The Relationship between Framingham Stroke Risk Profile on Incident Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease: A 40-Year Follow-Up Study Highlighting Female Vulnerability

Abstract

Objective

Sex differences in the association between cardiovascular risk factors and the incident all-cause dementia and the subtype Alzheimer's disease (AD) risk are unclear.

Methods

Framingham Heart Study (FHS) participants (n = 4,171, 54% women, aged 55 to 69 years) were included at baseline and followed up to 40 years. The Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP) was dichotomized into 2 levels (cutoff: 75th percentile of the FSRP z-scores). Cause-specific hazard models, with death as a competing event, and restricted mean survival time (RMST) model were used to analyze the association between FSRP levels and incident all-cause dementia and AD. Interactions between FSRP and sex were estimated, followed by a sex-stratified analysis to examine the sex modification effect.

Results

High FSRP was significantly associated with all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.25, robust 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.21 to 1.29, p < 0.001) and AD (HR = 1.58, robust 95% CI = 1.57 to 1.59, p < 0.001) in cause-specific hazard models. High FSRP was significantly associated with incident dementia (HR = 2.81, robust 95% CI = 2.75 to 2.87, p < 0.001) and AD (HR = 2.96, robust 95% CI = 2.36 to 3.71, p < 0.001) in women, but not in men. Results were consistent in the RMST models. Current diabetes and high systolic blood pressure as FSRP components were significantly associated with dementia and AD in women but not in men.

Interpretation

High FSRP in mid- to early late life is a critical risk factor for all-cause dementia and AD, particularly in women. Sex-specific interventions and further research to elucidate underlying mechanisms are warranted. ANN NEUROL 2024;96:1124–1134

The Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP) is a composite score that uses several critical cardiovascular risk factors to calculate the risk of the 10-year probability of incident stroke.1-3 The FSRP has been widely used as a comprehensive measure of vascular burden detrimental to the brain. Previous studies found a high FSRP associated with worse cognitive function in multiple domains,4-10 smaller brain volume,11, 12 and more extensive white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume.13

A recent Framingham Heart Study (FHS) publication linked age-specific vascular risk factors in FSRP with a 10-year risk of incident dementia. These findings offer valuable public health insights for potential preventive strategies and age-specific risk assessments.14

Given that previous studies suggest women have a higher lifetime risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer's disease (abbreviated as “dementia/AD” hereinafter),15 it remains unclear whether this sex difference is primarily due to selective survival bias16 or other sex-specific mechanisms and risk factors. Sex differences in the impact of vascular risk factors on incident dementia may play a critical role. For example, in postmenopausal women, the decline of the circulating estrogen leads to diminished protection against adiposity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and regulation of energy intake and expenditure, which may result in a metabolically compromised phenotype.17 Furthermore, investigating the sex-specific effects of vascular risk factors on incident dementia/AD is crucial, as these factors are potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia/AD,18, 19 and their prevalence varies between sexes.20 This research could help inform studies on the mechanisms and enable the development of sex-specific precision medicine approaches. Therefore, this study investigated the sex-specific association between mid to early late life FSRP and incident dementia/AD with a longitudinal follow-up of up to 40 years.

Methods

Participants and Study Design

The FHS study design and protocols have been described in greater detail in previous publications.21-23 The study began in 1948 by recruiting residents in Framingham, Massachusetts, who formed the Original Cohort of 5,209 participants.21 In 1971, the Offspring Cohort (N = 5,124) was established by inviting the children of the Original Cohort and their spouses to participate. FHS participants have been followed for incident dementia until the date of death after establishing dementia-free status. A total of 4,171 FHS Original and Offspring participants aged 55 to 69 years (mean ± standard deviation [SD] age = 58.8 ± 3.7) who had their first FSRP measurement in a health examination conducted after 1979, formed the baseline cohort for the present analysis. The age range was selected because the FSRP score was developed using subjects aged 55 years and older. In addition, we focused on the middle to early old age life stage to identify modifiable risk factors. The study excluded participants with a history of dementia or clinical stroke before or at baseline, missing follow-up cognitive status data, or less than 3 years of follow-up time (Supplementary Fig S2). Time-to-event data, including death and incident dementia, were collected from the baseline examination up to 40 years, through 2018.

