3.1 In situ versus ex situ

3.1.1 Possible pivots

The ability to move is a standard textbook example of a constituency diagnostic. Thus, if RNR involves movement of the pivot, we expect the pivot to be a constituent. Admittedly, the usefulness of this diagnostic is complicated by the fact that not all constituents can move, for a myriad of independent reasons. However, it is still reasonable to expect the range of possible pivots to correspond to the range of moveable constituents.

Even though many accounts of RNR focus on cases in which the pivot is a noun phrase (and the examples we have seen so far all involved noun phrases), other pivots are certainly possible (as discussed by e.g. Bresnan 1974; Postal 1974; 1998; Hudson 1976; Gazdar 1981).

| (12) |

a. |

Jack may be ____, and Tony certainly is ____, [DPa werewolf]. |

|

b. |

Tom said he would ____, and Pete actually did ____, [VPeat a raw eggplant]. |

|

c. |

Terry used to be ____, and George still is ____, [AdjPvery suspicious]. |

|

d. |

Harry has claimed ____, but I certainly don't believe ____, [CPthat Melvin is a Communist]. |

|

|

(Postal 1974, 126–127) |

|

e. |

I can tell you when ____, but I can't tell you why ____, [TPhe left me]. |

|

|

(Bresnan 1974, 618) |

The next question is whether pivots have to be constituents. Postal (1974) assumes that RNR always targets constituents and uses RNR as a constituency test to argue for the raising to object analysis of ECM examples like (13). If the embedded subject does not move to the matrix object position, he reasons, the pivot remains a constituent and the ungrammaticality of (13) is unaccounted for.13

| (13) |

*I find it easy to believe ____, but Joan finds it hard to believe ____, Tom to be dishonest. |

|

(Postal 1974, 128) |

There are two other types of considerations showing that the constituency requirement on RNR is too strong. The examples in (14a)–(14d), due to Abbott (1976), show that the pivot can be larger than a single constituent (and involve multiple constituents), whereas the ones in (15a)–(15c) show that it can be smaller than a single constituent (and involve sub-constituents, so to speak).14

| (14) |

a. |

Smith loaned ____, and his widow later donated ____, a valuable collection of manuscripts to the library. |

|

b. |

I borrowed ____, and my sisters stole ____, large sums of money from the Chase Manhattan Bank. |

|

c. |

Leslie played ____, and Mary sang ____, some country‑and‑western songs at George's party. |

|

d. |

Mary baked ____, and George frosted ____, 20 cakes in less than an hour. |

|

|

(Abbott 1976, 639) |

| (15) |

a. |

Your theory over ____, and mine under ____, generates. |

|

|

(Booij 1985, ex.1b, also discussed in Hartmann 2000, 57) |

|

German |

|

b. |

Philip |

|

sate |

Frühlings ____ und Herbstblumen. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philip |

|

sowed |

spring and autumn.flowers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

‘Philip sowed springtime and autumn flowers.’ |

|

|

(Féry and Hartmann 2005, 73) |

|

Polish |

|

c. |

Jan |

prze ____, |

a |

Piotr |

pod ______, |

pisał |

list do |

prezydenta. |

|

|

Jan |

through |

and |

Peter |

under |

wrote |

letter to |

president |

|

|

‘Jan copied and Peter signed the letter to the president.’ |

There are also many other factors besides constituency, such as focus structure or prosodic weight, that play a role in determining what kinds of elements can be pivots in RNR constructions, as shown by the following contrast from Bresnan (1974).15

| (16) |

a. |

*He tried to persuade ____, but he couldn't convince ____, them. |

|

b. |

He tried to persuade ____, but he couldn't convince ____, the students that he liked. |

|

|

(Bresnan 1974, 615) |

The next set of diagnostics that can help us decide whether the pivot remains in situ or moves out has to do with constraints on movement. If only certain types of phrases can move, we would expect only these types of phrases to be pivots in RNR. This prediction is also not borne out. The following contrast shows that CPs can move but TPs cannot (see Abels 2003). However, TPs are possible pivots in an RNR construction, which is problematic for a movement account (see Bošković 2002; Abels 2003).

| (17) |

a. |

[CP That the earth is not flat]i, everyone knows ti. |

|

b. |

*[TP The earth is not flat]i, everyone knows that ti. |

|

c. |

Everyone knows that ____, and nobody questions if ____, [TPthe earth is not flat]. |

This is not the only case of pivots that are not moveable. In (18a)–(18c), as noted by Johnson (2007), we see that NPs can be pivots in RNR, but cannot undergo either leftward or rightward movement:

