Investment Duration and Corporate Governance†

Abstract

In this study we analyze the relation between institutional investment duration and corporate governance using a new metric of investment duration that accounts for firm-specific investment durations of each institution. We conjecture that institutional investors that hold a firm's shares for a longer duration have greater incentives and ability to influence the firm's governance structure. Consistent with this conjecture, we find that a broadly defined index of corporate governance increases with the duration of institutional ownership. We also show that the relation between investment duration and corporate governance varies across different types of institutions and across firms with different stock market liquidities.

1 Introduction

The role of institutional investors in various financial interactions has received increasing attention from both public media and academia as the level of institutional ownership in United States corporations has increased dramatically during the last two decades.1 In this study we investigate institutional shareholder activism by analyzing the relation between institutional investment duration (INVDUR) and a broadly defined index of corporate governance (CGINDEX).2 The extent to which institutional investors can influence a firm's governance structure is likely to depend on how long they have held the firm's shares because investment duration affects their incentives and abilities to influence corporate governance. Institutional investors with short investment duration have little incentive to spend resources on corporate governance because they are not likely to remain shareholders and capture future benefits. In addition, they have less time to learn about the firm and thus are less able to interfere with the firm's management due to the lack of expertise and knowledge.

Many institutions index a large portion of their portfolio. For example, Carleton et al. (1998) find that TIAA-CREF indexes 80% of its domestic equity portfolio. Large ownership and indexing strategy provide institutional investors with incentives to interfere with management and pursue an activist agenda because they cannot simply vote with their feet. Prior research finds evidence that institutional efforts to improve corporate governance and/or firm performance pay off because they bring benefits to shareholders. For instance, Brav et al. (2008) find that Schedule 13D filings by hedge funds with an activist agenda are associated with positive abnormal stock returns.3 Klein and Zur (2009) also find that firms targeted by activist institutional investors exhibit positive abnormal stock returns around the initial Schedule 13D filing date and over subsequent periods.4

Our study contributes to a growing literature that analyzes various ramifications of investment duration for corporate decisions and market valuation. Gaspar et al. (2005) find that firms held by short-term investors have a weaker bargaining position in acquisitions. Yan and Zhang (2009) analyze the relation between institutional trading and future earnings surprises and find that short-term institutions are better informed than long-term institutions. Cella et al. (2013) show that institutional investors with short trading horizons magnify the impact of market-wide negative shocks on share price. Derrien et al. (2013) hold that longer investor horizons attenuate the effect of stock mispricing on various corporate policies.5 Gaspar et al. (2013) examine how shareholder investment horizons influence payout policy choices and show that firms held by short-term investors make repurchases more often because they care mostly about the short-term price reaction. Harford et al. (2012) show that firms with longer investor horizons hold more cash and are more likely to invest in projects with long-term payoffs.

Despite the different roles of long- and short-term institutional investors in shareholder activism and their potential impact on corporate governance, prior research provides limited evidence on the issue. Chen et al. (2007) conjecture that only independent institutions with long-term investments make efforts to monitor and influence managers.6 In support of this conjecture, they show that only concentrated holdings by independent long-term institutions are related to post-merger performance and the presence of these institutions increases the probability of bad bid withdrawals. Attig et al. (2012) show that the sensitivity of corporate investment outlays to internal cash flows is lower with the presence of long-term institutional investors and interpret this result as evidence that long-term institutional investors have greater incentives to monitor managers. In a similar vein, Attig et al. (2013) show that the cost of equity decreases with the presence of long-term institutional investors. We extend the literature of investment duration (or horizon) by analyzing the impact of institutional investment duration on corporate governance.

Previous studies (e.g. Bushee, 1998; Gaspar et al., 2005) determine whether an institution is a long- or short-term investor based on the average turnover ratio or holding period of its entire portfolio of stocks. This method could be problematic because it considers an institution a short-term investor if its average turnover ratio is high although its turnover ratios for some stocks could be quite low. Generally, institutional investors hold a large number of stocks, and their investment strategies and holding periods vary considerably across stocks in their portfolio. An institution may be actively involved with a firm's management and governance as a long-term investor, but may be a passive investor with short investment horizons in other firms. The present study analyzes the effect of investment duration on corporate governance using a new metric that accounts for firm-specific investment durations of each institution. Specifically, we measure the mean institutional holding period for each firm across all institutions that hold its shares (instead of the mean holding period of each institutional investor for all stocks in its portfolio) and use it in our empirical analysis.

Our study differs from prior research also in that we employ a comprehensive measure of corporate governance. Many prior studies focus on whether institutional investors exert an influence on a single dimension of corporate governance, such as CEO compensation, CEO turnover, or anti-takeover practices.7 For example, Hartzell and Starks (2003) and Almazan et al. (2005) examine whether institutional ownership concentration is related to pay-for-performance sensitivity and the level of CEO compensation. Huson et al. (2001) analyze the relation between CEO turnover and institutional ownership. Bizjak and Marquette (1998) study shareholder proposals to rescind “poison pills.”

Shareholder proposals submitted by institutional investors usually cover a wide range of corporate governance issues. For example, Campbell et al. (1999) find that the shareholder proposals in their study sample cover 17 corporate governance related issues, including classified board, executive compensation, cumulative voting, sale of the company, poison pill, and board independence. Other studies (e.g. John and Klein, 1995; Wahal, 1996; Del Guercio and Hawkins, 1999; Gillan and Starks, 2000) report similar findings.8 To reflect that institutional shareholder activism may affect multiple dimensions of corporate governance, our study considers 50 governance standards that encompass the following seven categories: board, audit, charter/bylaws, state of incorporation, executive and director ownership, executive and director compensation, and progressive practices.

Prior research suggests that only certain types of institutional investors may play the role as an active monitor.9 For example, Almazan et al. (2005) find that pay-for-performance sensitivity is positively related to the ownership concentration of independent investment advisors and investment companies, and insignificantly related to that of bank trusts and insurance companies. They note that independent investment advisors and investment companies may have lower monitoring costs than bank trusts and insurance companies because the former group has better employee skills and ability to collect information, faces less regulatory restrictions, and make fewer business ties with corporations. Woidtke (2002) analyzes the valuation effects of public and private pension funds and reports that firm value is positively related to ownership by private pension funds and negatively related to ownership by public pension funds. The present study examines whether the relation between corporate governance and investment duration varies across different types of institutions. In this respect, our study complements prior research that focuses on shareholder activism by a particular institutional investor, such as the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) or TIAA-CREF.10

We show that CGINDEX increases with the duration of institutional ownership (INVDUR), suggesting that institutional investors that hold a firm's shares for a longer period have greater incentives and abilities to influence the firm's governance structure. The relation between INVDUR and CGINDEX varies across different types of institutions and the relation is particularly strong for public pension funds. We show that the presence of large institutional investors with a long investment horizon increases the likelihood of a firm's adoption of the best governance standards that are related to audit, board structure, executive and director compensation, and progressive practices. In contrast, the presence of long-term institutional investors does not have an impact on the governance practices related to either anti-takeover or executive and director ownership structure. Finally, we find that longer INVDUR is more effective in improving the governance structure of firms with higher levels of stock market liquidity. We interpret this result as evidence that firms have greater incentives to improve their governance structure to retain long-term institutions, especially when the threat of exit is greater.

Our study contributes to the literature in several important dimensions. First, our study underscores the importance of the role of investment horizon in shareholder activism using a newly developed measure of institutional investment duration. Second, in contrast to prior research, we analyze the effect of institutional shareholder activism on a broadly defined index of corporate governance and show that institutional shareholder activism affects multiple dimensions of corporate governance. Finally, we shed further light on whether or not shareholder activism varies across different types of institutional investors and across firms with different levels of stock market liquidity.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 explains our data sources and variable measurement methods. Sections 3 through 6 present empirical results. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2 Data Sources, Variable Measurement Methods, and Descriptive Statistics

Our sample comprises publicly traded United States companies during the 9-year period from 2001 through 2009. The sample period starts from 2001 because the Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) provides corporate governance data from that year. We obtain financial and stock return data from Standard & Poor's Compustat and the Center for Research in Securities Prices (CRSP). We obtain institutional ownership data from Thomson Reuters’ Institutional (13F) Holdings. Following prior research, we exclude financial firms (SIC code from 6000 to 6999) and utility firms (SIC code from 4900 to 4949) from the study sample. We winsorize the variables at the 1% and 99% levels to minimize the effect of outliers. The final sample consists of 19 204 firm-year observations.