Framingham Stroke Risk Profile

The construction of the revised FSRP algorithm (version 2017) for each sex included age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), use of antihypertensive therapy, diabetes mellitus (DM), cigarette smoking, prior cardiovascular disease (CVD), and atrial fibrillation (AF).3 The 2017 FSRP calculation details were described previously3 and briefly summarized in Supplementary Data S1 eMethods.

Case Ascertainment of Dementia and Subtypes

We included results from systematic surveillance for incident dementia since 1976. Details of these methods and procedures have been reported elsewhere.23-25 In brief, the cognitive evaluation methods and procedures for determining dementia and dementia subtypes for each participant included a thorough review of all available clinical data, neuropsychological (NP) test results, information from medical records, family interviews, neurological examinations, FHS health examinations, and stroke adjudication. The FSRP score was not used during the review, and the consensus review panel does not generally consider vascular risk factors in their diagnosis process to avoid circularity. A panel including at least one neurologist and one neuropsychologist determined cognitive status and identified (where applicable) the onset date of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. The diagnosis of dementia was established using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria26 and AD was diagnosed according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria.27

Ethics Approval and Consent

The study procedures and protocols were approved by the Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board (IRB), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for observational studies were followed.28

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. Because FSRP is known to increase with age, FSRP scores were log-transformed to reduce skewness and normalize the distribution and further rescaled as z-scores (mean = 0, SD = 1) at each age (year) to ensure comparability across baseline age (55–69 years). FSRP scores were dichotomized into high (FSRP ≥ 75th percentile [Q3] of z-score) and low (FSRP < Q3 of z-score) groups for comparison. This categorization of the high FSRP group was based on the dose–response curve, which revealed a crossover effect in the effect size of dementia/AD and mortality at this specific cutoff value in women (Supplementary Fig S3).

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 4,171) | Male (n = 1926) | Female (n = 2,245) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSRP (%)a | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 2.7 | 3.6 ± 3.4 | 1.8 ± 1.7 | < 0.001 |

| Median (range) | 3.1 (0.5 to 28.6) | 2.5 (0.6 to 28.6) | 1.2 (0.5 to 19.0) | - |

| FSRP ≥ Q3, No. (%)b | 1,043 (25) | 870 (45) | 173 (8) | < 0.001 |

| FSRP componentsc | ||||

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 58.8 ± 3.7 | 58.6 ± 3.6 | 58.9 ± 3.8 | 0.004 |

| Sex: F, No. (%) | 2,245 (54) | - | - | - |

| SBP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 129 ± 17 | 130 ± 16 | 128 ± 18 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension treatment, No. (%) | 1,116 (27) | 540 (28) | 576 (26) | 0.09 |

| Smoking, No. (%) | 826 (20) | 360 (19) | 466 (21) | 0.100 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 273 (7) | 164 (9) | 109 (5) | < 0.001 |

| CVD, No. (%) | 324 (8) | 212 (11) | 112 (5) | < 0.001 |

| AF, No. (%) | 81 (2) | 57 (3) | 24 (1) | < 0.001 |

| APOE ε4 carrier, No. (%) | 932 (22) | 415 (22) | 517 (23) | 0.27 |

| Education, No. (%) | ||||

| No high school | 405 (10) | 206 (11) | 199 (9) | < 0.001 |

| High school graduate | 1,383 (33) | 582 (30) | 801 (36) | |

| Some college | 1,130 (27) | 433 (22) | 697 (31) | |

| College | 1,253 (30) | 705 (37) | 548 (24) | |

| Postmenopaused | ||||

| No. (%) | - | - | 2,158 (96) | - |

| Age at menopause, mean ± SD (y) | - | - | 47.8 ± 6.3 | |

| Hormone usaged | ||||

| No. (%) | - | - | 616 (27) | - |

- P values were compared between 2 sex groups (female vs male) using a t test for continuous variables and a Chi-square (χ2) test for category variables.

- a FSRP = 10-year stroke risk (%).

- b Q3 is the 75th percentile of z-score of the log-transformed FSRP of each age (y).

- c The individual risk factors that comprise the Revised Framingham Stroke Risk Profile.3

- d Postmenopause and hormone usage only summarized in women and hormone usage including estrogen and Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs), where the majority were estrogen usage and only 15 cases reported using SERMs in this table.

