Beef Cattle Markets and COVID-19

Charles C. Martinez is an Assistant Professor and Extension Economist in the Department of Agricultural Resource and Economics at the University of Tennessee. Joshua G. Maples is an Assistant Professor and Extension Economist in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Mississippi State University. Justin Benavidez is an Assistant Professor and Extension Economist in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Texas A&M University.

Editor in charge: Craig Gundersen

Abstract

Cattle producers and markets faced massive disruptions due to COVID-19 in both supply and demand for cattle and beef. Restaurant and food service shutdowns affected beef demand. Closures and slowdowns of beef processors caused a logjam of live cattle in the supply chain. The resulting effects on cattle producers at all levels were lower prices and abnormal cattle flows, but the magnitudes of those effects were not homogenous across size and type of cattle. In this article, we detail how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected cattle markets and cattle producers across the different sectors. We also discuss policy responses and considerations.

Introduction

The US beef cattle industry faced significant disruptions in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the initial shock of the disruption is in the past, the effects are ongoing as the industry works through both supply and demand responses (CAST 2020). The flow of cattle through the supply chain slowed and altered in response to closures and the incorporation of personal protective equipment (PPE) at cattle processing plants (Dyal et al. 2020; Reuters 2020). Additionally, demand for beef faced a sharp decline in the food service sector and a boom in the grocery store setting (Lusk, Tonsor, and Schulz 2020). The combined effect on cattle producers was a drastic drop in prices. An economic damage report in early April 2020 by Peel et al. (2020) estimated the total effect of COVID-19 on the beef cattle industry to be $13.6 billion and noted “additional impacts are likely in the future.”

The US is a global leader in beef cattle production with more than 80 million beef cattle (USDA, NASS 2020a) and nearly 730,000 farms with beef cows (USDA, NASS 2019). The US has the largest annual beef production, the third largest cattle herd, and the largest fed-cattle industry in the world (FAO 2018). In 2019, US beef cattle generated $66.2 billion in gross income (USDA, NASS 2020d). US cattle production transitions through three distinct stages: cow-calf operations, feedlots, and slaughter/packing facilities. Between the cow-calf and feeding stages are enterprises known as stocker and background operators who purchase and develop calves to be later placed into feedlots. Due to these transitions, cattle often change ownership multiple times prior to processing and cattle flow to and from different geographical locations to match available forage, feedlot capacity, and processing capacity. These intricacies add significant complexity to the beef cattle production system.

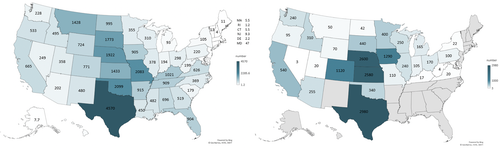

Over time, a geographically distinct supply chain has developed, which has fostered regional specialization for different stages of production, thereby creating an elaborate and cyclical flow of cattle (Anderson, Robb, and Mintert 1996; Anderson, Mintert, and Brester 1998; Asem-Hiablie et al. 2015; Asem-Hiablie et al. 2016; Asem-Hiablie et al. 2017; Asem-Hiablie et al. 2018; Thayer et al. 2019). Currently, the U.S. cattle production system is supported by many cow-calf producers distributed across the country (figure 1), stocker and background operators dispersed across the great plains and a few other areas, a relatively concentrated feedlot industry in the center of the country, and a packing segment with operations owned by a few firms positioned close to feedlots. Most cow-calf operations are small, with an average of 43.5 beef cows, and are dispersed throughout every U.S. state (USDA, NASS 2019). Feedlots are a distinct phase of the supply chain with lots holding 1,000 head or more capacity in Kansas, Nebraska, and Texas, accounting for over 55% of cattle to feed in the U.S. (USDA, NASS 2020b).

The differing structures of operations at separate levels of the supply chain led to differing COVID-19 effects on producers. Structurally, cow-calf operations are the most unique segment of the cattle industry since all other segments are margin operators. Stockers, backgrounders, and feedlot producers regularly purchase cattle throughout the year with the intention of later selling the same animal (or beef). Cow-calf producers invest in depreciable assets (cows) and generate revenue from the offspring of the breeding stock. The cow-calf sector is primarily a fixed-cost operation and producers earn revenue from breeding stock one time per year when the offspring are sold or when cows are culled. There are also different types of price risk management tools available to producers at each level, which further complicate understanding the effect of the sharp market declines.