| (18) |

a. |

I know Sally's ____, but not Mary's____, parents. |

|

b. |

*Parentsi, I know Sally's ti. |

|

c. |

*I met Sally's ti yesterday parentsi. |

|

|

(Johnson 2007, 16) |

3.1.2 Islands

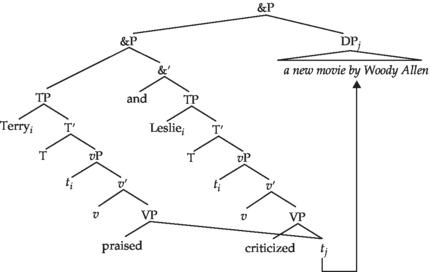

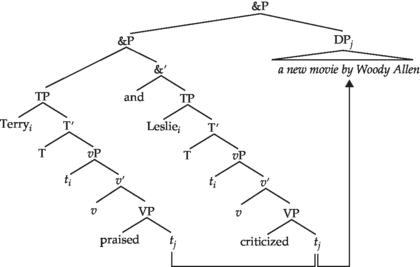

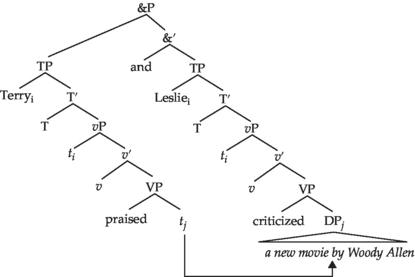

The behavior of RNR with respect to islands is well documented in the literature, going back at least to Wexler and Culicover (1980), who note a difference between movement and RNR constructions with respect to a number of islands. The contrast in grammaticality between the (a) and (b) examples in (19)–(21) provides an illustration. The (a) examples, involving run-of-the-mill wh-movement, are all ungrammatical, whereas the corresponding (b) examples, involving RNR, are fully grammatical.

| (19) |

a. |

*Whati did Leslie ask [wh‑island when John saw ti]? |

|

b. |

Leslie asked [wh‑island when John saw ti] and Terry asked [wh‑island when Bill reviewed ti] a new movie by Woody Alleni. |

| (20) |

a. |

*Whati does Leslie know [complex np‑island the person who wrote ti]? |

|

b. |

Leslie knows [complex np‑island the person who saw ti] and Terry knows [complex np‑island the person who reviewed ti] a new movie by Woody Alleni. |

| (21) |

a. |

*Whati did Leslie leave [adjunct island after seeing ti]? |

|

b. |

Leslie left [adjunct island after seeing ti] and Sue arrived [adjunct island before reviewing ti] a new movie by Woody Alleni. |

This is not to say that RNR is not sensitive to any island violations. The ungrammaticality of (22b) indicates that RNR is subject to the Left Branch Condition. However, its ungrammaticality could also be due to independent properties of RNR, such as the requirement that the pivot occupy (or originate from) the rightmost position inside the two conjuncts. This restriction, referred to in the literature as the Right Edge Restriction, will be the focus of section 3.1.7.

| (22) |

a. |

*Whichi has Mary read ti articles on RNR? |

|

b. |

*Mary read ti articles on RNR and Bill reviewed ti books on ellipsis, recenti. |

The fact that in languages that do allow left branch extraction (such as the Slavic languages, as known since Ross 1967), the equivalent of (22b) is still ungrammatical (as shown in (23b) for Polish), also suggests that movement is not the culprit.

| (23) |

Polish |

|

a. |

Którei Maria przeczytała ti |

artykuły |

o |

RNR? |

|

|

|

|

which Maria read |

articles |

about |

RNR |

|

|

|

|

‘Which articles about RNR has Maria read?’ |

|

b. |

*Maria |

przeczytała____ |

artykuły o |

|

RNR |

a |

|

|

Maria |

read |

articles about |

|

RNR |

and |

|

|

Piotr zrecenzjonował____ artykuły o elipsie, ostatnie. |

|

|

Peter reviewed articles about ellipsis recent. |

|

|

‘Mary read recent articles on RNR and Peter reviewed recent books on ellipsis.’ |

The ungrammaticality of (24b) could be seen as evidence that RNR obeys the Subject Condition. However, this example also violates the so-called Right Roof Constraint of Ross (1967), which requires rightward movements to be clause-bound.16

| (24) |

a. |

*What does [sbj island that John read ti] bother Mary? |

|

b. |

*[sbj island That John read ____, and Bill reviewed ____,] bothered Mary an article on Right Node Raising. |

Given that RNR typically involves coordination, an obvious constraint to consider is the Coordinate Structure Constraint. The general consensus appears to be that RNR does obey the Coordinate Structure Constraint (see e.g. Wexler and Culicover 1980; McCawley 1982; Postal 1998; Johnson 2007; Sabbagh 2007).

There are two parts to CSC; one prevents movement of an entire conjunct, and the other prevents movement of any element contained within one conjunct. The following examples, due to Postal (1998), show that both are operative in RNR.17

| (25) |

a. |

*Tom is writing an article on Aristotle and ____, and Elaine has just published a monograph on Mesmer and ____, Freud. |

|

b. |

* Tom may have bought sketches of Gail and photos of ____, and Bob saw ____, Louise. |

|

|

(Postal 1998, 122) |

The fact that ungrammatical examples become grammatical when movement takes place in an ATB fashion from both conjuncts simultaneously further supports the conclusion that RNR obeys the CSC:

| (26) |

a. |

* Terry watched ____, Leslie ignored the preview, and Bill reviewed ____, a new movie by Woody Allen. |

|

b. |

Terry watched ____, Leslie ignored ____, and Bill reviewed ____, a new movie by Woody Allen. |

If RNR is rightward movement, we might also wonder whether it obeys constraints on rightward movement, if such exist. One discussed by Barros and Vicente (2010) involves the so-called Right Roof Constraint of Ross (1967), which requires rightward movement to be clause-bound, as shown by the contrast between (27a) and (27b). The further contrast between (27b) and (27c) shows that RNR does not have to be similarly clause-bound.

