NHC-Supported 2-Sila and 2-Germavinylidenes: Synthesis, Dynamics, First Reactivity and Theoretical Studies

Abstract

2-tetrelavinylidenes (C=EH2; E=Si, Ge) are according to quantum chemical studies the least stable isomers on the [E,C,2H] potential energy hypersurface isomerizing easily via the trans-bent tetrelaacetylenes HE≡CH to the thermodynamically most stable 1-tetrelavinylidenes (E=CH2). Consequently, experimental studies on 2-tetrelavinylidenes (C=ER2) and their derivatives are lacking. Herein we report experimental and theoretical studies of the first N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) supported 2-silavinylidene (NHC)C=SiBr(Tbb) (1-Si: NHC=C[N(Dipp)CH]2, Dipp=2,6-diisopropylphenyl, Tbb=2,6-bis[bis(trimethylsilyl)methyl]-4-tert-butylphenyl) and the isovalent 2-germavinylidenes (NHC)C=GeBr(R) (1-Ge, 1-GeMind: R=Tbb, Mind (1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7-octamethyl-s-hydrindacene-4-yl)). The NHC-supported 2-tetrelavinylidenes were obtained selectively from the 1,2-dibromoditetrelenes (E)-(R)BrE=EBr(R) using the diazoolefin (NHC)CN2 as vinylidene transfer reagent. 1-E (E=Si, Ge) have a planar vinylidene core, a bent-dicoordinated vinylidene carbon atom (CVNL), a very short E=CVNL bond and an almost orthogonal orientation of the NHC five-membered ring to the vinylidene core. Quantum chemical analysis of the electronic structures of 1-E suggest a significantly bent 1-tetrelaallene and tetrelyne character. NMR studies shed light into the dynamics of 1-E involving NHC-rotation around the CVNL−CNHC bond with a low activation barrier. Furthermore, the synthetic potential of 1-E is demonstrated by the synthesis and full characterization of the unprecedented NHC-supported bromogermynes BrGe=C(EBr2Tbb)(NHC) (2-SiGe: E=Si; 2-GeGe: E=Ge).

1 Introduction

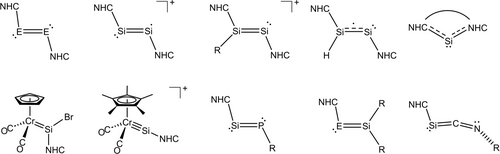

During the last 15 years N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) have been shown to be particularly suitable Lewis-bases for the thermodynamic stabilization of highly reactive main-group element species1-5 leading in the case of silicon and germanium to a series of isolable closed-shell, and open-shell, multiply-bonded compounds with intriguing electronic structures and a great synthetic potential (Figure 1).6-19 A particularly intriguing class among them are the NHC-supported ditetrelavinylidenes (NHC)E=SiR2 (Figure 1), which may be considered as the dismutational isomers of the NHC-supported ditetrelynes RE=SiR(NHC).

Examples of NHC-containing multiple-bonded compounds of silicon and germanium (E=Si, Ge; NHC=N-heterocyclic carbene); formal charges were not included in the Lewis structures for the sake of simplicity.

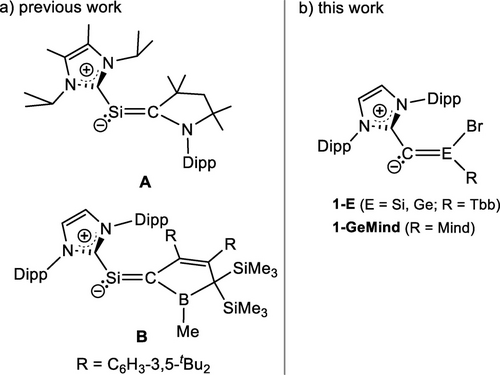

While only few inspiring precedents of stable (NHC)E=SiR2 (E =Si,17, 18 Ge;15, 16 Figure 1) and 1-silavinylidenes ((NHC)Si=CR2; A20 and B,21 Figure 2a) have been reported, isolable NHC-stabilized 2-tetrelavinylidenes ((NHC)C=ER2; E=Si, Ge), the missing link of the NHC-supported heavier vinylidene series, are so far unknown. Quantum chemical studies predicted that (NHC)C=SiR2 (NHC=C[N(tBu)CH]2; R =Me, tBu, Dipp, F, Cl) are thermodynamically more stable than their 1-silavinylidene isomers (NHC)Si=CR2,22 which were speculated to be prone to head-to-head dimerization.23 However, no experimental studies of (NHC)C=ER2 (E =Si, Ge) have been reported so far most probably due to a lack of suitable synthetic equivalents of 2-tetrelavinylidene (C=ER2) synthons. Experimental studies on the parent 2-tetrelavinylidenes (C=EH2; E = Si, Ge) and their derivatives are also lacking due to their thermodynamic instability and kinetic lability. In fact, the parent 2-tetrelavinylidenes (C=EH2) are the highest energy species in the potential energy surface of [E,C,2H] (E=Si, Ge), which are predicted to isomerize to the thermodynamically most stable 1-tetrelavinylidenes (E=CH2) via the respective trans-bent tetrelynes (H−E≡C−H) in two steps with very low activation barriers.24-29 Accordingly, no evidence could be obtained for the formation of C=SiH2 and C=GeH2 during the gas phase generation of 1-silavinylidene (Si=CH2) and 1-germavinylidene (Ge=CH2) from SiH3CH2Cl,30 SiH4/CO gas mixture,31 E(CH3)432 or from the reaction of ground-state carbon atoms with Si2H633 and GeH434 under single-collision conditions. Moreover, NHC-supported 2-silavinylidenes were predicted to be thermodynamically less stable than their head-to-tail dimers in the absence of steric protection,22 illustrating the challenge to access these compounds.

a) NHC-supported 1-silavinylidenes; b) NHC-supported 2-silavinylidene (1-Si) and 2-germavinylidenes (1-Ge, 1-GeMind); Tbb=2,6-bis[bis(trimethylsilyl)methyl]-4-tert-butylphenyl), Mind=1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7-octamethyl-s-hydrindacene-4-yl, Dipp = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl.