- AF = atrial fibrillation; CVD prior = cardiovascular disease; FSRP = Framingham Stroke Risk Profile; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

A cause-specific hazard model was used to investigate the association between FSRP and dementia/AD incidence for up to 20 years of follow-up, considering death as a competing risk (Table 2). Multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, education category, APOE ε4 carrier status, FHS cohort generation (model 1); FHS generation was controlled to test for cluster effects and provide a robust 95% CI (model 2). The model was constructed within 20 years of follow-up because the proportional hazards assumption was not met beyond this period (Supplementary Table S1, the global proportional hazards test failed beyond 20 years).29

| Strata and events | Total (No.) | Events (No.) | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR [95% CI] | p | Sig. | HR [robust 95% CI] | p | Sig. | |||

| All participants | ||||||||

| Dementia | 4,171 | 248 | 1.25 [0.91 to 1.73] | 0.17 | 1.25 [1.21 to 1.29] | < 0.001 | *** | |

| AD | 4,024 | 174 | 1.57 [1.06 to 2.32] | 0.03 | * | 1.58 [1.57 to 1.59] | < 0.001 | *** |

| Interaction modelc | ||||||||

| Event = dementia | 4,171 | 248 | ||||||

| FSRP main effect | 0.25 [0.10 to 0.61] | 0.002 | ** | 0.25 [0.15 to 0.41] | < 0.001 | *** | ||

| Sex main effect | 0. 71 [0.52 to 0.96] | 0.024 | * | 0.70 [0.64 to 0.78] | < 0.001 | *** | ||

| FSRP * F | 3.34 [1.83 to 6.11] | < 0.001 | *** | 3.32 [2.60 to 4.24] | < 0.001 | *** | ||

| Event = AD | 4,024 | 174 | ||||||

| FSRP main effect | 0.35 [0.11 to 1.07] | 0.060 | 0.36 [0.12 to 1.08] | 0.070 | ||||

| Sex main effect | 0.93 [0.63 to 1.37] | 0.71 | 0.92 [0.73 to 1.17] | 0.51 | ||||

| FSRP * F | 2.90 [1.41 to 5.97] | 0.004 | ** | 2.83 [1.46 to 5.48] | 0.002 | ** | ||

| Strata by sex | ||||||||

| F | ||||||||

| Dementia | 2,245 | 139 | 2.82 [1.78 to 4.46] | < 0.001 | *** | 2.81 [2.75 to 2.87] | < 0.001 | *** |

| AD | 2,176 | 109 | 2.97 [1.76 to 5.00] | < 0.001 | *** | 2.96 [2.36 to 3.71] | < 0.001 | *** |

| M | ||||||||

| Dementia | 1,926 | 109 | 0.83 [0.56 to 1.23] | 0.35 | 0.83 [0.63 to 1.11] | 0.21 | ||

| AD | 1,848 | 65 | 1.04 [0.63 to 1.73] | 0.87 | 1.07 [0.67 to 1.69] | 0.78 | ||

- The cause-specific hazard of a given event (eg, dementia/AD) can be determined in the traditional time-to-event model, where the event of interest is counted as an event and any competing events are censored at the date they occur. When death without dementia is considered as the competing risk, Cox regression models were applied to the all participants or stratified by sex, using dementia and AD as time-to-event outcomes within a 20-year follow-up period, respectively. The predictor variable was the higher FSRP level (FSRP ≥ Q3 versus FSRP < Q3), where Q3 represented the 75th percentile quantile z-score of the log-transformed FSRP for each age (year).

- The time-to-event outcomes were followed up to 20 y, and the results were analyzed using the Cox models with the following formula: model = coxph (Surv(time = follow-up time, event = events) ~ FSRP + sex + baseline age + other covariates, cluster = generation).

- a Model 1 was adjusted for sex, age, education, APOE ε4 currier status, and FHS generation.

- b Model 2 Model 1 + control FHS generation as cluster effect by set cluster = FHS generation, which provided robust 95% CI.

- c Model 1 and Model 2 added interaction effects between FSRP group and female sex in the above model 1 and model 2, respectively.

- Significant (Sig.) codes: * p value < 0.05, ** p value < 0.01, *** p value < 0.001.

- 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; AD = Alzheimer's disease; F = female; FHS = Framingham Heart Study; FSRP = Framingham Stroke Risk Profile; HR = hazard ratio; M = male.