| (27) |

a. |

Alice saw ti, yesterday, [the new headmaster]i. |

|

b. |

*Alice said [that Beatrix loves ti] yesterday, [the new headmaster]i. |

|

c. |

Alice claimed [that Beatrix loves ti], and Claire proved [that Diana hates ti], [the new headmaster]i. |

|

|

(Barros and Vicente 2010, 9) |

A more general issue I would like to conclude this section with concerns cross-linguistic variation. If there are languages in which RNR does obey island constraints, it may well be the case that RNR in such languages does involve movement. This is the argument Sabbagh (2008) makes for Tagalog, showing that in this language RNR is subject to the so-called subject extraction restriction, one of the hallmarks of Austronesian syntax.18

Furthermore, if RNR involves rightward ATB movement, we would expect to find the same cross-linguistic variation with respect to RNR as we find with respect to ATB movement. To illustrate with one example, in a multiple wh-fronting language like Polish, multiple ATB movement is possible as long as both wh-phrases are extracted from both conjuncts simultaneously:

| (28) |

Coj |

komui |

Tomasz |

obiecał |

ti tj |

a |

Ewa |

kupiła |

ti tj? |

|

who.acc |

who.dat |

Tom |

promised |

|

and |

Eve |

bought |

|

|

‘What did Tomasz promise to whom and Ewa bought for whom?’ |

Multiple RNR is also possible:

| (29) |

Tomasz |

obiecał ____ ____, |

a |

Ewa |

kupiła ____ ____, |

nowy |

|

Tomasz |

promised |

and |

Ewa |

bought |

new.acc |

|

computer |

Jankowi. |

|

computer.acc |

Jan.dat |

|

‘Tomasz promised and Ewa bought new computer for Jan.’ |

This seems to support the movement account; however, we have seen similar examples in English (see the discussion in endnote 13), whose grammaticality casts doubt on the correlation between multiple fronting and the availability of multiple pivots in RNR.

Another set of potential arguments bearing on the choice between in-situ and ex-situ accounts comes from the interaction of RNR with VP ellipsis. McCawley (1982) points out that in VP ellipsis contexts, the VP ellipsis site includes the pivot. This is only possible if the pivot does not move.19

| (30) |

a. |

Tom talked ____, and is sure that everyone else talked ____, about politics, but of course you and I didn't [VP Ø]. |

|

b. |

VP = talk about politics |

|

c. |

VP ≠ talk |

|

|

(adapted from McCawley 1982, 100) |

A related argument comes from Abels’ (2004) discussion of the interaction between VP ellipsis and RNR in cases like (31). If the pivot moves, it is not clear why its movement cannot feed VP ellipsis in this case.

| (31) |

*Jane talked about ____, and/but Frank didn't ____, the achievements of the syntax students. |

|

(Abels 2004, 52) |

Perhaps the most forceful recent case for a movement account of RNR comes from Postal's (1998) book. Postal treats RNR as a type of extraction (L-extraction in his terms) and argues that RNR involves the same type of extraction as ATB movement. Even though Postal frames his discussion of RNR as a response to McCawley's (1982) multidominant account of RNR, his arguments also apply to other types of multidominant accounts. Postal points out that with respect to quite a number of constraints, RNR behaves similarly to other constructions involving movement. Among the constraints he considers are: the Coordinate Structure Constraint (which we discussed in this chapter), the Indirect Object Constraint (a constraint that prohibits A-bar movement of the indirect object in a double object construction, illustrated in (32a)), the Genitive Constraint (a constraint prohibiting movement of postnominal of genitives, illustrated in (32b)), the Reflexive Constraint (a constraint preventing so-called inherent reflexives from being extracted, illustrated in (32c)), and a constraint against extraction from exceptive phrases (illustrated in (32d)).20

| (32) |

a. |

*I first offered ____ apples, and then sold ____ peaches, the immigrant from Paraguay. |

|

b. |

*Glen was looking for nieces of ____, but only found cousins of ____, Ted and Alice's. |

|

c. |

*Lois may have perjured/exerted ____, and should have perjured/exerted ____, herself. |

|

d. |

*The nurse wanted to watch everything except ____, and did watch everything except ____, the most difficult and lengthy operation of the day. |

|

|

(Postal 1998: 123–129) |

(33a)–(33d) provide parallel ATB movement examples.

| (33) |

a. |

*Which immigranti did you offer ti apples and then sell ti peaches? |

|

b. |

*Of Ted and Alice'si, Glen was looking for nieces ti but only found cousins ti. |

|

c. |

*Herselfi, Lois may have perjured ti and exerted ti. |

|

d. |

*Which operationi did the nurse want to watch everything except ti and participate in everything except ti? |

The behavior of RNR pivots with allege-class verbs and parasitic gap licensing, Postal (1998) argues, also points toward a movement analysis. The fact that (34a) is grammatical (and parallels (34b), in which the object of allege undergoes movement, rather than (34c), in which it does not) suggests movement.

| (34) |

a. |

They may have alleged to be pimps ____, and probably did allege to be pimps ____, all of the Parisians who the CIA hired in Nice. |

|

|

(Postal 1998, 131) |

|

b. |

Who may they have alleged t to be pimps and probably did allege t to be pimps? |

|

c. |

*They may have alleged them to be pimps. |

So does the fact that RNR can license parasitic gaps, a property associated with overt movement:

| (35) |

Greg decided to buy ____ after reading about pg, and Gail agreed to lease ____ before test driving pg, that new model electric car which actually doesn't work. |

|

(adapted from Postal 1998, 133) |

However, in this case RNR appears to be fed by Heavy NP Shift within each conjunct, so the grammaticality of this example is also compatible with the Heavy NP Shift (rather than RNR of the pivot) licensing the parasitic gap inside each conjunct.