Based on these results, we presumed that a sterically demanding NHC group and a stereo-electronically tuned 2-tetrelavinylidene fragment would be required for the isolation of an NHC-supported 2-tetrelavinylidene. Recently, we have reported a Si(NHC) group transfer reaction of the NHC-supported iminosilenylidene (NHC)Si=C=N−ArMes (NHC =C[N(Dipp)CH2]2, Dipp=2,6-diisopropylphenyl, ArMes=2,6-dimesitylphenyl), taking advantage of its displaceable isonitrile ligand.19 We surmised to use a similar synthetic method to enter into the 2-tetrelavinylidene chemistry using a N-heterocyclic diazoolefin (NHC)CN2 as a potent C(NHC) vinylidene group transfer reagent.35, 36 The successful implementation of this conjecture is presented in this work with the isolation, characterization and reactivity of the first NHC-supported 2-tetrelavinylidenes 1-Si, 1-Ge and 1-GeMind (Figure 2b).

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Synthesis and Characterization of NHC-Supported 2-Tetrelavinylidenes 1-Si, 1-Ge and 1-GeMind

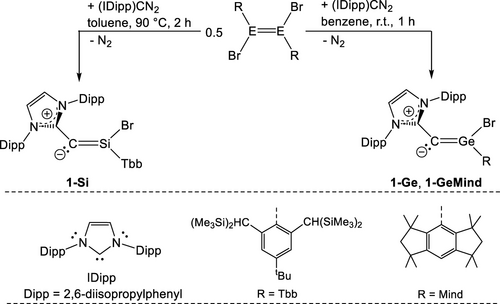

Entry to this chemistry was provided by the 1,2-dibromoditetrelenes (E)-(R)BrE=EBr(R) (E=Si, Ge; R=Tbb (C6H2−2,6-(CH(SiMe3)2)2−4-tBu), Mind (1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7-octamethyl-s-hydrindacen-4-yl)) and the diazoolefin (IDipp)CN2 (IDipp = C[N(Dipp)CH]2).36 Heating of a 2 : 1 molar mixture of (IDipp)CN2 and 1,2-dibromodisilene (E)-(Tbb)BrSi=SiBr(Tbb) in toluene at 90 °C was accompanied by a gradual color change of the reaction solution from orange-yellow to intense orange (Scheme 1). Reaction monitoring by 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed the formation of the desired NHC-supported 2-silavinylidene 1-Si as a major product. 1-Si was isolated after work-up as an extremely air-sensitive, bright yellow solid in 59 % yield. Reaction of (IDipp)CN2 with the 1,2-dibromodigermenes (E)-(R)BrGe=GeBr(R) (R=Tbb, Mind) proceeded rapidly in benzene at room temperature to afford selectively the isovalent 2-germavinylidenes 1-Ge and 1-GeMind, which were isolated after crystallization in high yields as air-sensitive, orange-brown and mustard-yellow solids, respectively (Scheme 1).

Synthesis of the NHC-supported 2-tetrelavinylidenes 1-Si, 1-Ge and 1-GeMind.

Compounds 1-Si, 1-Ge and 1-GeMind display high thermal stability, decomposing unselectively upon melting at 220 °C (1-Si), 162 °C (1-Ge) and 151 °C (1-Ge-Mind). Upon strict exclusion of air their solutions in (D6)benzene are stable at 80 °C for several hours, the 1H NMR spectra displaying no sign of decomposition.

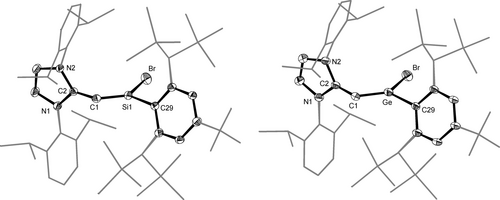

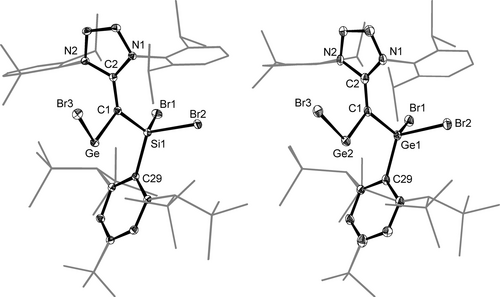

1-Si, 1-Ge and 1-GeMind are the first single donor-stabilized 2-sila- and 2-germavinylidenes to be reported and were characterized by single crystal X-ray diffraction (sc-XRD) analyses, multinuclear NMR spectroscopy and UV/Vis spectroscopy. The molecular structures display the following features (Figure 3, Table 1 and ESI, chapter 5):

DIAMOND plots of the molecular structures of NHC-supported 2-silavinylidene 1-Si (left) and 2-germavinylidene 1-Ge (right); thermal ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability and hydrogen atoms are omitted; the peripheral substituents of the NHC and Tbb groups are presented in wire frame for the sake of clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°): (1-Si): Si1−C1 1.657(2), Si1−C29 1.863(2), Si1−Br 2.2655(7), C1−C2 1.358(3), C2−N1 1.391(3), C2−N2 1.391(3); Si1−C1−C2 142.9(2), C1−Si1−Br 120.64(9), C1−Si1−C29 130.8(1), Br−Si1−C29 108.30(8); βSi=C/NHC=89.9(1)°, θSi=C/NHC=89.7(2)°. (1-Ge): Ge−C1 1.746(6), Ge−C29 1.935(6), Ge−Br 2.394(1), C1−C2 1.376(9), C2−N1 1.380(8), C2−N2 1.394(8); Ge−C1−C2 131.3(5), C1−Ge−Br 120.0(2), C1−Ge−C29 130.6(3), Br−Ge−C29 107.7(2); βGe=C/NHC=86.2(2)°, θGe=C/NHC=89.7(2)°.