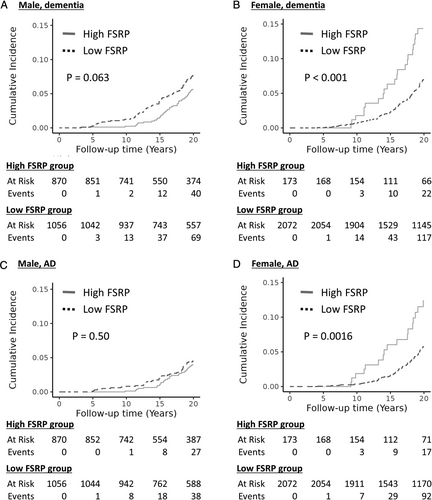

The interaction effects of FSRP and sex were explored in the cause-specific hazard model and found to be statistically significant (see Table 2). The interaction effects of FSRP and sex were consistently significant in the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model, which is another approach for considering the competing risks of death (Supplementary Table S2). Therefore, sex-stratified analyses were further conducted to study sex differences by fitting separate models for men and women using the cause-specific hazard model (see Table 2). The sex-stratified cumulative incidence of dementia/AD between FSRP groups is illustrated in Figure 1, adjusted for the competing events of non-dementia death using the cuminc function from the tidycmprsk R software package. The sensitivity analysis was conducted in the subset of postmenopausal women, age at menopause and hormone treatment (self-reported) were further controlled in the above models.

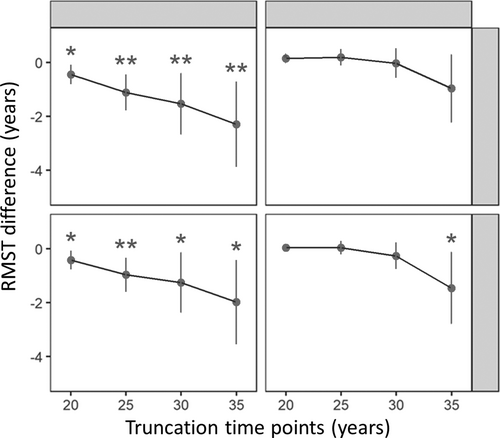

To assess the association beyond 20 years, we applied the restricted mean survival time (RMST) method, which has been suggested as an alternative measure when the assumption of the proportional hazards model are not met.30 RMST is similar to the mean survival time but is restricted by a specified time point (T). Four truncation time points (T20, T25, T30, and T35) were defined for 20, 25, 30, and 35 years in the RMST analysis. Specifically, we compared the differences in survival time between the 2 FSRP groups at each time point in this study (Table 3 and Fig 2). The negative beta value in the RMST model indicates a shorter survival time between FSRP groups. This measure can be interpreted as the average differences in survival time or life expectancy between groups during a defined period, which provides a straightforward and clinically meaningful way to compare survival between groups.

| Event | Time year (T) | F (n = 2,245) | M (n = 1926) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events (No.) | Beta [95% CI] | p | Sig. | Events (No.) | Beta [95% CI] | p | Sig. | ||

| Dementia | |||||||||

| 20 | 139 | −0.45 [−0.80 to −0.09] | 0.02 | * | 109 | 0.16 [−0.01 to 0.32] | 0.06 | ||

| 25 | 257 | −1.11 [−1.78 to −0.45] | 0.001 | ** | 169 | 0.20 [−0.10 to 0.50] | 0.20 | ||

| 30 | 327 | −1.55 [−2.69 to −0.42] | 0.007 | ** | 211 | −0.02 [−0.57 to 0.53] | 0.94 | ||

| 35 | 360 | −2.33 [−3.92 to −0.73] | 0.004 | ** | 228 | −0.96 [−2.22 to 0.30] | 0.14 | ||

| AD | |||||||||

| 20 | 109 | −0.42 [−0.77 to −0.07] | 0.02 | * | 65 | 0.03 [−0.09 to 0.16] | 0.60 | ||

| 25 | 210 | −0.98 [−1.62 to −0.35] | 0.003 | ** | 109 | 0.03 [−0.22 to 0.28] | 0.83 | ||

| 30 | 263 | −1.28 [−2.40 to −0.17] | 0.02 | * | 136 | −0.27 [−0.76 to 0.23] | 0.29 | ||

| 35 | 291 | −2.02 [−3.59 to −0.46] | 0.01 | * | 150 | −1.46 [−2.78 to −0.14] | 0.03 | * | |

- RMST models: (1) The predict variable was the high FSRP ≥ Q3 versus FSRP < Q3, where Q3 was the 75% quantile z-score of the log transformed FSRP of each age (year). (2) Events were the incident dementia/AD within 40 years of follow-up. Beta is the RMST difference between FSRP groups at the 4 truncation time (T) points of 20, 25, 30, and 35 years (T20, T25, T30, and T35), respectively. A negative beta value indicates a shorter survival time (years). (3) All models adjusted age, sex, education, APOE4 and FHS generation.

