Polypharmacy and cumulative anticholinergic burden in older adults hospitalized with fall

Ho Lun Wong and Claire Weaver should be considered joint first authors.

Abstract

Introduction

Polypharmacy is a growing phenomenon associated with adverse effects in older adults. We assessed the potential confounding effects of cumulative anticholinergic burden (ACB) in patients who were hospitalized with falls.

Methods

A noninterventional, prospective cohort study of unselected, acute admissions aged ≥ 65 years. Data were derived from electronic patient health records. Results were analyzed to determine the frequency of polypharmacy and degree of ACB and their relationship to falls risk. Primary outcomes were polypharmacy, defined as prescription of 5 or more regular oral medications, and ACB score.

Key Results

Four hundred eleven (411) consecutive subjects were included, mean age 83.8 ± 8.0 years: 40.6% men. There were 38.4% patients who were admitted with falls. Incidence of polypharmacy was 80.8%, (88.0% and 76.3% among those admitted with and without fall, respectively). Incidence of ACB score of 0, 1, 2, ≥ 3 was 38.7%, 20.9%, 14.6%, and 25.8%, respectively. On multivariate analysis, age [odds ratio (OR) = 1.030, 95% CI:1.000 ~ 1.050, P = 0.049], ACB score (OR = 1.150, 95% CI:1.020 ~ 1.290, P = 0.025), polypharmacy (OR = 2.140, 95% CI:1.190 ~ 3.870, P = 0.012), but not Charlson Comorbidity Index (OR = 0.920, 95% CI:0.810 ~ 1.040, P = 0.172) were significantly associated with higher falls rate. Of patients admitted with falls, 29.8% had drug-related orthostatic hypotension, 24.7% had drug-related bradycardia, 37.3% were prescribed centrally acting drugs, and 12.0% were taking inappropriate hypoglycemic agents.

Conclusion

Polypharmacy results in cumulative ACB and both are significantly associated with falls risk in older adults. The presence of polypharmacy and each unit rise in ACB score have a stronger effect of increasing falls risk compared to age and comorbidities.

Abbreviations

-

- CCI

-

- Charlson Comorbidity Index

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- ACB

-

- anticholinergic burden

What Is Already Known

- Polypharmacy is very common in adults over 65 years of age and its prevalence is increasing.

- It is associated with numerous adverse outcomes including hospitalization with fall.

- Many commonly prescribed medications have anticholinergic properties.

- Cumulative anticholinergic burden (ACB) may explain a proportion of the poor outcomes associated with polypharmacy.

What this Study Adds

- To our knowledge, our study is the first that investigates the link between polypharmacy and falls by stratifying into several plausible culprit mechanisms under the umbrella of polypharmacy.

- Our study shows an increased risk of falls per unit increase of ACB score, which is previously unreported.

- Patients with a calculated ACB score of 3 compared to those with ACB score of 0 have a > 50% higher falls risk.

- Common adverse effects of polypharmacy also included orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, and hypoglycemia.

- Our data demonstrate that falls are strongly associated with polypharmacy rather than comorbidity, suggesting that a significant proportion of falls are iatrogenic and preventable.

Clinical Significance

- Structured medication review of all patients presenting with fall, with a focus on reducing ACB, is likely to reduce some of the burden of falls on the health care system.

- Routinely calculating ACB scores in inpatients aged over 65 years may assist with medication rationalization and deprescribing.

- Medical professionals at all levels would benefit from further education regarding the implications of polypharmacy and the need to weigh the benefit of a new medication with the associated harms of increased medication and ACB.

