The relationship between risk factors and medication adherence among breast cancer survivors: What explanatory role might depression play?

Abstract

Objective

Despite the efficacy of clinical treatments (eg, adjuvant hormonal therapy) for breast cancer survivors (BCS), nonadherence rates remain high, increasing the risk of recurrence and mortality. The current study tested a theoretical model of medical nonadherence that proposes depression to be the most proximal predictor of medical nonadherence among BCS.

Methods

Breast cancer survivors were recruited from radiation clinics in Missouri. Survey data were collected 12 months after the end of primary treatment. The sample size included 133 BCS.

Results

Findings show substantial support for the model, demonstrating that depression mediated the relation between physical symptoms, cognitive symptoms, social support, and adherence to medication. This finding was replicated with a measure of mood disturbance.

Conclusions

These findings support the prediction that medication nonadherence among BCS multiply determined process and have compelling implications for healthcare providers and interventions designed to increase medication adherence among BCS.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2010, the costs of healthcare, in the USA, surpassed $2.7 trillion, with an estimated $100 billion to $300 billion of the costs attributed to medication nonadherence.1 Medical nonadherence, or patients' reluctance to follow a prescribed treatment plan,2 has significant effects on health, estimated to cause up to 10% of hospitalizations as well as an increase in morbidity and mortality.3-5 Conversely, among the general population, patients who adhere to their treatment and medication regimes are more likely to experience a variety of favorable outcomes.4, 6 Despite numerous interventions designed to improve patient adherence, nonadherence is a persistent problem.7, 8

Because treatments significantly reduce mortality rates for breast cancer survivors (BCS),9 it is important to maximize risk-reducing behaviors and quality of life (QOL).10, 11 Critical to survivorship care is adjuvant hormonal therapy that significantly reduces the prevalence and recurrence of invasive breast cancer (BC).12, 13 Consistent with these findings, BCS who adhere to their treatment plan are less likely to experience recurrence and have a greater chance of survival.14, 15 Notwithstanding the efficacy of these treatments, nonadherence rates range from 25% to 50%,10 substantially increasing the risk of recurrence and mortality among BCS.14, 15 The purpose of the current investigation is to understand the factors that predict nonadherence to medication regimens, particularly among BCS.

Although a wealth of research has elucidated the risk factors associated with nonadherence for BCS,10, 16 few studies have examined the manifestation of medication adherence (MA) as a process. On the basis of their review of major depression disorder among BCS, Fann et al17 developed a process model, which proposes that medical nonadherence as well as decreased family cohesion is determined by a number of interrelated factors, which in turn, decreases overall QOL. This model posits that depression is a consequence of a variety of treatment-related (eg, physical functioning) and psychosocial (eg, social support and psychological well-being) factors and is the single greatest predictor of medical nonadherence and decreased family cohesion. Fann et al17 provides a useful model for understanding the causes and consequences of treatment nonadherence in BCS. Although promising, as far as we know, no study to date has tested this model. Given the rates of medical nonadherence in BCS, the current investigation used an existing data set (published article will be referenced) to test the model of Fann et al17 regarding medication nonadherence, in particular.1

In accordance with the model of Fann et al,17 previous research supports that psychological and physical functioning are associated with medication nonadherence among BCS. Cognitive dysfunction (eg, forgetfulness and fatigue) are linked to higher levels of medication nonadherence in BCS.16, 18 In a review of studies on the nonadherence in BCS, Murphy et al10 determined that increased severity of physical (eg, menopausal symptoms and arthralgia) and cognitive side effects predicted nonadherence among BCS. These findings provide support that medication nonadherence among BCS is due to a range of factors, yet do not provide an adequate test of the mediating process model of Fann et al.

The model of Fann et al17 illustrates that physical and cognitive functioning influence depression among BCS, in turn, magnifying the relationship between depression and medical nonadherence. That is, depression is the more proximal predictor in the process. Studies have found a strong link between physical pain and depression among BCS.19, 20 Additionally, Demissie et al21 found that BCS who reported being depressed, as well as those who reported that they had experienced side effects of Tamoxifen, were more likely to discontinue taking it. The research of Bender et al22 shows general support for aspects of the model of Fann et al. The results of their study of BCS showed that the level of depression, measured prior to endocrine therapy, predicted nonadherence. In addition, both greater severity of physical symptoms and self-reported cognitive symptoms were associated with therapy nonadherence. The researchers, however, did not provide a test of the processes (ie, mediation) specified in the model of Fann et al.