3.1.3 Stranding

The next set of arguments that bears on the ex-situ versus in-situ status of the pivot comes from various types of stranding phenomena. In this section, we will look at two types of stranding: preposition stranding and complementizer stranding. One of the classic arguments against a movement analysis comes from McCloskey's (1986) observation that RNR can strand prepositions in languages in which P-stranding is generally disallowed. His evidence comes from Irish, which disallows P-stranding in movement, including rightward movement, but allows it in RNR. This is shown by the contrast between the grammatical RNR in (36a) and the ungrammatical Heavy NP Shift in (36b).

| (36) |

a. |

Brian |

Mag Uidhir … ag glacadh |

le |

agus |

ag cabhrú |

le |

plandáil |

|

|

|

|

a dtailte féin. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brian |

Magquire take.prog |

with |

and |

help.prog |

with |

planting |

|

|

|

|

their |

lands refl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

‘Brian Maguire … accepting, and helping with, the planting of their own lands.’ |

|

b. |

*Bhi |

me |

ag eisteacht le |

|

inne |

clar |

mor |

fada |

ar an raidio |

|

|

faoin |

toghachan. |

|

|

was |

I |

listen.prog |

with |

yesterday |

program |

great |

long |

on radio |

|

|

about‑ |

the |

election |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

‘I was listening yesterday to a great long program on the radio about the election.’ |

|

|

(McCloskey 1986, 184–185) |

English also provides a relevant, albeit slightly different, contrast. Even though English is generally a language that allows P-stranding, it disallows it in cases of rightward movement, as noted by Ross (1967) and illustrated in (37a). The fact that English RNR allows P-stranding (discussed by Bošković 2004/1996) thus suggests that it is not (rightward) movement.21

| (37) |

a. |

*John talked about ti yesterday [the man you met in Paris]i. |

|

b. |

John talked about ____, and Mary ignored ____, the man you met in Paris. |

|

c. |

Mary ignored ____, and John talked about ____, the man you met in Paris. |

|

|

(Bošković 2004/1996, 19) |

Complementizers also cannot be stranded by movement but can be ‘stranded’ by RNR, which suggests that the pivot remains in situ (see also the discussion of examples (12e) and (17c)):

| (38) |

a. |

*[TP Anything would happen]i, nobody thought that ti. |

|

(Abels 2003, 10) |

|

b. |

Nobody expected that ____, but everyone wondered if ____ [TPJohn would run for president]. |

3.1.4 Binding

The next set of data that bears on the ex-situ versus in-situ debate comes from binding effects. If the pivot undergoes ATB rightward movement, it should c-command the material inside the two conjuncts. And, conversely, if it does not move, it should remain c-commanded by higher elements inside the two conjuncts. Levine (1985) notes that with respect to binding effects, the pivot behaves as if it were in situ. The examples in (39a)–(39c) provide an illustration.

| (39) |

a. |

Terryi liked ____, and Lesliej disliked ____, a picture of herselfi/j on the wall. |

|

b. |

*Terryi liked ____, and Lesliej disliked ____, a picture of herj on the wall. |

|

c. |

*Hei liked ____, but Lesliej disliked ____, a picture of Terryi on the wall. |

Sabbagh (2007), however, points out that this argument is weakened given the possibility of reconstruction. If reconstruction is responsible for the binding effects in wh-questions in (40a)–(40b), it is not clear why the same mechanism (syntactic reconstruction) could not apply to RNR.

| (40) |

a. |

Which picture of herselfi on the wall did Lesliei dislike? |

|

b. |

*Which picture of Terryi on the wall did hei dislike? |

However, as noted by Phillips (1996, 53), reconstruction is not going to explain the NPI-licensing data below. The ungrammaticality of (41a) shows that NPIs generally cannot be licensed under reconstruction. Parallel RNR examples, pointed out by Kayne (1994), are grammatical, which argues against a movement and reconstruction analysis.

| (41) |

a. |

*Which picture of anyone did Leslie not like? |

|

b. |

Mary bought ____, but John didn't buy ____, any books about linguistics. |

|

(Kayne 1994, 146, crediting Paul Portman) |

Variable binding also shows that the pivot (containing a bound pronoun) can be interpreted inside the two conjuncts:

| (42) |

Everyonei suspected ____, but nobodyi really believed ____, that hei was being investigated by the FBI. |

|

(Phillips 1996, 53) |

3.1.5 Scope

So far, most of the arguments we have seen point toward the in-situ analysis of RNR. However, quantifier scope seems to point in the opposite direction. Sabbagh (2007) points out that the quantified pivot can have scope above the conjunction level, as shown in (43a). This cannot be the result of covert ATB movement, given the unavailability of this interpretation in (43b).

| (43) |

a. |

Some nurse gave a flu shot to ____, and administered a blood test for ____, every patient who was admitted last night. someone > every; every > someone |

|

b. |

Some nurse gave a flu shot to every patient, and administered a blood test for every patient. someone > every; *every > someone |

|

|

(Sabbagh 2007, 365) |

Interestingly, such wide scope is also possible when the quantified pivot is embedded inside an island, which suggests that movement cannot be responsible for the wide scope of the pivot in this case.22

| (44) |

John knows [someone who speaks ____], and Bill knows [someone who wants to learn ____], every Germanic language. someone > every; every > someone |

|

(Sabbagh 2007, 367) |

Bachrach and Katzir (2007; 2009), however, show that there is a way to understand wide scope in a non-movement account. To do so, they employ the concept of Delayed Spell-Out alluded to in section 2.2, and argue that the multiply dominated element is not transferred to the interfaces till it is fully dominated. This captures the seemingly paradoxical behavior of the pivot; it does not move, but it can nevertheless scope high.