1 INTRODUCTION

The most widely recognized definition of polypharmacy is the use of five or more medications.1, 2 The high prevalence of polypharmacy is a consequence of the increasing rate of multimorbidity in the aging population worldwide. In the United Kingdom, up to one third of 69-year-olds are prescribed polypharmacy.3 Polypharmacy is associated with several negative outcomes, including adverse drug effects, nonadherence, and functional decline.4, 5

The risk of hospitalization with falls increases with polypharmacy. Fall is one of the most common reasons for admission to hospital for older adults and are to is a main cause of morbidity with an in-hospital mortality rate as high as 16%.6, 7

Polypharmacy predisposes to higher anticholinergic burden (ACB), which is emerging as a risk factor for adverse events that disproportionately affect older adults, including falls, cognitive impairment, and progression of neurodegenerative disease.8-12 Many medications used to treat chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, depression, urinary incontinence, pain, and allergies, have weak anticholinergic properties, but the summative effects may have important implications and worse outcomes in older adults.

The aim of our study was to assess the incidence of polypharmacy among older hospitalized patients and to explore the relationship between polypharmacy, cumulative ACB and risk of hospital admission due to falls.

2 METHODS

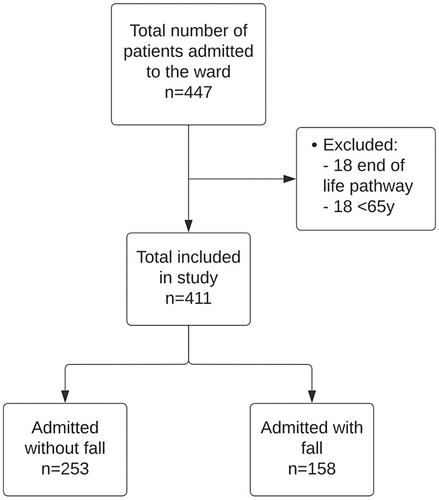

This was a noninterventional prospective cohort study of all elderly patients defined as aged ≥ 65 years admitted to an acute medical ward of a district general hospital based in southern England between September 2021 and November 2021. All patients admitted onto the ward above the age of 65 years were included. Patients who were below the age of 65 years and for end-of-life care were excluded. Data from consecutive patients were collected from the electronic patient health records. Data set included age, gender, medical history, medications, documentation of falls, and nursing observation charts, including heart rate and postural blood pressure readings. Figure 1 shows the patient inclusion flowchart. This study was approved by our institution's Research, Quality Improvement and Audit Department with reference FXP-48.

Pharmacological reconciliation was carried out by hospital pharmacists utilizing the national patient database: NHS Summary Care Record which contains all regular and acute medication prescriptions. All regular oral medications prior to admission were included for this study and polypharmacy was defined as greater than or equal to five regular medications. The ACB score was calculated using an online based ACB calculator (accessible on http://www.acbcalc.com/). Each medication was assigned a score of 0 for no anticholinergic properties; 1 for mild anticholinergic properties; 2 for moderate; and 3 for severe. The total ACB score was therefore the sum of scores for all regular medications on admission.

Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated based on each patient's medical history as listed on their electronic patient records. Patient age and medical history were used for CCI calculation. Aspects of medical history used for CCI calculation included myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebral vascular accident/transient ischemic attack, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, hemiplegia, moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (stage ≥3), solid tumor, leukemia, lymphoma, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. An online CCI calculator was used to calculate each patient's CCI, accessible on https://www.mdcalc.com/charlson-comorbidity-index-cci.

The primary outcomes of the study were to identify the incidence of polypharmacy and ACB scores, comparing this between hospitalized older adults admitted with or without a fall, and to investigate the association among falls, ACB score, CCI, and age. The secondary outcome of the study was to identify the incidence of drug-related orthostatic hypotension (defined as a fall in systolic blood pressure of at least 20 mm Hg and/or a fall in diastolic blood pressure of at least 10 mm Hg within 3 minutes of standing), drug-related bradycardia (defined as a heart rate of less than 60 beats per minute on 2 or more occasions during the daytime [nocturnal bradycardic episodes were not deemed significant], which was reversible on cessation of negatively chronotropic agents), prescription of centrally acting and inappropriate doses, or prescription of hypoglycemic agents in patients admitted with a fall.