2.1 Corporate Governance Index

The ISS data contain more than 60 governance provisions in the following eight categories: board, audit, charter/bylaws, state of incorporation, executive and director ownership, executive and director compensation, progressive practices, and director education. We construct our yearly corporate governance index using 50 governance provisions in seven categories, including 17 provisions from board, four provisions from audit, eight provisions from charter/bylaws, 10 provisions from compensation, four provisions from ownership, six provisions from progressive practices, and one provision from state of incorporation.11 Appendix 1 provides the list of these governance provisions. We determine whether a particular governance standard is met using the minimum standard provided in ISS Corporate Governance: Best Practices User Guide and Glossary (2008).

Following prior studies, we create a governance index (CGINDEX) for each firm by awarding one point for each governance provision that satisfies the ISS standards.12 ISS collects data from proxy statements, which contain information on the firm's governance characteristics for the preceding year (Ciceksever et al., 2006). To account for the time lag in the ISS data, we assume that CGINDEX obtained from the ISS data in year t reflects the governance quality in year t−1 in our empirical analysis. For instance, CGINDEX obtained from the 2005 ISS data is considered CGINDEX in 2004.

2.2 Institutional Investment Duration (INVDUR)

Generally, institutional investors hold a large number of stocks and their investment strategies and lengths of investment duration vary across stocks. An institution could be actively involved with a firm's management and governance as a long-term investor, but may be a passive investor with a short investment horizon in other firms. Hence, classifying an institution into a short- or long-term investor in its entirety is problematic. To avoid this problem, we first measure an institution's investment duration for each stock in its portfolio separately and then determine whether a stock is held by long- or short-term institutional investors based on the mean investment duration across all institutions that hold the stock.

To determine the investment duration of institution k in stock i, we first identify the first quarter in which institution k reported its shareholding in firm i from the 13F data provided by Thomson Reuters. We then measure institution k's investment duration for firm i at the end of year t, INVDURkit, by the number of quarters between the first quarter and the last quarter of year t.

To shed some light on the extent to which an institution's investment duration differs across stocks in its portfolio, we classify stocks in each institution's portfolio into six different investment duration categories (0–1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 4–5, and above 5 years) and then calculate the proportion of stocks that belong to each category. Rows 1 through 7 in Table 1 show the mean proportion of stocks in each category for each type of institution and Row 8 shows the mean proportion across all institutions. The results show that public (private) pension funds hold 33% (32%) of stocks in their portfolios for more than 5 years and 24% (29%) of stocks for <1 year. In contrast, hedge funds hold 5% of stocks for more than 5 years and 62% of stocks in their portfolios for <1 year. On average, 12% of our sample stocks are held by institutional investors for more than 5 years and 48% of them are held by institutional investors for <1 year. These results indicate that, regardless of type, the investment duration of an institutional investor varies significantly across stocks in its portfolio and thus classifying an institution into a long- or short-term investor based on its average investment duration across all stocks it holds could be quite misleading.

| Investment duration (in years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 1–2 | 2–3 | 3–4 | 4–5 | >5 | |

| Bank trusts | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| Insurance | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| Investment companies | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| Investment advisors | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| Public pension funds | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.33 |

| Private pension funds | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.32 |

| Hedge funds | 0.62 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| All institutions | 0.48 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

- To determine the investment duration (INVDUR) of institution k in stock i, we first identify the first quarter in which institution k reported its shareholding in firm i from the 13F data provided by Thomson Reuters. We then measure institution k's investment duration for firm i at the end of year t, INVDURkit, by the number of quarters between the first quarter and the last quarter of year t. To shed some light on the extent to which an institution's investment duration differs across stocks in its portfolio, we classify stocks in each institution's portfolio into six different investment duration categories (0–1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 4–5, and above 5 years) and then calculate the proportion of stocks that belong to each category.

We measure the institutional investment duration of stock i in year t, INVDURit, by the weighted mean value of the investment duration of all institutions that hold stock i at the end of year t: INVDURit = ∑[wkit × log(INVDURkit)], where wkit is the fraction of firm i's total institutional ownership held by institution k at the end of year t and ∑ denotes the summation over k.13 We use the logarithm of INVDURkit because its distribution is highly skewed.

2.3 Control Variables

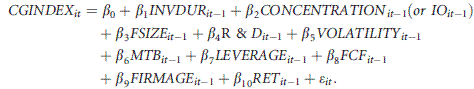

Institutions are likely to be effective in shareholder activism when their ownership is concentrated (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986). We measure institutional ownership concentration (CONCENTRATION) by the Herfindahl index and use it as a control variable. The Herfindahl index of firm i in year t is defined as Hit = 100 ∑Skt2, where Skt is the fraction of firm i's shares held by institution k in year t and ∑ denotes summation over k. We expect a firm with more concentrated institutional ownership (i.e. a greater Herfindahl index) to have a higher governance index. Institutions are also likely to be more effective in shareholder activism in a given firm when they hold a larger fraction of the firm's shares. Hence we use the total ownership of institutional investors (IO) for each firm as a control variable.

Prior research shows that corporate governance is related to a number of firm attributes. Dey (2008) employs various firm characteristics – organizational complexity, size, volatility in operating environment, ownership structure, leverage, and free cash flow – as proxies for agency conflicts and shows that firms with greater agency conflicts have better governance mechanisms in place. Ciceksever et al. (2006) employ firm size, investment opportunity, intangible assets, and income volatility as proxies for monitoring costs and show that companies with larger monitoring costs exhibit better governance structure. Similarly, Linck et al. (2008) view firm complexity and monitoring costs as determinants of corporate governance. They use firm size, debt ratio, and the number of business segments as proxies for firm complexity and the market-to-book ratio, R&D spending, and return volatility as proxies for monitoring costs. Klapper and Love (2004) show that corporate governance structure is significantly related to firm size, sales growth rate, and capital intensity.

In our empirical analysis, we include firm size, R&D expenditure, volatility in operating profit, market-to-book ratio, leverage, free cash flow, firm age, and stock returns as control variables. Firm size (FSIZE) is measured by the logarithm of total assets, R&D expenditure is scaled by total assets, volatility in operating profit (VOLATILITY) is measured by the standard deviation of operating profit in the past 5 years, market-to-book ratio (MTB) is measured by the ratio of the summation of the market value of equity and long-term debt to total assets, and leverage ratio (LEVERAGE) is measured by the ratio of long-term debt to total assets. Similar to Dey (2008), we measure free cash flow (FCF) by the difference between operating cash flow and capital expenditure scaled by total assets. Stock return (RET) is the buy-and-hold stock returns over the past 5 years.

Finally, we include firm age (FIRMAGE) as an additional control variable because firm age is likely to be correlated with both corporate governance and institutional investment duration. For example, Gillan et al. (2006) find that older firms are more likely to adopt anti-takeover amendments. The correlation between firm age and institutional investment duration can arise because institutional investors are likely to purchase shares of older firms earlier than younger firms. We measure firm age by the number of years since the firm first appeared in the CRSP database.

2.4 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

We present descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix of the variables in Table 2. Panel A shows that CGINDEX ranges from 1 to 42, with the mean (median) value of 24.4 (25). The mean (median) value of INVDUR is 2.5 (2.57) and the mean (median) value of institutions’ aggregate ownership is 46.9% (49.1%). Panel B shows that CGINDEX is positively correlated with INVDUR. CGINDEX is also positively correlated with institutional ownership concentration (CONCENTRATION), aggregate institutional ownership (IO), firm size (FSIZE), free cash flow (FCF), and firm age (FIRMAGE), and negatively correlated with R&D expenditures, volatility (VOLATILITY), market to book ratio (MTB), leverage (LEVERAGE), and past stock returns (RET).