3.1.6 Relational modifiers

This section discusses the interpretation of RNR examples with modifiers like similar, same, or different. What is interesting about these modifiers is that, on one reading, they require semantic plurality.23 Consider the interpretation of different or the same in (45). On one reading, the so-called external reading (which will be mostly irrelevant for our purposes), it means that John and Bill whistled tunes that were different from some other contextually specified set of tunes. On the other reading, the so-called internal reading, it means that the tunes John whistled were different from the tunes Bill whistled. This is the reading we will be concerned with here.

| (45) |

John and Bill whistled different/the same tunes. |

With a semantically singular subject, the internal reading disappears. (46) can only mean that the tunes John whistled are different from (or the same as) some other contextually defined tunes.

| (46) |

John whistled different/the same tunes. |

What is relevant for our purposes is Jackendoff's (1977) well-known observation that such relational modifiers with internal readings are allowed in RNR constructions:

| (47) |

a. |

John avoided ____, and Bill ignored ____, similar issues/the same man/men with the same birthday. |

|

b. |

John whistled ____ and Mary hummed ____ the same tune/at equal volumes/together. |

|

|

(Jackendoff 1977, 192) |

However, Jackendoff is quite explicit about not analyzing such examples as RNR “since the presumed sources would either have the wrong reading or be ungrammatical” (Jackendoff 1977, 192). This, however, presumes that (48a)–(48b) are the only possible sources for the RNR examples in (47a)–(47b), which we have seen is not the case.24

| (48) |

a. |

John avoided similar issues/the same man/men with the same birthday and Bill ignored similar issues/the same man/men with the same birthday. |

|

b. |

John whistled the same tune/at equal volumes/together and Mary hummed the same tune/at equal volumes/together. |

|

|

(Jackendoff 1977, 192) |

This is consistent with Abels’ (2004) observation that internal readings are also impossible in VP ellipsis, as shown in (49a)–(49b).

| (49) |

a. |

John sang two quite different songs and Mary did, too. |

|

b. |

John sang (together) (at {equal/similar/different} volumes) and Mary did, too. |

|

|

(Abels 2004, 55) |

3.1.7 Right Edge Restriction

One of the most unique properties of RNR is the so-called Right Edge Restriction. There are many other formulations (and names) for this restriction: Right Edge Generalization (Abels 2004), Right Edge Effect (Johnson 2007), and Right Edge Condition (Wilder 1999), to name a few. I give Sabbagh's (2007) formulation in (50), as it remains nicely agnostic about the source of RNR.25,26

| (50) |

In the configuration: |

|

[[A….X…] Conj [B…X…]] |

|

X must be rightmost within A and B before either (i) X can be deleted from A; (ii) X can be rightward ATB‑moved; or (iii) X can be multiply dominated by A and B. |

|

(Sabbagh 2007, 356) |

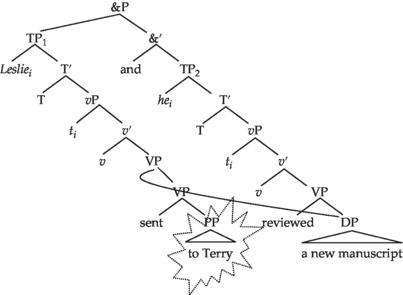

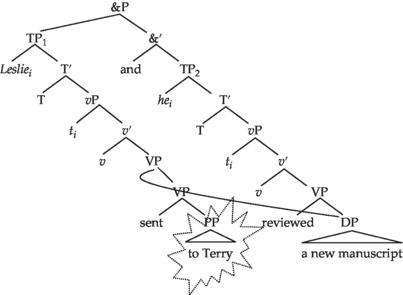

The contrast in (51a)–(51b) can thus be attributed to a violation of this restriction. (51a) is grammatical because the pivot corresponds to the rightmost gap inside each conjunct, whereas (51b) is not, due to the presence of the PP ‘to Terry’ in the first conjunct.

| (51) |

a. |

Leslie wrote ____, and Terry reviewed ____, a new manuscript. |

|

b. |

*Leslie sent ____ to Terry, and he reviewed ___, a new manuscript. |

However, the Right Edge Restriction can be obscured by the presence of rightward movement inside the conjunct (such as Heavy NP Shift or extraposition) feeding RNR. This is presumably what happens in (52):

| (52) |

Leslie has already sent ti to Paris ____, and Terry will soon send ti to London ____, the best designs from the spring collection. |

