Assessment of concurrent neoplasms and a paraneoplastic association in MOGAD

Young Nam Kwon and Nanthaya Tisavipat contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Cases of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody-associated disease (MOGAD) co-occurring with neoplasms have been reported. In this international, retrospective cohort study in South Korea and the USA, 16 of 445 (3.6%) patients with MOGAD had concurrent neoplasm within 2 years of MOGAD onset, resulting in a standardized incidence ratio for neoplasm of 3.10 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.77–4.81; P < 0.001) when compared to the age- and country-adjusted incidence of neoplasm in the general population. However, none of the nine tumor tissues obtained demonstrated MOG immunostaining. The slightly increased frequency without immunohistopathological evidence suggest with true paraneoplastic MOGAD is extremely rare.

Introduction

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody-associated disease (MOGAD) has been identified as a distinct autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS.1 Per the 2021 paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome (PNS) diagnostic criteria, MOG-IgG is designated a low-risk antibody,2 and rare cases of MOGAD with concomitant neoplasm have been reported.3, 4 We aimed to investigate the frequency of concurrent neoplasm in MOGAD compared to the expected rate in the general population in large MOGAD cohorts from South Korea and the USA, describe the clinical characteristics, determine MOG expression in neoplastic tissues, and apply the criteria for PNS2 in patients with MOGAD and tumors.

Subjects/Materials and Methods

Study population and data collection

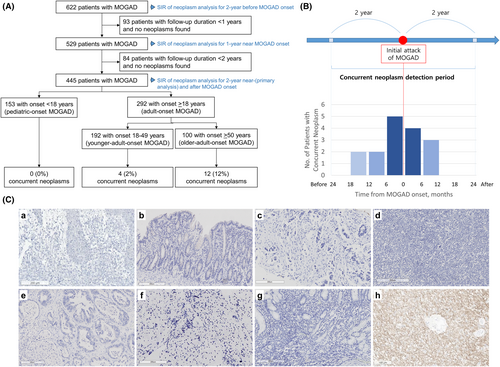

This is an international, multicenter, retrospective cohort study of 622 MOGAD patients from nine hospitals (Data S1) in South Korea (August 2012–April 2023) and Mayo Clinic, USA (January 2000–April 2023) (Fig. 1A). A total of 605 (97.3%) patients fulfilled the 2023 International MOGAD Panel diagnostic criteria.1 MOG-IgG was tested by live cell-based immunofluorescence assay as described previously.1, 5-7 The cutoff points for clear positive MOG-IgG titers were FACS ratio >2.36 using FACSCaliber (BD bioscience)5 or >3.65 using Cytomics FC 500 (Beckman Coulter)1 in South Korea and titer ≥1:100 or binding index ≥10.0 at the Mayo Clinic Neuroimmunology Laboratory.1 According to diagnostic criteria for PNS,2 concurrent neoplasm was defined by diagnosis within 2 years of MOGAD onset (Fig. 1B). Screening and investigation for tumors were performed at the physicians' discretion. Patients included for the primary analysis were followed for at least 2 years or diagnosed with concurrent neoplasm within 2 years of MOGAD onset (Fig. 1A). Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the 2-year pre-MOGAD period, 2-year post-MOGAD, and MOGAD patients with at least 1 year of follow-up.

Identification of patients with concurrent neoplasm was conducted by chart review together with the Mayo Data Explorer tool at Mayo Clinic.8 Data for the South Korea cohort were abstracted from chart review. The following search string “cancer OR carcinoma OR histiocytosis OR leukemia OR lymphoma OR malignancy OR melanoma OR neoplasm OR tumor OR sarcoma OR seminoma OR teratoma OR thymoma” was incorporated into free-text search in the electronic medical records of MOGAD patients through the Mayo Data Explorer.8 After the initial identification of MOGAD patients with neoplasm, chart review was performed for case ascertainment. Squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma of skin were excluded due to their localized nature.