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | Percentile | |||

| 25 | 50 | 75 | |||||

| CGINDEX | 24.40 | 5.19 | 1.00 | 42.00 | 21.00 | 25.00 | 28.00 |

| INVDUR | 2.50 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 3.76 | 2.13 | 2.57 | 2.93 |

| CONCENTRARION | 2.09 | 1.84 | 0.00 | 10.97 | 0.70 | 1.75 | 2.97 |

| IO | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 0.70 |

| FSIZE | 5.86 | 1.97 | 1.71 | 10.48 | 4.43 | 5.82 | 7.20 |

| R&D | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| VOLATILITY | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| MTB | 1.92 | 1.83 | 0.37 | 14.21 | 0.92 | 1.34 | 2.18 |

| LEVERAGE | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 1.06 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.34 |

| FCF | 0.01 | 0.21 | −1.24 | 0.35 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| FIRMAGE | 19.51 | 15.57 | 5.00 | 78.00 | 9.00 | 14.00 | 26.00 |

| RET | 1.08 | 2.49 | −0.96 | 14.30 | −0.35 | 0.33 | 1.45 |

| Panel B: Correlation matrix | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

| CGINDEX (1) | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| INVDUR (2) | 0.21*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| CONCENTRARION (3) | 0.14*** | 0.15*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| IO (4) | 0.27*** | 0.15*** | 0.68*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| FSIZE (5) | 0.27*** | 0.44*** | 0.23*** | 0.57*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| R&D (6) | −0.03*** | −0.15*** | −0.09*** | −0.17*** | −0.34*** | 1.00 | |||||

| VOLATILITY (7) | −0.08*** | −0.30*** | −0.15*** | −0.27*** | −0.42*** | 0.54*** | 1.00 | ||||

| MTB (8) | −0.08*** | −0.20*** | −0.11*** | −0.02*** | −0.19*** | 0.43*** | 0.41*** | 1.00 | |||

| LEVERAGE (9) | −0.02*** | 0.06*** | 0.03*** | −0.01 | 0.24*** | −0.16*** | −0.09*** | −0.14*** | 1.00 | ||

| FCF (10) | 0.08*** | 0.17*** | 0.12*** | 0.29*** | 0.39*** | −0.68*** | −0.57*** | −0.28*** | 0.02** | 1.00 | |

| FIRMAGE (11) | 0.20*** | 0.42*** | −0.05*** | 0.02*** | 0.39*** | −0.18*** | −0.21*** | −0.13*** | 0.08*** | 0.19*** | 1.00 |

| RET (12) | −0.06*** | −0.17*** | −0.01 | 0.17*** | 0.08*** | −0.11*** | −0.09*** | 0.29*** | −0.08*** | 0.20*** | −0.01* |

- Panel A shows descriptive statistics and Panel B shows the correlation matrix of the variables. CGINDEX is the firm's governance index, INVDUR is the duration of institutional investment, CONCENTRATION is the Herfindahl index of institutional ownership, IO is the total institutional ownership in each firm, FSIZE is the logarithm of the firm's total assets, R&D is the ratio of research and development expenditure to total assets, VOLATILITY is the standard deviation of operating profit in the past 5 years, MTB is the ratio of the summation of market value of equity and long-term debt to total assets, LEVERAGE is the ratio of long-term debt to total assets, FCF is the ratio of the difference between operating cash flow and capital expenditure to total assets, FIRMAGE is the number of years since the firm first appears in the CRSP, and RET is the buy-and-hold stock returns over the past 5 years. The total number of observations is 19 204. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

3 Empirical Results

3.1 Regression Results Using the Level Variables

(1)

(1)We use lagged values of independent variables to mitigate a potential reverse causality problem.

We estimate regression model (1) using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method with standard errors clustered by firm and year in order to address the possible biases in the standard errors in the presence of cross-sectional and time-series dependence (Petersen, 2009). The first column in Table 3 shows the results when we include institutional ownership concentration (CONCENTRATION) and the second column shows the results when we include institutional ownership (IO) in the regression.14 The estimated coefficients on INVDUR are positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that companies that are held by institutions with a longer investment horizon exhibit a higher CGINDEX. The coefficient on CONCENTRATION (IO) is also positive and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that institutional investors exercise a greater influence on corporate governance when their ownership is concentrated (large). We interpret these results as evidence that institutional investors’ monitoring incentives and abilities increase with both their investment duration and ownership concentration (size).

| Dependent variable: CGINDEXit | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Intercept | 17.723*** | 18.054*** |

| (31.02) | (32.92) | |

| INVDURit−1 | 0.496*** | 0.659*** |

| (7.95) | (10.60) | |

| CONCENTRATIONit−1 | 0.243*** | |

| (11.60) | ||

| IOit−1 | 4.286*** | |

| (25.79) | ||

| FSIZEit−1 | 0.664*** | 0.298*** |

| (28.44) | (10.09) | |

| R&Dit−1 | 1.830*** | 1.094** |

| (4.17) | (2.53) | |

| VOLATILITYit−1 | 2.023*** | 2.501*** |

| (5.44) | (6.74) | |

| MTBit−1 | −0.146*** | −0.184*** |

| (−5.99) | (−7.75) | |

| LEVERAGEit−1 | −2.052*** | −1.523*** |

| (−11.81) | (−8.83) | |

| FCFit−1 | −0.041 | −0.443* |

| (−0.18) | (−1.91) | |

| FIRMAGEit−1 | 0.034*** | 0.045*** |

| (12.06) | (15.80) | |

| RETit−1 | −0.106*** | −0.139*** |

| (−6.45) | (−8.55) | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.126 | 0.148 |

| Number of observations | 19 204 | 19 204 |

- CGINDEXit is firm i's governance index in year t, INVDURit−1 is the institutional investment duration of stock i in year t−1, CONCENTRATIONit−1 is the Herfindahl index of firm i in year t−1, IOit−1 is aggregate institutional ownership of firm i in year t−1, FSIZEit−1 is the logarithm of firm i's total assets in year t−1, R&Dit−1 is the ratio of firm i's research and development expenditure to total assets in year t−1, VOLATILITYit−1 is the standard deviation of firm i's operating profit in the past 5 years preceding year t−1, MTBit−1 is the ratio of the summation of firm i's market value of equity and long-term debt to total assets in year t−1, LEVERAGEit−1 is the ratio of firm i's long-term debt to total assets in year t−1, FCFit−1 is the ratio of the difference between firm i's operating cash flow and capital expenditure to total assets in year t−1, RETit−1 is the buy-and-hold stock returns over the past 5 years, and FIRMAGEit−1 is one minus the number of years since firm i first appears in the CRSP. We estimate the coefficients using the pooled OLS regression with standard errors clustered by firm and year. The figures in parentheses are t-statistics. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

The results for the other control variables are generally in line with those reported in previous studies. For example, we find that CGINDEX is positively related to firm size, R&D expenditures, operating profit volatility, and firm age, and negatively related to market-to-book ratio, leverage, free cash flow, and past stock returns.

3.2 Regression Results Using Changes in the Variables

Regression models using changes in the variables are less likely to suffer from econometric problems (e.g. nonstationarity) than those using the level variables. As a robustness check, we examine whether changes in CGINDEX can be explained by changes in INVDUR. To account for the possibility that changes in CGINDEX and INVDUR may occur gradually and test the hypothesized direction of causality, we regress changes in CGINDEX between year t and year t−2 on changes in INVDUR and control variables between year t−1 and year t−3. The results (see Panel A in Table 4) show that the coefficients on changes in INVDUR are positive and significant, providing further evidence that long-term institutional investors play a greater role in corporate governance than do short-term institutional investors. The regression coefficients on changes in CONCENTRATION and IO are both positive, but only the coefficient on IO is statistically significant.