Even though the Right Edge Constraint does not bear directly on the ex-situ versus in-situ approach to RNR, any descriptively adequate approach to RNR has to capture it. One question to ask, then, is whether the ex-situ (movement) approaches or in-situ (ellipsis or multidominant) approaches are better suited to handle it. It is not generally the case that movement needs to target peripheral elements; leftward ATB movement is not limited to leftmost elements, thus there is no reason to expect that rightmost ATB movement (which is what RNR reduces to on a movement account) should be subject to such a restriction. It is also not generally the case that ellipsis has to target peripheral elements. Consider gapping, for example. If anything, it becomes ungrammatical if the gapped verb is right-peripheral:

| (53) |

a. |

Terry eats beans and Leslie eats rice. |

|

b. |

*Terry eats beans and Leslie eats. |

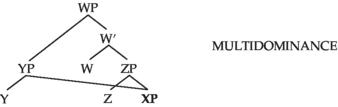

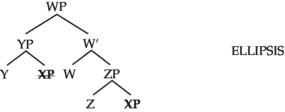

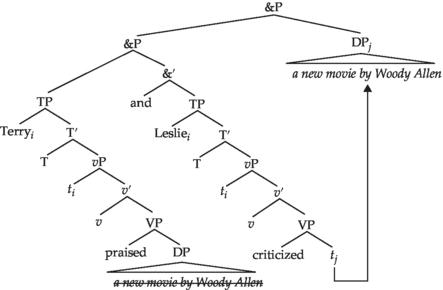

However, on many existing multidominant approaches to RNR (e.g. Wilder 1999; Fox and Pesetsky 2007; Johnson 2007; Gračanin-Yuksek 2013), the right peripherality of RNR falls out from linearization considerations. In most general terms, on these approaches, if the pivot is not the rightmost element in its conjunct, the structure cannot be linearized. Let me illustrate with Wilder's approach. The ungrammatical example (51b), repeated as (54a), has the structure in (54b).27

| (54) |

a. |

*Leslie sent ____ to Terry, and he reviewed ____, a new manuscript. |

|

b. |

|

Within the first conjunct, the DP pivot ‘a new manuscript’ is going to c-command (and thus precede, given the LCA) the PP ‘to Terry’. However, since the first conjunct (TP1) c-commands the second conjunct (TP2), this PP should also end up preceding the pivot, since anything contained inside the first conjunct will end up preceding anything contained in the second conjunct. This leads to a violation of antisymmetry, with the PP ‘to Terry’ both preceding and following the DP ‘a new manuscript’. Consequently, the structure cannot be linearized. The problem does not arise if there is no PP inside the first conjunct; the pivot is not going to c-command anything inside the first conjunct.

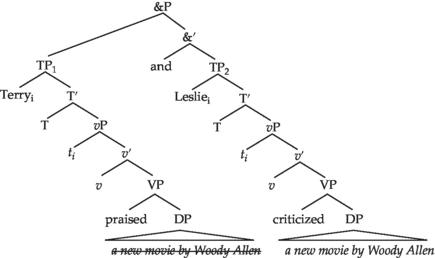

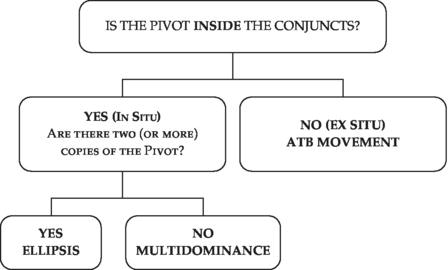

To sum up briefly, we have seen in this section the data that bear on the choice between ex-situ versus in-situ approaches to RNR. We have seen that the behavior of RNR with respect to islands, stranding, and binding point toward the in-situ approach, whereas scope and the behavior of RNR with respect to some constraints on movement seem to point in the opposite direction. In section 3.2, we turn to the issue of what kind of in-situ approach to RNR captures best the properties of this construction. Here the choices are between ellipsis and multidominance, the major difference between them lying in the number of the copies of the pivot.

3.2 One copy versus two copies

3.2.1 Morphological (mis)matches

It is well-known that ellipsis allows certain inflectional mismatches (see e.g. Sag 1976; Lasnik 1995; Potsdam 1997). Bošković (2004/1996) points out that the same inflectional mismatches that are possible in VPE are possible in RNR, as shown in (55a)–(55b). And, conversely, the mismatches that are impossible in VPE are also impossible in RNR, as shown in (56a)–(56b).

| (55) |

a. |

John has slept in her house, and now Peter will sleep in her house. |

|

|

(VPE: slept/sleep) |

|

b. |

John has slept in her house, and Peter definitely will, sleep in her house. |

|

|

(RNR: slept/sleep) |

| (56) |

a. |

*John won't enter the championship, but Jane is entering the championship. |

|

|

(VPE: enter/entering) |

|

b. |

*John is entering the championship, but Jane won't, enter the championship. |

|

|

(RNR: entering/enter) |

|

|

(Bošković 2004/1996, 15) |

Crucially, ATB movement does not allow analogous mismatches:

| (57) |

a. |

*[Sleeping in her office]i, (Peter was ti and) John will ti. |

|

b. |

*[Slept in her house]i, (John has ti and) Peter will ti. |

|

c. |

*[Questioning our motives]i, (John may be ti and) Peter hasn't ti. |

|

|

(Bošković 2004/1996, 16) |

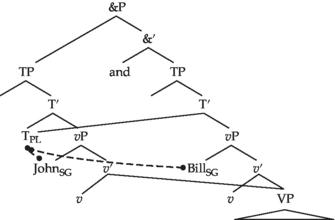

These kinds of mismatches favor an ellipsis analysis in which there are two copies of the pivot and one gets deleted under (less than perfect) identity with the other. Interestingly, other types of morphological mismatches favor an analysis with one copy of the pivot. Taken together with the evidence we saw in section 2 pointing toward the low position of the pivot, they favor an analysis in which the pivot is multiply dominated by material inside the two conjuncts. The relevant examples involve what Grosz (2015) dubs cumulative agreement and Yatabe (2003) summative agreement, which refers to plural agreement with two singular DPs, also discussed by Postal (1998). (58) provides an illustration.28