Standardized incidence ratio calculation

MOG immunostaining in neoplasm tissues and PNS-care score

Available neoplasm tissues from MOGAD patients were retrieved for MOG immunostaining. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) 5-μm thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemistry. The primary antibodies anti-MOG (Rabbit clone, 1:1000, Abcam, Ab109746) were applied to the sections and incubated overnight at 4°C after steam antigen retrieval with citric acid buffer (pH 6.0, DAKO). The staining was performed with EnVision™ FLEX immunohistochemistry system (DAKO). Negative control was performed by omitting the primary antibody. Normal human spinal cord (in Mayo Clinic) or glioblastoma brain tissue (in South Korea) were used as a positive control for MOG immunohistochemistry. The PNS-Care score, as defined in the 2021 updated diagnostic criteria,2 is applied to patients with concurrent neoplasms.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics between the South Korea and the Mayo Clinic cohorts were compared by Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables. SIRs with 95% CIs were calculated according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry guidelines.10 Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed alpha level <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 26 for Windows; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent

All patients provided consent for the use of their clinical records and pathology specimens for research purposes through the Mayo Clinic Centre for Multiple Sclerosis and Autoimmune Neurology biorepository, Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH), or Severance Hospital. This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of SNUH (approval number: H-1907-163-1050), Severance Hospital (approval number: 4-2023-1060), and Mayo Clinic (approval number: 20-002897).

Results

A total of 445 MOGAD patients with at least 2 years of follow-up (56.4% female; 49.2% Asian and 47.9% White) were included (Table 1). The median age at MOGAD onset was 28.2 years (interquartile range [IQR], 12.1–48.0), and the median disease duration was 5.4 years (IQR, 3.1–9.1). Sixteen patients (3.6%; 95% CI: 2.2%–5.6%; South Korea, 12; Mayo Clinic, 4) with MOGAD had a concurrent neoplasm, including two previously reported cases,11, 12 all of whom were adults. The diagnosis of neoplasm was made within 1 year before or after MOGAD onset in 14/16 patients (87.5%), and preceded the onset of MOGAD in 9/16 (56.3%) (Fig. 1B).

| Baseline demographics | Total patients (n = 445) | Mayo Clinic (n = 230) | South Korea (n = 215) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 251 (56.4) | 142 (61.7) | 109 (50.7) | 0.022 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 219 (49.2) | 5 (2.2) | 214 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| Black | 8 (1.8) | 8 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.008 |

| White | 213 (47.9) | 212 (92.2) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Others | 5 (1.1) | 5 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.062 |

| Adult-onset MOGAD, n (%) | 292 (65.6) | 152 (66.1) | 140 (65.1) | 0.842 |

| Age at onset, years, median (IQR) | 28.2 (12.1–48.0) | 30.8 (13.1–47.4) | 26.0 (11.4–49.1) | 0.632 |

| Pediatric-onset MOGAD (<18 years), n (%) | 153 (34.4) | 78 (33.9) | 75 (34.9) | 0.842 |

| Adult-onset MOGAD (≥18 years), n (%) | 292 (65.6) | 152 (66.1) | 140 (65.1) | 0.842 |

| Older-adult-onset MOGAD (≥50 years), n (%) | 100 (22.5) | 49 (21.3) | 51 (23.7) | 0.571 |

| Age at last follow-up, years, median (IQR) | 35.5 (20.4–53.9) | 38.0 (23.5–53.9) | 32.8 (18.9–55.1) | 0.136 |

| MOGAD disease duration, years, median (IQR) | 5.4 (3.1–9.1) | 6.0 (3.7–10.2) | 4.7 (2.7–8.3) | <0.001 |

| Neoplasm at any point in life, n (%) | 29 (6.5) | 10 (4.3) | 19 (8.8) | 0.082 |

| Concurrent neoplasm within 2 years of MOGAD onset, n (%) | 16 (3.6) | 4 (1.7) | 12 (5.6) | 0.040 |

| In pediatric-onset MOGAD (< 18 years) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| In adult-onset MOGAD (≥ 18 years) | 16 (5.5) | 4 (2.6) | 12 (8.6) | 0.037 |

| In older-adult onset MOGAD (≥ 50 years) | 12 (12.0) | 3 (6.1) | 9 (17.6) | 0.122 |

| Standardized incidence ratio; (95% CI: p-value) | ||||

| All MOGAD | 3.10 (1.77–4.81, <0.001) | 1.65 (0.43–3.65, 0.227) | 4.40 (2.26–7.23, < 0.001) | – |

| Adult-onset MOGAD | 3.18 (1.82–4.94, <0.001) | 1.69 (0.44–3.76, 0.214) | 4.51 (2.32–7.43, <0.001) | – |

- Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MOGAD, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease; n, number.