The model of Fann et al17 also specifies that psychosocial functioning influences depression among BCS. Several reviews of medication nonadherence among BCS point to psychosocial factors as predictors but reveal that these factors are under studied.10, 23 Nevertheless, research documents the importance of psychosocial variables for psychological adjustment. For example, studies have shown that inadequate social support is associated with depression among BCS.10, 24-26 In addition, BCS with higher internal locus of control (ILC) is associated with lower depression.27 Given these findings, it is feasible that, akin to physical and cognitive functioning, these psychosocial variables have a distal influence on MA, through their association with depression.

Although these studies support the model of Fann et al,17 we know of none that have provided a test of whether depression mediates the associations between nonadherence and functioning (ie, cognitive, physical, and psychosocial), limiting conclusions about MA as a process. As such, it is important to more comprehensively test the model to advance our understanding of MA among BCS. On the basis of survey responses from a sample of BCS, we derived a variety of candidate variables, including physical and cognitive functioning as well as social support and internal ILC, and a measure of MA. We sought to test mediation with a measure of depression and to provide a replication of this mediation with a measure of mood disturbance. Following from the model of Fann et al,17 we hypothesized that poorer physical and cognitive functioning as well as lower social support and ILC would each uniquely predict MA. Also, we hypothesized that greater physical and cognitive dysfunction as well as insufficient social support and lower ILC would be associated with greater depression. Furthermore, we predicted that the relationship between MA and physical and cognitive functioning would be mediated by depression. Finally, we predicted that this mediation pattern would be replicated using a measure of mood disturbance.

2 METHOD

2.1 Procedure

The data used to test the model of Fann et al were derived from 1 measurement period of a larger longitudinal study of female BCS. Survivors were recruited from 9 radiation clinics in Missouri. Eligible patients were (1) female, (2) 18 years of age or older, (3) undergoing radiation treatment at one of the participating clinic sites, and (4) English-speaking. Of the participants, 79% had completed chemotherapy treatment by the second assessment, 15% did not have chemotherapy, and for 6%, this information was not reported. Eligible BCS were mailed surveys 12 months after the end of radiation treatment.

2.2 Participants

Of the 203 BCS that completed this survey, 133 reported being prescribed with antiestrogen or estrogen-inhibiting medication (eg, aromatase, novladex, and tamoxifen) and completed the measure of MA; these 133 BCS comprise the sample for the current investigation. Those who were included in the current sample differed significantly on only the cognitive symptoms measure; those in the current sample reported somewhat less severe cognitive symptoms, M = 2.97, than the remaining, 3.41, t(190) = −1.99, P < .05. No other significant differences were found for the primary and demographic variables (all t values < 1.34, all χ2 < 9.46, and all Ps > .05).

Participants were asked about their total household annual income, the categories were organized in increments of $10 000 from less than $15 000 to $115 000 or more (eg, less than $15 000, $15 000-$25 000, etc). Just over half of the sample reported household incomes between of $65 000 or less (57.9%), 29.3% reported incomes greater than $65 000, and 12.8% chose to not respond. The participants were asked to report the diagnosed stage of their BC: Stage 0 = 0.8%, Stage I = 40.6%, Stage II = 25.6%, Stage III = 11.3%, Stage IV = 3.8%, and 11.3% reported not knowing the stage (6.8% were missing). One hundred twenty-four participants identified as White (93.2%), 3.8% identified as African-American, Asian-American, American-Indian, or other (3% were missing). The majority of participants were married or cohabitating (69.2%), 11.3% were divorced, 4.5% were single, 11.3% were widowed, and 2.3% reported “other” (1.5% were missing). The average age was 68.4 years (SD = 12.74 years).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale

The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression28 was used. The scale has been used, often, in studies of cancer survivors27 and assessed the regularity of depressive symptoms, using a 4-point scale (1, “Rarely or none of the time” [less than1 day]; 4, “Most or all of the time” [5-7 days]). Example items include, “I felt depressed” and “I could not get going.” An average score was calculated (α = .92).