| (58) |

Sue's proud that Billsg ____, and Mary's glad that Johnsg ____, havepl/?*hassg traveled to Cameroon. |

|

(Grosz 2015, 6) |

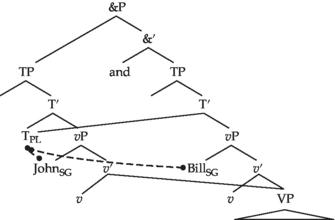

For Grosz (2015), cumulative agreement of this sort is due to a single head (T in this case) being shared between the two conjuncts. The T head in such a sharing configuration can undergo Multiple Agree (i.e. Agree between a single Probe and two Goals, proposed by Hiraiwa 2001) with two singular DP subjects simultaneously, which is what gives rise to cumulative agreement.

| (59) |

|

Interestingly, sometimes instead of the cumulative agreement we have just seen, the pivot agrees with the closer (i.e. the second) conjunct. This is, for example, what Kluck (2009) shows for Dutch. Kluck (2009) examines agreement with verbal pivots in Dutch and shows that even though matching (i.e. the situation in which the verb matches both conjuncts) is the norm (expected on a multidominant account), non-matching is sometimes possible. In such cases, there is a preference for the pivot to agree with the second (closer) conjunct. In (60a)–(60b), I provide examples from Polish to illustrate this proximity effect. It can be seen with both verbal and nominal pivots (for a discussion of the latter, see also Citko 2011a; 2011b). In (60a) the subject of the second conjunct determines agreement on the verbal pivot, and in (60b) the verb inside the second conjunct determines case on the nominal pivot.29

| (60) |

a. |

Maria |

myśli, |

że |

ona ____, |

a |

Jan |

myśli, |

że |

on ____, |

|

|

Maria |

thinks |

that |

she |

and |

Jan |

thinks |

that |

he |

|

|

był/*byłanajlepszym składniowcemnanaszymwydziale. |

|

|

was.m/*f best syntactician on our department |

|

|

‘Maria thinks that she, and Jan thinks that he, was the best syntactician in our department.’ |

|

b. |

Jan |

polubił ____, |

a |

wszyscy |

inni unikali |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jan |

likedacc |

and |

all |

others avoidedgen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

nowego kolegi/*nowego kolegȩ. |

|

|

new.gen/*acc colleague.gen/*acc |

|

|

‘Jan liked, but everyone else avoided, the new colleague.’ |

Sabbagh (2007) points out a similar proximity effect with respect to NPI-licensing:

| (61) |

a. |

%John immensely enjoyed ____, but few other people liked ____, any of the talks onRNR. |

|

b. |

*Few people liked ____, but John immensely enjoyed ____, any of the talks on RNR. |

|

|

(Sabbagh 2007, 363, fn. 11) |

And An (2007) observes a similar proximity effect with respect to the distribution of honorific agreement in Korean (and Japanese). He notes that in RNR, honorific agreement is possible if the subject of the second conjunct is socially superior to the speaker but not when the subject of the first conjunct is:

| (62) |

Korean |

|

a. |

Tomo‑nun |

bap‑ul, |

kuliko |

kyoswunim‑un |

ppang‑ul, |

|

|

Toma‑top |

rice‑acc |

and |

professor‑top |

bread‑acc |

|

|

Nina‑ekeycwu‑si‑ess‑ta |

|

|

Nina‑dat give‑hon‑past‑dec |

|

|

‘Tomo (gave) rice (to Nina) and Professor gave bread to Nina.’ |

|

b. |

*kyoswunim‑un |

ppang‑ul, |

kuliko |

Tomo‑nun |

bap‑ul, |

|

|

professor‑top |

bread‑acc |

and |

Tomo‑top |

rice‑acc |

|

|

Nina‑ekeycwu‑si‑ess‑ta |

|

|

Nina‑dat give‑hon‑past‑dec |

|

|

(An 2007, 119–120) |

3.2.2 Strict versus sloppy identity

The next set of data that bears on the choice between a structure with a single copy of the pivot and a structure with multiple copies thereof comes from the distribution of strict versus sloppy identity readings. Ha (2006; 2008) points out the following parallelism between ellipsis and RNR: in both of them, pronouns are similarly three-way ambiguous. The ambiguity is between a strict reading, a sloppy reading, and what Ha refers to as a third-party reading.

| (63) |

John likes his father, and Bill does like his father, too. |

VPE |

|

a. |

John likes John's father and Bill likes John's father, too. |

strict reading |

|

b. |

John likes John's father and Bill likes Bill's father, too. |

sloppy reading |

|

c. |

John likes Chris’ father and Bill likes Chris’ father, too. |

third‑partyreading |

|

|

(Ha 2008, 11) |

| (64) |

John likes ____, but Bill hates ____, his father. |

RNR |

|

a. |

John likes Bill's father, but Bill hates Bill's father. |

strict reading |

|

b. |

John likes John's father, but Bill hates Bill's father. |

sloppy reading |

|

c. |

John likes Chris’ father, but Bill hates Chris’ father. |

third‑party reading |

|

|

(Ha 2008, 11) |

3.2.3 Vehicle change effects

Ha also points out that RNR exhibits vehicle change effects, a property that is typically associated with ellipsis rather than movement or multidominance. We see this with respect to binding and negative polarity item licensing. (65a) is an example of VP ellipsis, in which the R-expression John is ‘replaced’ by a pronoun to avoid a Principle C violation. (65b) shows that the same is possible in RNR.