| Panel A: Regression on changes in investment duration | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: ∆CGINDEXit | ||

| (1) | (2) | |

| Intercept | 0.927 | 0.828 |

| (1.57) | (1.41) | |

| ∆INVDURit−1 | 0.469*** | 0.555*** |

| (6.75) | (7.99) | |

| ∆CONCENTRATIONit−1 | 0.047 | |

| (1.38) | ||

| ∆IOit−1 | 2.820*** | |

| (8.21) | ||

| ∆FSIZEit−1 | −0.037 | −0.324*** |

| (−0.34) | (−2.83) | |

| ∆R&Dit−1 | 1.615** | 1.516** |

| (2.13) | (2.00) | |

| ∆VOLATILITYit−1 | 4.016*** | 4.098*** |

| (8.23) | (8.41) | |

| ∆MTBit−1 | −0.432*** | −0.467*** |

| (−16.84) | (−17.89) | |

| ∆LEVERAGEit−1 | −0.901*** | −0.662** |

| (−3.23) | (−2.37) | |

| ∆FCFit−1 | −0.100 | −0.097 |

| (−0.34) | (−0.34) | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.031 | 0.035 |

| Number of observations | 14 098 | 14 098 |

| Panel B: Regression on changes in the ownership or changes in the number of long-term institutions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: ∆CGINDEXit | ||

| (1) | (2) | |

| Intercept | 0.818 | 0.891 |

| (1.28) | (1.39) | |

| ∆IO_LONGit−1 | 4.507*** | |

| (10.50) | ||

| ∆IO_SHORTit−1 | 0.467 | |

| (1.07) | ||

| ∆NOINST_LONGit−1 | 0.583*** | |

| (6.33) | ||

| ∆NOINST_SHORTit−1 | −0.034 | |

| (−0.53) | ||

| ∆CONCENTRATIONit−1 | 0.040 | |

| (1.12) | ||

| ∆NOINSTit−1 | 0.316** | |

| (2.50) | ||

| ∆FSIZEit−1 | −0.457*** | −0.247* |

| (−3.37) | (−1.84) | |

| ∆R&Dit−1 | 1.527* | 1.764** |

| (1.89) | (2.19) | |

| ∆VOLATILITYit−1 | 4.480*** | 4.464*** |

| (7.89) | (7.84) | |

| ∆MTBit−1 | −0.540*** | −0.499*** |

| (−18.55) | (−17.22) | |

| ∆LEVERAGEit−1 | −0.827*** | −1.018*** |

| (−2.69) | (−3.30) | |

| ∆FCFit−1 | −0.240 | −0.224 |

| (−0.77) | (−0.71) | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.042 | 0.035 |

| Number of observations | 13 133 | 13 133 |

- In Panel A, we regress changes in CGINDEX between year t and t−2 on changes in INVDUR and control variables between year t−1 and t−3. In Panel B, we classify an institution as a long-term (short-term) institution if its length of investment in a firm is longer (shorter) than 2 years and calculate the total ownership of long-term institutions (IO_LONG) and the total ownership of short-term institutions (IO_SHORT) for each firm. Similarly, we count the number of long-term institutions (NOINST_LONG) and the number of short-term institutions (NOINST_SHORT) for each firm. We regress changes in CGINDEX between year t and t−2 on changes in these and other control variables between year t−1 and t−3. We estimate the coefficients using the pooled OLS regression with standard errors clustered by firm and year. The figures in parentheses are t-statistics. See Appendix 2 for the definition of each variable. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

To further assess the robustness of the relation between institutional investment duration and CGINDEX, we classify an institution as a long-term (short-term) institution if its length of investment in a firm is longer (shorter) than 2 years and calculate the total ownership of long-term institutions (IO_LONG) and the total ownership of short-term institutions (IO_SHORT) for each firm. Similarly, we count the number of long-term institutions (NOINST_LONG) and the number of short-term institutions (NOINST_SHORT) for each firm. The first column in Panel B of Table 4 shows the results when we include changes in the total ownership of long-term institutions (∆IO_LONG) and changes in the total ownership of short-term institutions (∆IO_SHORT) in the regression.15 Similarly, the second column shows the results when we include changes in the number of long-term institutions (∆NOINST_LONG) and changes in the number of short-term institutions (∆NOINST_SHORT) in the regression. As in Panel A, we regress changes in CGINDEX between year t and year t−2 on changes in independent variables between year t−1 and year t−3.

We find that the coefficient on ∆IO_LONG (∆NOINST_LONG) is positive and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that an increase in the ownership (number) of long-term institutions in a firm is associated with an improvement in the firm's governance structure. In contrast, we find that the coefficient on ∆IO_SHORT is not significantly different from zero and the coefficient ∆NOINST_SHORT is significantly negative. These results suggest that only long-term institutions exert a positive impact on CGINDEX.

3.3 Regression Results by Governance Categories

In the previous sections, we established a positive relation between the broadly defined index of corporate governance and the investment duration of institutional investors. In this section we shed further light on the effect of institutional investment on corporate governance by examining which specific governance categories are related to institutional investment duration. Shareholder activism is a costly endeavor with uncertain outcomes for institutional investors. Consequently, institutional investors may put more effort into select governance features that they consider most important for improving firm performance.

To determine which governance categories are related to institutional investment duration, we regress CGINDEX for each one of the six governance categories in the ISS database on the same set of explanatory and control variables that are included in regression model (1).16 The results (see Table 5) show that the coefficients on INVDUR are positive and significant in the regression model for each of the following governance categories: audit, board, compensation, progressive practices, regardless of whether we include either CONCENTRATION or IO in the model. These results indicate that the presence of institutional investors with a long-term investment horizon increases the likelihood of a firm's adoption of the best governance standards in these categories. In contrast, the presence of long-term institutional investors does not have an impact on the governance practices related to either anti-takeover or executive and director ownership structure.

| Dependent variable: CGINDEXit | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance categories | ||||||||||||

| AUDIT | BOARD | CHARTER/BYLAWS | COMPENSATION | OWNERSHIP | PROGRESSIVE PRACTICES | |||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

| Intercept | 2.364*** | 2.374*** | 6.067*** | 6.249*** | 4.256*** | 4.213*** | 4.711*** | 4.706*** | 0.634*** | 0.688*** | −0.356* | −0.223 |

| (26.74) | (26.81) | (22.75) | (24.42) | (25.28) | (25.66) | (29.80) | (29.69) | (7.60) | (8.77) | (−1.77) | (−1.20) | |

| INVDURit−1 | 0.095*** | 0.099*** | 0.171*** | 0.261*** | −0.031 | −0.048** | 0.073*** | 0.072*** | 0.017 | 0.043*** | 0.168*** | 0.231*** |

| (8.51) | (8.86) | (5.70) | (8.71) | (−1.58) | (−2.45) | (4.52) | (4.47) | (1.56) | (4.04) | (7.93) | (10.93) | |

| CONCENTRATIONit−1 | 0.002 | 0.133*** | −0.017*** | 0.001 | 0.037*** | 0.088*** | ||||||

| (0.69) | (13.79) | (−2.77) | (0.20) | (9.97) | (11.77) | |||||||

| IOit−1 | 0.135*** | 2.348*** | −0.566*** | −0.065 | 0.708*** | 1.736*** | ||||||

| (4.71) | (31.08) | (−11.53) | (−1.53) | (23.03) | (30.16) | |||||||

| FSIZEit−1 | −0.050*** | −0.062*** | 0.316*** | 0.115*** | −0.099*** | −0.047*** | 0.006 | 0.012* | 0.133*** | 0.071*** | 0.364*** | 0.214*** |

| (−12.35) | (−12.49) | (29.09) | (8.66) | (−13.66) | (−5.51) | (0.95) | (1.68) | (30.94) | (13.45) | (45.93) | (21.61) | |

| R&Dit−1 | −0.064 | −0.089 | 1.525*** | 1.121*** | −0.593*** | −0.049*** | −0.351*** | −0.338*** | 0.467*** | 0.344*** | 0.730*** | 0.427*** |

| (−0.82) | (−1.14) | (6.92) | (5.20) | (−4.17) | (−3.44) | (−2.89) | (−2.78) | (6.09) | (4.52) | (4.80) | (2.86) | |

| VOLATILITYit−1 | 0.203*** | 0.222*** | 0.739*** | 1.001*** | 0.296** | 0.223* | 0.184* | 0.174* | 0.214*** | 0.295*** | 0.379*** | 0.579*** |

| (3.10) | (3.37) | (4.06) | (5.57) | (2.57) | (1.95) | (1.81) | (1.71) | (3.76) | (5.23) | (2.92) | (4.48) | |

| MTBit−1 | −0.048*** | −0.049*** | −0.057*** | −0.078*** | −0.008 | −0.004 | −0.011* | −0.010* | 0.012*** | 0.006* | −0.034*** | −0.049*** |

| (−12.02) | (−12.28) | (−5.00) | (−7.03) | (−1.21) | (−0.59) | (−1.90) | (−1.84) | (3.17) | (1.62) | (−4.19) | (−6.27) | |