Compound |

E−CVNL/ E−Ccent (Å) |

CVNL−CNHC/ Ccent−Cter (Å)[a] |

∡(E−CVNL−CNHC)/ ∡(E−Ccent−Cter) [a] (°) |

Σ∡(E) (°) |

θE=C/NHC/ θ[a] (°) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(IDipp)C=SiBr(Tbb) (1-Si) |

1.657(2) |

1.358(3) |

142.9(2) |

359.7 |

89.7(2) |

This work |

(IDipp)C=GeBr(Tbb) (1-Ge) |

1.746(6) |

1.376(9) |

131.3(5) |

358.3 |

89.7(2) |

This work |

(IDipp)C=GeBr(Mind) (1-GeMind) |

1.724(2) |

1.377(3) |

135.0(2) |

359.4 |

85.5(1) |

This work |

(fluorenyl)C=C=Si(Mes*)(1-Ad)[b] |

1.704(4) |

1.324(5) |

173.5(3) |

360 |

88.3 |

[38] |

(tBu)(Ph)C=C=Si(Tipp)2[b] |

1.693(3) |

1.325(4) |

172.0(3) |

357.2 |

82.9 |

[39] |

(SiMe3)(tBu)C=C=Si(ArMes)(tBu)[b] |

1.694(2) |

1.324(3) |

174.2(2) |

360 |

79.8 |

[40] |

(tBu)(Ph)C=C=Ge(Tipp)2 |

1.783(2) |

1.314(2) |

159.2(2) |

348.4 |

83.5 |

[44] |

- [a] Ccent and Cter is the central and terminal carbon atom of the 1-tetrelaallene, respectively; θ is the interplanar angle between the silylene/germylene and carbene coordination planes; [b] Mes*=2,4,6-tri-tert-butylphenyl), 1-Ad=1-adamantyl, Tipp=2,4,6-tris-isopropylphenyl, ArMes=2,6-dimesitylphenyl.

a) the Si1−C1 and Ge−C1 bond lengths are remarkably short (d(E−CVNL): 1.657(2) Å (1-Si), 1.746(6) Å (1-Ge), 1.724(2) Å (1-GeMind); Table 1). In fact, the Si−CVNL distance of 1-Si is considerably shorter than the shortest Si=C double bond length reported so far for a silene (1.702(5) Å, Me2Si=C(SiMe3)(SitBu2Me)).37 It is even shorter than the Si=C double bond lengths of 1-silaallenes (1.693(3)–1.704(4) Å, Table 1),38-40 the NHC-supported 1-silavinylidenes A (1.792(4) Å)20 and B (1.784(2) Å)21 and the NHC-supported iminosilenylidene (NHC)Si=C=N(ArMes) (1.784(1) Å).19 Notably, the Si−CVNL bond length is similar to that of the phosphane-supported silynes (2-(P(NtBu)2SiMe2)-3-((Dipp)N)-norbornene)SiCP(NiPr2)2 (1.667(3) Å)41 and [(2-(P(NtBu)2SiMe2)-3-((Dipp)N)-norbornene)SiCPPh2(NiPr2)][B(ArF)4] (1.631(2) Å, ArF=C6H3−3,5-(CF3)2).42 Remarkably, the Ge−CVNL bond of 1-GeMind is the shortest crystallographically determined Ge−C bond reported so far. It is much shorter than the Ge=C double bond lengths of the phosphagermaallene (Tipp)(tBu)Ge=C=P(Mes*) (1.761(2) Å),43 the 1-germaallene (Tipp)2Ge=C=C(tBu)(Ph) (1.783(2) Å),44 and the phosphane-supported germyne (2-(P(NtBu)2SiMe2)-3-((Dipp)N)-norbornene)GeCP(NiPr2)2 (1.887(5) Å).45

b) the CVNL−CNHC bond lengths (d(C1−C2): 1.358(3) Å (1-Si), 1.376(9) Å (1-Ge), 1.377(3) (1-GeMind)) are significantly longer than the Ccent=Cter double bond lengths of 1-tetrelaallenes 1.314(2) −1.325(4) Å, Table 1).38-40, 44 Moreover, the CVNL−CNHC bond lengths lie outside the longer end of the range of the Ccent−CNHC bond lengths reported for carbodicarbenes containing at least one NHC moiety (1.318 −1.346 Å).46-48

c) the dicoordinated vinylidene center CVNL displays a bent geometry (∡(Si1−CVNL−CNHC)=142.9(2)° (1-Si), ∡(Ge−CVNL−CNHC)=131.3(5)° (1-Ge), 135.0(2)° (1-GeMind)). The angle at CVNL is smaller than those of 1-silaallenes (∡(Si−Ccent−Cter)=172.0° −174.2°, Table 1)38-40 and the 1-germaallene (tBu)(Ph)C=C=GeTipp2 (∡(Ge−Ccent−Cter)=159.2°),44 but considerably larger compared to the ∠(CNHC−Si−Si) angle of the NHC-supported disilavinylidene (Z)-(SIDipp)Si=SiBr(Tbb) (97.6(1)°, SIDipp=C[N(Dipp)CH2]2).17 Of note, the angles at CVNL lie in the range of the ∠(CNHC−Ccent−CNHC) angles reported for carbodicarbenes containing at least one NHC moiety (134.8° −146.2°).46-48

d) the silicon center is trigonal planar coordinated (Σ∡(Si1)=359.7°) and the 2-silavinylidene mean-plane defined by the atoms Si1, CVNL, Br and CTbb (C29) is orthogonal to the NHC mean-plane passing through the atoms of the N-heterocyclic ring as evidenced by the silavinylidene-NHC interplanar angle βSi=C/NHC of 89.9(1)° or the twist angle θSi=C/NHC of 89.7(2)° between the NHC mean-plane and the silylene plane defined by the atoms Si1, Br and CTbb. This arrangement leads to a nearly Cs-symmetric structure with the plane of symmetry passing through the 2-silavinylidene core and bisecting the NHC five-membered ring. The IDipp and Tbb groups of 1-Si adopt an anti-periplanar conformation with a torsion angle ∠(C2−C1−Si1−C29) of 172.9(3)°. These conformational features are also found in the disilicon congener (Z)-(SIDipp)Si=SiBr(Tbb): β=93.5(1)°, θ=87.1(1)°, torsion angle (∡(CNHC−Si−Si−CTbb)=177.3(2)°).17 The corresponding structural parameters of 1-Ge and 1-GeMind are very similar to those of 1-Si (Table 1). Of note, the Σ∡(Ge) in 1-Ge and 1-GeMind is different from that of the 1-germaallene (tBu)(Ph)C=C=Ge(Tipp)2, which contains a slightly trigonal pyramidal bonded Ge atom (Σ∡(Ge)=348.4°).44