2.3.2 Profile of Mood States scale

The 35-item Profile of Mood States29 scale was used to measure mood disturbance because of its wide use in studies of cancer patients.26 The Profile of Mood States questionnaire assesses 6 mood subscales: tension-anxiety, depression, anger-hostility, vigor, fatigue, and confusion in a 5-point format (0, “Not at all”; 4, “Extremely”). Mood disturbance scores were computed by adding the totals of 5 negative-mood subscales and subtracting the vigor total (α range = .83-.94) Higher scores indicated greater mood disturbance.

2.3.3 Medication Adherence scale

Participants were asked if they were taking an antiestrogen medication (eg, aromatase, novladex, and tamoxifen) as part of your BC treatment (yes or no). We used Morisky, Green, and Levine's30 Medication Adherence scale because of its feasibility, reliability, and validity for measuring adherence. Four items assessed whether participants adhered to the medications used as a part of their BC treatment. Participants responded using a 5-point scale (1, “Very often”; 5, “Never”); a higher average score represented greater adherence (α = .71).

2.3.4 Physical and cognitive symptoms

The survey included 20 symptoms based on their appropriateness for the sample.31, 32 Participants were asked to report the severity of these symptoms during the last month. The scale was a 7-point scale (1 = “Not at all” to 7 = “Severe”). Seventeen of the symptoms were physical in nature (eg, chest wall pain and swelling of the arm). The average of these items was used as an indicator of severity of physical symptoms (α = .78). Three were cognitive symptoms (eg, forgetfulness and difficulty in concentrating). The average of these items were the indicator of severity of cognitive symptoms (α = .82).

2.3.5 Psychosocial variables

Participants' perceptions of social support from 5 sources (ie, spouse/partner, female family members, other family members, friends, and community members) were assessed.33 We adopted this measure of social support because it was developed for use with BCS and it allowed participants to assess social support from a variety of sources. For each source, 4 items assessed level of social support (eg, How much do you feel you can count on your [source] to perform daily chores?). A 6-point scale was used (1 = “Not at all”, 6 = “A lot”); an average score was calculated across all sources (α = .78). The measure of internal health ILC,34 which is 1 subscale in the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control assessment and is used with patient populations.27 It is comprised of 6 items (eg, My physical well-being depends on how well I take care of myself.), with a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The reliability of this scale was unacceptably low (α = .34).

3 RESULTS

We adopted Baron and Kenny's31 analytical method to test mediation, using regression analyses. First, we conducted correlational analyses to determine if the distal predictor variables were associated with depressive symptoms. Next, for those predictors that were correlated with the outcomes, we conducted a regression analyses to determine if each uniquely predicted MA and the hypothesized mediator (ie, depressive symptoms). Finally, to test mediation, we entered the predictor variables as well as the hypothesized mediator in a single regression model with medicine adherence as the endogenous variable. To assess replication of our primary findings for depressive symptoms, we used this same mediational approach but with mood disturbance as the mediator. Household income and relationship status (recoded as divorced/single/widowed/other = 0, married/cohabitating = 1) were the only demographic variables correlated with any of the primary variables: depressive symptoms, rs = −0.33, −.37, Ps < .05, mood disturbance, rs = −0.26, −.22, Ps < .05, and social support, rs = 0.22, .21, Ps < .05, respectively. In general, the correlations suggest that higher income as well as being in a married or cohabitating relationship were correlated with less depressive symptoms and mood disturbance and with higher social support. These demographic were included as control variables in all regression analyses.2

3.1 Correlational analyses

As shown in Table 1, many of the hypotheses derived from the model of Fann et al17 were supported by the zero-order correlations. Specifically, cognitive symptoms and physical symptoms were associated with MA, showing greater symptoms were associated with less adherence. Also, higher levels of social support were associated with greater MA. Most likely, due to its low reliability, the measure of health ILC was only marginally associated with adherence. Because ILC was not significantly associated with MA, it was not included in our tests of the model of Fann et al. The correlations also showed that cognitive and physical symptoms were associated with greater depressive symptoms and social support was associated with less frequent symptoms. These findings suggested that depressive symptoms may play a mediating role, as hypothesized. The pattern of correlations found for depressive symptoms was replicated for mood disturbance.

| Primary variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Medication adherence | .71 | ||||||

| 2. Depression | −.37** | .92 | |||||

| 3. Mood disturbance | −.39** | .84** | .83-.94 | ||||

| 4. Physical symptoms | −.33** | .43** | .45** | .82 | |||

| 5. Cognitive symptoms | −.34** | .50** | .61** | .54** | .82 | ||

| 6. Social support | .22** | −.29** | −.27** | −.06 | −.17 | .78 | |

| 7. Internal locus of control | .02 | −.27** | −.24** | .24** | −.14 | −.06 | .34 |

| Means (SD) | 2.97 (1.23) | 1.52 (.50) | 7.99 (18.8) | 2.06 (.70) | 2.97 (1.23) | 4.20 (1.14) | 3.71 (.75) |

- Reliabilities are on the diagonal.