| LEVERAGEit−1 | −0.145*** | −0.128*** | −0.980*** | −0.690*** | −0.081 | −0.153*** | 0.180*** | 0.171*** | −0.217*** | −0.129*** | −0.776*** | −0.560*** |

| (−4.88) | (−4.27) | (−11.86) | (−8.47) | (−1.60) | (−2.99) | (4.20) | (3.97) | (−7.24) | (−4.32) | (−12.84) | (−9.41) | |

| FCFit−1 | −0.025 | −0.038 | −0.132 | −0.352*** | −0.018 | 0.038 | 0.110* | 0.117* | 0.072* | 0.005 | −0.086 | −0.250*** |

| (−0.60) | (−0.93) | (−1.15) | (−3.14) | (−0.25) | (0.52) | (1.77) | (1.88) | (1.77) | (0.12) | (−1.05) | (−3.12) | |

| FIRMAGEit−1 | 0.001* | 0.001*** | 0.017*** | 0.023*** | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.002** | 0.001** | 0.005*** | 0.001*** | 0.009*** | 0.014*** |

| (1.92) | (2.86) | (14.06) | (18.91) | (1.02) | (−1.19) | (2.52) | (2.10) | (9.75) | (13.34) | (9.28) | (14.07) | |

| RETit−1 | −0.011*** | −0.012*** | −0.037*** | −0.054*** | 0.024*** | 0.028*** | −0.048*** | −0.048*** | −0.001 | −0.006** | −0.033*** | −0.046*** |

| (−4.02) | (−4.38) | (−4.84) | (−7.34) | (5.32) | (6.22) | (−13.40) | (−13.24) | (−0.40) | (−2.30) | (−5.99) | (−8.41) | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.130 | 0.161 | 0.040 | 0.046 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.144 | 0.144 | 0.195 | 0.225 |

| Number of observations | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 |

- To determine which governance categories are related to institutional investment duration, we regress CGINDEX for each one of the six governance categories in the ISS database on the same set of explanatory and control variables that are included in regression model (1). We estimate the coefficients using the pooled OLS regression with standard errors clustered by firm and year. The figures in parentheses are t-statistics. See Appendix 2 for the definition of each variable. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

The coefficients on CONCENTRATION and IO are generally consistent with prior empirical findings. Gillan et al. (2006) find that companies with higher institutional ownership have more powerful boards and more anti-takeover provisions. Similarly, we find that the coefficients on CONCENTRATION and IO are positive in the regression model for BOARD and negative in the regression model for CHATERS/BYLAWS.17 Johnson and Shackell (1997) show that a company is less likely to receive shareholder proposals on executive compensation when institutions hold a larger fraction of its shares. In contrast, we find that executive and director compensation is insignificantly related to CONCENTRATION and IO, but significantly related to INVDUR, suggesting that long-term institutional investors are more interested in executive and director compensation scheme than are short-term institutional investors.

4 Corporate Governance and Investment Duration by the Type of Institutions

In this section we examine whether the relation between corporate governance and institutional investment duration varies across the seven types of institutions: public pension funds, private pension funds, hedge funds, bank trusts, insurance companies, investment companies, and investment advisors. Both anecdotal evidence and academic research indicate that pension funds are amongst the most active investors in the United States. Gillan and Starks (2000) show that institutional investors submitted 463 proxy proposals between 1987 and 1994 and the majority of these proposals were sponsored by pension funds. Although the proxy proposals submitted by pension funds have declined significantly since the early 1990s, pension funds have been most vocal in calling for corporate governance reforms through direct negotiation with corporate management and/or public targeting. Brav et al. (2008) investigate hedge funds’ activism (through Schedule 13D filing) and find increases in target firms’ dividend payout, operating performance, and CEO turnover. Almazan et al. (2005) categorize bank trusts and insurance companies as passive investors and independent investment advisors and investment companies as active investors and find that only investment advisors and investment companies exert influences on executive compensation.

To examine whether the effect of institutional investment duration on corporate governance varies with the type of institutions, we conduct regression analysis for each type of institution and report the results in Table 6. The first three columns show the results when we include the investment duration (INVDUR_TYPE) of public pension funds, private pension funds, or hedge funds as an explanatory variable in the regression model. (Appendix 3 shows the list of public and private pension funds.) The next four columns show the results when we include the investment duration of bank trusts, insurance companies, investment companies, or investment advisors as an explanatory variable. In each of these regressions, we also include the investment duration of all other types of institutional investors (INVDUR_OTHER TYPE). Hence, for example, we include both the investment duration of public pension funds and the investment duration of all other institutional investors in the regression model for public pension funds. Similarly, we include both the ownership of each type of institutional investors (IO_TYPE) and the total ownership of all other institutional investors (IO_OTHER TYPE) in the regression model for each type of institutional investors to assess the effect of ownership level on corporate governance.

| Dependent variable: CGINDEXit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of institution | |||||||

| Public pension fund | Private pension fund | Hedge fund | Bank | Insurance | Investment company | Investment advisory | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Intercept | 17.719*** | 14.189*** | 17.044*** | 18.116*** | 15.987*** | 17.718*** | 18.320*** |

| (28.71) | (16.71) | (27.15) | (32.55) | (23.94) | (31.25) | (32.75) | |

| INVDUR_TYPEit−1 | 2.015*** | 0.968 | 0.726*** | 1.71*** | 1.783*** | 0.857*** | 1.190*** |

| (3.69) | (0.37) | (5.71) | (9.27) | (4.67) | (9.90) | (12.40) | |

| IO_TYPEit−1 | −12.198*** | −52.395** | 11.133*** | 3.399*** | −12.445*** | 0.864 | −0.094 |

| (−2.89) | (−2.50) | (16.73) | (4.19) | (−4.81) | (1.05) | (−0.21) | |

| INVDUR_OTHER TYPEit−1 | 0.932*** | 1.786*** | 1.010*** | 0.631*** | 1.192*** | 0.899*** | 0.417*** |

| (12.24) | (14.54) | (12.47) | (9.40) | (13.75) | (11.29) | (5.86) | |

| IO_OTHER TYPEit−1 | 4.758*** | 6.234*** | 2.486*** | 4.688*** | 5.622*** | 4.967*** | 7.824*** |

| (21.55) | (20.48) | (9.52) | (17.34) | (25.85) | (21.54) | (21.88) | |

| FSIZEit−1 | 0.278*** | 0.452*** | 0.357*** | 0.269*** | 0.394*** | 0.312*** | 0.262*** |

| (8.58) | (10.14) | (11.00) | (8.75) | (11.57) | (9.84) | (8.55) | |

| R&Dit−1 | 1.037** | 1.248* | 0.604 | 1.159*** | 0.956* | 1.026** | 0.975** |

| (2.05) | (1.71) | (1.27) | (2.59) | (1.68) | (2.24) | (2.19) | |

| VOLATILITYit−1 | 2.855*** | 3.838*** | 2.740*** | 2.584*** | 3.318*** | 2.580*** | 2.574*** |

| (6.38) | (5.71) | (6.70) | (6.58) | (6.58) | (6.27) | (6.64) | |

| MTBit−1 | −0.202*** | −0.232*** | −0.171*** | −0.197*** | −0.203*** | −0.185*** | −0.181*** |

| (−7.66) | (−7.10) | (−6.84) | (−8.11) | (−7.38) | (−7.42) | (−7.58) | |

| LEVERAGEit−1 | −1.602*** | −1.996*** | −1.724*** | −1.504*** | −1.623*** | −1.615*** | −1.499*** |

| (−8.04) | (−7.93) | (−9.11) | (−8.40) | (−7.68) | (−8.80) | (−8.42) | |

| FCFit−1 | −0.573** | −0.940** | −0.698*** | −0.493** | −0.743** | −0.614** | −0.493** |

| (−2.09) | (−2.45) | (−2.74) | (−2.04) | (−2.46) | (−2.47) | (−2.06) | |

| FIRMAGEit−1 | 0.042*** | 0.034*** | 0.044*** | 0.045*** | 0.040*** | 0.042*** | 0.045*** |

| (13.83) | (9.86) | (14.67) | (15.50) | (12.79) | (14.19) | (15.64) | |

| RETit−1 | −0.128*** | −0.119*** | −0.128*** | −0.135*** | −0.128*** | −0.140*** | −0.130*** |

| (−7.57) | (−5.82) | (−7.69) | (−8.20) | (−7.16) | (−8.38) | (−7.96) | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.136 | 0.167 | 0.150 | 0.147 | 0.159 | 0.150 | 0.151 |

| Number of observations | 16 545 | 12 935 | 17 595 | 18 687 | 15 730 | 18 271 | 18 626 |