The following sections of this paper provide an overview of the effects of COVID-19 on each sector of the US cattle the supply chain through the summer of 2020, the risk management options available for each sector, policy responses to the losses induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, and policy considerations.

Cow-Calf Producers

Cow-calf production is the first stage of the cattle production system. Producers in this stage maintain herds of breeding stock and earn revenue by selling offspring of those cows and bulls. The cow-calf sector exhibits the longest production time lags. Once a breeding decision is made, the gestation period for cows is nine months. Even after calves are born, typically another six to nine months will pass prior to those calves being sold. While calves are born in all months of the year, the most common production cycle in the U.S. is breeding in spring, calving the following winter, and selling the calves late in the following summer. These lengthy production lags expose producers to significant price risk.

Cow-calf operations breed and develop the supply base of 400- to 700-pound calves that will eventually be fed in feedlots. These calves are a major source of revenue for producers. There are relatively few price risk management tools available for the cow-calf sector which leads to increased exposure to market fluctuations compared to the other market segments. For example, there are no Farm Bill Title I price safety net programs or futures contracts directly tailored to the cow-calf sector. The cattle weight specifications for the CME Feeder Cattle futures contract are 700- to 899-pound feeder steers, which is larger than most calves sold by cow-calf producers (CME Group 2020a). The Livestock Risk Protection (LRP) insurance product attempts to address some of these issues with weight adjustment factors for lighter cattle, but the structure of the program is more applicable to heavy feeder cattle than the lighter calves usually sold by cow-calf producers.

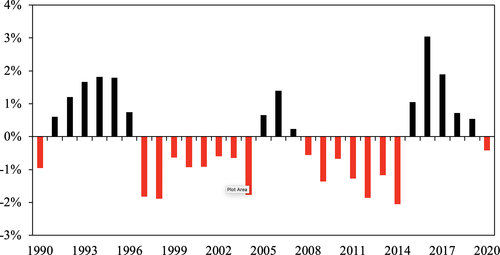

The outlook for returns to cow-calf producers was relatively bright entering 2020. After two years of low prices spurred in part by large supplies, cow-calf producers were hopeful for a better market setting in 2020. After five years of a growing beef cow herd, the January 1, 2020 cattle inventory report showed the first decline in the national herd since 2014 (USDA, NASS 2020a). Figure 2 displays the year-over-year change in January 1 cattle inventory estimates for 1990–2020. This preceding period of growth was spurred by historically high cattle prices in 2014–2015 and the increased inventories were a key driver of lower prices immediately preceding 2020.

The 2020 USDA Livestock Outlook report forecasted average 2020 feeder cattle prices of $146/hundredweight (cwt), an increase from $142.23/cwt in 2019 (USDA 2020). A key driver of this expected price increase was the expected decrease in supply of feeder cattle available due the smaller cow herd. The $146/cwt estimate is a national average. Regional differences or “basis,” which typically accounts for transportation cost, exist creating different local prices nationwide, though nationwide prices movements are typically correlated.

