the procedures of sample collection and restraint may considerably vary, leading to varying degrees of stress in the animal.

Moreover, stereotypic behavior has been proposed as a stress-coping mechanism according to the “coping hypothesis.” In a study by McBride and Cuddeford [115], it was found that plasma cortisol concentrations decreased after horses exhibited stereotypic behaviors; high frequency tongue-rolling lactating cows had higher milk production than normal cows [22]. However, some research studies do not support the “coping hypothesis”. Fureix et al. [20] found no differences in the plasma cortisol and fecal cortisol concentrations between horses with stereotypic behaviors and normal horses. In their experiment, it was known that the horses were raised in a suboptimal environment, with poor welfare conditions, and their cortisol levels were at a higher level. Therefore, they concluded that it was not possible to show that animals with stereotypic behaviors were better adapted to their environment. Similarly, Pell and McGreevy [112] found that there was no difference in the salivary cortisol concentration between horses with stereotypic behavior and normal horses. In addition, another result showed that the plasma cortisol concentration increased after expressing stereotypic behavior [116]. These indicate that stereotypic behavior may not be a way for animals to cope with stress. Therefore, further research is needed on the relationship between stereotypic behaviors and stress. We should expand the number of experimental samples and study the effects of stereotypic behaviors and stress on organismal metabolism and animal performance through modern biological techniques.

Personality, emotion, and stereotypic behaviors

Stereotypic behaviors are also related to the personality of the animal. Animals with positive personalities can cope with external stimuli by expressing stereotypic behavior, while animals with negative personality tend to respond to stressors through emotional depression [117]. Pigs with a positive disposition likely show significant behavioral changes in response to stress but have low cortisol concentrations [118]. 5-HT and DA are strongly associated with animal behaviors. Animals expressing stereotypic behaviors have higher levels of DA in their bodies [119], while there is a negative correlation between 5-HT and the expression of stereotypic behaviors, and animals that exhibit stereotypic behaviors have low levels of 5-HT [120]. The basal ganglia have a motor regulatory function and DA stimulates basal ganglia activity [121], but 5-HT inhibits basal ganglia activity [122]. Similar to personality, anxiety or psychiatric disorders can also lead to stereotypic behaviors. For example, several studies on human children have shown that children with high anxiety may exhibit more stereotypic behaviors than normal children [123, 124]. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder, and the Shank3B gene is associated with ASD. Researchers using Shank3B knockout to mimic ASD mice found increased anxiety accompanied by increased stereotypic behaviors [10], and after administration of anxiolytic drugs, such as Valium, ASD mice and stress mice showed a significant decrease in anxiety and subsequent decrease in stereotypic behaviors [87, 88].

Boredom, indifference, anxiety, and other negative emotions are often observed in animals that live in impoverished environments [125]. However, there are few studies on the mechanisms of how negative emotions lead to stereotypic behavior. Reducing negative emotions is often related to environmental enrichment. Environmental enrichment affects the activity of the basal ganglia in the brain [126]. Many studies have shown that environmental enrichment increased the dendritic spine density in the basal ganglia of the animals [127, 128] and activated the neurons [128-131]. The striatum and the ventral tegmental area in the basal ganglia are involved in the modulation of various emotions. Turner et al. [131] found that environmental enrichment significantly reduced the stereotypic behavior of deer mice and found higher levels of activation in their ventral tegmental area and multiple striatal regions as well as the motor cortex, frontal cortex, hippocampus, and ventrolateral thalamus. Environmental enrichment also increases the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the striatum of deer mice [132]. BDNF can enhance synaptic plasticity and neuronal activation by increasing the formation of synapses and dendritic spines [126]. Therefore, the relationship between environmental enrichment, emotion, and stereotypic behavior is still mainly focused on the basal ganglia and little is known about other neural or physiological mechanisms.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the causes of oral stereotypic behaviors in farm animals include the expression of foraging behavior, concentrate to forage ratio of diet, the protein content of diet, separation of young animals from their dams, feeding space, and enrichment. The simplest way to reduce stereotypic behaviors in farm animals is to change the composition of their diet but it may only reduce stereotypic behaviors in the short term. Stereotypic behaviors have long been regarded as a sign of poor animal welfare and health status. Even though studies have shown that some animals with stereotypic behaviors may have better production or reproductive performance [21, 22], this does not indicate that they enjoy good welfare status. Next, we need to study the physiological role of stereotypic behaviors such as conducting experiments to verify the “coping hypothesis,” examining whether long-term expression of stereotypic behaviors is beneficial to animals, exploring how to reduce stereotypic behaviors in farm animals, and investigating how to breed breeds of animals that express fewer or even no stereotypic behaviors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Chenyang Li: Conceptualization; writing—original draft. Xianhong Gu: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (32272926) and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP-IAS07).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.