- To examine whether the effect of institutional investment duration on corporate governance varies with the type of institutions, we conduct regression analysis for each type of institutions. The first three columns show the results when we include the investment duration (INVDUR_TYPE) of public pension funds, private pension funds, or hedge funds as an explanatory variable in the regression model. (Appendix 3 shows the list of public and private pension funds.) The next four columns show the results when we include the investment duration of bank trusts, insurance companies, investment companies, or investment advisors as an explanatory variable. In each of these regressions, we also include the investment duration of all other types of institutional investors (INVDUR_OTHER TYPE). Hence, for example, we include both the investment duration of public pension funds and the investment duration of all other institutional investors in the regression model for public pension funds. Similarly, we include both the ownership of each type of institutional investors (IO_TYPE) and the total ownership of all other institutional investors (IO_OTHER TYPE) in the regression model for each type of institutional investors to assess the effect of ownership level on corporate governance. We estimate the model using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method with standard errors clustered by firm and year. The figures in parentheses are t-statistics. See Appendix 2 for the definition of each variable. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

The results show that the coefficients on the investment duration of public pension funds, hedge funds, bank trusts, insurance companies, investment companies, and investment advisors are all positive and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient on the investment duration of private pension fund is positive but insignificant. These results suggest that institutions with a longer investment horizon exert greater influences on corporate governance regardless of their type (except private pension funds).

Comparison of the regression coefficients on investment duration across different types of institutions indicates that the relation between CGINDEX and INVDUR is strongest for public pension funds, followed by insurance companies, banks, and investment advisors. These results suggest that how investment duration affects corporate governance varies across different types of institutions, reflecting their differential incentives and abilities to influence corporate governance. In particular, the large and highly significant coefficients on investment duration for public pension funds are consistent with both anecdotal evidence and the finding of prior research that public pension funds are amongst the most active investors in the United States. Not surprisingly, the coefficients on INVDUR_OTHER TYPE are all positive and significant and tend to be smaller when the coefficients on INVDUR_TYPE are larger across different types of institutional investors.

The effect of institutional ownership (IO) on the governance index varies significantly across different types of institutions. For example, the coefficients on IO_TYPE are negative and significant for pension funds and insurance companies, but positive and significant for hedge funds and banks, indicating that greater ownership by pension funds and insurance companies does not necessarily imply better corporate governance. Finally, the coefficients on IO_OTHER TYPE are all positive and significant across all types of institutions. This result indicates that although the effect of ownership size on CGINDEX varies significantly across different types of institutions, they exert in aggregate a positive impact on CGINDEX.

5 Effect of Liquidity on the Relation Between Investment Duration and Corporate Governance

Institutional investors’ incentives to engage in shareholder activism are likely to depend on the benefit and cost associated with the activism. We conjecture that the benefit and cost associated with shareholder activism vary with the stock market liquidity of the firm's shares. If the liquidity of the firm's shares is high, institutional investors can easily exit (i.e. sell the firm's shares) when they are not satisfied with the firm's management. Hence, higher liquidity may imply lower shareholder activism by institutional investors (Bhide, 1993), which may adversely affect corporate governance. Conversely, higher liquidity may be associated with better governance structures if the threat of exit is more effective for firms with higher stock market liquidity of their shares. Managers of such firms may make greater endeavor to improve governance structure in an effort to prevent institutional investors from exit, which may adversely affect share price. These considerations suggest that the effect of liquidity on corporate governance is likely an empirical question.

We measure the liquidity of the firm's shares by the proportional bid-ask spread using data from the CRSP database.18 Prior research (e.g. Bessembinder, 2003) uses the bid-ask spread to perform inter-market comparisons of trading costs. In addition, regulators enact various market reforms to reduce the cost of trading and assess the effectiveness of these reforms by analyzing their impact on the bid-ask spread.19 We calculate the bid-ask spread of stock i on day τ using the following formula: SPREADiτ = (Askiτ − Bidiτ)/Miτ; where Askiτ is the ask price of stock i on day τ, Bidiτ is the bid price of stock i on day τ, and Miτ is the mean of Askiτ and Bidiτ. For each stock, we then calculate the average spread during each year from 2000 through 2008. We include both the spread and the interaction variable between the spread and institutional investment duration in the regression model.

The results (see Table 7) show that the coefficients on the interaction variable are negative and significant, regardless of whether we include either COCENTRATION or IO in the model, indicating that the positive effect of investment duration on CGINDEX decreases with the spread.20 Put differently, longer institutional investor duration is more effective in improving a firm's governance structure when the stock market liquidity of the firm is higher. These results are consistent with the notion that when institutional investors can exit more easily, firms are more inclined to improve governance structure to avoid their exit. Table 7 also shows that the coefficients on the spread are negative and significant, which is consistent with the finding of prior research (see Chung et al., 2010).

| Dependent variable: CGINDEXit | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Intercept | 20.896*** | 20.557*** |

| (30.82) | (30.90) | |

| INVDURit−1 | 1.679*** | 1.797*** |

| (16.74) | (17.96) | |

| SPREADit−1 | −1.078*** | −0.855*** |

| (−6.98) | (−5.55) | |

| INVDUR × SPREADit−1 | −0.482*** | −0.523*** |

| (−7.98) | (−8.73) | |

| CONCENTRATIONit−1 | 0.091*** | |

| (4.33) | ||

| IOit−1 | 1.812*** | |

| (10.12) | ||

| FSIZEit−1 | −0.008 | −0.123*** |

| (−0.27) | (−3.73) | |

| R&Dit−1 | −0.427 | −0.689 |

| (−0.75) | (−1.21) | |

| VOLATILITYit−1 | 2.399*** | 2.638*** |

| (4.96) | (5.47) | |

| MTBit−1 | −0.344*** | −0.348*** |

| (−13.35) | (−13.60) | |

| LEVERAGEit−1 | −0.094 | 0.001 |

| (−0.48) | (0.00) | |

| FCFit−1 | 0.308 | 0.085 |

| (1.05) | (0.29) | |

| FIRMAGEit−1 | 0.036*** | 0.040*** |

| (13.02) | (14.35) | |

| RETit−1 | −0.151*** | −0.155*** |

| (−9.45) | (−9.75) | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.263 | 0.267 |

| Number of observations | 16 668 | 16 668 |

- We calculate the bid-ask spread of stock i on day τ using the following formula: SPREADiτ = (Askiτ − Bidiτ)/Miτ; where Askiτ is the ask price of stock i on day τ, Bidiτ is the bid price of stock i on day τ, and Miτ is the mean of Askiτ and Bidiτ. For each stock, we then calculate the average spread during each year from 2000 through 2008. We include both the spread and the interaction variable between the spread and institutional investment duration in the regression model. We estimate the model using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method with standard errors clustered by firm and year. The figures in parentheses are t-statistics. See Appendix 2 for the definition of each variable. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

6 Robustness Check Using Alternative Measures of Institutional Investment Duration

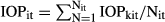

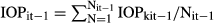

In this section we use alternative measures of institutional investment duration to assess the robustness of our results. Elyasiani and Jia (2008) employ the persistency of institutional ownership, the non-zero-points duration, and the maintain-stake-points duration to investigate the monitoring effect of long-term institutional investors on firm performance. Following their study, we first calculate the mean and standard deviation of institution k's ownership in firm i over the past 20 quarters. We use the ratio of the mean of the ownership to the standard deviation over the past 20 quarters as institution k's ownership persistency in firm i at time t (IOPkit). We then measure firm i's institutional ownership persistency at time t by  , where Nit is the number of institutions that own firm i's shares at time t.

, where Nit is the number of institutions that own firm i's shares at time t.

The non-zero-points duration is the number of quarters during which institution k holds non-zero shares over the past 20 quarters. The maintain-stake-points duration is the number of quarters during which institution k increases or maintains the ownership stake over the past 20 quarters. For the firm-level duration, both duration measures are averaged across all institutions in the firm's ownership structure.