2.1 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the online medical statistics application EasyMedStat (version 3.17; www.easymedstat.com). The data presented as mean with standard deviation and categorical variables were shown as percentages. A multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess the relation between falls and ACB score, CCI, and age. Odds ratio (OR) was adjusted for different sets of confounders and are reported with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Data were checked for multicollinearity with the Belsley-Kuh-Welsch technique. Heteroskedasticity and normality of residuals were assessed, respectively, by the White test and the Shapiro–Wilk test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

A total of 411 patients were included in the study. The mean age of our patients was 83.8 ± 8.0 years, and 40.6% were men. Table 1 summarizes patient demographics and characteristics. There were 38.4% of our patients who were admitted with a fall. The median age was 86.0 (Q1 79.0 and Q3 90.0) and 84.0 years (Q1 78.0 and Q3 90.0), respectively, for patients admitted with and without a fall (D: 2.0, P = 0.125; Tables 2a and 2b for univariate and bivariate analysis). Age was associated with an increased rate of patients admitted with a fall per each 1-unit rise (OR = 1.030, 95% CI:1.000 ~ 1.050, P = 0.049).

| Mean ± standard deviation | Percentage of total, % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 83.3 ± 8.0 | – |

| Gender (male) | 40.6 | |

| CCI | 5.7 ± 1.7 | – |

| Polypharmacy | – | 78.3 |

| Admitted with a fall/history of falls | – | 38.4 |

| Past medical history | ||

| Dementia/cognitive impairment | 25.6 | |

| Stroke | 15.1 | |

| Parkinson's disease | 5.1 | |

| Hypertension | 56.9 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 34.6 | |

| Heart failure | 27.3 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 12.4 | |

| Asthma | 11.2 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 16.3 | |

| Diabetes | 27.5 | |

| Chronic kidney disease (stage ≥ 3) | 28.5 | |

| Cancer | 18.7 | |

| Fragility fractures | 12.2 | |

| Statistics | Age, y |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 411 |

| Mean ± SD | 83.83 ± 7.98 |

| Min; max | 66.0; 102.0 |

| Median | 85.0 |

| Q1; Q3 (IQR) | 78.0; 90.0 (12.0) |

| Unknown (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Excluded (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Statistics | Admitted with fall | Not admitted with fall |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 158 | 253 |

| Mean ± SD | 84.54 ± 7.75 | 83.38 ± 8.1 |

| Min; max | 66.0; 98.0 | 66.0; 102.0 |

| Median | 86.0 | 84.0 |

| Q1; Q3 (IQR) | 79.0; 90.0 (11.0) | 78.0; 90.0 (12.0) |

The mean CCI of our study group was 5.7 ± 1.7. The mean CCI in patients admitted with and without a fall was 5.65 ± 1.66 and 5.74 ± 1.76, respectively. The median CCI were, respectively, 5.0 (Q1 5.0 and Q3 6.0) and 5.0 (Q1 5.0 and Q3 7.0) for patients admitted with and without fall (D: 0.0, P = 0.549; Tables 3a and 3b for univariate and bivariate analysis). CCI was not associated with the rate of patients admitted with a fall with each 1-unit rise (OR = 0.920, 95% CI:0.810 ~ 1.040, P = 0.172).

| Statistics | Charlson comorbidity index |

|---|---|

| N | 411 |

| Mean ± SD | 5.7 ± 1.72 |

| Min; max | 2.0; 12.0 |

| Median | 5.0 |

| Q1; Q3 (IQR) | 5.0; 7.0 (2.0) |

| Unknown (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Excluded (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Statistics | Admitted with fall | Not admitted with fall |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 158 | 253 |

| Mean ± SD | 5.65 ± 1.66 | 5.74 ± 1.76 |

| Min; max | 3.0; 11.0 | 2.0; 12.0 |

| Median | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Q1; Q3 (IQR) | 5.0; 6.0 (1.0) | 5.0; 7.0 (2.0) |