In our combined cohort, the SIR was increased at 3.10 (95% CI: 1.77–4.81; P < 0.001). SIR elevation was influenced by the South Korean cohort (SIR, 4.40; 95% CI: 2.26–7.23; P < 0.001), while trended to be high without statistical significance in the Mayo Clinic cohort (SIR, 1.65; 95% CI: 0.43–3.65; P = 0.227) (Table 1). In the sensitivity analyses, both in the 2-year pre-MOGAD (n = 622) and 2-year post-MOGAD (n = 445) periods, the SIRs were increased at 2.74 (95% CI: 1.24–4.82; P = 0.007) and at 2.58 (95% CI: 1.02–4.85; P = 0.021), respectively. Among MOGAD patients with 1 year of follow-up (n = 529), the SIR was also elevated at 4.16 (95% CI: 2.27–6.63; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

| Cohorts | Number of patients | Observed number of patients with concurrent neoplasm, n (%) | Expected number of patients with neoplasm, n | SIR | 95% CIa | p-valuea | Neoplasm incidence rate, per 100 py | Difference in neoplasm incidence rate (observed–expected), per 100 py |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | ||||||||

| All MOGAD | 445 | 16 (3.6) | 5.16 | 3.10 | 1.77–4.81 | <0.001 | 0.90 | +0.61 |

| Adult-onset MOGAD | 292 | 16 (5.5) | 5.03 | 3.18 | 1.82–4.94 | <0.001 | 1.37 | +0.94 |

| Mayo clinic cohort | ||||||||

| All MOGAD | 230 | 4 (1.7) | 2.43 | 1.65 | 0.43–3.65 | 0.227 | 0.43 | +0.17 |

| Adult-onset MOGAD | 152 | 4 (2.6) | 2.36 | 1.69 | 0.44–3.76 | 0.214 | 0.66 | +0.27 |

| South Korea cohort | ||||||||

| All MOGAD | 215 | 12 (5.6) | 2.73 | 4.40 | 2.26–7.23 | <0.001 | 1.40 | +1.08 |

| Adult-onset MOGAD | 140 | 12 (8.6) | 2.66 | 4.51 | 2.32–7.43 | <0.001 | 2.14 | +1.67 |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||||||

| 2 years before MOGAD onset | 622 | 9 (1.4) | 3.29 | 2.74 | 1.24–4.82 | 0.007 | 0.72 | +0.46 |

| 2 years after MOGAD onset | 445 | 7 (1.6) | 2.71 | 2.58 | 1.02–4.85 | 0.021 | 0.79 | +0.48 |

| 1 year before and after MOGAD onset | 529 | 14 (2.6)b | 3.36 | 4.16 | 2.27–6.63 | <0.001 | 1.32 | +1.01 |

- Abbreviations: MOGAD, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody associated disease; py, person-year.

- a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value of the SIR.

- b Only includes patients with neoplasm diagnosis within 1 year of MOGAD onset.

The 16 MOGAD patients with concurrent neoplasm had a variety of tumors (Table 3). The median time between neoplasm diagnosis and MOGAD onset was 2.3 months (IQR: 5.7 before to 5.6 after MOGAD onset). The most common presentation of MOGAD was optic neuritis (6/16; 37.5%), and 15/16 (93.8%) had clear positive serum MOG-IgG, while one (6.3%) had isolated CSF MOG-IgG-positivity. Persistent seropositivity was noted in 6/9 (66.7%) with repeated MOG-IgG testing at a median of 33.5 (IQR: 11.0–70.3) months. None of the tested coexisting neuronal antibodies were positive in all tested patients. Six (37.5%) had relapsing MOGAD and seven (43.8%) received maintenance immunotherapy. After neoplasm treatment, 12 (75.0%) patients were in remission of neoplasm, while 4 (25.0%) had progression of neoplasm (Table S1). Among the 12 patients with neoplasm remission, three (25.0%) experienced a relapse of MOGAD after the remission of the neoplasm; one of these in the setting of immune-checkpoint inhibitor initiation (case #14, Table 3).12 Of the nine neoplasm tissues obtained, none showed MOG immunostaining (Fig. 1C). The PNS-Care scores of 0–3 confirmed that none of our MOGAD patients with concurrent neoplasm had a paraneoplastic etiology (Table 3).