Table 8 shows the regression results using these alternative institutional duration measures. The first two columns show the results when we measure institutional investment duration with IOP, the next two columns show the results with the non-zero-points duration, and the last two columns show the results with the maintain-stake-points duration. The results show that the coefficients on these institutional duration measures are positive in all six regressions and statistically significant in most regressions (five out of six cases). These results suggest that CGINDEX increases with the stable and long-term existence of institutional investors, which is consistent with our main results presented above.

| Dependent variable: CGINDEXit Measures of investment duration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOP | NON-ZERO-POINTS | MAINTAIN-STAKE | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Intercept | 17.763*** | 18.183*** | 17.889*** | 17.889*** | 18.491*** | 19.010*** |

| (31.33) | (33.43) | (31.01) | (31.13) | (32.51) | (34.65) | |

| INVDUR it−1 | 1.032*** | 1.310*** | 0.176*** | 0.190*** | 0.028 | 0.053** |

| (10.52) | (13.31) | (11.94) | (13.11) | (1.33) | (2.50) | |

| CONCENTRATION it−1 | 0.255*** | 0.237*** | 0.255*** | |||

| (12.22) | (11.35) | (12.13) | ||||

| IOit−1 | 4.415*** | 4.192*** | 4.200*** | |||

| (26.64) | (25.31) | (25.25) | ||||

| FSIZE it−1 | 0.739*** | 0.387*** | 0.653*** | 0.306*** | 0.708*** | 0.366*** |

| (32.54) | (13.56) | (28.17) | (10.50) | (30.93) | (12.60) | |

| R&Dit−1 | 1.996*** | 1.300*** | 1.649*** | 0.945** | 1.951*** | 1.279*** |

| (4.54) | (2.99) | (3.78) | (2.20) | (4.44) | (2.95) | |

| VOLATILITY it−1 | 2.166*** | 2.657*** | 2.219*** | 2.598*** | 1.656*** | 2.023*** |

| (5.80) | (7.12) | (6.01) | (7.05) | (4.47) | (5.48) | |

| MTB it−1 | −0.146*** | −0.186*** | −0.129*** | −0.166*** | −0.148*** | −0.186*** |

| (−6.00) | (−7.86) | (−5.31) | (−7.00) | (−6.04) | (−7.78) | |

| LEVERAGE it−1 | −2.044*** | −1.504*** | −2.082*** | −1.586*** | −2.127*** | −1.634*** |

| (−11.75) | (−8.71) | (−12.00) | (−9.21) | (−12.21) | (−9.45) | |

| FCF it−1 | −0.189 | −0.644*** | 0.034 | −0.365 | −0.101 | −0.515** |

| (0.42) | (−2.76) | (0.14) | (−1.58) | (−0.43) | (−2.22) | |

| FIRMAGE it−1 | 0.032*** | 0.043*** | 0.031*** | 0.043*** | 0.039*** | 0.051*** |

| (11.14) | (14.86) | (11.01) | (14.98) | (13.92) | (17.73) | |

| RET it−1 | −0.113*** | −0.150*** | −0.074*** | −0.108*** | −0.124*** | −0.158*** |

| (−6.97) | (−9.39) | (−4.43) | (−6.60) | (−7.38) | (−9.57) | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.128 | 0.151 | 0.129 | 0.150 | 0.123 | 0.144 |

| Number of observations | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 | 19 204 |

-

In this table we use the following three alternative measures of institutional investment duration to assess the robustness of our results: the persistency of institutional ownership, the non-zero-points duration, and the maintain-stake-points duration. We first calculate the mean and standard deviation of institution k's ownership in firm i over the past 20 quarters. We use the ratio of the mean of the ownership to the standard deviation over the past 20 quarters as institution k's ownership persistency in firm i at time t−1 (IOPkit−1). We then measure firm i's institutional ownership persistency at time t−1 by

, where Nit−1 is the number of institutions which own firm i's shares at time t−1. The non-zero-points duration is the number of quarters during which institution k holds non-zero shares. The maintain-stake-points duration is the number of quarters during which institution k increases or maintains the ownership stake over the past 20 quarters. For the firm-level duration, both duration measures are averaged across all institutions in the firm's ownership structure. We estimate the model using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method with standard errors clustered by firm and year. The figures in parentheses are t-statistics. See Appendix 2 for the definition of each variable. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

, where Nit−1 is the number of institutions which own firm i's shares at time t−1. The non-zero-points duration is the number of quarters during which institution k holds non-zero shares. The maintain-stake-points duration is the number of quarters during which institution k increases or maintains the ownership stake over the past 20 quarters. For the firm-level duration, both duration measures are averaged across all institutions in the firm's ownership structure. We estimate the model using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method with standard errors clustered by firm and year. The figures in parentheses are t-statistics. See Appendix 2 for the definition of each variable. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

7 Summary and Concluding Remarks

Corporate ownership structure in the United States has gone through a major transformation during the last half-century. In particular, corporate ownership has become much more concentrated in the hands of institutional investors. Consequently, while corporate managers once faced a dispersed and relatively powerless crowd of shareholders, they now have to deal with an increasingly powerful group of institutional investors. Moreover, institutional investors have expanded the domain of their activism from standard shareholder rights to issues of how chief executive officers are chosen, how much executives are paid, and how the board is made up and structured.

Not surprisingly, researchers have paid increasing attention to institutional investors’ roles in the financial market, such as the effects of institutional ownership on firm value, analyst following, stock returns, and corporate governance. In particular, a large number of studies have examined whether and how institutional investors proactively work in partnership with companies to improve corporate governance structure. Some prior research focuses on shareholder activism by a particular institutional investor (such as CalPERS or TIAA-CREF) and other studies analyze the relation between the total institutional ownership of a firm and a specific aspect of its governance structure. In our study, we shed further light on the role of institutional investors in corporate governance by analyzing the effect of institutional investment duration on the broadly constructed index of corporate governance as well as on specific governance provisions.

Our results suggest that institutional influence on a firm's governance practices depends on how long they have held the firm's shares. The results are consistent with our conjecture that institutional investors with a shorter investment horizon would be less interested in spending resources on corporate governance because they are less likely to be the recipients of the resultant benefits. The long-term presence of institutional investors increases the likelihood of a firm's adoption of governance standards that are related to audit, board structure, executive and director compensation, and progressive practices, suggesting that institutional investors’ interest covers a broad range of corporate governance practices.

We also show that the relation between investment duration and corporate governance varies materially across different types of institutions, reflecting their differential incentives and abilities to influence corporate governance, The effect of investment duration on corporate governance is particularly strong for public pension funds, which is consistent with the finding of prior research that pension funds are amongst the most active investors in the United States. We also find evidence that longer institutional investor duration is more effective in improving corporate governance structure for firms with higher stock market liquidity.

Notes

Appendix 1

50 governance provisions used in the construction of the corporate governance index

| Provision | Governance standard |

|---|---|

| Audit | |

| Audit committee composition | Audit committee of the board should be composed solely of independent directors |

| Audit fees | Consulting fees (audit-related and other) should be less than audit fees |

| Audit ratification | Shareholders should be permitted to ratify management's selection of auditors each year |

| Audit rotation | The company should disclose its policy with respect to the rotation of auditors |

| Board | |

| Board composition | At least a majority of the directors on the board should be independent |

| Nominating committee composition | Nominating committee of the board should be composed solely of independent directors |

| Compensation committee composition | Compensation committee of the board should be composed solely of independent directors |

| Governance committee composition | The functions of a governance committee should be handled by a committee of the board, typically the nominating or the governance committee |

| Board structure | Directors should be accountable to shareholders on an annual basis |

| Board size | Boards should not have fewer than six members or more than 15 members |

| Change in board size | Shareholders should have the right to vote on changes to expand or contract size of the board |

| Cumulative voting | Shareholders should have the right to cumulate their votes for directors |

| Board served on by the CEO | The CEO should not serve on more than two other boards of public companies |

| Board served on by other than the CEO | Outside directors should be limited to service on the boards of four or fewer public companies |

| Former CEOs | Former CEOs should not serve on the board of directors |

| Chairman/CEO separation | The position of chairman and CEO should be separated and the chairman should be an independent outsider |

| Board guidelines | Board guidelines should be published on the company web site on an annual basis |