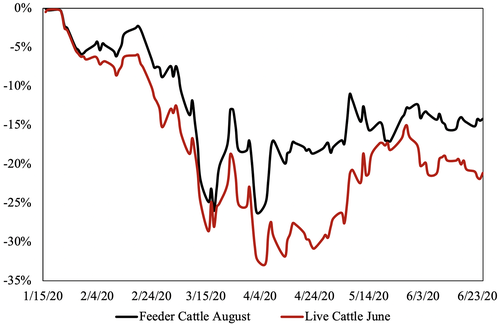

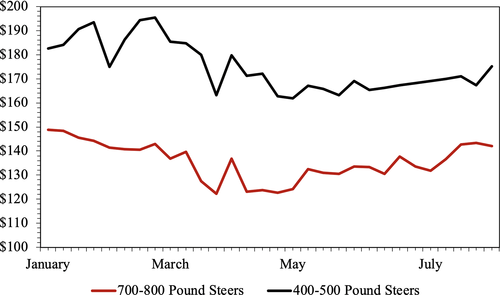

The CME feeder cattle futures are not a direct representation of cow-calf producers since the contract specifications are for larger cattle than are typically sold by cow-calf producers. However, changes in feeder cattle futures prices do generally reflect the current market changes effecting cow-calf producers. As shown in figure 3, the price of the August 2020 CME feeder cattle futures contract declined by more that 25% from the January 15, 2020 price during parts of March and April due to COVID-19. Prices hovered around 15% below January 15 levels during May and June. The direction of price changes in the CME Feeder and Live Cattle Futures Contracts shown in figure 3 were similar to those occurring at local auction markets across the U.S. for calves sold by cow-calf producers. Figure 4 shows the auction market prices for 400- to 500-pound steer calves in the Southern Plains area. The sharp price declines were a direct hit to cow-calf producers selling cattle during these times.

A small consolation for the cow-calf sector through the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic was the price of cull cows (Griffith and Martinez 2020). Dine-in restaurant closures and the onset of recession fears and realities have driven a change in the form of beef products consumed. An increase in the demand for, and as a result the price of, ground beef led to an increase in the demand for cull cows, which contribute more as a percentage of carcass to ground beef than fattened cattle. The price of cull cows rose from approximately $52/cwt the first week in January to over $65/cwt through most of June (USDA, AMS 2020b). The move does follow historic seasonal patterns; however, the percentage change (26% higher) in the value of cull cows over the first six months of 2020 was greater than historic percentage changes (11% higher from 2014–2019). While asset liquidation (selling breeding stock) is not a long-term solution for profitability, it does provide short-term cash flows and the increased prices were a welcome respite from the losses in the cow-calf sector.

Cow-calf producers will continue to feel the effects of COVID-19 throughout 2020 and into 2021. Since cow-calf producers are not margin operators, the value received for calves is effected by downstream losses (i.e. stocker/backgrounding and feedlots). The fixed cost nature of the cow-calf sector means losses in other sectors of the beef cattle industry may eventually accrue to cow-calf producers by way of lower prices over time. Combined with relatively few price risk management alternatives, the cow-calf sector is likely more exposed to prolonged effects than other beef cattle sectors.

Stocker and Backgrounding Producers

The stocker and backgrounding sector of the beef cattle industry can be thought of as a middle agent between the cow-calf producer and the feedlot sector. Stocker and backgrounding producers are margin operators who profit from purchasing light-weight calves from cow-calf operations (or other stocker and backgrounders), feeding for cost-effective weight gains, and reselling them at a later date (or retaining ownership through finished weight or slaughter). Cattle bought by stocker and backgrounders are typically sold or placed into feedlots after the desired weight is achieved, typically between 650–800 pounds (Peel 2006). Due to stocker and background operations relying heavily on high input costs of pastures and/or grain to add weight to the animal, they operate on small margins. The stocker/backgrounding sector is the most difficult to define because it encompasses a wide breadth of operation types and cattle weights. Additionally, it varies by location and time of year depending on the forage or feedstuffs available. There are no directly reported estimates of stocker cattle inventories. Peel et al. (2020) estimated 15.5 million head of stocker cattle as of February 1, 2020.

Stocker and backgrounding producers have better price risk management tools available than the cow-calf sector. CME feeder cattle futures contracts are more appropriate for this sector due to contract specifications more accurately representing the size of cattle leaving typical stocker or backgrounding operations. LRP is also better suited for the larger cattle typically sold from this sector. However, previous work has shown that many producers in the stocker/backgrounder stage do not utilize price risk management tools (Johnson et al. 2010) which likely left a large number of producers exposed to the sharp price declines.

Figure 4 shows the auction market prices for 700–800 pound feeder steers in the Southern Plains area. The most significant damage to the stocker and backgrounding sector occurred to the cattle on hand when the sharp price drop occurred. These cattle would have been purchased at higher prices and faced sharply lower sale prices than were expected. The positive outlook for 2020 not only brought optimism to cow-calf producers who had fall born calves to sell in the spring of 2020, but also for the stocker and background operators who purchased caves in the fall and winter of 2019 to sell in the spring of 2020. For producers who bought cattle in the fall with expectations of favorable spring prices, their expected profit margins were erased with the price declines due to COVID-19.