| Case no. | Details of MOGAD | Details of neoplasm | PNS-Care Score (Clinical/Laboratory/Cancer)b | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset/Sex/Race | Duration of follow-up (years) | Initial phenotype | MRI findings | CSF findingsa | Serum MOG-IgG | CSF MOG-IgG | Follow-up Serum MOG-IgG | No. of attacks/Last maintenance treatment | Type/Stage | Tissue MOG expression | Treatment/Outcome | ||

| 1 | 50s/F/Asian | 4.2 | Rt ON | CE at Rt optic nerve | WBC 0, Prot 50, OCB neg, MBP neg | MFIr 4.66c | Negative | MFIr 2.77c | 6/MMF | Breast cancer | NA |

|

0 (0/0/0) |

| 2 (Kwon et al., 2020) | 30s/M/White | 1.6 | Bilateral ON, myelitis | Swelling and CE at bilateral optic nerves, multifocal patchy T2 HSI at T3–T4 and T8-10 spinal cord | WBC 102, Prot 82, OCB pos, and MBP pos | MFIr 5.15c | Not tested | MFIr 2.54c | 2/None | Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma | Negative | CHOP/No recurrence neoplasm | 3 (2/0/1) |

| 3 | 60s/F/Asian | 3.4 | Brainstem/cerebellar deficit | T2 HSI and subtle at Rt midbrain | WBC 40, Prot 59, OCB neg, and MBP neg | MFIr 10.12c | Not tested | No f/u test | 1/None | Chronic myeloid leukemia | NA | Dasatinib, imatinib, and nilotinib/No recurrence neoplasm | 2 (2/0/0) |

| 4 | 60s/F/Asian | 4.2 | Bilateral ON | CE at bilateral optic nerves, a few T2 HSI in bilateral cerebral WM | WBC 1, Prot 69, OCB neg, and MBP neg | MFIr 4.66c | Positive | MFIr 1.39c | 1/MMF | Colon adenocarcinoma/pT1N1aM0 | Negative |

|

0 (0/0/0) |

| 5 | 40s/F/Asian | 0.3 (expired) | ADEM | T2 HSI in corpus callosum and dentate nucleus | WBC 0, Prot 30.2, OCB | Positive (MFIr NA), no f/u test | Not tested | No f/u test | 1/None | Pancreatic cancer | Negative | Tumor resection/Expired | 3 (2/0/1) |

| 6 | 50s/M/Asian | 0.5 (expired) | Lt ON | CE at Lt optic nerve | WBC 1, Prot 21.7 | Positive (MFIr NA), no f/u test | Not tested | No f/u test | 1/None | Intestinal T-cell lymphoma | Negative | Chemotherapy/Expired | 1 (0/0/1) |

| 7 | 70s/M/Asian | 3.6 | Brainstem/cerebellar deficit | T2 HSI at Lt pons and bilateral cerebellum | WBC 0, Prot 74.5 | MFIr 6.76d | Not tested | No f/u test | 1/None | Multiple myeloma | NA | VRD + denosumab/No recurrence neoplasm | 2 (2/0/0) |

| 8 | 50s/M/ Asian |

3.1 | Cerebral cortical encephalitis with seizure | Multifocal T2 HSI at bilateral frontal, Rt temporal lobes and thalamus, swelling of Rt temporo-parietal cortex, and CE along Rt frontal sulci | WBC 17, Prot 24, and OCB pos | MFIr 5.08d | Not tested | No f/u test | 1/Rituximab | Renal cell carcinoma | NA | Nephrectomy/No recurrence neoplasm | 2 (2/0/0) |

| 9 | 50s/M/Asian | 2.4 | Rt ON | CE at Rt optic nerve, a 3.5-cm partly CE ovoid lesion at Lt precentral gyrus | NA | MFIr 5.56d | Not tested | MFIr 3.27d | 1/None | Rectal cancer/Stage 4 | Negative |

|

0 (0/0/0) |

| 10 | 40s/M/Asian | 3.9 | Brainstem/cerebellar deficit | A few T2 HSI at subcortical WM and brainstem | WBC 33, Prot 38.9, and OCB neg | MFIr 4.66d | Not tested | MFIr 1.60d | 1/None | Small cell lung cancer | Negative | CCRT (etoposide and platinum)/No recurrence neoplasm | 3 (2/0/1) |