Overall incidence of polypharmacy of our study group was 80.8%. Polypharmacy in patients admitted without and with a fall were 76.3% and 88.0% respectively. There was an association between polypharmacy and an increased risk of fall (OR = 2.270, 95% CI: 1.300 ~ 3.980, P = 0.005); Tables 4a and 4b for univariate and bivariate analysis of polypharmacy). Table 5 lists commonly prescribed drugs (incidence > 5%) with ACB within our study group. Incidence of ACB scores of 0, 1, 2, and ≥ 3 was 38.7%, 20.9%, 14.6%, and 25.8%, respectively. The median ACB scores were, respectively, 2.0 (Q1 0.0 and Q3 3.0) and 1.0 (Q1 0.0 and Q3 2.0) for patients admitted with and without fall (D: 1.0, P = 0.009; Tables 6a and 6b for univariate and bivariate analysis of ACB score). ACB score was associated with an increased rate of patients admitted with a fall per each 1-unit rise in ACB (OR = 1.150, 95% CI:1.020 ~ 1.290, P = 0.025). In our linear regression model, a patient with an ACB score of 3 compared to a patient with an ACB score of 0 would have a > 50% higher chance of falling.

| Polypharmacy | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 332 | 80.78 |

| No | 79 | 19.22 |

| Total | 411 | 100 |

| Unknown values | 0 | |

| Excluded values | 0 |

| Variable | Fall: no | Fall: yes | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypharmacy: no |

60 23.72% |

75.95% 14.6% |

19 12.03% |

24.05% 4.62% |

79 | 19.22% |

| Polypharmacy: yes |

193 76.28% |

58.13% 46.96% |

139 87.97% |

41.87% 33.82% |

332 | 80.78% |

| Total | 253 | 61.56% | 158 | 38.44% | 411 | 100% |

| Medication | ACB score | Incidence of use (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Furosemide | 1 | 16.1 |

| Mirtazapine | 1 | 8.3 |

| Digoxin | 1 | 7.8 |

| Sertraline | 2 | 7.8 |

| Codeine | 1 | 6.6 |

| Citalopram | 1 | 6.3 |

| Warfarin | 1 | 6.1 |

| Amitriptyline | 3 | 5.4 |

| Isosorbide mononitrate | 1 | 4.4 |

| Morphine | 1 | 4.1 |

| Prednisolone | 1 | 4.1 |

| Olanzapine | 3 | 3.2 |

| Solifenacin | 3 | 2.9 |

| Trazodone | 1 | 2.7 |

| Diazepam | 1 | 2.4 |

| Co-Careldopa | 1 | 2.2 |

| Promethazine | 3 | 1.9 |

| Fluoxetine | 1 | 1.7 |

| Levomepromazine | 2 | 1.7 |

| Quetiapine | 1 | 1.7 |

| Tramadol | 1 | 1.7 |

| Risperidone | 1 | 1.5 |

| Co-codamol | 1 | 1.2 |

| Oxybutynin | 3 | 1.2 |

| Statistics | ACB score |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 411 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.53 ± 1.76 |

| Min; max | 0.0; 11.0 |

| Median | 1.0 |

| Q1; Q3 (IQR) | 0.0; 3.0 (3.0) |

| Unknown (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Excluded (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Statistics | Admitted with fall | Admitted without fall |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 158 | 253 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.82 ± 1.91 | 1.35 ± 1.64 |

| Min; max | 0.0; 11.0 | 0.0; 8.0 |

| Median | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Q1; Q3 (IQR) | 0.0; 3.0 (3.0) | 0.0; 2.0 (2.0) |

Of the patients who were admitted with fall (38.4% of total study group), 29.8% were found to have drug-related orthostatic hypotension, 24.7% had drug-related bradycardia, 37.3% were taking regular centrally acting agents, and 12.0% were taking inappropriate hypoglycemic agents. Table 7 summarizes the incidence of secondary outcomes in patients admitted with fall. Table 8 summarizes the regression results of the study.