- Significant (Sig.) codes: * p value < 0.05, ** p value < 0.01, *** p value < 0.001.

- 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; AD = Alzheimer's disease; F = female; FHS = Framingham Heart Study; FSRP = Framingham Stroke Risk Profile; M = male; RMST = restricted mean survival time.

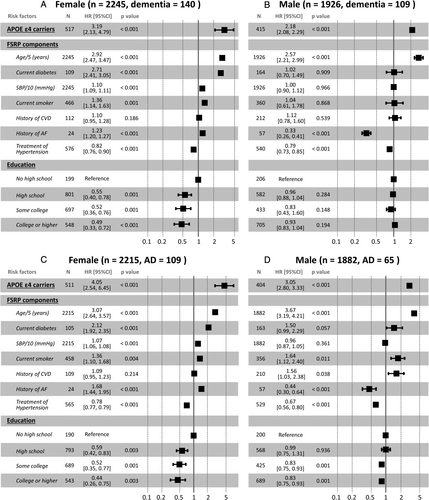

Finally, the cause-specific hazard models were conducted to evaluate the association between components of FSRP and the onset of dementia/AD, which served the dual purpose of validating the robustness of the FSRP association and identifying modifiable risk factors that could be potential targets for disease control (Fig 3). All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.0), a language and environment for statistical computing.31 The statistical significance level was set at p = 0.05 (2-tailed).

Results

The cohort (n = 4,171) included middle-aged and older participants at the baseline (mean ± SD age = 58.8 ± 3.7 years, range = 55 to 69 years, 54% women). The median baseline FSRP raw score was 3.1% (men = 2.5% vs women = 1.2%). The proportion of high FSRP (≥ Q3) was significantly higher in men (45%) than in women (8%). Among women, 96% were postmenopausal at a mean age of menopause 47.8 years, and 27% of women reported hormone usage. During follow-up, a total of 591 (14%) participants had incident all-cause dementia, with 444 (11%) cases being AD. The cumulative incidences of dementia and AD were significantly higher in women (16% for dementia and 13% for AD) than men (12% for dementia and 8% for AD). AD accounted for 75.1% cases of all-cause dementia; the proportion was 65.7% in men and 81.0% in women.

In the cause-specific hazard model (see Table 2), high FSRP was significantly associated with an increased incidence of all-cause dementia (HR = 1.25, robust 95% CI = 1.21 to 1.29, p < 0.001) and AD (HR = 1.58, robust 95% CI = 1.57 to 1.59, p < 0.001) within 20 years of follow-up. In addition, we found that the interaction of FSRP and sex was significantly associated with the incidence of all-cause dementia (HR = 3.32, robust 95% CI = 2.60 to 4.24, p < 0.001) and AD (HR = 2.83, robust 95% CI = 1.46 to 5.48, p = 0.002; see Table 2). This interaction remained consistent in the Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard models, evidenced by a subdistribution hazard ratio (sHR) of 3.12 (95% CI = 1.59 to 6.14, p < 0.001) for all-cause dementia and a sHR of 2.48 (95% CI = 1.06 to 5.83, p = 0.04) for AD over a 20-year follow-up period; results were consistent for up to 40 years’ follow-up (see Supplementary Table S2).

In the sex-stratified analysis (see Table 2), high FSRP was significantly associated with an increased incidence of dementia (HR = 2.81, robust 95% CI = 2.75 to 2.87, p < 0.001) and AD (HR = 2.96, robust 95% CI = 2.36 to 3.71, p < 0.001) in women. No significant associations were observed in men. In the sensitivity analysis in the subset of postmenopausal women, results were consistent for dementia (HR = 2.58, robust 95% CI = 2.23 to 3.00, p < 0.001) and AD (HR = 2.64, robust 95% CI = 2.39 to 2.91, p < 0.001), after controlling for age at menopause and hormone treatment.