| 11 | 30s/F/White | 6.9 | Brainstem/cerebellar deficit, myelitis, and Lt ON | T2 HSI and faint CE at subcortical and periventricular WM, bilateral MCP, and Lt ventral medulla, CE at Lt optic nerve, T2 HSI and faint CE at C3-T1 spinal cord | NA | Titer 1:1,000 | Not tested | Titer 1:100 | 4/MMF | Papillary thyroid cancer/Stage 1 | NA |

|

2 (2/0/0) |

| 12 | 50s/F/White | 4.6 | Rt ON | CE at Rt optic nerve | WBC 2, Prot 69, OCB neg, and MBP pos | Titer 1:100 | Not tested | Titer 1:1000 | 3/MMF | Cystic mesothelioma at abdominal wall* | Negative | Tumor resection/No recurrence neoplasm | 0 (0/0/0) |

| 13 | 60s/F/White | 2.9 | Rt ON | CE at right optic nerve | WBC 1, Prot 40, and OCB pos | Titer 1:1000 | Positive | Titer 1:100 | 1/None | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma /Stage 1B | NA |

|

0 (0/0/0) |

| 14 (Syc-Mazurek et al., 2024) | 50s/M/White | 1.4 | Brainstem/cerebellar deficits | T2 HSI at Lt superior colliculus and multiple small lesions at subcortical and periventricular WM with faint CE | WBC 11, Prot 64, and OCB neg | Titer 1:1,000 | Positive | Titer 1:1000 | 7/Tocilizumab | BRAF+ metastatic melanoma/Stage 4 | Negative (lymph node tissue with metastasis) |

|

3 (2/0/1) |

| 15 | 50s/F/Asian | 2.2 | Cerebral monofocal deficits | T2 HSI and CE at Lt frontal lobe | WBC 6, Prot 58, and OCB neg | MFIr 1.65 | Positive, no f/u test | MFIr 1.17 | 3/Rituximab | Breast cancer/pT1aN0M0 | NA |

|

3 (2/0/0) |

| 16 | 60s/F/Asian | 0.4 | Myelitis | T2 HSI at T7-T11 spinal cord without CE | WBC 140, Prot 191, and OCB neg | MFIr 3.66c | Not tested | No f/u test | 1/None | Early gastric cancer type IIb/T1bN2M0 | Negative |

|

3 (2/0/1) |

- Abbreviations: +, positive; ADEM, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CE, contrast enhancement; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; F, female; FOLFIRINOX, folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin; f/u, follow-up; HSI, high signal intensity; IBI, IgG binding index; Lt, left; M, male; MBP, myelin basic protein; MCP, middle cerebellar peduncle; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MOG, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; MOGAD, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease; NA, not available; OCB, oligoclonal band; ON, optic neuritis; PNS, paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome; Prot, protein; Rt, right; TCHP, docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab; VRD, velcade, revlimid, and dexamethasone; WBC, white blood cell; WM, white matter; XELOX, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin.

- a White blood cells are displayed as /μL and protein as mg/dL.

- b Encephalitis and isolated myelopathy (including myelitis) were categorized as intermediate-risk phenotypes in the PNS criteria. MOGAD presentations with ADEM, cerebral monofocal or polyfocal deficits, brainstem or cerebellar deficits, and cerebral cortical encephalitis were considered variations of encephalitis, and thus were given a clinical score of 2. Patients with a concurrent tumor other than teratoma and had follow-up duration <2 years were assigned a cancer score of 1.

- c Using FACSCaliber (BD bioscience); positive MOG-IgG titers were MFI ratio >2.36.

- d Using Cytomics FC 500 (Beckman Coulter); positive MOG-IgG titers were MFI ratio >3.65.