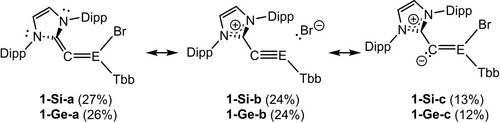

Based on the comparative assessment of the structural parameters, the E−CVNL (E=Si, Ge) bond of 1-E (E=Si, Ge) and 1-GeMind can be described as E=CVNL double bonds with a considerable E≡CVNL triple bond character, and the CVNL−CNHC bonds have a partial double bond character in line with the results of the Natural Resonance Theory (NRT) in NBO basis, according to which the resonance hybrid of the gas phase optimized structures (1-Si)calc and (1-Ge)calc is mainly composed of three Natural Lewis Structures (NLSs), a bent 1-tetrelaallene type (1-E-a), a cationic tetrelyne type (1-E-b) and an ylide type structure (1-E-c) (Figure 4).

Natural Lewis Structures (NLSs) of (1-Si)calc and (1-Ge)calc obtained from local NRT analysis.

The NHC-supported 2-tetrelavinylidenes 1-Si and 1-Ge were characterized in solution by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy. In the 29Si NMR spectrum 1-Si displays a characteristic singlet signal for the unsaturated Si atom at δSi=−37.0 ppm. This appears at much higher field than those of 1-silaallenes (13.1–61.7 ppm, Table 2),38-40, 49 the NHC-supported disilavinylidene (Z)-(SIDipp)Si=SiBr(Tbb) (δSiBr(Tbb)=86.0 ppm),17 the bromosilene Br(Rs)Si=CH(C6H3-3,5-tBu2) (85.2 ppm, Rs=C(SiMe3)2(CH2tBu)),50 or the 1,2-dibromodisilene (E)-(Tbb)BrSi=SiBr(Tbb) (84.1 ppm),51 and is also noticeably high-field shifted in comparison to those of naturally polarized silenes (δSi=17.5–144.2 ppm).52 This suggests that the Si=C double bond of 1-Si is electronically different from the Si=C double bond of naturally polarized silenes and may be attributed to the cationic silyne character of 1-Si (Figure 4). In fact, the 29Si chemical shift of 1-Si compares very well with that of the phosphane-supported cationic silyne [(2-(P(NtBu)2SiMe2)-3-((Dipp)N)-norbornene)SiCPPh2(NiPr2)][B(ArF)4] (δSi=−32.5 ppm, ArF=C6H3−3,5-(CF3)2).42 Notably, the 1J(Si,CVNL) coupling constant of 1-Si of 147 Hz is considerably larger than those of silenes (1J(Si,Csp2)≈84 Hz) and even slightly larger than the largest 1J(Si,Ccent) reported so far for 1-silaallenes (142.4 Hz).39, 40

Compound |

δSi (ppm) |

δCVNL/δCcent (ppm) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

(IDipp)C=SiBr(Tbb) (1-Si) |

−37.0 |

142.1 |

This work |

(IDipp)C=GeBr(Tbb) (1-Ge) |

– |

167.7 |

This work |

(IDipp)C=GeBr(Mind) (1-GeMind) |

– |

161.5 |

This work |

(fluorenyl)C=C=Si((Mes*)(1-Ad)[a] |

48.4 |

225.7 |

[38] |

(tBu)(Ph)C=C=Si(Tipp)2 |

13.1 |

223.6 |

[39] |

(SiMe3)(tBu)C=C=Si(ArMes)(tBu) |

42.7 |

230.6 |

[40] |

(SiMe3)(tBu)C=C=Si(ArMes)Cl |

49.8 |

– |

[40] |

(R1)(R2)C=C=Si(OSiMe3)(R2)[a] |

61.7 |

282.3 |

[49] |

(tBu)(Ph)C=C=Ge(Tipp)2 |

– |

235.1 |

[44] |

C(NHC1)2[a] |

– |

110.2 |

[46] |

C(NHC1)(NHC2)[a] |

– |

140.5 |

[48] |

- [a] 1-Ad=1-adamantyl, R1=SitBuMe2, R2=SiMetBu2, NHC1=1,3-dimethylbenzimidazol-2-ylidene; NHC2=1,3,3-trimethylindolin-2-ylidene.

In the 13C NMR spectrum the signal of the vinylidene carbon atom CVNL appears at a much higher field (δCVNL/ppm=142.1 (1-Si), 167.7 (1-Ge), 161.5 (1-GeMind)) compared to that of the central carbon atom of 1-tetrelaallenes (δCcent=223.6–282.3 ppm, Table 2), but lies closer to that of the central carbon atom of carbodicarbenes containing at least one NHC group (δCcent=110.2, 140.5 ppm, Table 2). Thus, the CVNL chemical shifts of 1-E and 1-GeMind indicate an ylidic character of the CVNL−CNHC bond (CVNL(δ−)−CNHC(δ+)).

2.2 Studies of the Stereodynamics of 1-Si and 1-Ge by Dynamic NMR Spectroscopy

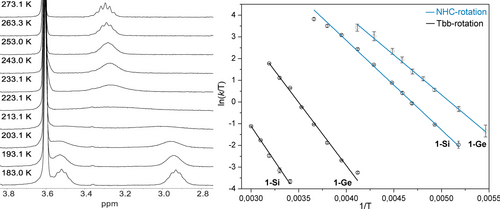

Compounds 1-Si and 1-Ge show dynamics in solution on the NMR time scale. Given the nearly Cs-symmetric molecular structure of 1-E (Figure 3) the C2/C6 bonded isopropyl groups of the enantiotopic Dipp substituents are diastereotopic and hence should give rise to two septet signals for the four methine protons in the intensity ratio of 2 : 2. Similarly, two 1H NMR singlet signals in the intensity ratio of 18 : 18 would be expected for the diastereotopic SiMe3 groups of the enantiotopic C2,6-bonded disyl groups of the Tbb substituent. However, the 1H NMR spectra of 1-E recorded at 273 K in (D8)THF display only one methine septet signal (Figure 5 (left)) and in the case of 1-Ge one broad SiMe3 signal (ESI, chapter 3.3).