Table 3 shows the differences in survival time between the 2 FSRP groups at each truncation time point of T20, T25, T30, and T35 during up to 40 years of follow-up. Women with high FSRP had earlier onset of dementia by 0.45 years (beta = −0.45, 95% CI = −0.80 to −0.09, p = 0.02) and earlier onset of AD by 0.42 years (beta = −0.42, 95% CI = −0.77 to −0.07, p = 0.02) than those with low FSRP at the 20-year truncation time point (T20) in the RMST model. Consistent with the 20-year findings, high FSRP remained significantly associated with earlier incident dementia/AD in women at truncation time points T25, T30, and T35 (see Table 3). Specifically, at these time points, women with high FSRP had earlier onset of dementia by 1.11, 1.55, and 2.33 years and earlier onset of AD by 0.98, 1.28, and 2.02 years, respectively, compared with women in the low FSRP group. The results also indicate a cumulative dose–response effect between two groups (FSRP ≥ Q3 vs FSRP < Q3) across cumulative follow-up time at all 4 truncation points, especially in women, with the largest difference observed at the 35-year truncation time point (see Fig 2), suggesting that high FSRP may be a risk factor for earlier onset of dementia/AD in women. However, high FSRP was only significantly associated with earlier incident AD at the truncation time point of 35 years in men.

As shown in Figure 3, among the modifiable components of FSRP, current diabetes was significantly associated with incident all-cause dementia (HR = 2.71, robust 95% CI = 2.41 to 3.05, p < 0.001) and AD (HR = 2.12, robust 95% CI = 1.92 to 2.35, p < 0.001) in women but not in men (see Fig 3). In addition, with increasing age, high SBP, diabetes, smoking, and a history of AF were significantly associated with a higher risk of incident dementia/AD in women, and antihypertensive treatment was associated with a lower risk of incident dementia/AD in both women and men. Current smoking and history of CVD were associated with AD but not all-cause dementia in men. Although education is not included in the FSRP, a higher level of education was found to have a significant protective effect against both dementia/AD and all-cause mortality, especially in women.

Discussion

Population-based research investigating the sex modification effect on the association between vascular risk factors and incident dementia/AD is limited, with mixed results.32-34 The population-based UK Biobank data reported that the dementia risk in women tended to increase with SBP, whereas there was a U-shaped relationship for men. The risks were similar for current smoking, diabetes, high adiposity, prior stroke, and low socioeconomic status between the sexes.32 A Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) study found that midlife hypertension was associated with dementia risk only in women, although hypertension was more common in men.33 A meta-analysis of results from 14 studies did not find a sex difference in the association between diabetes and dementia risk.34 Methodological differences, such as the study population, data collection methods, and case ascertainment strategies, may explain these inconsistent results. In addition, these studies examined dementia risk and individual vascular risk factors between sexes rather than a composite score. By contrast, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to apply the widely used FSRP composite score to assess sex differences in the relationship between vascular risk burden and dementia/AD. In addition, we also examined each component of FSRP. Results consistently found sex differences. The study results also capitalized on FHS’ rigorous methodology, which includes the uniquely long period of follow-up, systematic data collection with rigorous quality control, and consistency in diagnosis of dementia/AD outcome by consensus review.

The lifetime risk of AD has been reported to be higher for women than men.35 Although the underlying reasons for the sex difference remain elusive, the sex-specific biological mechanisms have been explored as an essential adjunct explanation to longevity for women. Potential determinants may include sexual dimorphism in brain structure, sex hormone signaling, risk genes and sex interactions, immune modulation, and vascular disorders.36 Among these possible mediators, vascular risk factors are modifiable and positively associated with cerebral vascular disease and neurodegeneration.18 Our findings suggest sex differences in the impact of vascular risk factors on brain pathological and pathophysiological mechanisms underlying dementia/AD. There is evidence showing that women are more vulnerable to vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies, which can lead to chronic cognitive decline.37 For instance, the Rotterdam Scan Study observed that female sex was associated with more significant small vessel disease (SVD) progression.38 The multicenter Swiss Atrial Fibrillation study found that among 1,743 patients with AF (27% women), women had a higher white matter disease burden than men.39 Whereas vascular risk factors are common (and often more common) in men, women disproportionately have SVD, as demonstrated by postmortem data from the Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project (ROSMAP) study showing that women were more likely to have more severe arteriolosclerosis, higher levels on a global measure of AD pathology, and greater tau tangle density.40 In addition, there is evidence suggesting that women are more susceptible to neurodegenerative tau pathology, which contributes to a greater risk of faster cognitive decline,41, 42 and tau has been recently reported to mediate the synergistic influence of vascular risk and β-amyloid on cognitive decline.43 However, evidence suggests that women may have greater cognitive resilience than men, but this is controversial.44, 45 These conflicting findings suggest that more research is needed to investigate the complex interplay between neurobiological mechanisms and vascular risk factors contributing to sex-specific vulnerability to dementia/AD.