Discussion

In this large international cohort, concurrent neoplasm was identified in 3.6% of MOGAD patients within 2 years of MOGAD onset, but none demonstrated tumor MOG expression making any paraneoplastic association uncertain. This suggests that universal tumor screening is unnecessary in all new-onset MOGAD patients. However, age-appropriate screening and clinically guided investigations for neoplasm in patients with MOGAD should be pursued. Moreover, symptoms suggesting MOGAD should not be ignored in cancer patients. The strengths of this study include the novel comparison to the background cancer rate using SIR, the large cohort of MOGAD patients assessed in two separate world regions, and the relatively large number of tumors tested for MOG expression (Table 4).20

| Authors (year) | Neoplasm | Initial MOGAD phenotype | Serum MOG-IgG titer | CSF MOG-IgG titer | Follow-up serum MOG-IgG titer | Clinical course of MOGAD | Tissue MOG expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cherian et al. (2022)13 | Breast carcinoma | Myelitis | Strong at 1:10 (titration not done) | NA | NA | Monophasic | NA |

| Cirkel et al. (2021)14 | Ovarian teratoma | Encephalomyeloradiculitis | 1:80 (serum GFAP and ITPR-1 IgGs negative) | 1:2 (concomitant GFAP IgG positive 1:10) | Negative (CSF negative; subsequent CSF ITPR-1 IgG positive 1:100) | Monophasic | Negative |

| Cobo-Calvo et al. (2017)15 | Ovarian teratoma | ADEM | 1:640 | NA | NA | Monophasic | NA |

| Hurtubise et al. (2023)16 | Thymic hyperplasia | ON | 1:80 | NA | 1:80 | Relapsing | NA |

| Jarius et al. (2016)17 | Ovarian teratoma | Brainstem/cerebellar deficits, myelitis | 1: 10,240 | 1:64 | 1:640 (CSF negative) | Monophasic | NA |

| Li et al. (2020)18 | Lung adenocarcinoma (EGFR mutation) | Myelitis, ON, brainstem/cerebellar deficits | 1:10 | 1:100 | (CSF 1:10, 1:32) | Monophasic | NA |

| Rodenbeck et al. (2021)19 | Lung carcinoma (poorly differentiated) | ADEM | 1:160 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Trentinaglia et al. (2023)20 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Brainstem/cerebellar deficits | 1:320 | NA | NA | Relapsing | NA |

| Trentinaglia et al. (2023)20 | Melanoma | Cerebral mono/polyfocal deficits | 1:320 | NA | 1:160 | Monophasic | NA |

| Wildemann et al. (2021)3 | Ovarian teratoma | ON | 1:320 | Negative | 1:32 | Relapsing | Positive |

| Zhang et al. (2022)4 | Ovarian teratoma | ADEM | 1:10 (after 5 days of IVMP) | NA | NA | Monophasic | Positive |

- Note: Literature review of case reports of MOGAD with neoplasm within 2 years of MOGAD onset from literature through August 2023. The cases from Kwon et al.'s11 and Syc-Mazurek et al.'s21 reports were included in our study (Table 3, Cases #2 and #14) and thus are not shown in this table.

- Abbreviations: ADEM, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; ITPR-1, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1; IVMP, intravenous methylprednisolone; MOG, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; NA, not available; ON, optic neuritis.

Our results suggest a small association between neoplasm and MOGAD, consistent with its categorization as a lower risk antibody in the PNS criteria.2 We found that 14/16 MOGAD patients developed neoplasm within 1 year of MOGAD onset, with even higher SIR than at 2 years, although none demonstrated tumor MOG immunostaining. Notably, two prior MOGAD patients with concurrent teratoma had MOG immunostaining in the tumor suggesting that paraneoplastic MOGAD may occasionally occur.3, 4 Although there was no teratoma in our study, it is noteworthy that MOG staining was attempted on a variety of tumor tissues, including small cell lung cancer, which is high risk for paraneoplastic syndrome, and all results were negative. We hypothesize that in the setting of cancer, dysregulated self-immunity against tumor cells might have contributed to MOGAD attacks manifesting concurrently with neoplasm in our study,22 rather than direct autoantigen presentation by neoplastic tissues as occurs in PNSs.23 Detection bias from increased surveillance in those with MOGAD was another possibility, but the SIR was elevated even in the 2 years before MOGAD diagnosis. Other factors that could have played a role included different methodologies for tumor assessment in our MOGAD cohort than in the reference national databases. There may also be regional differences in frequency of concurrent tumors as South Korea (5.6%) had a higher rate than the USA (1.7%) and a previous Italian cohort (1%).20 This may reflect differences between predominantly Asian and White populations or high hospital accessibility in South Korea where 97% of the population have coverage for regular cancer screening with national health insurance.24 Our findings differ from paraneoplastic AQP4 + NMOSD in which AQP4 expression in tumor tissue is more frequently reported.25