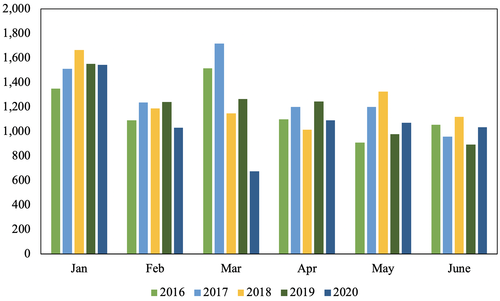

The overall effect of COVID-19 on the stocker and backgrounding sector was defined by more than just the price decline. As both the cash price and futures price began to plummet, the sellers of feeder calves (cow-calf producers, stocker and background operators) were left with two options, sell or hold on and see if prices turn upward. Figure 5 displays the monthly receipts for feeder and stocker cattle for the years 2016–2020. In reaction to the lower prices, feeder calf sales declined as producers held cattle longer than expected and incurred additional feeding costs. Sales of feeder calves in March 2020 were approximately 47% below March 2019 (Martinez and Griffith 2020). Often, retaining calves on pasture was a strategy to wait out the market in hopes of a price rally. As prices began to increase in the cash market, transactions began to increase, which brought April's total number sold back within range of recent years. Additionally, as a direct result of the deferred sales in late spring, the number of head sold in May and June of 2020 were higher than 2019.

Full pens in feedlots, the next stage of production, as a result of limited packer capacity limited the space available for new feeder cattle. The number of cattle placed into feedlots is another indicator of the movement of feeder cattle. Placements of cattle into feedlots in March and April were 22% and 23% lower, respectively, than the same months in 2019. During these two months, 867,000 fewer head of cattle were placed into feedlots than in the same period of 2019. The lower market prices and lack of physical space incentivized stocker and backgrounding producers to continue to add pounds outside of feedlots.

In total, stocker and backgrounding producers kept cattle longer than expected while incurring additional production costs and sold their cattle for less than expected prior to COVID-19. Due to the margin nature of this sector, the effects were felt sharply in the short-run for the cattle in inventory but could be somewhat negated in cattle purchases after the decline by the ability to purchase the next set of cattle at a lower price.

Feedlot Producers

As a result of the beef herd increasing for five consecutive years, there was a large number of cattle in feedlots at the beginning of 2020. Given the long production lags in cattle production where cattle on feed are typically more than a year removed from the cow-calf operation, the recent declines in beef cow numbers have yet to be reflected in lower feedlot inventories. The January 1, 2020 USDA Cattle on Feed (COF) report showed feedlot inventories at just under 12 million head in feedlots with more than 1,000 head capacity (USDA, NASS 2020b). This was the largest January 1 total since 2008, and almost every month through 2019 broke the record for the number of cattle on feed in that month. In the first quarter of 2020, the large numbers of cattle on feed led to approximately 6% higher beef production compared to 2019 (USDA 2020c). Put simply, the feedlot sector entered the COVID-19 pandemic with very large supplies.

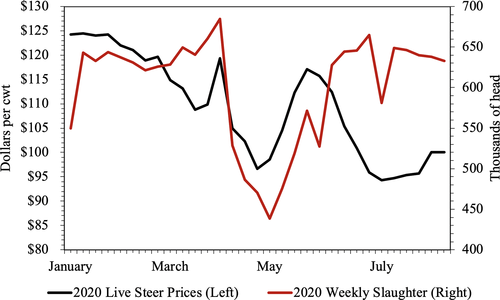

The 2020 USDA Outlook for live cattle (i.e. cattle leaving feedlots to be processed) was $117 per cwt, which was essentially the same as the average price in 2019 (USDA 2020). The large supplies were viewed as a potential headwind to prices, but on the supportive side, the Phase 1 trade agreement with China was being finalized and there was hope for increased beef exports. Live cattle prices rose steadily to close 2019 and there was increased optimism due to prices normally finding a seasonal peak in the spring (figure 6).