In our analysis, results were consistent in the subset of the postmenopausal women, even after controlling for hormone usage. The impact of estrogen on the risk of cognitive decline and dementia remains unclear.46 Estrogen affects biochemical receptors and neurotransmitters in the brain and acts as a mild vasodilator that enhances blood flow within the brain.17 The effects of estrogen are reduced in postmenopausal women, who are more susceptible to vascular risk factors.17 However, studies of the association of estrogen therapy (ET) given to postmenopausal women with the risk of cognitive decline and dementia have yielded inconsistent findings.46 Before 2014, ET was deemed beneficial to the brain when initiated early after menopause.46 However, a 2019 Finnish study reported that ET was associated with an increased risk of AD in women.47 Therefore, the contribution of estrogen to the observed sex difference in dementia/AD is still uncertain.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Some sex-specific findings may be explained by survival bias due to the higher mortality rate in men attributable to the association of higher FSRP with an increased risk of death. To address this issue, we constructed the competing risk models (cause-specific hazard model and Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard model) to account for the death effect. The results were largely consistent except that high FSRP was significantly associated with earlier incident AD but not all-cause dementia in men at the truncation time point of 35 years in the RSMT model. We believe this varied association may be influenced by mixed etiologies, the competing risk of death, or residual confounding, which may have changed over the long follow-up period. Additionally, although the association with all-cause dementia in the RMST model at 35 years was not significant, the trend still suggests a similar direction of effect and does not affect the validity of our main findings.

The proportion of women with an FSRP in the top quartile was much lower than in men. To evaluate that our results were not affected by the unintentional selection bias of women with higher risk than men, we did an additional sensitivity analysis using the same high percentile proportion as the cutoff for each sex and the results were consistent. Moreover, FSRP was derived using separate formulas for men and women, thus we also explored different cutoff FSRP values (ranging from the 10th to the 90th percentile) for both men and women, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig S3. Our analysis indicates that women have peak risk at the 82nd percentile, which was not observed in men. This information supports that “relatively” high levels of FSRP within each sex group are differentially associated with different dementia risks.

Other limitations are the FHS cohort, in which most participants self-identified as non-Hispanic White, and the origin of all participants is a single city in Massachusetts. Therefore, the results may not generalize to other populations with different racial/ethnic and geographic characteristics. Thus, further studies with more diverse population are need to determine the generalizability of these results. Moreover, there might be a possibility of misclassification bias due to the inclusion individuals with mild dementia at baseline. We attempted to minimize the impact of this bias by excluding participants whose dementia onset occurred within 3 years of the baseline examination. This criterion was based on our previous finding that the average transition time from mild cognitive impairment to mild dementia is approximately 2.3 years.48

In summary, the findings of this study suggest that high FSRP in middle to late adulthood is a critical risk factor for dementia/AD, particularly in women. Further research is needed to elucidate mechanisms underlying the sex difference in the associations.

Acknowledgments

The thank to the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) participants for their decades of dedication and the FHS staff for their hard work collecting and preparing the data. This work was supported by the Framingham Heart Study's National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contract (N01-HC-25195; 75N92019D00031), and NIH grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG008122, AG016495, AG054156, AG049810, AG062109, and AG068753).

Author Contributions

R.A., J.Y., Q.T., and A.A. contributed to the conception and design of the study. Q.T., A.A., C.L., S.D., S.A., J.M., L.F., W.Q., and R.A. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. J.Y. and Q.T. contributed to drafting the text or preparing the figures.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

R.A. is a scientific advisor to Signant Health and NovoNordisk. No other authors have anything to report.

Open Research

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript can be made available upon request pending application to and approval by the Framingham Heart Study. Please refer to the instructions on the website: https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/fhs-for-researchers/.