| (65) |

a. |

Sue said Bill wrote a mean joke about Johni on the blackboard, and hei told us that Mary did write a mean joke abouthimi, too. |

VPE |

|

b. |

Hei hopes Susan WON'T firehimi, but the secretary knows that she WILL, fire Johni at the end of this year. RNR |

|

|

(Ha 2008, 10) |

The examples in (66a)–(66b), also due to Ha (2008, 81), show analogous vehicle change effects with respect to NPI-licensing.

| (66) |

a. |

Mary didn't read any of the articles, but John did. |

|

b. |

John read ____, but he hasn't understood ____, any of my books. |

Considerations of this sort lead Ha to argue in favor of an ellipsis account. However, we have seen a number of problems for such an account, such as the lack of equivalence between the (a) and (b) examples in (67)–(68).

| (67) |

a. |

I borrowed ____, and my sisters stole ____, a total of $3000 from the bank. |

|

b. |

I borrowed a total of $3000 from the bank, and my sisters stole a total of $3000 from the bank. |

| (68) |

a. |

John gave Mary ____, and Joan presented to Fred ____, books that looked |

|

|

remarkably similar. |

|

b. |

John gave Mary books that looked remarkably similar, and Joan presented to Fred books that looked remarkably similar. |

|

|

(Abbott 1976, 642) |

Another potential issue for ellipsis accounts of RNR concerns the directionality of ellipsis. It is not clear why, given the existence of backward deletion (which is what RNR amounts to), forward deletion is not possible. If anything, in head-initial languages, other attested cases of ellipsis (gapping, sluicing, VP ellipsis, and pseudogapping) typically operate in a forward (not backward) fashion.

| (69) |

a. |

Bill praised a new movie by Woody Allen and Pat criticized a new movie by Woody Allen. |

|

b. |

*Bill praised a new movie by Woody Allen and Pat criticized a new movie |

|

|

by Woody Allen. |

And, lastly, if RNR is ellipsis, we might expect it to be limited to coordination. This is not the case, as shown by the following examples from Hudson (1976):

| (70) |

a. |

Of the people questioned, those who liked ____ outnumbered by two to one those who disliked ____ the way in which the devaluation of the pound had been handled. |

|

b. |

I'd have said he was sitting on the edge of ____ rather than in the middle of ____ thepuddle. |

|

c. |

It's interesting to compare the people who like ____ with the people who dislike ____ the power of the big unions. |

|

|

(Hudson 1976, 550) |

3.2.4 Conflicting requirements

In this chapter, we have seen both data that point toward a single multiply dominated copy of the pivot in an RNR construction and data that point toward more than one copy. This apparent contradiction leads Barros and Vicente (2011) to propose what they dub an eclectic theory of RNR, in which there is no single structure and derivation for RNR. They argue that both ellipsis and multidominance are possible sources for RNR. More specifically, they take morphological mismatches and vehicle change effects to be only compatible with an ellipsis account, and cumulative agreement and internal readings of relational modifiers to be only compatible with a multidominant account. What Barros and Vicente (2011) further point out is that when the properties associated with ellipsis (vehicle change or morphological mismatches) are combined with the properties associated with multidominance (cumulative agreement and relational modifiers) in a single RNR construction, the result is ungrammatical. The conflicts they examine are represented schematically in (71).

(71)

|

Cumulative Agreement |

Relational Modifiers |

Vehicle Change |

Morphological Mismatches |

| Cumulative agreement |

|

√ |

* |

* |

| Relational modifiers |

√ |

|

* |

* |

| Vehicle change |

* |

|

|

√ |

| Morphological mismatches |

* |

|

√ |

|

The examples in (72) are modeled upon Barros and Vicente's (2011) examples. The paradigm in (72a)–(72b) shows the interaction of relational modifiers and morphological mismatches; (72a) shows that the internal reading of relational modifiers is possible in RNR, and (72b) shows that cu5mulative agreement is likewise possible. We have seen similar examples in sections 3.1.6 and 3.2.1, respectively. However, when the two are put together in (72c), the internal reading of different disappears.

| (72) |

a. |

Terry wants to ____ but Leslie refuses to ____, work on different languages. |

|

b. |

Terry has ____, and Leslie will ____, work on a new language. |

|

c. |

Terry has ____, and Leslie will ____, work on different languages. |

Larson (2012), however, shows such conflicts do not always result in ungrammaticality, which suggests that there must be a way to account for morphological mismatches in a way that does not necessarily rely on ellipsis. The examples in (73a)–(73b) confirm this intuition: they combine wide-scope interpretation of the pivot (which is indicative of a movement or a multidominant structure) with a morphological mismatch (which is indicative of ellipsis). Interestingly, the result is grammatical, contra the prediction made by the eclectic account. In both cases, inverse scope is possible.

| (73) |

a. |

Some woman must ____, and some man ought to be ____, working with every student. |

(Larson 2012, 149) |

|

b. |

Every professor must have ____, and every research assistant should ____, work on a famous RNR puzzle. |