The feedlot sector of the beef cattle industry is the last point in the chain prior to cattle being processed for beef. As such, this sector was closest to the COVID-19 shocks on both beef demand and supply. As the state of emergency occurred across the country, numerous businesses including restaurants and schools were forced to close and these closures affected the demand of US beef. Demand for live cattle was also affected and prices declined, rose briefly, then declined again into late spring. The CME live cattle futures specifications match relatively well with the cattle coming out of feedlots and hedging is a commonly used price risk management tool for feedlot producers. This sector is also the most likely to utilize price risk management due in part to the large size of many operations. As such, there were likely many, though certainly not all, feedlot cattle that were protected against the sharp price declines. As cash prices declined, so did the expectation for future live cattle prices as attention shifted toward processing concerns. At multiple points in April, the June live cattle futures contract was more than 30% lower than it was on January 15, 2020 (figure 3).

COVID-19 outbreaks in the labor force at beef processing facilities led to slowdowns and temporary closures of beef plants. This left feedlot producers with limited options for selling cattle and marketings (i.e. live cattle sold from feedlots) plummeted. Cattle slaughter totals dropped sharply (figure 6) throughout April and bottomed out at a weekly total of approximately 438,000 at the start of May (USDA, AMS 2020a; USDA, NASS 2020c). This was 35% lower than the same week in 2019. Cattle slaughter volume increased and recovered but remained below 2019 levels during May and June. In total, approximately 1.2 million fewer head of cattle were processed in April through June 2020 than during the same period in 2019.

Feedlot producers who could sell cattle faced a decision of marketing their cattle at low prices (and replacing with feeder cattle) or holding the cattle even longer with hope of increased prices. Corn prices declined through the spring which offset some of the increased cost of holding cattle longer (USDA, ERS 2020). However, in many cases, beef plant issues meant feedlot producers simply were unable to sell live cattle that were ready to be marketed and were forced to retain the cattle on feed longer than normal. In response, live cattle weights increased. The average steer carcass weight has hovered around 895 pounds since March, which is 20–40 pounds heavier than 2019 levels at the same time. By marketing fewer, but heavier animals, feeders had limited space between the months of February–May, which led to the limited demand and low placement of feeder cattle. While slaughter totals recovered back to 2019 levels near the end of June due in part to increased processing on Saturdays, a backlog of market ready cattle remained in feedlots.

In total, the COVID-19 effect on the feedlot sector was an unprecedented shock at all levels of their operations. The cattle that feedlots could market were sold at relatively low prices. The cattle that feedlots could not market incurred additional production costs and limited the placement of the next set of feeder cattle. Perhaps the only bright spot was for cattle that were hedged prior to the disruption and could be marketed. The difference between the cash price and the live cattle futures prices was wide for a period of time, which created a large positive basis and increased profitability for hedged cattle.

Policy Responses and Conclusions

The drastic declines in cattle prices among all sectors during March and April led to policy responses to assist producers. Details of the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP) were announced in May 2020 by USDA and the program included direct assistance to farmers (CFAP 2020). This was a significant policy response for cattle producers because it marked the first time that direct payments for inventory were made to cattle producers at all levels. Cattle actually sold between January 15 and April 15 were eligible for the highest payments while cattle on hand between April 16 and May 14 were eligible for a lower payment. This program injected much-needed relief to many cattle producers, especially those who had to move cattle during the lowest price periods, though there were questions about the timing of the sales period that received the highest payments.

The widespread disruptions and price differences between retail, wholesale, and farm level prices have also led to additional calls for adjustments to the cattle industry (BEFF 2020). Price discovery and the methods in which live cattle are transacted are active discussions among cattle producers and industry. Similar discussions are also active in other industries such as the pork industry (AEPP Beef and Pork Marketing Margins 2020). Additional risk management tools or increased subsidies for current tools such as LRP are other avenues being explored. Policies targeting relief for the feedlot sector and the backlog of cattle have been proposed. These and any other potential adjustments require careful consideration of unintended consequences for the cattle industry in the long run.

The shutdowns of COVID-19 effected the beef cattle industry dramatically, and some segments felt the market shift sooner than others. The segment that was hit immediately was the beef packing segment. The dramatic shift or decrease in demand from the food industry caused packers to alter their demand for live cattle. The change in demand for live cattle led to a demand change for feeder cattle and that trickled down to the cow-calf producers.

There are lingering questions surrounding the demand for cattle and beef; namely, have preferences changed due to COVID-19? Will at-home consumption remain the norm even upon full reopening? Will willingness to pay for meals prepared outside the home decrease? All of these questions have implications not only for the beef market but for the value of different cattle attributes and the producers raising the cattle.