(left) Stack plot of the excerpts (2.8 −3.8 ppm) of the variable temperature (VT) 1H NMR spectra (300.1 MHz, (D8)THF) of 1-Si showing an equally populated two site chemical exchange of the methine septet signals (C2,6−CHMeAMeB) of the Dipp substituents of the NHC group; (right) Eyring plots of the NHC rotation and Tbb rotation in 1-Si and 1-Ge.

Two dynamic processes were resolved by variable temperature (VT) 1H NMR experiments in the temperature range of 183–333 K (ESI, chapter 3). The first process involves a NHC rotation about the CVNL−CNHC bond, as evidenced, for example, by the broadening-coalescencing-sharpening of the two methine septet signals (C2,6−CHMeAMeB) of the Dipp groups in 1-Si and 1-Ge upon increasing the temperature from the slow exchange limit (Figure 5 (left); ESI, chapter 3.2.1). The second process involves a Tbb rotation about the E−CTbb bond (E=Si, Ge) leading to a site exchange of the SiMe3 groups (ESI, chapter 3.2.2). Standard activation parameters of the NHC and the Tbb rotation were determined by Eyring analysis of the temperature dependent exchange rate constants (k/Hz), which were obtained by gNMR full lineshape analysis of the variable temperature (VT) 1H NMR spectra (Figure 5 (right), Table 3). In addition, an analysis of the effect of the systematic errors in natural linewidth (Δν°1/2) on the activation parameters was carried out, which was shown to give a minimal enthalpy-entropy compensation in Eyring analysis for the NHC rotation allowing reliable estimates of the standard activation enthalpy (Δ≠H°) and standard activation entropy (Δ≠S°) (ESI, chapter 3.3).53

compound |

solvent |

Δ≠H° [a] |

Δ≠S° [a] |

Δ≠G° [a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

NHC-rotation |

||||

(IDipp)C=SiBr(Tbb) (1-Si) |

(D8)THF |

34.4(1.9) |

−36.2(8.4) |

45.2(3.0) |

(IDipp)C=GeBr(Tbb) (1-Ge) |

(D8)THF |

30.5(1.9) |

−42.3(9.1) |

43.1(3.1) |

BrGe=C(SiBr2Tbb)(IDipp) (2-SiGe) |

(D8)Toluene |

50.3(2.2) |

−18.5(6.8) |

55.8(2.9) |

BrGe=C(GeBr2Tbb)(IDipp) (2-GeGe) |

(D8)Toluene |

48.9(2.3) |

−8.8(7.2) |

51.5(3.0) |

Tbb-rotation |

||||

(IDipp)C=SiBr(Tbb) (1-Si) |

(D8)THF |

54.4(6.2) |

−43.7(19.6) |

67.5(8.2) |

(IDipp)C=SiBr(Tbb) (1-Ge) |

(D8)THF |

48.5(4.9) |

−27.7(17.3) |

56.8(6.8) |

BrGe=C(SiBr2Tbb)(IDipp) (2-SiGe) |

(D8)Toluene |

62.0(6.9) |

−0.8(22.8) |

62.2(9.3) |

BrGe=C(GeBr2Tbb)(IDipp) (2-GeGe) |

(D8)Toluene |

52.4(6.0) |

0.8(23.5) |

52.1(8.8) |

- [a] Δ≠H° and Δ≠G° values are in kJ ⋅ mol−1; Δ≠S° values are in J ⋅ (K ⋅ mol)−1; the total errors (σtotal=σsys+σstat) in parentheses are quoted in two standard deviations from the means; a bound for the natural linewidth error σsys(Δν°1/2) of ±0.3 Hz was considered in the analysis of the systematic error.

The standard activation enthalpy (Δ≠H°) for the NHC rotation in 1-Si (34.4(1.9) kJ ⋅ mol−1) and 1-Ge (30.5(1.9) kJ ⋅ mol−1) is lower than that for the Tbb rotation (1-Si: Δ≠H°=54.4(6.2) kJ ⋅ mol−1; 1-Ge: Δ≠H°=48.5(4.9) kJ ⋅ mol−1). It is also lower than the standard activation enthalpy for the C=C bond rotation in a series of 1,1-diamino alkenes containing one or two acceptor groups (Δ≠H°=71.0–98.8 kJ ⋅ mol−1; ESI, chapter 3.4),54 the latter being in general much lower than those of normal olefins (~270 kJ ⋅ mol−1). Moreover, the standard free activation energy (Δ≠G°) for the NHC rotation in 1-Si (45.2(3.0) kJ ⋅ mol−1) and 1-Ge (43.1(3.1) kJ ⋅ mol−1) is comparable to the free activation energy of C=C double bond rotation in a 1,1-diborylallene ((Δ≠G(183 K)=36.1 kJ ⋅ mol−1),55 for which a strongly polarized C=C bond has been suggested to account for the facile planarization of the allene core.

Overall, these comparisons suggest a considerable push-pull character of the CVNL−CNHC partial double bond of 1-Si and 1-Ge in agreement with the results of −i) the NBO analysis showing 0.5 non-Lewis electrons in the π*(CVNL−CNHC) NBO (see below; ESI, chapters 6.5 and 6.6), ii) the NRT analysis revealing that natural Lewis structures with a CVNL−CNHC single bond contribute in total ~40 % to the resonance hybrid (Figure 4) and iii) the potential energy surface scans (PES) of the torsion angle ∠(Si−CVNL−CNHC−N1) of (1-Si)calc showing that the coplanar rotamer (1-Si−C)calc (∠(Si−CVNL−CNHC)=143.0°, θSi=C/NHC=7.0°) lies +45.0 kJ ⋅ mol−1 higher in energy relative to (1-Si)calc (∠(Si−CVNL−CNHC)=143.8°, θSi=C/NHC=87.6°; ESI, chapter 6.8).