- * P < .05,

- ** P < .01

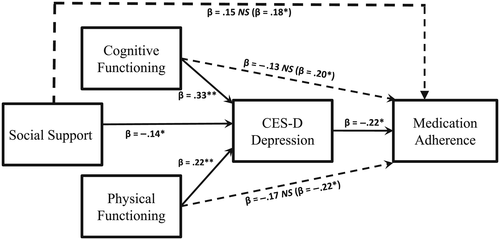

As explained in the previous section, the first step of the mediational analyses was to determine whether cognitive functioning, physical functioning, and social support uniquely predicted MA in a single regression model.31 Consistent with the hypotheses, the results showed that cognitive functioning, β = −.20, t(127) = −2.06, P < .05, and physical functioning, β = −.22, t(127) = −2.23, P < .05, uniquely predicted lower levels of MA, and social support uniquely predicted greater adherence β = .18, t(127) = 2.11, P < .05. The next step was to determine whether these 3 variables uniquely predicted the proposed mediator. In a single regression analysis, cognitive symptoms, β = .33, t(127) = 4.01, P < .001, and physical symptoms, β = .22, t(127) = 2.72, P < .01, uniquely predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms, and social support uniquely predicted lower depression, β = −.14, t(127) = −2.05, P < .05.

The final step in the mediational analyses was to determine whether the association between cognitive and physical symptoms and MA was explained by depressive symptoms. As shown in Figure 1 and as hypothesized, the findings revealed that MA was the outcome variable, and depressive symptoms (ie, mediator), β = −.22, t(127) = −.211, P < .05, were entered into a regression equation simultaneously with the 3 predictor variables: cognitive symptoms, β = −.13, t(127) = −1.26, P < .30; physical symptoms, β = −.17, t(127) = −1.72, P < .10; and social support β = .15, t(127) = 1.73, P < .10, no longer remained as significant predictors supporting depressive symptoms as a mediating variable. These findings provide support for the model of Fann et al.17

Replicating these findings, mood disturbance was also predicted by cognitive symptoms, β = .48, t(126) = 6.10, P < .001; physical symptoms, β = .17, t(126) = 2.13, P < .05; and social support, β = −.13, t(126) = −1.96, P < .06. But the association for social support did not reach conventional levels of significance. Also, the mediational findings for depression were replicated when mood disturbance was entered into a mediational model. This analysis showed that only mood disturbance remained as a significant predictor of MA, β = −.22, t(126) = −2.08, P < .05, in a model that also included cognitive symptoms, β = −.09, t(126) = −.85, P < .40, physical symptoms, β = −.18, t(126) = −1.76, P < .10, and social support, β = .15, t(126) = 1.76, P < .10. The results for mood disturbance replicate the findings for depression, further supporting the model of Fann et al.17

4 DISCUSSION

The primary objective of the current study was to provide an integrative test of the theoretical model17 of medical nonadherence among BCS. Consistent with the model of Fann et al,17 poor cognitive and physical functioning predicted lower levels of adherence to medication among BCS. The results showed that cognitive and physical functioning indirectly decreased the likelihood a BCS will comply with their medication regime. Furthermore, the current findings show that cognitive and physical functioning have distinct influences on MA as shown in previous research,10, 29 but these studies rarely measure both constructs and examine whether each uniquely predicts adherence. The present results are among the first to reveal that both variables uniquely contribute to adherence.

The findings also showed that perceived social support was a unique predictor of MA, supporting the hypothesis of Fann et al17 that psychosocial variables play an important role in MA. A recent review of adherence to treatment in BCS indicates that the contribution of psychosocial factors to nonadherence has been given limited attention10 and as such the present findings provide some initial evidence of the contribution that psychosocial factors may play. In particular, our findings suggest that having relatively high levels of social support may make it easier for cancer survivors to adhere with medication. Distinct from previous findings,31 our results failed to reveal an association between ILC and MA, but this lack of association was likely because of the unexpectedly low reliability.