| Admitted with/history of fall with: | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Orthostatic hypotension | 29.75 |

| Iatrogenic bradycardia | 24.68 |

| Centrally acting agents | 37.34 |

| Hypoglycemic agents | 12.03 |

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | value |

|---|---|---|

| Constant/intercept | 0.048 (0.005; 0.479) | 0.009** |

| Age (risk for each 1-unit rise) | 1.030 (1.000; 1.050) | 0.049* |

| Charlson comorbidity index (risk of each 1-unit rise) | 0.916(0.807; 1.040) | 0.172 |

| Polypharmacy (Y/N) | 2.140 (1.190; 3.870) | 0.012* |

| Acetylcholine burden score (risk for each 1-unit rise) | 1.150 (1.020; 1.290) | 0.025* |

- * P < 0.05.

- ** P < 0.01.

4 DISCUSSION

Polypharmacy is a common phenomenon in older adults and is associated with worse physical and cognitive outcomes, which may be aggravated by the summative effect of drugs carrying ACB. Our study, clearly demonstrates that age, ACB, polypharmacy, but not comorbidity, are associated with significantly higher falls risk in older patients.

Our results demonstrate a high incidence of polypharmacy in older hospitalized patients (78.3%) consistent with previous epidemiology studies (74%).13 Eighty-eight percent of patients admitted with a fall were exposed to polypharmacy. Our data highlight a statistically significant positive association between polypharmacy and cumulative ACB and the incidence of falls. Our data also show a higher OR between polypharmacy and falls compared to comorbidity. This implies that the presence of polypharmacy or the increase in ACB score represents a more significant increase of falls and harm. In addition, of patients admitted with falls, 29.8% were found to have drug-related orthostatic hypotension, 24.7% had drug-related bradycardia, 37.3% were taking regular centrally acting agents, and 12.0% were taking inappropriate hypoglycemic agents. All these interconnected factors contribute to falls risk and play a crucial role in the progression of the cycle of frailty and has been linked to poorer outcomes for older patients in terms of maintaining independence and mortality.14, 15

Undesirable effects of anticholinergic medications arise from their effect on G-protein coupled muscarinic receptors present in both peripheral and central nervous systems. Peripheral anti-muscarinic effects are usually associated with short term use of anticholinergics. However, many of these medications cross the blood brain barrier and affect the central nervous system directly, and this is more pronounced in older adults where age-related changes in the blood brain barrier disrupt its function.16 By demonstrating the impact of polypharmacy and cumulative ACB in older adults, particularly with respect to falls in this study, we highlight the importance of pharmacological rationalization and deprescribing.

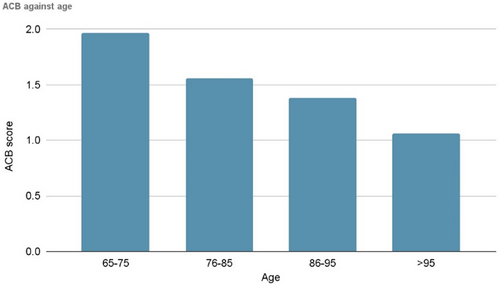

We found a progressive numerical decline in polypharmacy and ACB against age without statistical significance due to numbers (Figure 2). This might be attributed to changes in physiology and drug metabolism with age such that some drugs become obsolete and/or because this population may have greater contact with health care professionals either in primary or secondary care who deprescribes, thus reducing polypharmacy.

Falls are often multifactorial and are both an association and cause of increased frailty. Research into interventions to reduce the risk of falls is ongoing, but even multifaceted interventions have only shown modest benefits.17 Identifying culprit medications and drug classes with a view to develop a structured medication review for those at risk of falling could therefore improve outcomes and relieve pressure on the health care system.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance on falls in older people recommends that people who have had a fall or are at increased risk of falling should have a medication review as part of a multifactorial risk assessment. It is recommended that psychotropic medications which carry a high ACB should be discontinued, if possible, to reduce their risk of falling. Despite it being well proven and understood in the literature that ACB is linked to poorer outcomes for older patients, awareness appears to remain low in clinical environments. A study conducted in 2020 showed that there is a limited understanding of the potential harms of starting regular anticholinergic medications among clinical staff.18 Therefore, the process of due pharmacovigilance remains to be embedded into clinical practice among the wider medical team who care for patients above the age of 65 years.