Notably, the standard activation entropy for the NHC rotation in 1-Si and 1-Ge is considerably negative (Δ≠S°/J ⋅ (mol ⋅ K)−1=−36.2(8.4) (1-Si), −42.3(9.1) (1-Ge)). Large negative activation entropies were obtained by dynamic NMR spectroscopy for the C=C bond rotations of push-pull olefins with a planar ground-state structure in polar solvents, and were attributed to the charge separated transition-state featuring orthogonal arrangements of the two CR2 fragments (Δ≠S°/ J ⋅ (mol ⋅ K)−1=(−27.2)–(−51.7)). In comparison, large positive activation entropies were found for the C=C bond rotation of twisted olefins with a considerable charge separation in the ground-state, for which rotation proceeds via a planar transition-state.54 Taking this into consideration, the activation entropy of 1-Si and 1-Ge suggests a higher degree of charge separation in the transition-state than the ground-state during NHC rotation.

2.3 First Reactivity Study of 1-Si and 1-Ge: Synthesis and Characterization of NHC-Supported Bromogermynes 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe

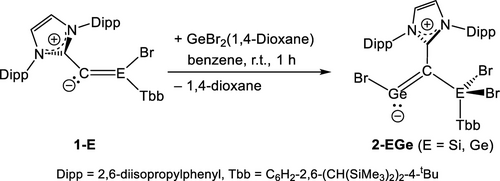

Preliminary reactivity studies were carried out to probe the nature of the E=CVNL bonds of 1-Si and 1-Ge. Both compounds undergo with GeBr2(1,4-dioxane) at room temperature in benzene a 1,2-addition to the E=CVNL bond to afford selectively the NHC-supported bromogermynes 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe, which after work-up were isolated as highly air-sensitive, yellow solids in high yields (Scheme 2, ESI, chapters 2.5 and 2.6). Compounds 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe are thermally stable solids, decomposing upon melting at 217 °C (2-SiGe) and 173 °C (2-GeGe).

Synthesis of the NHC-supported bromogermynes 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe.

The molecular structures of 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe were determined by sc-XRD analyses and feature a bent-dicoordinated Ge-center (∡(CVNL−Ge−Br3)=101.97(4)° (2-SiGe), ∡(CVNL-Ge2−Br3)=105.1(2)° (2-GeGe)) suggesting the presence of a stereochemically active lone pair at the Ge center (Figure 6). The bromogermyne cores of 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe display a distorted trans-bent geometry as evidenced by the torsion angle Br3−Ge/Ge2−CVNL−E of 162.6(1)° and 149.7(1)°, respectively. The CVNL center is trigonal planar coordinated (Σ∡(CVNL)=359.0° (2-SiGe), 358.2° (2-GeGe)) and the NHC five-membered ring is considerably tilted out of the plane defined by the CNHC, CVNL and Ge atoms, as evidenced by the interplanar angle ϕNHC of 67.9(1)° (2-SiGe) and 88.8(3)° (2-GeGe). This conformation is different from that of the vinyl tetrylenes E{C(H)=NHC}2 (E=Si, Ge; NHC=C[N(Dipp)CMe]2),56, 57 which display a coplanar arrangement of the NHC five-membered ring (ϕNHC≈0°), but similar to that found for the NHC-supported ditetrelynes RE=ER(NHC) (ϕNHC=42.48(9)°–82.14(7)°; ESI, Table S24). Accordingly, the CVNL−CNHC bonds of 2-SiGe (1.444(2) Å) and 2-GeGe (1.447(7) Å) are significantly longer than those of the vinyl tetrylenes E{C(H)=NHC}2 (1.375(2) Å (E=Si), 1.361(4) (E=Ge))56, 57 and also longer than those of 1-Si (1.358(3) Å) or 1-Ge (1.376(9) Å), and approach the values of Csp2−Csp2 single bonds (1.460 Å).58 The Ge/Ge2−CVNL bond lengths of 2-SiGe (1.923(1) Å) and 2-GeGe (1.921(5) Å) are 0.17 Å longer than the calculated Ge≡C triple bond length (1.754 Å) of the germyne (Tbt)Ge≡C(Tbt) (Tbt = C6H2−2,4,6-(CH(SiMe3)2)3).59 However, they are near the upper-end of the range of Ge=Csp2 double bond lengths reported in the Cambridge Structural Database for germaethenes (1.770–1.894 Å), and are shorter than a typical Ge−Csp2 single bond (2.01 Å). These comparisons suggest some π-bond character in the Ge/Ge2−CVNL bonds of 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe, which is nicely reflected in the HOMO-1 of these compounds (ESI, chapter 6.11). A comparison of the dE=E' bond lengths of the NHC-supported ditetrelynes RE=E'R(NHC) (E=Si, Ge; E’ = C, Si, Ge) with those of the ditetrelynes RE≡E'R shows that the magnitude of bond elongation Δd follows the trend ΔdGeC (0.17 Å)>ΔdSiSi (0.14 Å)>ΔdGeGe (0.06 Å) (ESI, Table S24) probably due to the increased E’−CNHC interaction in the direction E'=C>Si>Ge.

DIAMOND plots of the molecular structures of the NHC-supported bromogermynes 2-SiGe (left) and 2-GeGe (right); thermal ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability level and the hydrogen atoms are omitted; the peripheral substituents of the NHC and Tbb groups are presented in wire frame for the sake of clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°): (2-SiGe): Ge−C1 1.923(1), Ge−Br3 2.4777(2), Si1−C1 1.807(1), Si1−C29 1.918(1), Si1−Br1 2.2575(4), Si1−Br2 2.2666(4), C1−C2 1.444(2), C2−N1 1.382(2), C2−N2 1.378(2), C1−Ge−Br3 101.97(4), Ge−C1−Si1 103.93(6), Ge−C1−C2 120.82(9), Si1−C1−C2 134.21(9); ϕNHC=67.9(1)°. (2-GeGe): Ge2−C1 1.921(5), Ge2−Br3 2.4586(8), Ge1−C1 1.902(5), Ge1−C29 1.994(5), Ge1−Br1 2.3422(7), Ge1−Br2 2.3674(7), C1−C2 1.447(7), C2−N1 1.368(6), C2−N2 1.387(6), C1−Ge2−Br3 105.1(2), Ge2−C1−Ge1 102.4(2), Ge2−C1−C2 123.9(3), Ge1−C1−C2 131.9(3).