Immunotherapy for MOGAD could potentially influence the incidence of neoplasms and contribute to differences between the groups. However, among the seven cases where neoplasms were identified after the onset of MOGAD, only three patients had received immunotherapy, and the incidence rates were similar between the two cohorts (4/215 [1.9%] in Korea vs. 3/230 [1.3%] at Mayo). Additionally, systemic autoimmune diseases could also affect the incidence of neoplasms, but in our study, none of the MOGAD patients with concurrent neoplasms had coexisting autoimmune diseases. Therefore, the impact of immunotherapy or coexisting autoimmune diseases on our study results is minimal.

Limitations of our study were related to the retrospective design and include potential underreporting of neoplasm and heterogeneity in cancer screening between patients and across different sites. However, our median follow-up duration of 5.4 years should allow for enough time for cancer to manifest. Moreover, MOG immunostaining was not available in all tumor tissues but only in 9/16 (56%).

In conclusion, concurrent neoplasms were found at a higher frequency than the general population within 2 years of MOGAD onset, but all available tumor tissues were negative for MOG immunostaining suggests that paraneoplastic MOGAD is very rare. Nevertheless, investigation for cancer in MOGAD patients with suggestive features should be considered.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to Sung Hyuk Heo, Hye Jung Lee, and Moonhang Kim for their contributions in the collection of clinical and pathological data. This study was supported by funding from an RO1 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS113828) and by the National Research Foundation of Korea (2020R1C1C1012255). External tissues evaluated at Mayo Clinic were obtained through supports from the Center for MS and Autoimmune Neurology (CMSAN) Biorepository. Some of the biospecimens for this study were provided by the Seoul National University Hospital Human Biobank, a member of the Korea Biobank Network, which is supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. All samples derived from the National Biobank of Korea were obtained with informed consent under institutional review board-approved protocols.

Author Contributions

YNK, NT, EPF, and S-MK contributed to the conception and design of the study, and drafting and revising of the manuscript. YNK, NT, YG, SS-M, JYH, J-SK, KC, SO, S-JC, ES, JO, SWK, HYS, BCL, BJK, KSP, J-JS, SHK, S-HP, SJP, JJC, EPF, and S-MK contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. YNK and NT contributed to the statistical analysis, YG, SS-M, HYS, BCL, KSP, J-JS, S-HP, AZ, CFL, SJP, JJC, EPF, and S-MK contributed to revise the manuscript for intellectual content. YNK, NT, SHK, S-HP, AZ, SJP, JJC, EPF, and S-MK contributed to the interpretation of data; EPF and S-MK contributed to the study supervision.

Conflict of interest

YNK received a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea, Eisai, and Korean Neurological Association; lectured, consulted, and received honoraria from Celltrion, Eisai, GC Pharma, Merck Serono, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and CorestemChemon. JJC is a consultant for UCB and Horizon. EPF has served on advisory boards for Alexion, Genentech, Horizon Therapeutics, and UCB. He has received research support from UCB. He received royalties from UpToDate. EPF is a site principal investigator in a randomized clinical trial of Rozanolixizumab for relapsing myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease run by UCB. EPF is a site principal investigator and a member of the steering committee for a clinical trial of satralizumab for relapsing myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease run by Roche/Genentech. EPF has received funding from the NIH (R01NS113828). EPF is a member of the medical advisory board of the MOG project. EPF is an editorial board member of Neurology, Neuroimmunology and Neuroinflammation, and the Journal of the Neurological Sciences and Neuroimmunology Reports. A patent has been submitted on DACH1-IgG as a biomarker of paraneoplastic autoimmunity. SMK has lectured, consulted, and received honoraria from Bayer Schering Pharma, Genzyme, Merck Serono, and UCB; received a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea and the Korea Health Industry Development Institute Research; is an Associate Editor of the Journal of Clinical Neurology. SMK and Seoul National University Hospital has transferred the technology of flow cytometric AQP4-IgG and MOG-IgG assay to EONE Laboratory, Korea.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.