Our findings clearly validate the importance of rationalizing and balancing risks and benefits of starting medications with any ACB. There are several validated tools that assess the burden of anticholinergic drugs. Although there is heterogeneity in the clinical value of these scales and an absence of an established gold standard, current evidence suggests that the ACB score is of higher quality compared to other tools.19 We therefore suggest the use of the online based ACB calculator (accessible on http://www.acbcalc.com/) in daily clinical activity to reduce potentially inappropriate medications for older patients. An ACB score ≥ 3 confers a heightened risk of cognitive and functional impairment, falls, and mortality. As demonstrated in our study, it is also important to consider lower potential anticholinergic drugs as cumulative effects can lead to high ACB.

Falls and their complications have significant clinical and financial implications for secondary care, with an estimated cost by the National Health System (NHS) of more than £2.3 billion per year.20 Therefore, falls impact quality of life, wellbeing, and health care resources. With appropriate pharmacovigilance, medication rationalization with regular review and education toward reducing the need for initiating medications with ACB, there are potentially enormous cost savings. This ranges from reduced prescription costs, to preventing acute admissions related to falls and their complications and costs associated with managing general frailty. Further study and more thorough cost benefit analysis is awaited to corroborate this.

5 CONCLUSION

There is a high incidence of polypharmacy among older hospitalized adults. Our study clearly demonstrates that polypharmacy and cumulative ACB score are significantly positively associated with increased incidence of falls. Furthermore, the presence of polypharmacy and each unit rise in ACB score have a stronger effect of increasing falls risk when compared to age and comorbidity. ACB and polypharmacy are modifiable risk factors, and our findings strongly support deprescribing, when possible, to prevent falls and improve outcomes in older adults.

6 LIMITATIONS

As a single-center study at a district general hospital, we cannot generalize our results to other settings. Furthermore, our trust is based in southern England, where population demographics and socioeconomic status may differ from those elsewhere.

The classification of patients admitted with or without falls does not take into account the frequency of falls in either group. Additionally, patient's ACB scores were calculated at a single time point (ie, at admission). Although only regular medications on the national database at the time of admission were taken into account when calculating ACB scores, this might not reflect an accurate picture of the cumulative anticholinergic burden of each patient.

We also acknowledge that extracting information from medical notes requires second-hand interpretation and may not be representative of the full clinical picture. The Rockwood Clinical Frailty Score was not included because of the potential inconsistencies in interpretation. We decided to utilize the ACB score instead of other anticholinergic scoring methods as this was the most widely implemented and established scoring system.21

Considerations were made for the utilization of sample size calculations to ensure the study was powered appropriately. Despite achieving significant results in a number of outcomes, we acknowledge the risk of a type 2 error occurring with our experimental sample size. Therefore, we were unable to discount an association among polypharmacy, ACB, and those variables which did not achieve statistical significance with observed effect sizes.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All nine authors contributed to the manuscript. All were involved in the design of the study. Collected and verified the data: Wong, Weaver, Marsh, Mon, and Dapito. Responsible for the data analysis: Wong. Wrote the manuscript: Wong, Weaver, Marsh, Mandal, and Missouris. All authors were involved in the final approval of the manuscript. Wong and Weaver are joint first authors. Mandal and Missouris are acting as guarantors of the submitted work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors understand the policy of declaration of interests. H.L.W., C.W., L.M., K.O.M., J.D., F.R.A., R.C., A.K.J.M., and C.G.M. all declare that that they have no competing interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

As an analysis using clinically collected, non-identifiable data, this work does not fall under the remit of National Health Service Research Ethics Committees. This study was approved by our institution's Research, Quality Improvement and Audit Department with reference FXP-48. This statement is also present in the methods section of our manuscript. It was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Some data may not be made available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.