Compounds 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe were also characterized by multi-nuclear NMR spectroscopy. The 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra in solution confirmed the solid-state structures of 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe and unraveled moreover as in case of 1-Si and 1-Ge hindered NHC and Tbb rotations about the respective CVNL−CNHC and E−CTbb bonds, which were studied by VT 1H NMR experiments (ESI, chapter 3). Notably, the activation barriers Δ≠G° for the NHC rotations in 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe are higher than in 1-Si and 1-Ge (Table 3), despite the longer CVNL−CNHC bonds in 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe compared to 1-Si and 1-Ge. This can probably be attributed to increased steric repulsion between the peripheral Dipp groups and the EBr2Tbb group (E=Si, Ge) during NHC rotation in 2-SiGe and 2-GeGe leading to destabilization of the transition state. In the 13C{1H} NMR spectra the chemical shift difference of the CVNL and CNHC atoms (2-SiGe: CVNL=133.6 ppm, CNHC=160.8 ppm; 2-GeGe: CVNL=139.6 ppm, CNHC=161.0 ppm) is indicative of a CVNL(δ−)−CNHC(δ+) bond polarization.

2.4 Quantum Chemical Calculations of (1-Si)calc and (1-Ge)calc

The electronic structure of 1-E (E=Si, Ge) was investigated by density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B97-D3(BJ)−ATM/def2-TZVP level of theory (method-I). Gas phase structure optimizations afforded a minimum structure (1-E)calc with bonding parameters in very good agreement with the experiment (ESI, chapter 6). In particular, the 2-tetrelavinylidene core of (1-E)calc features a bent E−CVNL−CNHC skeleton and a trigonal-planar coordinated tetrel center E ((1-Si)calc: ∠(Si−CVNL−CNHC)=143.8°, Σ∡(Si)=359.8°; (1-Ge)calc: ∠(Ge−CVNL−CNHC)=132.5°, Σ∡(Ge)=358.5°) as found by the sc-XRD studies. Remarkably, unlike 1-Si a linear Si−C−C core was previously predicted for the NHC-supported 2-silavinylidenes (NHC)C=SiR2 (NHC=C[N(tBu)CH]2; R=Me, tBu, Dipp, F, Cl)33 on the B3LYP/def2-TZVPP level of theory and for the 1-silaallenes CH2=C=SiR2 (R=H, Me, SiH3) on various levels of theory.60 Scans of the potential energy hypersurface (PES) of (1-Si)calc showed a continuous increase of the energy upon varying the Si−CVNL−CNHC angle from 140–180° leading to a linear isomer that is only 16 kJ ⋅ mol−1 higher in energy than (1-Si)calc (ESI, chapter 6.2). Notably, inspection of the single-point structures at each scan step revealed that linearization of the E−CVNL−CNHC skeleton is not accompanied by an NHC-rotation or a pyramidalization of the tetrel center. These results indicate, that the skeleton linearization of (1-Si)calc is a low energy process, which however, cannot explain the stereodynamics in solution observed by VT NMR spectroscopy originating from NHC-rotation. In fact, PES scans of the rotation process provided a maximum barrier to the NHC-rotation (ESI, chapter 6.8), which compares well with the experimental barrier (Table 3). The CVNL−CNHC bond cleavage energy (BCE) of (1-E)calc, that is required to give the singlet fragments 1NHC and 1C=EBr(Tbb) in the frozen geometry they adopt in (1-E)calc, amounts 609 kJ ⋅ mol−1 (E=Si) and 571 kJ ⋅ mol−1 (E=Ge), respectively. The large BCE values suggest that 1-E can rather be described as imidazolium-2-tetrelavinylides. The 2-tetrelavinylidenes C=EBr(Tbb) have a triplet ground state with a small triplet-singlet gap ΔES→T (Etriplet–Esinglet) of −32 kJ ⋅ mol−1 (E=Si) and −11 kJ ⋅ mol−1 (E=Ge), respectively. Notably, a comparison of the BCE(CVNL−CNHC) with the sum of the triplet-singlet gaps (∑ΔES→T) of the fragments NHC (ΔES→T=330 kJ ⋅ mol−1) and C=EBr(Tbb) shows that BCE≈∑ΔES→T. This hints to a flat potential energy surface for the E−CVNL−CNHC bending in 1-E as predicted by the CGMT-model.61, 62

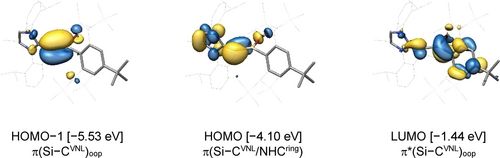

Analysis of the canonical molecular orbitals (MOs) of (1-Si)calc shows that the HOMO-1 is the π(Si−CVNL)oop (oop: out of plane of the 2-silavinylidene core) with the LUMO being the π*(Si−CVNL)oop counterpart that is concentrated at Si. The HOMO is a multi-center π-orbital (Si−CVNL/NHCring) with a large contribution of CVNL, that is bonding between CVNL and Si and non-bonding between CVNL and CNHC (Figure 7 and ESI, chapter 6.4).

Selected canonical molecular orbitals of (1-Si)calc at the B97-D3(BJ)−ATM/def2-TZVP level of theory; the isosurface value is set to 0.04 e1/2 ⋅ Bohr−3/2.

NBO analysis of the wave function of (1-Si)calc gave a leading natural Lewis structure with localized bond pair NBOs for the σ(Si−CVNL), π(Si−CVNL), σ(CVNL−CNHC), π(CVNL−CNHC), σ(Si−CTbb) and σ(Si−Br) bonds with a high Lewis electron occupancy of ≥ 1.9e (Table 4). Both the π(Si−CVNL) and π(CVNL−CNHC) NBOs as well as the σ(Si−CVNL) NBO are strongly polarized toward the CVNL carbon atom (65–72 %) rationalizing the high charge accumulation at the CVNL atom (Table 4). NBO analysis of (1-Ge)calc gave very similar results (ESI, chapter 6.6).