| Shareholder proposals | Management should take action on all shareholder proposals supported by a majority vote within 12 months of the shareholders’ meeting |

| Board attendance | Directors should attend at least 75% of board meetings |

| Board vacancies | Shareholders should be given an opportunity to vote on all directors selected to fill vacancies |

| Related party transaction | CEOs should not be the subject of transactions that create conflicts of interest as disclosed in the proxy statement |

| Charter/bylaws | |

| Poison pill adoption | The company should not have a poison pill in place |

| Amendment to the charter/bylaws | A simple majority vote should be required to amend the charter/bylaws and to approve mergers or business combinations |

| Approval of mergers | A simple majority vote should be required to approve mergers or business combinations |

| Written consent | Shareholders should be permitted to act by written consent |

| Special meetings | Shareholders should be permitted to call special meetings |

| Capital structure | Declawed preferred stock is viewed favorably |

| Board amendments | Board should not be permitted to amend the bylaws without shareholder approval |

| Capital structure-dual class | Common stock entitled to one vote is viewed favorably |

| Executive and director compensation | |

| Cost of option plans | An option-pricing model is used to measure the cost of all new stock-based incentive plans |

| Approval of option repricing | Plan documents should be written to expressively prohibit repricing without prior shareholder approval |

| Approval of option plans | All stock-based incentive plans should be submitted to shareholders for approval |

| Director compensation | Directors should receive a portion of their compensation in the form of stock |

| Compensation committee interlocks | No interlocking directors should serve on the compensation committee |

| Option repricing | Options should not have been repriced without shareholder approvals during the past 3 years |

| Option burn rate | Burn rates are considered excessive where average annual option grants exceed 2% of outstanding shares over the past 3 years or exceed one standard deviation from the industry mean |

| Option expensing | Companies are moving toward option expensing |

| Pension plans | Non-employee directors do not participate in company's pension plans |

| Corporate loans | Company does not provide any loans to executives for exercising options |

| Executive and director ownership | |

| Director stock ownership | All directors with more than 1 year of service should own stock |

| Stock ownership guidelines-executives | Executives should be subject to stock ownership guidelines |

| Stock ownership guidelines-directors | Directors should be subject to stock ownership guidelines |

| Progressive practices | |

| Board performance reviews | A policy of conducting annual board performance reviews should be disclosed |

| Meeting of outside directors | A policy specifying that directors should meet without the CEO should be disclosed |

| CEO succession plan | A board-approved CEO succession plan should be in place and evaluated by the directors periodically |

| Outside advisors | A policy authorizing the board to hire its own advisors should be disclosed |

| Director resignation | A policy requiring directors to resign upon a change in job status should be disclosed |

| Retirement age | A retirement age or term limits serve as useful tools for ensuring that new board is regularly sought |

| State of incorporation | |

| Incorporation in a state with anti-takeover provisions | Incorporation in a state without any anti-takeover provisions, or opting out of such protections is viewed favorably |

Appendix 2

Variable definitions

| Variable name | Variable definition |

|---|---|

| CGINDEXit | Firm i's governance index in year t, which is defined as the number of governance provisions that satisfies the minimum standard provided in ISS Corporate Governance: Best Practices User Guide and Glossary (2008) |

| INVDURit−1 | The institutional investment duration of stock i in year t−1, which is defined as INVDURit−1 = ∑[wkit−1 × log(INVDURkit−1)], where wkit−1 is the fraction of firm i's total institutional ownership held by institution k at the end of year t−1 and ∑ denotes the summation over k. To determine the investment duration of institution k in stock i, we first identify the first quarter in which institution k reported its shareholding in firm i. We then measure institution k's investment duration for firm i at the end of year t−1, INVDURkit−1, by the number of quarters between the first quarter and the last quarter of year t−1 |

| CONCENTRATIONit−1 | Herfindahl index of firm i in year t−1, which is defined as Hit−1 = 100 ∑Skt−12, where Skt−1 is the fraction of firm i's shares held by institution k in year t−1 and ∑ denotes summation over k |

| IOit−1 | The total institutional ownership of firm i in year t−1 |

| FSIZEit−1 | The logarithm of firm i's total assets in year t−1 |

| R&Dit−1 | The ratio of firm i's research and development expenditure to total assets in year t−1 |

| VOLATILITYit−1 | The standard deviation of firm i's operating profit in the past 5 years preceding year t−1 |

| MTBit−1 | The ratio of the summation of firm i's market value of equity and long-term debt to total assets in year t−1 |

| LEVERAGEit−1 | The ratio of firm i's long-term debt to total assets in year t−1 |

| FCFit−1 | The ratio of the difference between firm i's operating cash flow and capital expenditure to total assets in year t−1 |

| RETit−1 | The buy-and-hold stock returns over the past 5 years |

| FIRMAGEit−1 | One minus the number of years since firm i first appears in the CRSP |

| IO_LONGit−1 | The total long-term institutional ownership of firm i in year t−1. We classify an institution as a long-term institution if its length of investment in a firm is longer than 2 years |

| IO_SHORTit−1 | The total short-term institutional ownership of firm i in year t−1. We classify an institution as a short-term institution if its length of investment in a firm is shorter than 2 years |

| NOINST_LONGit−1 | The number of long-term institutional investors for firm i in year t−1. We classify an institution as a long-term institution if its length of investment in a firm is longer than 2 years |

| NOINST_SHORTit−1 | The number of short-term institutional investors for firm i in year t−1. We classify an institution as a short-term institution if its length of investment in a firm is shorter than 2 years |

| SPREADit−1 | The bid-ask spread of firm i in year t−1. We calculate the bid-ask spread of stock i on day τ using the following formula: SPREADiτ = (Askiτ − Bidiτ)/Miτ; where Askiτ is the ask price of stock i on day τ, Bidiτ is the bid price of stock i on day τ, and Miτ is the mean of Askiτ and Bidiτ. For each stock, we then calculate the average spread during each year |

| IOPit−1 | The institutional ownership propensity of firm i in year t−1. We first calculate the mean and standard deviation of institution k's ownership in firm i over the past 20 quarters. We use the ratio of the mean of the ownership to the standard deviation over the past 20 quarters as institution k's ownership persistency in firm i at time t−1 (IOPkit−1). We then measure firm i's institutional ownership persistency at time t−1 by  , where Nit−1 is the number of institutions which own firm i's shares at time t−1 , where Nit−1 is the number of institutions which own firm i's shares at time t−1 |

| NON-ZERO-POINTSit−1 | The number of quarters during which institution k holds non-zero shares |

| MAINTAIN-STAKEit−1 | The number of quarters during which institution k increases or maintains the ownership stake over the past 20 quarters |

Appendix 3

The list of public and private pension funds with 13F filings

| Public pension funds | Private pension funds |

|---|---|

| California Legislators Retirement System | Allstate Agents Pension Funds |

| California Public Employees’ Retirement System | Allstate Retirement Plan |

| New York State Common Retirement Fund | Amica Pension funds |

| State Board of Administration of Florida | Atlantic Richfield Co. |

| Teacher Retirement System of Texas | Bethlehem Steel Pension |

| New York State Teachers’ Retirement System | Commonwealth Edison Pooled Fund |

| State of Wisconsin Investment Board | Digital Equipment Pension Trust |

| Ohio Public Employees Retirement System | DuPont Pension De Nemours & Co. |

| State Teachers’ Retirement System of Ohio | Financial Institutions Retirement Fund |

| Virginia Retirement System | General Electric Insurance Plan Trust |

| Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement | General Electric Pension Trust |

| Public Employees’ Retirement Association of Colorado | General Electric Medcare Trust |

| Maryland State Retirement & Pension System | Grumman Corporation Pension Fund |

| Alaska Retirement Management Board | IBM Retirement Plan |

| Kentucky Teachers’ Retirement System | Pichin Corp (TWA Retirement Plans) |

| School Employees of Retirement System of Ohio | Trans World Airlines Retirement |

| New Mexico Educational Retirement Board | US Steel and Carnegie Pension |

| Missouri State Employees’ Retirement System | YMCA Retirement Fund |

| Montana Board of Investments | General Motors Investment Management |

| Lockheed Martin Investment Management | |

| Verizon Investment Management | |

| Exxon Mobil Investment Management | |

| College Retirement Equities Fund |