Cognitive and physical symptoms as well as lack of social support were unique predictors of greater depressive symptoms, and this relationship was conceptually replicated with a measure of mood disturbance. Although these associations have been shown in the prior literature,10, 19, 20, 24 new to the literature are the findings of the current studies, which revealed that depression mediated the relationships between MA and physical and cognitive symptoms as well as social support. For example, these results suggest that social support may facilitate MA because social support reduces depression. These mediational findings provide support for the key prediction of Fann et al17 that specifies that depression is a more proximal explanatory mechanism of MA among BCS. Analogous to depression, this mediating pattern was replicated with a measure of mood disturbance.

Despite that previous studies10, 16, 21 have shown that a variety of variables influence MA, to our knowledge, the current study is the first to reveal that psychosocial factors as well as cognitive and physical functioning are distal predictors of MA and depression serves as the more proximal predictor of MA. Accordingly, the current findings suggest that the model of Fann et al17 has important implications for understanding the influence of depression on MA, even for BCS who are not clinically depressed.

4.1 Implications

The model of Fann et al17 and the results of our mediational analyses suggest that levels of depression are the most proximal predictor of MA. As such, medical professions should query patients about their experiences of depressive symptoms. Importance must be given to identification of whether a patient is experiencing symptoms after completion of primary treatment, because the patient will necessarily have less regular support from medical personnel. Because even preclinical levels of depression can pose obstacles to MA, it is important that BCS receive clear guidance about the availability of psychotherapeutic services.

Moreover, the current results suggest that medical personnel should understand the influences that physical and cognitive functioning have on depression. Identification of deficits in physical and cognitive functioning may signal the possibility that a patient is experiencing symptoms of depression. For these BCS with deficits in physical and psychological functioning, it may be especially important to assess depressive symptoms. Our results suggest evidence that it is important that medical personnel also consider BCS' psychosocial functioning. Analogous to previous suggestions,23 the current model highlights the importance of screening for psychosocial risk factors such as depression and insufficient social support in informing treatment decisions.

The model of Fann et al as well as the current results point to the complex processes that influence MA for BCS, in particular, and likely for other life-threatening illnesses. Although medication for depression may provide some relief, other variables that influence depression cannot be addressed by medication. For example, understanding whether BCS are at risk because they have inadequate social support or other sociocultural risk factors (eg, low income) will be important for identifying those who may not comply with medication regimens. Certainly, these findings underscore the importance of using psychotherapy in addition to medication therapy and serve to inform interventions designed to improve QOL among BCS.

4.2 Limitations and future research

Although our findings have implications for clinically depressed BCS, the current data were not specific to only BCS who were clinically depressed. Given that the model of Fann et al17 was derived from research on clinically depressed BCS, future studies should aim to replicate these findings for patients that meet the requirements of clinical depression. Second, the model of Fann et al17 included several other variables (eg, family cohesion and QOL) for which we did not have candidate variables in our data. Future research should include all of the variables in the model to further elucidate the causes and consequences of treatment nonadherence. Next, this study did not account for other psychosocial variables (eg, caregiver and sociocultural influence) that could also influence the degree of MA in BCS. Examining other psychosocial variables is imperative to understanding the manifestation of medication nonadherence in BCS. Moreover, the current data used to test the model of Fann et al17 was cross-sectional and the sample size was relatively small (N = 133), limiting conclusions about the directionality and generalizability of the study findings. Given the effect that the time since treatment has on the BCS,24 future studies should replicate this model at different times after treatment to examine the consequences of treatment at different times and to clarify the direction of the relationships in the current model. Nonetheless, the current study sets a new precedent for research on MA; understanding of the manifestation of MA must be viewed as a multiply determined process.

ENDNOTES

- 1 We did not have a candidate measure that could be used as an operationalization of family cohesion, so we were unable to test predictions regarding family cohesion.

- 2 Because 17 of the 133 BCS refrained from reporting their household income, these missing data were imputed with the mean score. Relationship status was recoded such that those who were married or cohabitating were coded as 1 and all others were coded as 2.