NBO/ A−B |

Occ.[a] |

NHO (A,B)[b], hyb (pol. in %) |

WBI[c] A–B |

NRT-BO[d] tot/cov/ion |

atom/ group |

q/∑q[e] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

σ(Si−CVNL) |

1.97 |

sp1.5(28), sp0.9(72) |

1.6 |

2.0/1.2/0.8 |

Si |

+1.38 |

π(Si−CVNL) |

1.87 |

p(34), p(66) |

CVNL |

−1.00 |

||

σ(CVNL−CNHC) |

1.98 |

sp1.4(46), sp1.3(54) |

1.5 |

1.5/1.2/0.3 |

Br |

−0.37 |

π(CVNL−CNHC) |

1.87 |

sp17.6(65), p(35) |

NHC |

+0.36 |

||

σ(Si−Br) |

1.97 |

sp3.2(26), sp4.6(74) |

0.8 |

0.7/0.4/0.4 |

Tbb |

−0.37 |

σ(Si−CTbb) |

1.94 |

sp1.7(30), sp2.7(70) |

0.8 |

0.9/0.5/0.4 |

SiBr(Tbb) |

+0.64 |

LP(N1/N2) |

1.61/1.61 |

p/p |

|

|

C=SiBr(Tbb) |

−0.36 |

π*(CVNL−CNHC) |

0.48[f] |

|

|

|

|

|

σ*(Si−Br) |

0.20[f] |

|

|

|

|

|

- [a] Occ.=occupancy; [b] NHO=Natural Hybrid Orbital, hyb (hybridization), pol. (polarization)=(Ci)2 ⋅ 100 %, where Ci is the coefficient of the NHO; [c] Wiberg bond index; [d] total, covalent and ionic NRT bond order; [e] q=NPA charge of the atom, ∑q=total NPA charge of the group; [f] non-Lewis electrons.

Considerable delocalization is evidenced in (1-Si)calc by the low Lewis occupancy of the lone pair NBOs LP(N1) and LP(N2) (1.61e each), the presence of non-Lewis electrons in the anti-bonding NBOs π*(CVNL−CNHC) (0.48e) and σ*(Si−Br) (0.20e) (Table 4), and a second order perturbation energy ∑(E(2)) of 346 kJ ⋅ mol−1 for the two LP(N1/N2)→π*(CVNL−CNHC) π-type donor-acceptor interactions as well as an E(2) energy of 46 kJ ⋅ mol−1 for the π(CVNL−CNHC)→σ*(Si−Br) negative hyperconjugation, in line with the results of the NRT analysis (Figure 4; ESI, chapter 6.5).

Natural population analysis (NPA) reveals a considerable charge flow from the NHC to the 2-tetrelavinylidene fragment C=EBr(Tbb) of (1-E)calc resulting in a charge accumulation in the C=EBr(Tbb) fragment (∑q(C=EBr(Tbb))=−0.36 (E=Si), −0.38 (E=Ge)) and a strongly negative NPA charge at the CVNL center of −1.00 ((1-Si)calc) and −0.89 ((1-Ge)calc), which in combination with the strongly positive NPA charge at the tetrel center (q(Si)=+1.38, q(Ge)=+1.23) points to a very polar E(δ+)−CVNL(δ−) bond. This is in line with the results of NRT analysis revealing a considerable ionic contribution (40 % ((1-Si)calc), 37 % ((1-Ge)calc)) to the total NRT bond order of the E−CVNL bond (NRT-BO: 2.0 ((1-Si)calc), 1.9 ((1-Ge)calc)) providing a rationale for the unusual shortening of the E=CVNL bond. Notably, q(CVNL) of (1-E)calc lies between the NPA charge of the central carbon atom in the carbodicarbene C(NHC)2 (NHC=C[N(Me)CH]2) (q(Ccent)=−0.50) and the carbodiphoshorane C(PMe3)2 (q(Ccent)=−1.47).63

3 Conclusion

Unprecedented NHC-supported 2-tetrelavinylidenes (NHC)C=EBr(R) (1-Si, 1-Ge, 1-GeMind: E=Si, Ge; NHC=C[N(Dipp)CH]2; R=bulky aryl group) were obtained highlighting the synthetic potential of the N-heterocyclic diazoolefin (NHC)CN2 as a C(NHC) vinylidene group transfer reagent. The compounds feature a planar 2-tetrelavinylidene core, an unusually short E=CVNL double bond, an ylidic CVNL−CNHC bond and a bent E−CVNL−CNHC skeleton undergoing easily linearization. Quantum chemical bonding analysis suggest a considerably bent 1-tetrelaallene and a cationic tetrelyne type character of the E−CVNL−CNHC bonding. Variable temperature NMR studies shed light into the stereodynamics of 1-E involving a NHC-rotation around the CVNL−CNHC bond with a low activation barrier. The synthetic potential of 1-E was demonstrated by the isolation and characterization of the first NHC-supported bromogermynes BrGe=C(EBr2Tbb)(IDipp) (2-EGe, E=Si, Ge). Compounds 1-E and 2-EGe contain reactive E−CVNL and E−Br bonds, offering up many reaction pathways that are currently under investigation in our laboratory.

4 Supporting Information

The ESI contains the syntheses, spectroscopic and analytical data, illustrations of the 1H NMR, 13C{1H} NMR and 29Si{1H} NMR spectra, dynamic NMR spectroscopic studies, crystallographic data, structure refinement parameters, and details of the quantum chemical calculations of 1-Si−2-GeGe (PDF) as well as the UV/Vis spectroscopic studies of 1-Si and 1-Ge.

Cartesian coordinates of the calculated structures (.txt)

Deposition Numbers 2322274 (for 1-Si), 2322275 (for 1-Ge), 2322276 (for 1-GeMind), 2322277 (for 2-SiGe), 2322278 (for 2-GeGe) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität Bonn for the financial support of this work. We are very grateful to the Fonds of the Chemical Industry (FCI) for the financial support of L.R.M. with a Kekulé Fellowship. We also thank Mrs. Kühnel-Lysek, Mrs. Hannelore Spitz, Dipl.-Ing. Karin Prochnicki and Mrs. Charlotte Rödde for technical support. We thank Dr. S. Nozinovic for helpful discussions on the dynamic NMR studies. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of the article.